Abstract

Objective

To determine whether perceived stress is associated with preterm birth (PTB) and to investigate racial differences in stress and PTB.

Study design

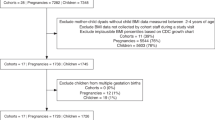

A secondary analysis of a prospective cohort study of 1911 women with singleton pregnancies examined responses to psychosocial stress questionnaires at 16–20 weeks of gestation.

Results

High perceived stress (19%) and PTB (10.8%) were prevalent in our sample (62% non-Hispanic Black). Women with PTB were more likely to be Black, have chronic hypertension (cHTN), pregestational diabetes, and higher BMI. Women with high perceived stress had more PTBs than those with lower stress (15.2% vs. 9.8%), and stress was associated with higher odds of PTB (aOR: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.09–2.19).

Conclusion

The significant association between high perceived stress and PTB suggests that prenatal interventions to reduce maternal stress could improve the mental health of pregnant women and may result in reduced rates of PTB.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Matthews TJ, MacDorman MF, Thoma ME. Infant mortality statistics from the 2013 period linked birth/infant death data set. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2015;64:1–30.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Behrman RE, Butler AS, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2007 PMID: 20669423.

Boyd R, Lindo E, Weeks L, McLemore MR. “On Racism: A New Standard For Publishing On Racial Health Inequities”, Health Affairs Blog, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1377/hblog20200630.939347.

Rini CK, Dunkel-Schetter C, Wadhwa PD, Sandman CA. Psychological adaptation and birth outcomes: the role of personal resources, stress, and sociocultural context in pregnancy. Health Psychol. 1999;18:333–45.

Copper RL, Goldenberg RL, Das A, Elder N, Swain M, Norman G, et al. The preterm prediction study: maternal stress is associated with spontaneous preterm birth at less than thirty-five weeks’ gestation. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1286–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70042-x.

Dole N, Savitz DA, Hertz-Picciotto I, Siega-Riz AM, McMahon MJ, Buekens P. Maternal stress and preterm birth. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:14–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwf176.

Rondó PH, Ferreira RF, Nogueira F, Ribeiro MC, Lobert H, Artes R. Maternal psychological stress and distress as predictors of low birth weight, prematurity and intrauterine growth retardation. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:266–72. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601526.

Guendelman S, Kosa JL, Pearl M, Graham S, Kharrazi M. Exploring the relationship of second-trimester corticotropin releasing hormone, chronic stress and preterm delivery. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21:788–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767050802379031.

Levine TA, Alderdice FA, Grunau RE, McAuliffe FM. Prenatal stress and hemodynamics in pregnancy: a systematic review. Arch Women’s Ment Health. 2016;19:721–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-016-0645-1.

Ruiz RJ, Gennaro S, O’Connor C, Dwivedi A, Gibeau A, Keshinover T, et al. CRH as a predictor of preterm birth in minority women. Biol Res Nurs. 2016;18:316–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1099800415611248.

Arbour MW, Corwin EJ, Salsberry PJ, Atkins M. Racial differences in the health of childbearing-aged women. MCN Am J Matern/Child Nurs. 2012;37:262–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMC.0b013e31824b544e.

Khashan AS, McNamee R, Abel KM, Mortensen PB, Kenny LC, Pedersen MG, et al. Rates of preterm birth following antenatal maternal exposure to severe life events: a population-based cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:429–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/den418.

Kramer MR, Hogue CJ, Dunlop AL, Menon R. Preconceptional stress and racial disparities in preterm birth: An overview. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90:1307–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01136.x.

Kramer MS, Lydon J, Seguin L, Goulet L, Kahn SR, McNamara H, et al. Stress pathways to spontaneous preterm birth: The role of stressors, psychological distress, and stress hormones. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:1319–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwp061.

Wheeler S, Maxson P, Truong T, Swamy G. Psychosocial stress and preterm birth: the impact of parity and race. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22:1430–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2523-0.

Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Ananth C. Trends in spontaneous and indicated preterm delivery among singleton gestations in the United States, 2005-2012. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:1069–74.

Wei S, Fraser W, Luo Z. Inflammatory cytokines and spontaneous preterm birth in asymptomatic women: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:393–401.

Kramer MS, Lydon J, Goulet L, Kahn S, Dahhou M, Platt RW, et al. Maternal stress/distress, hormonal pathways and spontaneous preterm birth. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013;27:237–46.

DiGiulio DB, Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Costello EK, Lyell DJ, Robaczewska A, et al. Temporal and spatial variation of the human microbiota during pregnancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112:11060–5.

Christian LM. Psychoneuroimmunology in pregnancy: Immune pathways linking stress with maternal health, adverse birth outcomes, and fetal development. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:350–61.

Dunkel Schetter C. Psychological science on pregnancy: stress processes, biopsychosocial models, and emerging research issues. Annu Rev Psychol. 2011;62:531–58.

Wadhwa PD, Entringer S, Buss C, Lu MC. The contribution of maternal stress to preterm birth: issues and considerations. Clin Perinatol. 2011;38:351–84.

Coussons-Read ME, Lobel M, Carey JC, Kreither MO, D’Anna K, Argys L, et al. The occurrence of preterm delivery is linked to pregnancy-specific distress and elevated inflammatory markers across gestation. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:650–9.

Peterson GF, Espel EV, Davis EP, Sandman CA, Glynn LM. Characterizing prenatal maternal distress with unique prenatal cortisol trajectories. Health Psychol. 2020;39:1013–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0001018.

Sandman CA. Prenatal CRH: an integrating signal of fetal distress. Dev Psychopathol. 2018;30:941–52.

Ramos IF, Guardino CM, Mansolf M, Glynn LM, Sandman CA, Hobel CJ, et al. Pregnancy anxiety predicts shorter gestation in Latina and non-Latina white women: the role of placental corticotrophin-releasing hormone. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;99:166–73.

Swales DA, Grande LA, Wing DA, Edelmann M, Glynn LM, Sandman C, et al. Can placental corticotropin-releasing hormone inform timing of antenatal corticosteroid administration? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:443–50.

Hoffman MC, Mazzoni SE, Wagner BD, Laudenslager ML, Ross RG. Measures of maternal stress and mood in relation to preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:545–52.

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK, Drake P. Births: Final data for 2018. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 68 no 13. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2019. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_13-508.pdf.

Johnson S, Bobb J, Ito K, Johnson S, McAlexander T, Ross Z, et al. Ambient fine particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, and preterm birth in New York City. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124:1283–90.

Luke S, Salihu HM, Alio AP, Mbah AK, Jeffers D, Berry EL, et al. Risk factors for major antenatal depression among low-income African American women. J Women’s Health. 2009;18:1841–6.

Melville JL, Gavin A, Guo Y, Fan M, Katon WJ. Depressive disorders during pregnancy: prevalence and risk factors in a large urban sample. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1064–70.

Blumenshine P, Egerter S, Barclay CJ, Cubbin C, Braveman PA. Socioeconomic disparities in adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39:263–72.

Gennaro S, Shults J, Garry DJ. Stress and preterm labor and birth in black women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2008;37:538–45.

Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, Washington AE. Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: Prevalence and determinants. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:335–43.

Jallo N, Elswick R, Kinser P, Masho S, Price S, Svikis D. Prevalence and predictors of depressive symptoms in pregnant African American women. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2015;36:860–9.

Canady RB, Bullen BL, Holzman C, Broman C, Tian Y. Discrimination and symptoms of depression in pregnancy among African American and White women. Women’s Health Issues. 2008;18:292–300.

Grobman WA, Parker CB, Willinger M, Wing DA, Silver RM, Wapner RJ, et al. Racial Disparities in Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes and Psychosocial Stress. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:328–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002441.

Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, Melville JL, Iyengar S, Katon WJ. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1012–24.

Louis JM, Menard MK, Gee RE. Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:690–4.

