The inland province of Yunnan is home to many rare plants, and the critically endangered Yunnan Snub-nosed monkey. Credit: Xi Zhinong / Minden pictures/ Getty

Kunming's natural advantage

The region's natural and cultural bounty are making researchers worldwide take notice.

20 June 2017

Xi Zhinong / Minden pictures/ Getty

The inland province of Yunnan is home to many rare plants, and the critically endangered Yunnan Snub-nosed monkey.

On paper, China’s southwestern province of Yunnan is poor. It has one of the country’s lowest GDPs per-capita. The region is also prone to devastating earthquakes.

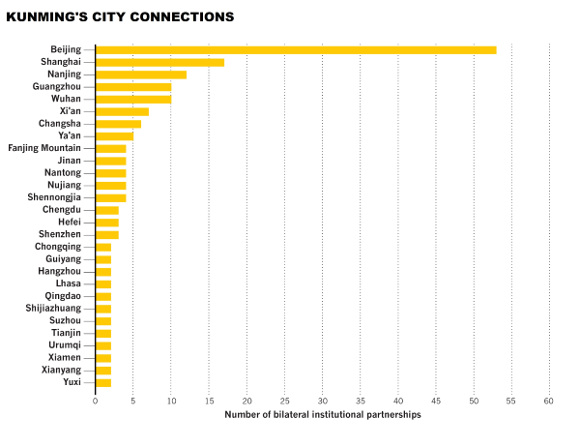

Yet its capital Kunming belies its size when considering its value as a research hub. Last year scientists at the city’s institutions formed 190 domestic research partnerships with other Chinese institutions to co-author papers included in the index. With a weighted fractional count (WFC) of 34.87, the research output of Kunming’s institutions remains small compared to giants like Beijing (WFC 1,663.04) and Shanghai (WFC 734.03). But, it ranks 16th of the 184 Chinese cities in the Nature Index for its number of domestic research partnerships.

Xu Jianchu, a pioneering Chinese ethno-ecologist, attributes this performance to scientists’ fascination with Yunnan’s cultural and biological diversity. The inland province contains more than half of China’s plant and animal species. Although Yunnan spans just 4% of China’s land mass, a comprehensive review published in Biodiversity & Conservation in 2004 found it contained 1,836 vertebrate species, including the critically-endangered golden monkey, and around 18,000 higher plant species, including more than 40% of China’s rare and endangered plants. Xu, who is based at the Kunming Institute of Botany, said this diversity gave Kunming-based scientists an advantage. “Any international and national partners who want to do research into plants, ecology, conservation — they need to collaborate with us,” Xu said.

More than two thirds of Kunming’s output in the Nature Index is in the field of chemistry, with many articles investigating the chemical structures and processes of plants.

Xu said Yunnan sits at the nexus of three “bio-diversity hotspots”: the mountains of southwest China, the eastern Himalayas, and Indo-Burma in the south (it shares borders with Burma, Laos and Vietnam). It has 25 officially-recognized minority ethnic groups and dozens of languages.

Xu is collaborating with researchers from the Xinjiang Institute of Geography and Ecology, part of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, to develop an ecological calendar for the region to monitor the impact of climate change on the mountain region using indicators from indigenous groups, as well as the group’s own studies.

He is also working on a joint study of fungi with Guizhou University that includes researchers from Beijing. Yunnan’s diverse fungi species are renowned across China where they are used in food and traditional Chinese medicine.

American social-ecological researcher R. Edward Grumbine first visited Yunnan in 2005 to understand the potential cultural and biodiversity impact of controversial efforts to dam the Nu river, which extends from the Tibetan plateau to the Andaman Sea. Captivated by the region’s diversity, Grumbine took on some small research projects while travelling between Yunnan and the US.

“Scholars who are interested in China, who do any kind of general homework at all, will come quickly to see the value of doing research in Yunnan,” he told Nature Index from Arizona, where he now works for a non-profit organisation. One was early 20th-century Austrian-American explorer and botanist Joseph Rock, whose stone-walled former residence still sits outside the historical town of Lijiang, near where Grumbine conducted fieldwork.

From 2010 to 2014, he worked with Xu’s team as a research fellow, part of a Chinese government effort to jump-start the publishing productivity of Chinese sciences in high-impact factor journals. About 150 international scholars were embedded in CAS research institutes across the country, he said. “Our job was to pursue what-ever research we wanted and to publish in the most prestigious journals that we could manage, and then act as lightning rods, role models [for] teams full of Chinese researchers.

”For Yunnan, efforts such as these are hampered by the brain drain that draws scientists to China’s more developed coastal cities. “We’ve lost several groups of researchers in recent years. They went to Shenyang. They went to Shanghai.” Xu contrasted Kunming with the coastal boomtown of Shenzhen in China’s southeast, where the private sector has attracted top talent. “Unfortunately, in Yunnan province we don’t have enough of a private sector,” he said. “We have government support, but compared to coastal areas the support is not so significant.”