Abstract

The recessive T allele of the missense polymorphism rs709596309 C > T of the leptin receptor gene is associated with intramuscular fat. However, its overall impact on pork production is still partial. In this work, we investigated the all-round effects of the TT genotype on lean growth efficiency and carcass, meat and fat quality using data from an experiment that compared the performance of 48 TT and 48 C– (24 CT and 24 CC) Duroc barrows. The TT pigs were less efficient for lean growth than the C– pigs. Although heavier, their carcasses had less lean content, were shorter and had lighter loins. Apart from increasing marbling and saturated fatty acid content, changes caused by the TT genotype in meat and fat quality are likely not enough to be perceived by consumers. The effect on visual marbling score exceeded that on intramuscular fat content, which suggests a direct influence of the T allele on the pattern of fat distribution in muscle. With current low-protein diets, the T allele is expected to be cost-effective only in niche markets where a very high level of marbling is critical.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Leptin is a hormone secreted mainly by white adipocytes that regulates food intake and energy balance in mammals1. Although leptin deficiency leads to excessive food intake and increased body fat mass, obesity is mostly characterized not by leptin deficiency, but by hyperleptinemia. This is due to impaired leptin-mediated signaling that decreases tissue sensitivity to leptin2. Defective mutations in the leptin receptor gene (LEPR) are one of the causes for leptin resistance. In pigs, it has been shown that the homozygous for the recessive T allele of the missense polymorphism rs709596309 C > T of LEPR3 display higher levels of circulating leptin and fat deposition4,5, a clinical outcome that is compatible with a defective expression of the leptin receptor6.

The TT pigs not only deposit more subcutaneous and inner fat but also intramuscular fat (IMF), both in raw5 and dry-cured products7. It is generally accepted that IMF has a favorable effect on the sensory attributes of pork8,9, although its influence on acceptability depends on the consumer habits10,11,12 and the type of product. Thus, in pork products such as dry-cured ham, IMF content is closely connected to the consumers' preference13. Previous results have shown that TT pigs are heavier at weaning14 and at the end of fattening15 than C– (CC and CT) pigs. However, there is still limited experimental evidence on its impact on feed efficiency16,17. This poses a challenge to the use of this allele in pig breeding, as the potential benefits on meat quality need to be contrasted against the expected losses in lean growth efficiency and retail cut distribution. Therefore, the aim of this work was to investigate in a single experiment the effect of the LEPR rs709596309 C > T variant on lean growth efficiency during fattening and its relationship with carcass and meat quality traits.

Materials and methods

Experimental design and performance traits

The pigs used in this research were 96 barrows (48 TT and 48 C–, of which 24 were CT and 24 CC) from litters produced by 37 sows and 16 boars from the same Duroc line18. All pigs were previously genotyped for the LEPR rs709596309 C > T variant as described by Solé et al.17. At around 65 days of age (SD 2), pigs were delivered in one batch to the IRTA swine test station in Monells (Department of Climate Action, Food and Rural Agenda, Govern of Catalonia, Spain) for performance testing. There, the barrows were housed in 48 alternating pens of two pigs (1 m2/pig) with the same genotype (TT or C–) and reared under the same experimental conditions until 202 days (SD 2) of age. In order to mitigate potential maternal effects and competition at feeding, live body weight at the beginning of the test was equalized across genotypes (0.9 kg of difference) and within pen (0.3 kg of difference, on average). During the fattening period, all pigs had ad libitum access to commercial growing (until 90 days of age; 10.0 MJ/kg of net energy, 15.0% crude protein) and finishing (from 90 days of age to slaughter; 10.2 MJ/kg of net energy, 13.7% crude protein) diets (Table S1, Esporc, Riudarenes, Girona, Spain). At around 70 (69), 90 (92), 140 (142), 155 (155) and 200 (202) days of age, every pig was individually weighed and its backfat and loin thickness at 5 cm off the midline at the position of the last rib were measured using a portable ultrasonic scanner (Piglog 105; Frontmatec, Kolding, Denmark). Feed intake was recorded daily on a pen basis and summed up for each age interval. The average daily gain, feed intake and feed conversion ratio of the pen in each age interval were calculated thereafter. The residual feed intake of the pen was determined as the difference between the actual and the expected feed intake, which was estimated as the feed intake adjusted for the average metabolic body weight during the period plus the body weight and backfat thickness gain throughout the period19. The coefficient of determination for feed intake regression models ranged from 0.66 (from 140 to 155 days of age) to 0.80 (from 155 to 200 days of age).

Carcass quality traits

All pigs were slaughtered in the same abattoir at 203 days of age (SD 2), where carcass weight was recorded, and carcass backfat and loin thickness were ultrasonically predicted with an automatic carcass grading equipment (AutoFOM, SFK-Technology, Denmark) at 6 cm off the midline between the third and fourth last ribs. The dressing percentage was calculated as the ratio of carcass weight and live body weight at 200 days while the carcass lean percentage was estimated in accordance with the prediction equation approved for Spain (Decision 2012/384/UE). After chilling at 2 °C for approximately 24 h, two additional measurements of carcass backfat thickness were directly taken using a ruler. The first was obtained at the level of the last rib, in the same location as the in vivo measurements, whereas the second one was recorded at the level of the gluteus medius muscle. Carcass length was measured from the anterior edge of the symphysis pubic to the recess of the first rib. Then, each carcass was divided into primary cuts and the hams, and the loin were individually weighted. Immediately after quartering, a section of around 250 g from the middle part of the longissimus muscle (LM) and from the gluteus medius muscle (GM), including subcutaneous fat, were taken. Both samples were individually vacuum-packed and transported during the same day to the laboratory.

