Abstract

The perception that intracellular lipolysis is a straightforward process that releases fatty acids from fat stores in adipose tissue to generate energy has experienced major revisions over the last two decades. The discovery of new lipolytic enzymes and coregulators, the demonstration that lipophagy and lysosomal lipolysis contribute to the degradation of cellular lipid stores and the characterization of numerous factors and signalling pathways that regulate lipid hydrolysis on transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels have revolutionized our understanding of lipolysis. In this review, we focus on the mechanisms that facilitate intracellular fatty-acid mobilization, drawing on canonical and noncanonical enzymatic pathways. We summarize how intracellular lipolysis affects lipid-mediated signalling, metabolic regulation and energy homeostasis in multiple organs. Finally, we examine how these processes affect pathogenesis and how lipolysis may be targeted to potentially prevent or treat various diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Fatty acids (FAs) are essential biomolecules for all organisms. Their oxidation generates the highest energy yield for ATP or heat production of all common energy substrates. They are indispensable components of membrane lipids, and FA anchors enable peripheral membrane proteins to be tethered to biological membranes. Additionally, specific FAs act as highly bioactive signalling molecules or serve as their precursors. Besides these vital functions, FAs also exert toxic properties (‘lipotoxicity’) when their intra- and/or extracellular concentrations exceed physiological levels. Lipotoxicity results from the ability of FAs to act as detergents, to affect acid–base homeostasis and to generate highly bioactive lipids, such as ceramides and diradylglycerols (diglycerides, DGs). Together, these processes cause cellular stress and dysfunction, leading to various forms of cell death1.

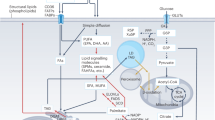

To efficiently and safely store large amounts of FAs in cells and tissues, they are covalently esterified to the trivalent alcohol glycerol to yield triradylglycerols, commonly called triglycerides (TGs) or ‘fat’. Essentially every cell type can store TGs to some degree in intracellular organelles termed lipid droplets (LDs)2. In mammals and many other vertebrates, the majority of TGs is deposited in adipocytes of adipose tissue. While TGs represent an efficient, inert form of FAs for storage and transport, they are unable to traverse cell membranes. Accordingly, TG transport into or out of cells either requires their hydrolytic breakdown into FAs and glycerol or their specialized-vesicle-mediated transport across cell membranes. The latter process comprises secretion and uptake of TG-rich lipoproteins or TG transport by extracellular vesicles (EVs). The hydrolysis of TGs is catalysed by lipases in a process called lipolysis. Extracellular lipolysis in the gastrointestinal tract and the vascular system degrades TGs to provide FAs and monoradylglycerols (monoglycerides, MGs) to the underlying parenchymal tissues. Conversely, intracellular lipolysis releases FAs from LD-associated TGs in the cytoplasm or lipoprotein-associated TGs in lysosomes. Extracellular lipases of the digestive tract and the vascular system mostly belong to the pancreatic lipase gene family. Intracellular lipases are structurally unrelated to this family and have been subclassified as (1) lipases with an optimum pH around 7 (‘neutral lipases’), which are responsible for the degradation of cytosolic LDs, and (2) lipases with an optimum pH around 5 (‘acid lipases’), which are localized to lysosomes. Accordingly, the two intracellular canonical pathways responsible for TG degradation are termed neutral and acid lipolysis (Fig. 1). In accordance with the fundamental function of lipases, their dysfunction or deficiency often causes severe pathologies including dyslipidaemias and lipid-storage diseases. More indirectly, lipase activities and lipolytic processes affect many aspects of homeostasis and have been associated with the pathogenesis of obesity, type 2 diabetes, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), cancer, heart disease, cachexia, infectious diseases and others.

Consecutive hydrolysis of TGs by ATGL, HSL and MGL or ABHD6, generating FAs and glycerol (G). Transesterification of DGs or MGs with DG, generating TGs, is catalysed by ATGL. In acid lipolysis, TGs are sequestered from LDs via lipophagy and are subsequently hydrolysed by LAL in lysosomes (Lys), generating FAs and glycerol.

Canonical enzymology of neutral lipolysis

Recognition that enzyme-catalysed TG hydrolysis must precede membrane passage was achieved early in the 20th century3, yet it took more than 50 years to identify and characterize the first intracellular TG hydrolase that participates in the process. In 1964, Steinberg and colleagues described hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) as the key hydrolase in the degradation of TGs and DGs and the role of monoglyceride lipase (MGL) in MG hydrolysis in adipocytes4. HSL was considered rate-limiting for TG hydrolysis for the following four decades, but observations that HSL-deficient mice maintained hormone-induced FA release in adipose tissue, lacked obesity and accumulated DGs5,6 finally argued for the involvement of alternative enzymes and mechanisms in TG hydrolysis. An extensive search for these alternatives led to the discovery of a new enzyme, called adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL)7 or Ca2+-independent phospholipase-A2-ζ (iPLA2-ζ)8, and its coactivator, named α/β hydrolase domain-5 (ABHD-5; also called comparative gene identification-58, CGI-58)9. The biochemical characteristics and enzymatic activities of ATGL, HSL and MGL are summarized in Table 1 and Fig. 1.

Adipose triglyceride lipase

Human adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) is a 504-amino-acid protein. It harbours a patatin domain named after a structural unit in patatin, which is a relatively weak phospholipase present in potato tubers7. The human genome carries nine genes encoding patatin-domain-containing proteins, which are designated patatin-like phospholipase domain 1–9 (PNPLA1–PNPLA9)10. PNPLA2 encodes ATGL. The patatin domain of ATGL is embedded in a typical α−β−α hydrolase fold located in the amino-terminal half of the enzyme. It contains a catalytic dyad consisting of S47 and D166. Interestingly, the carboxy-terminal half of the enzyme is dispensable for enzyme activity on lipid emulsions but essential for LD binding and TG hydrolysis in cells11. The molecular basis for the requirement of this C-terminal region for enzyme binding to LDs is poorly understood. It may involve a hydrophobic stretch (amino acids 315 to 364) and two potential phosphorylation sites (S406, S430). However, the protein kinases thought to be involved and the impact of ATGL phosphorylation on its LD localization and activity remain controversial12,13 and require further study.

Long-chain FA-containing TGs represent by far the best substrates for ATGL, while FA esters in DGs, glycerophospholipids or retinylesters are only poorly hydrolysed. Interestingly, however, the enzyme exhibits transacylase activity leading to the formation of TG and MG8,14,15 from two DG molecules in a disproportionation reaction. Whether this anabolic function of ATGL is physiologically relevant remains unanswered, as is the question of whether ATGL acts as a transacylase with alternative FA-donor or FA-acceptor substrates. ATGL shares transacylation activity with other members of the PNPLA family, including PNPLA1 and PNPLA3 (refs. 8,16). Overall, despite a high potential for physiological relevance, this coenzyme-A-independent esterification reaction and its role in lipid remodelling remain elusive.

Specific transport mechanisms guide ATGL from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane to LDs. The structural features within ATGL that determine its effective trafficking are still insufficiently understood. More is known about the role of factors involved in ATGL transport. Deletion of key transport vesicle components or effectors, including ADP ribosylation factor-1 (ARF-1), small GTP-binding protein-1 (SAR-1) or Golgi-Brefeldin A resistance factor (GBF-1), as well as deficiency of the coat protein complex-I (COP-I), prevent ATGL translocation and lead to defective TG hydrolysis and LD accumulation17,18. The list of factors that affect ATGL translocation was recently extended by oxysterol-binding protein like-2 (OSBP-2) and family with sequence similarity 134, member B (FAM134B). OSBP-2 forms a complex with the COP-I subunit COP-B1 and binds ATGL, directing the enzyme to LDs19. FAM134B is a Golgi-associated protein that regulates the vesicular transport of ATGL and other proteins to LDs via Arf-related protein-1 (ARFRP1)20.

Loss-of-function mutations in the PNPLA2 gene cause neutral lipid storage disease with myopathy (NLSDM) in humans21. Currently, approximately 100 people with the condition with more than 30 different mutations have been identified. Onset and severity of disease are highly variable, arguing for gene–gene and gene–environment interactions that contribute to the clinical presentation of the disease22. Most people with the disease develop steatosis in multiple tissues, with TG deposition in cardiac and skeletal muscle, pancreas, liver and leucocytes (Jordan’s anomaly). Progressive skeletal myopathy is common in people with NLSDM and leads to pronounced motor impairment. More than half of all affected individuals have severe dilated cardiomyopathy, and many require heart transplantation for survival23.

