Abstract

Severe bradycardia/bradyarrhythmia following coadministration of the HCV-NS5B prodrug sofosbuvir with amiodarone was recently reported. Our previous preclinical in vivo experiments demonstrated that only certain HCV-NS5B prodrugs elicit bradycardia when combined with amiodarone. In this study, we evaluate the impact of HCV-NS5B prodrug phosphoramidate diastereochemistry (D-/L-alanine, R-/S-phosphoryl) in vitro and in vivo. Co-applied with amiodarone, L-ala,SP prodrugs increased beating rate and decreased beat amplitude in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs), but D-ala,RP produgs, including MK-3682, did not. Stereochemical selectivity on emerging bradycardia was confirmed in vivo. Diastereomer pairs entered cells equally well, and there was no difference in intracellular accumulation of L-ala,SP metabolites ± amiodarone, but no D-ala,RP metabolites were detected. Cathepsin A (CatA) inhibitors attenuated L-ala,SP prodrug metabolite formation, yet exacerbated L-ala,SP + amiodarone effects, implicating the prodrugs in these effects. Experiments indicate that pharmacological effects and metabolic conversion to UTP analog are L-ala,SP prodrug-dependent in cardiomyocytes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiac safety concerns about intracellular accumulation of nucleos(t)ide inhibitors arose in the context of failed clinical trials, with the hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5B (HCV-NS5B) inhibitor BMS-9860941,2. Since then, investigations have highlighted putative mechanisms of nucleotide-based toxicities, and new approaches for de-risking have been developed using cellular and biochemical methodologies3. Recent reports of severe bradycardic/proarrhythmic effects following coadministration of the uridine nucleotide analog prodrug sofosbuvir with the class-III antiarrhythmic amiodarone, and perhaps other co-administered drugs, including several direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs), have triggered new cardiac toxicity safety concerns and more detailed preclinical/clinical investigations4. While early reports and editorials suggested these clinical adverse events are mediated by common pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions (DDI), preclinical experiments in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) implicated a novel pharmacodynamic interaction between sofosbuvir and amiodarone, related to potential disruptions in intracellular Ca2+ handling mechanisms5,6,7. Moreover, these observations were extended to Merck Nucleotide Inhibitor-1 (MNI-1), a pronucleotide inhibitor tool compound structurally related to sofosbuvir5. Further, in vivo experiments recapitulating the sofosbuvir:amiodarone clinical cardiac effects have demonstrated that not all HCV-NS5B nucleotide prodrugs share the same DDI liability. Specifically, bradycardia and bradyarrhythmia were not observed in rhesus monkeys when intravenous infusion of MK-3682 was completed after AMIO pretreatment7. In this study, we examine the putative role played by the stereochemistry of the amino acyl and phosphoryl group of HCV-NS5B phosphoramidate prodrugs in the adverse cardiac DDI with amiodarone. To this end, we have systematically compared three uridine analog HCV-NS5B inhibitor prodrugs that display D-ala,RP stereochemistry (Merck nucleotide inhibitors MNI-2, MNI-4 and MK-3682) with their L-ala,SP counterparts (sofosbuvir, MNI-1, and MNI-3, respectively).

A preferred stereochemistry imparting greater safety to phosphoramidate prodrugs could be related to the stereoselectivity of intracellular converting enzymes8,9. Murakami and colleagues showed stereoselectivity of Cathepsin-A (CatA), favoring the L-ala,SP diastereoisomer, and of CES1, favoring the L-ala,RP diastereoisomer10. In addition, the authors demonstrated the L-ala,SP stereochemical configuration provided much greater catalytic efficiency in the clone A replicon assay compared to the L-ala,RP diastereoisomer or compared to the mixture of the two phosphate diastereoisomers, but this was related to selective expression of CatA and little or no expression of CES110. In contrast, little difference was observed in nucleotide triphosphate (NTP) activation in primary human hepatocytes when comparing either phosphate diastereoisomer or the mixture10. Together, these findings indicated redundancy between CatA and CES1 in the metabolism of phosphoramidate prodrugs, but stereochemical specificty in metabolism of the drug by CatA and CES1.

An additional consideration is the tissue-specific expression of intracellular converting enzymes, best characterized in liver or small intestine, involved in first-pass metabolism8,11,12. Current understanding suggests the metabolism of sofosbuvir, and other phosphoramidate L-ala,SP HCV-NS5B nucleotide prodrugs by CatA and CES1 inside hepatocytes results in the formation of a cleavage intermediate metabolite which can be further metabolized by Histidine triad Nucleotide-Binding Protein 1 (HINT-1) to the nucleotide monophosphate. The nucleotide monophosphate is then phosphorylated by intracellular kinases to form the pharmacologically active NTP13,14. Similarly, active NTP metabolite formation from phosphoramidate D-ala,RP prodrugs of uridine monophosphate analogs, such as MK-3682, is via the formation of a cleavage intermediate metabolite that is further metabolized by HINT-1 to the uridine monophosphate analog and subsequently phosphorylated by intracellular kinases to form the pharmacologically active NTP. Cardiac-specific differences in NTP analog accumulation, based on stereochemistry and tissue-restricted expression of enzymes required for production of metabolites, may therefore play a role in the adverse DDI. Alternatively, one could envision an analogous stereochemical interaction between the prodrug and a target completely unrelated to carboxylesterases or NTP conversion, yet to be characterized, that might underlie the adverse cardiac DDI.

