Abstract

Naltrexone reduces drinking among individuals with alcohol use disorders (AUDs), but it is not effective for everyone. Variability in its effects on reward-related brain activation, genetic variation, and/or cigarette smoking may account for this mixed response profile. This randomized clinical trial tested the effects of naltrexone on drinking and alcohol cue-elicited brain activation, evaluated whether OPRM1 A118G genotype or smoking moderated these effects, and explored whether the effects of medication on cue-elicited activation predicted subsequent drinking. One hundred and fifty-two treatment-seeking individuals with alcohol dependence, half preselected to carry at least one A118G G (Asp) allele, were randomized to naltrexone (50 mg) or placebo for 16 weeks and administered an fMRI alcohol cue reactivity task at baseline and after 2 weeks of treatment. Naltrexone, relative to placebo, significantly reduced alcohol cue-elicited activation of the right ventral striatum (VS) between baseline and week 2 and reduced heavy drinking over 16 weeks. OPRM1 genotype did not significantly moderate these effects, but G-allele carriers who received naltrexone had an accelerated return to heavy drinking after medication was stopped. Smoking moderated the effects of medication on drinking, such that naltrexone was superior to placebo only among smokers. The degree of reduction in right VS activation between scans interacted with medication in predicting subsequent drinking, such that individuals with greater reduction in activation who received naltrexone, but not placebo, experienced the least heavy drinking during the following 14 weeks. These data replicate previous findings that naltrexone reduces heavy drinking and reward-related brain activation among treatment-seeking individuals with AUDs, and indicate that smoking and the magnitude of reduction in cue-elicited brain activation may predict treatment response.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The μ-opioid antagonist naltrexone (NTX) reduces heavy drinking among individuals with alcohol use disorders (AUDs; Jonas et al, 2014), but not everyone responds, perhaps due to individual variation in its mechanism of action. Specifically, NTX efficacy may be moderated by variation in the μ-opioid receptor gene (OPRM1), variability in its effects on reward-related brain activation, or individuals’ smoking status. The present study evaluated each of these factors as a predictor of NTX response.

There is mixed evidence regarding the influence of a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in OPRM1, A118G (Asn40Asp; rs1799971), in moderating NTX efficacy. Several initial randomized clinical trials (RCTs; Anton et al, 2008; Chamorro et al, 2012; Oslin et al, 2003), including a post hoc analysis of the COMBINE study (Anton et al, 2008), reported greater NTX efficacy among individuals who carried the A118G G (Asp) allele, which ~25% of Caucasians and 40% of Asians carry and which has been associated with increased β-endorphin-binding affinity for μ-opioid receptors (Bond et al, 1998). However, three subsequent RCTs (Coller et al, 2011; Gelernter et al, 2007; Oslin et al, 2015), including one that prospectively genotyped subjects before medication randomization to increase G-allele carrier enrollment, have found no such pharmacogenetic effect, although the Oslin study also reported no main effect of NTX, allowing the possibility that enhanced placebo response may have obscured a pharmacogenetic effect. Thus, the effects of A118G genotype on NTX response remain debatable.

There is stronger evidence from neuroimaging studies that NTX reduces alcohol cue-elicited activation of reward-related brain areas. We previously reported that NTX (50 mg, 7 days), relative to placebo, reduced cue-elicited activation of the ventral striatum (VS), medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC; Myrick et al, 2008). Another group found that extended release NTX (XR-NTX; 380-mg injection, 14 days), relative to placebo, reduced cue-elicited OFC, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and inferior frontal gyrus activation (Lukas et al, 2013). Independent of NTX, the A118G G-allele has been associated with greater alcohol cue-elicited activation (Bach et al, 2015; Filbey et al, 2008; Ray et al, 2014) and enhanced striatal dopamine response to intravenous ethanol (Ramchandani et al, 2011), suggesting that OPRM1 genotype might moderate the effects of NTX on this phenotype; however, G-allele carrier sample sizes have been small. Prospectively genotyped studies with more G-allele carriers have reported little evidence of an interaction between A118G genotype and NTX (50 mg, 5–7 days) on cue-elicited midbrain, VS, mPFC, ACC, OFC, insula, or amygdala activation (Schacht et al, 2013c; Ziauddeen et al, 2016), or on global binding of the selective μ-opioid agonist [11(C)]-carfentanil (Weerts et al, 2013). However, overall, neuroimaging studies of NTX and OPRM1 genotype have primarily enrolled non-treatment seekers and have largely failed to include baseline scans, leaving open the possibility that reported differences between medication and/or OPRM1 groups are pre-existing or do not extend to treatment-seeking subjects, whose AUDs are more severe (Rohn et al, 2017).

Independent of OPRM1 genotype, there is growing interest in whether cue-elicited brain activation may predict response to NTX or other pharmacotherapies (Courtney et al, 2016). For NTX, this phenotype might provide insight into a debate about whether abstinence early in treatment is particularly beneficial. Subjects with more lead-in abstinence respond best to XR-NTX (Garbutt et al, 2005; O'Malley et al, 2007), and COMBINE subjects with abstinent drinking goals, irrespective of medication, had better outcomes (Bujarski et al, 2013). Conversely, other studies have suggested that NTX is less effective when abstinence is promoted (Krystal et al, 2001), or that it should be administered specifically to actively drinking patients, so that its effects on craving- and/or alcohol-induced stimulation encourage extinction of these responses (Heinala et al, 2001; Sinclair, 2001). The analysis of the effects of NTX on cue-elicited activation among subjects with and without early abstinence could help resolve this dilemma. In the large German PREDICT study (modeled after COMBINE), subjects with greater baseline VS activation who subsequently received NTX (50 mg) had a longer time to relapse (Mann et al, 2014), and greater baseline VS and OFC activation after 2 weeks of treatment with NTX, acamprosate, or placebo was associated with shorter time to first relapse (Reinhard et al, 2015). However, PREDICT reported no medication effects on cue-elicited activation, leaving open the question of whether the effects of NTX on this phenotype might predict treatment response.

Cigarette smoking status may also moderate the effects of NTX. Nicotine dependence is twice as prevalent (45%) among alcohol-dependent individuals as in the general population (Grant et al, 2004). Studies of NTX for smoking cessation among heavy-drinking smokers have suggested that NTX reduces drinking in this subgroup (Fridberg et al, 2014; King et al, 2009; O'Malley et al, 2009). Most importantly, re-analysis of the COMBINE study suggested that NTX, relative to placebo, reduced heavy drinking only among smokers (Fucito et al, 2012). However, no other NTX RCT has yet analyzed this effect.

