Abstract

Although the effectiveness of camrelizumab plus apatinib has been confirmed in a phase II clinical study, the efficacy of camrelizumab plus apatinib versus sorafenib for primary liver cancer (PLC) remains unverified. We retrospectively collected the data of 143 patients with PLC who received camrelizumab plus apatinib or sorafenib as the first-line treatment at The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University from April 2018 to November 2021. Of these, 71 patients received an intravenous injection of camrelizumab 200 mg (body weight ≥ 50 kg) or 3 mg/kg (body weight < 50 kg) followed by an oral dosage of apatinib 250 mg/day every 3 weeks and 72 patients received sorafenib 400 mg orally, twice a day in 28-day cycles. The primary outcomes were overall survival and progression-free survival. The secondary outcomes were objective response rate, disease control rate, and safety. The median median progression-free survival and median overall survival with camrelizumab plus apatinib and sorafenib were 6.0 (95% confidence interval (CI) 4.2–7.8) and 3.0 months (95% CI 2.3–3.7) and 19.0 (95% CI 16.4–21.6) and 12.0 months (95% CI 8.9–15.1), respectively (death hazard ratio: 0.61, P = 0.023). Grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events were noted in 50 (70.4%) patients in the camrelizumab plus apatinib group and 19 (26.4%) patients in the sorafenib group. Two treatment-related deaths were recorded. Clinically significant improvements were observed in overall survival and progression-free survival with camrelizumab plus apatinib versus sorafenib. Although the side effects of camrelizumab plus apatinib are relatively high, they can be controlled.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Primary liver cancer (PLC) is one of the most common cancers in the worldwide1,2. The common treatment methods for PLC include surgical resection, liver transplantation, and local ablation. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) is an effective treatment for noncurative PLC3,4. Sorafenib, an oral multi-kinase inhibitor, is the first anti-cancer drug that effectively improved the overall survival (OS) rate 5,6. The main treatment method for various types of cancer includes immunotherapy to enhance host anti-immunity by blocking programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/anti-programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) interaction. Phase I/II trials of PD-1 inhibitor monotherapy, nivolumab or pembrolizumab, in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have shown clinically significant response rates (17–20%)7,8. However, in the subsequent phase III trial, neither of the two drugs reached the study endpoint9,10. Some active intrinsic immune-evasion pathways, including over-expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), are associated with the development and progression of liver cancer. The Imbrave150 study demonstrated that compared with sorafenib, the median OS was significantly improved with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab (19.2 vs. 13.4 months)11,12. Based on this study, the combined treatment of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab is recommended as the first-line standard treatment. However, not all patients are candidates for atezolizumab plus bevacizumab combination therapy and it is not a cost-effective strategy for the first-line systemic treatment of unresectable PLC from the patients’ perspective13. Camrelizumab is a high-affinity, humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to PD-1 and has been approved for the treatment of patients with multiple cancers14,15. The phase II clinical study showed that the objective response rate (ORR) of camrelizumab in patients with advanced HCC who were previously treated was 14.7% and the OS probability at 6.0 months was 74.4%16. Apatinib is a selective vascular endothelial growth factor-2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), with clinical efficacy proven in ovarian and gastric cancers17,18. The phase III trial showed that the median OS of apatinib as a second-line or later treatment for patients with advanced HCC was higher than that of patients treated with a placebo (8.7 vs. 6.8 months)19. Camrelizumab and apatinib alone have limited efficacy. However, a phase II clinical study showed that camrelizumab plus apatinib was a significant and effective alternative to the first-line approved treatment20. There are no available large sample clinical trials comparing sorafenib with camrelizumab plus apatinib in PLC. Therefore, we herein compared the efficacy of camrelizumab plus apatinib versus sorafenib and evaluated the toxicity and side effects.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

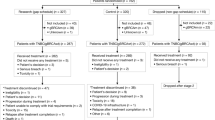

We conducted a single-center retrospective study on 143 patients with PLC who received camrelizumab plus apatinib or sorafenib as the first-line treatment at the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University from April 2018 to November 2021 (Fig. 1). As of the data cut-off on November 30, 2022, 71 patients received camrelizumab plus apatinib and 72 received sorafenib. The baseline characteristics of patients in different treatment groups were similar (Table 1). The research was approved by the Ethical Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University (approval number: quick-PJ 2023-04-32). Due to the retrospective design of the study, patients' written consent was waived.