Results

Stereochemical specificy of interaction between hepatitis C Virus HCV-NS5B inhibitors and amiodarone in hiPSC-CM syncytia model

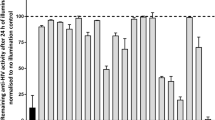

We have previously reported the effect of sofosbuvir or a closely related analog, designated as MNI-1, when co-applied with amiodarone, on the spontaneous beating rate and amplitude of hiPSC-CM syncytia5. Similarly, we have reported how these drugs, when coadministered with amiodarone, produce emergent bradycardia in anesthetized guinea pigs and bradycardia/bradyarrhythmia in conscious, chair-restrained rhesus monkeys7. We used these models to help understand the basis of a clinically observed cardiac DDI associated with severe bradycardia. In this study, we compare systematically three pairs of HCV-NS5B prodrugs, with L-ala,SP or D-ala,RP diastereochemistry: sofosbuvir vs. MNI-2, MNI-1 vs. MNI-4, and MNI-3 vs. MK-3682. Table 1 summarizes the structures of each studied HCV-NS5B prodrug, as well as structures of respective cleavage intermediate metabolites and NTP metabolites that were measured intracellularly. We have observed concentration-dependent effects, at concentrations that approximate the clinical or projected clinical Cmax of amiodarone and each HCV-NS5B prodrug, on spontaneous field potential (FP) rate (Fig. 1a–f) and on impedance (IMP) amplitude (Fig. 2a–f) of hiPSC-CM syncytia, when phosphoramidate L-ala,SP 2′-methyl ribose substituted nucleotide prodrugs were co-applied with amiodarone, and lack of these effects by the corresponding phosphoramidate D-ala,RP 2′-methyl ribose substituted nucleotide prodrugs when co-applied with amiodarone. The measurements shown are steady-state effects at 4 h. As previously reported, the observations in this hiPSC-CM model are paradoxical increases in FP rate, instead of decreases, accompanied by decreases in IMP amplitude5,6. Furthermore, we studied the effects on FP rate and IMP amplitude of “mixed” diastereoisomeric phosphoramidate prodrugs, sharing the nucleoside analog structure of sofosbuvir and MNI-2, but either L-ala,SP (MNI-5) or D-ala,RP (MNI-6) in their stereochemical configuration (structures shown on Supplementary Table 1). Neither one of these prodrugs produced changes in spontaneous FP rate or IMP amplitude in hiPSC-CM syncytia, alone or when combined with amiodarone (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b).

(a–f) Colored bar graphs in each panel show steady state effects produced by increasing concentrations of each prodrug ± amiodarone: (a) Sofosbuvir (SOF). (b) MNI-1. (c) MNI-3. (d) MNI-2. (e) MNI-4. (f) MK-3682. (a–f) Clear bar graphs illustrate measurement with DMSO vehicle or amiodarone alone. Data are normalized to parameters measured at time = 0 (mean ± SEM, n = 6).

(a–f) Colored bar graphs in each panel show steady state effects produced by increasing concentrations of each prodrug ± amiodarone: (a) Sofosbuvir (SOF). (b) MNI-1. (c) MNI-3. (d) MNI-2. (e) MNI-4. (f) MK-3682. (a–f) Clear bar graphs illustrate measurement with DMSO vehicle or amiodarone alone. Data are normalized to parameters measured at time = 0. (mean ± SEM, n = 3). The effect by 11 μM sofosbuvir co-applied with 0.3 μM amiodarone was below the limit of detection (#).

Determination of prodrug, cleavage intermediate metabolite, and NTP metabolite concentration in hiPSC-CMs

Table 2 summarizes the concentrations of prodrug, cleavage intermediate metabolite and NTP metabolite extracted from hiPSC-CMs incubated in multi-well plates for 30 min and 4 h with various phosphoramidate L-ala,SP and D-ala,RP 2′-ribose substituted HCV-NS5B nucleotide prodrugs, alone (10 μM) or in combination with amiodarone (0.3 μM). Each experimental condition represents mean ± SEM (n = 3). For sofosbuvir and MNI-1, L-ala,SP prodrugs, the concentration of cleavage intermediate metabolite accumulated to 8–10 fold of prodrug concentration after 4 h. For MNI-3, the other L-ala,SP prodrug examined, the concentration of cleavage intermediate metabolite accumulated to 50 fold of prodrug concentration after 4 h. Concentrations of NTP metabolite were undetectable at 30 min, increasing by 4 h, as shown on Table 2. In contrast, there were no detectable levels of cleavage intermediate metabolite or NTP metabolite following application of any of the D-ala,RP prodrugs. Coadministration of amiodarone showed no profound impact on the concentrations of L-ala,SP prodrug, cleavage intermediate metabolite or NTP metabolite, or in the concentrations of D-ala,RP prodrug measured, conmensurate with the observed FP rate or IMP amplitude effects (Figs 1a–f and 2a–f).

We directly compared the time courses of the pharmacodynamic effects (Fig. 3a) and pharmacokinetic effects (Fig. 3b) of sofosbuvir (1.0, 3.0, and 10.0 μM) and its D-ala,RP counterpart, MNI-2 (10 μM), alone or in combination with amiodarone (0.3 μM) over an 18-h period. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic measurements (beating rate and amplitude monitored by the fluctuating IMP signal in RTCA Cardio platform) were obtained from the same hiPSC-CM plates. Spontaneously beating hiPSC-CM syncytia were monitored for 0.5 h, 1.5 h, 4 h, and 18 h prior to harvest for analysis of intracellular accumulation of the prodrug, the cleavage intermediate metabolite, and NTP. Figure 3a plots the time course of effects on IMP-measured beating rate and IMP amplitude for the various conditions tested. The D-ala,RP prodrug MNI-2 combined with amiodarone failed to evoke changes over each drug alone. In the presence of 0.3 μM amiodarone, the L-ala,SP prodrug sofosbuvir effected robust, concentration-dependent changes in both beating rate (+146% ± 11% at 10 μM) and amplitude (−97% ± 2% at 10 μM). Figure 3b (top) shows comparable intracellular accumulation of the two prodrugs applied at the same concentration (10 μM). Figure 3b also shows the accumulated intracellular concentrations of the cleavage intermediate metabolite (middle) and final NTP (bottom). As mentioned above, no measurable concentrations of cleavage intermediate metabolite or NTP were observed following application of MNI-2, suggesting a lack of metabolism for this D-ala,RP prodrug in hiPSC-CMs. When intracellular concentrations of sofosbuvir and metabolites were compared to the time course of the sofosbuvir + amiodarone dependent beating rate and amplitude measured by fluctuating IMP in the RTCA Cardio platform, the sofosbuvir prodrug concentration displayed the most closely matching pharmacokinetic time course. The steadily rising concentrations of the cleavage intermediate metabolite, and the late onset of measurable accumulation of NTP over the 18-h time course, argue for a putative secondary role for these metabolites in the observed pharmacodynamic effects.

