Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of late pregnancy nicotine exposures, including secondhand smoke exposures, and to evaluate the associated risk of exposure to drugs of abuse.

Study Design:

The study was a retrospective single-center cohort analysis of more than 18 months. We compared self-reported smoking status from vital birth records with mass spectrometry laboratory results of maternal urine using a chi-square test. Logistic regression estimated adjusted odds for detection of drugs of abuse based on nicotine detection.

Results:

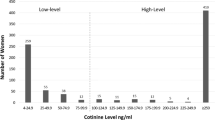

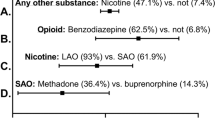

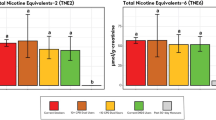

Compared with 8.6% self-reporting cigarette use, mass spectrometry detected high-level nicotine exposures for 16.5% of 708 women (P<0.001) and an additional 7.5% with low-level exposures. We identified an increased likelihood of exposure to drugs of abuse, presented as adjusted odds ratios, (95% confidence interval (CI), for both low-level (5.69, CI: 2.09 to 15.46) and high-level (13.93, CI: 7.06 to 27.49) nicotine exposures.

Conclusion:

Improved measurement tactics are critically needed to capture late pregnancy primary and passive nicotine exposures from all potential sources.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Aliyu MH, Lynch O, Saidu R, Alio AP, Marty PJ, Salihu HM . Intrauterine exposure to tobacco and risk of medically indicated and spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Perinatol 2010; 27 (5): 405–410.

Ko TJ, Tsai LY, Chu LC, Yeh SJ, Leung C, Chen CY et al. Parental smoking during pregnancy and its association with low birth weight, small for gestational age, and preterm birth offspring: a birth cohort study. Pediatri Neonatol 2014; 55 (1): 20–27.

Salihu HM, Aliyu MH, Pierre-Louis BJ, Alexander GR . Levels of excess infant deaths attributable to maternal smoking during pregnancy in the United States. Matern Child Health J 2003; 7 (4): 219–227.

Isayama T, Shah PS, Ye XY, Dunn M, Da Silva O, Alvaro R et al. Adverse impact of maternal cigarette smoking on preterm infants: a population-based cohort study. Am J Perinatol 2015; 32 (12): 1105–1111.

Markowitz S . The effectiveness of cigarette regulations in reducing cases of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. J Health Econ 2008; 27 (1): 106–133.

Mohsin M, Jalaludin B . Influence of previous pregnancy outcomes and continued smoking on subsequent pregnancy outcomes: an exploratory study in Australia. BJOG 2008; 115 (11): 1428–1435.

Castro LC, Azen C, Hobel CJ, Platt LD . Maternal tobacco use and substance-abuse - reported prevalence rates and associations with the delivery of small-for-gestational-age neonates. Obstet Gynecol 1993; 81 (3): 396–401.

McFarlane J, Parker B, Soeken K . Physical abuse, smoking, and substance use during pregnancy: prevalence, interrelationships, and effects on birth weight. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 1996; 25 (4): 313–320.

Tong VT, Dietz PM, Morrow B, D'Angelo DV, Farr SL, Rockhill KM et al. Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy—Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, United States, 40 sites, 2000-2010. MMWR Surveill Summ 2013; 62 (6): 1–19.

Pickett KE, Rathouz PJ, Kasza K, Wakschlag LS, Wright R . Self-reported smoking, cotinine levels, and patterns of smoking in pregnancy. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2005; 19 (5): 368–376.

Dukic VM, Niessner M, Pickett KE, Benowitz NL, Wakschlag LS . Calibrating self-reported measures of maternal smoking in pregnancy via bioassays using a Monte Carlo approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2009; 6 (6): 1744–1759.

Howland RE, Mulready-Ward C, Madsen AM, Sackoff J, Nyland-Funke M, Bombard JM et al. Reliability of reported maternal smoking: comparing the birth certificate to maternal worksheets and prenatal and hospital medical records, New York City and Vermont, 2009. Matern Child Health J 2015; 19 (9): 1916–1924.

Dietz PM, Homa D, England LJ, Burley K, Tong VT, Dube SR et al. Estimates of nondisclosure of cigarette smoking among pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age in the United States. Am J Epidemiol 2011; 173 (3): 355–359.

Tong VT, Althabe F, Aleman A, Johnson CC, Dietz PM, Berrueta M et al. Accuracy of self-reported smoking cessation during pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2015; 94 (1): 106–111.

Wickstrom R . Effects of nicotine during pregnancy: human and experimental evidence. Curr Neuropharmacol 2007; 5 (3): 213–222.

Evlampidou I, Bagkeris M, Vardavas C, Koutra K, Patelarou E, Koutis A et al. Prenatal second-hand smoke exposure measured with urine cotinine may reduce gross motor development at 18 months of age. J Pediatr 2015; 167 (2): 246–252 e242.

Ashford KB, Hahn E, Hall L, Rayens MK, Noland M, Ferguson JE . The effects of prenatal secondhand smoke exposure on preterm birth and neonatal outcomes. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2010; 39 (5): 525–535.

