Abstract

Strain hardening capability is critical for metallic materials to achieve high ductility during plastic deformation. A majority of nanocrystalline metals, however, have inherently low work hardening capability with few exceptions. Interpretations on work hardening mechanisms in nanocrystalline metals are still controversial due to the lack of in situ experimental evidence. Here we report, by using an in situ transmission electron microscope nanoindentation tool, the direct observation of dynamic work hardening event in nanocrystalline nickel. During strain hardening stage, abundant Lomer-Cottrell (L-C) locks formed both within nanograins and against twin boundaries. Two major mechanisms were identified during interactions between L-C locks and twin boundaries. Quantitative nanoindentation experiments recorded show an increase of yield strength from 1.64 to 2.29 GPa during multiple loading-unloading cycles. This study provides both the evidence to explain the roots of work hardening at small length scales and the insight for future design of ductile nanocrystalline metals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In polycrystalline metals with coarse grain size, strain hardening is typically described by Taylor relation, where the increases in flow stress is tied to increased dislocation densities1,2. During plastic deformation, dislocation networks (or forest dislocations) may form in grain interior and thus become barriers to the propagation of successive mobile dislocations. Additionally strain hardening can also be described in terms of the decreasing mean free path of a dislocation and the reduced number of active slip systems for dislocations adjacent to barriers, such as grain boundaries or twin boundaries3,4. Therefore control of slip distance by microstructural refinement can provide a feasible hardening mechanism.

Ultrafine grained and nanocrystalline (nc) materials have a large population of grain boundaries which are considered natural barriers to the propagation of dislocations. Indeed ultra-high mechanical strength has been achieved in nc and recently nanotwinned (nt) metals5,6,7,8,9,10,11. The size-dependent hardening has been explained by the Hall-Petch relationship, where the decrease of dislocation pile-ups in fine nc and nt metals leads to strengthening5,6,12. A recent study has suggested dislocation multi-junction formation in single crystal bcc molybdenum measurably increases the strength during a uniaxial compression testing13.

Although nc metals can have much greater mechanical strength than their bulk counterparts, their ductility is typically low (less than a few percent of true strain) with a handful of exceptions. Strain hardening, which is crucial to achieve high ductility, is typically diminished in nc metals, or very often absent in many cases. There are various mechanisms that explain the lack of strain hardening in nc metals. Grain boundaries are effective sources and sinks for dislocations. Dislocations once emitted from grain boundaries may be absorbed rapidly by opposite grain boundaries in nc metals. Thus there may be less sustainable dislocation networks within the grains to provide the necessary strain hardening. In situ X-ray experiments evidenced rapid dislocation recovery events during unloading of plastically deformed nc Ni14. On the other hand, L-C locks associated with stair-rod dislocations have been observed near grain and twin boundaries after rolling of nc Ni and were proposed to be effective barriers to mobile dislocations and result in work hardening15. There is no in situ evidence to explain the origin of such controversy. Additionally stacking fault energy (SFE) appears to play an important role on work hardening capability of nc metals. Stacking faults appear to inject work hardening capability in low SFE metals16.

Despite extensive studies on work hardening in metallic materials, most of the previous works focused on post-deformation microstructural analysis. Meanwhile, to directly probe the structure-property relationships, various real time phenomena have recently been recorded with in situ TEM mechanical testing of different materials systems. Among these studies, several are noteworthy, including evidence of mechanical annealing and dislocation source starvation in nickel pillar17, increment of dislocation nucleation rate at higher strain rate within single crystal Al18, dislocation slip in TiN thin film19, grain rotation and coarsening in polycrystalline Al thin film20, dislocation climb in Al/Nb multilayers21 and grain boundary sliding and grain rotation in ceramic nanocomposite22. However there is little in situ TEM evidence on strain hardening in nc metals.

In this study, in situ nanoindentation in a transmission electron microscope was conducted on nc Ni. During multiple loading-unloading cycles, prominent work hardening was observed from quantitative nanoindentation experiment. In parallel, work hardening was found to arise from the formation of abundant L-C Locks both within the grains and at twin boundaries. L-C Locks interacted with twin boundaries through the formation of active partial dislocations. Numerous deformation mechanisms were identified. (See experimental details in methods section).