(a) Effects on beating rate and amplitude, monitored for the various conditions on the fluctuating IMP signal in the RTCA Cardio platform for up to 18 h. Data are normalized to parameters measured at time = 0 (mean ± SEM, n = 3). (b) Concentrations of prodrugs (top), cleavage intermediate metabolite (middle) and NTP (bottom). Cardiomyocytes were harvested for prodrug or metabolite extraction at 0.5 h, 1.5 h, 4 h, and 18 h post-application of prodrugs, alone and/or combined with amiodarone (mean ± SEM, n = 3). Transient overshoots over steady state responses (a) and initial prodrug accumulation over steady state levels (b) could be related to the application of prodrug as a 37X bolus in this particular study. Measurements below the level of quantitation (BLOQ, panel b) are shown at the appropriate time points, simply to illustrate that they were attempted.

In addition, when the “mixed” stereoisomers of sofosbuvir, MNI-5 and MNI-6, described in the previous section, were studied for their ability to accumulate cleavage intermediate metabolite or NTP metabolite, we observed that prodrug levels were accumulated to similar levels than sofosbuvir or MNI-2 (Supplementary Table 1). Surprisingly, we observed that concentration of cleavage metabolite intermediate for one of these prodrugs, MNI-5, L-ala,RP in its stereochemistry, reached measurable levels after 4-h incubation, albeit ~80% reduced compared to those accumulated by incubation of sofosbuvir, its corresponding L-ala,SP prodrug, yet distinct from levels below the limit of quantitation detected for MNI-2, its corresponding D-ala,RP prodrug (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1).

Coadministration of MNI-2 and amiodarone did not cause bradycardia in vivo

The heart rate (HR) effects of MNI-2 alone or in combination with amiodarone were evaluated in ketamine/xylazine-anesthetized, male Dunkin-Hartley guinea pigs. Administration of cumulative IV infusion dose of 2.5 mg/kg amiodarone alone or 10 mg/kg MNI-2 alone decreased HR by −7% and −3% (% change from baseline), respectively (Fig. 4a). Coadministration of these IV doses of MNI-2 and amiodarone did not result in a greater decrease in HR than predicted by either agent alone (−9% vs.−7% and −3% for each agent alone). Plasma levels of MNI-2, MNI-2 cleavage intermediate metabolite, and amiodarone were not different among treatment groups (Supplementary Table 2).

(a) Effects of successive 30-min IV infusions of MNI-2 alone (4, 2, 2, then 2 mg/kg/30 min) or in combination with amiodarone (1, 0.5, 0.5, thn 0.5 mg/kg/30 min), on HR (expressed as a % change [%CH] from baseline) in anesthetized, male guinea pigs. (b) Effects of IV infusion of MNI-2 (4, then 2 mg/kg/30 min) alone or after prior administration of IV amiodarone (AMIO, 3 mg/kg/30 min), expressed as a % change [%CH] from baseline) in conscious, male rhesus monkeys. Dotted line represents the maximum % change from baseline in HR as previously reported7.

There was no effect of IV infusion of MNI-2, alone or after prior administration of amiodarone, on HR in conscious male, restrained rhesus monkeys (Fig. 4b). Plasma concentration of MNI-2 and amiodarone at the end of the MNI-2+amiodarone experiment were 3048 ± 413 ng/mL and 402 ± 23 ng/mL, respectively. In addition, IV infusion of MNI-2 alone or after pretreatment with amiodarone did not result in MBP or PR, QRS, QT ECG interval changes (data not shown).

Furthermore, cardiac tissues from anesthetized guinea pigs were collected immediately following the end of the MNI-2 and MNI-2+amiodarone IV infusions to evaluate tissue concentrations of MNI-2 parent prodrug, MNI-2 cleavage intermediate metabolite, and MNI-2-NTP metabolite (Supplementary Fig. 1). We previously showed that cardiac sofosbuvir concentrations were not higher in anesthetized guinea pigs following cummulative IV administration of sofosbuvir or sofosbuvir + amiodarone (~6 nmol/g tissue) compared to sofosbuvir alone (~8 nmol/g tissue)7. In agreement with the in vitro data on hiPSC-CM syncytia, D-ala,RP MNI-2 did not produce detectable levels of cleavage intermediate metabolite or NTP metabolite, while L-ala,SP sofosbuvir did (Supplementary Fig. 1). Finally, sofosbuvir cleavage intermediate and NTP metabolites were not higher in cardiac tissues from anesthetized guinea pigs administered sofosbuvir + amiodarone vs. sofosbuvir alone (Supplementary Fig 1).

Effect of CatA inhibitors in hiPSC-CM syncytia

Figure 5 shows the effects of CatA inhibitor ebelactone B (Ebel) and a novel, more selective CatA inhibitor, designated as compound 2a, SAR1, or SAR16465315,16,17, on the previously described synergistic effects by L-ala,SP prodrugs in hiPSC-CM syncytia on FP rate and IMP amplitude measured in the CardioECR platform. To maximize the effects of CatA inhibitors, hiPSC-CM syncytia were pre-incubated with these reagents for 30 minutes prior to a second addition at time = 0, alone or combined with other test agents. Figure 5a shows the results of this treatment with 3 μM or 10 μM Ebel, on the normalized, time-dependent effects on FP rate (top) and IMP amplitude (bottom) in spontaneously beating hiPSC-CM syncytia by 3 μM sofosbuvir, alone or co-administered with 0.3 μM amiodarone. Figure 5b shows the results of this treatment with 3 μM Ebel, on the normalized, time-dependent effects on FP rate and IMP amplitude in spontaneously beating hiPSC-CM syncytia by 0.3 μM MNI-1, alone or co-administered with 0.3 μM amiodarone. Figure 5c shows the results of this treatment with 30 μM SAR164653, on the normalized time-dependent effects on FP rate and IMP amplitude in spontaneously beating hiPSC-CM syncytia by 1 μM MNI-1, alone or co-administered with 0.3 μM amiodarone. Overall, Ebel demonstrated a concentration-dependent exacerbation of the effects associated with L-ala,SP prodrug + amiodarone. SAR164653 showed a similar effect on L-ala,SP prodrug MNI-1, suggesting this exacerbation can be attributed to a marked CatA inhibitory activity. Monitoring baseline IMP during all these studies revealed no evidence of generalized cytotoxity.

