Abstract

Reticulate evolution, introgressive hybridisation, and phenotypic plasticity have been documented in scleractinian corals and have challenged our ability to interpret speciation processes. Stylophora is a key model system in coral biology and physiology, but genetic analyses have revealed that cryptic lineages concealed by morphological stasis exist in the Stylophora pistillata species complex. The Red Sea represents a hotspot for Stylophora biodiversity with six morphospecies described, two of which are regionally endemic. We investigated Stylophora species boundaries from the Red Sea and the associated Symbiodinium by sequencing seven DNA loci. Stylophora morphospecies from the Red Sea were not resolved based on mitochondrial phylogenies and showed nuclear allele sharing. Low genetic differentiation, weak isolation, and strong gene flow were found among morphospecies although no signals of genetic recombination were evident among them. Stylophora mamillata harboured Symbiodinium clade C whereas the other two Stylophora morphospecies hosted either Symbiodinium clade A or C. These evolutionary patterns suggest that either gene exchange occurs through reticulate evolution or that multiple ecomorphs of a phenotypically plastic species occur in the Red Sea. The recent origin of the lineage leading to the Red Sea Stylophora may indicate an ongoing speciation driven by environmental changes and incomplete lineage sorting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The distributions of several tropical marine species overlap in an area of maximum marine biodiversity located in the Indo-Malay Archipelago known as the Coral Triangle1. However, recent works on different reef organisms demonstrated that some peripheral regions, such as the Red Sea2,3,4,5 and the Hawaiian Archipelago4,5,6, can act as biodiversity sources, exporting both genetic diversity and morphological novelties7. For example, the epicentre of global scleractinian coral diversity is located in the Coral Triangle, but two important and separate centres of biodiversity occur in the Red Sea3 and in the subequatorial Western Indian Ocean8,9. Both these biodiversity centres are characterised by high levels of endemism3,9,10 and, notably, molecular studies have revealed unexpected phylogenetic patterns, unique haplotypes, and endemic taxa that were previously hidden by traditional approaches of species identification based on the study of skeleton morphology11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. In particular, the Red Sea harbours a large number of coral species3,8,19,20 and the highest level of endemism in the Indian Ocean region8. Specifically, 5.5% of the 346 species recorded in the Red Sea are endemic3,21 whereas levels of endemism are less than 2% for the other areas of the Indian Ocean8. The relatively high number of endemic species in the Red Sea may reflect its unusual environmental conditions (e.g., high temperature and salinity22) and seems to have multiple origins21. Indeed, some taxa diverged from their Indian Ocean counterparts long before the most recent glaciations21,23 while other taxa may have originated from glacial refugia within the Red Sea2,4,5,21.

Accurate evaluations of diversity rely on adequate species identification, a non-trivial issue for corals. Two critical challenges are the presence of cryptic species14,15,16,24,25,26,27,28, derived from either evolutionary convergence (two non-sister species independently evolve the same phenotype) or morphological stasis (two sister species acquire the same phenotype from a common ancestor), and the occurrence of phenotypic plasticity (the capacity of a single genotype to produce different phenotypes in response to varying environmental conditions)29,30. Genetic surveys within different coral genera, such as Stylophora14,15,17, Acropora16,24,25, Pocillopora26,27, and Seriatopora28, have revealed unexpected cryptic diversity in both sympatric and allopatric populations and over relatively small (e.g., Great Barrier Reef 28, American Samoa26, or Western Australia27) and relatively large (e.g., Indo-Pacific Ocean14,16,17,24) areas. Phenotypic plasticity is a trait often associated with corals and poses many challenges for the reliable identification of these animals29. Environmental factors can shape coral colonies and greatly increase intraspecific morphological variation, making the delimitation of species boundaries a difficult task29,30.

Zooxanthellate scleractinian corals of the genus Stylophora are widely distributed and abundant throughout the tropical and sub-tropical coral reef communities of the Indo-Pacific, from the Red Sea to French Polynesia31. Their branching coralla and growth forms are highly plastic in relation to environmental gradients dynamically shaping the colonial architecture32. Stylophora corals are relatively easy to maintain in aquaria and they can produce asexual propagules. The combination of these features has led to the use of Stylophora corals, and in particular of S. pistillata, as a key model system for scleractinian reproduction33, physiology34, phenotypic plasticity32, coral-dinoflagellate symbiosis35, and transcriptome36 studies. Nevertheless, recent genetic surveys based on a combination of mitochondrial and nuclear loci have revealed the presence of cryptic divergence and four evolutionary distinct lineages within S. pistillata across its entire distribution range14,17. These data caution that general conclusions arising from comparative investigations of the “lab-rat” S. pistillata might be biased by the inclusion of different cryptic entities into experimental designs14. Indeed, molecular phylogenies demonstrated the existence of a single homogenous and highly-connected species across the eastern Indian Ocean and the entire Pacific Ocean (clade 1)14,37, and at least three distinct entities within the western Indian Ocean and the Red Sea (clades 2, 3, and 4)14,15,17. Although the phenotypic plasticity of S. pistillata is well documented and greatly contributed to the taxonomic confusion that characterised the genus31,32, three deeply divergent genetic lineages of S. pistillata (clades 1, 2, and 4)14 showed similar skeletal morphology and a comparable range of phenotypic variation as result of morphological stasis over a period of 30–50 million years14,17. On the contrary, clade 3 corresponded unambiguously to S. madagascarensis and it is morphologically recognisable from the other three groups at the corallite level15. Moreover, differences in associated algal endosymbionts (Symbiodinium) were detected among the four lineages14, suggesting that different regional environments might influence the ecology of this symbiosis38,39.

