Credit: ANDRZEJ WOJCICKI/Getty Images

Call for human rights protections on emerging brain-computer interface technologies

Industry self-regulation is not enough, say AI researchers.

16 March 2021

ANDRZEJ WOJCICKI/Getty Images

Should a person who commits an assault during a psychotic episode be allowed to avoid jail if they agree to have a brain implant that controls their mental state? How much should it cost to have your intelligence augmented with a computer chip or to live in a world of virtual reality?

Such scenarios are not science fiction. According to the international NeuroRights Network (NRN), launched in 2020 by Columbia University neuroscientist Rafael Yuste, they describe the near-future.

In February, SpaceX founder Elon Musk announced that his firm Neuralink could begin human trials for brain implants this year. In 2019 Facebook bought self-described ‘neural interface technology’ start-up CTRL-Labs for an estimated US$500 million to $1 billion.

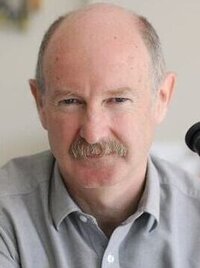

Rafael Yuste

The NRN argues that it’s time to consider governance systems for regulating the so-called brain-computer interface (BCI) technology underpinning such research. Its members include Marcello Ienca from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, Fabrice Jotterand from Basel University, also in Switzerland, Allan McCay from the University of Sydney in Australia, and Phillip Kellmeyer with Freiburg University in Germany.

As McCay, a lawyer, observes, it’s time to act in readiness for scenarios such as the assault case described above. “Criminal law as it stands is not well-equipped to deal with these kinds of issues,” he says.

Already, BCI can “read and decode activity of the brain with increasing accuracy”, says Yuste. He adds that progress is also being made on technology that is designed to control, or “write”, brain activity.

The current focus of BCI research is therapeutic: treating spinal cord injuries, depression and schizophrenia. It also seeks to enable people with disabilities to communicate with other persons and to control artificial limbs or objects in their environment via brain activity.

Global framework needed

The potential of BCI to enhance wellbeing is great, but there are serious human rights implications. The technology could enhance social inequity and offer hackers, governments or companies “new ways to exploit and manipulate people”, Yuste and his co-authors warned in a 2017 comment article in Nature.

Members of the NRN have contributed to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers international guidelines and standards for neurotechnology development. But they argue that self-regulation will not be enough.

“I simply don’t think that we should be naïve and presume that the ulterior aim of any of these big players in the emerging consumer market is to make the world a better and fairer place, especially for vulnerable people or groups in society,” says Kellmeyer, who heads the Neuroethics and AI Ethics Lab at his university’s Department of Neurosurgery.

The NRN calls for a multi-level approach to governance, starting with an international framework, or convention, pulling together the fundamental ethical and human rights arguments for the protection of mental privacy, mental integrity and personal identity. It argues that the principles must then be enforced with national legislation and regulation.

To date, no such governance exists. A push by the Chilean government to enshrine neurorights into the nation’s constitution to prevent misuse of neurotechnology comes closest. An accompanying neurorights bill to establish the legal parameters has also been passed by the Chilean Senate. Both are expected to pass the House in March. (See box-out below.)

Spain has started on a similar path. In November the government released the first draft of a Charter for Digital Rights that incorporates the neurorights proposed in the 2017 Nature comment article.

It’s designed to protect citizens’ rights and freedoms in a “changing digital environment due to the disruption of technological advance”. While not regulatory, it proposes a framework for public authorities seeking to boost the benefits of digital technology and minimise risks.

“I hope parts of the charter will be taken up legally,” says Yuste.

Chile sets sights on neurorights

Chile is poised to be the first nation to enshrine neurorights in its constitution.

The Chilean Senate has already passed a constitutional amendment and an accompanying bill, and both documents are expected to pass the Chamber in March. There is strong bipartisan and popular support, as well as backing from the academic and scientific world.

Inspired by the country’s history of human rights abuse and the neurorights advocacy of Rafael Yuste, the Chilean Senate's Future Committee launched both projects in 2019 to protect citizens from potential abuses by neurotechnology.

Senator Guido Girardi, head of the committee, was impressed with a presentation in Chile by Yuste three years ago and invited him to help the Senate consider the issue.

The resulting amendment and legislation address the emerging reality that mental processes will be increasingly monitored and influenced through brain–computer interfaces.

Specifically, the amendment defines cerebral integrity as inviolable and states that any intervention, even for health reasons, must be legally regulated and valid only with consent.

The bill supports the four neurorights proposed by Yuste and 24 other colleagues in a 2017 Nature comment article: mental identity and agency, mental privacy, fair access to mental augmentation and protection from bias and discrimination.

It also applies existing medical regulation to neurotechnological devices and mandates that all neurotechnology guarantees the physical and mental integrity of individuals.

To help map the next steps, the Future Committee is hosting a virtual neurorights workshop in March 17 to 19. Yuste and his NRN colleagues will participate.

After spending 33 years in the lab developing methods for mapping neuronal circuit activity, Yuste became passionate about developing an ethical code for the neurotechnology revolution he helped to kickstart.

He and colleagues proposed the large-scale mapping project leading to the Obama administration’s Brain Initiative, announced in 2013, and the International Brain Initiative, launched in 2017.

Yuste’s growing concern led to the establishment of the NeuroRights Initiative at Columbia University’s Neurotechnology Center. The NRN quickly followed.

Yuste explains that the NRN’s current goals involve continuing advocacy for neurorights regulation globally and gaining the support of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet.

He is hopeful that because Bachelet was President of Chile twice (in 2006-2010 and 2014-2018) before taking up the UN post in 2018, she is likely to be aware of the issues, providing a good foundation for dialogue.