Study inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients aged > 18 years old; (2) those with a histological or radiological diagnosis as PLC according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases criteria21; (3) those who never received any prior systematic treatment for PLC, had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score of ≤ 2, and classified as Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage A–C; (4) those with at least one measurable lesion according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) v1.1 standard; and (5) those who completed the follow-up until death or study termination. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients who received prior systemic treatment; (2) pregnant and lactating women; (3) those with cognitive dysfunction; (4) those who had other tumors in the past (within 5 years) or at the same time; (5) those with cardiopulmonary insufficiency; (6) those with abnormal coagulation function and bleeding tendency; and (7) those with uncontrollable hypertension.

Treatment administration and outcome measures

Of the 143 patients, 71 received an intravenous injection of camrelizumab 200 mg (body weight ≥ 50 kg) or 3 mg/kg (body weight < 50 kg) (Jiangsu Hengrui Medicine Co., Ltd., Jiangsu, China) followed by an oral dosage of apatinib 250 mg/day (Jiangsu Hengrui Medicine Co., Ltd., Jiangsu, China) every 3 weeks and 72 patients received sorafenib 400 mg orally (Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany), twice a day in 28-day cycles.

The investigator would not give treatment until the clinical benefits were lost after a comprehensive evaluation of radiological and biochemical data and clinical status (such as symptom deterioration, pain secondary to disease, or unacceptable toxicity). The primary outcomes were OS and progression-free survival (PFS) based on the RECIST v1.1 standard. The secondary outcomes were ORR, disease control rate (DCR), and safety. The tumor was evaluated using computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging at baseline, every 6–9 weeks. To continuously evaluate the safety, the patient's vital signs and clinical laboratory test results were recorded and the incidence and severity of adverse events (AEs) were evaluated according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 4.0.

Statistical analysis

The Kaplan–Meier analysis was performed using SPSS 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). All data were represented by mean ± standard deviation and n (%). Student's t-test (or Mann–Whitney test) was used for the comparison of continuous variables and the chi-square test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate OS and PFS. Multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to determine independent prognostic factors.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The data of 143 patients with PLC patients who received camrelizumab plus apatinib (71 patients) or sorafenib (72 patients) as the first-line treatment at The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University from April 2018 to November 2021 were retrospectively collected. As of the data cut-off on November 30, 2022, the median follow-up time was 15.0 months. Among the patients, 39 (54.9%) died in the camrelizumab plus apatinib group and 46 (63.9%) in the sorafenib group. The median age of the entire cohort was 57 (range: 28–84) years, and the majority were men (87.4%). A total of 47 patients underwent pathological diagnosis, including 37 cases of HCC, 9 cases of intrahepatic cholangiocellular carcinoma, and 1 case of mixed cell carcinoma.

Hepatitis B virus is the main cause of PLC, accounting for 69.2% (99/143) of all cases. According to the BCLC staging system, 59.4% (85/143) of patients were classified as BCLC stage C. In terms of liver function, 60.8% (87/143) and 36.4% (52/143) of patients were classified as Child-Pugh A or B, respectively. Vascular invasion and extrahepatic metastasis were noted in 32.9% (47/143) and 46.9% (67/143) patients, respectively. Among the patients, 46 (32.2%) underwent surgery before receiving first-line systemic therapy and 69 (48.3%) underwent transcatheter arterial chemoembolization/transarterial embolization/radiofrequency ablation.

Efficacy

Table 2 shows the treatment response during treatment. According to the RECIST standard 1.1, complete response was achieved in one patient (1.4%) in the sorafenib group and one (1.4%) in the camrelizumab plus apatinib group. The ORR (22.5% vs.11.1%) and DCR (73.2% vs. 51.4%, P = 0.013) of the camrelizumab plus apatinib group were higher than those of the sorafenib group.

