Abstract

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) comprises a spectrum of chronic inflammatory manifestations affecting the axial skeleton and represents a challenge for diagnosis and treatment. Our objective was to generate a set of evidence-based recommendations for the management of axSpA for physicians, health professionals, rheumatologists and policy decision makers in Pan American League of Associations for Rheumatology (PANLAR) countries. Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation-ADOLOPMENT methodology was used to adapt existing recommendations after performing an independent systematic search and synthesis of the literature to update the evidence. A working group consisting of rheumatologists, epidemiologists and patient representatives from countries within the Americas prioritized 13 topics relevant to the context of these countries for the management of axSpA. This Evidence-Based Guideline article reports 13 recommendations addressing therapeutic targets, the use of NSAIDs and glucocorticoids, treatment with DMARDs (including conventional synthetic, biologic and targeted synthetic DMARDs), therapeutic failure, optimization of the use of biologic DMARDs, the use of drugs for extra-musculoskeletal manifestations of axSpA, non-pharmacological interventions and the follow-up of patients with axSpA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

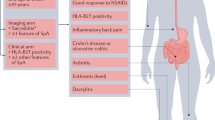

The term axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) comprises a spectrum of chronic inflammatory manifestations that mainly affect the axial skeleton (vertebral spine and sacroiliac joints), together with additional extra-musculoskeletal manifestations such as uveitis, psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It includes the spectrum of patients with radiographic sacroiliitis (ankylosing spondylitis (AS) or radiographic axSpA (r-axSpA)) and without radiographic sacroiliitis (non-radiographic axSpA (nr-axSpA))1,2. The main symptom of the disease is chronic low back pain, with inflammatory characteristics such as morning stiffness predominating in the second half of the night, that improves with exercise. Other musculoskeletal manifestations are arthritis, enthesitis and dactylitis. Peripheral manifestations such as arthritis and enthesitis have been reported more frequently in Latin America than in Europe or the USA3,4.

The global prevalence of axSpA varies substantially in different published studies. A systematic literature review estimated that the global prevalence of AS varies from 0.14% in Latin America to 0.20% in North America and 0.25% in Europe5. However, other studies have reported an estimated prevalence of axSpA of up to 0.8% and a prevalence of AS between 0.2% and 0.9% in Latin America6. The differences in these findings are related mainly to demographic characteristics, case definitions, geographic regions and the methodological design of the different studies.

Patients with axSpA experience a substantial deterioration in health-related quality of life (QoL) on account of impaired function, work productivity and social interactions7. Similarly, axSpA has a negative effect on mental health that is associated with disease activity and employment status, with an increased risk of depression and anxiety in patients with axSpA compared with the general population8. Comorbidities also contribute to the burden of disease9,10, are frequent in patients with axSpA and are related to poor health conditions and increased disease severity11.

Early identification and adequate treatment are a priority in achieving the treatment goals of individuals with axSpA. These goals focus on maximizing health-related QoL by means of symptom and inflammation control, prevention of progressive structural damage, preservation of function and participation in social activities, together with maintaining the ability to work12.

The use of new therapies in axSpA requires continuous and regular evaluation of their role in disease management in specific contexts; factors related to health care systems, access to medical care and the availability of medicines substantially affect the attainment of successful outcomes. Therefore, recommendations for the management of axSpA need to involve the perspectives of diverse countries in any particular geographic region with a view to guiding treatment decision-making and reducing treatment variability. In this context, national recommendations have been published in different countries in the Americas13,14,15,16, thereby developing local management recommendations. In view of the variability in the management of axSpA in Latin America, there is a need to generate a common guideline through evidence-based recommendations that makes it possible to homogenize management practices in the Americas, adapted to the needs and the context of the Pan American League of Associations for Rheumatology (PANLAR) community and the socioeconomic challenges within the different countries in the region. Conversely, many PANLAR member countries have a limited number of rheumatologists, with few or none specialized in axSpA, thus preventing them from developing local guidelines. These countries will benefit from guidelines developed in the PANLAR region by local experts that might include those from their countries. There is some evidence that the inclusion of local opinion leaders is effective in improving the implementation of clinical guidelines17. Very rarely, experts from Latin America have participated in other guidelines intended to be international12,18.

The objective of this article is to present the first PANLAR-developed evidence-based recommendations for the management of axSpA and to describe how they were developed.

Methods

Full methodological details are included in the Supplementary Information. The main objective of the current recommendations is to provide an evidence-based framework to guide health care professionals who treat adults with axSpA, mainly focused on Latin American countries. The scope of the guidelines is limited to recommendations regarding the use of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments.

The target audience of these recommendations is health-care providers and stakeholders who are involved in the management of patients with axSpA. This group could include rheumatologists, internists, primary care providers or general practitioners, pharmacists, policy makers and physicians in other specialties who may find this information useful (for example, physiatrists and orthopaedists). The target audience might also include patients with a diagnosis of axSpA. These guidelines have been developed and endorsed by PANLAR, using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE)-ADOLOPMENT framework19 and abiding by the AGREE Reporting Checklist to ensure the completeness and transparency of reporting in practice guidelines20, in a process led by a GRADE methodologist expert group.

The working group that developed the recommendations was divided into three subgroups: a multidisciplinary panel of experts selected by the PANLAR Research Unit comprising 32 members (rheumatologists, epidemiologists and three patient representatives) with expertise in the field of axSpA and representing the majority of PANLAR countries; a team of three methodologists; and a central review committee made up of five members with clinical and methodological expertise (E.R.S., G.C., C.L., P.D.S.B. and E.S.). The members of the panel represent 15 countries of the Americas. All members of the working group disclosed their potential conflicts of interest before the start of the process. Relevant conflicts of interest were those occurring within 12 months prior to and during the development of these guidelines.

Initially, the expert panel members defined the scope of the guidelines, selected the source guideline (ACR, Spondylitis Association of America (SAA) and Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network (SPARTAN) recommendations for the treatment of AS and nr-axSpA18), and generated PICO (population, intervention, comparator, outcomes) questions. The methodologists performed an independent systematic literature review to update the evidence supporting the ACR–SAA–SPARTAN guidelines, overseen by two members of the panel with expertise in methodology (M.L.B. and D.G.F.Á).

For the systematic literature search, the MEDLINE/PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE and LILACS databases were searched for randomized controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomized trials, cohort studies, post hoc analyses and pooled analyses published from the beginning of each database to November 2021. Abstracts presented at ACR, EULAR and PANLAR meetings since 2018 were also evaluated. The process of the literature search is summarized in the Supplementary Information, section C.

For study selection, two independent reviewers screened each title and abstract for duplicates, with a third reviewer resolving any potential conflicts. Eligible articles underwent full-text screening by two independent reviewers. Selected manuscripts were matched to the PICO questions (see Supplementary Information section D). With regard to data extraction and analysis, pooling of the data for statistical analysis was done using STATA 16 software. The quality assessment and publication bias of RCTs were judged using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. For non-RCTs, the assessment was performed using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale21. Quality of evidence was categorized according to GRADE methodology, which differentiates four levels of evidence quality (that is, high, moderate, low or very low) on the basis of the degree of confidence that the effect measured after the analysis of the grouped studies is close to the true effect22 (see Supplementary Information, section B).

The summarized scientific evidence was sent to the expert panel and central review committee for revision and was later presented to the expert panel during two virtual meetings and recommendations were then drafted. The draft recommendations were reviewed and re-drafted by the central review committee and presented to the three patient representatives. The perspectives of these three patients with axSpA were included using focus group methodology, in order to understand their expectations and preferences regarding the topics addressed by the axSpA treatment guideline. The contributions from the patient’s perspective were considered in the formulation of the recommendations (see Supplementary Information, section E). In two additional virtual meetings, the revised recommendations, including the patients’ comments, were presented to the panel of experts who then voted on each recommendation on a 1 to 9 scale, with 1 indicating strong disagreement and 9 indicating strong agreement; agreement was considered a score ≥7. All recommendations required the achievement of a level of agreement of ≥70% at the voting stage. Strong recommendations required a level of agreement of ≥80% at the voting stage. Each recommendation was made considering the risk-to-benefit ratio and the quality of the evidence available for each intervention considered. A recommendation could be either in favour or against the proposed intervention and be qualified as being strong or conditional (that is, weak) (see Supplementary Information, section F).