ATGL deficiency in mice phenocopies many of the clinical findings in people with NLSDM, but the murine condition is more serious, leading to cardiomyopathy and death without exception when the animals are 3 to 4 months old24. ATGL deficiency in the heart leads not only to a severe TG accumulation in cardiomyocytes, but also to a striking defect in the activation of the transcription factor peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPARα), reduced mitochondrial biogenesis and function, and defective respiration, which eventually causes lethality25. Restoring ATGL expression in the heart of ATGL-deficient mice rescues the cardiac phenotype, prevents premature lethality25 and may therefore provide a potential treatment strategy for people with NLSDM. These initial studies in ATGL-knockout (ATGL-KO) mice highlighted the crucial role of the enzyme for lipolysis not only in adipose tissue, but also in major energy-consuming organs, such as the heart. They also demonstrated that, in addition to its important role for the provision of energy substrates, ATGL-mediated lipolysis also participates in the regulation of major signalling pathways that regulate energy homeostasis. These pathways include insulin signalling26,27 and nuclear receptor signalling via PPARα (refs. 25,28), PPARγ (ref. 29) and PPARδ (refs. 30,31), as well as protein and histone acetylation and deacetylation processes that affect gene transcription32,33. The lipolysis-dependent regulation of PPAR activation involves transcriptional33 and post-transcriptional mechanisms34.

Hormone-sensitive lipase

Hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) is a structurally unique member within the large Ser-lipase/esterase family of enzymes in the animal kingdom. In fact, the closest structural relatives of HSL are found in prokaryotes, archaea and plants. The structure of the mammalian LIPE gene, which encodes HSL, as well as the enzyme’s function, properties and regulation, were recently extensively reviewed by Recazens et al.35. Tissue-specific protein isoforms, ranging from 775 amino acids (in most tissues) to 1,088 amino acids (in testis), result from alternative transcription start sites and exon usage. HSL exhibits broad substrate specificity with highest activity against DGs and cholesteryl esters (CEs), followed by TGs, MGs, retinyl esters and short-chain acyl esters. The enzyme harbours five serine phosphorylation sites, which are targeted by multiple protein kinases and have important regulatory functions affecting enzyme activity (see section on regulation of lipolysis).

Important insights into the physiological role of the enzyme in humans were revealed by clinical characterization of homozygous individuals with HSL deficiency and heterozygous carriers of loss-of-function LIPE gene mutations36,37. HSL deficiency manifests in a more benign phenotype than does ATGL deficiency. It is characterized by relatively mild forms of dyslipidaemia, hepatic steatosis, partial lipodystrophy and type 2 diabetes. HSL-deficient adipose tissue consists of small, insulin-resistant adipocytes, which exhibit increased inflammation and impaired glycerol release upon lipolytic stimulation36. Partial lipodystrophy results from a downregulation of PPAR-γ and its downstream target genes when HSL is lacking, leading to reduced adipogenesis and insulin sensitivity. Notably, HSL also regulates the transcriptional activity of another nuclear receptor, carbohydrate responsive element binding protein (CHREBP)38. Independent of its hydrolytic activity, HSL binds to CHREBP and thereby prevents its translocation into the nucleus, reduces target gene expression and leads to insulin resistance. Conversely, blocking HSL binding to CHREBP increases target gene expression and insulin sensitivity38. However, the fact that people with reduced or no HSL expression are generally more insulin resistant than are individuals with normal HSL expression36,37 suggests that the HSL-mediated regulation of insulin sensitivity via CHREBP is not a predominant regulatory mechanism of insulin sensitivity in humans.

Mice deficient in HSL phenocopy ATGL-deficient mice with PPARγ-dependent lipodystrophy in adipose tissue5,30,39,40, suggesting that the regulation of these nuclear receptors by lipolysis is not enzyme-specific. HSL has a prominent role in DG hydrolysis within the lipolytic cascade as mice lacking HSL accumulate DGs in various tissues6. Finally, in contrast to humans, HSL-deficient mice are sterile owing to defective spermatogenesis, sperm motility and fertility5,41. The molecular basis for this species-specific difference of enzyme function in spermatogenesis remains to be discovered.

Monoacylglycerol lipase and α/β hydrolase domain-6

Monoacylglycerol lipase (MGL) was the first characterized MG hydrolase (Table 1)42,43. The enzyme hydrolyses both sn-1 MG and sn-2 MG, in which FAs are esterified to the terminal or middle hydroxyl group of the glycerol backbone, respectively, to generate glycerol and FAs. Although the preferred substrate for MGL are MGs, the enzyme was also shown to hydrolyse prostaglandin-glycerol esters and FA-ethyl ethers44,45,46. MGL expression is subject to nutritional47 and PPARα-dependent regulation48, and MGL protein is targeted for proteasomal degradation involving Staphylococcal nuclease and tudor domain-containing 1 (SND1)49. To date, no post-translational modifications of the enzyme are known to affect enzyme activity.

In addition to MGL, several other enzymes are reported to hydrolyse MGs. Their physiological impact in vivo is unclear in most cases, with the exception of α/β hydrolase containing-6 (ABHD6). ABHD6 comprises 337 amino acids with an active site composed of S148, D278 and H306. It is localized to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane and preferentially hydrolyses FAs at the sn-1 position over the sn-2 position of MGs. ABHD6 also hydrolyses other substrates, including lysophospholipids50 and bis(monoacylglycerol)-phosphate51,52. The highest expression levels of ABHD6 are observed in liver, kidney, intestine, ovary, brown adipose tissue and pancreatic beta cells. In some tissues (for example pancreas) and cancer cell lines that have low MGL expression, ABHD6 becomes the main MG hydrolase53 and has been associated with the development of insulin resistance50 and cancer progression54,55.

Since the catabolic pathways of TGs and glycerophospholipids (PLs) converge in the formation of MGs, it is difficult to assign specific phenotypes resulting from enzyme overexpression or deficiency to changes in TG-derived versus PL-derived MGs. MGL deficiency in mice causes MG accumulation in various tissues, minor changes in plasma very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) metabolism, impaired intestinal lipid absorption and a moderate protection from diet-induced obesity and hepatic steatosis56,57,58. Most severe accumulation of MGs is observed in brain with high levels of 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG)59,60. 2-AG belongs to a class of signalling lipids called endocannabinoids, which act as retrograde neurotransmitters and affect diverse physiological processes. In mice, MGL deficiency ameliorates neuroinflammation and cancer malignancy owing to diminished 2-AG hydrolysis and reduced arachidonic acid availability61,62,63,64. Pharmacological inhibition or genetic deletion of ABHD6 also increases sn-1 and sn-2 MG concentrations in different tissues, thereby altering multiple aspects of metabolism and energy homeostasis53,65. ABHD6 inhibition induces insulin secretion, adipose tissue browning and brown adipose tissue activation, and exerts neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects. The different phenotypes arising from MGL or ABHD6 inhibition remain poorly understood and may be explained by their different cellular localization and expression patterns.

The complex regulation of canonical lipolysis

Energy-substrate demand during food deprivation represents the major driver of lipolysis (‘induced lipolysis’). The subsequent release of FAs from white adipose tissue induces a metabolic switch in many energy-consuming tissues from glucose to FA utilization. Simultaneously, the upregulation of hepatic gluconeogenesis and glucose secretion provides glucose to glucose-dependent cells and tissues. Conversely, low lipolytic rates in the fed state (‘basal lipolysis’) lead to decreased FA and increased glucose utilization in tissues with high energy demand and fat deposition in adipose tissue. The ability of cells and organs to switch between different energy substrates such as FAs and glucose defines their ‘metabolic flexibility’. Numerous endocrine, paracrine and autocrine factors, including hormones, cytokines and neurotransmitters, trigger the switch between basal and induced lipolysis by regulating the major lipolytic enzymes ATGL and HSL on multiple levels, including gene transcription, post-translational protein modifications and, in the case of ATGL, regulation by enzyme coactivators and inhibitors. The classical activation pathway in adipocytes involves catecholamines, which activate both enzymes ATGL and HSL via hormonal (epinephrine) or sympathetic-neuronal (norepinephrine) stimulation. Other activating hormones and cytokines include glucocorticoids, thyroid hormone, eicosanoids, atrial natriuretic peptides, growth hormone, interleukins, tumour necrosis factor α, leptin and many others66. Insulin represents the classical inhibitory hormone for ATGL and HSL.

Transcriptional control of ATGL and HSL expression

Regulation of lipase gene transcription is a major mechanism controlling lipolysis (summarized in Fig. 2). Unfortunately, the transcriptional control elements in the promoters of the genes coding for ATGL (Pnpla2) and HSL (Lipe) have not been sufficiently characterized. Evidence suggests that both genes are direct targets for the PPAR family of nuclear receptor transcription factors67,68,69. Other members of the nuclear receptor family, RXR, LXR-α and steroidogenic factor-1, are specific for Lipe and do not regulate Pnpla2 transcription70,71. The Lipe promoter also contains a sterol regulatory element rendering Lipe gene expression subject to sterol regulatory element binding proteins (SREBPs)72. Several transacting factors that drive adipogenesis, for example, the G/C-box-binding factor specificity protein-1 (SP1), E-box-binding transcription factor-E3 (TFE3) or CEBPα, also regulate transcription of Pnpla2 and Lipe67,68,73,74.