Cured ham processing

Left hams were individually traced and dry-cured through a four-step process7. First, hams were covered with salt and kept for 10 to 14 days at 2 ºC. Then, they were dried for 3 months following a slow ramp of increasing temperatures (from 3 to 10 ºC). After that, the hams were ripened for 6 months at 9 to 14 ºC. Finally, in the last ripening step, they were allocated into a single seasoning batch and kept in room temperature (15 to 20 ºC) for 16 months until around one third of the initial weight was lost. At the end of this process, the final weight of the bone-in cured ham and the weight loss during the whole dry-curing process were recorded. A slice from the middle of the ham including the biceps femoris (BF) and the semitendinosus (ST) muscles was taken, individually vacuum-packaged and then transported to the laboratory for further determinations.

Meat and fat quality traits

Once in the laboratory, each LM and GM sample was split into two parts. One of the subsamples was used for immediate analysis while the other was stored in deep freeze until required. With the first subsample, pH and color readings were made on the exposed surface of LM and GM as well as color readings of the gluteal subcutaneous fat7. The pH was measured with a portable pH-meter (pH 7 Vio, XS-Instruments, Carpi, Italy) and color space coordinates20 for lightness (L*), redness (a*) and yellowness (b*) with a spectrophotometer (CM-700d, Konica Minolta Sensing Inc., Osaka, Japan). For each color coordinate, the final value was the average of six measurements taken in triplicate at two muscle sites. The Hue angle (h* = arctan(b*/a*), expressed in degrees; from dark to white) and chroma (C* = (a*2 + b*2)0.5; from dull to vivid intensity) variables were calculated. Moreover, a zenithal photograph of the exposed surface of LM was taken at 30 cm using a 12-megapixel camera with a wide-angle lens. Each photo was graded for marbling by 12 meat industry experts and 48 non-expert consumers according to the marbling standards of the National Pork Producers Council, USA (1: not at all, to 10: very much), and the result compared with the abattoir internal score for fat infiltration (from 1: little marbling, to 5: very much marbling), which was taken on the same surface of the raw LM by a technician of the cutting room at the moment of sampling. At least 20 g of each muscle was used to determine dry matter in duplicate by drying 24 h at 102 ºC in an air oven.

The second subsample was used for fat analysis. Defrosted muscle samples were trimmed of subcutaneous and intermuscular fat, freeze-dried and pulverized. Then, IMF content and fatty acid composition in LM and GM as well as fatty acid composition of the gluteal subcutaneous fat were determined in duplicate by quantitative determination of the individual fatty acids by gas chromatography21. The proportion of saturated fatty acids (SFA: C14:0, C16:0, C18:0, and C20:0); monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA: C16:1n-9, C18:1n-7, C18:1n-9, and C20:1n-9); and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA; 18:2n-6, C18:3n-3, C20:2n-6, and C20:4n-6) were expressed as percentages relative to total fatty acid content. The IMF content was calculated as the sum of each individual fatty acid expressed as triglyceride equivalents on a dry tissue basis22.

Cured ham and fat quality traits

Dry-cured ham slices were placed on a polystyrene white tray. Color measurements were made directly on the exposed surface of BF and ST. Then, BF and ST muscles were dissected out from the ham slice and minced. Around 4 g of each muscle was used to determine dry matter while the rest of the sample was stored at − 20 ºC, freeze-dried and pulverized for fatty acid analysis. Color, dry matter and fatty acid composition were determined following the same procedures described above for raw LM and GM. Also, identically to LM and GM, a zenithal photograph of the exposed surface of the slice was taken. A panel of 16 consumers graded each slice for marbling according to the standards of the National Pork Producers Council, USA.

Gene expression analysis

Differential gene expression of LEPR genotypes was analyzed using RNA‑seq data of 38 pigs (12 TT, 17 CT, and 9 CC) of the same Duroc line23. Total RNA was isolated from semimembranosus muscle samples using TRI Reagent (Invitrogen, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and Direct-zol™ RNA Miniprep Plus Kit (Zymo Research, BioSystems, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA samples were sequenced by Centre Nacional d’Anàlisi Genòmica (CNAG-CRG, Barcelona, Spain, http://www.cnag.crg.eu/). Libraries were prepared using the TruSeq SBS v-3HS kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Each library was paired-end sequenced (2 × 100 bp) to 65 M reads with phred quality score 80–90% in a Hi-Seq 2000 platform. After the alignment with Sus scrofa reference genome (Sscrofa11.1), reads for each LEPR genotype were counted with the Feature Counts v1.24.1 software24.

