Abstract

Success in long-term weight management depends partly on psychological and behavioral aspects. Understanding the links between psychological factors and eating behavior tendencies is needed to develop more effective weight management methods. This population-based cross-sectional study examined whether eating self-efficacy (ESE) is associated with cognitive restraint (CR), uncontrolled eating (UE), emotional eating (EE), and binge eating (BE). The hypothesis was that individuals with low ESE have more unfavorable eating behavior tendencies than individuals with high ESE. Participants were classified as low ESE and high ESE by the Weight-Related Self-Efficacy questionnaire (WEL) median cut-off point. Eating behavior tendencies were assessed with Three Factor Eating Questionnaire R-18 and Binge Eating Scale, and additionally, by the number of difficulties in weight management. The difficulties were low CR, high UE, high EE, and moderate or severe BE. Five hundred and thirty-two volunteers with overweight and obesity were included in the study. Participants with low ESE had lower CR (p < 0.03) and higher UE, EE, and BE (p < 0.001) than participants with high ESE. Thirty-nine percent of men with low ESE had at least two difficulties in successful weight control while this percentage was only 8% in men with high ESE. In women, the corresponding figures were 56% and 10%. The risk of low ESE was increased by high UE [OR 5.37 (95% CI 1.99–14.51)], high EE [OR 6.05 (95% CI 2.07–17.66)], or moderate or severe BE [OR 12.31 (95% CI 1.52–99.84)] in men, and by low CR [OR 5.19 (95% CI 2.22–12.18)], high UE [OR 7.20 (95% CI 2.41–19.22)], or high EE [OR 23.66 (95% CI 4.79–116.77)] in women. Low ESE was associated with unfavorable eating behavior tendencies and multiple concomitant difficulties in successful weight loss promotion. These eating behavior tendencies should be considered when counseling patients with overweight and obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is a growing global chronic public health problem. It is a complex disease with multifactorial etiology: genetic component interacts with psychological, behavioral, and obesogenic environmental factors1. Therefore, weight loss interventions need a multidisciplinary approach with psychosocial strategies2. Many individuals with overweight and obesity do not receive the counseling they require3. Despite a high number of often successful weight-loss attempts, long-term weight loss maintenance remains a remarkable challenge4,5. Energy restriction and self-control methods can lead to clinically significant weight loss results in the short run, but these tools can rarely help an individual to achieve sustained weight loss6. It has been suggested that the success in long-term weight management depends primarily on psychological and behavioral aspects7,8. To develop effective and individualized methods for sustained weight management, we need to further understand the link between psychological factors and eating behavior tendencies.

Self-efficacy is a meaningful and adjustable belief in one’s own capabilities to succeed in certain circumstances despite potential barriers9. The concept, originating from Bandura’s social-cognitive theory of human behavior, is widely studied in the field of health behavior. The importance of self-efficacy in predicting health behavior is well recognized10. This belief is constructed by previous successes or failures, and it regulates motivation and behavior11. Self-efficacy can be general or task-specific9, such as eating self-efficacy (ESE)12. ESE is defined as confidence to resist eating in challenging circumstances, such as in the presence of negative emotions and in situations with increased food availability and social pressure12. ESE plays a central role in long-term weight maintenance13,14, since persons with high ESE expectations are more able to engage in favorable lifestyle modifications and maintain the achieved weight-loss compared with individuals with low ESE expectations13,15,16,17,18. Despite this central role, existing literature is conflicting as to whether success in weight-loss is dependent on the state of ESE16,19,20,21. It has been suggested that ESE is related to differences in clinical response to obesity treatment22.

Eating behavior is a multidimensional concept expressing helpful behavior such as cognitive restraint (CR) and maladaptive behavior such as uncontrolled eating (UE), emotional eating (EE), and binge eating (BE)23,24. CR describes intentions to restrict intake25 and is a method to lose or control weight24. UE describes the inability to control eating, leading to eating influenced by external triggers, whereas EE describes the disposition to eat triggered by negative mood states26. High tendencies for UE and EE reflect the susceptibility to eat in response to both external and internal cues27. BE is characterized by frequent episodes of eating large amounts of food to the point of discomfort28. Prior literature shows that scores of UE, EE, and BE are at lower level among individuals who successfully lose or maintain weight than among individuals who fail to achieve these goals29.