Regarding data sharing, information about these guidelines will be available via the PANLAR website. Upon request, explanatory tables will be available free of charge to any physician. Materials for patients will be developed and made available on the PANLAR website.

The final manuscript was drafted at the end of the process, reviewed, revised and approved by all panel members before submission to the journal. All authors listed in this manuscript have participated in planning, drafting, reviewing, providing final approval and are accountable for all aspects of the manuscript. Two rheumatologist experts in axSpA acted as external reviewers and made suggestions that were incorporated into the final manuscript. PANLAR plans to update these recommendations on a regular basis, as new data become available and are published in the literature.

Recommendations

The literature search flow chart is presented in the Supplementary Information, section D. The set of treatment recommendations for patients with axSpA is presented in this section. In addition, definitions of terminology on disease concepts is depicted in18,23,24,25 Table 1, and all current recommendations are provided in Table 2. In addition, an algorithm for the pharmacological management of patients diagnosed with axSpA is proposed in Fig. 1.

Patients with active axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) should start treatment with continuous NSAIDs (step 1) and, according to treatment response, continue with on-demand NSAIDs or move to step 2. Step 2 describes the treatment options according to the presence of isolated manifestations and/or contraindications to the use of biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs). After treatment initiation, patients should be re-assessed to determine whether or not treatment should be escalated. Patients whose disease remains active should move to step 3, in which treatment should be switched or cycled according to the type of treatment failure. Patients who achieve remission in step 2 could be considered for treatment optimization, as shown in step 3. *Regular and periodic monitoring with ankylosing spondylitis disease activity score and/or Bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index and using C-reactive protein and/or erythrocyte sedimentation rate; no systematic use of MRI and/or radiography. **Consider gradually reducing the bDMARD dose or extending the interval of administration. IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IL-17i, IL-17 inhibitor; JAK, Janus kinase; JAKi, JAK inhibitor; TNFi, TNF inhibitor; tsDMARD, target synthetic DMARD.

Recommendation 1: Target-based treatment strategy

In patients with active axSpA, a target-based treatment strategy based on clinical criteria is conditionally recommended, supported by a clinimetric tool (Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) and/or Simplified Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (SASDAS))

Despite the failure of the TICOSPA trial to show the benefits of the treat-to-target (T2T) strategy and the challenges of defining the ideal target, the panel of experts conditionally recommended the use of a T2T strategy, on the basis of indirect evidence that lower disease activity is associated with lesser radiographic progression, and on the regular use of T2T in daily clinical practice in many of the PANLAR countries26,27. This recommendation is based on expert opinion only and is not evidence-based. The panel considered that, although remission (defined according to the measures of disease activity suggested in recommendation 13) is the preferred target of the T2T strategy, the fact that most patients with axSpA will achieve only sustained low disease activity during long-term treatment28 should be considered and thus sustained low disease activity might be an alternative target for many patients.

Recommendation 2: Treatment with NSAIDs

In patients with active axSpA, treatment with NSAIDs is strongly recommended as initial pharmacological management. No particular NSAID is recommended as a preferred option. In patients with active axSpA, continuous treatments with NSAIDs instead of on-demand treatment is conditionally recommended, whereas on-demand treatment is strongly recommended over continuous treatment for patients with stable disease

There is ample experience29,30,31,32,33,34,35 that NSAIDs improve axSpA symptoms (defined by pain, stiffness or by the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI)) compared with placebo36. Regarding comparisons between NSAIDs, the direct evidence has shown no significant differences between different NSAIDs30,32,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58. The evidence regarding continuous or on-demand treatment with NSAIDs is inconsistent, as some studies report less radiographic progression with continuous treatment, whereas others do not report significant between-group differences59,60,61,62.

Because of these inconsistencies regarding disease progression, the panel suggests the continuous use of NSAIDs in patients with active axSpA only to control symptoms, but not to attempt to control the progression of structural damage. The panel recommends that NSAID failure should be considered after 1 month of continuous use (at least two NSAIDs for 15 days each), on the basis of findings from trials of NSAIDs and cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) inhibitors indicating that pain and stiffness measures differed from placebo in the first week and the maximum effect was achieved from 2 to 4 weeks30,32. Acknowledging the risk of adverse events with NSAID treatment, the use of selective COX2 inhibitors is recommended, when they are available, in patients at a high risk of serious adverse events, and on-demand use is strongly recommended when the treatment goal is achieved sustainably.

Recommendation 3: Treatment with systemic and local glucocorticoids

In patients with axSpA, the long-term use of systemic glucocorticoids is strongly recommended against. In those with isolated active sacroiliitis despite NSAID treatment, and in those with stable axial disease and active enthesitis or active monoarthritis or oligoarthritis despite treatment with NSAIDs, local administration of glucocorticoids is conditionally recommended

The panel considers that there is scant evidence for the long-term use of systemic glucocorticoids in the treatment of patients with axSpA and that the risks associated with this treatment outweigh the benefits. The recommendation for the use of systemic glucocorticoids was adapted from the ACR–SAA–SPARTAN guideline18.

Two poor-quality RCTs with small sample sizes63,64 and three observational studies65,66,67 showed improvement in pain and some disease activity indices with local injection of glucocorticoids in the sacroiliac join. The panel recommends that this procedure should be performed in experienced specialist centres, and that the use of imaging (ultrasonography or CT), when available, is preferred for the administration of glucocorticoids in active sacroiliitis.

A systematic literature review published in 2021 evaluated the efficacy and safety of intra-articular or local application of glucocorticoids in patients with axSpA68. The review included seven studies, specifically two RCTs involving intra-articular application and five observational studies that assessed local injections for enthesitis, which had low- to very low-quality evidence. These studies showed sustained responses with intra-articular injection, and good responses and improvement in pain after ultrasound-guided administration, in patients with enthesitis and tendinitis. Although there is some evidence that guided glucocorticoid injections might be more efficacious and less painful than blind injections, the panel considers that both blinded and guided injections might be used by trained caregivers66. The panel recommended the avoidance of peritendinous injections of the Achilles, patellar and quadriceps tendons.

Recommendation 4: Treatment with conventional DMARDs

In patients with axSpA with purely axial involvement that is active despite treatment with NSAIDs, treatment with sulfasalazine, methotrexate or leflunomide is strongly recommended against. Sulfasalazine can be a treatment option in patients with active peripheral arthritis

Most of the evidence that evaluated sulfasalazine was published before the development of the current composite clinimetric scales69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76. In general, mild or no improvement is reported in axial symptoms with benefit in peripheral arthritis77,78. Neither methotrexate nor leflunomide showed benefit over placebo for usual axSpA outcomes79,80,81,82,83.

Sulfasalazine, a drug that is widely available in the PANLAR region, can be used in patients with axSpA and active peripheral arthritis.

Recommendation 5: Treatment with biologic DMARDs or JAK inhibitors

In patients with active axSpA with an inadequate response to NSAID treatment, treatment with biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs) (TNF inhibitor or IL-17 inhibitor) is strongly recommended. When bDMARDs are contraindicated or unavailable, treatment with Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors is strongly recommended

There is evidence from RCTs of the efficacy of TNF inhibitors, IL-17 inhibitors and JAK inhibitors in axSpA84,85,86,87,88,89,90. The following bDMARDs are approved for use in most Latin American countries for the treatment of axSpA: adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab, certolizumab pegol, infliximab, secukinumab and ixekizumab, and the JAK inhibitors tofacitinib and upadacitinib.

As no head-to-head trials are available, the panel decided not to prioritize any one class over the other.

The panel considered that there is more evidence for TNF inhibitors and IL-17 inhibitors as there are data not only from RCTs but also from large observational studies and over longer follow-up times than for JAK inhibitors, for which data are mainly from RCTs; thus, the panel recommended initially considering TNF inhibitors and IL-17 inhibitors over JAK inhibitors, and reserve JAK inhibitors for when TNF inhibitor and IL-17 inhibitor therapies are contraindicated or not available.

