Abstract

The study aimed to investigate the associations between maternal lifestyles and antenatal stress and anxiety. 1491 pregnant women were drawn from the Guangxi birth cohort study (GBCS). A base line questionnaire was used to collect demographic information and maternal lifestyles. The Pregnancy Stress Rating Scale (PSRS) and Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) were used to assess prenatal stress and anxiety, respectively. Regression analyses identified the relationship between maternal lifestyles and prenatal stress and anxiety: (1) Hours of phone use per day was positively correlated to prenatal stress and anxiety and increased with stress and anxiety levels (all P trend < 0.05). In addition, not having baby at home was positively correlated to prenatal stress. (2) Self-reported sleep quality was negative with prenatal stress and anxiety, and decreased with stress and anxiety levels (all P trend < 0.01). Moreover, not frequent cooking was negatively correlated to prenatal stress and having pets was negatively correlated to prenatal anxiety (P < 0.05). However, having pets was not correlated to prenatal stress (P > 0.05). Our results showed that adverse lifestyles increase the risk of antenatal stress and anxiety, a regular routine and a variety of enjoyable activities decreases the risk of prenatal stress and anxiety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stress and anxiety are relatively common in pregnant women during the prenatal period1,2,3,4,5, this topic is currently receiving a large amount of attention from researchers. The immediate and longer-term consequences of antenatal stress and anxiety are far-reaching, not only affecting the mother but also her infant. Stress and anxiety during pregnancy could diminish one’s capacity for self-care, which could lead to inadequate nutrition, all of which could have influence on the gestation and delivery such as intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR)6,7, premature births7,8,9, low birth weight9 et al. Meanwhile, it could affect the nervous system development of infants and the psychological development of children10. Moreover, a recent study has revealed antenatal stress and anxiety could lead to postpartum psychological disorders and psychosis11. All of the above analyses highlight the importance of prenatal mental health care.

Improving care for prenatal mood disorders should depend on more effective risk factor prediction. Previous studies reported that sociodemographic factors, such as maternal age, marital status, education level12, household incoming13 and increased body mass index (BMI)9,14 were associated with prenatal stress or anxiety15. Moreover, maternal lifestyles during pregnancy, including eating disorders5, smoking and alcohol consumption16,17 and changes in social relationships14,15 also impacted the psychosocial characteristics of pregnant women. Increasing literatures to suggest a consensus that experience of adverse lifestyles can trigger stress or anxiety symptoms6,15,16,18,19. Finally, although information on risk factors for prenatal stress and anxiety is available in previous literatures, most studies only focused on one single risk factor.

As society develops, the lifestyles of maternal women have drastically changed. In the information rapid development day, the phone usage and working pace is increasing20,21 and the sleep quality is disturbing22. In some families, pregnant women have many burden, such as working, bring up babies, cooking and gestation. There are numerous studies reported that parts of new lifestyles was harmful to human physical health. Previous literatures have reported that using phone in the prenatal stage caused pathological changes in kidney tissues due to oxidative stress23,24, and that higher levels of electromagnetic radiation could lead to morphological changes in lymphocytes25. Moreover, animal experiment showed that extended electromagnetic radiation exposure induced oxidative stress in tissues of pregnant mice and their offspring23,26. Lack of sleep during pregnancy could have effect on endocrine system disorder, such as hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis abnormal response27. Always cooking would be more vulnerable to coronary heart disease28 and poor sleep quality29. We hypothesis these changed lifestyles would have effect on maternal prenatal psychological health. However, few studies are available on the influence of maternal new lifestyles on prenatal stress and anxiety, and simultaneously targeted the women with various new lifestyles on the risk of prenatal stress and anxiety.

Based on the above analysis, our study aimed to estimate whether maternal new lifestyle factors during pregnancy affected prenatal stress and anxiety in the Guangxi birth cohort study (GBCS), and to explore the associations between various lifestyles and antenatal stress and anxiety.

Results

Basic demographic characteristics

Descriptive analysis revealed that maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI and gravidity history had significant statistical difference in sub-stress level groups. Inversely, other baseline characteristics had no significant differences in sub-stress groups and all of the demographic characteristics had no significant differences during anxiety and no anxiety groups (Table 1).