In weight loss interventions, the level of ESE has often been studied as a predictor of weight loss success13,16,20,30,31,32. However, studies reporting on the association of the level of ESE and eating behavior tendencies are scarce. We aimed to test the hypothesis that individuals with low level of ESE have more unfavorable eating behavior tendencies compared with individuals with high ESE. In addition to individual examination of eating behavior tendencies, our aim was to show that individuals with low ESE have multiple concomitant eating behavior difficulties such as low CR, high UE, high EE, and moderate or severe tendency for BE.

Methods

This cross-sectional study used data from volunteers enrolled in the Prevention of Metabolic Syndrome (PrevMetSyn, ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01959763), a randomized controlled trial from February 2013 to April 2014. The Ethics Committee of the Northern Ostrobothnia Hospital District has approved the original study plan of PrevMetSyn (approval number 29/2012) and all procedures in this trial were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association 2013). This study followed the principles of Good Clinical Practice in the execution of the trial. The subjects received both oral and written information, and written informed consent was obtained. A hyperlink to questionnaires was sent to study persons by e-mail after the first study visit and the data collected were analyzed in coded form, i.e., pseudonymized, and pertinent data protection protocols were followed.

Study design and participants

The PrevMetSyn trial was a one-year randomized clinical trial on the effect of cognitive behavioral therapy-based group counseling and lifestyle counseling via a web-based health behavior change support system (HBCSS). The details of the PrevMetSyn trial have been published previously33. The PrevMetSyn trial included 532 participants living in the Oulu area in Northern Finland. The participants of this study were recruited from the Finnish Population Register Center and an invitation letter was sent to 11,400 residents (evenhandedly for both genders) aged 20–60 years. A total of 1065 volunteered for the study and 580 met the eligibility criteria evaluated by a telephone interview. Inclusion criteria were overweight or obesity (body mass index (BMI) of 27–35 kg/m2), presence of at least one component of metabolic syndrome, access to the internet, and the ability to use basic information and communications technology such as email and internet. Participants were excluded if they had abnormal laboratory values (thyroid, kidney, and liver function tests) or clinically significant illness with contraindication for weight loss or physical activity. Additionally, exclusion criteria included health-related restrictions to losing weight (e.g., pregnancy), participation in other concurrent weight loss programs, or use of weight loss medications. Power calculation in the PrevMetSyn study was estimated using change in body weight33.

Measures

Eating self-efficacy (Weight Efficacy Lifestyle Questionnaire, WEL)

Self-efficacy in relation to eating was assessed by the Weight Efficacy Lifestyle (WEL) questionnaire. WEL is a self-report measure of 20 items24,34. It consists of five subscales each including four items relating to negative emotions (e.g., eating when anxious); food availability (e.g., eating on the weekends); social pressure (e.g., eating when others are pressuring to eat); physical discomfort (e.g., eating when in pain); and positive activities (e.g., eating when watching TV). The participants filled in the questionnaire reporting their confidence and ability to resist eating using a 10-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not confident) to 9 (very confident). Total scores range from 0 to 180, with higher scores indicating stronger ESE beliefs. WEL has been validated to be a reliable measure in samples of weight-loss intervention participants34. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95 for eating self-efficacy in this study.

The participants were divided into two groups based on their score on the WEL questionnaire. We categorized WEL domains as “low ESE” and “high ESE” by using the median as the cutoff point (scores 0–121 = low ESE, scores 122–180 = high ESE). There is no prior literature suggesting an optimal cutoff point for this questionnaire.

