Sara 'River' Dixon, a first year PhD student in the Biology Department at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, studies diligently between towers of boxes containing hundreds of zooplankton samples. She, and three other graduate students, use the boxes to create personal work spaces in the lab.

Credit: Kelly Robinson

Q&A Kelly Robinson: Sample archive serves as a plankton ecologist’s rainy-day fund

A massive collection of sea creatures turns out to be a gold mine of research opportunities.

22 November 2018

Kelly Robinson

Sara 'River' Dixon, a first year PhD student in the Biology Department at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, studies diligently between towers of boxes containing hundreds of zooplankton samples. She, and three other graduate students, use the boxes to create personal work spaces in the lab.

When Kelly Robinson started her faculty position at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, her postdoctoral advisor made her an offer she couldn't refuse.

Robinson studies the distribution of and interactions between plankton — dust-mote-sized, newly hatched sea creatures. To collect them, Robinson must charter a boat that can ferry her team into the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico and Straits of Florida — an expensive proposition. So, when her advisor offered her all the previously harvested ocean water she could carry, Robinson leapt at the opportunity.

Counting the dollar value of grants awarded to collect them, plus ship time, "It was something like US$4 million worth of NSF samples just sitting there for free. I was like, 'I'll take it'," she says.

For Robinson, the samples provide a hedge against the vagaries of grant funding. "It's a rainy-day data fund," she explains. "If I'm in a lean year where I don't have any projects funded, I have a bunch of data that I can just work with already."

But utilizing that collection turns out to be easier said than done. Those US$4 million worth of samples amounted to some 11,640 one-litre plastic containers full of plankton and preservative — enough to fill a small moving truck. It didn't need to be refrigerated, but it did need to be stored somewhere — mostly, her lab. In photographs, her two-room lab is filled with piles of cardboard boxes, up to 12 high, Robinson says. "The students actually use them to create little divisions for their spaces, like little forts."

We asked Robinson about her plans for this rainy-day fund.

Kelly Robinson

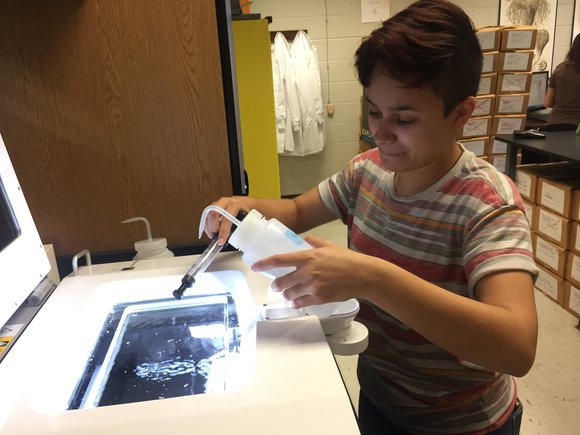

Victoria Gomez, a sophomore undergraduate student at UL Lafayette, prepares a zooplankton sample for processing with a bench-top plankton imaging system called a ZooScan.How do you keep track of 11,000+ jars of sample?

I hired a couple of undergrads. They went through every single box and they looked at every little sample and they created an inventory. At the same time, they checked to see if the samples had gone bad, or if they needed to be split to maintain the proper ratio of sample to preservative. Each sample's identity and location was logged in a spreadsheet, initially in Microsoft Excel and later in Google Sheets, as the students preferred entering data on their iPhones as they worked. It took them a year, but we now can basically cross-reference what I have in the lab against the database that was originally created for the project.

To find any one sample, we created a map indicating each box's general location. And so, while we can't put our hands on any one sample super-quickly, it helps us basically know what corner of the room we need to dig in to get it out.

What can you do with these samples?

These samples were collected to look at environmental drivers of variability in larval fish across the Straits of Florida. And so the original researchers collected larval fish, and in parallel, collected all other kinds of plankton with them. We also have all the environmental data that was collected with those samples, like temperature, salinity, density, when and where they were collected, and the ocean depth. So now we can ask some basic questions about different groups of plankton and how they interact. For instance, do we see changes in the community structure across different seasons? We would expect that we would. What about in space? What kind of assemblages develop in the higher productivity western part of the Straits versus the lower-productivity eastern part of the Straits? And then there's vertical distribution in the water column.

As your lab grows, space will become ever more of a premium. What will you do with these samples then?

Scientists are hoarders naturally, so the idea of getting rid of anything would break our hearts. And these samples are almost priceless: the folks who collected them are excellent scientists, and all the parts needed to generate really interesting papers are already there, they just need to be worked up. We’re 70% of the way there. It would be silly to throw that away for lack of space. So I will probably ask for more space, or I will pony up the money to pay for an appropriate external storage site for them. I would have to be very down on my luck to give these up.

Do you need to do any sort of routine maintenance or take any precautions to ensure the samples remain viable?

When I initially obtained them, we went through every single box. First, we needed to catalogue every sample that we had. And second, we had to look at the quality of the sample: sometimes they go bad, or the ethanol has to be changed. It took my students a year to catalogue everything. And we only did sample changes for about a third of what needed to be done. It's a labour-intensive effort, and it takes a lot of ethanol. So there are still a number of samples that we need to refresh the preservative. Otherwise, they'll just go bad and we’ll have to throw them out.

Have you had any disaster stories with your collection that you can share?

I was teaching one of my undergraduates how to count plankton in my office. And when we do this, we use a wash tub so that if you spill the sample, it doesn't go on the desk, and you can put it back in the jar. Well, somehow, this time the sample ended up all over the floor, and my student was devastated. And I was like, ‘it’s okay, it happens, let's just talk about what you did and we can learn how not to do that again’. So we recollected the sample as best we could and cleaned it up. And of course the floor was disgusting. And so now we just made that particular sample a practice sample, so it's okay if it gets messed up, because it's already messed up. But the students giggle about it, because they're like, ‘is this dog hair in this sample?’ And I'm like, ‘yeah, it ended up on the floor at one point’. So, you know, trying to make lemonade out of lemons.

What lessons can other researchers take from your experience?

Always try to generate little datasets when you have a little extra cash at hand, to have in your back pocket because they're going to come in handy for something: preliminary data for a grant, or even a manuscript. And make use of your professional network to pool resources. For example, I got about US$5,000, which is not a lot of money, to do monthly sampling off the coast of central Louisiana. I partner with a few different labs, and we're collecting all the data we can along this transect. I'm going to keep that going as long as I can to get preliminary data, because time-series always yield results.