To further evaluate these potential predictors of NTX response, we conducted an RCT in which treatment-seeking individuals with AUDs were prospectively genotyped for the A118G SNP, randomized to NTX or placebo, and administered an fMRI alcohol cue reactivity paradigm at baseline and after 2 weeks of treatment. We focused on the effects of medication, genotype, and smoking on drinking and cue-elicited VS activation. The study had five hypotheses as follows: (1) NTX, relative to placebo, would reduce cue-elicited VS activation over 2 weeks and heavy drinking over 16 weeks; these effects would be greatest among (2) A118G G-allele carriers and (3) cigarette smokers; (4) NTX would reduce cue-elicited activation more among individuals who abstained from drinking between scans and; (5) greater reduction in VS activation would predict less subsequent heavy drinking among NTX-treated subjects.

Materials and methods

Overview

The study was a 16-week RCT (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00920829). The Medical University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board approved all procedures, and all subjects provided informed consent before participation. The study consisted of an initial assessment session, a baseline visit, and nine follow-up visits. fMRI scans were conducted at baseline and the second follow-up (week 2). At initial assessment, subjects completed a variety of self-report measures, including the Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale (OCDS; Anton et al, 1996) and Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS; Skinner and Allen, 1982), and provided a blood sample for A118G genotyping. As A-allele homozygotes were, as expected, more common, all G-allele carriers who met inclusion/exclusion criteria and approximately one of every three A-allele homozygotes were selected for participation. Typically, after an eligible G-allele carrier presented for assessment, the next eligible A-allele homozygote similar in sex and age to the G-allele carrier was selected.

Subjects

Subjects were recruited via media advertisements and clinical referrals, and were required to be ages 18–70; self-identify as Caucasian or Asian (secondary to low G-allele frequency among individuals of African descent); report heavy drinking (at least five/four standard drinks per day for men/women) on at least 50% of the days in the 90 days before assessment; and meet the DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, revised 4th edition) diagnostic criteria for Alcohol Dependence, as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (First et al, 2002). Subjects who reported cocaine or marijuana use in the 90 days before assessment were included, as long as they did not meet the DSM-IV criteria for dependence on either substance or any other except nicotine, and had a negative urine drug screen upon medication randomization. Exclusion criteria were as follows: current psychotropic medication use other than antidepressants (for which a stable dose for at least one month was required); current DSM-IV Axis I diagnosis or suicidal/homicidal ideation; history of significant medical illness; liver enzyme (ALT or AST) levels greater than three times the upper normal limit; and past-month NTX, disulfiram, or acamprosate use. Female subjects could not be pregnant or nursing.

The effect size for the A118G by medication interaction on heavy drinking from the COMBINE study (Anton et al, 2008) indicated that 40 subjects per medication/genotype group (N=160) would yield 80% power to detect this interaction. One hundred and fifty-two individuals were ultimately selected for participation and randomized to medication (Figure 1). Six subjects were deemed non-evaluable (eg, study protocol violations), leaving 146 evaluable subjects for the drinking outcomes. Of these subjects, 15 were not scanned (14 had MRI contraindications (eg, implanted metal, claustrophobia, and obesity) and 1 had a scheduling conflict) and 5 dropped out before week 2. This left 126 evaluable subjects who were scanned twice, of whom 10 were excluded due to motion artifacts during one or both scans, leaving 116 subjects with usable imaging data. Medication/genotype groups did not significantly differ in demographic characteristics, quantity/frequency of baseline drinking, the number of days between medication randomization and the subject’s last drink, or dependence severity (Table 1). In addition, there were no significant differences in demographic, drinking, or severity variables between subjects with vs without usable imaging data (Table 2).

CONSORT diagram of subject flow through the study.

Genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Gentra Puragene Blood Kit; Qiagen, Valencia, CA). After PCR amplification, A118G genotype was determined with a Taqman 5′ nuclease assay, using allele-specific probes (catalog no. C8950074, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and three known controls for each genotype.

Randomization and Intervention

Subjects were required to maintain abstinence for at least 4 days before medication randomization; those who were concerned that alcohol withdrawal symptoms would preclude this length of abstinence (n=17) were first treated with a lorazepam taper, with the last dose consumed at least 1 day before randomization. Subjects were then urn randomized (Stout et al, 1994) to receive NTX (25 mg for 2 days, then 50 mg thereafter) or placebo for 16 weeks. Randomization was stratified by A118G genotype, with the following urn variables balanced across medication groups: gender, smoking status (non-smoker vs smoker, defined as ⩾10 cigarettes per day), recent cocaine use, current antidepressant use, and AUD family history, defined as one or more first-degree relatives who the subject reported had a problem with alcohol. Study medications were identically over-encapsulated with 100 mg of riboflavin and distributed in labeled blister packs. Subjects and investigators were blind to both genotype and medication assignment. After randomization, subjects returned at weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 16, at which time all received medical management (MM) sessions (Pettinati et al, 2005), consisting of brief (15–20 min) interaction with a clinician who provided education and supportive advice aimed to enhance treatment adherence.

Assessment

During MM sessions, daily drinking since the last visit was assessed with the researcher-administered, calendar-based timeline follow-back (TLFB) interview (Sobell and Sobell, 1992), and the adverse effects of medication were assessed with the Systematic Assessment for Treatment Emergent Events (SAFTEE; Johnson et al, 2005). The number of cigarettes subjects smoked each day at baseline, week 8, and week 16 was assessed with the Addiction Severity Index (McLellan et al, 1980). Subjects who dropped out after randomization were compensated ($50) to return at week 16 to provide missing drinking data. Forty subjects ultimately dropped out, at similar rates across medication/genotype groups, but the full drinking data were available on 130 of 146 (89%) evaluable subjects and on 109 of 116 (94%) subjects with usable imaging data. To evaluate stability of response, the TLFB was administered again at 4 weeks (phone assessment), and at paid ($50) assessments at 12 and 24 weeks after the end of the 16-week medication period.

Adherence

Urine samples were collected at baseline and each of the nine study visits. Adherence was assessed with a fluorometric assay based on standard curves of weighed-in riboflavin (Anton, 1996). Samples were considered adherent if the urinary riboflavin value was ⩾1000 ng/ml or had doubled from baseline. In addition, subjects returned their blister packs at each study visit, and the pills taken since the last visit were counted.

fMRI Scans

Subjects were scanned at baseline (immediately before ingesting the first medication dose) and after at least 2 weeks of medication, with the majority conducted at week 2. To accommodate subject schedules while maximizing retention, three subjects were scanned at week 3 and one at week 4; however, the amount of time between scans did not significantly differ between groups. Scan procedures were identical to those previously published (Schacht et al, 2013b). Briefly, subjects were first breathalyzed and assessed for alcohol withdrawal with the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol-Revised (CIWA-Ar; Sullivan et al, 1989); no subject had a breath alcohol content >0 or a CIWA-Ar score >3. Subsequently, subjects were positioned in the scanner, and a high-resolution anatomical image was acquired. Subjects then completed a 12-m-long task during which they passively viewed pseudorandomly interspersed blocks of alcoholic beverage images (ALC; equally distributed between beer, wine, and liquor), non-alcoholic beverage images (BEV), blurred versions of these images that served as visual controls, and a fixation cross. Each 24-s-long block comprised only one image type and was followed by a 6-s period during which subjects were instructed to rate their urge for alcohol at that moment. Images were selected from a normative set (Stritzke et al, 2004), supplemented with images from advertisements, and matched for intensity, color, and complexity. Because subjects were treatment-seeking, they were not administered a sip of alcohol before viewing the images, unlike some past versions of this task.