These genetic data corroborated the traditional thought, based on morphological criteria19,20,31, that Stylophora displays its peak of diversity in the western and northern Indian Ocean. In particular, Stylophora corals from the seas around the Arabian peninsula show remarkable variability in colony morphology and growth form, with a total of six morphospecies assumed to live in this area, namely S. pistillata, S. subseriata, S. danae, S. kuehlmanni, S. mamillata, and S. wellsi31. Interestingly, S. danae and S. kuehlmanni seem to be endemics of the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea, whereas S. mamillata and S. wellsi are restricted to the Red Sea20,31, suggesting that the ancestral species of the genus Stylophora originated in the Red Sea10. On the one hand, genetic and morphological data demonstrated that S. danae, S. kuehlmanni, and S. subseriata from the Gulf of Aden belong to clade 414 and likely represent ecomorphs of S. pistillata determined by variation in wave movement and light intensity15,20. On the other hand, S. mamillata and S. wellsi display encrusting growth forms with knobby-lobbed verrucae distinguishing them from other Stylophora species19,20 but no genetic data from these two species are available to date. Moreover, S. mamillata grows on shaded reef slopes between 20 and 40 m depth, S. wellsi occurs in very shallow water of exposed fringing reefs with strong swell and water action20, and S. pistillata lives in a wide range of habitats and depths19. The latter species shows high phenotypic plasticity, exhibiting thick, short branches when growing in shallow, wave-exposed environments and developing slender and anatomising colonies in deeper, protected water19,31.

In this study, we attempted to assess whether the Red Sea represents a biodiversity hotspot for the coral genus Stylophora, integrating new sequence data from this region with previously published phylogenies14,15,17,37. A large collection of Stylophora samples from different localities along the Saudi Arabian Red Sea (spanning about 2,000 km coastline) was obtained, including colonies from each of the six morphospecies reported to co-occur in the region. Their phylogenetic relationships and the amount of genetic differentiation were investigated, with a particular focus on the Red Sea endemic morphospecies S. mamillata and S. wellsi31. We sequenced three mitochondrial and three nuclear DNA regions previously employed to detect cryptic speciation in S. pistillata14,15,17,37, as well as one plastid locus from the associated symbiotic dinoflagellates Symbiodinium40. Our specific aims were to define the genetic boundaries and isolation among S. mamillata, S. wellsi, and S. pistillata in the Red Sea and to evaluate the timing of the origin of the extant Red Sea Stylophora endemics. On the basis of the obtained data, we discuss whether S. mamillata, S. wellsi, and S. pistillata might represent multiple ecomorphs of a single phenotypically-plastic species or a species complex in the early stages of speciation. The possible roles of phenotypic plasticity, reticulate evolution, introgressive hybridisation, and incomplete lineage sorting are evaluated, and possible causes of the recent diversification of these morphospecies in the Red Sea are proposed.

Results

Phylogenetic and haplotype network analyses

We obtained sequence data from three mitochondrial regions, namely the barcoding portion of the cytochrome oxidase I gene (COI), the putative control region (CR), and an open reading frame of unknown function (ORF), along with three nuclear loci, namely the internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1) and 2 (ITS2) of ribosomal DNA and the heat shock protein 70 gene (HSP70). Sequences were obtained for each locus from all 103 Stylophora colonies sampled across the Red Sea with the exception of three specimens that were not genetically characterised at the ITS1 and ITS2 regions (Tables 1 and 2, Data S1). The single-locus phylogenies based on COI and CR clustered all the analysed Stylophora specimens from the Red Sea within clade 4; these further clustered with published sequences of S. pistillata from the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea (Fig. 1). Notably, the COI phylogeny showed that Stylophora is not monophyletic due to the inclusion of Seriatopora (Fig. 1) as previously reported14. The main discrepancy among the three proposed mitochondrial phylogenies was related to the phylogenetic topology inferred from ORF, where clade 4 was split into two main lineages. Of these two lineages, the most divergent one was composed only of colonies from both the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden identified as belonging to the “S. pistillata” complex without any S. mamillata and S. wellsi samples (Fig. 1C). Mitochondrial haplotype networks suggested that all specimens of S. mamillata and S. wellsi shared a single ancestral haplotype for the CR locus that was also found in most “S. pistillata” complex samples from the Red Sea, while the two former species showed separated haplotypes for the ORF region (Fig. S1). For both mitochondrial loci, sequences of “S. pistillata” complex from clade 4 presented several different haplotypes, some of which were highly divergent from the majority of the remaining haplotypes.