Use of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib was reported to be associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events, as well as an increased risk of malignancies, compared with TNF inhibitors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis aged ≥50 years and with at least one cardiovascular risk factor91. Although the panel strongly recommends JAK inhibitors when bDMARDs cannot be used, we also conditionally recommend (on the basis of expert opinion) that in patients ≥65 years old with a history of smoking or risk factors for cardiovascular disease or malignancy JAK inhibitors should be used only if no suitable alternatives exist. The treating physician should also consider warnings by some regulatory agencies in the Americas.

In addition, the panel emphasizes that in choosing bDMARDs, factors including availability, accessibility, cost and patient preferences (for example, regarding route of administration) should be taken into account. Specific recommendations related to extra-musculoskeletal manifestations are given in recommendations 9 and 10.

Recommendation 6: Combination therapy

In patients who achieve a stable or inactive disease activity state after treatment with bDMARDs and NSAIDs and/or conventional synthetic DMARD (csDMARDs), discontinuation of NSAIDs and/or csDMARDs is strongly recommended. In patients with axSpA in remission, the use of combination therapy with bDMARDs plus a csDMARD is strongly recommended against

Two RCTs92,93 and two observational studies94,95 that compared combination therapy (bDMARDs plus csDMARDs) with bDMARD monotherapy showed no benefit for combination therapy. Similarly, a post hoc analysis of an RCT, evaluating the efficacy of combination therapy versus monotherapy with different mechanisms of action, found no significant differences.

An analysis of 13 registries in Europe published in 2022 found that co-therapy with csDMARDs and TNF inhibitors in patients with axSpA was associated with higher TNF inhibitor retention and remission rates, although the clinical significance of these findings is doubtful. The authors concluded that 1-year treatment outcomes for TNF inhibitor monotherapy and csDMARD co-therapy were very similar, although certain subgroups of patients (for example, those with peripheral arthritis) might benefit from co-therapy96.

The panel considers that, although the use of combination therapy is common practice in many countries, no benefit is obtained from combining bDMARDs with csDMARDs in axSpA without peripheral involvement. The use of combination therapy can be considered in patients with peripheral involvement, or with other manifestations such as uveitis or IBD. The expert panel also strongly recommends against the use of combination therapy with csDMARDs in patients with an inadequate response to TNF inhibition, as no evidence of the efficacy of combination therapy was found.

The panel considered that in patients in remission following treatment with bDMARDs, there is no need to continue the use of NSAIDs, even though no study has addressed this issue.

Recommendation 7: Biosimilars

In patients with active axSpA and an indication for bDMARDs, biosimilars are also strongly recommended as a therapeutic option

Three clinical trials comparing innovator molecules (infliximab97 and adalimumab98,99) with their biosimilars for the treatment of axSpA showed no significant differences in efficacy, safety or tolerability. In addition, a registry that included 2,334 patients with axSpA100 and compared treatment retention between the innovator and biosimilar versions of infliximab and etanercept reported no differences in drug survival curves.

The panel strongly recommends the use of approved biosimilars as an option in patients with axSpA who need to start treatment with a bDMARD; the use of biosimilars will depend on availability and cost considerations. Recognizing that switching between innovator bDMARDs and their biosimilars, even in patients with stable disease, has been shown to be effective and safe, the expert panel conditionally recommends (on the basis of expert opinion) switching to a biosimilar when this switch will result in considerably reduced (>20%) costs101.

Recommendation 8: Primary and secondary treatment failure

In patients with active axSpA and primary treatment failure with a first bDMARD (TNF inhibitor or IL-17 inhibitor), treatment with a bDMARD with a different mechanism of action (IL-17 inhibitor or TNF inhibitor, respectively) or a JAK inhibitor is strongly recommended. In patients with active axSpA and secondary failure with a first bDMARD (TNF inhibitor or IL-17 inhibitor) or JAK inhibitor, cycling or switching between therapies with any of the three mechanisms of action (TNF inhibition, IL-17 inhibition or JAK inhibition) is strongly recommended

This recommendation is based on expert opinion only, and it is not evidence-based. Although no RCT has been conducted of TNF inhibitor therapies in patients with an insufficient response to TNF inhibition, observational data suggest that a second TNF inhibitor can still be efficacious in those patients, although with a lower level of efficacy than in patients who are naive to TNF inhibition. IL-17 inhibitors and JAK inhibitors have shown efficacy in patients with an inadequate response to treatment with a TNF inhibitor84,102,103,104.

Despite there being no studies that compare responses to switching (that is, a change of mechanism of action) versus cycling (that is, a change of drug but with the same mechanism of action) in the settings of primary failure (no response after initiation of therapy) and secondary failure (loss of response after an initial response), on the basis of common practice among rheumatologists in PANLAR countries the panel strongly recommends switching to a bDMARD with a different mechanism of action or to a JAK inhibitor in patients with primary failure; in patients with secondary failure of a bDMARD, cycling to a bDMARD with the same mechanism of action, or switching to a bDMARD with a different mechanism of action or to a JAK inhibitor, is strongly recommended. In both primary and secondary failure, the panel also recommends investigating other causes of pain that might be due to spinal disorders that are distinct from axSpA.

Recommendation 9: Uveitis

In patients with axSpA and acute uveitis, collaborative management with an ophthalmologist is strongly recommended. In patients with axSpA and recurrent and/or refractory uveitis, treatment with monoclonal antibody TNF inhibitor therapies over other bDMARDs is conditionally recommended

Evidence of the efficacy of bDMARDs in preventing the onset or recurrence of uveitis comes from indirect comparisons of acute anterior uveitis (AAU) flare rates in clinical trials (clustered analyses) or from observational studies. In general, uveitis incidence rates were lower in those treated with adalimumab or infliximab than in those treated with etanercept105,106,107,108,109.

The most recent observational studies report that monoclonal anti-TNF antibodies are more efficacious than etanercept in reducing the recurrence of AAU110.

Analyses from the Swedish Rheumatology Quality Register, with 4,851 treatment initiations, reported that the risk of the first AAU (using adalimumab as a reference) was greater with secukinumab (odds ratio (OR) 2.32; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.16–4.63) and etanercept (OR 1.82; 95% CI 1.13–2.93)), with no differences between golimumab, certolizumab pegol or infliximab111.

The panel recommends that the diagnosis and follow-up of AAU should be performed by an ophthalmologist.

Recommendation 10: Inflammatory bowel disease

In patients with axSpA and IBD, collaborative management with a gastroenterologist is strongly recommended. Avoidance of the use of NSAIDs and IL-17 inhibitors in patients with axSpA and active IBD is strongly recommended. In patients with axSpA and IBD, monoclonal antibody TNF inhibitor therapies are strongly recommended over treatment with other bDMARDs or JAK inhibitors. In patients with axSpA and ulcerative colitis with a contraindication to or lack of access to monoclonal antibody TNF inhibitor therapies, JAK inhibitors are conditionally recommended

This recommendation is based on indirect evidence regarding the risk of flares or new onset of IBD among patients with axSpA during treatment with different drugs, and from the extensive literature on the treatment of IBD in general. There is evidence that NSAIDs might precipitate de novo IBD or exacerbate pre-existing disease, and avoidance of NSAIDs is recommended in the guidelines for the treatment of IBD112. Infliximab, adalimumab and certolizumab are approved for the treatment of Crohn’s disease, and infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab and tofacitinib are approved for the treatment of ulcerative colitis, whereas etanercept is not approved for either condition113,114,115. The strong recommendation of TNF inhibitors over JAK inhibitors is based on the fact that the most frequent form of IBD in patients with axSpA is Crohn’s disease, and at the time of the literature review for this Evidence-Based Guideline tofacitinib was the only JAK inhibitor approved for the treatment of IBD, and only for ulcerative colitis. Upadacitinib has since been approved in some countries for use in adults with moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease who have had an inadequate response or intolerance to one or more TNF inhibitors. Even with this new evidence, the expert panel considers that the strong recommendation of anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies holds.

There is also evidence of a lack of efficacy of IL-17 inhibition therapy in patients with IBD116, so the panel strongly recommend against the use of IL-17 inhibitors in patients with active IBD.