Image Acquisition and Pre-Processing

Functional images were acquired with a gradient echo, echo-planar imaging sequence on a Siemens (Munich, Germany) TIM Trio 3 T scanner. Acquisition parameters were: repetition/echo times: 2200/35 ms; 328 volumes; flip angle: 90°; field of view: 192 mm; matrix: 64 × 64; voxel size: 3.0 × 3.0 mm; and 36 contiguous 3.0-mm-thick axial slices. Using FEAT v6.00, part of FSL (Oxford Centre for Functional MRI of the Brain, Oxford, UK; Smith et al, 2004), functional images were realigned to the middle volume, high-pass filtered (period=240 s), and spatially smoothed (8-mm full width at half maximum Gaussian kernel). Subjects with >2 mm/2° of translational/rotational movement during either scan (n=10) were excluded from analysis. Each subject’s functional images were then registered to his/her high-resolution anatomical image, and the 12 degree-of-freedom affine transformations between these images and the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) 152-brain-average template were calculated.

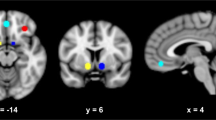

The average percentage change of the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal between ALC and BEV blocks (ie, ALC vs BEV percent signal change) was then extracted from two anatomically defined regions of interest (ROIs): right and left VS. We focused on the VS for four reasons: (1) VS is the region most consistently activated by alcohol cues, and this activation has repeatedly been associated with alcohol craving and AUD severity (Schacht et al, 2013a); (2) cue-elicited VS activation has good within-subject stability, suggesting it would be sensitive to intervention (Schacht et al, 2011); (3) NTX reduces this activation among non-treatment seekers (Myrick et al, 2008); and (4) PREDICT indicated that VS activation, relative to ACC/mPFC and OFC, was the strongest brain-based relapse predictor (Reinhard et al, 2015). ROIs were defined a priori as 6-mm-radius spheres centered at [−12 6 −9] (left VS) and [12 6 −9] (right VS) in MNI space, and were reverse-registered from the MNI-152 image to each subject’s anatomical image.

Statistical Analysis

A series of linear mixed models with unstructured variance/covariance matrices (SPSS 22, IBM, Armonk, NY) was used to evaluate the five primary hypotheses. For both the drinking and imaging outcomes, the primary model evaluated included a within-subject factor for time, between-subject factors for medication and A118G genotype, and all interactions of these factors. Subsequent hypothesis-driven analyses added between-subject factors for smoking status and, for the imaging outcomes, abstinence (any drinking vs complete abstinence between baseline and week 2), to test whether these factors moderated the effects of medication. Smoking was also evaluated as a continuous variable (number of cigarettes per day at baseline), and the effects of medication on smoking during the study were explored as well. Evaluation of baseline covariates found that the number of days between medication randomization and a subject’s last drink significantly predicted % HDD, so it was covaried in all analyses. The use of lorazepam for detoxification was also explored as a covariate, but it did not reduce the statistical significance of any significant effect. All significant interactions were followed up with simple effects testing, corrected for multiple comparisons.

For the drinking data, an intent-to-treat analysis of all subjects with at least one week of drinking data was used. The dependent variable was the proportion of days on which subjects drank heavily (%HDD;⩾five/four drinks in one day for men/women), binned into four 4-week periods. Because the A118G by medication interaction was greatest in the last month of treatment in COMBINE (Anton et al, 2008), a post hoc simple effect test within the larger mixed model was used to evaluate the main effect of medication separately in each genotype group for this period. A sensitivity analysis of subjects who completed the study (eg, were prescribed all study medications) and who had at least seven adherent urine riboflavin samples (out of nine total samples) was also conducted. In addition, change in % HDD between treatment and the post-treatment follow-up was analyzed using multi-level piecewise regression in HLM 7 (SSI, Skokie, IL).

For the imaging data, models were run separately for right and left VS. The dependent variable was VS ALC vs BEV percent signal change. For the analysis of the interaction between medication and between-scan abstinence, to reduce the possibility that subjects were non-abstinent simply because more time between scans had eclipsed, subjects scanned after week 2 (n=4, all non-abstinent) were excluded. Finally, to evaluate whether change in VS activation between scans interacted with medication in predicting treatment outcome, a between-subject factors for reduction in VS activation (median split; median reduction=0.023 (35% reduction from baseline)) was added to a model that also included a within-subject factor for time in study, a between-subject factor for medication, and all interactions. In this model, the dependent variable, %HDD, was binned into the two weeks following the second scan and each of the three subsequent 4-week periods of the study.

Results

Adherence

Adherence was examined separately for the samples collected at the week 1 and 2 visits, to assess adherence between scans, and for all nine samples collected during the study, to assess adherence across the entire medication period. Week 1 samples were available for 108 subjects with usable imaging data, of whom 96 were adherent, with no significant difference between medication groups (47/54 placebo and 49/54 NTX; χ2 (1, N=108)=0.38, p=0.54). Of these adherent subjects, 79 remained adherent at week 2, again with no significant difference between groups (36/46 placebo (1 subject’s value was missing) and 43/49 NTX; χ2 (1, N=95)=1.53, p=0.22). Adherence differences between the four medication/genotype groups were also not significant for the week 1 or 2 samples. For the remainder of the study, both riboflavin values and pill counts also indicated no significant adherence differences; the number of subjects taking ⩾80% of pills ranged from 79 to 89% across medication/genotype groups.

Drinking Outcomes

Effects of medication and OPRM1 genotype

There was a significant main effect of medication, such that individuals treated with NTX, relative to placebo, had less %HDD (F(1, 136.90)=5.30, p=0.023) over the 16-week treatment period (Figure 2). The interaction between genotype and time approached significance, such that %HDD increased over time among G-allele carriers, but it remained stable among A-allele homozygotes (F(3, 127.73)=2.64, p=0.053); the simple effect of genotype approached significance in the last month of treatment, such that G-allele carriers had more %HDD than A-allele homozygotes (F(1, 129.12)=3.67, p=0.058). There were no significant interactions between genotype and medication or between genotype, medication, and time. Nonetheless, planned simple effect analysis indicated that, in the last month of treatment, the simple effect of medication was significant among G-allele carriers (F(1, 124)=4.24, p=0.042), but not among A-allele homozygotes (F(1, 124)=0.32, p=0.57), such that G-allele carriers treated with NTX, relative to placebo, had less %HDD. In the exploratory analysis of completers with the greatest adherence (n=60; insets, Figure 2), although the genotype by medication interaction was not significant, the effect size (Cohen’s d) for NTX, relative to placebo, was 1.1 for G-allele carriers, but it was only 0.19 for A-allele homozygotes.