Statistical analyses

The effect of the LEPR genotype (TT and C–) on gene expression was estimated using a model that included the LEPR genotype of the individual as systematic effect. For individual performance, carcass and quality traits, the model also included the LEPR genotype of the dam (TT and C–) as systematic effect and the pig polygenic effect. In addition, age at measurement (for performance traits), carcass weight (for carcass and quality traits), and IMF (for fatty acid content) were added as covariates. In matrix notation, the model was y = Xb + Za + e, where y is the vector of observations for a trait; b, a and e are the vectors of systematic (pig and sow LEPR genotype and the corresponding covariate), polygenic and residual effects, respectively; and X and Z are the incidence matrices that relate b and a with y, respectively. Inferences were done in a Bayesian setting using the TM software25. The traits were assumed to be conditionally normally distributed as [y | b, a, Iσe2] ~ N (Xb + Za, Iσe2), where σe2 is the residual variance and I the appropriate identity matrix. The pig effects conditional on the additive genetic variance σa2 were assumed multivariate normally distributed with mean zero and variance Aσa2, where A was the numerator relationship matrix calculated from a two-generation pedigree. For feeding traits, records were taken on a pen basis, so the observations were the average of the two pigs in the pen. Accordingly, the pig polygenic effect was dropped from the model and the average age at measurement of the two pigs in the pen was used as a covariate. Marginal posterior distributions for all unknowns were estimated using Gibbs sampling26. Statistical inferences (namely, posterior means and SD, posterior probabilities of differences being greater or lower than 0 [P0], and the highest posterior density region at 95% [HPD95]) were derived from the samples of the marginal posterior distribution using a unique chain of 1,000,000 iterations, where the first 200,000 were discarded and 1 sample out of 1000 iterations was retained. In particular, the effect of the LEPR genotype was estimated as the mean of the marginal posterior distribution of the difference between genotypes. Convergence was tested using the Z-criterion of Geweke and visual inspection of convergence plots. We considered that there was very strong, strong or moderate evidence of difference between genotypes when P0 was at least 0.99, 0.95 or 0.90, respectively.

Ethical approval

Pigs used in the study were raised and slaughtered following applicable regulations and good practice guidelines on the protection of animals kept for farming purposes, during transport and slaughter. In accordance with European Directive 2010/63/EU and Spanish Royal Decree 53/2013, no invasive procedures or treatments were performed on the animals in this study. The experimental protocol was reviewed by the Ethical Committee on Animal Experimentation of the University of Lleida (CEEA 04-06/21).

Results

Gene expression

Gene expression analysis was performed in the semimembranosus muscle, since it was not possible to obtain GM and LM samples immediately after slaughter. Leptin receptor and leptin gene expression in the semimembranosus muscle of the three LEPR genotypes is given in Fig. 1. As expected, the relative expression of LEPR was 2.8-fold higher (P0 > 0.99) in C– pigs than in TT pigs. In contrast, the relative expression of leptin was 3.8-fold higher (P0 > 0.99) in TT pigs as compared to C– pigs. The CC pigs had 1.5-fold higher (P0 = 0.98) expression of LEPR than CT pigs, but no difference was detected between them for leptin expression.

Average reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM) of (A) leptin receptor (LEPR) and (B) leptin (LEP) transcripts by LEPR genotype (TT, CT and CC).. Within transcript, means with different letters differ (P0 > 0.95). P0: Posterior probability of the difference between genotypes being greater (if positive) or lower (if negative) than zero. Leptin receptor expression was different between LEPR genotypes (P0 > 0.99, between TT and CT, and P0 = 0.98, between CT and CC) while leptin expression differed between TT and CT (P0 > 0.99), but not between CT and CC (P0 = 0.50).

Performance traits

On average, TT pigs were heavier and fatter than C– pigs throughout fattening (Table 1), with the maximum difference reached at the end of the period, from 155 to 200 days of age (+ 4.9 kg, P0 = 0.95, for live weight, and + 2.4 mm, P0 = 0.99, for backfat thickness). The negative effect of TT on loin thickness was not so evident (− 1.2 mm, P0 = 0.88, at the end of fattening). Although fatter, the TT pigs were able to grow faster during fattening (+ 36 g/d, P0 = 0.94). As shown in Table 2, the increased growth rate of the TT pigs was accompanied by an even larger increase of feed intake (+ 227 g/d, P0 > 0.99). As a result, the TT pigs had a higher feed conversion ratio during fattening than C– pigs (+ 124 g/kg, P0 > 0.99). However, from 155 to 200 days, feed conversion ratio was similar between both genotypes (− 12 g/kg, for TT, P0 = 0.52), with feed intake (+ 342 g/d, P0 > 0.99) more aligned with weight gain (+ 75 g/d, P0 = 0.93) between genotypes. The difference between genotypes became much lower and less evident for the residual feed intake (+ 45 g/d, P0 = 0.87, from 75 to 200 days), a result that indicates that around 80% of the excess feed consumed by the TT pigs can be attributed to differences in the level of production (i.e. size and body weight and fat gain).

Carcass quality traits

The differences between the TT and C– pigs for carcass traits are given in Table 3. The TT pigs presented a lower dressing percentage (− 0.6%, P0 = 0.91) and, in line with on-live measurements, their carcasses were heavier (+ 4.1 kg, P0 > 0.99) but fatter (− 3.8% of lean percentage, P0 > 0.99). Moreover, the carcasses of the TT pigs were shorter (− 1.1 cm, P0 = 0.96) and had thinner (− 4.6 mm, P0 > 0.99) and lighter (− 0.3 kg, P0 > 0.99) loins. No sufficient evidence was found to support that the weight of hams was lighter in TT pigs (− 0.2 kg, P0 = 0.76). Once adjusted for carcass weight, the weight of the dry-cured ham of TT pigs (− 0.0 kg, P0 = 0.53) and the weight loss during the dry-curing process (− 0.3 kg, P0 = 0.69) also did not differ between genotypes.