(a) Effects of Ebel on the DDI between sofosbuvir+amiodarone. (b) Effects of Ebel on the DDI between MNI-1 + amiodarone. (c) Effect of CatA inhibitor SAR164653 (SAR1) on the DDI between MNI-1 + amiodarone. (a–c) FP rate (left) and IMP amplitude (right) were monitored, measured and normalized to the responses at time = 0. Appropriate controls in each panel show the baseline effects of DMSO vehicle alone, amiodarone alone, and HCV NI prodrug alone.

We conducted complementary measurements of intracellular concentrations of sofosbuvir prodrug, cleavage intermediate metabolite, and NTP metabolite in hiPSC-CMs. Ebel transiently inhibited the formation of the sofosbuvir cleavage intermediate metabolite to levels below the limit of quantitation after 30 min incubation (Supplementary Table 3). Similarly, CatA inhibitor SAR164653 decreased, with concentration and time dependence, the concentration of sofosbuvir cleaveage intermediate metabolite intermediate (Supplementary Table 4). Therefore, while CatA inhibitors reduced, as expected, L-ala,SP prodrug cleavage intermediate metabolite levels, they did not reduce, but rather, exacerbated the observed FP rate and IMP amplitude effects in spontaneously beating hiPSC-CMs.

Comparison of MNI-1 and MNI-4 effects on Ca2+ influx in HEK-293 cells heterologously expressing Cav1.2 or Cav1.3 channels

In a recently published study, we established a link to an intracellular Ca2+-handling mechanism in hiPSC-CM syncytia, and have shown that Ca2+ influx in Cav1.2 /HEK-293 cells similarly models this synergistic effect5. We reported shifts in the concentration response of Ca2+ influx inhibition by amiodarone alone with L-ala,SP pronucleotide MNI-1 co-applied at 1 μM and 3 μM (IC50 values shifting from 0.79 μM, to 0.47 μM and 0.29 μM, respectively). In the current study, we extend the findings of diastereoisomeric specificity into the Cav1.2/HEK-293 cell line model, by examining the effects of the diastereoisomeric counterpart of MNI-1 (L-ala,SP), designated as MNI-4 (D-ala,RP), on the concentration-dependent, Ca2+ influx-inhibition by amiodarone. The IC50 value of MNI-1 alone in this model is >150 μM (21% inhibition at maximal tested concentration = 150 μM), while that of MNI-4 is approximately 36 μM (27–45 μM in repeat tests, n = 3 for each test). Amiodarone, in contrast, potently inhibits Cav1.2 Ca2+ influx with IC50 value approx. 1 μM. Figure 6a illustrates the inability of 1 μM or 3 μM MNI-4 to produce a leftward shift on the inhibitory activity of amiodarone (IC50 = 1.1 μM for all 3 conditions). In addition, we directly compared MNI-1 and MNI-4 on the inibitory activity of amiodarone on Cav1.3/HEK-293 influx. Figure 6b, illustrates diastereoisomeric specificity on the inhibitory activity of amiodarone on Cav1.3 Ca2+ influx.

(a) Lack of effect of MNI-4 on the Ca2+ influx inhibition produced by amiodarone on Cav1.2/HEK-293 cells. (b) Effect of MNI-1 and lack of effect of MNI-4 on the Ca2+ influx inhibition produced by amiodarone on Cav1.3/HEK-293 cells. IC50 values = 0.53 μM, 0.62 μM, and 0.19 μM for amiodarone alone, 1 μM MNI-4 + amiodarone, and 1 μM MNI-1 + amiodarone, respectively.

Discussion

The major finding in this study was the lack of DDI with amiodarone shown by D-ala,RP diastereoisomeric phosphoramidate HCV-NS5B prodrugs, including MK-3682, in preclinical in vitro and in vivo models. This finding was associated with the lack of metabolic activation for all D-ala,RP prodrugs tested in hiPSC-CMs, and for MNI-2, in comparison to sofosbuvir, in guinea-pig hearts. Three pairs of diastereoisomeric prodrugs, including sofosbuvir (L-ala,SP) vs. MNI-2 (D-ala,RP), MNI-1 (L-ala,SP) vs. MNI-4 (D-ala,SP), and MNI-3 (L-ala,SP) vs. our company’s development compound MK-3682 (D-ala,RP), were compared in hiPSC-CMs. We have previously reported the paradoxical increase in beating rate produced by sofosbuvir and MNI-1, and the concomitant decrease in beat amplitude in this in vitro model5. In these studies, we have documented the reproducible, diastereoisomer-specific effect of phosphoramidate HCV-NS5B prodrugs with varying substituents in the 2′ position of the ribose moiety. In addition, we compared the metabolic activation of these compounds, noting that none of the D-ala,RP prodrugs produced measurable cleavage intermediate or NTP metabolites in the cardiac tissues and hiPSC-CMs examined. We also noted that, in terms of the specific DDI with amiodarone, the intracellular measurements did not reveal large differences in the concentration of cleavage metabolite or NTP formed in the absence or presence of amiodarone, proportional with the observed pharmacological effects. We showed that a specific configuration at both diastereoisomeric centers of the phosphoramidate prodrugs, at the alanyl- and phosphoryl- groups (L-ala,SP), is required for the effects reported in spontaneously beating hiPSC-CM syncytia, and found reduced, yet measurable cleavage intermediate metabolite accumulation for the L-ala,RP prodrug, despite its lack of effects in spontaneous beating activity.