Percent heavy-drinking days (%HDD) by OPRM1 A118G genotype and medication group. The larger figures include all subjects included in the intent-to-treat analysis, and the insets include subjects who completed the study and had at least seven out of nine adherent riboflavin samples. Naltrexone (NTX), relative to placebo, significantly reduced %HDD across all 16 weeks. A118G genotype interacted with time, such that G-allele carriers’ %HDD increased over time, whereas A-allele homozygotes’ remained stable, but did not significantly moderate the effects of NTX on drinking. Figures are estimated marginal means±SE’s. Ns indicate the number of subjects who provided drinking data at each time point.

Post-treatment follow-up

Changes in %HDD during the treatment and post-treatment periods as a function of genotype and medication were evaluated (Figure 3). There was a significant interaction between genotype, medication, and time (B=0.063, SE=0.023, t(142)=2.78, p=0.006), such that G-allele carriers who received NTX increased their rate of heavy drinking once medication was stopped (B=0.048, SE=0.015, t(142)=3.23, p=0.002), whereas other groups’ %HDD remained stable.

Percent heavy-drinking days by smoking status at study entry and medication group. There was a significant interaction between smoking, medication, and time, such that %HDD increased over time among smokers, but not among non-smokers, and naltrexone, relative to placebo, ablated this increase among smokers. Figures are estimated marginal means±SE’s. Ns indicate the number of subjects who provided drinking data at each time point.

Moderation by smoking status

There was a significant main effect of smoking status (F(1, 139.34)=7.13, p=0.008), such that smokers had greater %HDD than non-smokers, as well as a significant interaction between smoking, medication, and time, such that %HDD increased over time among smokers, but not among non-smokers, and NTX, relative to placebo, ablated this increase among smokers (F(3, 128.21)=2.79, p=0.043; Figure 4). The simple effect of medication was significant during each month of treatment for smokers, but not for non-smokers. The interaction between smoking and medication was significant when smoking was evaluated as a continuous variable (F(1, 126.26)=4.27, p=0.041), such that individuals who smoked a greater number of cigarettes per day at baseline had less %HDD over 16 weeks on NTX, relative to placebo. There was no significant effect of medication on smoking rates or cigarettes smoked per day. Smoking did not significantly moderate the genotype by medication interaction.

Percent heavy-drinking days during the 16-week treatment period and the 24-week post treatment follow-up by OPRM1 A118G genotype and medication group. Regression lines were fit separately for each period. The genotype by medication by time interaction was significant, such that G-allele carriers who received naltrexone had an increased rate of heavy drinking once medication was stopped, whereas the other groups did not. Figures are estimated marginal means±SE’s. *p<0.05 for the simple effect of medication among smokers during each month.

Adverse effects

Four SAFTEE effects were significantly more frequent in the NTX group than the placebo group: nausea (p=0.026), diarrhea (p=0.004), abdominal pain (p=0.028), and dizziness (p=0.017). The genotype by medication interaction was not significant for these effects or any others. A time-varying covariate analysis, using GI complaints or dizziness as the covariate, indicated that the presence of these complaints did not significantly influence the effect of medication or its interactions with genotype or smoking on %HDD.

Imaging Outcomes

Between-scan stability

To test the stability of VS activation between scans, which we previously reported was high among non-treatment-seeking subjects (Schacht et al, 2011) and on which the study design was based, we first calculated, among placebo-treated subjects, the two-way mixed single-measure intraclass correlation coefficient, ICC(3,1), for each subject’s baseline and scan 2 values. Consistent with our previous findings, average within-subject stability between scans was good for both right (ICC(3,1)=0.43, p<0.001) and left (ICC(3,1)=0.36, p=0.003) VS.

Effect of OPRM1 genotype at baseline

We next evaluated whether genotype affected baseline VS activation. A-allele homozygotes had significantly greater right VS activation than G-allele carriers (F(1, 114)=6.33, p=0.01) and non-significantly greater left VS activation (F(1, 114)=1.95, p=0.17).

Effects of medication and OPRM1 genotype

For right VS, the interaction between medication and time was significant (F(1, 112)=4.03, p=0.047), such that NTX, relative to placebo, reduced activation more between scans (Figure 5). The simple effect of time was significant in the NTX group (F(1, 112)=4.49, p=0.036), but not in the placebo group. Although this difference was driven by greater reduction among NTX-treated A-allele homozygotes, the interaction between genotype, medication, and time was not significant (F(1, 112)=1.46, p=0.23). For left VS, the interaction between medication and time was in the same direction, but was not significant (F(1, 112)=2.31, p=0.13); the interaction between genotype, medication, and time approached significance (F(1, 112)=3.52, p=0.063), such that NTX, relative to placebo, reduced activation more among A-allele homozygotes.

Insets: regions of interest for right and left ventral striatum (VS). Main figure: alcohol cue-elicited activation in right (a) and left (b) VS at baseline and week 2 in each medication group. Naltrexone (NTX), relative to placebo, significantly reduced right VS activation between baseline and week 2. There was a significant main effect of A118G genotype on right VS activation at baseline, but genotype did not significantly moderate the effects of NTX on right (c) or left (d) VS activation. Figures are estimated marginal means±SE’s. *p<0.05 for an interaction between medication and time, and a simple effect of time within the NTX group.

Moderation by smoking status

Smoking did not significantly moderate the interactions between time and medication or between time, medication, and genotype on VS activation.

Moderation by early abstinence

On average, non-abstinent subjects drank 2.6 standard drinks per day (SD=2.3) between scans, with 3.3 heavy drinking days (SD=3.6). Abstainers had significantly more lead-in abstinence, more pre-randomization drinks per drinking day, and lower OCDS scores than non-abstainers, and trended toward being less likely to have recently used cocaine, but did not significantly differ in genotype, demographic variables, or ADS scores (Table 2). For right VS, the interaction between abstinence, medication, and time was significant (F(1, 108)=4.32, p=0.040), such that NTX, relative to placebo, reduced activation more among abstainers than non-abstainers. This interaction remained significant when any or all of the variables that significantly differed between abstainers and non-abstainers were covaried. The simple effect of time was significant in the abstinent/NTX group (F(1, 108)=8.06, p=0.005), but not in any other group (Figure 6). For left VS, the interaction between abstinence and medication was significant (F(1, 108)=4.92, p=0.029), such that abstainers who received NTX, relative to placebo, had less activation at both scans, whereas the opposite was true for non-abstainers. The interaction between abstinence, medication, and time was in the same direction as for right VS, but was not significant (F(1, 108)=1.32, p=0.25). Genotype did not significantly moderate any of these interactions for either right or left VS.

Alcohol cue-elicited activation in right (a) and left (b) VS in each medication group as a function of between-scan abstinence. NTX, relative to placebo, significantly reduced right VS activation only among subjects who abstained between baseline and week 2. Figures are estimated marginal means±SE’s. *p<0.05 for an interaction between abstinence, medication, and time; **p<0.01 for a simple effect of time within the abstinent/NTX group.