Mitochondrial Bayesian phylogenetic tree reconstructions of the genus Stylophora.

(A) cytochrome oxidase I gene, (B) putative control region, (C) open reading frame of unknown function. Values at branches represent posterior Bayesian probabilities (>0.7), ML SH-like support (>70%), and MP bootstrap values (>70%), respectively. Dashes (−) indicate nodes that are statistically unsupported. Sequences obtained in this study are indicated in bold. Colours denote Stylophora morphospecies as indicated by the embedded key. Clade numbers follow designations of14.

The phasing of heterozygous nuclear loci was consistent and multisite heterozygotes were resolved with confidence, showing P > 0.8 for all the analysed Stylophora individuals. We always detected a maximum of two predominant ITS1 and ITS2 sequences in each of the collected specimens, and therefore these two nuclear loci were considered as single-copy nuclear genes (as is HSP70) and each individual was considered either homozygous or heterozygous for these two DNA regions37,41. Nuclear loci were more diverse than mitochondrial ones in terms of haplotype number, haplotype diversity, and nucleotide diversity (Table 1). Although ITS115,17, ITS217, and HSP70 (Fig. S2) resolved S. pistillata as a complex of four deeply divergent clades, the nuclear loci grouped the Stylophora morphospecies colonies from the Red Sea in a single lineage (clade 4) (Figs 2 and 3). The nuclear haplowebs revealed pervasive allele sharing among Stylophora morphospecies from the Red Sea included in clade 4 (Figs 2 and 3). No clear clusters or cohesive groups of individuals sharing a common allele pool were detected across Stylophora morphospecies; alleles belonging to each species were highly dispersed across the three nuclear haplowebs. A clear overlap of intra- and interspecific genetic distances was observed in each of the three nuclear loci (Table 3).

Haplowebs of Stylophora morphospecies belonging to clade 4 based on nuclear rDNA.

(A) ITS1, (B) ITS2. Each circle represents a haplotype and its size is proportional to its total frequency. Coloured lines connect haplotypes of heterozygotes individuals and colours denote Stylophora morphospecies as indicated by the embedded key. Small grey circles represent missing haplotypes and small orange circles represent a single nucleotide change.

Haplowebs of Stylophora morphospecies belonging to clade 4 based on nuclear HSP70 gene.

Each circle represents a haplotype and its size is proportional to its total frequency. Coloured lines connect haplotypes of heterozygotes individuals and colours denote Stylophora morphospecies as indicated by the embedded key. Small grey circles represent missing haplotypes and small orange circles represent a single nucleotide change.

Symbiodinium clade association

High-quality Symbiodinium sequences of a ~300 bp portion of the plastid psbA gene (psbA) were obtained from a subset of Stylophora specimens (n = 64), without showing any signal of polymorphisms40. Based on the psbA analysis, all the sampled colonies of Stylophora from the Red Sea harboured either Symbiodinium clades A or C (Fig. 4). In detail, Symbiodinium associated to S. mamillata belonged exclusively to clade C. Stylophora wellsi and “S. pistillata” complex hosted either clades A (n = 22) or C (n = 17), and their Symbiodinium composition seemed to be unrelated to the north-south latitudinal gradient of the Red Sea (Fig. 4).

Distribution of Symbiodinium clades across the analysed S. mamillata, S. wellsi, and “S. pistillata” complex (on the left) and across the Red Sea (on the right) based on psbA.

Circles in the map refer to the sampling sites of Stylophora corals (Data S1) and are proportional to the number of analysed colonies. The circle colours refer to Symbiodinium clade A (light grey) and clade C (dark grey). The map was created using Natural Earth (http://www.naturalearthdata.com) and QuantumGIS 2.12 (Quantum GIS Development Team, www.qgis.org).

Population genetic and recombinant analyses

The amount of genetic isolation and differentiation among “S. pistillata” complex, S. mamillata, and S. wellsi was estimated using the hierarchical Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) analysis and pairwise FST comparisons, assuming each species as a single population and using each of the three individual nuclear loci. The AMOVA results showed no genetic structuring and isolation among species for ITS2 and HSP70 whereas FCT was significant for ITS1 (Table 4). Indeed, only a small fraction of the genetic variation was explained by the species grouping (19.34% for ITS1, 6.29% for ITS2, and 9.12% for HSP70); most variance occurred within or among individuals (Table 4). Estimated pairwise FST values were not significantly different from 0 in all comparisons except between the “S. pistillata” complex and S. mamillata based on HSP70 (Table 5). Collectively, the AMOVA analysis and the pairwise FST values suggested that the three Stylophora species were genetically indistinguishable from each other and that limited genetic isolation has occurred.