Muscle quality traits

The LEPR genotype had little influence on muscle color and pH (Tables 4 and 5). Taking the results of raw LM and GM as a whole, they indicate that the TT genotype had a positive impact on L* (+ 1.8, P0 = 0.93, in GM) and pH (+ 0.1, P0 = 0.98, in LM), while negative on a* (− 0.6, P0 = 0.96, in GM). Although similar in magnitude, the TT genotype increased a* in cured ST (+ 0.6, P0 = 0.95) and b* in cured BF (+ 0.8, P0 = 0.93). The effect of the TT genotype on IMF was more evident in the cured (+ 1.3%, P0 > 0.99, in BF) than in the raw muscles, where it was only moderately evident in GM (+ 0.8%, P0 = 0.91). In contrast, both industry experts and consumers were able to detect a clear effect of the TT genotype on fat infiltration (+ 0.5, P0 > 0.99) and marbling, both in raw loin (+ 0.8, P0 = 0.99, and + 0.6, P0 = 0.96, for experts and consumers, respectively) and in dry-cured ham (+ 1.2, P0 > 0.99). There was a positive correlation of IMF in LM with visual fat infiltration (0.53, P0 > 0.99) and marbling (0.64 and 0.63, P0 > 0.99, for experts and consumers, respectively) and between fat infiltration and marbling (0.56 and 0.55, P0 > 0.99, for experts and consumers, respectively). The correlation of marbling in dry-cured ham with IMF was also positive but higher than in loin (0.80 and 0.76, P0 > 0.99, for BF and ST, respectively).

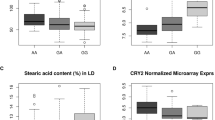

Fat quality traits

The fatty acid composition of IMF in LM and GM is shown in Table 6 and of IMF in BF and ST in Table 7. The IMF of the TT pigs presented higher SFA in all muscles, either raw (+ 1.0% and + 1.3%, for LM and GM, respectively, P0 > 0.99) or cured (+ 0.6%, P0 = 0.98, for BF, and + 0.7%, P0 = 0.97. for ST). The increase in SFA was mostly at the expense of PUFA (− 0.9% and − 1.1%, P0 > 0.99, for LM and GM, respectively, and − 0.4%, P0 = 0.97, for BF), excepting for ST, where MUFA was the one that decreased in favor of SFA (− 0.7%, P0 = 0.99). In fact, the MUFA content was relatively stable for LM, (− 0.2%, P0 = 0.70), GM (− 0.2%, P0 = 0.82) and BF (− 0.3%, P0 = 0.80), but not for ST (− 0.7%, P0 = 0.99). This was because, unlike in other muscles, C18:1n-9 in ST experienced a considerable decrease in TT pigs (− 0.5%, P0 = 0.97). As in muscle, the LEPR genotype had a minor influence on subcutaneous fat color (Table S2), which also revealed a more saturated fatty acid composition (Table S3). Thus, the subcutaneous fat of the TT pigs had greater L* (+ 0.8, P0 = 0.98) and lower a* (− 0.3, P0 = 0.99) and b* (− 0.9, P0 > 0.99). The main change in the subcutaneous fatty composition caused by the TT genotype was a substitution of SFA for MUFA (+ 0.6%, P0 = 0.99), which was mainly due to a decrease in C18:1n-9 (− 0.7%, P0 = 0.98).

Discussion

This study reports the results from an experiment designed to investigate the effects of the LEPR rs709596309 C > T variant on lean growth efficiency and carcass, meat and fat quality traits in pigs. Although other variants have been reported in the LEPR gene3,14,27,28,29, this is the one that presents the most consistent results across studies. The T allele involves the amino acid change L663F in the coded protein3 that reduces leptin receptor functionality6. Leptin is produced by adipocytes and acts as an anorexigenic signal in hypothalamic neurons, so loss of leptin signaling causes hyperphagia and decreased energy expenditure30. Óvilo et al.6 found that TT pigs had a third of LEPR hypothalamic expression compared to CC pigs, with CT pigs showing intermediate values. The reduced expression of LEPR in the hypothalamus of the pigs carrying the T allele is in line with the results found here in muscle, thus contributing to support causality and the paracrine role of leptin receptors in maintaining local tissue homeostasis31,32. As expected in the leptin-resistance obesity model, the deficit in LEPR expression was counteracted by increased leptin expression. However, this compensatory effect occurred in TT pigs, but not in CT pigs, suggesting that leptin resistance only appears when a minimum threshold of LEPR is not reached, a hypothesis that, in turn, would explain the recessive behavior of the T allele.

Pigs used here were from a Duroc line that produces for premium markets. Unlike lines used as terminal sires of 3-way crosses33,34, the Duroc lines used as purebred or 2-way Duroc crossbreds have been selected less aggressively for lean growth to keep IMF at required levels35, such as those needed to produce dry-cured ham, where IMF is highly appreciated36. Therefore, alleles associated with fatness, such as the T allele, are more likely to be present in traditional Duroc lines4,5 and in local breeds. For instance, the T allele is almost fixed in Iberian and related breeds14,37.

We previously demonstrated that TT sows provide a negative maternal environment to piglets that reduces their weight at weaning15, which is counteracted by a positive direct effect of the TT genotype on the weight and vitality of the piglets at birth as well as on growth during lactation14. As a continuation of this research, in the present study we further pursued on the effect of the TT genotype on performance traits during the growing-fattening period. Our findings showed that TT pigs were heavier than C– pigs at slaughter, corroborating prior results in this Duroc line using on-farm data17 and from two backcrosses involving Iberian, Duroc and Landrace pigs6. The TT pigs also had higher feed intake throughout fattening, but it was only during the finishing period (155 to 200 days) that increased feed intake had a correlative response in growth rate. In controlled research settings, with high energy-dense diets and low stocking densities, such as this one, feed intake should be close to or just at the maximum potential for voluntary energy intake. At this point, pigs are no longer in an energy-dependent state of growth38. Results indicate that TT pigs have a greater capacity for energy intake and so for growth, which is consistent with a thrifty behavior17. On the other hand, as long as reduced protein diets affect growth performance39, then, conversely, leaner C– pigs should be more prone to further decline in growth.