The present studies suggest that cleavage metabolites produced by CatA or other CES enzymes active in cardiomyocytes do not play a major role in the adverse DDI with amiodarone. Although there is redundancy in the carboxylesterases that may play a role in the activation of phosphoramidate prodrugs in cardiomyocytes8,18, expression data and additional evidence argue for a relevant action by CatA19. While CatA inhibitors (Ebel and SAR164653) showed expected inhibitory effects on the formation of cleavage intermediate metabolite in hiPSC-CMs, they did not attenuate the effects on FP rate and IMP amplitude, as could have been expected, but rather exacerbated these effects, consistent with increased prodrug levels with CatA inhibition. Together, the observations reported in this study emphasize the specific role of L-ala,SP prodrug in the adverse effects associated with the amiodarone DDI. Additional information, some of it previously reported5, include: fast onset of effect associated with the DDI on hiPSC-CM Ca2+ transients (FDSS) and FP rate (CardioECR); fast washout of FP rate effect (data not shown); fast effects associated with the DDI on Ca2+ influx and Ca2+ currents in heterologous expression systems. An alternative mechanism for the effect could be an uncharacterized metabolite produced in a stereospecific manner.

We have recently reported the hemodynamic effects of sofosbuvir and MNI-1 in the presence of amiodarone, in anesthetized guinea pigs and in conscious rhesus monkeys, and the lack of these adverse effects by MK-36827. With the current studies, we extend the lack of in vivo effects previously reported for MK-3682 to MNI-2, the D-ala,RP counterpart of MNI-1. IV administration of MNI-2 alone or with amiodarone did not result in greater than additive decreases in HR in anesthetized guinea pigs or conscious rhesus monkeys. MNI-2 parent prodrug and MNI-2 cleavage intermediate metabolite plasma concentrations were similar in anesthetized guinea pigs treated with MNI-2 and MNI-2+amiodarone. Likewise, MNI-2 parent prodrug cardiac tissue concentrations were similar in guinea pigs treated with either MNI-2 or MNI-2 + amiodarone. However, both the MNI-2 cleavage intermediate metabolite and MNI-2 NTP metabolite were below the limit of quantification in guinea-pig hearts treated with either MNI-2 alone or the combination of MNI-2 and amiodarone. In contrast, cleavage intermediate metabolite and NTP were present in hearts from sofosbuvir and sofosbuvir + amiodarone treated guinea pigs (Supplementary Fig. 1). Thus, the preclinical in vivo findings support the systematic findings in the hiPSC-CM syncytia model, while providing correct directionality (bradycardia vs increased FP rate in vitro), as a translational anchor predictive of clinical cardiac safety for MK-3682 and other D-ala,RP phosphoramidate prodrugs.

The stereospecificity associated with adverse cardiac effects in our preclinical in vitro and in vivo models was also shown to extend to the simpler, Ca2+ channel overexpression system; a model we previously demonstrated to be sensitive to L-ala,SP + amiodarone-dependent effects exemplified by MNI-15. In this study, we showed that MNI-4, the D-ala,RP counterpart of MNI-1, fails to produce a leftward shift in the inhibitory effect of amiodarone, in contrast to MNI-1. This diastereoisomeric specificity was not only revealed on influx across Cav1.2, the predominant L-type Ca2+ channel in cardiomyocytes, but also on influx across the Cav1.3 isoform, specific to SA nodal cells20,21,22. The important role of Cav1.3 channels on sinus rhythm has been established, not only on mouse knockout models phenotypically exhibiting bradycardia20, but also in human Cav1.3 channelopathies associated with bradycardia and congenital deafness22,23. Together, these findings confirm our previously reported results in Cav1.2 HEK293 overexpressing cells, and provide additional insights into an ion flux-based mechanism behind the severe bradycardia associated with these L-ala,SP HCV-NS5B DAAs and amiodarone. In hiPSC-CMs, we hypothesize a role for intracellular Ca2+ in the DDI, evidenced by the action of agents affecting sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ load (i.e.,ryanodine and thapsigargin) or NCX1 function (i.e. SEA 0400 and Ca2+ clearance) on the combined action of MNI-1 + amiodarone. In the simpler system of Cav1.2 HEK293 cells, we dissected the DDI on Cav1.2 channels, as a shift by MNI-1 in the inhibitory effect of amiodarone on calcium influx in intact cells, and further characterized it as a shift in the inhibition by amiodarone of Cav1.2 channel inactivation in whole cell patch clamp experiments using the perforated patch technique. We hypothesize a role for intracellular Ca2+ and L-type Ca2+ channel inactivation similar to that classically characterized in guinea pig ventricular myocytes24. Via Ca2+-sensitive inactivation, the L-type Ca2+ channel integrates both sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release, local and global Ca2+ entry, and membrane potential changes; the effect of the nucleoside in synergy with amiodarone may involve one of these mechanisms of the control of Ca2+ near the cytoplasmic face of the channel25. One could also envision a potential adverse effect of L-ala,SP prodrugs on hearing, through similar interactions with Cav1.3 channels in auditory hair cells. We explain the apparent inability by other investigators to detect DDI-associated effects on heterologously expressing Cav1.2 cell lines6, primarily in terms of the voltage dependence of the effect, and potential methodological differences, as previously reported5.

Evidence of stereoselective metabolism by CatA and CES1 was detected for sofosbuvir and its L-ala,RP counterpart in a replicon system10. In the current studies, we have revealed the importance of the L-ala,SP vs. D-ala,RP stereospecificity in determining adverse cardiac DDI effects. Our recently published data provided mechanistic insights and clinical translatability5,7, and also initial evidence that not all DAA HCV-NS5B agents exhibit this cardiac DDI7. This study shows that the D-ala,RP configuration, exemplified by MK-3682, MNI-2, and MNI-4, does not present the adverse pharmacodynamic interactions detected with the L-ala,SP pronucleotide diastereochemistry, exemplified by sofosbuvir, MNI-1, and MNI-3, in cardiomyocytes. In addition, the D-ala,RP pronucleotides appear metabolically inactive toward NTP conversion in cardiomyocytes. MK-3682 has been shown to be active in patients infected with the human hepatitis C virus and treated with MK-3682 alone or in combination with other HCV viral therapies26,27.