Eating behavior tendencies (Three Factor Eating Questionnaire-R18, TFEQ-R18 and Binge Eating Scale, BES)

The TFEQ-R18 is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 18 items to assess eating behavior features24. The instrument measures three features: CR, UE, and EE. The participants answered 17 items using a 4-point Likert scale for how often they engage in specific eating behaviors and one item using an 8-point Likert scale. CR (six items) is defined as “control over food intake in order to lose weight or prevent weight gain”, UE (nine items) as “overall loss of control in the regulation of eating”, and EE (three items) as “eating in response to negative emotions”. The points of Likert scale were recoded and the sum of every feature (CR, UE, EE) formed the raw score for all features, which were converted to relative proportion (%) of the highest possible raw scores (100%). The scaled scores of each construct range from 0 to 100%, with higher scores reflecting higher intensity of each eating behavior tendency. The TFEQ-R18 is considered to be a reliable measure to describe eating behavior of individuals with obesity24. Cronbach’s alphas were 0.65 for cognitive restraint, 0.84 for uncontrolled eating, 0.86 for emotional eating, and 0.87 for binge eating in this study.

The BES is a self-report questionnaire of 16 items to assess the tendency for binge eating28. The participants choose a proper alternative from three or four statements. Statements assessed the presence and severity of behavioral, emotional, and cognitive symptoms of binge eating episodes among individuals with overweight or obesity28,35. In this study, we applied the cutoff scores of the Finnish Current Care Guidelines of Obesity, where no binge eating is defined with scores 0–19, moderate severity of binge eating with points 20–29, and high severity of binge eating with points 30–4636.

Defining eating behavior tendencies as difficulties

In addition to examining the scores of each eating behavior tendency, we wanted to consider the intensity of each tendency (CR, UE, EE, and BE) as a difficulty for successful weight control or weight loss. However, the TFEQ-R18 questionnaire and prior literature do not suggest validated cutoff points. Therefore, we divided each TFEQ-R18 tendency into tertiles (low = the tertile with the lowest scores, intermediate = the tertile with intermediate scores, high = the tertile with the highest scores) based on the baseline questionnaire data and used them as categorical variables as follows: low CR (the tertile with the lowest scores, 0–38.9 points) reflecting low attempts to control eating, whereas high UE (the tertile with the highest scores, 51.9–100 points) reflects the susceptibility for external cues for eating and high EE (the tertile with highest scores, 55.6–100 points) reflects the sensibility for internal cues for eating. Additionally, moderate or high severity of binge eating based on the BES questionnaire (merged as one level of difficulty, 20–46 points) was defined as one difficulty. Each of these variables forms one difficulty; the total range of difficulties can therefore vary from 0 to 4.

Anthropometric data

The study personnel at the research unit measured height and weight with calibrated equipment. They measured waist circumference with a measuring tape in the horizontal plane midway between the lowest ribs and the iliac crest in standing position on bare skin. They measured resting blood pressure twice after a few minutes of rest. Study nurses drew blood samples after at least ten hours of fasting, and blood samples were analyzed at the clinical laboratory of the Oulu University Hospital (NordLab).

Metabolic syndrome was diagnosed if any three criteria of the following five components were fulfilled: waist circumference ≥ 102 cm in men and ≥ 88 cm in women; serum triglycerides ≥ 1.7 mmol/L or drug treatment for elevated triglycerides; serum HDL < 1.0 mmol/L in men and < 1.3 mmol/L in women or drug treatment for low HDL; blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or drug treatment for elevated blood pressure; fasting plasma glucose ≥ 5.6 mmol/L, or drug treatment for elevated blood glucose37,38.

Missing data

The rates of collected data were as follows: anthropometric data 530 out of 532 (missing data 0.4%), WEL questionnaire 469 out of 532 (missing data 11.8%), BES questionnaire 460 out of 532 (missing data 13.5%), and TFEQ-R18 questionnaire 528 out of 532 (missing data 0.8%). Only participants with complete data were included in the analyses when comparing participants with the level of ESE.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics, Version 27 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations and were analyzed by independent samples T-Test. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages for descriptive purposes and were compared by the Pearson Chi-Square Test. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant. Normal distribution was evaluated using skewness and kurtosis.