Several transcription factors, including the PPAR family of nuclear receptor transcription factors, SP1, TFE3 and CEBPα, regulate the transcription of Pnpla2 and Lipe. Other members of the nuclear receptor family, RXR, LXR-α and SF1, as well as SREBPs are specific for Lipe, but do not regulate Pnpla2 transcription. Pnpla2 expression is activated by FOXO1, STAT5, EGR1, and inhibited by SNAIL1. STAT5 is phosphorylated and activated by JAK2, and is dependent on GHR activation. GHR also activates the MAP kinase pathway involving ERK-1/2 to downregulate G0S2 and FSP27 transcription, which increases ATGL activity. MAP also activates ERK-3 to increase FOXO1-mediated ATGL transcription. On the contrary, IR activation inhibits Pnpla2 transcription by the PKB- and CDK1-catalysed phosphorylation of FOXO1, which leads to 14-3-3 protein interaction and cytoplasmic retention of the transcription factor. Moreover, DNA binding of FOXO1 is abrogated by lysine acetylation via cAMP-responsive element binding protein (CBP)/p300. Members of the SIRT family of NAD+-dependent deacetylases reverse this inhibitory effect and restore expression of Pnpla2. Neutral lipolysis is further regulated by mTORC1 and mTORC2, enabling cells to react to nutrient availability. mTORC1 regulates Pnpla2 transcription by inhibiting EGR1, while mTORC2 inhibits lipolysis by activating PKB-mediated FOXO1 phosphorylation. Rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR (Rictor) inhibits SIRT-mediated deacetylation of FOXO1 and Pnpla2 expression through a yet unknown mechanism.

While catecholamines exert their prolipolytic effects predominantly on the level of enzyme activities, other lipolysis-activating hormones and cytokines act primarily via transcriptional control of lipase expression. For example, growth hormone (GH) induces Pnpla2 transcription via two distinct mechanisms. The predominant pathway involves GH binding to its receptor and subsequent activation of the transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription-5 (STAT5) through Janus kinase-2 (JAK2)-catalysed phosphorylation. Phospho-Stat-5 directly activates Pnpla2 transcription in white and brown adipocytes75,76. Consistent with this finding, JAK2 or STAT5 deletion impairs lipase expression75,77. Independent of STAT5, GH additionally triggers the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathway activating extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1/2 (ERK-1/2). ERK1/2 phosphorylates the β3-adrenergic receptor78 and HSL79, and promotes the transcriptional downregulation of the ATGL inhibitors G0S2 and fat-specific protein-27 (FSP27; in humans designated cell-death-inducing DNA fragment factor 40/45-like effector C, CIDEC)80,81. This combination of effects results in a robust induction of lipolysis. The MAP kinase pathway was recently also shown to activate ERK-3 in response to β-adrenergic stimulation. This atypical member of the MAP kinase family increases forkhead box protein O-1 (FOXO1)-mediated ATGL transcription and stimulates lipolysis82.

Activin B83, growth/differentiation factor-3 (GDF-3)84, myostatin (also called GDF-8)85, bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-486 and BMP-7 (ref. 87) belong to the TGF-β family of cytokines and growth factors that regulate lipolysis. GDF-3 and activin B bind to activin-receptor-1c (also called activin receptor like kinase 7, Alk7) leading to the phosphorylation of SMAD transcription factors, which in turn, inhibit CEBPα and PPARγ expression and thereby decrease lipase gene transcription67. Concomitantly, the Alk7-dependent pathway also downregulates β3-adrenergic receptor expression leading to a reduction of catecholamine-induced lipolysis88. In contrast to GDF-3 and activin B, myostatin inhibits lipolysis in adipose tissue via binding to activin type-II receptors. Attenuation of lipolysis by myostatin appears to be due to a general impairment of anabolic pathways in lipid metabolism, decreased adipocyte differentiation as well as proliferation85,89. These observations may explain the findings that blockade of myostatin signalling is associated with decreased fat mass in fish, mice and humans, despite increased ERK1/2-mediated HSL phosphorylation90. The molecular mechanisms of other classical prolipolytic inflammatory cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα), interleukin-1β (IL-1β) or interleukin-6 (IL-6), remain poorly characterized and mostly affect lipolysis by indirect mechanisms91.

Transcription factor FOXO1 is the key factor in insulin-mediated downregulation of Pnpla2 gene expression92. FOXO1 binds directly to the promoter of Pnpla2 to induce its expression93. The transactivating function of FOXO1 is predominantly controlled by its modification status: phosphorylation determines its intracellular localization and acetylation regulates its activity. Insulin inhibits Pnpla2 transcription by the protein kinase B (PKB)-catalysed phosphorylation of FOXO1, which leads to 14-3-3 protein interaction and cytoplasmic retention of the transcription factor94. In hepatocytes, CDK1-dependent phosphorylation of FOXO1 similarly suppresses ATGL expression by cytoplasmic retention of FOXO1. Consistent with this finding, hepatocyte-specific CDK1 deletion induces ATGL-mediated hepatic fat degradation95. In contrast, interaction of 14-3-3 proteins with FOXO1 is inhibited by the AMPK-dependent phosphorylation of Ser22 of FOXO1, which enables translocation of this protein to the nucleus96. The other inhibitory post-translational modification of FOXO1, namely lysine acetylation by cAMP-responsive element binding protein (CBP)/p300, diminishes DNA binding of the transcription factor97. Histone deacetylases, including the NAD+-dependent sirtuins (SIRT)-1 and SIRT6, reverse this inhibitory effect and restore expression of target genes, including Pnpla2 (refs. 98,99). A reciprocal feedback is plausible given the fact that SIRT1 regulates ATGL via FOXO1, and ATGL also activates SIRT1, thereby affecting the transcription of genes involved in autophagy32,33. In addition to FOXO1, insulin inhibits lipolysis via the Zn-finger transcription factor SNAIL1. In adipocytes, insulin increases SNAIL1 expression, which binds to E2-box sequences in the Pnpla2 promoter and represses its transcription100.

Finally, lipolysis is inhibited by the key serine/threonine protein kinase, mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR). mTOR is embedded in two larger protein complexes named mTORC1 and mTORC2. mTORC1 activity is predominantly regulated by essential amino acids and induces cell growth and proliferation by the induction of protein, lipid and nucleic acid biosynthesis. mTORC1 inhibition by rapamycin or deletion of the regulatory-associated protein of mTOR (Raptor) induces lipolysis in an ATGL-dependent manner in cells and mice101,102,103. The underlying mechanisms include an upregulation of ATGL transcription by the transcription factor early growth response protein-1 (EGR1)104 as well as post-transcriptional mechanisms102. mTORC2 is a major regulator of the insulin/insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signalling pathway by phosphorylating AKT/PKB, controlling various aspects of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism as well as autophagy and cell survival105. mTORC2 inhibits lipolysis in adipose tissue and amplifies the antilipolytic function of insulin by phosphorylating AKT106,107. Moreover, and independently of the canonical mTORC2–AKT axis, rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR (Rictor) deletion leads to an induction of lipolysis via SIRT6-mediated deacetylation of FOXO1, and induction of ATGL expression99. Further studies are needed to clarify how mTORC2 affects SIRT6 activity.

Regulation of lipases by post-translational modifications

The canonical activation pathway of lipolysis in adipocytes involves the binding of catecholamines to β-adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptors. Upon hormone binding, the α-subunit of the receptor-coupled trimeric Gs protein dissociates and stimulates adenylate cyclase, resulting in cAMP synthesis108. Very recently, a new G-protein-coupled receptor was identified that constitutively activates adenylate cyclase in brown adipose tissue independently of ligand binding109. cAMP activates protein kinase A (PKA), which phosphorylates HSL (at residues S552, S649 and S650) and perilipin-1, a key player in the regulation of lipolysis (at residues S81, S222, S276, S433, S492 and S517)110. Phosphorylation results in HSL translocation to the LD and activation of the enzyme’s hydrolytic activity. PKA is not the only protein kinase phosphorylating HSL and perilipin-1. Atrial natriuretic peptides via guanyl-cyclase-derived cGMP activate protein kinase G, which phosphorylates both proteins at the same sites as PKA111. HSL is additionally phosphorylated (S600) and activated by ERK1/2 in response to mitogens, growth factors or cytokine signalling via the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway79. Perilipin-1 phosphorylation is required for HSL translocation, but also triggers its dissociation from CGI-58, thereby enabling CGI-58 to interact with ATGL and to activate enzyme activity112 (Fig. 3). The central role of perilipin-1 in the regulation of ATGL in humans became evident when Gandotra et al.113 reported that mutations in perilipin-1 lead to its inability to bind to CGI-58. This inability of perilipin-1 to buffer CGI-58 during basal lipolysis results in the constitutive hyperactivation of ATGL, unrestrained lipolysis, hyperlipidemia and fatty liver disease113,114.

