-

March 11, 2016

Rapid RNA analysis at a single cell level: a PL... -

February 11, 2016

Free to roam: implantable optogenetic devices -

January 23, 2016

The recipe for human serotonin neurons -

January 08, 2016

Designing logical cells to be disease sensors -

December 25, 2015

The synthesis of a bacterial clock -

November 30, 2015

Folding DNA origami for chemotherapy treatments -

November 07, 2015

Gene Editing in the Natural World: Part II -

October 08, 2015

Mining the depths for new anti-biotics -

September 16, 2015

The TRAP technique gets back to basics -

August 28, 2015

A history lesson: induced pluripotent stem cells -

August 07, 2015

Let there be light: Photoactivatable CRISPR-Cas9 -

July 16, 2015

Transparent brains: mining the depths -

June 24, 2015

Restoring sight with the help of optogenetics -

June 02, 2015

Discovering new cell types one at a time -

May 12, 2015

Treating spinal cord injuries with a dual actio... -

April 20, 2015

Reducing carbon: a bacterial approach -

April 06, 2015

Propagating mutations throughout an entire popu... -

March 23, 2015

This is your brain on integrated technology -

February 28, 2015

Gene Editing in the Natural World -

February 08, 2015

Editing the Genome Quickly and Efficiently: Rou... -

January 27, 2015

Editing the Genome Quickly and Efficiently: Rou... -

January 06, 2015

Enhancing our Gut Flora for disease and allergy... -

December 19, 2014

Controlling Neurons Using Light -

June 21, 2014

Where Conscious and Subconscious Meet -

June 07, 2014

Battle of the Genetic Codes -

May 28, 2014

Blog Update -

April 08, 2014

I Attend the 55th Annual Fly Meeting! -

January 06, 2014

Going Viral for the New Year -

October 13, 2013

How to Clone Yourself, Part 2: Stem Cell Reprog... -

September 24, 2013

How to Clone Yourself, Part 1: Start Small -

September 07, 2013

What I’ve Been Doing Lately -

August 06, 2013

Is in vitro meat all it’s cracked up to be? -

July 09, 2013

Engineering in the Wild: Driving Genes into Pop... -

June 17, 2013

Bee vs. Mite! – Puerto Rico’s Honey... -

June 04, 2013

It's in the Honey! - Bee Diet and Defense Again... -

May 21, 2013

Genetic Logic Gates and Flipping DNA -

April 07, 2013

#DROS2013 Day 4 -

April 06, 2013

#DROS2013 Day 3 -

April 05, 2013

#DROS2013 Day 2 -

April 03, 2013

#DROS2013 Day 1 -

March 27, 2013

Watch for it: Tweeting and Blogging from #DROS2013 -

March 13, 2013

Undergrads Launch Genetics Education Website -

March 05, 2013

Viruses swipe bacterial immune system, turn it ... -

February 26, 2013

An Update on Artemisinin -

February 09, 2013

Editing Genomes with the Bacterial Immune System -

January 11, 2013

The One and Only Popular Synthetic Biology Book -

December 30, 2012

Beyond Genetics: DNA in Nanotechnology -

December 25, 2012

Merry Yeast Christmas! -

November 29, 2012

Engineering Viruses is Hard. Let’s Make i... -

November 02, 2012

The Oddness of California Proposition 37 -

October 26, 2012

Bird of the Week: Yellow-Bellied Sapsucker -

October 23, 2012

Sending DNA Messages Inside Viruses -

October 18, 2012

Bird of the Week: Bullfinch -

October 13, 2012

Bird of the Week: Downy Woodpecker -

October 04, 2012

My First Paper: tRNAs as Genetic Switches -

September 29, 2012

Bird of the Week: Chimney Swift -

September 26, 2012

Cheaper Genomes Should Enhance Undergraduate Ed... -

September 20, 2012

Bird of the Week: White-Breasted Nuthatch -

September 14, 2012

Science Literacy for Everyone -

September 14, 2012

Bird of the Week: Indigo Bunting -

September 11, 2012

Molecular Zoo: E. coli RNA Polymerase -

September 08, 2012

Bird of the Week: Canada Goose -

August 31, 2012

Digital Data Storage in DNA -

August 29, 2012

Bird of the Week: Double Crested Cormorant -

August 24, 2012

Modular Transcription Factors for Eukaryotic Sy... -