Selected maternal lifestyles

Comparisons between each stress group revealed that frequent cooking (χ2 = 9.943, P = 0.007), not having pets (χ2 = 10.782, P = 0.005), not having a baby at home (χ2 = 43.085, P < 0.001), a high level of phone usage per day (hours) (χ2 = 38.936, P < 0.001) and bad self-reported sleep quality (χ2 = 12.776, P = 0.012) were more likely to experience prenatal stress symptoms. Wearing radiation-proof clothing during pregnancy (χ2 = 5.378, P = 0.068) and having afternoon naps (χ2 = 3.029, P = 0.220) was not statistically different in different stress level groups (Table 2).

For anxiety levels, not having pets (χ2 = 8.698, P = 0.003), increased phone usage per day (hours) (χ2 = 6.697, P = 0.035) and bad self-reported sleep quality (χ2 = 11.43, P = 0.003) was correlated to prenatal anxiety symptoms in two groups. Inversely, frequent cooking (χ2 = 2.592, P = 0.107), wearing radiation-proof clothing during pregnancy (χ2 = 2.622, P = 0.105), taking afternoon naps (χ2 = 0.075, P = 0.785) and having baby at home (χ2 = 4.047, P = 0.132) had no statistical differences in groups with and without anxiety (Table 2).

The relationship between maternal lifestyles and prenatal stress

Ordinal logistic regression model analyses showed that less than 6 hours of phone usage per day (OR = 1.82, 95%CI: 1.32, 2.50) and more than 6 hours per day (OR = 2.43, 95%CI: 1.65, 3.58) and not having a baby at home (OR = 1.66, 95%CI: 1.05, 2.65) were positively correlated to prenatal stress, and positively correlated to an increased stress level, all P value was < 0.05 and all P trend of phone usage per day and having babies at home was < 0.01. However, good or generally self-reported sleep quality (OR = 0.59, 95%CI: 0.44, 0.80 and OR = 0.72, 95%CI: 0.54, 0.96, respectively) and not frequent cooking (OR = 0.65, 95%CI: 0.53, 0.80) were negatively correlated to prenatal stress, and positively correlated to a decreased stress level, all P value was < 0.05 and P trend of self-reported sleep quality was <0.01. However, having pets was not correlated to prenatal stress (P > 0.05). The confounding factors including maternal age, pre-pregnant body mass index and gravidity history were adjusted in the ordinal logistic regression analysis (Table 3).

The relationship between maternal lifestyles and prenatal anxiety

The results of binary logistic regression analyses examining the relationship between maternal lifestyles and prenatal anxiety are presented in Table 4. Participants who had less than 6 hours phone usage per day (OR = 2.42, 95%CI: 1.04, 5.65, P = 0.041) and more than 6 hours per day (OR = 2.62, 95%CI: 1.05, 6.55, P = 0.039) were almost twice as be likely to experience prenatal anxiety than participants with no phone usage, and were positively correlated to the level of prenatal anxiety, P trend was 0.016. Having pets (OR = 0.46, 95%CI: 0.26, 0.84, P = 0.011) and good or generally self-reported sleep quality (OR = 0.46, 95%CI: 0.27, 0.77, P = 0.003 and OR = 0.53, 95%CI: 0.33, 0.85, P = 0.008, respectively) were significantly associated with a decreased likelihood of prenatal anxiety, and associated with a decreased level of prenatal anxiety, P trend < 0.01. Maternal age and gravidity history were considered as confounding factors and adjusted in the logistic regression models (Table 4).

Discussion

From this cross-sectional study, we found that parts of maternal lifestyles during pregnancy had an impact on prenatal stress and anxiety. In particular, our results indicated that adverse lifestyles could increase the risk of stress and anxiety during pregnancy, and a variety of enjoyable activities and regular routines could relax pregnant women and decrease the risk of prenatal stress and anxiety. Our results showed that increased daily phone usage was a major risk factor in prenatal stress and anxiety. Moreover, good or generally self-reported sleep quality was negatively correlated to prenatal stress and anxiety, not frequent cooking and having pets was negatively correlated to prenatal stress and anxiety, respectively. Interestingly, we also found not having baby at home increase the risk of prenatal stress. Our findings are consistent with the findings of previous reports stating that adverse behaviour, such as prenatal or perinatal drinking16,30,31 or smoking17 could influence the psychology state of pregnant women. Moreover, our study revealed that prenatal mental health problems were prevalent in Guangxi. Indeed, all (100%) participants had elevated stress during their pregnancies and nearly a tenth of participants (7.98%) had elevated anxiety. However, we found the comorbidity of anxiety was lower than 12.43%, the international comorbidity of pregnant women having anxiety symptoms at various stages of pregnancy6,32. This could be because most of our participants were in their second trimester, previous studies have revealed that anxiety level are at their lowest in the second trimester32. Thus, we should pay more attention to antenatal stress and anxiety in pregnant women, and promote healthy lifestyles.