Lipolysis is stimulated by activation of β-adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptors (β-AR). Binding of noradrenalin (NA), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) or secretin leads to dissociation of the receptor-coupled trimeric Gs protein and stimulation of adenylate cyclase (AC), resulting in cAMP synthesis. cAMP activates protein kinase A (PKA), which phosphorylates HSL and PLIN1. HSL translocates to LDs upon phosphorylation by PKA, protein kinase G (PKG) or ERK1/2. PLIN1 sequesters CGI-58, which is released upon PKA- or PKG-mediated phosphorylation to stimulate ATGL activity. PKG is activated by atrial natriuretic peptides (ANPs) via GC-derived cGMP. Enzymatic activity of ATGL is enhanced by CGI-58 and inhibited by G0S2 and HILPDA. FABP4 interacts with CGI-58 to further stimulate ATGL activity. Lipolysis is inhibited by insulin or insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) via insulin receptor or IGF receptor. Ligand binding subsequently activates insulin receptor substrate-1, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase, PDK1 and PKB, which activates PDE3B, resulting in the hydrolysis of cAMP. Lipolysis is also inhibited by adenosine, which decreases cAMP levels by activation of α-adrenergic receptors (AA1R) coupled with Gi proteins, inhibiting adenylate cyclase and cAMP synthesis.

In cell types with high oxidation rates, such as hepatocytes or cardiomyocytes, perilipin-5 coordinates the interaction of ATGL with CGI-58. Perilipin-5, unlike perilipin-1, is able to bind both ATGL and CGI-58, but the binding is mutually exclusive114,115. According to current understanding, two perilipin-5 molecules bound to ATGL and CGI-58, respectively, need to oligomerize to enable ATGL activation116. Perilipin-5 interaction with ATGL depends on the PKA-mediated phosphorylation of S155 in perilipin-5 (refs. 117,118). Interestingly, hormone-stimulated ATGL binding to perilipin-5 also promotes the translocation of FAs to the nucleus, where they act as allosteric activators of SIRT1 (ref. 33). This NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase subsequently deacetylates specific transcription factors, including PGC-1, to increase the expression of OXPHOS genes. Overall, however, the impact of perilipin-5 on lipolysis appears more modulatory than necessary, since periplipin-5-deficient mice exhibit elevated lipolysis119, while overexpression of perilipin-5 leads to reduced lipolysis and a steatotic phenotype in transgenic mice120. In contrast to perilipin-1 and perilipin-5, the impact of perilipin-2, perilipin-3 and perilipin-4 on regulation of hormone-stimulated lipolysis is not well understood and may be less prominent110,121.

Insulin and IGFs represent the predominant inhibitory hormones of lipolysis. They diminish both activity and gene expression of lipolytic enzymes122. The dominant pathway to inhibit enzyme activities involves the deactivation of the cAMP–PKA–pathway. Insulin, via the classical phosphatidylinositol-3 (PI3)-kinase-dependent signalling pathway, stimulates phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK1) and AKT/PKB, which activates phosphodiesterase 3B (PDE3B), resulting in the hydrolysis of cAMP, inactivation of PKA and consecutive downregulation of HSL and perilipin phosphorylation123. Interestingly, this process requires PDE3B interaction with ABHD15 (ref. 124), but is independent of PDE3B phosphorylation by PKB123. Another mechanism inhibiting lipolysis involves the activation of α-adrenergic receptors coupled with Gi-proteins by adenosine, which inhibits adenylate cyclase and cAMP synthesis125 (Fig. 3).

High cellular AMP concentrations during fasting or prolonged exercise induce ATGL gene transcription via AMPK dependent phosphorylation of FOXO1 (see section on transcriptional control). Whether AMPK also activates lipolysis by directly phosphorylating ATGL and HSL remains controversial. Both enzymes are AMPK phosphorylation targets (ATGL-S406 and HSL-S554). However, while AMPK-catalysed ATGL phosphorylation increases its activity12, HSL phosphorylation has an inhibitory effect. Whether AMPK stimulates or inhibits lipolysis may therefore strongly depend on specific experimental conditions leading to different results in various studies126. Also, the finding that adipose-specific deletion of AMPK has no effect on TG hydrolysis argues against a prominent role of AMPK in the regulation of lipolysis127. Notably, however, a recent report demonstrated that lipolysis activates AMPK128. Under hormonal stimulation, excessive lipolysis leads to increased FA re-esterification within a futile cycle of TG hydrolysis and resynthesis. This process is quite energy demanding and results in accumulated AMP and the activation of AMPK. This, in turn, causes mTORC1 inactivation and cellular growth arrest, a mechanism that may explain the inhibitory effect of lipolysis on cancer cell growth128,129. These results are also consistent with the finding that enhancing AMPK activity by an AMPK-stabilizing peptide reduces adipose tissue atrophy in cancer-associated cachexia130.

Peptide-coregulators of ATGL

CGI-58 (ABHD-5)

LD-bound ATGL requires a protein coactivator called comparative gene identification-58 (CGI-58) or α/β hydrolase domain-containing-5 (ABHD-5) for full enzyme activity9. Human CGI-58 is a protein of 349 amino acids that belongs to a family of 17 ABHD proteins, most of which are lipid hydrolases131. CGI-58 is an exception because it lacks the nucleophilic amino acid residue in the catalytic triad of the active site that is essential for functional hydrolases132. Unfortunately, molecular details concerning the actual activation mechanism are still unknown and will likely require three-dimensional structural information for both proteins. Phylogenetic and mutational analyses revealed that the highly conserved amino acid residues R299 and G328 in human CGI-58 are essential for ATGL activation133. Importantly, the Grannemann group developed a small-molecule inhibitor that disrupts the interaction of perilipin-1 and CGI-58. In the presence of this inhibitor, CGI-58 constitutively activates ATGL even in the absence of hormonal stimulation, which leads to unrestrained TG degradation134.

While global ATGL-KO mice die at the age of about 12 weeks from severe cardiomyopathy, CGI-58-deficient mice die within 24 hours of birth owing to trans-epithermal water loss and desiccation caused by a severe epidermal skin defect135. Absence of this phenotype in ATGL-deficient humans and mice argues strongly for an ATGL-independent epidermal function for CGI-58. In humans, mutations in the gene for CGI-58 cause an autosomal recessive skin disease designated NLSD with Ichthyosis (NLSDI)21,136. Since its original discovery in the 1970s, more than 100 cases of NLSDI have been reported. The disease is characterized by the accumulation of TGs in many tissues and severe ichthyosis137. Independent of ATGL, CGI-58 in keratinocytes interacts with and activates PNPLA1 transacylase activity driving acylceramide synthesis in the skin (see section on PNPLA1)138,139. CGI-58 also interacts with PNPLA3, the closest relative of ATGL within the PNPLA family (see below in section on PNPLA3)140. Other ATGL-independent functions of CGI-58 include an acyltransferase-141 and HDAC4-specific protease activity142. Whether these activities contribute to normal skin barrier function and the pathogenesis of NLSDI is currently not known.

G0S2

G0/G1 switch gene-2 (G0S2) is a 106-amino-acid protein that was originally described as a cell-cycle regulator mediating G0/G1 re-entry143. Like CGI-58, G0S2 turned out to be a multifunctional protein involved in cell proliferation, mitochondrial ATP production, apoptosis and cancer development144. Its best-characterized function, however, relates to its interaction and inhibition of ATGL145,146. Liu and colleagues elegantly demonstrated that G0S2 in mice and humans interacts via a hydrophobic stretch within the patatin domain of ATGL, thereby suppressing enzyme activity147. Non-cooperativity of G0S2 and CGI-58 suggest that the coregulators bind to ATGL at different sites. Oberer and colleagues developed a 33-amino-acid peptide ranging from K20 to A52 of human G0S2, including the hydrophobic ATGL interaction region, which inhibited ATGL with similar potency as full-length G0S2 (ref. 148). Both full-length G0S2 and the G0S2-derived peptide noncompetitively inhibit ATGL with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) in the nanomolar range. G0S2 specifically inhibits ATGL but fails to inhibit other lipid hydrolases of the PNPLA family or lipolytic enzymes148. In addition to its antilipolytic function, G0S2 may also have lysophosphatidyl-acyltransferase activity149.

G0S2 protein abundance is highest in adipose and relatively low in most other tissues. Fasting/feeding and nuclear receptor transcription factors PPARα and LXRα regulate G0S2 mRNA expression150,151. Consistent with the strong inhibitory effect of G0S2 on ATGL activity, its tissue-specific overexpression leads to steatosis in cardiac muscle or liver in mice152,153. Somewhat unexpectedly, G0S2-deficient mice exhibited a relatively modest phenotype with a slight increase in lipolysis and minor alterations in lipid and energy metabolism, as well as adipose tissue morphology154,155. The effect of G0S2 deficiency was more pronounced in the liver, resulting in decreased liver fat and resistance to high-fat-diet-induced hepatosteatosis156. The relatively low expression levels of G0S2 in mice may explain the lack of a major phenotype upon its deletion.