The nc Ni powders were mixed by roller milling and consolidated by Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) process. Details on the sample processing can be found elsewhere23,24. TEM specimens were prepared through a conventional procedure including mechanical thinning, polishing and ion milling polishing. This typical set of Ni samples has nanocrystalline grains with a bimodal grain size distribution (see Supplementary Fig. S1 in supplementary information). The nanograins accompanied by the bimodal grain size distribution in nc Ni allow enhanced ductility and high mechanical strength25. Growth twins with an average twin spacing of ~30 nm were observed in numerous grains.

Results

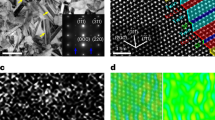

Figure 1a shows the TEM image of two major grains, delineated as G1 and G2 in a typical area selected for in situ nanoindentation study. G1 contains three twin boundaries (TBs), labelled as TB1-TB3. Figures 1b–d show the selected area diffraction (SAD) patterns corresponding to matrix and twin (T1) in G1 and G2. Comparison of Figure 1b and 1d shows the formation of a 30° high angle grain boundary between G1 and G2.

a) TEM image shows the area where in situ nanoindentation experiments were conducted.It shows very obvious grain and twin structures. From the top to bottom, grains, G2 and G1 and twin, T1, are marked. The arrows point at the boundaries between G1, G2 and T1. The SAD patterns were taken from the area of b) grain, G1, c) twin, T1 and d) grain, G2.

To examine dislocation activity during deformation, in situ nanoindentation has been performed. Three indentation (complete loading-unloading experiments) cycles were conducted at exactly the same location as shown in Figure 1a. Figure 2a1–a2 are the video snap shots captured during the first loading cycle before (at 18.48 s) and after the yield point (at 25.29 s) as revealed from the force–displacement (F–D) plot in Figure 3a. Similarly, microstructure evolutions (before and after yielding) for the 2nd and 3rd loading cycles were recorded in Figure 2b1–b2 and 2c1–c2. The corresponding F–D plots are shown in Figure 3b and c. The yield point was determined from the corresponding F–D plots, in which a clear non-linear deformation can be identified. During these experiments, the nanoindenter tip was positioned at the upper right corner and the samples were moving towards the tip with the loading direction marked as white arrows as shown in Figure 2.

During the first loading cycle before yielding (at 18.48s), groups of dislocations on the ( ) and (

) and ( ) slip planes in G1 are observed in the circled area in Figure 2a1. Many of these dislocations form V- shape junctions, which are typical signature of L-C locks. Under indentation these L-C locks are immobile before yielding (up to 22.96 sec). At the yield point, the L-C locks appear to interact with succeeding dislocations and then become unlocked. The unlocked dislocations migrate towards the TB1 during continuous deformation after yielding (25.29 sec in Fig. 2a2). When numerous dislocations approach TB1, new L-C locks form at the twin boundary (Fig. 2b). And the density of dislocations at TB1 is ~7.0 × 1015/m2.

) slip planes in G1 are observed in the circled area in Figure 2a1. Many of these dislocations form V- shape junctions, which are typical signature of L-C locks. Under indentation these L-C locks are immobile before yielding (up to 22.96 sec). At the yield point, the L-C locks appear to interact with succeeding dislocations and then become unlocked. The unlocked dislocations migrate towards the TB1 during continuous deformation after yielding (25.29 sec in Fig. 2a2). When numerous dislocations approach TB1, new L-C locks form at the twin boundary (Fig. 2b). And the density of dislocations at TB1 is ~7.0 × 1015/m2.

During the second loading cycle, dislocation density at TB1 rises continuously to ~1.2 × 1016/m2 by 21.96 sec as shown in Figure 2b1 (for details see supplemental information). By 28.47 sec a majority of dislocations including L-C Locks piled up against TB1 have transmitted through TB1. Correspondingly the F-D plot in Figure 3b shows a clear non-linear deformation, indicating the occurrence of considerable plastic deformation. Additionally the force at the onset of plastic yielding approaches 6.6 μN, greater than that in the first cycle (~4.9 μN).

Finally, in the third cycle, at 22.17 sec, high density dislocations including L-C locks emerge underneath TB1 in T1 (the twinned crystal). The newly formed L-C locks become barriers to succeeding dislocations and applied load continues to increase. At the yield point, ~28 sec as shown in Figure 3c, L-C locks begin to unlock. By 38.29 sec near the maximum load in Figure 3c, L-C Locks are nearly completely annihilated and the TEM image shows dark contrast surrounding a band of forest dislocations resulting from dislocation-L-C Lock interactions in T1 (Fig. 2c2). Prominent load drop is identified in Figure 3c during continuous deformation.