Prediction of drinking outcomes from medication and reduction in VS activation

For right VS, the interaction between medication and reduction in VS activation (between baseline and week 2) on subsequent drinking was significant (F(1, 109.71)=4.99, p=0.028), such that, among subjects with greater reduction in activation, those who received NTX, relative to placebo, had fewer subsequent heavy-drinking days. The simple effect of medication was significant in the group with greater reduction, but not in the group with less reduction, across all blocks (F(1, 109.75)=8.06, p=0.005) (Figure 7). As between-scan abstinence moderated the effects of NTX on right VS activation, percent days abstinent between scans was added as a covariate; it accounted for a large amount of variance in subsequent drinking (F(1, 108.26)=80.93, p=8.73 × 10−15), but the interaction between medication and reduction in right VS activation remained significant (F(1, 105.75)=5.02, p=0.027). For left VS, the interaction between medication and reduction in VS activation on subsequent drinking was not significant. When genotype was added to the models, the interaction between genotype and time was significant or approached significance, consistent with the results of the drinking outcomes model discussed above, but genotype did not significantly moderate the interactions between medication and reduction in VS activation on subsequent drinking.

Percent heavy-drinking days by the medication group and reduction in right VS alcohol cue-elicited activation between baseline and week 2. Subjects with greater reduction in activation who received NTX, relative to placebo, demonstrated significantly less heavy drinking throughout the medication period. Figures are estimated marginal means±standard errors. **p<0.01 for a simple effect of medication within the greater reduction group across all four months.

Discussion

Taken together, these data indicate several potential predictors of NTX response among treatment-seeking individuals with AUDs. Replicating previous findings, NTX reduced heavy drinking and alcohol cue-elicited VS activation. Further, as hypothesized, early abstinence moderated the effects of NTX on VS activation, and smoking and the magnitude of reduction in VS activation predicted reduced heavy drinking in the NTX group. However, OPRM1 A118G genotype did not moderate the effects of NTX on either the drinking or imaging outcomes.

With respect to the drinking outcomes, although there was a significant medication effect in the intent-to-treat analysis, the interaction with genotype was not significant over the full course of the study. In a sensitivity analysis among the most adherent subjects, the genotype by medication interaction was also not significant. Although small cell sizes for this analysis limit interpretation, there was nevertheless a large effect size for NTX only among G-allele carriers. Further, independent of medication, G-allele carriers’ drinking significantly increased over the course of the study relative to A-allele homozygotes. This difference was greatest at the end of the study, a time at which NTX showed some modification of drinking among G-allele carriers. Once medication was stopped, G-allele carriers who had received NTX had an increased trajectory to heavier drinking, unlike the other groups. These data are significant because, in COMBINE, the A118G interaction with NTX emerged over time and was strongest at the end of the trial (Anton et al, 2008), and subsequent re-analysis of COMBINE suggested that NTX was more effective than placebo only towards the end of the trial (Falk et al, 2010). Taken together, these data suggest that the A118G G-allele might confer liability to relapse to heavy drinking, which might not emerge immediately, but might be more evident over longer treatment periods. Thus, G-allele carriers could represent a specific subtype of AUD individuals who might benefit from longer NTX treatment and closer observation once medication is discontinued.

This study also replicated a previous re-analysis of COMBINE data (Fucito et al, 2012) that indicated greater NTX efficacy among AUD smokers, independent of the amount they smoked during the trial. Reasons for this finding need further exploration. The combined effects of nicotine and alcohol might increase VS dopamine (Tizabi et al, 2002), leading to sensitized effects of drinking in smokers (Piasecki et al, 2011). As such, the known effect of NTX in reducing VS dopamine (Benjamin et al, 1993; Gonzales and Weiss, 1998; Middaugh et al, 2003) might be the most salient among these individuals, leading to even less reinforcement, craving, and drinking than seen in non-smokers. Alternatively, smoking might be a proxy variable for other neurobiological adaptations that make smokers more responsive to NTX, such as changes in μ-opioid receptor binding (Weerts et al, 2014). Consistent with the findings of an older Cochrane report that found equivocal NTX efficacy for smoking cessation (David et al, 2006), the current study found no effect of NTX on smoking. Unfortunately, the trial was not designed and subsequently not statistically powered to detect an interaction between smoking status and A118G genotype on drinking.

With respect to the imaging outcomes, the most important finding from this study was that reduction in cue-elicited right VS activation predicted subsequent heavy drinking among NTX-treated subjects. The PREDICT study reported a similar finding; subjects with greater baseline VS activation, relative to those with less activation, responded better to NTX (Mann et al, 2014). Although PREDICT was placebo-controlled and included a second scan after 2 weeks of treatment (Mann et al, 2009), extant publications have not reported the effects of medication on cue-elicited activation; thus, the current study extends the PREDICT findings. Taken together, these results have important implications for both AUD neuroimaging and medications development. The clinical utility of the effects of medication on neuroimaging phenotypes has been debated, but the current data suggest a clinically meaningful result: individuals treated with NTX whose cue-elicited VS activation is reduced by a third or more may respond best to this medication. Further research should examine whether this effect is unique to NTX or shared with other efficacious AUD medications; as VS activation was also reduced among some placebo-treated subjects, it is possible that reduced VS activation may reflect a process associated with subsequent improvements in drinking but not specific to NTX. In any case, these data suggest that modern biomarkers (functional neuroimaging in this case) should continue to be evaluated and advanced to predict addiction treatment outcomes.

The main effect of NTX on right VS activation replicates and extends our previous findings in this region among non-treatment seekers (Myrick et al, 2008). Importantly, the current study addressed limitations of extant studies by employing a baseline scan and enrolling a large number of treatment-seeking subjects. A similarly designed but much smaller study reported that XR-NTX reduced cue-elicited activation in a variety of cortical areas, but not in VS or other subcortical areas (Lukas et al, 2013). Subjects in the study lacked VS activation at baseline, perhaps because they had much more lead-in abstinence (M=51 days) than our subjects and were administered olfactory alcohol cues, which less consistently elicit VS activation (Kareken et al, 2010; Schneider et al, 2001). In contrast, baseline VS activation in the current study was robust. Thus, our data suggest that oral NTX effectively reduces initially elevated cue-elicited VS activation in treatment-seeking individuals with AUDs.

NTX reduced right VS activation more among subjects who were abstinent between scans. Interestingly, abstinent placebo-treated subjects displayed no reduction in activation, and NTX had no effect on VS activation in non-abstinent subjects. NTX reduces VS dopamine transmission (Gonzales and Weiss, 1998), which is believed to underlie cue-elicited brain activation (Heinz et al, 2005). In contrast, short-term alcohol abstinence does not affect VS dopamine transmission (Rominger et al, 2012) and decreases cue-elicited activation of some brain areas, but not of VS areas (Brumback et al, 2015). The pairing of pharmacological effect of NTX with the effects of abstinence on cue-elicited activation of other areas may thus be necessary to achieve the greatest reduction in VS activation and needs further exploration. This finding could account for the utility of a lead-in abstinence period in many NTX trials, including a re-analysis of the XR-NTX trial, where the effects of XR-NTX were greater among individuals who were abstinent for at least 4 days before beginning medication (O'Malley et al, 2007).