The TT pigs grew faster but had a poorer feed conversion ratio. The difference between genotypes for feed conversion decreased with age until vanishing in the finishing period. In terms of weight gain, the TT pigs are less efficient at younger ages because they initiate fat mass expansion earlier, but, with time, the fat-to-lean deposition ratio becomes more balanced across genotypes and so also the feed conversion ratio. This trend is likely to be more pronounced here, since our pigs were barrows, which are known to start to deposit fat earlier and are fatter than entire males40. Feed efficiency, however, did not differ between genotypes when it was measured in terms of residual feed intake, i.e. if also fat accretion is considered. Thus, in global terms, TT pigs are not intrinsically worse feed converters than C– pigs, but rather metabolically different, in the sense that their dietary intake is directed more towards lipid than protein accumulation to optimize energy savings. In this way, despite being heavier, TT carcasses had less lean mass (− 4.7 kg, P0 > 0.99, and − 3.8 kg, P0 > 0.99, unadjusted and adjusted for carcass weight, respectively, and calculated as the product of carcass weight and lean percentage). The storage of excess fat in TT pigs decreased dressing percentage and carcass quality and led to a lighter loin than C– pigs. Each carcass was divided into standardized commercial cuts according to customary procedure used in Spanish abattoirs. We were able to individually track untrimmed hams (whole leg) and loin, but not other economically relevant cuts, which were weighted collectively by LEPR genotype. In accordance with the observed trends for individual results, TT pigs, as compared with C– pigs, showed a lower proportion of hams (25.0% vs 25.8%), loin (5.4% vs 5.7%), shoulder (whole leg, 14.7% vs 15.2%) and neck filet (4.8% vs 5.0%) in the carcass, while higher proportion of belly (9.8% vs. 8.8%), as expected for a fatty cut41.

Increased fatness in TT carcasses was not accompanied by a marked positive response in IMF, as we have previously observed throughout fattening42 and at slaughter5, and as could be anticipated by the positive correlation of IMF with backfat thickness in this Duroc line43, including the one found here (+ 0.29, P0 = 0.99). Although IMF tended to be higher in TT pigs, we were only able to detect this effect in cured BF, the least fatty among the four investigated muscles, where therefore differential leptin sensitivity between LEPR genotypes is expected to be more acute. Several hormones, including leptin, regulate fatty acid metabolism in skeletal muscle44,45. Leptin reduces intramuscular triglycerides by increasing fatty acid oxidation and triglyceride hydrolysis while reducing fatty acid esterification. Leptin resistance downregulate these processes in skeletal muscle of obese individuals46 and can be differentially expressed depending on gender47 and muscle48. Our experimental pigs achieved an extreme level of IMF compared to present-day standards, showing twice as much IMF as their commercial counterparts49, so we can surmise that, except for BF, they were at a stage in which adipocyte hypertrophy was close to a plateau. In addition to effective response to selective breeding35, this elevated IMF level is explained by research experimental conditions, including the diet. Current diets are at least 3% lower in protein than previous ones5 and reduced protein diets increase IMF39,50. This, in combination with high nutrient intake during growth, could have increased the number and size of adipocytes in skeletal muscle51,52 and blurred the effect of LEPR on IMF, particularly in LM, GM and ST. Leptin gene expression differs across adipose depots, marking especially subcutaneous fat53. Intramuscular adipocytes are less metabolically active and less sensible to leptin as compared with subcutaneous and perirenal adipocytes. Findings in pigs would confirm this to the extent that circulating leptin is more correlated with backfat thickness and intermuscular fat than with IMF54.

In contrast to IMF, the TT pigs evidenced a higher level of visible fat than C– pigs, both in loin and dry-cured ham. Fat infiltration and marbling scores are two correlated measures of visible fat. Fat perception depends on IMF but also on how it is distributed over the exposed surface of the muscle. The correlation of IMF in LM with fat infiltration and marbling was positive but moderate, thereby suggesting that, in the TT loins, IMF was displayed in a more striking appearance, probably because it is assembled according to a more perceptible density distribution. Human subjectivity and fatty acid composition can lead to misreading fat. Since SFA have higher melting points, at room temperature fat with more SFA becomes more visible. These potential perturbations did not neutralize the positive effect of the TT genotype on fat infiltration and marbling, which was maintained when extreme ratings were discarded or after adjusting the scores for IMF, SFA or PUFA. Marbling is a key cue of visual appearance and visual appearance is highly related with consumers' expectations of meat quality. Although some marbling is generally appreciated, a feeling of excess fat, coupled with increased SFA, can be counterproductive and may deter more diet- and health-conscious consumers from choosing TT pork at the point of purchase.