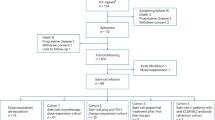

The median OS of the two groups was 19.0 months (95% confidence interval (CI): 16.4–21.6) and 12.0 months (95% CI 8.9–15.1), respectively, indicating a 39% reduction in the risk of death (95% CI 0.399–0.935, P = 0.023, hazard ratio (HR) = 0.610) (Fig. 2). The 12-month and 18-month survival rates of the camrelizumab plus apatinib group were 70.4% (50/71) and 57.7% (41/71), respectively whereas those of the sorafenib group were 48.6% (35/72) and 34.7% (25/72), respectively. The median PFS of the camrelizumab plus apatinib group was 6.0 months (95% CI 4.2–7.8) and that of sorafenib was 3.0 months (95% CI 2.3–3.7) with an HR of 0.65 (P = 0.012) (Fig. 2). The camrelizumab plus apatinib groups showed better clinical benefits than the sorafenib group. Cox multivariate analysis confirmed that the BCLC stage (HR = 0.547, 95% CI 0.329–0.910, P = 0.020) was an independent prognostic factor for OS (Table 3).

Safety

AEs were reported by 90.1% (64/71) of patients in the camrelizumab plus apatinib group and 51.4% (37/72) in the sorafenib group (Table 4). Moreover, 18.3% (13/71) of patients in the camrelizumab plus apatinib group and 11.1% (8/72) of patients in the sorafenib group discontinued treatment due to AEs. The most common treatment-related AEs in the camrelizumab plus apatinib group were hypertension in 48 (67.6%) patients, thrombocytopenia in 40 (56.3%) patients, and elevated serum aspartate aminotransferase level in 39 (54.9%) patients. In the sorafenib group, the most common treatment-related AEs were hand-foot syndrome in 22 (30.6%) patients and elevated serum aspartate aminotransferase levels in 21 (29.2%) patients. Grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 50 (70.4%) patients of the camrelizumab plus apatinib group and 19 (26.4%) of the sorafenib group. The most common grade 3/4 AEs in the camrelizumab plus apatinib group were hypertension (33.8%, n = 24), elevated serum aspartate aminotransferase level (12.7%, n = 9), and thrombocytopenia (9.7%, n = 7). There was a higher rate of hypertension (33.8% vs. 12.5%, p = 0.003) and elevated serum aspartate aminotransferase level (12.7% vs. 2.8%, P = 0.026) as grade 3/4 AEs in the camrelizumab plus apatinib group than in the sorafenib group. In the camrelizumab plus apatinib group, four patients developed upper gastrointestinal bleeding, two discontinued treatment, and one had drug-related death due to upper gastrointestinal bleeding and liver lesions entering pleural cavity rupture. Bleeding events that occur during or after progression may be assessed as those related to progression. One patient in the sorafenib group died of unknown causes after1 month of medication.

Discussion

Targeted combined immunotherapy can improve the viewpoint for the treatment of liver cancer and provides a new treatment standard. Moreover, it has an improved long-term efficacy compared with that of other unresectable liver cancer treatments22,23,24. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and camrelizumab plus apatinib are the currently available first-line treatments for advanced PLC. There are disagreements about which scheme should be selected as the initial treatment method for patients with newly diagnosed PLC. In a phase II clinical study of camrelizumab plus apatinib including 70 first-line and 120 s-line patients, the ORR of the first-line patients was 34.3% and that of the second-line patients was 22.5%. The median PFS of the two groups was 5.7 and 5.5 months, respectively. The 12-month survival rates were 74.7% and 68.2% respectively, and the median OS was not reached20. The United States Food and Drug Administration approved the international multi-center phase III clinical trial of first-line treatment of HCC with camrelizumab plus apatinib to be simultaneously conducted in the United States, Europe, and China, and the experimental results are to be published. Yang et al. enrolled 83 patients and retrospectively analyzed the clinical efficacy of camrelizumab plus apatinib versus sorafenib as the first-line treatment of HCC. The results showed that the median PFS and OS of the camrelizumab plus apatinib group were 8.1 and 13.3 months, respectively, which were significantly higher than those of the sorafenib group (PFS = 5.3, OS = 9.2)25.In the present study, we evaluated the efficacy and toxicity of camrelizumab plus apatinib in the real world in Chinese patients with PLC. In this study, the ORR and DCR of 71 patients in the camrelizumab plus apatinib group (22.5% and 73.2%, respectively) were higher than those of the sorafenib group (11.1% and 51.4%, respectively). The median OS and PFS of the camrelizumab plus apatinib group were 19.0 and 6.0 months, respectively, which was also significantly higher than the median OS (12.0 months) and median PFS (3.0 months) of the sorafenib group. The therapeutic effect of this study was slightly lower than that of the phase II clinical trial. Considering that the group of patients enrolled in our study was more diverse than that of the phase II clinical trial, including those with Child–Pugh Class C, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 2, abnormal laboratory indicators and elderly patients. This suggests that camrelizumab plus apatinib can be safely used, even exceeding the strict inclusion criteria of phase II clinical research. Moreover, COX multivariate analysis confirmed that the BCLC stage was an independent prognostic factor for OS.