As the mobile internet develops, phone usage is rapid increasing and becoming a global problem21, which is very common in pregnant women26. Previous studies revealed that maternal women who more often used cell phone during pregnancy not only had an impact on maternal and new-born care practices20,33, but also lead to children behaviour abnormal at age seven34 and emotion and behaviour difficult at age eleven35. During all included variables, phone usage was the strongest risk factor for prenatal stress and anxiety. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report the association between phone usage during pregnancy and prenatal stress and anxiety. We also found that increased daily phone usage was positively correlated to an increased risk of prenatal stress and anxiety. If maternal women use phone >6 hours per day during pregnancy, the risk of prenatal stress and anxiety increased 2.43 and 2.62 times than not use phone, respectively. There are some explanations for our results: First, maternal women spend much time on mobile phone, limiting the time to do their daily work and resting21, which may influence the pregnant women’s mood. Second, most of pregnant women know that the electromagnetic radiation is harmful to adult’s and infant’s health26. It has been well documented that exposing to cell phone could lead to radio frequency electromagnetic field (RF-EMF)36. Moreover, Gao et al. found that mobile phone addiction (>4 hours/day) could increase the risk of anxiety of college students21. Either work requirement or addiction, more often using phone could increase the mood complexity of pregnant women.

In future pre-pregnancy health promotion, we should advise maternal women to limit the time spending on phone use, and broadcast excess RF- EMF exposure is harmful to human physical and mental health problems, fetuses or children would be more vulnerable to this potential influence, because neurological and organ systems is rapid development in early life and the extended exposure would be over the entire lifespan37,38.

Rushed lifestyles and gestational fatigue may lead to irregular sleep patterns, causing sleep deprivation, which can be harmful to pregnant women and infants39,40,41. Our study showed that pregnant women with poor sleep quality had higher levels of prenatal stress and anxiety, which was consistent with previous reports. In particular, previous studies reported that poor sleep quality was associated with prenatal depression41,42, stress27,41 and anxiety27. Okun et al.41 reported that pregnant women who sleep less than 7 hours per day may experience depressive symptoms. The biological mechanisms most associated with stress and anxiety was the joint stress-induced activation of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis and the progesterone (PROG) derived gamma-amino-butyric acid (GABA) ERGIC neurosteroids27, which has been implicated in reproductive mood disorders43,44. Previous studies suggested that maternal HPA axis responses to prenatal stress and anxiety were markedly suppressed in the second trimester27 and in late pregnancy45,46. Thus, it’s very important to promote the maternal women sleep quality during pregnancy, especially at the second and third trimester.

Household air pollution (HAP) arising from solid fuel use and meat cooking remains a global health threat28,29. Previous studies reported that exposure to HAP could have an impact on adverse birth outcomes, such as low birth weight47,48. To our knowledge, this is the first report focusing on the relationship between frequent cooking (≥3–5 times per week) during pregnancy and prenatal stress. Our results showed that not frequent cooking was negatively correlated to prenatal stress (OR = 0.65, 95%CI: 0.53, 0.80, P < 0.001). The majority of pregnant women know that cooking is one kind of household air pollution via the public platform and watching TV, which could increase maternal physical burden during pregnancy. Moreover, frequent cooking could increase the physically burden of pregnant women, especially who was with gestation reaction. In future pregnancy health care, we should advise pregnant women decrease the cooking times during pregnancy.

Interestingly, our study also showed that having pets during pregnancy was negatively correlated to prenatal anxiety (OR = 0.46, 95%CI: 0.26, 0.84, P = 0.011). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the relationship between having pets and maternal anxiety in pregnancy. The explanation for this results was that having pets could increase the life interesting and reduce the uncomfortableness of gestation. In addition, previous studies reported that exposure to pets, such as dogs or cats, could increase the resistance of immune system, and pregnant women could learn about this knowledge via internet, newspaper, et al. A meta-analysis reported that pregnant women exposed to household pets in the prenatal period were less likely to have an infant suffer from allergic diseases49. Havstad50 reported prenatal and postnatal pet exposure could result in lower IgE levels in very early life. Tun et al. found reduced streptococcal colonisation as a result of prenatal pet ownership may lower the risk of childhood metabolic and atopic disease51. With increasing reports of the beneficial effects of having pets at home, more and more households are getting pets. Although previous studies have revealed how beneficial pets are for pregnant women’s physical and psychological health, it is important to maintain a clean household and ensure all pets are up to date with their vaccinations.

