As long-standing public science projects and innovation networks switch focus to the pandemic, volunteers are lining up to pitch in.

Credit: Kate Trifo/Unsplash

How hundreds of thousands of volunteers are using their skills to boost coronavirus research

Initiatives like Folding@Home and #WirVsVirus allow volunteers to pitch in, wherever they are.

7 April 2020

When David Wright saw the extent of the spread of COVID-19, he felt compelled to do what he could to help, despite having no previous experience in medical research. The business professor from the University of Ottawa in Canada soon found himself providing advice about setting up a clinical trial on a protective treatment against the disease.

What he does have is expertise in statistics, as a statistics lecturer and researcher in the economics of solar power. “If you get [the statistics] wrong, then you might spend a couple of years on that experiment” without a meaningful result, he says.

Wright was contacted by a researcher about the clinical trial after he registered his expertise through Crowdhelix, a UK-based research and innovation network that has set up a COVID-19 network. He has also signed up with a government-run program in Ontario, where he lives.

Citizens unite

Government- and community-led callouts for skills and talent are being answered by thousands, even hundreds of thousands, of people with something to offer, whether they are researchers, funding organizations or people stuck in isolation at home.

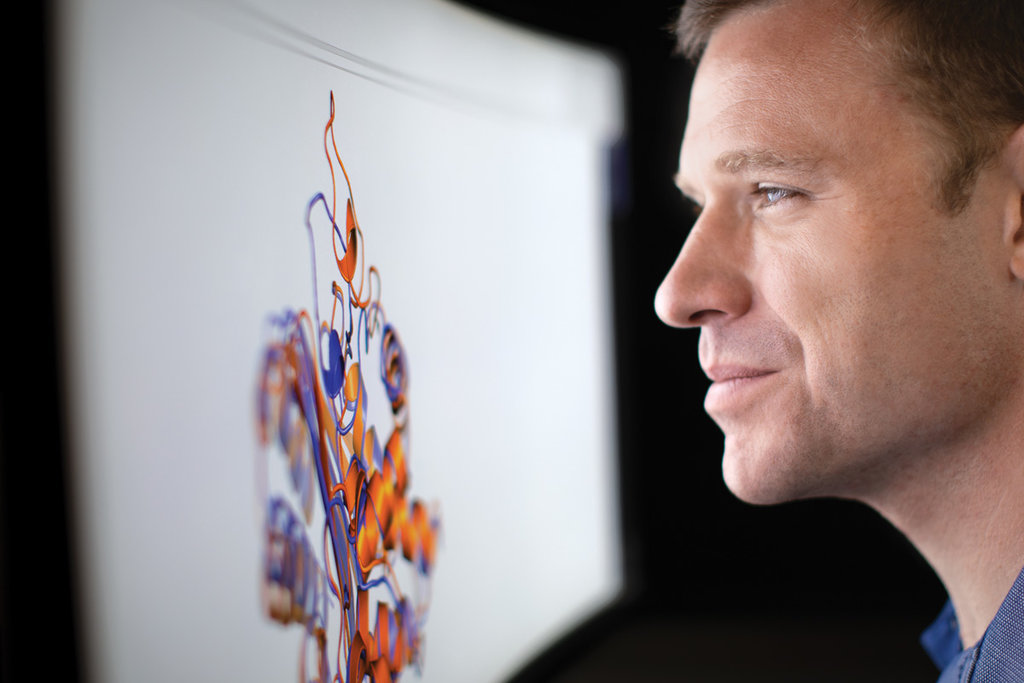

“The response has been enormous,” says Greg Bowman from Washington University in St Louis, in St Louis, Missouri, who heads up the citizen science project, Folding@Home.

Folding@Home harnesses unused computer processing power to identify potential drug targets for the virus that causes COVID-19. Since a call went out to the public at the end of February, the number of Folding@Home participants has ballooned from 30,000 to more than 700,000.

Folding@Home was modelled on the popular Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence – or SETI@Home – project, launched by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley in 1999. Folding@Home was launched by Stanford University the following year. It’s now a consortium in which more than a dozen institutions around the world participate.

Remotely mobilising spare computing power from volunteers’ home computers to run simulations of the myriad forms that a protein, jostling around in a cell, can fold into, Folding@Home looks for the ones that might make good drug targets. Earlier this year, the project identified a suitable binding site for drugs that could target what was thought to be an ‘undruggable’ Ebola protein essential for that virus’s replication.

The project is popular because people like to feel that they can make a difference, Bowman says. “One of the things that we can offer is giving your everyday citizen the chance to actually contribute to tackling this thing in a proactive way.”