Neither smoking nor A118G significantly moderated the effects of NTX on VS activation. The smoking by medication interaction on drinking was significant, but since the cue reactivity task was specific to alcohol cues, the absence of this interaction for VS activation is interesting but perhaps not surprising; future work that targets the effects of NTX among AUD smokers might consider the use of both smoking and alcohol cues (eg, Courtney et al, 2014). Several factors could explain the null pharmacogenetic effect. First, this result is consistent with the absence of a pharmacogenetic interaction on drinking during the medication period, as well as with four previous studies (Mann et al, 2014; Schacht et al, 2013c; Weerts et al, 2013; Ziauddeen et al, 2016), including PREDICT, where A118G genotype did not moderate relationships between baseline activation and the effects of NTX on drinking. Second, although previous studies have reported greater cue-elicited activation among G-allele carriers, these studies have primarily enrolled small numbers of non-treatment seekers with relatively low levels of drinking. This study included a large sample of treatment-seeking, heavy-drinking G-allele carriers, who displayed significantly less baseline VS activation than A-allele homozygotes, leaving less of an effect for NTX to reduce among these subjects. Finally, the G-allele has been associated with both increased β-endorphin-binding affinity for μ-opioid receptors (Bond et al, 1998; Weerts et al, 2013) and reduced OPRM1 mRNA and protein expression (Zhang et al, 2005); the latter effects might be associated with reduced cue-elicited activation among G-allele carriers.

All of the imaging outcomes reported here were specific to the right VS. A meta-analysis identified the right, but not left, VS as the area most consistently activated by alcohol cues (Schacht et al, 2013a). Our cue reactivity task consistently elicits right-sided VS activation (Myrick et al, 2004; 2008; 2010), and a combined fMRI/PET study also reported right-lateralized VS BOLD response and dopamine release to alcohol taste cues (Oberlin et al, 2016). We previously found better within-subject stability for right VS activation than left VS activation (Schacht et al, 2011) and replicated this finding in the placebo group here; thus, it was easier to detect a treatment effect on that side. The right-sided lateralization also recalls the work by Cahill et al (2004) on amygdala response to emotional memory, which found that men’s response was right-lateralized, whereas women’s response was left-lateralized; further exploration of sex differences in the effects of NTX on cue-elicited brain activation would be valuable.

Strengths of the current study include a large sample acquired at a single site, prospective and blinded genotyping, the use of a well-validated cue reactivity task, and a high proportion of subjects with complete 16-week drinking data. However, several factors limit its implications and generalizability. First, African-Americans were not included, secondary to low A118G G allele frequency. More research regarding pharmacogenetic or other predictors of NTX response for African-Americans is needed. Second, although subjects with current antidepressant and/or recent cocaine use were included to facilitate recruitment and extend generalizability to the treatment-seeking AUD population, these considerations may have altered the effects of medication on drinking or alcohol cue-elicited activation among these subjects. However, these factors were equally distributed across medication/genotype groups and did not affect baseline drinking or VS activation. Third, smoking severity assessment was limited to the ASI; more detailed evaluation of this variable, and the manner in which it may interact with NTX treatment, is needed. Fourth, the study was powered to detect a pharmacogenetic interaction on drinking, not cue-elicited activation, and recruitment fell slightly short of the targeted N. However, we previously reported a large effect of NTX, relative to placebo, on cue-elicited activation with groups of 20 (Myrick et al, 2008), suggesting that the moderating effect of A118G genotype would have to be quite small to avoid detection in the large sample enrolled here. Fifth, although models were run separately for right and left VS, the alpha level was not corrected for both comparisons. Our primary interest, given the findings noted above, was in right VS activation, but we examined left VS for completeness. Finally, other drug use was not assessed on the day of the second scan; however, very few subjects used other drugs (by self-report and urine drug screen at baseline).

In conclusion, this study evaluated several potential moderators of NTX response in AUD and found that smoking and changes in cue-elicited brain activation, rather than OPRM1 A118G genotype, were the best predictors of treatment outcome over 16 weeks. Continued research in this area may ultimately allow individual prediction of clinical response for AUD treatment.

Funding and disclosure

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism: R01 AA017633 (to RFA), K99/R00 AA021419 (to JPS), and K05 AA017435 (to RFA). RFA reports that, in the past 2 years, he has consulted for Novartis, Lundbeck, Indivior, and Xenoport, and has received grant funding from Eli Lilly. He is the Chair of the Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative (ACTIVE), which is conducted under the auspices of the American Society for Clinical Psychopharmacology and funded (currently or in the recent past) in part by Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Pfizer, Ethypharm, Invidior, Xenoport, and Otsuka. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Anton RF (1996). New methodologies for pharmacological treatment trials for alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 20 (7 Suppl): 3A–9A.

Anton RF, Moak DH, Latham PK (1996). The obsessive compulsive drinking scale: a new method of assessing outcome in alcoholism treatment studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 53: 225–231.

Anton RF, Oroszi G, O'Malley S, Couper D, Swift R, Pettinati H et al (2008). An evaluation of mu-opioid receptor (OPRM1) as a predictor of naltrexone response in the treatment of alcohol dependence: results from the Combined Pharmacotherapies and Behavioral Interventions for Alcohol Dependence (COMBINE)study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 65: 135–144.

Bach P, Vollsta Dt-Klein S, Kirsch M, Hoffmann S, Jorde A, Frank J et al (2015). Increased mesolimbic cue-reactivity in carriers of the mu-opioid-receptor gene OPRM1 A118G polymorphism predicts drinking outcome: a functional imaging study in alcohol dependent subjects. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 25: 1128–1135.

Benjamin D, Grant ER, Pohorecky LA (1993). Naltrexone reverses ethanol-induced dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens in awake, freely moving rats. Brain Res 621: 137–140.

Bond C, LaForge KS, Tian M, Melia D, Zhang S, Borg L et al (1998). Single-nucleotide polymorphism in the human mu opioid receptor gene alters beta-endorphin binding and activity: possible implications for opiate addiction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 9608–9613.

Brumback T, Squeglia LM, Jacobus J, Pulido C, Tapert SF, Brown SA (2015). Adolescent heavy drinkers’ amplified brain responses to alcohol cues decrease over one month of abstinence. Addict Behav 46: 45–52.

Bujarski S, O'Malley SS, Lunny K, Ray LA (2013). The effects of drinking goal on treatment outcome for alcoholism. J Consult Clin Psychol 81: 13–22.

Cahill L, Uncapher M, Kilpatrick L, Alkire MT, Turner J (2004). Sex-related hemispheric lateralization of amygdala function in emotionally influenced memory: an FMRI investigation. Learn Mem 11: 261–266.