An analysis of potential recombinant events was conducted to test for hybridization signals among the sequenced nuclear loci, but no evidence of recombination was observed in the three analysed nuclear loci.

Divergence time estimation

The multi-locus time-calibrated phylogeny of the genus Stylophora was inferred from the concatenated mitochondrial and nuclear datasets for a total of 5,410 bp (Fig. 5). Divergence times between the main Stylophora clades and their 95% highest posterior density (HPD) intervals were estimated using the earliest fossil record of the genus from Santonian and Oman, i.e. the appearance of Stylophora octophyllia 65.5–70 Ma42,43. The group containing the three Stylophora species from the Red Sea (“S. pistillata” complex, S. mamillata, and S. wellsi) was estimated to be the most recent lineage within the entire genus, originating 2.51 Ma (95% HPD: 0.56–4.46 Ma). Finally, the estimated divergence times between clades 1 and 2 and between clades 3 and 4 were 19.56 ± 13.71 Ma and 31.84 ± 14.95 Ma, respectively.

Multi-locus time-calibrated phylogeny reconstruction of the genus Stylophora inferred from the concatenated dataset (COI, CR, ORF, ITS1, ITS2, and HSP70) analysed using BEAST.

The orange circle marks the node that was time-constrained with fossil (the first appearance of S. octophyllia in Santonian and Oman) as described in the text. Values above nodes are mean node ages and orange bars display the 95% highest posterior density (HPD) interval of node ages. Values under nodes are posterior probabilities (>0.9). Clade numbers refer to14. Colours in the map are the same as used in the time-calibrated phylogeny on the left. The map was created using Natural Earth (http://www.naturalearthdata.com) and QuantumGIS 2.12 (Quantum GIS Development Team, www.qgis.org).

Discussion

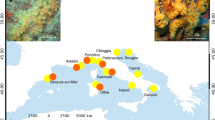

In this study we evaluated the importance of the Red Sea as a biodiversity hotspot for the coral genus Stylophora, including specimens representing all six morphospecies reported to occur in sympatry in this region (Fig. 6)19,31. In contrast to expectations based on traditional taxonomy19,31, the molecular data reported here suggested the presence of a single highly-connected genetic unit of Stylophora in this region. These results contradicted the assumption that the Red Sea represents a biodiversity hotspot for Stylophora and supported the western Indian Ocean as centre of diversity and origin9,10, given the co-occurrence of at least three deeply divergent genetic entities in the latter area14,17. Five DNA markers (COI, CR, ITS1, ITS2, and HSP70) gave congruent results and confirmed the presence of four genetically isolated clades in Stylophora across its entire geographic distribution14. However, all Stylophora corals from the Red Sea belonged to a single molecular clade together with samples from the Gulf of Aden15, and the Red Sea morphospecies were indistinguishable on the basis of these five variable and phylogenetically informative loci (COI, CR, ITS1, ITS2, and HSP70). Conversely, the phylogenetic topology inferred from ORF partitioned S. pistillata specimens from the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden in two non-sister clades (Fig. 1C). The discordance among mitochondrial DNA markers has been previously discussed15 and is potentially caused by pseudogenes in the mitochondrial genome of some corals, as similarly detected in fish44. This scenario may also explain the high values of haplotype and nucleotide diversity in comparison to those found in the other mitochondrial and nuclear loci (Table 1). In fact, genetic diversity among the analysed Stylophora morphospecies from the Red Sea (the interspecific genetic distances based on ITS1, ITS2, and HSP70) was among the lowest ever documented in corals, <1% in all pairwise comparisons45. Notably, although the Red Sea endemic species S. mamillata and S. wellsi are easily recognisable based on colony morphology and distinct depth distributions19,20,31, extensive gene flow occurred between these two morphospecies and with S. pistillata. Finally, the time-calibrated phylogeny of the genus Stylophora demonstrated that the clade leading to the Red Sea morphospecies originated recently, i.e. 2.51 Ma (95% HPD: 0.56–4.46 Ma).

Variability of in-vivo colony appearance and skeleton morphology of Stylophora morphospecies from the Red Sea.

(A–D) S. mamillata SA432 and SA433, (E–H) S. wellsi SA371 and SA731, (I–T) “S. pistillata” complex: (I,J) S. danae SA730, (K,L) S. subseriata SA1500, (M,N) S. pistillata SA1743, (O,P) S. kuehlmanni SA1757, (Q,R) S. pistillata SA1546, showing verrucae typical of Pocillopora, (S,T) S. pistillata “mordax” form SA1241. Colours refer to S. mamillata (green), S. wellsi (blue), and “S. pistillata” complex (black). Scale bars 1 cm.