Recommendation 11: Tapering of bDMARDs

In patients with axSpA in sustained remission for at least 12 months and receiving treatment with bDMARDs, tapering (reducing the dose or extending the intervals) of bDMARDs is conditionally recommended. Avoiding abrupt discontinuation of bDMARD treatment is strongly recommended

There is good evidence from RCTs and observational studies that abrupt discontinuation of bDMARDs in patients with axSpA in remission for >6 months is associated with a high proportion of flares, whereas tapering is successful in maintaining disease control117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144.

Although there is no agreement on the definition of sustained remission, the expert panel agreed that, before considering tapering, a patient should be in remission for a minimum period of 12 months (on the basis of expert opinion only).

Recommendation 12: Physical medicine and rehabilitation

In patients with axSpA (during all stages of the disease), combining pharmacological treatment with physical therapy is strongly recommended. Physical therapy and exercise should be managed by experts in physical medicine and rehabilitation. Active physical therapy and supervised exercise is strongly recommended over passive physical therapy and unsupervised exercise. In patients with active axSpA and spinal fusion or advanced spinal osteoporosis, avoiding treatments that involve spinal manipulation is strongly recommended

Clinical trial results favour the performance of any physical therapy compared with none in patients with active axSpA145,146, in adults with nr-axSpA147,148 and in patients with stable axSpA149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159.

There is indirect evidence showing serious adverse events in patients with different diseases, including axSpA, who are subjected to spinal manipulation160,161,162,163,164.

The expert panel underscores the importance of exercise supervision in patients with axSpA. However, the difficulty of providing this health care service in many Latin American countries permits the consideration of unsupervised home-based exercises for patients who have been trained to properly exercise.

Recommendation 13: Measure of disease activity

In patients with axSpA, monitoring at regular intervals, using ASDAS and/or SASDAS, C-reactive protein and/or erythrocyte sedimentation rate as measurements of disease activity, is strongly recommended. Evaluation of bone metabolism, bone mineral density and fracture risk with validated methods is also strongly recommended. The routine use of MRI and/or radiographic studies to follow-up patients with axSpA is strongly recommended against

Monitoring disease activity is crucial in axSpA. By ‘regular intervals’ the panel means monitoring every 3 to 4 months when initiating a new therapy. ASDAS is considered the most appropriate instrument for the assessment of disease activity, because it more closely correlates with radiographic progression and with MRI changes than other commonly used tools such as the BASDAI165. ASDAS also has validated cut-offs values to define disease activity states23.

The panel also considers that the SASDAS, which has been validated as an outcome measurement, could also be used166. As the BASDAI is a less accurate disease activity measure and only reflects the patient perspective, even though many rheumatologists are accustomed to using it, the expert panel considers that the BASDAI should be used for monitoring patients only in exceptional circumstances, when C-reactive protein (CRP) and/or the erythrocyte sedimentation rate are not available.

The value of MRI in the follow-up of patients with axSpA is still unclear; thus, the panel does not recommend its use for monitoring patients, considering issues of accessibility and cost. MRI should be reserved for instances when there are doubts about the origin of the symptoms that might arise during follow-up. Structural damage progression evidenced by radiographs is very slow and does not always correlate with spinal mobility or QoL, and will rarely lead to alteration of treatment; thus, the panel does not recommend the routine use of radiography in the monitoring of patients with axSpA.

Inflammation affects bone quality, microarchitecture, bone remodelling, bone turnover and mineralization, which are risk factors for fragility fractures independently of glucocorticoid use.

A large body of evidence indicates that bone mineral density (BMD) is reduced in patients with axSpA, who are at a high risk of developing vertebral fractures167. axSpA is associated with bone loss (mainly in the vertebrae) and osteoporosis, and the risk of vertebral fracture is increased seven-fold in patients with axSpA than in the general population168.

The expert panel recommends that measurement of BMD at the spine and hip by use of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) should be performed after axSpA diagnosis. BMD measurement by DXA should then be performed annually in those patients with low BMD, osteoporosis or fragility fractures or who are being treated with drugs related to reduced BMD or with drugs for osteoporosis169.

Discussion

The current Evidence-Based Guideline document presents recommendations provided by PANLAR regarding the pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment of adults diagnosed with axSpA (radiographic and non-radiographic disease). The recommendations provide guidance on the management of this condition in the Americas, where the characteristics of the population and health care systems require unique consideration to bring evidence into daily clinical practice. Within this objective, the generation of the recommendations was performed using a comprehensive review of the scientific literature considering interventions in axSpA and considering the decision-making process for their implementation, including strategies to achieve therapeutic objectives and the optimization of bDMARDs.

The PANLAR guidance for the management of axSpA has been developed as 13 recommendations covering r-axSpA and nr-axSpA and both pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment. First-line therapy for most patients with axSpA in these recommendations remains NSAIDs, without any preference for one particular drug over others, but with only 1 month to assess response. After failure of NSAIDs, bDMARDs, including TNF inhibitors and IL-17 inhibitors, are recommended without prioritization for one class of drugs over the other, because they have similar efficacy; this affirmation comes from indirect evidence, as at the time of literature review for these recommendations no head-to-head trials had been published. The results from the SURPASS trial have since been presented and show similar results between an IL-17 inhibitor and a TNF inhibitor in r-axSpA170. In these PANLAR recommendations, JAK inhibitors have been reserved for those cases in which bDMARDs are contraindicated, but also in cases in which access to bDMARDs is limited, a situation that often occurs in Latin America.

In 2019, the ACR–SAA–SPARTAN recommendations were published18 and in 2023 updated recommendations from the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) and EULAR were also published12. Despite the fact that the ACR–SAA–SPARTAN recommendations were used as the source guideline for these PANLAR recommendations, there are several differences between them. In the ACR–SAA–SPARTAN guidelines, TNF inhibitor therapies are recommended over IL-17 inhibitors as second-line therapy after NSAID failure, whereas in the PANLAR guidelines there is no prioritization of one over the other. Much of the evidence about the long-term efficacy and safety of anti-IL-17 drugs was published during the period between the two sets of recommendations, enabling PANLAR to recommend these bDMARDs equally to TNF inhibitors. Also, the ACR–SAA–SPARTAN guidelines recommend against tapering bDMARDs in patients with stable disease, whereas the PANLAR recommendations encourage optimization of therapy in patients in a state of sustained remission (at least 12 months). The ACR–SAA–SPARTAN guidelines strongly recommend continuing with the originator bDMARD over switching to a biosimilar in patients with stable axSpA; the PANLAR guidelines, in view of the proven economic benefits and safety of approved biosimilars, recommends their use and switching from the innovator drug to its biosimilar in patients with stable disease. The ACR–SAA–SPARTAN guidelines conditionally recommend against the use of a T2T strategy, whereas the PANLAR recommendations adhere to this concept. Despite the failure of the TICOSPA trial26, the experts from PANLAR believe that the frequent assessment of disease activity using recommended activity scores and the adjustment of treatment when the outcome is not achieved (a T2T strategy) should be the applied strategy. Finally, whereas the ACR–SAA–SPARTAN guidelines only mentioned osteoporosis screening at baseline, the PANLAR guidelines also included clear recommendations with regard to its monitoring. The ASAS–EULAR guidelines12 did not mention osteoporosis at all.

The PANLAR Evidence-Based Guideline has many similarities with the ASAS–EULAR guidelines12 (such as preferred choices when switching, tapering treatment and the use of a T2T strategy), probably because they were formulated during the same period and are more recent than the ACR–SAA–SPARTAN guidelines. Certainly, the general framework for treatment modalities is complementary and aligned, supporting the management of these patients worldwide. Additionally, both guidelines are focused on treating axSpA as a single disease, with a comprehensive treatment strategy, emphasizing both non-pharmacological interventions and including novel mechanisms of action, such as JAK inhibitors. However, there are also some differences. Whereas the PANLAR Evidence-Based Guideline differentiates the recommendation after failure of the first bDMARD according to primary or secondary failure, there is no such difference in the recommendations in the ASAS–EULAR guidelines. The ASAS–EULAR document recommends the use of ASDAS to measure disease activity, whereas the PANLAR experts recommend the use of either ASDAS or SASDAS, or even BASDAI, as CRP is not always readily available in PANLAR countries.