Multiple linear regression analysis using the enter method was conducted to investigate associations between ESE and eating behavior tendencies. ESE was the dependent variable and CR, UE, EE, and BE were the independent variables. Unstandardized coefficients, their 95% confidence intervals (CI), standard errors, and standardized coefficients were reported.

Binary logistic regression analysis using the enter method was performed with low ESE vs. high ESE as the outcome variable. The independent variables were all tertiles of cognitive restraint (the tertile with the highest scores was used as a reference), all tertiles of uncontrolled eating (the tertile with the lowest scores was used as a reference), all tertiles of emotional eating (the tertile with the lowest scores was used as a reference), and all categories of binge eating (no binge eating was used as a reference). Odds ratios and their 95% CIs were reported. There were no significant two-way interaction terms. Goodness-of-fit and explanatory power was assessed with the Hosmer–Lemeshow test and Nagelkerke R2 coefficient, respectively. The assumptions of the regression models were checked. All analyses were stratified by gender.

Results

Sample characteristics

Half of the 532 participants were men (51%) and half were women (49%), and about half of the participants were subjects with overweight (48%) and half were living with obesity (52%) (Table 1). Mean age of the participants was 46.0 (SD 10.0) years with no difference in age between the genders. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome was significantly higher among men compared with women (55% vs. 36%, p < 0.001) as previously reported39. Women reported higher scores in CR, UE, and EE (p < 0.007) and were more likely to have moderate or high tendency for BE (p < 0.001) than men.

Eating behavior features by eating self-efficacy categories

The total ESE score ranged between 5 and 180 (median 121) (Table 2). Low ESE was more common in women (63%) than in men (36%, p < 0.001). The first step in the analysis was to examine the association between low ESE and high ESE and the summary scores of each eating behavior tendency. Participants with low ESE reported lower scores than those with high ESE in cognitive restraint (p < 0.027) and considerably higher scores in both uncontrolled eating and emotional eating (p < 0.001). In both genders, participants with low ESE were more likely to have moderate or high tendency for binge eating compared with participants with high ESE (p < 0.001). In both genders, there was no difference between low ESE and high ESE in age, BMI, and in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome.

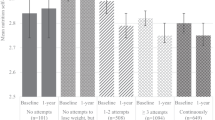

The number of difficulties by ESE categories and gender

Eating behavior tendencies were defined as difficulties in successful weight control or weight loss promotion as follows: low scores of CR (the tertile with the lowest scores), high scores of UE (the tertile with the highest scores) and high scores in EE (the tertile with the highest scores) and moderate or high severity of BE (merged). In men, the most frequent difficulty was low CR in both ESE categories but there was no significant difference between categories (Table 2). In men with low ESE, high UE was more than two times more common, high EE five times more common, and symptoms of BE 16 times more common than in men with high ESE (p < 0.001). In women, the most common difficulty in both ESE categories was high EE (p < 0.001). In women with low ESE, low CR and high EE were twice as common, high UE five times more common, and symptoms of BE six times more common than in women with high ESE (p < 0.001).

The next step in data analysis was to examine the concomitant number of difficulties in both low ESE and high ESE stratified by gender. Persons with low ESE in both genders were more likely to have a higher number of eating behavior difficulties compared to subjects with high ESE (p < 0.001, Fig. 1). In men with low ESE, 39% had at least two difficulties, and 12% had three or four difficulties. Furthermore, in women with low ESE, 56% had at least two difficulties, and 31% had three or four. In both genders, half of the subjects with high ESE had no difficulties.