The incongruence between morphological species delimitations and genetic species boundaries is striking and may be caused by several factors. The collected colonies of S. pistillata, S. danae, S. subseriata, and S. kuehlmanni exhibit a smooth morphological continuum with regard to the skeletal features traditionally used to identify these taxa19,31. For example, the branch thickness, the presence of corallite hood, and the coenosteum formation can extensively vary on a single corallum and can be shaped by environmental conditions. Considering the absence of interspecific genetic differentiation based on the six molecular loci employed in this study14,15,16,17,24,25,26,27,28,37, the latter three morphospecies should be considered as junior synonyms of S. pistillata, as suggested in previous studies15,20. The Red Sea is characterised by strong latitudinal gradients in environmental variables (e.g., temperature, salinity, and nutrients)22, by a great diversity of habitats and reefs3, and by a complex geological history21,46. These aspects, combined with the extreme phenotypic plasticity29,32 and habitat generalisation33,34 documented in S. pistillata, can possibly explain the outstanding phenotypic polymorphism of this species in the region.

Despite the lack of genetic differentiation, S. mamillata and S. wellsi show distinct colony morphologies and depth-partitioning19,20,31. There are at least two possible scenarios that could explain semi-permeable species boundaries among “S. pistillata” complex, S. mamillata, and S. wellsi. Stylophora mamillata and S. wellsi may be regional ecomorphs of the highly phenotypic plastic S. pistillata or they may actually be valid species. If the latter, they remain connected through genetic exchange or they may be examples of recent speciation events. The first hypothesis (i.e., S. mamillata and S. wellsi are ecomorphs of S. pistillata) is supported by the extreme phenotypic plasticity of S. pistillata in the Red Sea29,32. A single genotype can produce different phenotypes in response to changing environmental and selective regimes30, resulting in distinct morphologies influenced by depth, light, and wave action. For example, a translocated colony of P. meandrina began to grow with a morphology more similar to P. damicornis after several months47; similar translocation experiments could be carried out for S. mamillata and S. wellsi. Colony morphology is known to be a misleading character in the identification of several corals11,13,17,24,19,31. The encrusting S. mamillata is usually characterised by nodes thought to be incipient branches, but these can sometimes grow into small clear branches. Similarly, the formation of verrucae is one of the morphological features prescribed to diagnostically identify S. wellsi among Stylophora species, but some analysed colonies of S. pistillata show this peculiar structure (Fig. 6). Under the second scenario (i.e., S. mamillata and S. wellsi are valid species), reticulate evolution through hybridisation and gene exchange or incomplete lineage sorting due to recent speciation may explain the genetic data. Although no recombinant events were detected in the obtained nuclear sequences, introgressive hybridisation and gene exchange have been extensively documented in closely related scleractinian corals. This can be promoted by extensive sympatry and simultaneous multispecies spawning24,48,49,50,51,52. Interestingly, a case of hybridisation between Pocillopora damicornis and S. pistillata was demonstrated in an isolated island of Australia48, as well as among Pocillopora species in the Pacific Ocean50. These findings suggest that prezygotic isolating mechanisms in the pocilloporids are permeable and may also provide chances for introgression in Stylophora. whose morphospecies in the Red Sea may form a Stylophora syngameon (a group of species connected through genetic exchange). Moreover, it is widely accepted that hybridisation is enhanced in isolated and peripheral regions7,51,52, such as the Red Sea3,21, and novel hybrids may have advantageous reproductive abilities48. The second process (incomplete lineage sorting) is supported by the time-calibrated phylogeny of Stylophora. The phylogenetic reconstruction dated the diversification of the extant Red Sea morphospecies to 2.51 Ma (95% HPD: 0.56–4.46 Ma), matching the period of the establishment of the Red Sea reef fauna21. During this time of the Pliocene and Pleistocene (3–4 Ma)21, extreme environmental variations occurred, such as fluctuations in temperature and salinity22. Moreover, the divergence times between clades 1 and 2 (19.56 ± 13.71 Ma) and between clades 3 and 4 (31.84 ± 14.95 Ma) are in agreement with the evidence of multiple centres of origins for Indian Ocean corals occurring in the Palaeogene and Neogene Tethys, as hypothesised based on the geological events and the distribution of coral endemism in this area9,10. Therefore, the obtained time-calibrated phylogeny strengthens the hypothesis that suggested the isolation of distinct Stylophora populations as a result of the fragmentation of the Tethys Sea, which promoted a great diversification of the genus in the Indian Ocean3.