Further efforts should be made to implement this PANLAR Evidence-Based Guideline, including its dissemination among national scientific societies and meetings, as well as educational activities for physicians and other health professionals. Additional implementation strategies, such as an evaluation of adherence to the recommendations and monitoring of indicators, should be developed locally.

The analysis of the impact of the recommendations on the use of resources was not addressed directly, given the need for adjustment to the economic and health system situation of each PANLAR country. Therefore, the cost-effectiveness of the interventions evaluated will require local economic studies. However, the economic impact was considered during the development and generation of this Evidence-Based Guideline, in order to provide benefit to the patient with the use of highly effective and safe therapies in balance with their rationale. In this regard, several issues concerning lacking or scarce data were discussed as potential areas for the research agenda in the Americas, especially in Latin America.

Among the limitations of this Evidence-Based Guideline, we acknowledge that the certainty of the evidence was not as high as desired for several of the recommendations and is probably biased by the scarcity of RCTs. Therefore, these recommendations should be updated as new information and additional therapeutic options become available. In many cases, strong recommendations were adopted even with a low or moderate level of evidence. In all such cases, the experts were confident that the desirable effects of adherence to those recommendations outweigh the undesirable effects. In all cases, strong recommendations had levels of agreement ≥80%. Another limitation is that a considerable amount of time has elapsed since the end of SLR and the publication of this Evidence-Based Guideline. However, only one drug has been approved for the treatment of axSpA during that time (upadacitinib), which, although not specifically included in the recommendations, is somehow included within the class of JAK inhibitors.

Although education and lifestyle changes are important in the management of axSpA, we did not include PICO questions and literature searches on those topics, so no recommendations were performed related to them. Another limitation is that we have not included recommendations on the treatment of psoriasis, a frequent extra-musculoskeletal manifestation in axSpA. As PANLAR is preparing separate guidelines on the management of psoriatic arthritis, this topic will be addressed there. Finally, some recommendations are based only on expert opinion, such as the conditional recommendation of using the T2T strategy. The panel of experts strongly feels that the principles of frequent assessment using a validated tool and the escalation of treatment when the target is not achieved (in agreement with the patient) should be encouraged in Latin America. To try to avoid overtreatment in some patients, the panel also recommends considering other reasons for pain when an effective treatment fails.

This Evidence-Based Guideline should be considered by the health systems of different countries and implemented by rheumatologists and other professionals, with the aim of reducing variability and improving the treatment of axSpA, especially in Latin America. Additionally, these recommendations are intended for the treatment approach for a typical patient and cannot anticipate all possible clinical scenarios; therefore, their application must be individualized.

Conclusions

These recommendations represent the first PANLAR Evidence-Based Guideline for the management of axSpA and are expected to be useful for all health professionals involved in the management of patients with axSpA, including rheumatologists, patients, payers and decision-makers in health systems. It is our hope that the current recommendations will contribute to standardizing and optimizing the treatment of axSpA through higher quality management of the condition.

References

Navarro-Compán, V., Sepriano, A., El-Zorkany, B. & van der Heijde, D. Axial spondyloarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 80, 1511–1521 (2021).

Rudwaleit, M. et al. The development of the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 68, 777–783 (2009).

Bautista-Molano, W. et al. Analysis and performance of various classification criteria sets in a Colombian cohort of patients with spondyloarthritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 35, 1759–1767 (2016).

López-Medina, C. et al. Prevalence and distribution of peripheral musculoskeletal manifestations in spondyloarthritis including psoriatic arthritis: results of the worldwide, cross-sectional ASAS-PerSpA study. RMD Open. 7, e001450 (2021).

Stolwijk, C., van Onna, M., Boonen, A. & van Tubergen, A. Global prevalence of spondyloarthritis: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Arthritis Care. Res. 68, 1320–1331 (2016).

Citera, G. et al. Prevalence, demographics, and clinical characteristics of Latin American patients with spondyloarthritis. Adv. Rheumatol. 61, 2 (2021).

Boonen, A. et al. The burden of non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 44, 556–562 (2015).

Garrido-Cumbrera, M. et al. EMAS working group. Impact of axial spondyloarthritis on mental health in Europe: results from the EMAS study. RMD Open. 7, e001769 (2021).

Moltó, A. et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and evaluation of their screening in spondyloarthritis: results of the international cross-sectional ASAS-COMOSPA study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75, 1016–1023 (2016).

Bautista-Molano, W. et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and risk factors for comorbidities in patients with spondyloarthritis in Latin America: a comparative study with the general population and data from the ASAS-COMOSPA study. J. Rheumatol. 45, 206–212 (2018).

Zhao, S. S. et al. Comorbidity burden in axial spondyloarthritis: a cluster analysis. Rheumatology 58, 1746–1754 (2019).

Ramiro, S. et al. ASAS-EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis: 2022 update. Ann. Rheum. 82, 19–34 (2023).

Reyes-Cordero, G. et al. Recommendations of the Mexican College of Rheumatology for the management of spondyloarthritis. Reumatol. Clin. 17, 37–45 (2021).

Resende, G. G. et al. The Brazilian Society of Rheumatology guidelines for axial spondyloarthritis - 2019. Adv. Rheumatol. 21, 60 (2020). 19.

Rohekar, S. et al. 2014 update of the Canadian Rheumatology Association/Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada Treatment Recommendations for the management of spondyloarthritis. part II: specific management recommendations. J. Rheumatol. 42, 665–681 (2015).

Bautista-Molano, W. et al. 2021 clinical practice guideline for the early detection, diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Colombian Association of Rheumatology. Reumatol. Clin. 18, 191–199 (2022).

Flodgren, G., O’Brien, M. A., Parmelli, E. & Grimshaw, J. M. Local opinion leaders: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 24, CD000125 (2019). 6.

Ward, M. M. et al. 2019 Update of the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis. research and treatment network recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Care. Res. 71, 1285–1299 (2019).

Schünemann, H. J. et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks for adoption, adaptation, and de novo development of trustworthy recommendations: GRADE-ADOLOPMENT. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 81, 101–110 (2017).

Brouwers, M. C., Kerkvliet, K. & Spithoff, K., AGREE Next Steps Consortium. The AGREE reporting checklist: a tool to improve reporting of clinical practice guidelines. Br. Med. J. 352, i1152 (2016).

Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 25, 603–605 (2010).

Guyatt, G. H. et al. Going from evidence to recommendations. Br. Med. J. 336, 1049–1051 (2008).

Machado, P. et al. Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society. Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS): defining cut-off values for disease activity states and improvement scores. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70, 47–53 (2011).

Jabs, D. A., Nussenblatt, R. B. & Rosenbaum, J. T., Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the first international workshop. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 140, 509–516 (2005).

Kalden, J. & Schulze-Koops, H. Immunogenicity and loss of response to TNF inhibitors: implications for rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 13, 707–718 (2017).

Molto, A. et al. Efficacy of a tight-control and treat-to-target strategy in axial spondyloarthritis: results of the open-label, pragmatic, cluster-randomised TICOSPA trial. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 80, 1436–1444 (2021).

US National Library of Medicine. A study treating participants with early axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) taking an intense treatment approach versus routine treatment (STRIKE). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02897115 (2019).

Sieper, J. & Poddubnyy, D. What is the optimal target for a T2T approach in axial spondyloarthritis? Ann. Rheum. Dis. 80, 1367–1369 (2021).

van Bentum, R. E. & van der Horst-Bruinsma, I. E. Axial spondyloarthritis in the era of precision medicine. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 46, 367–378 (2020).

Barkhuizen, A. et al. Celecoxib is efficacious and well tolerated in treating signs and symptoms of ankylosing spondylitis. J. Rheumatol. 33, 1805–1812 (2006).

Benhamou, M., Gossec, L. & Dougados, M. Clinical relevance of C-reactive protein in ankylosing spondylitis and evaluation of the NSAIDs/coxibs’ treatment effect on C-reactive protein. Rheumatology 49, 536–541 (2010).

Dougados, M. et al. Efficacy of celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase 2-specific inhibitor, in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a six-week controlled study with comparison against placebo and against a conventional nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug. Arthritis Rheum. 44, 180–185 (2001).

Dougados, M. et al. Ankylosing spondylitis: what is the optimum duration of a clinical study? A one year versus a 6 weeks non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug trial. Rheumatology 38, 235–244 (1999).