The number of difficulties by eating self-efficacy categories and gender. The difficulties are classified as follows: low cognitive restraint (the tertile with the lowest scores), high uncontrolled eating (the tertile with the highest scores), high emotional eating (the tertile with the highest scores), and moderate or high severity of binge eating (merged). Each of these variables forms one difficulty, therefore the total range of difficulties can vary from 0 to 4. The difference between low ESE and high ESE was tested with Pearson Chi-Square Test, P < 0.001.

Eating behavior tendencies associated with ESE

In linear regression analysis, UE, EE, and BE had independent negative associations with ESE (Table 3). Additionally, CR was positively associated with ESE among women (p < 0.001) but not in men (p = 0.711).

The last step in data analysis was to examine the associations of each difficulty and low ESE. In women, intermediate or low scores in CR were associated with a 3- to 5-fold risk of low ESE (p < 0.013, Table 4). In men, intermediate scores in UE were associated with about 5-fold risk of low ESE, and in both men and women, high scores in UE were associated with a 5- to 7-fold risk of low ESE (p < 0.001). In turn, in women, intermediate scores in EE were associated with a 12-fold risk of low ESE, and in both men and women, high scores in EE were associated with a 6- to 24-fold risk of low ESE (p < 0.002). Given the small size of the group with high severity of BE, moderate and high severity of BE were merged as one category. In men, moderate or severe BE was associated with a 12-fold risk of low ESE (p = 0.019).

Linear regression models were significant among men (R2 = 0.49, F(4, 224) = 54.56, p < 0.001) and women (R2 = 0.50, F(4, 222) = 54.75, p < 0.001). In men, the logistic regression model using the enter method including eating behavior tendencies, i.e., cognitive restraint, uncontrolled eating, emotional eating, and binge eating as variables to be associated with low ESE was statistically significant, χ2 (7, N = 229) = 67.14, p < 0.001. The model explained 34.9% (Nagelkerke R square) of the variance in the dependent variable and correctly classified 76.4% of the cases. In women, the entered logistic regression to analyze low ESE was statistically significant χ2 (8, N = 227) = 94.59, p < 0.001. The model explained 46.5% (Nagelkerke R square) of the variance in the dependent variable and correctly classified 59.0% of the cases.

Discussion

Our main result was that individuals with low ESE had more often unfavorable eating behavior tendencies and more concomitant eating behavior difficulties than individuals with high ESE. This finding might help to understand the psychological and behavioral aspects behind obesity. Those who reported low intensity of cognitive restraint (CR) or high intensity of uncontrolled eating (UE), emotional eating (EE), or binge eating (BE) had higher risk of experiencing low confidence to resist eating in challenging circumstances.

Previous studies show that low ESE is associated with UE and EE40,41 and binge eating symptoms22,40,42. Our results are in line with these findings. However, in previous studies eating behavior tendencies have been investigated separately in relation to ESE30,40,41 but their concomitant association with ESE was not studied. Therefore, we examined the co-existence of multiple eating behavior difficulties and their association with ESE. Our finding that individuals with low ESE in both genders were more likely to have a higher number of eating behavior difficulties compared to subjects with high ESE is novel. Previously, individuals with low scores in CR and high scores in UE and EE were described as a group with low efforts to control eating and who are susceptible to external and internal triggers to eating27. Additionally, high scores in CR combined with high scores in UE and EE was recognized as a detrimental combination because of its association with poorer food choices and coping strategies. These findings suggest the relevance of the results of our study.

Future studies should investigate which eating behavior clusterings are harmful and which are protective in terms of ESE. Moreover, the associations of eating behavior clustering and weight need future studies because Pentikäinen et al.27 did not report the BMI of study subjects, whereas in our study the population was composed of individuals with overweight and obesity. Acknowledging the coincidental eating behavior difficulties and their prevalence as well as the level of ESE may help to improve the fit between the individual and weight management programs43.