On the basis of these results, S. mamillata, S. wellsi, and S. pistillata may represent a species complex undergoing early speciation that still shares most ancestral alleles and polymorphisms. The rapid speciation of the three recent morphospecies of Stylophora might have been promoted by the strong environmental changes encountered in the Red Sea during Pliocene and Pleistocene21,46, which may have favoured niche partitioning and ecological differentiation. Furthermore, the extreme phenotypic plasticity of S. pistillata might have played a crucial role in promoting speciation, creating intraspecific variations that can form the basis for interspecific diversification30. Furthermore, although no genetic isolation was detected among “S. pistillata” complex, S. mamillata, and S. wellsi, they might remain recognisable because disruptive selection may be occurring53 or because hybridisation is not pervasive5. Indeed, the three morphospecies are ecologically differentiated, showing distinct habitat preference and depth partitioning and, in this condition, disruptive selection can contribute to the maintenance of ecological differences among species and increased phenotypic variation49,53.

Coevolution of the coral host and symbiont dinoflagellate Symbiodinium may play a significant role in niche specialisation, habitat partitioning, and ecological diversification of corals. It may also promote speciation events54,55. Previous studies on brooding corals of the genera Madracis and Agaricia across a large depth gradient (2–60 m depth) demonstrated that their associated Symbiodinium consistently revealed patterns of host specificity and depth-based zonation49,56, shaping host bathymetric distribution and ecology. Stylophora corals in the Red Sea hosted either Symbiodinium clades A or C and, interestingly, all the “deep-water specialist” S. mamillata colonies harboured exclusively Symbiodinium clade C, whereas the “shallow-water specialist” S. wellsi and the generalist “S. pistillata” complex were associated with Symbiodinium clades A and C along the entire Saudi Arabian Red Sea (spanning 13° of latitude from the Gulf Aqaba to the Farasan Islands). Previous investigations of S. pistillata from the Red Sea demonstrated associations with Symbiodinium clades A, C, or A + C combinations14 and, in particular, it shifts from hosting mainly Symbiodinium clade A in shallow waters (2–6 m depth) to Symbiodinium clade C in deeper waters (24–26 m depth) in the Gulf of Aqaba (northern Red Sea)35. Nevertheless, Symbiodinium data presented in this study are not exhaustive and further detailed analyses based on ITS2 typing via next generation sequencing approaches are needed57 to clarify if there is a specific association between S. mamillata and Symbiodinium clade C, which may suggest adaptation of this symbiosis to deep water (below 20 m depth).

Conclusions

Despite the presence of distinct colony morphologies, Stylophora corals from the Red Sea belong to a single cohesive molecular lineage and host less genetic variability compared to other regions, such as the western Indian Ocean and the Gulf of Aden, where up to three genetic clades occur in sympatry14,15,17. These results raise several questions concerning the evolution of the extant Styophora morphospecies in the Red Sea. Further analyses are needed in order to evaluate whether S. mamillata and S. wellsi represent either valid endemic species arising from recent speciation or whether they are simply local ecomorphs of the common “S. pistillata” complex adapted to distinct depth and light conditions. Indeed, single and multi-gene approaches may be affected by the slow evolution rate of coral mitochondrial DNA58 and by the incomplete concerted evolution of rDNA59, resulting in low genetic variation levels of the analysed loci. In these cases, the application of reduced genome approaches, such as RNA-seq or RAD-tag seq, will provide a genome-wide perspective and may improve the phylogenetic resolution and species boundaries definitions, as already demonstrated in the scleractinian coral Pocillopora44 and the octocoral Chrysogorgia60. A closer investigation of the reproductive modes in S. mamillata and S. wellsi may provide insights into the possible occurrence of reproductive barriers and the role of hybridisation events among these morphospecies. Finally, translocation experiments of S. mamillata and S. wellsi in different depths and environmental regimes will enhance the understanding of phenotypic plasticity and polymorphism whereas associated transcriptomic analyses might indicate which genes are involved in these mechanisms.

Methods

Coral collection and identification

A total of 106 colonies of Stylophora corals were collected along the coast of the Saudi Arabian Red Sea, between 1–40 m depth. Furthermore, four specimens of S. pistillata from Papua New Guinea (clade 1), one colony of S. pistillata from Madagascar (clade 2), and one sample of S. madagascarensis from Madagascar (clade 3) were included in the analyses. Each colony was photographed underwater and tagged (Data S1). A small portion of tissue (~2 cm3) was preserved in 95% ethanol for molecular analyses while the remaining portion (~10 cm3 of the colony) was bleached in sodium hypochlorite, rinsed with fresh water, and air-dried. Morphospecies identification was achieved by examining type material and reference monographs19,20,31. For analyses, we considered S. pistillata, S. subseriata, S. danae, and S. kuelhmanni as part of a single lineage (indicated in the text as “S. pistillata” complex), corresponding to Stylophora morphs M and L15, and clade 414. Indeed, these four species in the Red Sea “form a smooth continuum with regard to those skeletal structures which have been used previously to help establish them”20. On the contrary, S. mamillata and S. wellsi are easily morphologically distinguishable from the above four morphospecies, and were therefore treated as separate entities20 (Fig. 6).