HILPDA

Hypoxia-induced lipid droplet-associated protein (HILPDA), also called hypoxia-induced gene-2 (HIG2), is a G0S2-related peptide of 63 amino acids that also inhibits ATGL activity. HILPDA was originally identified as an LD-binding protein that is highly expressed in response to hypoxia157. The promoter of the Hilpda gene harbours a number of hypoxia-responsive elements that are targeted by the transcription factors HIF-1 and HIF-2 (ref. 158). Like G0S2, Hilpda is a PPARα target gene159. HILPDA is abundantly expressed in immune cells, adipose tissue, liver and lung160. The protein binds to LDs and interacts with the N-terminal region of ATGL, thereby inhibiting ATGL activity in the absence or presence of CGI-58 (refs. 161,162). Compared with G0S2, however, human HILPDA is a much less potent ATGL inhibitor163. Independently of its effects on ATGL, murine HILPDA also interacts with the TG-synthesizing enzyme diacylglycerol-acyltransferase-1 (DGAT1) and promotes lipid synthesis in hepatocytes and adipocytes164. Despite these pronounced activities of HILPDA in vitro, the in vivo consequences of its deficiency in adipose tissue are very moderate. HILPDA deficiency affected neither plasma FA, glycerol or TG concentrations nor adipose tissue mass during fasting or cold exposure, apparently ruling out the possibility that HILPDA is a crucial regulator of lipolysis165,166. The generation of double-knockout mouse lines may clarify whether the benign phenotype of G0S2 or HILPDA deficiency results from mutual compensatory functions.

Other regulatory proteins of lipolysis

Lipase–protein interaction studies revealed a large number of factors that interact with ATGL, HSL or their respective coregulators. In addition to the already mentioned factors (ABHD-5, G0S2, HILPDA, ATGL-trafficking proteins, perilipins and CHREBP), at least a dozen factors have been described to affect lipolysis by direct lipase or coregulator binding. An overview of these factors was recently published by Hofer et al.167. They include the ATGL regulatory factors FSP27, pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) and 14-3-3 proteins or the HSL interaction partners fatty acid binding protein-4 (FABP4), vimentin and cavin-1. FABP4 also interacts with CGI-58 and plays an important role in the export of lipolysis-derived FAs or their transport to the cell nucleus34,168,169. Taken together, the lipolytic machinery represents a highly complex system composed of numerous factors, which we refer to as ‘lipolysome’.

Canonical enzymology of acid lipolysis

The only known neutral lipid hydrolase which is active under acidic conditions in lysosomes is LAL. This enzyme, originally discovered in 1968 (ref. 170), is responsible for the degradation of CEs, TGs, DGs and retinyl esters171,172,173 from lipoproteins and autophagosomes after their lysosomal uptake. LAL, encoded by the Lipa gene, is highly glycosylated and ubiquitously expressed, with highest levels observed in hepatocytes and macrophages. Several transcript variants of LAL have been described, of which a 288-amino-acid, 46-kDa protein exhibits the highest enzymatic activity174. The three-dimensional structure of the human enzyme was recently solved and revealed strong structural similarities to gastric lipase, another member of the acid lipase family175. Regulation of LAL activity is less complex than that of neutral lipases and involves primarily transcriptional mechanisms. Established transcription factors that activate LAL expression include PPARs, FOXO1 and the E-box transcription factors TFEB and TFE3 (ref. 176).

In addition to LAL’s lysosomal localization, small amounts of the enzyme are secreted via the classical secretory pathway into the blood177. Additionally, LAL is released from cells into the interstitium by a mechanism called exophagy, where the lysosomal membrane fuses with the plasma membrane, liberating the cargo178. The function of LAL (with a pH optimum of 4.5–5) outside lysosomes remains uncertain, but the enzyme may be able to hydrolyse lipids of aggregated or oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL) in an acidic extracellular microenvironment179,180. Conversely, cells can also internalize extracellular LAL. Enzyme exchange among different cell types and tissues explains the relatively mild phenotype of hepatocyte-specific LAL-KO mice181 and represents a potential treatment for people with Wolman’s disease by enzyme replacement therapy182 (see below).

LAL reaction products include non-esterified cholesterol and FAs. Cholesterol is subsequently released from lysosomes by an NPC1-dependent process and suppresses cholesterol de novo synthesis by multiple mechanisms183,184. Excess cholesterol is re-esterified and stored as CE in cytoplasmic LDs. The export mechanism for FAs is not well understood. After their liberation, they contribute to hepatic VLDL synthesis185, induce the alternative activation of macrophages186, represent precursors for highly bioactive lipid mediators187 and drive thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue188.

The role of lysosomes in the degradation of cargo derived from various endocytosed lipoproteins was recognized many decades ago. This function was extended when, in 2009, lipophagy was identified as a distinct form of autophagy and a quantitatively relevant mechanism for the hydrolysis of TGs and CEs in hepatocytes and macrophages189,190,191. Three types of autophagic pathways contribute to TG degradation: macrolipophagy, microlipophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA)192 (Fig. 4). During macrolipophagy, autophagosomes sequester and engulf parts of LDs and subsequently fuse with lysosomes to form autolysosomes189. In contrast, microlipophagy does not involve enclosure of LD components within autophagosomes. Instead, a direct flux of lipids occurs during transient docking of lysosomes to LDs by a ‘kiss and run’ mechanism193. Microlipophagy is a well-established process in yeast but has only recently been discovered in mammalian cells194. Interestingly, knockdown of ATGL in hepatocytes leads to reduced microlipophagy, indicating a connection between microlipophagy and neutral lipolysis194. A plausible explanation for this dependency is that ATGL activity reduces LD size, thereby rendering LDs more accessible for microlipophagy194,195. ATGL also plays an important role in CMA, in which the autophagosomal degradation of perilipins allows ATGL to access the surface of LDs and thereby stimulates lipolysis196. Heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) directly interacts with perilipin-2 and perilipin-3 on LDs by recognizing a pentapeptide motif197. It subsequently delivers them to lysosomes and facilitates their uptake and degradation, mediated by lysosome-associated membrane 2 (ref. 198). Mutation of Hsp70 binding motifs on perilipins leads to reduced CMA and LD accumulation in cultured cells and mouse livers in vivo, despite unaltered macroautophagy196.

Three types of autophagic pathways contribute to the degradation of cytosolic LDs. Macrolipophagy involves the microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3-II) dependent engulfment of parts of the LDs by ER membranes to form lipoautophagosomes which subsequently fuse with lysosomes to autolysosomes. During microlipophagy, Ras-related in brain (RAB) proteins facilitate the flux of lipids and proteins from LDs to the lysosome. Lysosomal acid lipase (LAL) is the only known lipase capable of hydrolysing neutral lipids under acidic conditions. Independent of LAL, chaperone-mediated authophagy facilitates a HSP70-mediated transfer and lysosome-associated membrane 2 (LAMP2) dependent lysosomal uptake and degradation of perilipins to increase the accessibility of cytosolic lipases to LDs.

LAL deficiency in mice leads to massive accumulation of CEs and TGs in the liver, intestine, adrenal glands and macrophages199,200. In humans, complete absence of LAL activity also provokes severe hepatosteatosis and hepato-splenomegaly. Unlike the murine model, however, the human deficiency, known as Wolman disease, is lethal within the first year after birth201. A more benign variant of the disease is called cholesteryl ester storage disease (CESD). People with CESD often, but not always, show some remnant LAL activity (1–10% of normal) and, depending on the severity of the disease, can reach a normal life expectancy202. People with CESD have a higher risk for atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease203. This phenotype is explained by increased lysosomal retention of CE in macrophages owing to low LAL activities leading to insufficient suppression of cholesterol de novo synthesis and foam-cell formation190. Several GWAS studies identified common polymorphisms in the Lipa gene that associate with cardiovascular diseases204. However, their impact on LAL function remains controversial.

Noncanonical enzymes and mechanisms of TG mobilization

The canonical lipases ATGL, HSL, MGL and LAL are the best-characterized enzymes with regard to hydrolysis of cytoplasmic TG stores. In adipose tissue, ATGL and HSL account for more than 90% of TG hydrolysis205, rendering the existence of other major lipases unlikely. In non-adipose tissues, however, substantial TG hydrolase activities are observed even in the absence of ATGL and HSL. In addition to a significant contribution of acid lipolysis, several alternative neutral lipases of diverse protein families have been connected to TG catabolism in the past decade (summarized in Table 1).

PNPLA family members

Although the critical role of ATGL in lipolysis is undisputed, the distinct biochemical functions of its most closely related family members—PNPLA1, PNPLA3, PNPLA4 and PNPLA5—remain equivocal. The presence of an α/β hydrolase fold and a catalytic dyad with an active site serine embedded in a GXSXG consensus sequence provide these proteins with the structural prerequisites to act as lipid hydrolases. While an unambiguous assignment of their primary physiological substrates is still missing, some of these enzymes are directly involved in disease development.