Additionally, our study also discovered the relationship between having babies at home and prenatal stress, as far as we know, this is the first time this relationship has been studied by quantitative study. Our results showed that having babies at home could decrease the stress levels of maternal women, and there are no distinction during have one baby and ≥2 babies. These consisted with previous qualitative studies which have shown that women feel stressful if they are the first experience of motherhood52. First explanation for this is that first-time mothers were very concerned about the safety and wellbeing of their infants, and were very aware that they had responsibility for another life after delivery53. On the other hand, pregnant women who had no baby at home were concern about the new baby care after birth, because they are lack of confidence in themselves as new mothers to care for their baby. As a matter of fact, most women have very little opportunities to contact with babies and learn from others prior to becoming a mother52. At last, having a baby at home could increase the family’s happiness53. Thus, constant professional support during pregnancy is a perceived need for first- mother.

It is evident from our study that maternal lifestyles play an important role on prenatal stress and anxiety. It highlights the importance of pregnant women’s psychosocial health, assessing their risk factors and developing ways to improve their psychosocial resources to prevent antenatal stress and anxiety. Finally, our study also points to the need for greater research and clinical attention to antenatal stress and anxiety.

The key strength of our study as follow: First, to our knowledge, this is the first report of the relationship between phone usage, frequent cooking and having pets and prenatal maternal anxiety and stress. Second, this is the first report about the associations of various new lifestyles and prenatal stress and anxiety. In addition, there are several limitations in this study. In the cross-sectional study, prenatal stress and anxiety was not analysed in different trimesters because most participants were in their second trimester, which limited the study of prenatal stress and anxiety changes throughout the pregnancy. This will be considered in future studies. Second, because the data was collected from questionnaires, retrospective bias was inevitable. In future study, we could consider combine clinically diagnosed stress and anxiety disorders and self-reported symptoms. Moreover, we will increase the follow-up times to reduce the retrospective bias. In addition, we will do further studies because the evidences of reporting the associations of phone usage, frequent cooking, having pets and having babies at home and prenatal stress and anxiety are limited at present.

Conclusions

From this study, we found that parts of maternal lifestyles play a vital role on prenatal stress and anxiety levels, indicating the importance of balanced maternal lifestyles during pregnancy. Moreover, the results could assist healthcare professionals in prevention, early identification and treatment of prenatal stress and anxiety.

Materials and Methods

Ethical approval and informed consent

The study was reviewed and approved by the Guangxi Medical University Medical Ethics Committee (ID: 2015(028)). All patients consented to participate in the research, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Study design and population

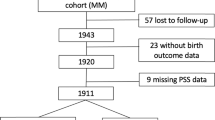

The cross-sectional study was based on the GBCS, an ongoing multicentre prospective cohort study in Guangxi, which aims to investigate pregnancy outcomes and the short and long-term health consequences of hereditary factors, environmental factors54 and psychological behavioural factors on children in the fast-paced society. 6,203 volunteers were recruited and followed-up from July 2015 until October 2016 in seven maternal & child health hospitals in Guangxi. In our present study, 1839 volunteers were recruited from GBCS at their prenatal examination between March and October in 2016. The inclusion criteria were the volunteers were between 18 and 45 years old, were born and lived in the study areas, had comprehensive ability to complete face-to-face interview questionnaires and had completed PSRS and SAS questionnaires. Excluding invalid questionnaires, 1547 were followed-up until they gave birth. After exclusions (abortion, stillbirth and birth defects), 1491 pregnant women were followed-up.

Data Collection

Participants were invited to complete three questionnaires: the base line questionnaire, PSRS and SAS. The base line questionnaire was used to collect sociodemographic information and lifestyle information. The PSRS55 and SAS56 were performed to assess the anxiety and stress status of the participants.