Methods

Drugs

Diastereoisomeric pairs of HCV-NS5B inhibitor prodrugs were synthesized in-house for research purposes, as follows: phosphoramidate L-ala,SP or D-ala,RP 2′-fluoro-2′-methyl ribose “substituted nucleotide prodrug (i.e., sofosbuvir: isopropyl (2S)-2-[[[(2R,3R,4R,5R)-5-(2,4-dioxopyrimidin-1-yl)-4-fluoro-3-hydroxy-4-methyl-tetrahydrofuran-2-yl]methoxy-phenoxy-phosphoryl]amino]propanoate, or MNI-2: isopropyl (2R)-2-[[[(2R,3R,4R,5R)-5-(2,4-dioxopyrimidin-1-yl)-4-fluoro-3-hydroxy-4-methyl-tetrahydrofuran-2-yl]methoxy-phenoxy-phosphoryl]amino]propanoate); phosphoramidate L-ala,SP or D-ala,RP 2′-alkyne-2′-methyl ribose substituted nucleotide prodrug (i.e., MNI-1: isopropyl (2S)-2-[[[(2R,3R,4R,5R)-5-(2,4-dioxopyrimidin-1-yl)-4-ethynyl-3-hydroxy-4-methyl-tetrahydrofuran-2-yl]methoxy-phenoxy-phosphoryl]amino]propanoate, or MNI-4: isopropyl (2R)-2-[[[(2R,3R,4R,5R)-5-(2,4-dioxopyrimidin-1-yl)-4-ethynyl-3-hydroxy-4-methyl-tetrahydrofuran-2-yl]methoxy-phenoxy-phosphoryl]amino]propanoate); phosphoramidate L-ala,SP or D-ala,RP 2′-chloro-2′-methyl ribose substituted nucleotide prodrug (i.e., MNI-3: isopropyl (2S)-2-[[[(2R,3R,4R,5R)-4-chloro-5-(2,4-dioxopyrimidin-1-yl)-3-hydroxy-4-methyl-tetrahydrofuran-2-yl]methoxy-phenoxy-phosphoryl]amino]propanoate, or MK-3682: isopropyl (2R)-2-[[[(2R,3R,4R,5R)-4-chloro-5-(2,4-dioxopyrimidin-1-yl)-3-hydroxy-4-methyl-tetrahydrofuran-2-yl]methoxy-phenoxy-phosphoryl]amino]propanoate). Table 1 shows the designation and chemical structure of all the phosphoramidate prodrugs compared as diastereochemical pairs in this study. In addition, “mixed” stereoisomers L-ala,RP or D-ala,SP 2′-fluoro-2′-methyl ribose substituted nucleotide prodrugs were synthesized in-house for additional mechanistic studies, and designated as MNI-5 or MNI-6, respectively (Supplementary Table 1).

Amiodarone used for in vitro studies was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Amiodarone used for in vivo studies was obtained as the clinical IV formulation from Mylan Laboratories (NDC 67457-153-18) and diluted with 5% dextrose as needed. Ebelactone B was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences, Inc. (Farmingdale, NY, USA) and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX, USA). CatA inhibitor SAR164653 (also known as compound 2a, or SAR1)15,16,17 was synthesized in house for research purposes.

RTCA Cardio and RTCA CardioECR studies

hiPSC-CMs (iCells®) from Cellular Dynamics International (CDI, Madison, WI, USA) were seeded onto 48-well CardioECR or 96-well Cardio E-Plates® (ACEA Biosciences Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) coated with 10 μg/mL fibronectin (Sigma Aldrich, Catalog# F1141) at 30,000 cells/well, following manufacturer’s recommendations. Cells were maintained in culture (37 °C, 5% CO2) for a period of 14 days with iCell Maintenance® media (CDI, Madison, WI, USA) exchanged every 2–3 days. Compound addition was only performed on or after Day 14 following cell seeding.

Compound stock solutions were prepared in 100% DMSO or H2O. On the day of compound addition, the media was exchanged with fresh iCell Maintenance® media and allowed to equilibrate for at least 3 h in the incubator. The plates were read on an xCELLigence® RTCA CardioECR or RTCA Cardio (ACEA Biosciences Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Control pre-reads to establish a baseline were recorded for at least 45 minutes (4 reads at 15-min intervals) prior to compound addition. The compound stock solutions were diluted into iCell Maintenance® media and quickly added to the plate. The plate was continuously monitored for at least 18 h following compound addition. IMP data were sampled at 12 ms (83 Hz), while FP rate data were collected at 0.1 ms (10 KHz). Attachment, growth and viability of syncytia were monitored by means of the baseline IMP signal, as previously described28. IMP and FP signals were only interpreted if the baseline IMP was maintained throughout the measurement period (usually ≤18 hrs) at ≥70% of the value before test compound application (pre-read value).

HEK-293 /Cav1.2 or Cav1.3 assay

The HEK-293 cell line overexpressing Cav1.2 channel proteins was maintained in-house. HEK-293 cells transiently overexpressing Cav1.3 channel proteins were purchased from ChanTest (Charles River Laboratories, Cleveland, OH, USA). The assay was conducted as previously described5. Briefly, on experiment day, cells were incubated with Codex ACTOne® dye (Codex Biosolutions, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA) formulated in PPB buffer containing 25 mM potassium (in mM: 127 NaCl, 25 KCl 0.005 CaCl2, 1.7 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, pH = 7.2 with NaOH), or PPB buffer containing 1 mM potassium (in mM: 151 NaCl, 1 KCl 0.005 CaCl2, 1.7 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, pH = 7.2 with NaOH) for 1 h at room temperature, then test compounds were added for another 30-minute incubation at room temperature with a final volume of 100 μL. The Hamamatsu FDSS/μCell imaging platform simultaneously collected Ca2+ signals from 96-well plates, at a sampling rate of 16 Hz for 20 seconds as baseline, then a trigger buffer (containing in mM: 119 NaCl, 25 KCl, 4 CaCl2, 1.7 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, pH = 7.2 with NaOH) was added using the dispenser of the FDSS/μCell instrument to generate Ca2+ transient for 40 seconds. The peak amplitude within the latter 40 seconds minus the average amplitude of the first 20 seconds is the final Ca2+ transient response of each well. Average responses from wells treated with 10 μM nifedipine (reference CCB) was used as 100% inhibition (Rmax); and average responses from wells treated with 0.1% DMSO was set as 0% inhibition (Rmin). Relative response of each well was calculated as follows:

Measurement of intracellular prodrug, cleavage intermediate metabolite, and NTP metabolite concentrations