Besides IMF and visual appearance, pH, color, and fatty acid composition are the other main sources of sensory differentiation in pork55,56,57. The most remarkable effect of LEPR on these traits was on fatty acid composition, particularly increasing SFA. It is known that SFA increases with fat content, both in IMF and subcutaneous fat58. However, TT pigs showed a greater proportion of SFA even adjusting for IMF or backfat thickness, which confirms that the endogenous synthesis of fat begins earlier in TT pigs than in C– pigs. Increased SFA is achieved at the expense of PUFA or MUFA, depending on the amount of adipose tissue. In general, SFA replace PUFA when the fat content is lower (i.e. in LM, GM, and BF) or MUFA when the fat content is higher (i.e. in ST and subcutaneous fat). Given that there were only minor differences between genotypes for pH and moisture, the positive effect of the TT genotype on L* (and negative on a*) should be attributed to increased visual fat and SFA content59. Previous studies have reported that IMF increases lightness60 and decreases the presence of pigments such as myoglobin61. The effects on color were more evident in subcutaneous fat, where b* was also affected. Unlike dry-cured ham7, raw subcutaneous fat of TT pigs was less yellow, which is consistent with the fact that yellowness is associated with lower solid fat content and with processing time62.

Conclusions

This study provides further evidence that leptin plays an important role in the regulation of feed intake and development of adiposity. Findings here demonstrate that the TT pigs are less efficient at producing pork and have worse carcass quality. Apart from increasing marbling, changes in meat quality caused by the TT genotype are minor and likely not enough to be perceived by consumers. The effect on visual marbling exceeds IMF, which argues for a specific effect of LEPR on the IMF distribution pattern. At least in fat pigs fed low-protein diets, the benefits of the T allele are, at best, limited to satisfying niche markets aimed at consumers who are willing to pay for a high level of marbling. On the contrary, the T allele provides a convenient model for research into dietary intake, metabolism and adiposity.

Data availability

The data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- a*:

-

Color space coordinate for redness

- b*:

-

Color space coordinate for yellowness

- BF:

-

Biceps femoris muscle

- GM:

-

Gluteus muscle

- HPD95:

-

Highest posterior density interval at 95% of probability

- IMF:

-

Intramuscular fat

- L*:

-

Color space coordinate for lightness

- LEPR :

-

Leptin receptor gene

- LM:

-

Longissimus muscle

- MUFA:

-

Monounsaturated fatty acids

- P0 :

-

Posterior probability of a difference being greater or lower than 0

- PUFA:

-

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- ST:

-

Semitendinosus muscle

- SFA:

-

Saturated fatty acids

References

Houseknecht, K. L., Baile, C. A., Matteri, R. L. & Spurlock, M. E. The biology of leptin: A review. J. Anim. Sci. 76(5), 1405–1420. https://doi.org/10.2527/1998.7651405x (1998).

Mazor, R. et al. Cleavage of the leptin receptor by matrix metalloproteinase-2 promotes leptin resistance and obesity in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 10(455), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aah6324 (2018).

Óvilo, C. et al. Fine mapping of porcine chromosome 6 QTL and LEPR effects on body composition in multiple generations of an Iberian by Landrace intercross. Genet. Res. 85(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016672305007330 (2005).

Uemoto, Y. et al. Effects of porcine leptin receptor gene polymorphisms on backfat thickness, fat area ratios by image analysis, and serum leptin concentrations in a Duroc purebred population. Anim. Sci. J. 83(5), 375–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-0929.2011.00963.x (2012).

Ros-Freixedes, R. et al. Genome-wide association study singles out SCD and LEPR as the two main loci influencing intramuscular fat content and fatty acid composition in duroc pigs. PLoS One 11(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152496 (2016).

Óvilo, C. et al. Hypothalamic expression of porcine leptin receptor (LEPR), neuropeptide y (NPY), and cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) genes is influenced by LEPR genotype. Mamm. Genome 21(11–12), 583–591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00335-010-9307-1 (2010).

Suárez-Mesa, R. et al. Leptin receptor and fatty acid desaturase-2 gene variants affect fat, color and production profile of dry-cured hams. Meat Sci. 173, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2020.108399 (2021).

Ruiz-Carrascal, J., Ventanas, J., Cava, R., Andrés, A. I. & García, C. Texture and appearance of dry cured ham as affected by fat content and fatty acid composition. Food Res. Int. 33(2), 91–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0963-9969(99)00153-2 (2000).

Lonergan, S. M. et al. Influence of lipid content on pork sensory quality within pH classification. J. Anim. Sci. 85(4), 1074–1079. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2006-413 (2007).

Duong, C., Sung, B., Lee, S. & Easton, J. Assessing Australian consumer preferences for fresh pork meat attributes: A best-worst approach on 46 attributes. Meat Sci. 193, 108954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2022.108954 (2022).

Font-i-Furnols, M., Tous, N., Esteve-Garcia, E. & Gispert, M. Do all the consumers accept marbling in the same way? The relationship between eating and visual acceptability of pork with different intramuscular fat content. Meat Sci. 91(4), 448–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.02.030 (2012).

Ngapo, T. M. Consumer preferences for pork chops in five Canadian provinces. Meat Sci. 129, 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2017.02.022 (2017).

Font-i-Furnols, M. & Guerrero, L. Consumer preference, behavior and perception about meat and meat products: An overview. Meat Sci. 98(3), 361–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2014.06.025 (2014).

Suárez-Mesa, R. et al. The leptin receptor gene affects piglet behavior and growth. J. Anim. Sci. 101, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/skad29610.1093/jas/skad296 (2023).

Solé, E. et al. The effect of the SCD genotype on litter size and weight at weaning. Livest. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2021.104763 (2021).

Pérez-Montarelo, D. et al. Joint effects of porcine leptin and leptin receptor polymorphisms on productivity and quality traits. Anim. Genet. 43(6), 805–809. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2052.2012.02338.x (2012).