Basic demographic factors

Maternal age, ethnicity, education level, annual household income, profession, historic and present pregnancy information, such as whether they have regular menstruation or not and last menstrual period (LMP), gestational hypertension or gestational diabetes, et al. were collected using face-to-face questionnaires. Maternal and infant’s information was collected from the Guangxi Maternal and Child Health Information System.

Lifestyles during pregnancy

Lifestyles, such as phone usage, hours of daily phone usage, whether the participant had afternoon naps, self-reported sleep quality, whether or not frequent cooking, having pets and having babies at home, et al. were collected from face-to-face questionnaire.

Phone usage was defined as maternal women use phone time per day during pregnancy which was collected from questionnaires by self-reported. It was divided into three groups, not using phone, using phone time <6 hours per day and ≥6 hours per day. Self-reported sleep quality was defined as maternal women’s sleep quality during pregnancy, which was also collected from questionnaires by self-reported and was recorded as “bad, generally and good”. Frequent cooking was defined as pregnant women cook ≥3–5 times per week during antenatal period. Having babies at home was defined as pregnant women have one or more babies at home, the age of them was from 1 to 12 years old. According to the number of babies, we divided it into “not having baby, having one baby and ≥2 babies” groups.

PSRS

Antenatal stress was assessed with the PSRS55, a commonly used 30-item measure of stress in the antenatal period. The Chinese version was compiled and revised by Chen Chung-Hey and Pan Ying-Li and validated among pregnant women, with good psychometric properties22,57. This scale includes four stressors, including “Identify with a parent’s role”, “Concern about the health and safety of mother and children”, “Concern about the change of figure and activity” and “Else stressor”. PSRS is a 4- point Likert scale, from 0 (no stress) to 3 (severe stress). The total score is the mean of all items summed, with higher score indicating higher level of pregnancy stress. The total Cronbach’s α is 0.94.

SAS

The SAS56 was chosen because it was specifically developed to measure maternal anxiety. It effectively evaluates the participant’s mood over the previous week. Many scholars have used this scale to assess the mental health of pregnant women22,58,59. SAS is composed of 20 items, a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 (None) to 4 (Most of the time). It is mainly used to assess the frequency of the symptoms mentioned in the items. The item score is standardised according to the formula: standardised score equals to integer (1.25 × item score)59. The standardised score is used as an index of prenatal anxiety, and the cut-off value is 50. The standardised scores 50 - 59, 60 - 69 and ≥70 present mild, moderate and severe anxiety, respectively. The Cronbach’s α is 0.91.

Quality control

Investigations

All staff were master’s degree students of prophylactic medicine or clinical medicine. Before working, all investigators had completed unified training and simulated exercised. All of them were familiar with questionnaires and scales, understood the principles and announcements of the investigation and had mastered the unified methods and techniques required to guide subjects when they were completing the questionnaires.

After reviewing a great deal of literature, we modelled the research questionnaire on previous studies. The questionnaire was reviewed, modified and supplemented by relevant experts. Before the survey, we conducted pre-survey checks to discover all problems and revised the questionnaires accordingly.

Investigation process

We distributed the questionnaires and then collected them on time when participants completed. Investigators immediately checked and verified the integrity and validity of the questionnaires. To ensure the veracity of data, two independent workers completed the inputting process.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM). Frequencies were compared between groups by the χ2 test and were displayed as percentages (%). Ordinal multiple logistic regression analyses were used to examine the correlation between selected lifestyles and prenatal stress by calculating odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Binary logistic regression analyses were used to examine the association of selected lifestyles and prenatal anxiety, ORs and 95% CIs were also calculated. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

van Heyningen, T. et al. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety disorders amongst low-income pregnant women in urban South Africa: a cross-sectional study. Archives of women’s mental health 20, 765–775, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-017-0768-z (2017).

Latendresse, G. et al. Duration of Maternal Stress and Depression. Nursing Research 64, 331–341, https://doi.org/10.1097/nnr.0000000000000117 (2015).

Gilles, M. et al. Maternal hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) system activity and stress during pregnancy: Effects on gestational age and infant’s anthropometric measures at birth. Psychoneuroendocrinology https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.04.022 (2018).

Dole, N. Maternal Stress and Preterm Birth. American Journal of Epidemiology 157, 14–24, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwf176 (2003).

Andersson, L. et al. Point prevalence of psychiatric disorders during the second trimester of pregnancy: A population-based study. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 189, 148–154, https://doi.org/10.1067/mob.2003.336 (2003).