DNA extraction and PCR amplifications

Genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and DNA concentration of extracts was quantified using a Nanodrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). A total of six loci were amplified and sequenced for the analysed Stylophora morphospecies14,15,17,37: COI, CR, and ORF from the mitochondrial genome, and ITS1, ITS2, and HSP70 gene from nuclear DNA. Symbiodinium clades of Stylophora hosts were identified using the plastid psbA minicircle (psbA)40. The list of primers and PCR annealing temperature is indicated in Table S1. Amplifications were performed in a 12.5 μl PCR reaction mix containing 0.2 μM of each primer, 1X Multiplex PCR Master Mix (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and <0.1 ng DNA. PCR consisted of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 sec, annealing for 1 min, extension at 72 °C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. All PCR products were purified with Illustra ExoStar (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) and directly sequenced in both directions using an ABI 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). All sequences generated as part of this study were deposited in the EMBL database (Data S1).

Phase determination, sequence alignment, and recombination assessment

Forward and reverse sequences were assembled and edited using Sequencher 5.3 (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Most Stylophora colonies showed double peaks and intra-individual polymorphisms from nuclear loci and were thus considered to be heterozygotes41. Nuclear sequences were phased using SeqPHASE61 and Phase62 when alleles showed the same length (n = 21 for ITS1, n = 12 for ITS2, and n = 62 for HSP70), and using Champuru63 if the two predominant alleles were of different length (n = 40 for ITS1 and n = 68 for ITS2). In the former case, the two alleles with the highest probability (an order of magnitude greater than the other sequence pairs) were chosen whenever there were multiple possible phases. No obvious or significant differences of genetic diversity and haploweb inference were obtained using alternative phases (results not shown). Alleles of different length were detected only in the ITS1 and ITS2 regions. Phased heterozygotes were represented by both alleles in the further alignments and population genetic analyses. Alignments for each individual locus were performed using MAFFT 7.130b64 and the iterative refinement method E-INS-i. Determination of potential recombinant events that can be interpreted as significant signals of hybridisation was carried out using RPD465 for each of the three nuclear loci. In particular, the algorithms RDP, GENECONV, BootScan, MaxChi, Chimaera, SiScan, LARD, and 3SEQ were investigated using the default settings in all cases.

Phylogenetic and haplotype network analyses

General statistics concerning the obtained sequences and the variability of the seven employed markers were calculated with DnaSP 5.10.166, as reported in Tables 1 and 2. The best evolutionary model for each individual molecular locus was selected using jModeltTest 2.1.167, as indicated in Table S1. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted under three criteria (Bayesian inference (BI), maximum likelihood (ML), and maximum parsimony (MP)) for each of the three individual mitochondrial regions (COI, CR, and ORF) and the nuclear HSP70 gene. For BI analyses, four Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains were run for 8 million generations in MrBayes 3.2.168, saving a tree every 1,000 generations. The analyses were stopped when the deviation of split frequencies was less than 0.01 and all parameters were checked in Tracer 1.669 for effective sampling size and unimodal posterior distribution. The first 25% trees sampled were discarded as burn-in following indications by Tracer 1.6. ML topology was reconstructed using PhyML 3.070 using the Shimodaira and Hasegawa test (SH-like) to check the support of each internal branch. MP analysis was performed using PAUP 4.0b1071 and a heuristic search strategy with tree-bisection-reconnection (TBR) branch swapping for 100 replicates and random stepwise addition. Node support was assessed throughout 1,000 bootstrap replicates. The median-joining network analysis implemented in Network 4.61372 was applied to each of the three nuclear datasets and to the highly variable mitochondrial CR and ORF regions in order to evaluate relationships among haplotypes. In order to find groups of individuals sharing a common allele pool, nuclear haplonets were converted into haplowebs73 by drawing additional connections between the two haplotypes co-occurring in heterozygous individuals using Network Publisher 2.0.0.1 (Fluxus Technology, Suffolk, UK).

Population genetic analyses

A hierarchical Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) was performed using Arlequin 3.5.1.274 to determine the percentage of genetic variance explained by morphospecies clustering and the significance of population structure among and within the analysed Stylophora morphospecies (subdivided as “S. pistillata” complex, S. mamillata, and S. wellsi), assuming each of the three morphospecies as a population. The genetic differentiation among taxa was estimated by means of pairwise FST with Arlequin 3.5.1.2, calculated with Slatkin’s distance and using genetic distances corrected by a Kimura two-parameter evolutionary model. Significance was tested using 1,000 permutations and allowing a minimum P-value of 0.05. Intra- and interspecific genetic distances were calculated using DnaSP 5.10.1 under a Kimura two-parameter evolutionary model and variance was estimated with 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