Solé, E. et al. Antagonistic maternal and direct effects of the leptin receptor gene on body weight in pigs. PLoS One 16, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246198 (2021).

Solanes, F. X., Reixach, J., Tor, M., Tibau, J. & Estany, J. Genetic correlations and expected response for intramuscular fat content in a Duroc pig line. Livest. Sci. 123(1), 63–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2008.10.006 (2009).

Herd, R. M. & Arthur, P. F. Physiological basis for residual feed intake. J. Anim. Sci. 87(14 Suppl), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2008-1345 (2009).

Commission Internationale de l’Éclairage CIE. Colorimetry, Publication CIE No. 15.2. 2nd ed. (1886).

Bosch, L., Tor, M., Reixach, J. & Estany, J. Estimating intramuscular fat content and fatty acid composition in live and post-mortem samples in pigs. Meat Sci. 82(4), 432–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2009.02.013 (2009).

AOAC. Official method 960.39 fat (crude) or ether extract in meat. In International A (eds) Official Methods of Analysis [Internet], 17th ed., pp 2 (Association of Official Agricultural Chemists, 2000). http://www.eoma.aoac.org/methods/info.asp?ID=16128.

Solé, E. et al. Transcriptome shifts triggered by vitamin A and SCD genotype interaction in Duroc pigs. BMC Genom. 23(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-021-08244-3 (2022).

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. FeatureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30(7), 923–930. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656 (2014).

Legarra, A,, Varona, L,, López, E. TM threshold model. http://snp.toulouse.inra.fr/~alegarra/manualtm.pdf (Accessed 11 October 2023) (2008).

Gelfand, E. & Smith, A. Sampling-based approaches to calculating marginal densities. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 85(410), 398–409. https://doi.org/10.2307/2289776 (1990).

Muñoz, G. et al. Single-And joint-population analyses of two experimental pig crosses to confirm quantitative trait loci on Sus scrofa chromosome 6 and leptin receptor effects on fatness and growth traits. J. Anim. Sci. 87(2), 459–468. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2008-1127 (2009).

Zhang, C. Y. et al. Associations between single nucleotide polymorphisms in 33 candidate genes and meat quality traits in commercial pigs. Anim. Genet. 45(4), 508–516. https://doi.org/10.1111/age.12155 (2014).

Chen, C. C., Chang, T. & Su, H. Y. Characterization of porcine leptin receptor polymorphisms and their association with reproduction and production traits. Anim. Biotechnol. 15(1), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1081/ABIO-120037903 (2004).

Van De Wall, E. et al. Collective and individual functions of leptin receptor modulated neurons controlling metabolism and ingestion. Endocrinology 149(4), 1773–1785. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2007-1132 (2008).

Guerra, B. et al. Leptin receptors in human skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 102(5), 1786–1792. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.01313.2006 (2007).

Perez-Suarez, I. et al. Severe energy deficit upregulates leptin receptors, leptin signaling, and PTP1B in human skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 123(5), 1276–1287. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00454.2017 (2017).

Blasco, A. et al. Comparison of five types of pig crosses. I. Growth and carcass traits. Livest. Prod. Sci. 40(2), 171–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-6226(94)90046-9 (1994).

Edwards, S. A., Wood, J. D., Moncrieff, C. B. & Porter, S. J. Comparison of the Duroc and large white as terminal sire breeds and their effect on pigmeat quality. Anim. Prod. 54(2), 289–297. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003356100036928 (2010).

Estany, J., Ros-Freixedes, R., Tor, M. & Pena, R. N. Triennial growth and development symposium: Genetics and breeding for intramuscular fat and oleic acid content in pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 95(5), 2261–2271. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas2016.1108 (2017).

Carrapiso, A. I. & García, C. Effect of the Iberian pig line on dry-cured ham characteristics. Meat Sci. 80(2), 529–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2008.02.004 (2008).

Muñoz, M. et al. Diversity across major and candidate genes in European local pig breeds. PLoS One 13(11), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207475 (2018).

De La Llata, M. et al. Effects of dietary fat on growth performance and carcass characteristics of growing-finishing pigs reared in a commercial environment. J. Anim. Sci. 79(10), 2643–2650. https://doi.org/10.2527/2001.79102643x (2001).

Kerr, B. J., McKeith, F. K. & Easter, R. A. Effect on performance and carcass characteristics of nursery to finisher pigs fed reduced crude protein, amino acid-supplemented diets. J. Anim. Sci. 73(2), 433–440. https://doi.org/10.2527/1995.732433x (1995).

Millet, S., Gielkens, K., De Brabander, D. & Janssens, G. P. J. Considerations on the performance of immunocastrated male pigs. Animal 5(7), 1119–1123. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731111000140 (2011).

Galve, A. et al. The effects of leptin receptor (LEPR) and melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) polymorphisms on fat content, fat distribution and fat composition in a Duroc×Landrace/Large White cross. Livest. Sci. 145(1–3), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2012.01.010 (2012).

Henriquez-Rodriguez, E., Bosch, L., Tor, M., Pena, R. N. & Estany, J. The effect of SCD and LEPR genetic polymorphisms on fat content and composition is maintained throughout fattening in Duroc pigs. Meat Sci. 121, 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2016.05.012 (2016).

Ros-Freixedes, R., Reixach, J., Bosch, L., Tor, M. & Estany, J. Genetic correlations of intramuscular fat content and fatty acid composition among muscles and with subcutaneous fat in Duroc pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 92(12), 5417–5425. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2014-8202 (2014).