PNPLA1

PNPLA1 is a 446-amino-acid protein specifically expressed in differentiated keratinocytes of the skin206,207. It is an established causative gene for autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis (ARCI), which is characterized by a severe defect in the development of the epidermal corneocyte lipid envelope (CLE) and the transepithelial water barrier in the skin in humans and dogs208. The clinical presentation essentially phenocopies the deficiency of CGI-58 in the skin135, arguing for a common involvement of both proteins in the formation of the CLE. PNPLA1 is a transacylase that specifically transfers linoleic acid from TG to ω-hydroxy ceramide, thus giving rise to ω-O-acylceramides138,207. These skin-specific lipids are essential for the generation of the CLE and an intact skin permeability barrier. Transacylation of FAs requires a hydrolysis reaction that is coupled with an esterification reaction. CGI-58 interacts with PNPLA1 and recruits the enzyme onto cytosolic LDs where PNPLA1 utilizes TG-derived FAs for ω-hydroxy ceramide acylation138,139. PNPLA1 mutations leading to ARCI may additionally impair autophagy, arguing for a potential role of PNPLA1 in lipophagy-mediated degradation of LDs209.

PNPLA3

PNPLA3 (also named adiponutrin or calcium-independent phospholipase-A2ε) comprises 481 amino acids, is structurally closely related to ATGL (46% sequence homology), and highly abundant in white and brown adipose tissue of mice. In humans, PNPLA3 is less abundant in adipocytes, but highly expressed in hepatocytes210. Key transcription factors responsible for the expression of PNPLA3 include CHREBP in response to carbohydrates and SREBP1c in response to insulin211,212. PNPLA3 localizes to LDs213 and exhibits various enzymatic activities including TG-, DG-, MG- and retinyl ester hydrolase activity, PLA2 activity and transacylase activity8,214,215,216. It remains unclear which of these activities are physiologically relevant in adipose tissue and in the liver217.

The fact that PNPLA3-KO mice have essentially no abnormal phenotype with normal plasma and hepatic TG concentrations218,219 argued against a major role of PNPLA3 in lipid homeostasis. This view changed dramatically when Hobbs and colleagues reported that a single amino acid exchange at position 148 from isoleucine to methionine in PNPLA3 (p.I148M) strongly associates with NAFLD220. This association was replicated in numerous studies and extended to associations of the mutation with steatohepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma217. The I148M variant is frequent in populations of Hispanic descent (up to 50% of individuals), African Americans and Caucasians and is considered a key player in the pathogenesis of liver disease220.

Important progress concerning the function of PNPLA3 was achieved by recent studies suggesting that excess PNPLA3 on the surface of LDs competes with ATGL for its coactivator CGI-58 (refs. 140,221). PNPLA3-I148M has higher affinity to CGI-58 than does wild-type PNPLA3 (ref. 140). According to the current understanding, the high affinity of PNPLA3 for CGI-58 leads to a ‘coactivator steal’ since PNPLA3 retains CGI-58, keeping it from binding to ATGL. This leads to reduced ATGL activity, which may explain the fatty liver disease in people carrying the variant. Additionally, the I148M variant may promote increased TG synthesis via a transacylation reaction216. Finally, PNPLA3-I148M’s resistance to proteasomal222 and autophagy-dependent223 protein degradation, compared with that of wild-type PNPLA3, potentially amplifies the impact of the mutant protein on lipid homeostasis.

PNPLA4

PNPLA4 was originally identified as gene sequence 2 (GS2) in the human genome224 and is also found in other mammalian species but not in mice225. The PNPLA4 gene is located on the X chromosome between the genes encoding steroid sulfatase and Kallmann Syndrome-1. The human PNPLA4 protein comprises 253 amino acids and is expressed in numerous tissues, including adipose tissue, skeletal and cardiac muscle, kidney, liver and skin225,226. Similar to PNPLA3, various enzymatic activities have been attributed to PNPLA4, including TG and retinyl ester hydrolase, phospholipase and transacylase activities8,225,226. Genetic analyses have suggested that PNPLA4 is involved in the development of two rare congenital disorders: combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency (COXPD) and X-linked intellectual disability227,228. COXPD arises from a hemizygous nonsense mutation resulting in a C-terminally-truncated protein (R187ter) and defective assembly of complexes I, III and IV of the respiratory electron transport chain. Whether the enzymatic activity of PNPLA4 is involved in the pathogenesis of COXPD is unknown. Fortunately, small-molecule inhibitors have recently been developed that may help to elucidate the biochemical function of PNPL4 and its role in (patho-)physiology229.

PNPLA5

PNPLA5 (also named GS2-like) is a 429-amino-acid protein that is ubiquitously expressed and, unlike PNPLA4, is present in both mice and humans210. Its expression is induced during adipocyte differentiation and in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice, and is inhibited by fasting225. PNPLA5 exerts hydrolytic activities towards multiple lipid substrates, including TGs and retinyl esters, but has also been shown to exhibit transacylase activity225,230. Notably, PNPLA5-dependent hydrolysis of LD-associated TGs has been suggested to affect autophagosome biogenesis231. Furthermore, rare variants of PNPLA5 strongly associate with LDL cholesterol levels in humans232. To date, it remains unclarified whether the lipid hydrolase/transacylase activity or its participation in lipophagy has a functional role in the regulation of plasma LDL cholesterol levels.

Carboxyl esterase family members involved in lipolysis

Mammalian carboxylesterases (CESs) belong to a multigene, α/β-hydrolase fold superfamily encoding 6 human and 20 mouse paralogs. They catalyse the hydrolysis of a wide range of endogenous substrates and xenobiotics233. CES family members that exhibit neutral TG hydrolase activity include human CES1 (also called human cholesterylesterhydrolase-1, hCEH) and CES2, and mouse Ces1d (also called Ces3 or TG hydrolase-1), Ces1g (also called Ces1 or esterase-X) and Ces1c. The previously confusing nomenclature of human and murine CES enzymes has recently been revised for more clarity234.

Human and mouse carboxylesterases 1

The carboxylesterase 1 (CES1) gene in the human genome encodes a 62-kDa protein with high abundance in liver and intestine and lower abundance in kidney, adipose tissue, heart and macrophages233,235. The active site of the monomeric, dimeric or trimeric enzyme consists of a catalytic triad within an α/β-hydrolase fold235. CES1 preferably hydrolyses CEs and TGs236,237. Hepatocyte-specific overexpression of human CES1 in transgenic mice increases hepatic TG hydrolase activity; lowers TG, FA and cholesterol content; and reduces reactive oxygen species (ROS), apoptosis and inflammation, which cumulatively protect mice from western-diet- or alcohol-induced steatohepatitis238. Both hepatocyte-239 and macrophage-specific240 overexpression of CES1 in mice decrease atherosclerosis susceptibility in LDL-receptor-deficient mice and, consistent with this finding, treatment of THP-1 macrophages with a CES1 inhibitor caused accumulation of CE241. Another study, however, failed to observe neutral CE hydrolase activity of recombinant CES1 and saw no effects of CES1 overexpression or silencing on cellular cholesterol/CE homeostasis242. Hence, the role of human CES1 in lipid metabolism remains controversial.

Murine Ces1d (also termed triacylglycerol hydrolase-1 (Tgh-1) or Ces3) is a TG hydrolase with 74% sequence identity to human CES1. Ces1d is highly expressed in adipose tissue and liver243 where it localizes to the lumen of the ER244. In adipose tissue, Ces1d is additionally associated with LDs and may contribute to basal lipolysis245,246. In mouse hepatocytes, transgenic overexpression or pharmacological inhibition of Ces1d increased or decreased VLDL assembly and secretion, respectively247,248,249. In accordance with these findings, liver-specific and global Ces1d deficiency in mice lowers VLDL production and plasma TG and CE concentrations250,251. Despite strong evidence for a role of Ces1d in hepatic VLDL assembly and secretion, it remains unclear how an enzyme residing in the lumen of the ER actually contributes mechanistically to lipoprotein synthesis. Interestingly, while global Ces1d deficiency leads to TG accumulation in isolated hepatocytes, conditional Ces1d knockout in liver cells does not. In fact, they are actually protected from high-fat-diet-induced hepatic steatosis251,252. The protective effect of Ces1d deficiency in the liver might be due to reduced FA-synthase activity and increased hepatic FA oxidation250,252. Moreover, mice with global, but not liver-specific, Ces1d deficiency exhibit improved insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance250,251. The recent finding that Ces1d deficiency does not affect CE hydrolysis or bile-acid synthesis in mice253 argues against an important role for CES1 enzymes in cholesterol homeostasis (see previous paragraph).