Van Der Heijde, D. et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of etoricoxib in ankylosing spondylitis: results of a fifty-two-week, randomized, controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. 52, 1205–1215 (2005).

Fattahi, M. J. et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of β-D-mannuronic acid in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a 12-week randomized, placebo-controlled, phase I/II clinical trial. Int. Immunopharmacol. 54, 112–117 (2018).

Fan, M. et al. Indirect comparison of NSAIDs for ankylosing spondylitis: network meta-analysis of randomized, double-blinded, controlled trials. Exp. Ther. Med. 19, 3031–3041 (2020).

Sieper, J. et al. Comparison of two different dosages of celecoxib with diclofenac for the treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis: results of a 12-week randomised, double-blind, controlled study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 67, 323–329 (2008).

Mena, H. R. & Good, A. E. Management of ankylosing spondylitis with flurbiprofen or indomethacin. South. Med. J. 70, 945–947 (1977).

Calin, A. & Britton, M. Sulindac in ankylosing spondylitis: double-blind evaluation of sulindac and indomethacin. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 242, 1885–1886 (1979).

Sydnes, O. A. Comparison of piroxicam with indomethacin in ankylosing spondylitis: a double-blind crossover trial. Br. J. Clin. Pract. 35, 40–44 (1981).

Palferman, T. G. & Webley, M. A comparative study of nabumetone and indomethacin in ankylosing spondylitis. Eur. J. Rheumatol. Inflamm. 11, 23–29 (1991).

Calabro, J. J. Efficacy of diclofenac in ankylosing spondylitis. Am. J. Med. 80, 58–63 (1986).

Tannenbaum, H., DeCoteau, W. E. & Esdaile, J. M. A double blind multicenter trial comparing piroxicam and indomethacin in ankylosing spondylitis with long-term follow-up. Curr. Ther. Res. Clin. Exp. 36, 426–435 (1984).

Ebner, W., Poal Ballarin, J. M. & Boussina, I. Meclofenamate sodium in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Report of a European double-blind controlled multicenter study. Arzneimittelforschung 33, 660–663 (1983).

Burry, H. C. & Siebers, R. A comparison of flurbiprofen with naproxen in ankylosing spondylitis. N. Z. Med. J. 92, 309–311 (1980).

Franssen, M. J. A. M., Gribnau, F. W. J. & Van De Putte, L. B. A. A comparison of diflunisal and phenylbutazone in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Clin. Rheumatol. 5, 210–220 (1986).

Wordsworth, B. P., Ebringer, R. W., Coggins, E. & Smith, S. A double-blind cross-over trial of fenoprofen and phenylbutazone in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology 19, 260–263 (1980).

Gibson, T. & Laurent, R. Sulindac and indomethacin in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a double-blind cross-over study. Rheumatology 19, 189–192 (1980).

Shipley, M., Berry, H. & Bloom, B. A double-blind cross-over trial of indomethacin, fenoprofen and placebo in ankylosing spondylitis, with comments on patient assessment. Rheumatology 19, 122–125 (1980).

Sturrock, R. D. & Hart, F. D. Double blind crossover comparison of indomethacin, flurbiprofen, and placebo in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 33, 129–131 (1974).

Mena, H. R. & Willkens, R. F. Treatment of ankylosing spondylitis with flurbiprofen or phenylbutazone. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 11, 263–266 (1977).

Ansell, B. M. et al. A comparative study of Butacote and Naprosyn in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 37, 436–439 (1978).

Bacon, P. A. An overview of the efficacy of etodolac in arthritic disorders. Eur. J. Rheumatol. Inflamm. 10, 22–34 (1990).

Wasner, C. et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents in rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 246, 2168–2172 (1981).

Balazcs, E. et al. A randomized, clinical trial to assess the relative efficacy and tolerability of two doses of etoricoxib versus naproxen in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 17, 426 (2016).

Huang, F. et al. Efficacy and safety of celecoxib in Chinese patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a 6-week randomized, double-blinded study with 6-week open-label extension treatment. Curr. Ther. Res. Clin. Exp. 76, 126–133 (2014).

Walker, C., Essex, M. N., Li, C. & Park, P. W. Celecoxib versus diclofenac for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: 12-week randomized study in Norwegian patients. J. Int. Med. Res. 44, 483–495 (2016).

Van Gerwen, F., Van Der Korst, J. K. & Gribnau, F. W. J. Double blind trial of naproxen and phenylbutazone in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 37, 85–88 (1978).

Wanders, A. et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs reduce radiographic progression in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 52, 1756–1765 (2005).

Kroon, F. et al. Continuous NSAID use reverts the effects of inflammation on radiographic progression in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 71, 1623–1629 (2012).

Poddubnyy, D. et al. Effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on radiographic spinal progression in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: results from the German spondyloarthritis inception cohort. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 71, 1616–1622 (2012).

Sieper, J. et al. Effect of continuous versus on-demand treatment of ankylosing spondylitis with diclofenac over 2 years on radiographic progression of the spine: results from a randomised multicentre trial (ENRADAS). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75, 1438–1443 (2016).

Maugars, Y., Mathis, C., Berthelot, J. M., Charlier, C. & Prost, A. Assessment of the efficacy of sacroiliac corticosteroid injections in spondylarthropathies: a double-blind study. Br. J. Rheumatol. 35, 767–770 (1996).

Luukkainen, R. et al. Periarticular corticosteroid treatment of the sacroiliac joint in patients with seronegative spondylarthropathy. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 17, 88–90 (1999).

Günaydin, I., Pereira, P. L., Fritz, J., König, C. & Kötter, I. Magnetic resonance imaging guided corticosteroid injection of sacroiliac joints in patients with spondylarthropathy. Are multiple injections more beneficial? Rheumatol. Int. 26, 396–400 (2006).

Migliore, A. et al. A new technical contribution for ultrasound-guided injections of sacro-iliac joints. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 14, 465–469 (2010).

Nam, B. et al. Efficacy and safety of intra-articular sacroiliac glucocorticoid injections in ankylosing spondylitis. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 28, e26–e32 (2022).

Dhir, V., Mishra, D. & Samanta, J. Glucocorticoids in spondyloarthritis — systematic review and real-world analysis. Rheumatology 60, 4463–4475 (2021).

Nissilä, M. et al. Sulfasalazine in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. A twenty-six-week, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 31, 1111–1116 (1988).

Taylor, H. G., Beswick, E. J. & Dawes, P. T. Sulphasalazine in ankylosing spondylitis. A radiological, clinical and laboratory assessment. Clin. Rheumatol. 10, 43–48 (1991).

Dougados, M., Boumier, P. & Amor, B. Sulphasalazine in ankylosing spondylitis: a double blind controlled study in 60 patients. Br. Med. J. 293, 911–914 (1986).

Davis, M. J., Dawes, P. T., Beswick, E., Lewin, I. V. & Stanworth, D. R. Sulphasalazine therapy in ankylosing spondylitis: its effect on disease activity, immunoglobulin A and the complex immunoglobulin a-alpha-1-antitrypsin. Rheumatology 28, 410–413 (1989).

Corkill, M. M., Jobanputra, P., Gibson, T. & Macfarlane, D. A controlled trial of sulphasalazine treatment of chronic ankylosing spondylitis: failure to demonstrate a clinical effect. Rheumatology 29, 41–45 (1990).

Kirwan, J., Edwards, A., Huitfeldt, B., Thompson, P. & Currey, H. The course of established ankylosing spondylitis and the effects of sulphasalazine over 3 years. Rheumatology 32, 729–733 (1993).

Clegg, D. O. et al. Comparison of sulfasalazine and placebo in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 39, 1911–1912 (1996).

Feltelius, N. & Hallgren, R. Sulphasalazine in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann. Rheum. 45, 396–399 (1986).

Khanna Sharma, S., Kadiyala, V., Naidu, G. & Dhir, V. A randomized controlled trial to study the efficacy of sulfasalazine for axial disease in ankylosing spondylitis. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 21, 308 (2018).

Venkatesh, S., Vishad, V., Viswanath, V., Deepak, T. & Mehtab, A. A prospective double blind placebo controlled trial of combination disease modifying antirheumatic drugs vs monotherapy (sulfasalazine) in patients with inflammatory low backache in ankylosing spondylitis and undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy. J. Arthritis S1 1041722167-7921S1-001 (2015).