August 19, 2012

Bird of the Week: Barn Swallow -

August 09, 2012

Bird of the Week: Common Raven -

August 07, 2012

Molecular Zoo: The TALE’s Tale -

July 30, 2012

Artificial Beginnings: Understanding the Origin... -

July 24, 2012

What the Simulated Cell Actually Means -

July 01, 2012

Zinc Fingers: An Emerging Tool for Gene Therapy -

June 18, 2012

Your Friend the Sequence Logo -

June 07, 2012

In Living Memory: the First Steps toward Geneti... -

May 28, 2012

High-Level Control of Synthetic Systems: The Ge... -

May 07, 2012

Final Exams Beckon... -

May 02, 2012

Artemisia annua: A Vital Partner in the Global ... -

April 22, 2012

Synthetic Nucleic Acids: Beyond DNA and RNA -

April 08, 2012

Horizontal Gene Transfer: A Force for Bacterial... -

March 12, 2012

Chemicals Responsible for Bee Scouting Behavior... -

February 18, 2012

DNA Nanorobot Targets Cells for Molecular Delivery -

January 22, 2012

Seaweed Biofuel, #ArsenicLife, and Synthetic Bi... -

January 14, 2012

Soldier Bees -

January 06, 2012

Synthetic Biology is on its Way to Treating Hum... -

December 25, 2011

Computer Controlled Yeast and an E. coli LCD Sc... -

November 24, 2011

Genomes at the Thanksgiving Table -

November 06, 2011

What can Synthetic Biology Teach us About Basic... -

October 29, 2011

What can Synthetic Biology Teach us About Basic... -

October 16, 2011

What can Synthetic Biology Teach us About Basic... -

October 11, 2011

When Will a Synthetic Biologist be called to St... -

September 24, 2011

Engineering Genetic Codes -

September 10, 2011

It's Raining Caterpillars! -

September 01, 2011

Remodeling Cells with RNA -

August 18, 2011

The Promises, Demands, and Risks of Garage Biology -

August 10, 2011

DIY Hardware for the Home Biology Lab -

August 03, 2011

Synthetic Biology at Home -

July 27, 2011

The Most Interesting Paper I've Ever Read -

July 20, 2011

DNA Synthesis -

July 13, 2011

High Throughput Sequencing and Cost Trends -

July 06, 2011

Sanger Sequencing -

June 29, 2011

Thinking Like Engineers -

June 23, 2011

Artemisinin: A Synthetic Biology Success Story -

June 14, 2011

Synthetic Biology in the Spotlight -

June 06, 2011

PCR: A Revolutionary Invention -

May 31, 2011

E. coli and Chassis -

May 23, 2011

Molecular Modeling -

May 16, 2011

Student Research -

May 09, 2011

Modeling and E. coli that Count -

May 02, 2011

DNA Origami -

April 25, 2011

The Repressilator -

April 18, 2011

Abstraction -

April 11, 2011

More on Operons -

April 03, 2011

Promoters

« Prev « Prev Next » Next »

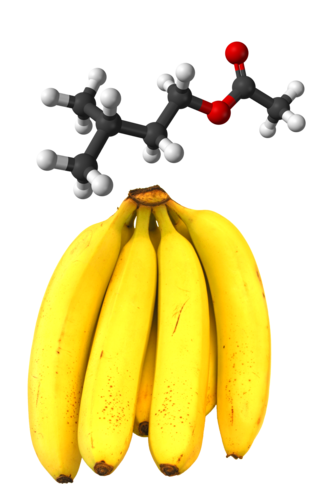

My last post described composite parts and gave a couple brief examples. Now I would like to talk in-depth about a cool example of composite parts: bacterial odor generators. When I say bacterial odor generators, I mean a system that produces an odorant compound not naturally produced by E. coli. After all, E. coli doesn't need to be programmed to smell like feces-it already does! This post is first and foremost a description of the Eau d'E. coli project done by Reshma Shetty and the 2006 MIT iGEM team. I hope you will enjoy this opportunity to learn about a real and interesting research project in this field.

My last post described composite parts and gave a couple brief examples. Now I would like to talk in-depth about a cool example of composite parts: bacterial odor generators. When I say bacterial odor generators, I mean a system that produces an odorant compound not naturally produced by E. coli. After all, E. coli doesn't need to be programmed to smell like feces-it already does! This post is first and foremost a description of the Eau d'E. coli project done by Reshma Shetty and the 2006 MIT iGEM team. I hope you will enjoy this opportunity to learn about a real and interesting research project in this field.