The second murine ortholog to human CES1 with established TG hydrolase activity is Ces1g. This enzyme is mainly expressed in liver and shows 76% sequence homology with Ces1d. Overexpression of Ces1g increases TG hydrolase activity and reduces TG content in cultured rat hepatoma cells and livers of transgenic mice254,255. Conversely, global- and liver-specific Ces1g-KO mice exhibit hepatic steatosis and hyperlipidemia255,256. Restoration of hepatic Ces1g expression reverses hepatic steatosis, hyperlipidemia and insulin resistance in global Ces1g-deficient mice257. Several studies suggest that the lipid phenotype observed in Ces1g-deficient mice results from diminished FA signalling to restrain SREBP1c activation, leading to reduced FA oxidation and increased de novo lipogenesis255,256,257.

Human and mouse carboxylesterases 2

Human CES2 is a monomeric 62-kDa protein that shares 47% amino acid sequence identity with CES1 and 71% homology with murine ortholog Ces2c. CES2 preferably hydrolyses esters with a large alcohol group and a small acyl group, and as for Ces2c, TG and DG hydrolase activities have been reported258,259. CES2 is abundantly expressed in the small intestine, colon and liver and is decreased in mice and humans with obesity and NAFLD235,258,259. Adenoviral overexpression of human CES2 in the liver of mice prevents genetic- and diet-induced steatohepatitis by increasing TG hydrolase activity and FA oxidation and reduces SREBP1c mediated lipogenesis, inflammation, apoptosis and fibrosis.259,260.

Murine Ces2c is a highly abundant TG, DG and MG hydrolase in liver and intestine258,261. Its expression is decreased in livers of mice with diet- or genetically induced obesity258,261. Loss of hepatic Ces2c in chow- or western-diet-fed mice causes hepatic steatosis258. Conversely, increasing hepatic Ces2c expression ameliorated obesity and hepatic steatosis, and improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity258. Mechanistically, FAs released by Ces2c enter FA oxidation and concomitantly inhibit SREBP1 activity to decrease de novo lipogenesis in the liver258. Similarly, intestine-specific transgenic expression of Ces2c in mice also promotes intestinal TG hydrolysis and FA oxidation, and ameliorates high-fat-diet-induced obesity and NAFLD262. Moreover, an increased re-esterification rate of MGs and DGs may contribute to the generation of large chylomicrons that undergo accelerated postprandial TG clearance262. Taken together, the physiological function of both human CES2 and murine Ces2c render this enzyme an attractive target for the treatment of metabolic liver disease.

Lipid-droplet-associated hydrolase

Lipid-droplet-associated hydrolase (LDAH) is another member of the α/β-hydrolase superfamily with predicted lipase activity but unclear function. The putative enzyme is mainly expressed in BAT, WAT, liver, heart and macrophages of atherosclerotic lesions263. LDAH harbours a GXSXG lipase motif within an α/β-hydrolase fold and a hydrophobic motif that anchors the protein to cytosolic LDs263,264,265. While LDAH’s localization to LDs is undisputed in multiple cell models, enzymatic activity and biological function of the protein remain unknown. The LDAH ortholog in D. melanogaster (CG9186) facilitates lipid packaging and regulates LD clustering in cell and tissue cultures of salivary glands264,266. Unfortunately, only conflicting data exist on the physiological function of the enzyme in mammalian cells. Goo et al.263 demonstrated that overexpression of human or mouse LDAH in human embryonic kidney cells or RAW-macrophages elevates CE turnover and cholesterol efflux, while silencing of the enzyme causes CE accumulation. The same group also showed that LDAH promotes LD accumulation by affecting ATGL ubiquitinylation and degradation267. In other studies, however, LDAH overexpression did not affect CE, TG and retinyl ester hydrolase activity, and LDAH ablation did not change CE turnover in bone-marrow-derived macrophages265. Also, mice globally lacking LDAH exhibit normal CE, TG and whole-body energy metabolism, suggesting that LDAH either plays only a minor role in lipid metabolism or when absent is replaced by effective compensatory mechanisms265. Notably, genetic studies revealed that loss of LDAH may be associated with prostate cancer and sensorineural hearing loss268. Without a better functional characterization of this putative lipase, it is currently impossible to assess its role in lipid and energy homeostasis or cancer development.

DDH domain-containing protein 2

DDH domain-containing protein 2 (DDHD2, also named KIAA0725 or iPLA1γ) belongs to the mammalian intracellular phospholipase A1 (iPLA1) family which consists of three paralogs—DDHD1, DDHD2 and SEC23IP. All members share a conserved GXSXG lipase motif and a DDHD domain named after a characteristic amino acid signature within the domain269,270. DDHD2 exhibits DG and TG hydrolase activity, and DDHD2 deficiency in mice causes TG accumulation in the brain271,272,273,274. The human DDHD2 gene encodes a 711-amino-acid protein with a molecular weight of 81 kDa. The protein localizes to the cytosol, Golgi apparatus and ER274,275. In humans, loss-of-function mutations in DDHD2 lead to hereditary spastic paraplegia276,277,278, a neurodegenerative disorder associated with lipid accumulation in the brain and characterized by spasticity in the lower limbs276. Putative DDHD2-dependent mechanisms that may underlie hereditary spastic paraplegia include (1) the accrual of LDs, which would hinder protein and/or lipid trafficking required for synapse assembly276, (2) reduced cardiolipin biosynthesis and increased ROS production in mitochondria, which would trigger apoptosis of motor neurons in the spinal cord279 and (3) altered mobilization of FAs from LDs, which would affect membrane phospholipid composition and neuronal function280. Additionally, short-hairpin-RNA-mediated DDHD2 knockdown was shown to impair phospholipid synthesis and sensory axon regeneration after sciatic nerve crush281, emphasizing a crucial role for lipolysis in neuron function. Moreover, genome-wide analyses identified DDHD2 as a candidate risk gene for other neurological diseases, including autism and schizophrenia282,283. Whether these diseases are directly linked to the enzymatic activity of DDHD2 is currently investigated.

Arylacetamide deacetylase

Arylacetamide deacetylase (AADAC) is a 45-kDa esterase that harbours a typical GXSXG motif and exhibits considerable sequence homology to HSL in its presumed active site284. AADAC localizes to the ER and is mainly expressed in liver and intestine with much lower expression in adrenal glands and pancreas284,285. AADAC preferably hydrolyses cholesteryl acetate and DGs over TGs286,287. Its diurnal expression pattern is identical to hepatic VLDL secretion in mice and depends on transcriptional regulation by PPARα (ref. 285). Overexpression of AADAC in human (HepG2) and rat (McA) hepatoma cells increases TG secretion and reduces TG accumulation, respectively, indicating that it might play a role in lipid mobilization for VLDL synthesis286,288. Another study has demonstrated that, although hepatic AADAC activity is decreased in humans with obesity, there was no association to the homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) index or with DG species, and knockdown of endogenous AADAC did not affect FA oxidation in primary human hepatocytes259. Accordingly, the role of AADAC in lipid metabolism in vivo is still elusive.

Exosome-mediated TG mobilization

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) represent a recently discovered mechanism for the utilization of TG stores. In contrast to lipolysis and lipophagy, EV-mediated TG utilization does not involve TG hydrolysis and subsequent FA distribution. Instead, LDs are directly released from cells within EVs. A familiar, unique subclass of EVs containing large amounts of TGs are milk fat globules. They originate from cuboidal epithelial cells of lactating mammary glands and are secreted into milk ducts289. Apart from the very distinct milk fat globules, EVs are generally secreted from almost all cell types and are found in interstitial fluid and many other body fluids. The term EV subsumes two major types of vesicles, which differ in size and origin: (1) exosomes, which are 30–150 nm in diameter and originate from intraluminal vesicles of the endosomal system and (2) microvesicles, which are 100- to 1,000-nm structures blebbing off the plasma membrane290. After their release, EVs are internalized by other cells, enabling the horizontal transfer of cargo from donor to recipient cells. The nature of their cargo is manifold and includes proteins, nucleic acids, various metabolites and even intact organelles290. EVs have thus been attributed diverse biological functions ranging from immunomodulation to tissue differentiation and cancer development291.

Importantly, Ferrante and colleagues reported that adipocyte-derived EVs are able to transport TGs to adipose-tissue-resident macrophages292. Similar to all EVs, TG-containing exosomes are enclosed by a phospholipid bilayer derived from the plasma membrane of EV-producing cells292. Additionally, a phospholipid monolayer engulfs the hydrophobic core of enclosed LDs292 (Fig. 5). Ex vivo experiments have demonstrated that mobilization of TGs via exosomes accounts for up to 2% of the cellular lipid release per day, independent of canonical FA mobilization by lipolysis. Adipocyte-derived exosomes are almost exclusively taken up by macrophages and may thus represent an alternative pathway for local intercellular lipid distribution in adipose tissue. Through this process, macrophages may adapt to their local adipose tissue environment, consistent with similar findings in other tissues292. Whether adipocyte-derived EVs can transport TG cargo to cells and tissues other than macrophages remains to be elucidated.