Dunkel Schetter, C. Psychological science on pregnancy: stress processes, biopsychosocial models, and emerging research issues. Annual review of psychology 62, 531–558, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.031809.130727 (2011).

Lobel, M. et al. Pregnancy-specific stress, prenatal health behaviors, and birth outcomes. Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association 27, 604–615, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013242 (2008).

Staneva, A., Bogossian, F., Pritchard, M. & Wittkowski, A. The effects of maternal depression, anxiety, and perceived stress during pregnancy on preterm birth: A systematic review. Women and birth: journal of the Australian College of Midwives 28, 179–193, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2015.02.003 (2015).

Hasanjanzadeh, P. & Faramarzi, M. Relationship between Maternal General and Specific-Pregnancy Stress, Anxiety, and Depression Symptoms and Pregnancy Outcome. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research: JCDR 11, Vc04–vc07, https://doi.org/10.7860/jcdr/2017/24352.9616 (2017).

de Weerth, C. & Buitelaar, J. K. Physiological stress reactivity in human pregnancy–a review. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 29, 295–312, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.10.005 (2005).

Glynn, L. M., Wadhwa, P. D., Dunkel-Schetter, C., Chicz-Demet, A. & Sandman, C. A. When stress happens matters: effects of earthquake timing on stress responsivity in pregnancy. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 184, 637–642, https://doi.org/10.1067/mob.2001.111066 (2001).

Phelan, A. L., DiBenedetto, M. R., Paul, I. M., Zhu, J. & Kjerulff, K. H. Psychosocial Stress During First Pregnancy Predicts Infant Health Outcomes in the First Postnatal Year. Maternal and child health journal 19, 2587–2597, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-015-1777-z (2015).

Silveira, M. L., Pekow, P. S., Dole, N., Markenson, G. & Chasan-Taber, L. Correlates of high perceived stress among pregnant Hispanic women in Western Massachusetts. Maternal and child health journal 17, 1138–1150, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-012-1106-8 (2013).

Gotlib, I. H., Whiffen, V. E., Mount, J. H., Milne K. & Cordy, N. I. Prevalence Rates and Demographic Characteristics Associated With Depression in Pregnancy and the Postpartum. Consullingand Clinical Psychology (1989).

Biaggi, A., Conroy, S., Pawlby, S. & Pariante, C. M. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. Journal of affective disorders 191, 62–77, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.014 (2016).

Roberts, S. C., Wilsnack, S. C., Foster, D. G. & Delucchi, K. L. Alcohol use before and during unwanted pregnancy. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research 38, 2844–2852, https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.12544 (2014).

Mariangela, F. Silveira et al. Secular trends in smoking during pregnancy according to income and ethnic group: four population-based perinatal surveys in a Brazilian city. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-201501012710.1136/bmjopen-2015-010127 (2016).

Hadley, C. et al. Food insecurity, stressful life events and symptoms of anxiety and depression in east Africa: evidence from the Gilgel Gibe growth and development study. Journal of epidemiology and community health 62, 980–986, https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2007.068460 (2008).

McDonald, S. W., Kingston, D., Bayrampour, H., Dolan, S. M. & Tough, S. C. Cumulative psychosocial stress, coping resources, and preterm birth. Archives of women’s mental health 17, 559–568, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-014-0436-5 (2014).

Alam, M., D’Este, C., Banwell, C. & Lokuge, K. The impact of mobile phone based messages on maternal and child healthcare behaviour: a retrospective cross-sectional survey in Bangladesh. BMC health services research 17, 434, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2361-6 (2017).

Gao, T. et al. The influence of alexithymia on mobile phone addiction: The role of depression, anxiety and stress. Journal of affective disorders 225, 761–766, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.020 (2018).

Li, G. et al. Relationship between prenatal maternal stress and sleep quality in Chinese pregnant women: the mediation effect of resilience. Sleep medicine 25, 8–12, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2016.02.015 (2016).

Bahreyni Toossi, M. H. et al. Exposure to mobile phone (900–1800 MHz) during pregnancy: tissue oxidative stress after childbirth. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine: the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet, 1–6 https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2017.1315657 (2017).

Ozorak, A. et al. Wi-Fi (2.45 GHz)- and mobile phone (900 and 1800 MHz)-induced risks on oxidative stress and elements in kidney and testis of rats during pregnancy and the development of offspring. Biological trace element research 156, 221–229, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-013-9836-z (2013).