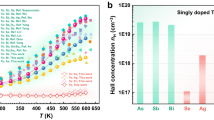

Comparison of multiple consecutive F-D plots in Figure 4 shows that the force at the yield point increases sequentially from ~4.9 to 7.0 μN during the three loading cycles. Consequently given the measured foil thickness and loading depths, we estimate that the yield strength increases from ~1.6 to 2.3 GPa by using a relation described in supplemental information.

Discussions

Work hardening is a complicated plastic deformation phenomenon. Cottrell stated that work hardening is the first phenomenon discovered in studying plasticity of metals and may be the last problem to be solved26. Work hardening deemed necessary for the achievement of ductility, however, is largely absent in a majority of nc metallic materials. But foregoing in situ nanoindentation studies strongly suggest that significant work hardening takes place in nc Ni.

Several salient characteristics can be derived from the in situ studies. First, work hardening may arise directly from the formation of L-C locks in grain interior. L-C locks form the back-bone of dislocation networks and resist the propagation of mobile dislocations. This mechanism has long been postulated and recently received some support from ex situ rolling studies of nc Ni15. The formation of L-C locks arises from the interaction of dislocations on two sets of inclined {111} planes. Second, L-C locks formed within grains were removed at higher stress by mobile dislocations (many of which maybe mobile partials). Recent MD simulations show that mobile Shockley partials can engage stair-rod dislocation in stacking fault tetrahedra (SFTs) and the interaction leads to new mobile partials which then glide on the surfaces of SFTs and lead to decomposition of SFTs27. Hence it is likely that abundant partials emitted from grain boundaries may lead to the removal of L-C locks in grain interior. Third, L-C locks when encountered twin boundaries can lead to even greater work hardening (as indicated by the necessity of higher stress for plastic yield shown in the second loading cycle). The details of interaction of L-C locks with twin boundaries are complicated and at least two scenarios are identified.

We begin by first examining the work hardening mechanism that arises from the interaction of L-C locks with twin boundaries. Figure 5 shows a set of snap shots captured from 22 to 45 sec (after yielding) during the first loading cycle. The area of interest marked by a white box in Figure 5a is near TB1 and the box is enlarged in Figure 5b. By 28.30 sec two dislocations (possibly mobile screw or mixed dislocations), A0 and B from different set of {111} plane intercept at TB1. During continuous indentation at 30.28 sec, the two dislocations interact and an L-C lock forms. At 34.65 sec, A0 vanishes and two new dislocations, A1 and A2, emerge. By 36.87 sec, a new dislocation A3 appears at TB1. By 44.43 sec, these dislocations appear absorbed by TB1.

During the first indentation cycle, evident activity of dislocations (mainly screw or mixed dislocations) at the twin boundary was observed with formation of L-C lock.

a) A snap shot shows the area of interest marked by a white box near TB1. And the enlarged series of movie frames show the interaction between dislocations and twin boundary b) at yield point and c–h) after yield point, with the corresponding i) force-displacement plot.

The interaction mechanism of these dislocations with twin boundaries is shown in a schematic diagram in Figure 6. As shown in Figure 6a–b, two full dislocations, A0 and B, from differently oriented {111} planes form an L-C lock at the twin boundary. Based on the equation  , the formation of Lomer dislocation (at the intercept of L-C locks) can reduce the overall elastic energy of the dislocations (see Supplementary Fig. S5 in supplementary information). The Lomer dislocation formed has a Burgers vector parallel to the electron beam and hence appears as a dot during numerous interaction events.

, the formation of Lomer dislocation (at the intercept of L-C locks) can reduce the overall elastic energy of the dislocations (see Supplementary Fig. S5 in supplementary information). The Lomer dislocation formed has a Burgers vector parallel to the electron beam and hence appears as a dot during numerous interaction events.

Schematic diagrams illustrate the interaction of L-C locks with twin boundaries from the series of movie snap shots in Figure 5.

a) Two full dislocations (possibly screw or mixed dislocations), A0 and B, on different set of {111} planes intercept at TB1. b) As dislocation A0 glides toward dislocation B, an L-C lock is formed at the twin boundary. c) Dislocation A0 dissociates into two partial dislocations, A1 and A2 separated by ~15 nm. d) As the separation is constricted to ~4.5 nm, another dislocation A3 is emitted from the dislocation A1.