Sebocytes represent another cell type secreting large amounts of mostly neutral lipids including TGs. These lipids accumulate in LDs during sebocyte differentiation but in contrast to adipocytes, lipid mobilization occurs via sebocyte necrosis instead of lipolysis or exosome-mediated pathways293. Interestingly, Kanbayashi and colleagues294 recently discovered an immune–metabolic signalling axis whereby thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) induces hypersecretion of sebum via CD4+ and CD8+ T cell activation. Sebum hypersecretion is associated with increased fat catabolism in adipose tissue and associated with adipose tissue loss in a TSLP transgenic mouse model.

Therapeutic potential of lipolysis inhibition

Considering the essential role of lipolytic enzymes in systemic and tissue-specific energy homeostasis, the inhibition of lipolysis may offer potential treatment opportunities for various metabolic, and possibly even infectious, diseases. Example target diseases are described below and in Box 1.

Type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes is a serious public-health concern that impairs quality and expectancy of life. Obesity represents the major risk factor for type 2 diabetes295. It is well accepted that an increased FA flux from hypertrophic adipose tissue to insulin-sensitive tissues contributes to insulin resistance and glucose intolerance296. Accordingly, reduced FA mobilization from adipose tissue in mice with global or adipocyte-specific deletion of ATGL, HSL or LAL leads to significantly increased glucose tolerance and improved insulin sensitivity24,27,185,297,298,299. For HSL deficiency, the beneficial metabolic phenotype is present in old, but not young, mice, and may be due to a concomitant decline in ATGL activity, which strongly impairs FA mobilization from adipose stores in older animals40. Interestingly, HSL deficiency in humans leads to insulin resistance, arguing for considerable species-specific differences in HSL’s role in controlling carbohydrate metabolism. Pharmacological inhibition of ATGL300 or HSL301 also improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in high-fat-diet-fed mice. A shift towards glucose utilization upon reduced FA availability from adipose tissue, reduced hepatic acetyl-CoA levels and pyruvate carboxylase activity and, consequently, reduced hepatic glucose production contributes to increased glucose tolerance in mice with adipocyte-specific ATGL deficiency302.

Hypoinsulinemia occurs in both ATGL- and HSL-deficient mice and likely contributes to the insulin-sensitive phenotype27,298,300,301. Insulin, secreted from pancreatic β-cells, regulates lipid versus carbohydrate utilization as fuel for energy. β-cell-intrinsic lipolysis generates various lipid intermediates with signalling potential like MGs, FA-CoAs and FAs that were shown to regulate glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS)303. Studies in global- and β-cell-specific ATGL and HSL-deficient mice revealed impaired GSIS of isolated pancreatic islets and hypoinsulinemia26,31,304,305,306,307. In contrast, inhibition of LAL in pancreatic β-cells indirectly potentiates GSIS by activating ATGL and HSL308. Several mechanisms have been proposed for impaired insulin secretion in ATGL-deficient β-cells, including (1) reduced availability of PPARδ ligands resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction31, (2) reduced generation of MGs that induce insulin exocytosis by binding to the vesicle priming protein Munc13–1 (refs. 26,309) or (3) reduced palmitoylation and stability of SNARE protein syntaxin 1a (Stx1a), which is crucial for insulin secretion305. Moreover, FAs liberated from adipose tissue promote insulin secretion after β-adrenergic stimulation310 and reduced or diminished adipocyte ATGL or HSL activity perturbs insulin secretion from β-cells27,298,299,300,311. Hence, specifically manipulating adipocyte lipolysis may represent a potential pharmacological approach to improve insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance.

Fatty liver disease

NAFLD affects approximately 25% of the global population312. In around 10% of all cases, NAFLD progresses from relatively benign hepatic steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which can further evolve to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)313. Obesity-associated NAFLD results from either increased de novo TG synthesis in the liver or increased flux of FAs from adipose tissue to the liver, or both314. Accordingly, reduced FA mobilization from adipocytes ameliorates hepatic steatosis, inflammation and fibrosis in high-fat-diet-fed mice that have adipocyte-specific ATGL deficiency or CGI-58 deficiency or that have been treated with atglistatin298,300,315. Somewhat counterintuitively, overexpression of ATGL in adipocytes also improves hepatic steatosis in a transgenic mouse model316. However, evidence shows that enhanced FA oxidation in adipose tissues of adipocyte-specific ATGL transgenic mice reduces FA flux to the liver, resulting in decreased hepatic fat storage.

Numerous GWAS and candidate-gene studies have demonstrated that the PNPLA3-I148M variant represents a strong genetic risk factor for steatohepatitis, fibrosis and HCC220. ASO-mediated silencing of PNPLA3 improved NAFLD and fibrosis in a mutant knock-in mouse model harbouring the PNPLA3-I148M mutation317. Therapeutic interventions that lower PNPLA3-I148M protein levels, such as SREBP1C inhibitors or antisense/silencing approaches, are likely to be beneficial in ameliorating NAFLD318. Moreover, PNPLA3-I148M sequesters CGI-58 from its interaction with ATGL and impairs its hydrolytic activity for LD-associated TGs139. Disrupting the interaction of PNPLA3 with CGI-58 by small molecules, as already reported for the CGI-58/perilipin-1 interaction134, may offer a potent therapeutic strategy to restore hepatic TG hydrolysis and prevent NAFLD in carriers of the I148M variant134. This therapeutic concept is corroborated by the finding that diet-induced hepatic steatosis is prevented by adenovirus-mediated overexpression of ATGL in murine livers319.

Heart failure

Chronic heart failure (HF) is a common disease resulting from any structural or functional impairment of ventricular filling or ejection of blood320. HF represents a leading cause of death and can basically be subdivided into two distinct groups: HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and HF with restricted ejection fraction (HFrEF)320. In developed countries, the prevalence of HF in the adult population is about 1–2%, and the 5-year mortality rate reaches up to 75% of people with the condition321. HFpEF, which comprises around 50% of HF cases, is often associated with metabolic disorders such as obesity, diabetes and hypertension321. The healthy heart exhibits high flexibility to use FA, glucose and ketone bodies as energy substrates322. During cardiac failure, metabolic flexibility is reduced, and the heart increasingly uses glucose as energy fuel322. However, a chronic activation of the sympathetic nervous system and an increase in natriuretic peptides augments adipose FA mobilization, which competes with glucose utilization and aggravates oxidative stress during HF323,324,325. Accordingly, adipocyte-specific ATGL deficiency or atglistatin treatment protected mice from pressure-induced cardiac hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis326,327. Similarly, ATGL inhibition promoted a cardioprotective effect in a mouse model of catecholamine-induced cardiac damage328. It has been suggested that inhibition of adipocyte ATGL activity improves cardiac energy metabolism by further shifting substrate utilization from FAs towards glucose and by changing the cardiac membrane lipid composition329. Future studies will address the potential of ATGL inhibition in ‘metabolic’ models of HFpEF, such as the hypertensive mouse fed a high-fat diet330. Considering the current lack of effective therapeutics, the pharmacological inhibition of ATGL, and possibly other lipases in adipose tissue, may represent a promising approach to treat HFpEF. Importantly, however, the inhibition of lipolysis must be restricted to adipose tissue because concomitant suppression of lipolysis in cardiac myocytes, hepatocytes and other non-adipose tissues may result in steatosis and organ dysfunction, as present in people with global ATGL21,23 or CGI-58 deficiency136.

Cachexia

Cachexia is a severe wasting disorder accompanying the late stage of various diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, burn-induced trauma or cancer331. The occurrence of cachexia in any of these maladies drastically decreases treatment options and chances of survival. Cachexia is a hypermetabolic disorder characterized by systemic inflammation and an unintended loss of body weight due to a reduction in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle mass that cannot be reversed by increased nutritional intake331,332. To date, the multifactorial mechanisms causing cachexia are yet insufficiently understood and effective treatments are not available. Adipose tissue loss often precedes muscle loss in cachexia, and some studies have provided evidence that halting fat depletion also preserves muscle mass333,334. Hence, recent studies engage a more ’adipocentric’ view of cachexia development335. Mechanistically, adipose tissue undergoes a switch towards catabolism that is initiated by proinflammatory cytokines and amplified by β-adrenergic signals336,337. This catabolic reprogramming elevates lipolysis and futile cycling, but reduces lipogenesis and fat accumulation, leading to adipose tissue atrophy332,335. Reducing lipolysis by pharmacological or genetic inhibition of ATGL333,338 or by targeting the erroneously prolipolytic signals, like the β3-adrenergic signal336 or the AMPK–CIDEA axis130, prevented adipose-tissue loss in murine cachexia models of burn-induced trauma or cancer. Interestingly, ATGL blockade not only reduced lipolysis but also prevented browning of WAT and fatty-liver development post burn injury338 and muscle atrophy in some mouse models of cancer cachexia333. The mechanisms underlying the tumour–adipose tissue–muscle crosstalk in cachexia and the question of whether lipolysis inhibition affects cachexia in humans await future clarification.

Conclusion