Approximately 18 h before dosing, iCell hiPSC-CMs were switched to iCell cardiomyocyte maintenance media free of Penicillin/Streptomycin. Cells were exposed to vehicle control (0.1% DMSO) or 10 μM of each HCV-NS5B prodrug prepared in the same maintenance media for 0.5 h, 1.5 h, 4 h, and 18 h. A separate set of cells were dosed with 10 μM of prodrug + 0.3 μM amiodarone (final DMSO concentration in all dosing conditions were 0.1%). After the corresponding treatment, cells were washed 2x with 200 μL of ice-cold magnesium- and calcium-free PBS buffer. Cells were then lysed in 100 μL of ice-cold lysis solution (70/30 methanol/water containing 20 mM EDTA and 20 mM EGTA, pH 8) by pipetting up and down 5 times. Plates were sealed and transferred on dry ice for determination of prodrug, cleavage intermediate metabolite, and NTP metabolite concentrations. Intracellular prodrug concentrations were measured using a reversed phase HPLC- high resolution mass spectrometry method. A dimethylhexylamine based ion-pairing HPLC-MS/MS method was used to measure intracellular cleavage intermediate metabolite and NTP metabolite concentrations. Intracellular concentrations (pmol/million cells) of prodrug, cleavage intermediate metabolite, and NTP metabolite were quantitated against calibration standards of the same analytes prepared from control iCell hiPSC-CM lysates. The structures of each of these species are presented in Table 1.

For prodrug analyses, full scan high resolution mass spectrometry data was collected using an Exactive™ Orbitrap mass spectrometer with an electrospray source operated in the positive ion mode. Prodrug chromatograms were extracted from full scan high resolution mass spectrometry data for the masses indicated in Supplementary Table 5. Absence of endogenous interference(s) was verified by extracting the same ion from full scan high resolution mass spectrometry chromatograms of unspiked control cell lysates. For the cleavage intermediate metabolite and NTP metabolite an electrospray MS/MS method run on a SCIEX API 4000 mass spectrometer with turboV ionspray source was used in negative ion mode monitoring the transitions indicated in Supplementary Table 5. Absence of endogenous interference(s) was verified by monitoring of the same MRM transitions for unspiked control cell lysates. Measured intracellular prodrug, cleavage intermediate metabolite, and NTP metabolite concentrations (in pmol/million cells units) were tabulated (Table 2).

In vivo Studies

All animal studies were conducted in accord with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, Commission on Life Sciences, National Research Council, 2011) and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at MRL, Merck & Co. (West Point, PA).

Anesthetized guinea pigs

Adult, male Dunkin-Hartley guinea pigs (350–550 g) were anesthetized and instrumented as previously described7,29. The effects of HCV prodrug alone or in combination with amiodarone on arterial BP, HR, electrocardiogram (ECG) intervals were then evaluated in separate studies, as follows: MNI-2 (n = 4) or amiodarone (n = 5) was administered separately as 4 sequential 30-min IV infusions of 4, 2, 2 and 2 mg/kg (cumulative dose of 10 mg/kg). Then, these doses of MNI-2 were co-administered with IV amiodarone (1, 0.5, 0.5, 0.5 mg/kg/30 min (n = 6). The effects of the vehicle alone (30% Captisol®, 1 mL/kg every 30 minutes, n = 6) and amiodarone (n = 5) were previously reported7, and summary data from that study were plotted to provide comparisons.

Conscious, restrained rhesus monkeys

Arterial BP and ECG waveforms from four chronically-instrumented male, rhesus monkeys (8-16 kg at time of study, approximately 5–8 years of age), were continuously recorded (Notocord-hem™ v 4.3.0.67) and analyzed as described7. Prior to study, animals were acclimated to the restraint chair and the laboratory environment over multiple sessions. At the time of study, animals were weighed, brought to the laboratory in restraint chairs, and following equilibration administered either MNI-2 alone (4 mg/kg/30 min, then 2 mg/kg/30 min), or an IV pretreatment with amiodarone (3 mg/kg/30 min) up to 30-min prior administration of the same dose of MNI-2. MNI-2 was formulated in 30% Captisol®. Since the animals used for these studies were also used previously for studies on HCV-NS5B prodrugs7 and the studies were completed in a similar time frame, vehicle and amiodarone data presented were adapted from data published by Regan et al7. Blood samples (~0.75 mL per time point) were collected in EDTA tubes at the end of each infusion of MNI-2 and an additional sample was collected at the end of the baseline recording for animals pre-administered amiodarone. Samples were placed on wet ice, centrifuged at 4 °C and plasma removed and stored at −70 °C until analysis of concentration of test agents and any metabolites of interest.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Lagrutta, A. et al. Cardiac drug-drug interaction between HCV-NS5B pronucleotide inhibitors and amiodarone is determined by their specific diastereochemistry. Sci. Rep. 7, 44820; doi: 10.1038/srep44820 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Ahmad, T. et al. Cardiac dysfunction associated with a nucleotide polymerase inhibitor for treatment of hepatitis C. Hepatology 62, 409–416 (2015).

Kwagh, J. et al. BMS-986094: Potential Cytotoxicity in Differentiated Human Cardiomyocytes. The Toxicologist: Supplement to Toxicological Sciences. Abstract no. 856 138, 221 (2014).

Baumgart, B. R. et al. Effects of BMS-986094, a Guanosine Nucleotide Analogue, on Mitochondrial DNA Synthesis and Function. Toxicol. Sci. (2016).

Fontaine, H. et al. Bradyarrhythmias Associated with Sofosbuvir Treatment. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 1886–1888 (2015).

Lagrutta, A. et al. Interaction between amiodarone and hepatitis-C virus nucleotide inhibitors in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes and HEK-293 Cav1.2 over-expressing cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 308, 66–76 (2016).

Millard, D. et al. Identification of drug-drug interactions in vitro: a case study evaluating the effects of sofosbuvir and amiodarone on hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes. Toxicol. Sci. 154, 174–182 (2016).

Regan, C. P. et al. Preclinical Assessment of the Clinical Cardiac Drug-Drug Interaction Associated with the Combination of HCV-NI Antivirals and Amiodarone. Hepatology 64, 1430–1441 (2016).