Esmekaya, M. A. et al. Mutagenic and morphologic impacts of 1.8GHz radiofrequency radiation on human peripheral blood lymphocytes (hPBLs) and possible protective role of pre-treatment with Ginkgo biloba (EGb 761). The Science of the total environment 410–411, 59–64, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.09.036 (2011).

Birks, L. et al. Maternal cell phone use during pregnancy and child behavioral problems in five birth cohorts. Environment international 104, 122–131, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2017.03.024 (2017).

Crowley, S. K. et al. Blunted neuroactive steroid and HPA axis responses to stress are associated with reduced sleep quality and negative affect in pregnancy: a pilot study. Psychopharmacology 233, 1299–1310, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-016-4217-x (2016).

Yu, K. et al. Association of Solid Fuel Use With Risk of Cardiovascular and All-Cause Mortality in Rural China. Jama 319, 1351–1361, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.2151 (2018).

Wei, F. et al. Association between Chinese cooking oil fumes and sleep quality among a middle-aged Chinese population. Environmental pollution 227, 543–551, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.05.018 (2017).

Mohsen Janghorbani, S. Y. H., Lam, T. H. & Janus, E. D. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol use: a population based study in Hong Kong (2002).

DeVido, J., Bogunovic, O. & Weiss, R. D. Alcohol use disorders in pregnancy. Harvard review of psychiatry 23, 112–121, https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000070 (2015).

Lee, A. M. et al. Prevalence, Course, and Risk Factors for Antenatal Anxiety and Depression. Obstetrics & Gynecology (2007).

Constant, D., Harries, J., Daskilewicz, K., Myer, L. & Gemzell-Danielsson, K. Is self-assessment of medical abortion using a low-sensitivity pregnancy test combined with a checklist and phone text messages feasible in South African primary healthcare settings? A randomized trial. PloS one 12, e0179600, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179600 (2017).

Divan, H. A., Kheifets, L., Obel, C. & Olsen, J. Cell phone use and behavioural problems in young children. Journal of epidemiology and community health 66, 524–529, https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2010.115402 (2012).

Sudan, M., Olsen, J., Arah, O. A., Obel, C. & Kheifets, L. Prospective cohort analysis of cellphone use and emotional and behavioural difficulties in children. Journal of epidemiology and community health https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2016-207419 (2016).

Cardis, E. et al. Estimation of RF energy absorbed in the brain from mobile phones in the Interphone Study. Occupational and environmental medicine 68, 686–693, https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2011-100065 (2011).

Leung, S. et al. Effects of 2G and 3G mobile phones on performance and electrophysiology in adolescents, young adults and older adults. Clinical neurophysiology: official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology 122, 2203–2216, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2011.04.006 (2011).

Kheifets, L., Repacholi, M., Saunders, R. & van Deventer, E. The sensitivity of children to electromagnetic fields. Pediatrics 116, e303–313, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-2541 (2005).

Abeysena, C., Jayawardana, P. & R., D. A. S. Maternal sleep deprivation is a risk factor for small for gestational age: a cohort study. The Australian & New Zealand journal of obstetrics & gynaecology 49, 382–387, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-828X.2009.01010.x (2009).

Micheli, K. et al. Sleep patterns in late pregnancy and risk of preterm birth and fetal growth restriction. Epidemiology 22, 738–744, https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e31822546fd (2011).

Okun, M. L. et al. Prevalence of sleep deficiency in early gestation and its associations with stress and depressive symptoms. Journal of women’s health 22, 1028–1037, https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2013.4331 (2013).

Skouteris, H., Germano, C., Wertheim, E. H., Paxton, S. J. & Milgrom, J. Sleep quality and depression during pregnancy: a prospective study. Journal of sleep research 17, 217–220, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00655.x (2008).

Segebladh, B. et al. Allopregnanolone serum concentrations and diurnal cortisol secretion in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Archives of women’s mental health 16, 131–137, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-013-0327-1 (2013).

Girdler, S. S., Straneva, P. A., Light, K. C., Pedersen, C. A. & Morrow, A. L. Allopregnanolone Levels and Reactivity to Mental Stress in Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. Society of Biological Psychiatry (2001).

Brunton, P. J. & Russell, J. A. The expectant brain: adapting for motherhood. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 9, 11–25, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2280 (2008).