Elovitz MA, Gajer P, Riis V, Brown AG, Humphrys MS, Holm JB, et al. Cervicovaginal microbiota and local immune response modulate the risk of spontaneous preterm delivery. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1305. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09285-9.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–96.

Solivan AE, Xiong X, Harville EW, Buekens P. Measurement of perceived stress among pregnant women: a comparison of two different instruments. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:1910–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-015-1710-5.

Natamba BK, Achan J, Arbach A, Oyok TO, Ghosh S, Mehta S, et al. Reliability and validity of the center for epidemiologic studies-depression scale in screening for depression among HIV-infected and -uninfected pregnant women attending antenatal services in northern Uganda: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:303. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-014-0303-y.

Burris HH, Riis VM, Schmidt I, Gerson KD, Brown A, Elovitz MA. Maternal stress, low cervicovaginal β-defensin, and spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100092.

Silveira ML, Pekow PS, Dole N, Markenson G, Chasan-Taber L. Correlates of high perceived stress among pregnant Hispanic women in western Massachusetts. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17:1138–50.

Hobel CJ, Goldstein A, Barrett ES. Psychosocial stress and pregnancy outcome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51:333–48.

Liu L, Setse R, Grogan R, Powe NR, Nicholson WK. The effect of depression symptoms and social support on black-white differences in health-related quality of life in early pregnancy: the health status in pregnancy (HIP) study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:125.

Forde A, Crookes D, Suglia S, Demmer R. The weathering hypothesis as an explanation for racial disparities in health: a systematic review. Ann Epidemiol. 2019;33:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.02.011.

Geronimus AT. The weathering hypothesis and the health of African-American women and infants: evidence and speculations. Ethnicity Dis Summer. 1992;2:207–21.

Holzman C, Eyster J, Kleyn M, Messer LC, Kaufman JS, Laraia BA, et al. Maternal weathering and risk of preterm delivery. Am J Pub Health. 2009;99:1864–71. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.151589.

Witt WP, Wisk LE, Cheng ER, Hampton JM, Hagen EW. Preconception mental health predicts pregnancy complications and adverse birth outcomes: a national population-based study. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:1525–41.

Clout D, Brown R. Sociodemographic, pregnancy, obstetric, and postnatal predictors of postpartum stress, anxiety and depression in new mothers. J Affect Disord. 2015;188:60–7.

Collins JW, David RJ, Symons R, Handler A, Wall SN, Dwyer L. Low-Income African-American mothers’ perception of exposure to racial discrimination and infant birth weight. Epidemiology. 2000;11:337–9.

Borders AE, Wolfe K, Qadir S, Kim KY, Holl J, Grobman W. Racial/ethnic differences in self-reported and biologic measures of chronic stress in pregnancy. J Perinatol. 2015;35:580–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2015.18.

Chow A, Dharma C, Chen E, Mandhane PJ, Turvey SE, Elliot SJ, et al. Trajectories of depressive symptoms and perceived stress from pregnancy to the postnatal period among Canadian women: impact of employment and immigration. Am J Public Health. 2019;109:S197–204. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304624.

ACOG Committee Opinion No. 757: Screening for Perinatal Depression, Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2018;5:e208–e212. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002927

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SLK: conceptualization, writing—original draft, review, and editing. VMR: data curation, investigation, project administration, and writing—original draft. CM: formal analysis, investigation, and methodology. MAE: conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision, writing—review and editing. HHB: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kornfield, S.L., Riis, V.M., McCarthy, C. et al. Maternal perceived stress and the increased risk of preterm birth in a majority non-Hispanic Black pregnancy cohort. J Perinatol 42, 708–713 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01186-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01186-4

This article is cited by

-

Extracellular vesicles are dynamic regulators of maternal glucose homeostasis during pregnancy

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Depression screening may not capture significant sources of prenatal stress for Black women

Archives of Women's Mental Health (2023)

-

Maternal stress and early childhood BMI among US children from the Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) program

Pediatric Research (2023)