A0 then dissociates into two partial dislocations marked with A1 and A2, separated by ~15 nm. The dissociation event occurs at a rate of ~19 nm·s−1 (dividing the separation distance by the time). The force decreases by ~4.8% during the dissociation event. Since the self-stress (line tension) of the dislocation is proportional to its curvature28, the back stress from the forest dislocations in addition to the line tension in dislocation A0 causes it to unbow which allows the perfect dislocation to then separate into leading and trailing partials. After dissociation, the partial dislocation A2 is still associated with the dislocation B. The other partial dislocation A1 appears to be the source for emission of another dislocation, A3. The emission of A3, very likely a screw dislocation, occurs at a rate of 116 nm·s−1. If A3 was to have non-screw dislocation nature, then its emission and migration shall be a type of climb, which typically occurs at a very low rate at room temperature. During the aforementioned events, continuous increase of stress is necessary in general to promote the interaction of L-C locks with twin boundaries and consequently work hardening is achieved.

Next we consider a mechanism that may lead to the transmission of dislocations from L-C locks across twin boundaries. In the second indentation cycle, several snap shots captured from 21 to 33 sec are shown in Figure 7. This period corresponds to the deformation right before the maximum load. Figure 7a shows a box that outlines the area of interest, which is then magnified in Figure 7b (at 21.65 sec). An L-C lock due to interception of A0 and B (likely to be screw or mixed dislocations) is identified. During continuous deformation from 25.71 to 28.23 sec, the contrast of B decays rapidly; meanwhile, a dislocation labelled as B′ emerges from underneath the twin boundary and resides on a (100) plane in the twinned crystal T1. By increasing the applied stress to 2.4 GPa (near 28.56 sec), dislocation A0 vanishes and consequently A1 and A2 appear as shown in Figure 7g. Then dislocation B rapidly passes through the twin boundary and becomes B′ (Fig. 7h). By 32.98 sec, dislocation A1 and A2 also transmit through twin boundary.

a) A snap shot taken during the second indentation cycle shows the area of interest marked by a white box near TB1.And enlarged series of movie frames show interaction between two specific dislocations, A0 and B (likely to be screw or mixed dislocations), resulting in the transmission from L-C locks across twin boundaries, with a detailed analysis as shown in b), c) and d) before yield point and e), f), g) and h) after yield point, with the corresponding i) force-displacement plot.

Figure 8 shows the schematics that illustrate the series of interaction events. Basically the L-C lock forms at twin boundary due to interactions of A0-B dislocations. B gradually transmits through twin boundary and becomes B′ on lower (100) plane, whereas A0 remains intact. The transmission of full dislocation in Ni has been modeled by MD simulation. The simulation shows that under high resolved shear stress, ~3 GPa, a full dislocation will transmit across twin boundary onto the lower {100} plane in the twinned crystal29. At higher stress, A0 dissociates into A1 and A2 as shown in Figure 8b at a velocity of ~12.3 nm·s−1. The dissociation is likely to relieve some of the back stress at the L-C lock and consequently making it easier for B to rapidly transmit across twin boundary as shown in Figure 8c.

Schematic diagrams illustrate the process of dislocation transmission across TB1 from the series of movie snap shots in Figure 7.

a) Two full dislocations, A0 and B, on different sets of {111} planes form an L-C lock at the twin boundary. b) Dislocation A0 dissociates into two partial dislocations, A1 and A2. Meanwhile, c) dislocation B penetrates through the twin boundary and glides on the (100) plane in T1 as the dislocation B′ as released from the back stress at the L-C lock. d) Dislocation B completely penetrates through the twin boundary. Then, dislocation A1 and A2 also pass through the twin boundary.

Twin boundaries are effective barriers to the transmission of dislocations. It has been reported that the interaction of partials with twin boundary may lead to stair rod dislocations, which could resist the transmission of dislocations across twin boundary30. Additionally, the density of residual dislocations stored at the twin boundary increases during indentation (from 6.96×1015/m2 to 1.22×1016/m2). Significant increase in dislocation density has been observed in rolled nt Cu, wherein dislocation density approaches 1016/m2 at a true strain level of 50% or greater31. Consequently high density dislocations may increase the barrier strength of twin boundary to the transmission of dislocations and lead to enhanced work hardening. This in situ nanoindentation study reveals certain mechanisms related to local work hardening events. Further work, such as mesoscale modeling is needed to integrate the observed local work hardening events to global scale. It will necessitate statistically averaging the number of events of such L-C Lock formation per unit volume, the amount of stored dislocations (or slippage - for strain softening) and the frequency at which such unit process takes place. Work is ongoing to make the correlation between the global and local work hardening events.