Benowitz NL . Cotinine as a biomarker of environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Epidemiol Rev 1996; 18 (2): 188–204.

Etzel RA . A review of the use of saliva cotinine as a marker of tobacco smoke exposure. Prev Med 1990; 19 (2): 190–197.

Benowitz NL, Hukkanen J, Jacob P 3rd . Nicotine chemistry, metabolism, kinetics and biomarkers. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2009; (192): 29–60.

Bernert JT Jr . McGuffey JE, Morrison MA, Pirkle JL . Comparison of serum and salivary cotinine measurements by a sensitive high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method as an indicator of exposure to tobacco smoke among smokers and nonsmokers. J Anal Toxicol 2000; 24 (5): 333–339.

Tuomi T, Johnsson T, Reijula K . Analysis of nicotine, 3-hydroxycotinine, cotinine, and caffeine in urine of passive smokers by HPLC-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chem 1999; 45 (12): 2164–2172.

Shin HS, Kim JG, Shin YJ, Jee SH . Sensitive and simple method for the determination of nicotine and cotinine in human urine, plasma and saliva by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2002; 769 (1): 177–183.

Dempsey D, Jacob P 3rd, Benowitz NL . Accelerated metabolism of nicotine and cotinine in pregnant smokers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 301 (2): 594–598.

Massatti R, Falb M, Yors A, Potts L, Beeghly C, Starr S . Neonatal abstinence syndrome and drug use among pregnant women in Ohio, 2004-2011. 2013. Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services.: Columbus, OH.

Wexelblatt SL, Ward LP, Torok K, Tisdale E, Meinzen-Derr JK, Greenberg JM . Universal maternal drug testing in a high-prevalence region of prescription opiate abuse. J Pediatr 2015; 166 (3): 582–586.

Hall ES, Meinzen-Derr J, Wexelblatt SL . Cohort analysis of a pharmacokinetic-modeled methadone weaning optimization for neonatal abstinence syndrome. J Pediatr 2015; 167 (6): 1221–1225 e1221.

Haufroid V, Lison D . Urinary cotinine as a tobacco-smoke exposure index: a minireview. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 1998; 71 (3): 162–168.

Balhara YP, Jain R . A receiver operated curve-based evaluation of change in sensitivity and specificity of cotinine urinalysis for detecting active tobacco use. J Cancer Res Ther 2013; 9 (1): 84–89.

Ohio Department of Health. Mother’s worksheet for child’s birth. 2014 [cited February 18, 2016] Available from http://vitalsupport.odh.ohio.gov/gd/gd.aspx?Page=3&TopicRelationID=306&Content=5994.

American Cancer Society. Guide to quitting smoking 2014 [cited May 18, 2016] Available from http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/002971-pdf.pdf.

Song YM, Sung J, Cho HJ . Reduction and cessation of cigarette smoking and risk of cancer: a cohort study of Korean men. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26 (31): 5101–5106.

Cradle Cincinnati. Our families, our future. 2015 [cited April 8, 2016] Available from http://www.cradlecincinnati.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Annual-Report-2015-Compressed.pdf.

Farsalinos KE, Polosa R . Safety evaluation and risk assessment of electronic cigarettes as tobacco cigarette substitutes: a systematic review. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2014; 5 (2): 67–86.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 471: Smoking cessation during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2010; 116 (5): 1241–1244.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) core questionnaire with optional questions. Version 1.0. 2012 [cited May 5, 2016] Available from http://nccd.cdc.gov/GTSSData/Ancillary/DownloadAttachment.aspx?ID=33.

SAMHSA. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2008-2011. 2012 [cited May 18, 2016] Available from http://archive.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2011SummNatFindDetTables/NSDUH-DetTabsPDFWHTML2011/2k11DetailedTabs/Web/HTML/NSDUH-DetTabsSect6peTabs55to107-2011.htm#Tab6.71B.

Patrick SW, Davis MM, Lehmann CU, Cooper WO . Increasing incidence and geographic distribution of neonatal abstinence syndrome: United States 2009 to 2012. J Perinatol 2015; 35 (8): 650–655.

Acknowledgements

This study includes data provided by the Ohio Department of Health, which should not be considered an endorsement of the study or its conclusions. This work was supported by the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Perinatal Institute, Cradle Cincinnati, and by a gift from Amgis Foundation Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Journal of Perinatology website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hall, E., Wexelblatt, S. & Greenberg, J. Self-reported and laboratory evaluation of late pregnancy nicotine exposure and drugs of abuse. J Perinatol 36, 814–818 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.100

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.100

This article is cited by

-

Maternal exposure to childhood maltreatment and adverse birth outcomes

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Low level of urinary cotinine in pregnant women also matters: variability, exposure characteristics, and association with oxidative stress markers

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023)

-

Smoking cessation in pregnant women using financial incentives: a feasibility study

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2022)

-

Rates of substance and polysubstance use through universal maternal testing at the time of delivery

Journal of Perinatology (2022)

-

Regional comparison of self-reported late pregnancy cigarette smoking to mass spectrometry analysis

Journal of Perinatology (2021)