Muoio, D. M., Dohn, G. L., Fiedorek, F. T., Tapscott, E. B. & Coleman, R. A. Leptiit directly alters lipid partitioning in skeletal muscle. Diabetes 46, 1360–1363. https://doi.org/10.2337/diab.46.8.1360 (1997).

Steinberg, G. R., Bonen, A. & Dyck, D. J. Fatty acid oxidation and triacylglycerol hydrolysis are enhanced after chronic leptin treatment in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 282, 593–600. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00303.2001 (2002).

Steinberg, G., Parolin, M., Heigenhauser, G. & Dyck, D. Leptin increases FA oxidation in lean but not obese human skeletal muscle: Evidence of peripheral leptin resistance. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 283, 187–192. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00542.2001 (2002).

Guerra, B. et al. Gender dimorphism in skeletal muscle leptin receptors, serum leptin and insulin sensitivity. PLoS One 3(10), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0003466 (2008).

Fuentes, T. et al. Leptin receptor 170 kDa (OB-R170) protein expression is reduced in obese human skeletal muscle: A potential mechanism of leptin resistance. Exp. Physiol. 95(1), 160–171. https://doi.org/10.1113/expphysiol.2009.049270 (2010).

Solé, E., Ros-Freixedes, R., Tor, M., Pena, R. N. & Estany, J. A sequence variant in the diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 2 gene influences palmitoleic acid content in pig muscle. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94235-z (2021).

Jiang, S. et al. Low-protein diets supplemented with glycine improves pig growth performance and meat quality: An untargeted metabolomic analysis. Front. Vet. Sci. 10, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2023.1170573 (2023).

Allen, C. E. Cellularity of adipose tissue in meat animals. Fed. Proc. 35, 2302–7 (1976).

Du, M., Wang, B., Fu, X., Yang, Q. & Zhu, M. J. Fetal programming in meat production. Meat Sci. 109, 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2015.04.010 (2015).

Hausman, G. J., Basu, U., Du, M., Fernyhough-Culver, M. & Dodson, M. V. Intermuscular and intramuscular adipose tissues: Bad vs. good adipose tissues. Adipocyte 3(4), 242–55. https://doi.org/10.4161/adip.28546 (2014).

Suzuki, K., Inomata, K., Katoh, K., Kadowaki, H. & Shibata, T. Genetic correlations among carcass cross-sectional fat area ratios, production traits, intramuscular fat, and serum leptin concentration in Duroc pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 87(7), 2209–2215. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2008-0866 (2009).

Gagaoua, M., Suman, S. P., Purslow, P. P. & Lebret, B. The color of fresh pork: Consumers expectations, underlying farm-to-fork factors, myoglobin chemistry and contribution of proteomics to decipher the biochemical mechanisms. Meat Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2023.109340 (2023).

Norman, J. L., Berg, E. P., Heymann, H. & Lorenzen, C. L. Pork loin color relative to sensory and instrumental tenderness and consumer acceptance. Meat Sci. 65(2), 927–933. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0309-1740(02)00310-8 (2003).

Cameron, N. D. et al. Genotype with nutrition interaction on fatty acid composition of intramuscular fat and the relationship with flavour of pig meat. Meat Sci. 55(2), 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0309-1740(99)00142-4 (2000).

Bosch, L., Tor, M., Reixach, J. & Estany, J. Age-related changes in intramuscular and subcutaneous fat content and fatty acid composition in growing pigs using longitudinal data. Meat Sci. 91(3), 358–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.02.019 (2012).

Moeller, S. J. et al. Consumer perceptions of pork eating quality as affected by pork quality attributes and end-point cooked temperature. Meat Sci. 84(1), 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2009.06.023 (2010).

Nollet, L. M. L. & Toldrá, F. Sensory analysis of foods of animal origin. In Sensory Analysis of Foods of Animal Origin 1st edn (eds Nollet, L. M. L. & Toldra, F.) 1–434 (CRC Press, 2010). https://doi.org/10.1201/b10822.

Lindahl, G., Lundström, K. & Tornberg, E. Contribution of pigment content, myoglobin forms and internal reflectance to the colour of pork loin and ham from pure breed pigs. Meat Sci. 59(2), 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0309-1740(01)00064-X (2001).

Gandemer, G. Lipids in muscles and adipose tissues, changes during processing and sensory properties of meat products. Meat Sci. 62, 309–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0309-1740(02)00128-6 (2002).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the personnel of Selección Batallé and the technicians at the Animal Breeding and Genetics Laboratory, Universitat de Lleida, for assistance with sampling and laboratory analyses. Eduard Molinero is gratefully acknowledged for his support with RNA-seq data.

Funding

This research is part of the Grant PID2021-125689OB-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/https://doi.org/10.13039/501100011033 and by “ERDF A way of making Europe”, by the “European Union.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JE and JR conceived and designed the experiment; RSM, JR, JE and RNP performed the experiment; RSM, RRF and JE performed data curation and analysis; JE and RRF acquired funding; RSM and JE drafted the manuscript; RRF, RNP and JR contributed to the final version for publication. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. However, Josep Reixach is an employee of Selección Batallé (Riudarenes, Spain) who contributed support and expertise for this project.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Suárez-Mesa, R., Ros-Freixedes, R., Pena, R.N. et al. Impact of the leptin receptor gene on pig performance and quality traits. Sci Rep 14, 10652 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-61509-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-61509-1

Keywords

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.