In summary in situ nanoindentation experiment shows solid evidence for significant work hardening in nc Ni based on sequential loading-unloading cycles. During work hardening, the dislocation density along the TB increases and the yield strength increases gradually by ~40%. Frequent formation of L-C locks was identified in grain interior and along twin boundaries. L-C locks are effective barriers to dislocations and lead to work hardening. Several mechanisms of interaction between L-C locks and twin boundaries were identified. These studies provide important insight to the understanding of plasticity in nc metals.

Methods

Experimental setup

In situ nanoindentation was conducted using an in situ nanoindentation holder (manufactured by NanoFactory, Inc.). In situ TEM analyses were conducted within an analytical electron microscope (JEOL2010) with a point-to-point resolution of 0.23 nm. Images and movies during indentation events were captured using a built-in high resolution CCD camera in the microscope. While the indentation under the TEM column, the sample was controlled in three dimensions by a piezoelectric actuator. To avoid the slip between tip and sample surface, wedge diamond tip (tip angle ~50.5°) for standard load-displacement measurements is used. In situ movies and images were taken during the loading and unloading processes using the experimental setup described in Supplementary Figure S2 from supplementary information. During in situ indentation experiment, the nanoindentation tip was fixed while the sample was moved toward the tip by a piezoelectric stage in a precision movement as fine as 0.1 nm/step. To examine more precise motion of dislocations during work hardening, a maximum depth of 50 nm was used with step length of 0.1 nm/step and holding time of 10 ms. Each loading-unloading cycle spans across 100 seconds, e.g., the loading process occurred at a constant displacement rate continues up to 50 sec, followed by an unloading process at the same rate of 1 nm/sec (the estimated strain rate is 3.6×10−2 s−1 for the first cycle, 4.1×10−2 s−1 for the second cycle and 4.5×10−2 s−1 for the third cycle). While the force was measured along displacement and time, the estimated measurement error was ± 5%.

References

Mecking, H. & Kocks, U. F. Kinetics of flow and strain-hardening. Acta metall. 29, 1865–1875 (1981).

Franciosi, P., Berveiller, M. & Zaoui, A. Latent Hardening in copper and aluminum single crystals. Acta Metall. 28, 273–283 (1980).

Devincre, B., Hoc, T. & Kubin, L. Dislocation mean free paths and strain hardening of crystals. Science 320, 1745–1748 (2008).

Kocks, U. F. & Mecking, H. Physics and phenomenology of strain hardening: the FCC case. Prog. Mater. Sci. 48, 171–273 (2003).

Hall, E. O. The deformation and ageing of mild steel: III. Discussion of results. Proc. Phys. Soc. B 64, 747–753 (1951).

Petch, N. J. The cleavage strength of polycrystals. J. Iron Steel Inst. 174, 25–28 (1953).

Lomer, W. M. A dislocation reaction in the face-centered cubic lattice. Phil. Mag. 42, 1327–1331 (1951).

Cottrell, A. H. The formation of immobile dislocations during slip. Phil. Mag. 43, 645–647 (1952).

Zhang, X. et al. Nanoscale-twinning-induced strengthening in austenitic stainless steel thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 1096–1098 (2004).

Bouaziz, O., Allain, S. & Scott, C. Effect of grain and twin boundaries on the hardening mechanisms of twinning-induced plasticity steels. Scripta Mater. 58, 484–487 (2008).

Afanasyev, K. A. & Sansoz, F. Strengthening in Gold Nanopillars with Nanoscale Twins. Nano Lett. 7, 2056–2062 (2007).

Lu, L., Chen, X., Huang, X. & Lu, K. Revealing the maximum strength in nanotwinned copper. Science 323, 607–610 (2009).

Bulatov, V. V. et al. Dislocation multi-junctions and strain hardening. Nature 440, 1174–1178 (2006).

Budrovic, Z., Swygenhoven, H. V., Derlet, P. M., Petegem, S. V. & Schmitt, B. Plastic deformation with reversible peak broadening in nanocrystalline nickel. Science 304, 273–276 (2004).