In the phase III trial of a single drug, apatinib, as a second-line or late treatment for patients with advanced HCC, treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) occurred in 97% of patients, and grade 3/4 TRAEs were observed in 77% of patients. The most common grade 3/4 TRAEs were hypertension (28%), hand-foot syndrome (18%), and decreased platelet count (13%)19. The phase II clinical trial of a single drug, camrelizumab, used in patients with advanced HCC who had received prior treatment showed that the most common TRAEs at any level were reactive cutaneous capillary endothelial proliferation (67%), elevated serum aspartate aminotransferase level (24%), and proteinuria (23%). Grade 3/4 TRAEs accounted for 22%, with the most common TRAEs being increased elevated serum aspartate aminotransferase level (5%) and decreased neutrophil count (3%)16. The phase II trial of camrelizumab plus apatinib in the treatment of advanced HCC showed that 99.5% of patients had at least one TRAE. Hypertension (72.6%), elevated serum aspartate aminotransferase level (63.2%), proteinuria (61.6%), and hyperbilirubinemia (61.6%) were the most common TRAEs at any level. Patients with grade ≥ 3 TRAEs accounted for 77.4%, with the most common TRAEs being hypertension (34.2%). Severe TRAEs were noted in 28.9% of patients. Treatment-related death occurred in 1.1% of patients20. In the present study, the AEs of patients in the camrelizumab plus apatinib group were consistent with those in phase II clinical trials and higher than those in phase III clinical trials of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab26.Grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 70.4% of the camrelizumab plus apatinib group and 26.4% of the sorafenib group. The most common grade 3/4 AEs in the camrelizumab plus apatinib group were hypertension, elevated serum aspartate aminotransferase level, and thrombocytopenia. The incidence of grade 3 and above AEs in the camrelizumab plus apatinib group was higher than that in the sorafenib, camrelizumab alone, and apatinib alone groups, but most of the AEs in the camrelizumab plus apatinib group could be controlled by drug treatment. In the camrelizumab plus apatinib group, four patients developed upper gastrointestinal bleeding, two patients discontinued treatment, and one patient had drug-related death due to upper gastrointestinal bleeding and liver lesions entering pleural cavity rupture. Variceal bleeding is one of the main causes of death in patients with liver cirrhosis and PLC; however, in a meta-analysis of 27 randomized trials, the total incidence of all-grade and high-grade bleeding events in patients treated with anti-angiogenic TKI was 9.1% and 1.3%, respectively. The risk ratio of all levels of bleeding was higher in patients receiving TKI treatment than that in the controls27,28,29. The mechanism of TKI bleeding remains complex and has not been clarified. Considering that apatinib increases the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, it should be evaluated for patients with a high risk of bleeding using oesophagogastroduodenoscopy before starting the combined treatment of camrelizumab plus apatinib19,30.

Nonetheless, our study has some limitations. First, retrospective data cannot replace first-level evidence from prospective studies. Due to the small sample size, we did not further analyze the differences in OS between patients who met the conditions of phase II clinical trials and those who did not. Second, the real-life background of the study lead to a lack of standardization in clinical practice, and our results should be considered speculative, particularly regarding the identification of prognostic factors.

In conclusion, we confirmed that camrelizumab plus apatinib has better clinical benefits than sorafenib and controllable adverse effects. Therefore, camrelizumab plus apatinib will be a significant and effective first-line treatment option.

References

Zhang, N. & Xiao, X. Integrative medicine in the era of cancer immunotherapy: Challenges and opportunities. J. Integr. Med. 19, 291–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joim.2021.03.005 (2021).

Ogasawara, S. et al. Changes in therapeutic options for hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia. Liver Int. 42, 2055–2066. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.15101 (2022).

Raoul, J. et al. Updated use of tace for hepatocellular carcinoma treatment: How and when to use it based on clinical evidence. Cancer Treat. Rev. 72, 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.11.002 (2019).

Maki, H. & Hasegawa, K. Advances in the surgical treatment of liver cancer. Biosci. Trends 16, 178–188. https://doi.org/10.5582/bst.2022.01245 (2022).