Gender seems to affect ESE as the prevalence of low ESE was almost 2-fold in women compared to men. In previous studies, however, conflicting results on gender differences in ESE have been reported30,44,45. In addition to women having much higher prevalence of low ESE in comparison to men, women also had higher risk of multiple concomitant eating behavior difficulties. These results might be explained by gender differences in eating behavior, which are in line with previous results46,47. Most of women with low ESE tend to have difficulties with eating control and are susceptible for challenges in regulation and lack of the ability to resist eating. Most of men with low ESE may turn out to be susceptible for challenges in regulation and lack of the ability to resist eating, however, less frequently than women with low ESE.

As previously reported, ESE has varied in participants in weight-loss interventions30, therefore it is possible that in some individuals high ESE and high BMI may also be concurrent. Many participants in weight-loss interventions have usually had previous weight loss attempts, which may explain the wide variety in ESE. Therefore, our finding of association of BMI and ESE may not exclude the possibility that people with high ESE might succeed better in weight loss, as previously reported. The latter may have significance in clinical setting.

In clinical practice, besides BMI, metabolic markers, dietary quality, and demographic information, psychosocial variables such as self-efficacy are important in order to form a holistic view of a patient´s situation. Based on the results of this study, it is equally relevant to recognize individuals with low ESE and those with high ESE in order to provide tailored counseling. This underlines the importance of health care professionals’ competence to recognize psychological factors affecting eating as well as valid tools to recognize different tendencies and capabilities of the patient in order to provide tailored care. One possible alternative improving self-efficacy and favorable eating behavioral tendencies might be cognitive behavioral techniques which enhance patients’ competence autonomy and intrinsic motivation2.

Our study has some important strengths including a large population-based study sample, a high number of men, and a diverse combination of eating behavior factors. Additionally, the rates of missing data are low. Therefore our results may be generalizable to people seeking treatment for obesity, at least in Western countries. The most notable limitation concerns the use of a dichotomous split for the ESE. This approach might affect statistical power and the categorization might be too strict. However, there is no prior literature suggesting an optimal cutoff point for this questionnaire. Therefore, multiple linear regression analysis using the enter method was also conducted to investigate associations between ESE and eating behavior tendencies. Another limitation is the cross-sectional nature of the analysis, which rules out causal conclusions.

Conclusions

Low ESE was associated with unfavorable eating behavior tendencies and multiple concomitant eating behavior difficulties to successful weight loss promotion. These eating behavior tendencies associated with low ESE should be considered when counseling patients with overweight and obesity. Additionally, the competence of health professionals to recognize and provide tailored care for individuals with feelings of low capabilities and unfavorable eating behavior tendencies may have an impact on the response to successful weight management. More research is needed on which tailored obesity treatment approaches are the most effective for individuals with low ESE and multiple concomitant eating behavior difficulties.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

WHO. WHO European Regional Obesity Report 2022. (2022).

Castelnuovo, G. et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy to aid weight loss in obese patients: Current perspectives. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 10, 165–173 (2017).

Zoltick, D. et al. Healthy lifestyle counseling by healthcare practitioners: A time to event analysis. J. Prim. Care Community Health. 12, 1–7 (2021).

Yaemsiri, S., Slining, M. M. & Agarwal, S. K. Perceived weight status, overweight diagnosis, and weight control among US adults: The NHANES 2003–2008 Study. Int. J. Obes. 35, 1063–1070 (2011).

Santos, I., Sniehotta, F. F., Marques, M. M., Carraça, E. V. & Teixeira, P. J. Prevalence of personal weight control attempts in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Rev. 18, 32–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12466 (2017).

Langeveld, M. & Devries, J. H. The long-term effect of energy restricted diets for treating obesity. Obesity 23, 1529–1538. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21146 (2015).

Elfhag, K. & Rössner, S. Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain. Obesity Rev. 6, 67–85 (2005).

Montesi, L. et al. Long-term weight loss maintenance for obesity: A multidisciplinary approach. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 9, 37–46 (2016).

Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 84, 191–215 (1977).

Zhang, C. Q., Zhang, R., Schwarzer, R. & Hagger, M. S. A meta-analysis of the health action process approach. Health Psychol. 38, 623–637 (2019).