Wu, X. L., Zhu, Y. T., Wei, Y. G. & Wei, Q. Strong strain hardening in nanocrystalline nickel. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 205504-1-4 (2009).

Yamakov, V., Wolf, D., Phillpot, S. R., Mukherjee, A. K. & Gleiter, H. Deformation-mechanism map for nanocrystalline metals by molecular-dynamics simulation. Nature Mater. 3, 43–47 (2004).

Shan, Z. W., Mishra, R. K., Syed Asif, S. A., Warren, O. L. & Minor, A. M. Mechanical annealing and source-limited deformation in submicrometre-diameter Ni crystals. Nat. Mater. 7, 115–119 (2008).

Oh, S. H., Legros, M., Kiener, D. & Dehm, G. In situ observation of dislocation nucleation and escape in a submicrometre aluminium single crystal. Nat. Mater. 8, 95–100 (2009).

Minor, A. M., Stach, E. A., Morris, J. W. & Petrov, I. In-situ nanoindentation of epitaxial TiN/MgO (001) in a transmission electron microscope. J. Electron Mater. 32, 1023–1027 (2003).

Jin, M., Minor, A. M., Stach, E. A. & Morris, J. W. Direct observation of deformation-induced grain growth during the nanoindentation of ultrafine-grained Al at room temperature. Acta Mater. 52, 5381–5387 (2004).

Li, N., Wang, J., Huang, J. Y., Misra, A. & Zhang, X. In situ TEM observations of room temperature dislocation climb at interfaces in nanolayered Al/Nb composites. Scripta Mater 63, 363–366 (2010).

Lee, J. H. et al. Grain and grain boundary activities observed in alumina–zirconia–magnesia spinel nanocomposites by in situ nanoindentation using transmission electron microscopy. Acta Mater. 58, 4891–4899 (2010).

Munir, Z. A., Anselmi-Tamburini, U. & Ohyanagi, M. The effect of electric field and pressure on the synthesis and consolidation of materials: A review of the spark plasma sintering method. J. Mater. Sci. 41, 763–777 (2006).

Holland, T. B., Ovid'ko, I. A., Wang, H. & Mukherjee, A. K. Elevated temperature deformation behavior of spark plasma sintered nanometric nickel with varied grain size distributions. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 528, 663–671 (2010).

Zhao, Y. H. et al. High Tensile Ductility and Strength in Bulk Nanostructured Nickel. Adv. Mater. 20, 3028–3033 (2008).

Cottrell, A. H. Dislocations and plastic flow in crystals. (Oxford University Press, London, 1953.)

Niewczas, M. & Hoagland, R. G. Molecular dynamics studies of the interaction of a/6 <112> Shockely dislocations with stacking fault tetrahedral in copper. Part II: intersection of stacking fault tetrahedra by moving twin boundaries. Phil. Mag. 89, 727–746 (2009).

Hirth, J. P. & Lothe, J. Theory of Dislocations (Krieger, Malabar, ed. 2, Florida, 1982).

Zhang, X. et al. Effects of deposition parameters on residual stresses, hardness and electrical resistivity of nanoscale twinned 330 stainless steel thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 97, 094302 (2005)

Zhu, Y. T. et al. Dislocation–twin interactions in nanocrystalline fcc metals. Acta Mater. 59, 812–821 (2011).

Anderoglu, O. et al. Plastic flow stability of nanotwinned Cu foils. Int. J. Plasticity 26, 875–886 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by the Office of Naval Research (under Dr Lawrence Kabacoff; Contract number: N00014-08-0510). Mukherjee thanks the funding support from National Science Foundation (NSF-DMR-0703884). Zhang acknowledges funding support from National Science Foundation (NSF-0644835).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H.L. prepared the TEM sample, conducted in situ TEM nanoindentation and analyzed the data. T. B. H. and A. K. M. prepared the bulk nc nickel sample with SPS system. J. H. L., X. Z. and H.W. planned the experiments and prepared the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and contributed to revising the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Movie 1

Supplementary Information

Movie 2

Supplementary Information

Movie 3

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J., Holland, T., Mukherjee, A. et al. Direct observation of Lomer-Cottrell Locks during strain hardening in nanocrystalline nickel by in situ TEM. Sci Rep 3, 1061 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01061

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01061

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.