Christian, L. M. Physiological reactivity to psychological stress in human pregnancy: current knowledge and future directions. Progress in neurobiology 99, 106–116, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.07.003 (2012).

Khan, M. N., C. Z. B. N., Mofizul Islam, M., Islam, M. R. & Rahman, M. M. Household air pollution from cooking and risk of adverse health and birth outcomes in Bangladesh: a nationwide population-based study. Environmental health: a global access science source 16, 57, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-017-0272-y (2017).

Lee, P. C., Roberts, J. M., Catov, J. M., Talbott, E. O. & Ritz, B. First trimester exposure to ambient air pollution, pregnancy complications and adverse birth outcomes in Allegheny County, PA. Maternal and child health journal 17, 545–555, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-012-1028-5 (2013).

Lodge, C. J. et al. Perinatal cat and dog exposure and the risk of asthma and allergy in the urban environment: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Clinical & developmental immunology 2012, 176484, https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/176484 (2012).

Havstad, S. et al. Effect of prenatal indoor pet exposure on the trajectory of total IgE levels in early childhood. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 128, 880–885 e884, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2011.06.039 (2011).

Tun, H. M. et al. Exposure to household furry pets influences the gut microbiota of infant at 3-4 months following various birth scenarios. Microbiome 5, 40, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-017-0254-x (2017).

Forster, D. A. et al. The early postnatal period: exploring women’s views, expectations and experiences of care using focus groups in Victoria, Australia. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 8, 27, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-8-27 (2008).

Ong, S. F. et al. Postnatal experiences and support needs of first-time mothers in Singapore: a descriptive qualitative study. Midwifery 30, 772–778, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2013.09.004 (2014).

Jiang, C. et al. The effect of pre-pregnancy hair dye exposure on infant birth weight: a nested case-control study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 18 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1782-5 (2018).

Li, Y., Zeng, Y., Zhu, W., Cui, Y. & Li, J. Path model of antenatal stress and depressive symptoms among Chinese primipara in late pregnancy. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 16, 180, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0972-2 (2016).

Zung, W. W. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Official Journal of The Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine (1971).

Zeng, Y., Cui, Y. & Li, J. Prevalence and predictors of antenatal depressive symptoms among Chinese women in their third trimester: a cross-sectional survey. BMC psychiatry 15, 66, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0452-7 (2015).

Glynn, L. M., Schetter, C. D., Hobel, C. J. & Sandman, C. A. Pattern of perceived stress and anxiety in pregnancy predicts preterm birth. Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association 27, 43–51, https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.43 (2008).

Liu, L., Xu, N. & Wang, L. Moderating role of self-efficacy on the associations of social support with depressive and anxiety symptoms in Chinese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment 13, 2141–2150, https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S137233 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to all the participants in our study and sincerely thank the department of Maternal and Child Health Services of The Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Health and Family Planning Commission. This study was funded by the Fok Ying Tong Education Foundation (141118), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81370857), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Province (2013GXNSFFA019002) and Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Province (2017GXNSFGA198003). We sincerely thank the Editor professor Yi-Hua Chen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Y. and Q.H. contributed to the design of the study and Q.H. drafted the initial manuscript. S.L., Q.H. and C.J. completed the statistical analysis. S.L., C.J., Y.H., L.H. and J.Y. collected data and completed the data input under the supervision of X.Y. Z.P. and T.T. provided scientific advice on the process of data acquisition and made data interpretation. Q.W., Y.J., H.Z., M.L., Z.M. and X.Y. completed the design of cohort study. Q.H., C.J., L.H., C.L. and X.Y. contributed in reviewing the final manuscript. All authors contributed to drafting the paper and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, Q., Li, S., Jiang, C. et al. The associations between maternal lifestyles and antenatal stress and anxiety in Chinese pregnant women: A cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 8, 10771 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28974-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28974-x

This article is cited by

-

Maternal performance after childbirth and its predictors: a cross sectional study

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2024)

-

Path analysis of influencing factors for maternal antenatal depression in the third trimester

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Resilience mediates the effect of self-efficacy on symptoms of prenatal anxiety among pregnant women: a nationwide smartphone cross-sectional study in China

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2021)

-

Factors associated with violence against women in a representative sample of the Lebanese population: results of a cross-sectional study

Archives of Women's Mental Health (2021)

-

Cortisol and DHEA-S levels in pregnant women with severe anxiety

BMC Psychiatry (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.