Roychowdhury, B. et al. Is methotrexate effective in ankylosing spondylitis? Rheumatology 41, 1330–1332 (2002).

Altan, L. et al. Clinical investigation of methotrexate in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 30, 255–259 (2001).

Gonzalez-Lopez, L., Garcia-Gonzalez, A., Vazquez-Del-Mercado, M., Muñoz-Valle, J. F. & Gamez-Nava, J. I. Efficacy of methotrexate in ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial. J. Rheumatol. 31, 1568–1574 (2004).

Haibel, H. et al. No efficacy of subcutaneous methotrexate in active ankylosing spondylitis: a 16-week open-label trial. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 66, 419–421 (2007).

Van Denderen, J. C. et al. Double blind, randomised, placebo controlled study of leflunomide in the treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 64, 1761–1764 (2005).

Dougados, M. & Wei, J. C. et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab through 52 weeks in two phase 3, randomised, controlled clinical trials in patients with active radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (COAST-V and COAST-W). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 79, 176–185 (2020).

Kiltz, U. & Wei, J. C. et al. Ixekizumab improves functioning and health in the treatment of radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: week 52 results from 2 pivotal studies. J. Rheumatol. 48, 188–197 (2021).

Wu, Y. et al. Model-based meta-analysis in ankylosing spondylitis: a quantitative comparison of biologics and small targeted molecules. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 105, 1244–1255 (2019).

Van Der Heijde, D. et al. Tofacitinib in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a phase II, 16-week, randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76, 1340–1347 (2017).

Deodhar, A. et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 80, 1004–1013 (2021).

van der Heijde, D. S. I. et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (SELECT-AXIS 1): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet 394, 2108–2117 (2019).

van der Heijde, D. B. X. et al. Efficacy and safety of filgotinib, a selective Janus kinase 1 inhibitor, in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (TORTUGA): results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 392, 2378–2387 (2018).

Ytterberg, S. R. et al. ORAL surveillance investigators. cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 316–326 (2022).

Mulleman, D. et al. Infliximab in ankylosing spondylitis: alone or in combination with methotrexate? A pharmacokinetic comparative study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 13, R82 (2011).

Li, E. K. et al. Short-term efficacy of combination methotrexate and infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a clinical and magnetic resonance imaging correlation. Rheumatology 47, 1358–1363 (2008).

Nissen, M. J. et al. The effect of comedication with a conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug on drug retention and clinical effectiveness of anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 68, 2141–2150 (2016).

Pérez-Guijo, V. C. et al. Increased efficacy of infliximab associated with methotrexate in ankylosing spondylitis. Joint Bone Spine 74, 254–258 (2007).

Nissen, M. et al. The impact of a csDMARD in combination with a TNF inhibitor on drug retention and clinical remission in axial spondyloarthritis. Rheumatology 61, 4741–4751 (2022).

Park, W. et al. Comparable long-term efficacy, as assessed by patient-reported outcomes, safety and pharmacokinetics, of CT-P13 and reference infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: 54-week results from the randomized, parallel-group PLANETAS study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 18, 25 (2016).

Xu, H. & Zhijun, L. et al. IBI303, a biosimilar to adalimumab, for the treatment of patients with ankylosing spondylitis in China: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 equivalence trial. Lancet Rheumatol. 1, e35 (2019).

Su, J. & Li, M. et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of adalimumab (Humira) and the adalimumab biosimilar candidate (HS016) in Chinese patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel, phase III clinical trial. BioDrugs 34, 381–393 (2020).

Lindström, U. et al. Treatment retention of infliximab and etanercept originators versus their corresponding biosimilars: Nordic collaborative observational study of 2334 biologics naïve patients with spondyloarthritis. RMD Open 5, e001079 (2019).

Kowalski, S. C. et al. PANLAR consensus statement on biosimilars. Clin. Rheumatol. 38, 1485–1496 (2019).

Deodhar, A. et al. Upadacitinib for the treatment of active non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (SELECT-AXIS 2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 400, 369–379 (2022).

McInnes, I. B. et al. FUTURE 2 Study Group. Secukinumab provides rapid and sustained pain relief in psoriatic arthritis over 2 years: results from the FUTURE 2 study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 20, 113 (2018).

Kavanaugh, A. et al. Efficacy of subcutaneous secukinumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis stratified by prior tumor necrosis factor inhibitor use: results from the randomized placebo-controlled FUTURE 2 study. J. Rheumatol. 43, 1713–1717 (2016).

Guignard, S. et al. Efficacy of tumour necrosis factor blockers in reducing uveitis flares in patients with spondylarthropathy: a retrospective study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 65, 1631–1634 (2006).

Braun, J., Baraliakos, X., Listing, J. & Sieper, J. Decreased incidence of anterior uveitis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with the anti-tumor necrosis factor agents infliximab and etanercept. Arthritis Rheum. 52, 2447–2451 (2005).

Cobo-Ibáñez, T., del Carmen Ordóñez, M., Muñoz-Fernández, S., Madero-Prado, R. & Martín-Mola, E. Do TNF-blockers reduce or induce uveitis? Rheumatology 47, 731–732 (2008).

Fouache, D. et al. Paradoxical adverse events of anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy for spondyloarthropathies: a retrospective study. Rheumatology 48, 761–764 (2009).

Rudwaleit, M. et al. Adalimumab effectively reduces the rate of anterior uveitis flares in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: results of a prospective open-label study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 68, 696–701 (2009).

Lee, S., Park, Y. J. & Lee, J. Y. The effect of tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors on uveitis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J. Korean Med. Sci. 34, e278 (2019).

Lindström, U. et al. Anterior uveitis in patients with spondyloarthritis treated with secukinumab or tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in routine care: does the choice of biological therapy matter? Ann. Rheum. Dis. 80, 1445–1452 (2021).

Lamb, C. A. et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 68, s1–s106 (2019).

Kornbluth, A. & Sachar, D. B. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults: American College of Gastroenterology practice parameters committee. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 105, 501–523 (2010).

Lichtenstein, G. R. et al. ACG clinical guideline: management of Crohn’s disease in adults. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 113, 481–517 (2018).

Sandborn et al. Tofacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 376, 1723–1736 (2017).

Hueber et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibody, for moderate to severe Crohn’s disease: unexpected results of a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Gut 61, 1693–1700 (2012).

Chen, X., Zhang, T., Wang, W. & Xue, J. Analysis of relapse rates and risk factors of tapering or stopping pharmacologic therapies in axial spondyloarthritis patients with sustained remission. Clin. Rheumatol. 37, 1625–1632 (2018).

Li, J. et al. Dose reduction of recombinant human tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (etanercept) can be effective in ankylosing spondylitis patients with synovitis of the hip in a Chinese population. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 29, 510–515 (2016).

Cantini, F., Niccoli, L., Cassarà, E., Kaloudi, O. & Nannini, C. Duration of remission after halving of the etanercept dose in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized, prospective, long-term, follow-up study. Biol. Targets Ther. 7, 1–6 (2013).

Yates, M. et al. Is etanercept 25 mg once weekly as effective as 50 mg at maintaining response in patients with ankylosing spondylitis? A randomized control trial. J. Rheumatol. 42, 1175–1185 (2015).

Lian, F. et al. Efficiency of dose reduction strategy of etanercept in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 36, 884–890 (2018).

Lawson, D. O. et al. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitor dose reduction for axial spondyloarthritis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Care. Res. 73, 861–872 (2021).

Arends, S. et al. Patient-tailored dose reduction of TNF-α blocking agents in ankylosing spondylitis patients with stable low disease activity in daily clinical practice. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 33, 174–180 (2015).

Lee, S.-H., Lee, Y.-A., Hong, S.-J. & Yang, H.-I. Etanercept 25 mg/week is effective enough to maintain remission for ankylosing spondylitis among Korean patients. Clin. Rheumatol. 27, 179–181 (2008).

Almirall, M. et al. Drug levels, immunogenicity and assessment of active sacroiliitis in patients with axial spondyloarthritis under biologic tapering strategy. Rheumatol. Int. 36, 575–578 (2016).