Hack the virus

Researchers with more specialised skills are also looking for ways to contribute.

In early March, a German government-organized hackathon attracted more than 42,000 participants. The 48-hour event, called #WirVsVirus (‘Us vs the virus’), challenged computer programmers to form teams to find innovative solutions to problems posed by the pandemic.

Nearly 1500 ideas emerged from the hackathon, tackling challenges such as contact tracing, crisis communication, online learning and maintaining mental health in isolation. A Top 20 list of projects was selected by six juries of scientists, programmers and other professionals areas including medical care, diagnostics, and the economy. Selected projects deal with such challenges as optimising appointment scheduling to reduce exposure risk in a specialist’s waiting room and improving medical supplies using 3D printing.

Up to 150 projects will receive government funding. Several projects are already up and running, for example Feasibility, a phone service that connects elderly people without internet access with volunteers able to purchase goods on their behalf.

A similar event, the #BuildforCOVID19 hackathon, which is supported by tech behemoths including Amazon Web Services (AWS), Facebook, Giphy, Microsoft, Pinterest, Salesforce, Slack, TikTok, Twitter, and WeChat, took place a week later.

Almost 19,000 participants delivered more than 1,500 projects. Winners will be announced on April 10.

On the weekend of April 4-5, more than 4,000 participants took part in the #VersusVirus hackathon organised by CERN in Switzerland. Participants worked on 187 projects with the assistance of 500 mentors and funding from the Swiss government.

Matt Miller/Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis

Making connections

In the scientific community, researchers in France, Spain, and Germany banded together in March to form the Crowdfight COVID-19 initiative, which matches volunteer scientists with COVID-19 researchers in need of assistance.

The pandemic has prompted the UK-based research and innovation network, Crowdhelix, to expand its operations.

Crowdhelix had previously focussed its theme-based networks on membership and funding opportunities within the European Union, but its new COVID-19 network, headed up by the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, has gone global. It has also teamed up with the Brussels- and London-based think-tank, Science-Business, whose members will be alerted to funding opportunities around the world, and with infrastructure organisations who can research support and access to equipment from synchrotrons to computing facilities.

Members can announce projects where they are lacking specific expertise, such as in protein purification, for example, or writing an ethics application, and Crowdhelix will match them to suitable partners.

“It's a bit like a date,” says Crowdhelix director and co-founder, Michael Browne. “We're an intermediary; we're the connector.”

Around 200 scientists and other professionals have joined Crowdhelix since the call for a COVID-19 network went out, adding to the several thousand existing members of the other themed networks. “Everyone's rushing to this challenge,” says Browne.

“What we have now are global challenges, and they require, quite often, global actors and solutions coming together,” he says. The network is also aimed at overcoming what Browne describes as the “double whammy”: the desperate need for new collaborations to meet the COVID-19 challenge, just when social distancing and travel restrictions make such collaborations especially difficult.

Switch in focus

“The world needs this,” says Daniel Green, the CEO of Yaqrit, a London-based company that has posted a call-to-action on Crowdhelix. “It's too hard to find partners through an organically grown network.”

Yaqrit has been trialling devices that treat patients with end-stage liver disease. When research started emerging that the immune reaction in severe cases of COVID-19 bears similarities to end-stage liver disease, Green decided they had to act.

“What we had developed for liver patients could work in [COVID-19] patients,” he says.

For starters, Yaqrit is donating dozens of blood filtration devices left over from its clinical trial for treating liver disease to a trial for people with COVID-19. Now Yaqrit is seeking financial backing and collaborators who can run the trial.

Green is currently in discussions with potential clinical collaborators, and is still on the look-out for funding and collaborators to manage the logistics of a trial.

Meanwhile, Wright’s compulsion to contribute has left his own research at a distant third priority behind setting up online learning for all of his statistics courses, and helping out where he can on COVID-19 projects.

So far, he has assisted a researcher on Crowdhelix who wanted to run a clinical trial on a protective treatment for healthcare workers. Wright calculated the required number of participants and other necessary parameters for the trial to yield valid results.

“It turns out that the sample size needed to be quite high. And he decided that he simply didn’t have the resources to do that,” says Wright. “It wasn't a positive outcome in the sense of getting any useful progress,” against COVID-19, he says, but at least it prevented wasted effort.

“One of the exciting things is just seeing people come together over [COVID-19],” says Bowman. “I wouldn't stop washing your hands, but it is more gratifying to feel like you contributed to the science."