Llovet, J. M. et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 378–90. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0708857 (2008).

Peng, D. et al. Efficacy and safety of apatinib versus sorafenib/placebo in first-line treatment for intermediate and advanced primary liver cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 14, 1101063. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1101063 (2023).

El-Khoueiry, A. B. et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (Checkmate 040): An open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet 389, 2492–2502. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31046-2 (2017).

Zhu, A. X. et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib (Keynote-224): A non-randomised, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 19, 940–952. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30351-6 (2018).

Yau, T. et al. Nivolumab versus sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (Checkmate 459): A randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 23, 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00604-5 (2022).

Finn, R. S. et al. Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in keynote-240: A randomized, double-blind, phase III trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.01307 (2020).

Rinaldi, L. et al. HCC and molecular targeting therapies: Back to the future. Biomedicines 9, 1345. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9101345 (2021).

Finn, R. S. et al. IMbrave150 investigators. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 382(20), 1894–1905. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1915745 (2020).

Wen, F. et al. Atezolizumab and bevacizumab combination compared with sorafenib as the first-line systemic treatment for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A cost-effectiveness analysis in China and the United States. Liver Int. 41, 1097–1104. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.14795 (2021).

Ma, Y. et al. Phase I study of camrelizumab in patients with advanced solid tumors. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 8, 47. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-01213-6 (2023).

Chen, L. et al. Famitinib with camrelizumab and nab-paclitaxel for advanced immunomodulatory triple-negative breast cancer (FUTURE-C-Plus): An open-label, single-arm, phase II trial. Clin Cancer Res. 28(13), 2807–2817. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-4313 (2022).

Qin, S. et al. Camrelizumab in patients with previously treated advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicentre, open-label, parallel-group, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 21, 571–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30011-5 (2020).

Wang, T. et al. Effect of apatinib plus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin vs pegylated liposomal doxorubicin alone on platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer. JAMA Oncol. 8, 1169. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.2253 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Safety and efficacy of apatinib in patients with advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma after the failure of two or more lines of chemotherapy (ahead): A prospective, single-arm, multicentre, phase IV study. BMC Med. 21, 173. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-02841-7 (2023).

Qin, S. et al. Apatinib as second-line or later therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (Ahelp): A multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6, 559–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00109-6 (2021).

Xu, J. et al. Camrelizumab in combination with apatinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (Rescue): A nonrandomized, open-label, phase II trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 27, 1003–1011. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-2571 (2021).

Heimbach, J. K. et al. Aasld guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 67, 358–380. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29086 (2018).

Kelley, R. K. et al. Cabozantinib plus atezolizumab versus sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (Cosmic-312): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 23, 995–1008. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00326-6 (2022).

Casadei-Gardini, A. et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus lenvatinib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A large real-life worldwide population. Eur. J. Cancer 180, 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2022.11.017 (2023).

Yau, T. et al. Nivolumab plus cabozantinib with or without ipilimumab for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: Results from cohort 6 of the checkmate 040 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 41(9), 1747–1757. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.22.00972 (2023).

Yang, Q. et al. A novel therapeutic strategy of combined camrelizumab and apatinib for the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 13, 1136366. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1136366 (2023).

Cheng, A. et al. Updated efficacy and safety data from imbrave150: Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs. sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 76, 862–873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.030 (2022).

Cheon, J. et al. Efficacy and safety of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in Korean patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 42, 674–681. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.15102 (2022).

Hsieh, W. et al. The impact of esophagogastric varices on the prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 7, 42577. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42577 (2017).

Qi, W. X. et al. Incidence and risk of hemorrhagic events with vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine-kinase inhibitors: An up-to-date meta-analysis of 27 randomized controlled trials. Ann. Oncol. 24, 2943–2952. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdt292 (2013).

Gu, Y. L. et al. Apatinib-induced multiple organ hemorrhage: A case report. Am. J. Ther. 30, e89–e90. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0000000000001285 (2023).

Funding

This paper was supported by the Key Project Foundation of Natural Science Research in Universities of Anhui Province (No. KJ2021A0300).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation, or all these areas; took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, D., Wang, Y., Chen, X. et al. Assessing the effectiveness of camrelizumab plus apatinib versus sorafenib for the treatment of primary liver cancer: a single-center retrospective study. Sci Rep 13, 13285 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40030-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40030-x

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.