Satoh, T. & Hosokawa, M. Structure, function and regulation of carboxylesterases. Chem. Biol. Interact. 162, 195–211 (2006).

Laizure, S. C., Herring, V., Hu, Z., Witbrodt, K. & Parker, R. B. The role of human carboxylesterases in drug metabolism: have we overlooked their importance? Pharmacotherapy 33, 210–222 (2013).

Murakami, E. et al. Mechanism of activation of PSI-7851 and its diastereoisomer PSI-7977. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 34337–34347 (2010).

Imai, T., Taketani, M., Shii, M., Hosokawa, M. & Chiba, K. Substrate specificity of carboxylesterase isozymes and their contribution to hydrolase activity in human liver and small intestine. Drug Metab Dispos. 34, 1734–1741 (2006).

Xie, M., Yang, D., Liu, L., Xue, B. & Yan, B. Human and rodent carboxylesterases: immunorelatedness, overlapping substrate specificity, differential sensitivity to serine enzyme inhibitors, and tumor-related expression. Drug Metab Dispos. 30, 541–547 (2002).

Kirby, B. J., Symonds, W. T., Kearney, B. P. & Mathias, A. A. Pharmacokinetic, Pharmacodynamic, and Drug-Interaction Profile of the Hepatitis C Virus NS5B Polymerase Inhibitor Sofosbuvir. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 54, 677–690 (2015).

Sofia, M. J. et al. Discovery of a beta-d-2′-deoxy-2′-alpha-fluoro-2′-beta-C-methyluridine nucleotide prodrug (PSI-7977) for the treatment of hepatitis C virus. J. Med. Chem. 53, 7202–7218 (2010).

Ruf, S. et al. Novel beta-amino acid derivatives as inhibitors of cathepsin A. J. Med. Chem. 55, 7636–7649 (2012).

Tillner, J. et al. Tolerability, safety, and pharmacokinetics of the novel cathepsin A inhibitor SAR164653 in healthy subjects. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 5, 57–68 (2016).

Petrera, A. et al. Cathepsin A inhibition attenuates myocardial infarction-induced heart failure on the functional and proteomic levels. J. Transl. Med. 14, 153 (2016).

Hosokawa, M. et al. Genomic structure and transcriptional regulation of the rat, mouse, and human carboxylesterase genes. Drug Metab Rev. 39, 1–15 (2007).

Jackman, H. L. et al. Angiotensin 1–9 and 1–7 release in human heart: role of cathepsin A. Hypertension 39, 976–981 (2002).

Mangoni, M. E. et al. Functional role of L-type Cav1.3 Ca2+ channels in cardiac pacemaker activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 5543–5548 (2003).

Marionneau, C. et al. Specific pattern of ionic channel gene expression associated with pacemaker activity in the mouse heart. J. Physiol 562, 223–234 (2005).

Mesirca, P., Torrente, A. G. & Mangoni, M. E. Functional role of voltage gated Ca(2+) channels in heart automaticity. Front Physiol 6, 19 (2015).

Baig, S. M. et al. Loss of Ca(v)1.3 (CACNA1D) function in a human channelopathy with bradycardia and congenital deafness. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 77–84 (2011).

Imredy, J. P. & Yue, D. T. Mechanism of Ca(2+)-sensitive inactivation of L-type Ca2+ channels. Neuron 12, 1301–1318 (1994).

Bers, D. M. Calcium cycling and signaling in cardiac myocytes. Annu. Rev. Physiol 70, 23–49 (2008).

Bhagunde, P., Rizk, M. L., Marshall, B., Butterton, J. & Gao, W. Viral dynamics modeling of MK-3682 monotherapy in HCV infected patients. Journal of Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics 42(1) S104–S105 (2015).

Gane, E. J. et al. High efficacy of an 8-week 3-drug regimen of grazoprevir/MK-8408/MK-3682 in HCV genotype 1, 2 and 3-infected patients: SVR24 data from the phase 2 C-crest 1 and 2 studies. Journal of Hepatology 64(2) S759 (2016).

Zhang, X. et al. Multi-parametric assessment of cardiomyocyte excitation-contraction coupling using impedance and field potential recording: A tool for cardiac safety assessment. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods (2016).

Morissette, P. et al. QT interval correction assessment in the anesthetized guinea pig. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 75, 52–61 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The following MRL technical staff provided critical help with the conduct of experiments: Bharathi Balasubramanian, Spencer Dech, Edward Lis, Jin Zhai, Hillary Regan, Jeffrey Travis, Pamela Gerenser, Jianzhong Wen, Kevin Fitzgerald, Shaun Gruver, Philip Troilo, Rodger Tracy. Paul Bulger provided a qualified supply of diastereoisomeric pronucleotides used in this study, and expert assistance with structural information and nomenclature of diastereoisomers. Scott Wolkenberg provided expert assistance with structural information and nomenclature of diastereoisomers. Stephane Bogen, Frank Bennett, Angela Kerekes designed and originally synthesized MNI-1 and MNI-4. Cyril Dousson, Gilles Gosselin were involved with discovery chemistry for MK-3682. Frank Sistare provided expert, critical review of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.L., C.R., H.Z., J.I., K.K., P.M., J.L., and L.L. designed and undertook experiments, and analyzed, interpreted and presented results for group discussions. G.W., C.B., J.D.G. and F.S. provided rationale, background, framework and feedback. H.Z., J.I., K.K., L.L., J.L. and C.R. provided methods, description of results, figures, and tables for the manuscript. A.L. wrote and organized the manuscript, with editorial input from C.R., H.Z., J.I., K.K., P.M., L.L., G.W., C.B., J.L., J.D.G. and F.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors are employees at MRL, Merck & Co, in the preclinical safety assessment area or in the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and drug metabolism area. Our work, including investigative efforts such as this one, supports development of proprietary preclinical candidates. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lagrutta, A., Regan, C., Zeng, H. et al. Cardiac drug-drug interaction between HCV-NS5B pronucleotide inhibitors and amiodarone is determined by their specific diastereochemistry. Sci Rep 7, 44820 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44820

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44820

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.