Chamorro AJ, Marcos M, Miron-Canelo JA, Pastor I, Gonzalez-Sarmiento R, Laso FJ (2012). Association of micro-opioid receptor (OPRM1) gene polymorphism with response to naltrexone in alcohol dependence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addict Biol 17: 505–512.

Coller JK, Cahill S, Edmonds C, Farquharson AL, Longo M, Minniti R et al (2011). OPRM1 A118G genotype fails to predict the effectiveness of naltrexone treatment for alcohol dependence. Pharmacogenet Genomics 21: 902–905.

Courtney KE, Ghahremani DG, London ED, Ray LA (2014). The association between cue-reactivity in the precuneus and level of dependence on nicotine and alcohol. Drug Alcohol Depend 141: 21–26.

Courtney KE, Schacht JP, Hutchison K, Roche DJ, Ray LA (2016). Neural substrates of cue reactivity: association with treatment outcomes and relapse. Addict Biol 21: 3–22.

David S, Lancaster T, Stead LF, Evins AE (2006). Opioid antagonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD003086.

Falk D, Wang XQ, Liu L, Fertig J, Mattson M, Ryan M et al (2010). Percentage of subjects with no heavy drinking days: evaluation as an efficacy endpoint for alcohol clinical trials. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 34: 2022–2034.

Filbey FM, Ray L, Smolen A, Claus ED, Audette A, Hutchison KE (2008). Differential neural response to alcohol priming and alcohol taste cues is associated with DRD4 VNTR and OPRM1 genotypes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32: 1113–1123.

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW (2002) Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition. Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute: New York.

Fridberg DJ, Cao D, Grant JE, King AC (2014). Naltrexone improves quit rates, attenuates smoking urge, and reduces alcohol use in heavy drinking smokers attempting to quit smoking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38: 2622–2629.

Fucito LM, Park A, Gulliver SB, Mattson ME, Gueorguieva RV, O'Malley SS (2012). Cigarette smoking predicts differential benefit from naltrexone for alcohol dependence. Biol Psychiatry 72: 832–838.

Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O'Malley SS, Gastfriend DR, Pettinati HM, Silverman BL et al (2005). Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 293: 1617–1625.

Gelernter J, Gueorguieva R, Kranzler HR, Zhang H, Cramer J, Rosenheck R et al (2007). Opioid receptor gene (OPRM1, OPRK1, and OPRD1) variants and response to naltrexone treatment for alcohol dependence: results from the VA Cooperative Study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 31: 555–563.

Gonzales RA, Weiss F (1998). Suppression of ethanol-reinforced behavior by naltrexone is associated with attenuation of the ethanol-induced increase in dialysate dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci 18: 10663–10671.

Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, Stinson FS, Dawson DA (2004). Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 61: 1107–1115.

Heinala P, Alho H, Kiianmaa K, Lonnqvist J, Kuoppasalmi K, Sinclair JD (2001). Targeted use of naltrexone without prior detoxification in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a factorial double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 21: 287–292.

Heinz A, Siessmeier T, Wrase J, Buchholz HG, Grunder G, Kumakura Y et al (2005). Correlation of alcohol craving with striatal dopamine synthesis capacity and D2/3 receptor availability: a combined [18 F]DOPA and [18 F]DMFP PET study in detoxified alcoholic patients. Am J Psychiatry 162: 1515–1520.

Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Roache JD (2005). The COMBINE SAFTEE: a structured instrument for collecting adverse events adapted for clinical studies in the alcoholism field. J Stud Alcohol Suppl 157–167.

Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, Bobashev G, Thomas K, Wines R et al (2014). Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 311: 1889–1900.

Kareken DA, Bragulat V, Dzemidzic M, Cox C, Talavage T, Davidson D et al (2010). Family history of alcoholism mediates the frontal response to alcoholic drink odors and alcohol in at-risk drinkers. Neuroimage 50: 267–276.

King A, Cao D, Vanier C, Wilcox T (2009). Naltrexone decreases heavy drinking rates in smoking cessation treatment: an exploratory study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 33: 1044–1050.

Krystal JH, Cramer JA, Krol WF, Kirk GF, Rosenheck RA, Veterans Affairs Naltrexone Cooperative Study 425 Group (2001). Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. N Engl J Med 345: 1734–1739.

Lukas SE, Lowen SB, Lindsey KP, Conn N, Tartarini W, Rodolico J et al (2013). Extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX) attenuates brain responses to alcohol cues in alcohol-dependent volunteers: a bold FMRI study. Neuroimage 78: 176–185.

Mann K, Kiefer F, Smolka M, Gann H, Wellek S, Heinz A (2009). Searching for responders to acamprosate and naltrexone in alcoholism treatment: rationale and design of the PREDICT study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 33: 674–683.

Mann K, Vollstadt-Klein S, Reinhard I, Lemenager T, Fauth-Buhler M, Hermann D et al (2014). Predicting naltrexone response in alcohol-dependent patients: the contribution of functional magnetic resonance imaging. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38: 2754–2762.

McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O'Brien CP (1980). An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The Addiction Severity Index. J Nerv Ment Dis 168: 26–33.

Middaugh LD, Szumlinski KK, Van Patten Y, Marlowe AL, Kalivas PW (2003). Chronic ethanol consumption by C57BL/6 mice promotes tolerance to its interoceptive cues and increases extracellular dopamine, an effect blocked by naltrexone. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 27: 1892–1900.

Myrick H, Anton RF, Li X, Henderson S, Drobes D, Voronin K et al (2004). Differential brain activity in alcoholics and social drinkers to alcohol cues: relationship to craving. Neuropsychopharmacology 29: 393–402.

Myrick H, Anton RF, Li X, Henderson S, Randall PK, Voronin K (2008). Effect of naltrexone and ondansetron on alcohol cue-induced activation of the ventral striatum in alcohol-dependent people. Arch Gen Psychiatry 65: 466–475.

Myrick H, Li X, Randall PK, Henderson S, Voronin K, Anton RF (2010). The effect of aripiprazole on cue-induced brain activation and drinking parameters in alcoholics. J Clin Psychopharmacol 30: 365–372.

O'Malley SS, Garbutt JC, Gastfriend DR, Dong Q, Kranzler HR (2007). Efficacy of extended-release naltrexone in alcohol-dependent patients who are abstinent before treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol 27: 507–512.

O'Malley SS, Krishnan-Sarin S, McKee SA, Leeman RF, Cooney NL, Meandzija B et al (2009). Dose-dependent reduction of hazardous alcohol use in a placebo-controlled trial of naltrexone for smoking cessation. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 12: 589–597.

Oberlin BG, Dzemidzic M, Harezlak J, Kudela MA, Tran SM, Soeurt CM et al (2016). Corticostriatal and Dopaminergic Response to Beer Flavor with Both fMRI and [(11) C]raclopride Positron Emission Tomography. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 40: 1865–1873.

