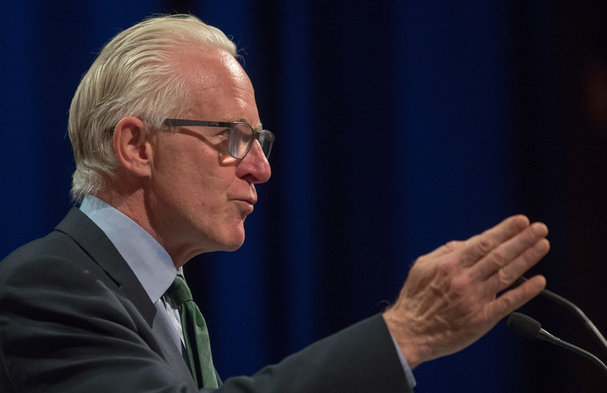

Further oversight on research integrity is crucial says inquiry head Norman Lamb.

Credit: Matt Cardy/Stringer/Getty

British universities fail at research integrity self-regulation

One-quarter of surveyed institutions admit to not complying with guidelines.

11 July 2018

Matt Cardy/Stringer/Getty

Further oversight on research integrity is crucial says inquiry head Norman Lamb.

The United Kingdom should establish a committee to monitor efforts by the nation’s universities to properly conduct misconduct investigations, a parliamentary inquiry recommends.

The guidance follows a new report released on 11 July, revealing that one in four UK universities does not comply with research integrity guidelines released six years ago. Their failure to adhere makes it difficult to determine the scale of the problem.

“Establishing a new national Research Integrity Committee is crucial,” says committee chairman and member of parliament, Norman Lamb. “It’s not a good look for the research community to be dragging its heels on this, particularly given research fraud can quite literally become a matter of life and death.”

Universities UK (UUK), an advocacy group representing most of the nation’s higher-education institutions, issued a concordat to support research integrity in 2012 after a parliamentary inquiry raised concerns over the country’s handling of the issue. The concordat requires that universities deal with misconduct cases transparently and robustly or face losing their funding from agencies.

The US Office of Research Integrity defines research misconduct as “fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism in proposing, performing, or reviewing research, or in reporting research results”.

For the inquiry, the UK parliament's Science and Technology Committee — on which sit 11 members of parliament — contacted 136 UK universities to ask whether they publish information about the number of research misconduct investigations they conduct annually. Around 25% said they didn’t, the report says, with some citing concern that such transparency could undermine their public image. The report says there is a need to address the potential conflicts faced by universities' self-policing in the current system.

It is “worrying and disappointing” that some universities are not doing any annual reporting on the matter, says James Wilsdon, a research policy scholar at the University of Sheffield, who has been an institutional lead for misconduct investigations. Wilsdon agrees that the creation of a committee will be useful. “But we need to ensure that the system of oversight remains light touch and trust-based, and geared towards the clear majority of institutions who are addressing these issues." That is preferable to "a bureaucratic and heavy-handed response to the far smaller number of laggards,” he says.

The lack of compliance by universities, despite it being a prerequisite for eligibility for grants from major funders, might be partially attributable to the lack of penalties imposed, the report notes.

A UUK spokesperson said: “Universities UK will meet the concordat signatories to go through the recommendations of the report and take forward any necessary action.”

Canada and Australia already have committees with a similar function to the one proposed, and China is introducing oversight of investigations by their Ministry of Science and Technology. The new committee should work closely with the newly established United Kingdom Research and Innovation (UKRI), a new unified funding agency, and publish an annual report on the state of research integrity in Britain, the report says.

“Such a body is needed for all countries or global regions,” says Matthew Hodgkinson, head of research integrity at the open access publisher Hindawi in London. “Investigations that explore how misconduct occurred and how it can be avoided are more constructive than those which narrowly focus on questions of guilt,” he adds, “as these can fail to correct real errors when exonerating or condemning individual researchers.”

The report recommends that universities, funders and publishers should share information about misconduct inquiries. An investigation by the BBC last year found that at least 300 allegations of research misconduct had been reported at 23 out of 24 Russell Group universities between 2011 and 2016. Around a third of allegations of plagiarism, fabrication, piracy and misconduct were upheld, the BBC reported, and more than 30 studies were retracted.

Hodgkinson notes that even in the absence of a formal misconduct finding, failing to act brushes problems under the carpet. “Universities and publishers fixing errors and investigating misconduct should be celebrated and not seen as a badge of shame,” he says.