Bandura, A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychol. Health 13, 623–649 (1998).

Clark, M. M., Abrams, D. B., Niaura, R. S., Eaton, C. A. & Rossi, J. S. Self-efficacy in weight management. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 59, 739–744 (1991).

Latner, J. D., McLeod, G., O’Brien, K. S. & Johnston, L. The role of self-efficacy, coping, and lapses in weight maintenance. Eat. Weight Disord. 18, 359–366 (2013).

Varkevisser, R. D. M., van Stralen, M. M., Kroeze, W., Ket, J. C. F. & Steenhuis, I. H. M. Determinants of weight loss maintenance: A systematic review. Obesity Rev. 20, 171–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12772 (2019).

Richman, R. M., Loughnan, G. T., Droulers, A. M., Steinbeck, K. S. & Caterson, I. D. Self-efficacy in relation to eating behaviour among obese and non-obese women. Int. J. Obes. 25, 907–913 (2001).

Linde, J. A., Rothman, A. J., Baldwin, A. S. & Jeffery, R. W. The impact of self-efficacy on behavior change and weight change among overweight participants in a weight loss trial. Health Psychol. 25, 282–291 (2006).

Warziski, M. T., Sereika, S. M., Styn, M. A., Music, E. & Burke, L. E. Changes in self-efficacy and dietary adherence: The impact on weight loss in the PREFER study. J. Behav. Med. 31, 81–92 (2008).

Sheeran, P. et al. The impact of changing attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy on health-related intentions and behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 35, 1178–1188 (2016).

Szabo-Reed, A. N. et al. Longitudinal weight loss patterns and their behavioral and demographic associations. Ann. Behav. Med. 50, 147–156 (2016).

Byrne, S., Barry, D. & Petry, N. M. Predictors of weight loss success. Exercise vs. dietary self-efficacy and treatment attendance. Appetite 58, 695–698 (2012).

Annesi, J. J. & Stewart, F. A. Contrasts of initial and gain scores in obesity treatment-targeted psychosocial variables by women participants’ weight change patterns over 2 years. Fam. Community Health 46, 39–50 (2023).

Miller, P. M., Watkins, J. A., Sargent, R. G. & Rickert, E. J. Self-efficacy in overweight individuals with binge eating disorder. Obes. Res. 7, 552–555 (1999).

Vartanian, L. R. & Porter, A. M. Weight stigma and eating behavior: A review of the literature. Appetite 102, 3–14 (2016).

Karlsson, J., Persson, L.-O., Sjo, L., Èm, È. & Sullivan, M. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) in obese men and women. Results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study. Int. J. Obes. 24, 1715–1725 (2000).

Schaumberg, K., Anderson, D. A., Anderson, L. M., Reilly, E. E. & Gorrell, S. Dietary restraint: What’s the harm? A review of the relationship between dietary restraint, weight trajectory and the development of eating pathology. Clin. Obes. 6, 89–100 (2016).

Cappelleri, J. C. et al. Psychometric analysis of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire-R21: Results from a large diverse sample of obese and non-obese participants. Int. J. Obes. 33, 611–620 (2009).

Pentikäinen, S., Arvola, A., Karhunen, L. & Pennanen, K. Easy-going, rational, susceptible and struggling eaters: A segmentation study based on eating behaviour tendencies. Appetite 120, 212–221 (2018).

Gormally, J., Black, S., Daston, S. & Rardin, D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict. Behav. 7, 47–55 (1982).

Keränen, A. M. et al. The effect of eating behavior on weight loss and maintenance during a lifestyle intervention. Prev. Med. (Baltim.) 49, 32–38 (2009).

Bas, M. & Donmez, S. Self-efficacy and restrained eating in relation to weight loss among overweight men and women in Turkey. Appetite 52, 209–216 (2009).

Wingo, B. C. et al. Self-efficacy as a predictor of weight change and behavior change in the PREMIER trial. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 45, 314–321 (2013).