Oslin DW, Berrettini W, Kranzler HR, Pettinati H, Gelernter J, Volpicelli JR et al (2003). A functional polymorphism of the mu-opioid receptor gene is associated with naltrexone response in alcohol-dependent patients. Neuropsychopharmacology 28: 1546–1552.

Oslin DW, Leong SH, Lynch KG, Berrettini W, O'Brien CP, Gordon AJ et al (2015). Naltrexone vs placebo for the treatment of alcohol dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 72: 430–437.

Pettinati HM, Weiss RD, Dundon W, Miller WR, Donovan D, Ernst DB et al (2005). A structured approach to medical management: a psychosocial intervention to support pharmacotherapy in the treatment of alcohol dependence. J Stud Alcohol Suppl 170–178.

Piasecki TM, Jahng S, Wood PK, Robertson BM, Epler AJ, Cronk NJ et al (2011). The subjective effects of alcohol-tobacco co-use: an ecological momentary assessment investigation. J Abnorm Psychol 120: 557–571.

Ramchandani VA, Umhau J, Pavon FJ, Ruiz-Velasco V, Margas W, Sun H et al (2011). A genetic determinant of the striatal dopamine response to alcohol in men. Mol Psychiatry 16: 809–817.

Ray LA, Courtney KE, Hutchison KE, Mackillop J, Galvan A, Ghahremani DG (2014). Initial evidence that OPRM1 genotype moderates ventral and dorsal striatum functional connectivity during alcohol cues. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38: 78–89.

Reinhard I, Lemenager T, Fauth-Buhler M, Hermann D, Hoffmann S, Heinz A et al (2015). A comparison of region-of-interest measures for extracting whole brain data using survival analysis in alcoholism as an example. J Neurosci Methods 242: 58–64.

Rohn MC, Lee MR, Kleuter SB, Schwandt ML, Falk DE, Leggio L (2017). Differences between treatment-seeking and nontreatment-seeking alcohol-dependent research participants: an exploratory analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 41: 414–420.

Rominger A, Cumming P, Xiong G, Koller G, Boning G, Wulff M et al (2012). [18 F]Fallypride PET measurement of striatal and extrastriatal dopamine D 2/3 receptor availability in recently abstinent alcoholics. Addict Biol 17: 490–503.

Schacht JP, Anton RF, Myrick H (2013a). Functional neuroimaging studies of alcohol cue reactivity: a quantitative meta-analysis and systematic review. Addict Biol 18: 121–133.

Schacht JP, Anton RF, Randall PK, Li X, Henderson S, Myrick H (2011). Stability of fMRI striatal response to alcohol cues: a hierarchical linear modeling approach. Neuroimage 56: 61–68.

Schacht JP, Anton RF, Randall PK, Li X, Henderson S, Myrick H (2013b). Effects of a GABA-ergic medication combination and initial alcohol withdrawal severity on cue-elicited brain activation among treatment-seeking alcoholics. Psychopharmacology 227: 627–637.

Schacht JP, Anton RF, Voronin KE, Randall PK, Li X, Henderson S et al (2013c). Interacting effects of naltrexone and OPRM1 and DAT1 variation on the neural response to alcohol cues. Neuropsychopharmacology 38: 414–422.

Schneider F, Habel U, Wagner M, Franke P, Salloum JB, Shah NJ et al (2001). Subcortical correlates of craving in recently abstinent alcoholic patients. Am J Psychiatry 158: 1075–1083.

Sinclair JD (2001). Evidence about the use of naltrexone and for different ways of using it in the treatment of alcoholism. Alcohol Alcohol 36: 2–10.

Skinner HA, Allen BA (1982). Alcohol dependence syndrome: measurement and validation. J Abnorm Psychol 91: 199–209.

Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H et al (2004). Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. NeuroImage 23 (Suppl 1): S208–S219.

Sobell LC, Sobell MB (1992). Timeline follow-back: a technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Allen JP, Litten RZ (eds). Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biochemical Methods. Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, pp 41–72.

Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, Del Boca FK (1994). Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. J Stud Alcohol Suppl 12: 70–75.

Stritzke WG, Breiner MJ, Curtin JJ, Lang AR (2004). Assessment of substance cue reactivity: advances in reliability, specificity, and validity. Psychol Addict Behav 18: 148–159.

Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, Naranjo CA, Sellers EM (1989). Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict 84: 1353–1357.

Tizabi Y, Copeland RL Jr, Louis VA, Taylor RE (2002). Effects of combined systemic alcohol and central nicotine administration into ventral tegmental area on dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 26: 394–399.

Weerts EM, McCaul ME, Kuwabara H, Yang X, Xu X, Dannals RF et al (2013). Influence of OPRM1 Asn40Asp variant (A118G) on [11C]carfentanil binding potential: preliminary findings in human subjects. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 16: 47–53.

Weerts EM, Wand GS, Kuwabara H, Xu X, Frost JJ, Wong DF et al (2014). Association of smoking with mu-opioid receptor availability before and during naltrexone blockade in alcohol-dependent subjects. Addict Biol 19: 733–742.

Zhang Y, Wang D, Johnson AD, Papp AC, Sadee W (2005). Allelic expression imbalance of human mu opioid receptor (OPRM1) caused by variant A118G. J Biol Chem 280: 32618–32624.

Ziauddeen H, Nestor LJ, Subramaniam N, Dodds C, Nathan PJ, Miller SR et al (2016). Opioid antagonists and the A118G polymorphism in the mu-opioid receptor gene: effects of GSK1521498 and naltrexone in healthy drinkers stratified by OPRM1 Genotype. Neuropsychopharmacology 41: 2647–2657.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Xingbao Li and Scott Henderson for assistance with fMRI data collection; Scott Stewart for MM of some patients; Mark Ghent and Melissa Michel for assistance with subject recruitment and assessment; and Yeong-bin Im for performing the genetic and riboflavin assays. Portions of this work were presented at the 2016 International Society for Biomedical Research on Alcoholism meeting in Berlin.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schacht, J., Randall, P., Latham, P. et al. Predictors of Naltrexone Response in a Randomized Trial: Reward-Related Brain Activation, OPRM1 Genotype, and Smoking Status. Neuropsychopharmacol. 42, 2640–2653 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2017.74

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2017.74

This article is cited by

-

Neuromarkers in addiction: definitions, development strategies, and recent advances

Journal of Neural Transmission (2024)

-

Epigenetic moderators of naltrexone efficacy in reducing heavy drinking in Alcohol Use Disorder: a randomized trial

The Pharmacogenomics Journal (2022)

-

Effects of pharmacological and genetic regulation of COMT activity in alcohol use disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of tolcapone

Neuropsychopharmacology (2022)

-

The effects of nalmefene on the impulsive and reflective system in alcohol use disorder: A resting-state fMRI study

Psychopharmacology (2022)

-

A methodological checklist for fMRI drug cue reactivity studies: development and expert consensus

Nature Protocols (2022)