De Stefano, R., Frati, E., De Quattro, D., Menza, L. & Manganelli, S. Low doses of etanercept can be effective to maintain remission in ankylosing spondylitis patients. Clin. Rheumatol. 33, 707–711 (2014).

Plasencia, C. et al. Comparing tapering strategy to standard dosing regimen of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in patients with spondyloarthritis in low disease activity. J. Rheumatol. 42, 1638–1646 (2015).

Závada, J. et al. A tailored approach to reduce dose of anti-TNF drugs may be equally effective, but substantially less costly than standard dosing in patients with ankylosing spondylitis over 1 year: a propensity score-matched cohort study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75, 96–102 (2016).

Navarro-Compán, V. et al. Low doses of etanercept can be effective in ankylosing spondylitis patients who achieve remission of the disease. Clin. Rheumatol. 30, 993–996 (2011).

Lee, J. et al. Extended dosing of etanercept 25 mg can be effective in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a retrospective analysis. Clin. Rheumatol. 29, 1149–1154 (2010).

Paccou, J., Baclé-Boutry, M. A., Solau-Gervais, E., Bele-Philippe, P. & Flipo, R. M. Dosage adjustment of anti-tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor in ankylosing spondylitis is effective in maintaining remission in clinical practice. J. Rheumatol. 39, 1418–1423 (2012).

Fong, W. et al. The effectiveness of a real life dose reduction strategy for tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology 55, 1837–1842 (2016).

Park, J. W. et al. Impact of dose tapering of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor on radiographic progression in ankylosing spondylitis. PLoS One 11, e0168958 (2016).

Mörck, B., Pullerits, R., Geijer, M., Bremell, T. & Forsblad-d’Elia, H. Infliximab dose reduction sustains the clinical treatment effect in active HLAB27 positive ankylosing spondylitis: a two-year pilot study. Mediators Inflamm. 2013, 289845 (2013).

Chen, M. H. et al. Health-related quality of life outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis after tapering biologic treatment. Clin. Rheumatol. 37, 429–438 (2018).

Landewé, R. et al. Efficacy and safety of continuing versus withdrawing adalimumab therapy in maintaining remission in patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (ABILITY-3): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind study. Lancet 392, 134–144 (2018).

Moreno, M. et al. Withdrawal of infliximab therapy in ankylosing spondylitis in persistent clinical remission, results from the REMINEA study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 21, 88 (2019).

Baraliakos, X. et al. Clinical response to discontinuation of anti-TNF therapy in patients with ankylosing spondylitis after 3 years of continuous treatment with infliximab. Arthritis Res. Ther. 7, R439–R444 (2005).

Deng, X., Zhang, J., Zhang, J. & Huang, F. Thalidomide reduces recurrence of ankylosing spondylitis in patients following discontinuation of etanercept. Rheumatol. Int. 33, 1409–1413 (2013).

Breban, M. et al. Efficacy of infliximab in refractory ankylosing spondylitis: results of a six-month open-label study. Rheumatology 41, 1280–1285 (2002).

Heldmann, F. et al. The European Ankylosing Spondylitis Infliximab Cohort (EASIC): a European multicentre study of long-term outcomes in patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with infliximab. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 29, 672–680 (2011).

Zhao, M. et al. Possible predictors for relapse from etanercept discontinuation in ankylosing spondylitis patients in remission: a three years’ following-up study. Clin. Rheumatol. 37, 87–92 (2018).

Sebastian, A. et al. Disease activity in axial spondyloarthritis after discontinuation of TNF inhibitors therapy. Reumatologia 55, 87–92 (2017).

Brandt, J. et al. Six-month results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of etanercept treatment in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 48, 1667–1675 (2003).

Kjeken, I. et al. A three-week multidisciplinary in-patient rehabilitation programme had positive long-term effects in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: randomized controlled trial. J. Rehabil. Med. 45, 260–267 (2013).

Bulstrode, S. J., Barefoot, J., Harrison, R. A. & Clarke, A. K. The role of passive stretching in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology 26, 40–42 (1987).

Cozzi, F. et al. Mud-bath treatment in spondylitis associated with inflammatory bowel disease — a pilot randomised clinical trial. Joint Bone Spine 74, 436–439 (2007).

Viitanen, J. V. & Heikkilä, S. Functional changes in patients with spondylarthropathy. A controlled trial of the effects of short-term rehabilitation and 3-year follow-up. Rheumatol. Int. 20, 211–214 (2001).

Altan, L., Korkmaz, N., Dizdar, M. & Yurtkuran, M. Effect of Pilates training on people with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol. Int. 32, 2093–2099 (2012).

Durmus, D., Alayli, G., Cil, E. & Canturk, F. Effects of a home-based exercise program on quality of life, fatigue, and depression in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol. Int. 29, 673–677 (2009).

Durmuş, D. et al. Effects of two exercise interventions on pulmonary functions in the patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Joint Bone Spine 76, 150–155 (2009).

Rodríguez-Lozano, C. et al. Outcome of an education and home-based exercise programme for patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a nationwide randomised study. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 31, 739–748 (2013).

Kraag, G., Stokes, B., Groh, J., Helewa, A. & Goldsmith, C. The effects of comprehensive home physiotherapy and supervision on patients with ankylosing spondylitis - a randomized controlled trial. J. Rheumatol. 17, 261–263 (1990).

Gemignani, G., Olivieri, I., Ruju, G. & Pasero, G. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in ankylosing spondylitis: a double-blind study. Arthritis Rheum. 34, 788–789 (1991).

Ince, G., Sarpel, T., Durgun, B. & Erdogan, S. Effects of a multimodal exercise program for people with ankylosing spondylitis. Phys. Ther. 86, 924–935 (2006).

Niedermann, K. et al. Effect of cardiovascular training on fitness and perceived disease activity in people with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Care Res. 65, 1844–1852 (2013).

Widberg, K., Hossein, K. & Hafström, I. Self- and manual mobilization improves spine mobility in men with ankylosing spondylitis — a randomized study. Clin. Rehabil. 23, 599–608 (2009).

Masiero, S. et al. Rehabilitation treatment in patients with ankylosing spondylitis stabilized with tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy. A randomized controlled trial. J. Rheumatol. 38, 1335–1342 (2011).

Masiero, S. et al. Supervised training and home-based rehabilitation in patients with stabilized ankylosing spondylitis on TNF inhibitor treatment: a controlled clinical trial with a 12-month follow-up. Clin. Rehabil. 28, 562–572 (2014).

Ernst, E. Adverse effects of spinal manipulation: a systematic review. J. R. Soc. Med. 100, 330–338 (2007).

Hebert, J. J., Stomski, N. J., French, S. D. & Rubinstein, S. M. Serious adverse events and spinal manipulative therapy of the low back region: a systematic review of cases. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther. 38, 677–691 (2015).

Carnes, D., Mars, T. S., Mullinger, B., Froud, R. & Underwood, M. Adverse events and manual therapy: a systematic review. Man. Ther. 15, 355–363 (2010).

Rinsky, L. A., Reynolds, G. G., Jameson, R. M. & Hamilton, R. D. A cervical spinal cord injury following chiropractic manipulation. Paraplegia 13, 223–227 (1976).

Liao, C. C. & Chen, L. R. Anterior and posterior fixation of a cervical fracture induced by chiropractic spinal manipulation in ankylosing spondylitis: a case report. J. Trauma 63, E90–E94 (2007).

Navarro-Compan, V. et al. The ASAS-OMERACT core domain set for axial spondyloarthritis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 51, 1342–1349 (2021).

Schneeberger E. E. et al. Simplified Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (SASDAS) versus ASDAS: a post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. J. Rheumatol. 49, 1100–1108 (2022).

Vosse, D. et al. Ankylosing spondylitis and the risk of fracture: results from a large primary care-based nested case-control study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 68, 1839–1842 (2009).

Weiss, R. J., Wick, M. C., Ackermann, P. W. & Montgomery, S. M. Increased fracture risk in patients with rheumatic disorders and other inflammatory diseases — a case-control study with 53,108 patients with fracture. J. Rheumatol. 37, 2247–2250 (2010).