Nezami, B. T. et al. The effect of self-efficacy on behavior and weight in a behavioral weight-loss intervention. Health Psychol. 35, 714–722 (2016).

Teeriniemi, A. M. et al. A randomized clinical trial of the effectiveness of a Web-based health behaviour change support system and group lifestyle counselling on body weight loss in overweight and obese subjects: 2-year outcomes. J. Intern. Med. 284, 534-545 (2018).

Clark, M. M., Abrams, D. B., Niaura, R. S., Eaton, C. A. & Rossi, J. S. Self-efficacy in weight management. J. Consulting Clin. Psychol. 59, 739-744 (1991).

Marcus, M. D., Wing, R. R. & Lamparski, D. M. Binge eating and dietary restraint in obese patients. Addict. Behav. 10, 163–168 (1985).

A working group set up by Duodecim of the Finnish Medical Society, the F. O. R. A. and the F. P. Society. H. S. L. D. Obesity (children, adolescents and adults). Valid treatment recommendation. Accessed 2 March 2023. https://www.kaypahoito.fi/hoi50124.

Grundy, S. M. et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement. Circulation 112, 2735–2752. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404 (2005).

(NCEP), N. C. E. P. Executive summary of the third report (NCEP)-adult treatment panel III. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 285, 2486-97 (2001).

Seo, Y. G. et al. Lifestyle counselling by persuasive information and communications technology reduces prevalence of metabolic syndrome in a dose–response manner: A randomized clinical trial (PrevMetSyn). Ann. Med. 52, 321–330 (2020).

Poínhos, R., Oliveira, B. M. P. M. & Correia, F. Eating behavior in Portuguese higher education students: The effect of social desirability. Nutrition 31, 310–314 (2015).

Annesi, J. J., Mareno, N. & McEwen, K. Psychosocial predictors of emotional eating and their weight-loss treatment-induced changes in women with obesity. Eat. Weight Disord. 21, 289–295 (2016).

Ames, G. E., Heckman, M. G., Grothe, K. B. & Clark, M. M. Eating self-efficacy: Development of a short-form WEL. Eat Behav. 13, 375–378 (2012).

Bouhlal, S., McBride, C. M., Trivedi, N. S., Agurs-Collins, T. & Persky, S. Identifying eating behavior phenotypes and their correlates: A novel direction toward improving weight management interventions. Appetite 111, 142–150 (2017).

Ames, G. E., Heckman, M. G., Diehl, N. N., Grothe, K. B. & Clark, M. M. Further statistical and clinical validity for the Weight Efficacy Lifestyle Questionnaire-Short Form. Eat Behav. 18, 115–119 (2015).

Clark, M. M. & King, T. K. Eating self-efficacy and weight cycling: A prospective clinical study. Eat Behav. 1, 47–52 (2000).

Oura, P., Niinimäki, J., Karppinen, J. & Nurkkala, M. Eating behavior traits, weight loss attempts, and vertebral dimensions among the General Northern Finnish Population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 44, E1264–E1271 (2019).

Anversa, R. G. et al. A review of sex differences in the mechanisms and drivers of overeating. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 63, 1-16 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research is connected with the DigiHealth and Fibrobesity projects, strategic profiling projects at the University of Oulu, Finland. The project is supported by the Academy of Finland (project number Profi5: 326291 and Profi6: 336449), the Diabetes Research Foundation, the Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research, the Suorsa Healthcare Foundation, and the University of Oulu.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.J., A.M.T., M.J.S., and T.S. participated in the design of the study and N.O., T.J., A.M.T., M.J.S., T.S., and M.N. participated in data collection. N.O. and L.H. conducted the statistical analysis and N.O. wrote the first draft. All other authors took part in manuscript preparation and advising on statistical analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oikarinen, N., Jokelainen, T., Heikkilä, L. et al. Low eating self-efficacy is associated with unfavorable eating behavior tendencies among individuals with overweight and obesity. Sci Rep 13, 7730 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34513-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34513-0

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.