Divergence time estimation

In order to provide a provisional estimate of the divergence time of each of the Stylophora clades and of the Red Sea Stylophora morphospecies, a time-calibrated phylogenetic hypothesis was inferred under a Bayesian framework using BEAST 1.8.275, based on the complete concatenated mitochondrial and nuclear dataset (5,410 bp). We specified the same six partitions as above with unlinked evolutionary models, an uncorrelated (lognormal) clock model, and a Yule tree prior. The analysis was run for 50 million generations, with a sampling frequency of 1,000. After checking adequate mixing and convergence of all runs with Tracer 1.669, the first 20% trees were discarded as burn-in and a maximum clade credibility chronogram with mean node heights was computed using TreeAnnotator 1.8.275. It is known that Stylophora occurred both in the Caribbean and the Indo-Pacific during the late Cretaceous but then it disappeared from the former basin during the early Miocene20. Because the genus occurs today only in the Indo-Pacific, we time-constrained the node leading to Stylophora spp in the tree based on the fossil record of S. octophyllia, which first appear in Santonian and Oman during the Maastrichtian around 65.5–70 Mya43,44.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Arrigoni, R. et al. Recent origin and semi-permeable species boundaries in the scleractinian coral genus Stylophora from the Red Sea. Sci. Rep. 6, 34612; doi: 10.1038/srep34612 (2016).

References

Hoeksema, B. W. Delineation of the Indo-Malayan centre of maximum marine biodiversity: the Coral Triangle. In Biogeography, time, and place: distributions, barriers, and islands (ed. Renema, W. ) 117–178 (Springer, Dordrecht, 2007).

DiBattista, J. D. et al. Blinded by the bright: a lack of congruence between colour morphs, phylogeography and taxonomy for a cosmopolitan Indo‐Pacific butterflyfish, Chaetodon auriga. Journal of Biogeography 42, 1919–1929 (2015).

DiBattista, J. D. et al. A review of contemporary patterns of endemism for shallow water reef fauna in the Red Sea. Journal of Biogeography 43, 423–439 (2016).

Waldrop, E. et al. Phylogeography, population structure and evolution of coral‐eating butterflyfishes (Family Chaetodontidae, genus Chaetodon, subgenus Corallochaetodon). Journal of Biogeography 43, 1116–1129 (2016).

Coleman, R. R. et al. Regal phylogeography: Range-wide survey of the marine angelfish Pygoplites diacanthus reveals evolutionary partitions between the Red Sea, Indian Ocean, and Pacific Ocean. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 100, 243–253 (2016).

Randall, J. E. Reef and shore fishes of the Hawaiian Islands (University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 2007).

Bowen, B. W. et al. The origins of tropical marine biodiversity. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 28, 359–366 (2013).

Veron, J., Stafford-Smith, M., DeVantier, L. & Turak, E. Overview of distribution patterns of zooxanthellate Scleractinia. Frontiers in Marine Science 1, 81 (2015).

Obura, D. O. The diversity and biogeography of Western Indian Ocean reef-building corals. Plos One 7, e45013 (2012).

Obura, D. O. An Indian Ocean centre of origin revisited: Palaeogene and Neogene influences defining a biogeographic realm. Journal of Biogeography 43, 229–242 (2016).

Benzoni, F., Arrigoni, R., Stefani, F. & Stolarski, J. Systematics of the coral genus Craterastrea (Cnidaria, Anthozoa, Scleractinia) and description of a new family through combined morphological and molecular analyses. Systematics and Biodiversity 10, 417–433 (2012).

Arrigoni, R. et al. Forgotten in the taxonomic literature: resurrection of the scleractinian coral genus Sclerophyllia (Scleractinia, Lobophylliidae) from the Arabian Peninsula and its phylogenetic relationships. Systematics and Biodiversity 13, 140–163 (2015).

Terraneo, T. I. et al. Pachyseris inattesa sp. n. (Cnidaria, Anthozoa, Scleractinia): a new reef coral species from the Red Sea and its phylogenetic relationships. ZooKeys 433, 1–30 (2014).

Keshavmurthy, S. et al. DNA barcoding reveals the coral “laboratory-rat”, Stylophora pistillata encompasses multiple identities. Scientific Reports 3, 1520 (2013).

Stefani, F. et al. Comparison of morphological and genetic analyses reveals cryptic divergence and morphological plasticity in Stylophora (Cnidaria, Scleractinia). Coral Reefs 30, 1033–1049 (2011).

Richards, Z. T., Berry, O. & van Oppen, M. J. Cryptic genetic divergence within threatened species of Acropora coral from the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Conservation Genetics doi: 10.1007/s10592-015-0807-0 (2016).

Flot, J. F. et al. Incongruence between morphotypes and genetically delimited species in the coral genus Stylophora: phenotypic plasticity, morphological convergence, morphological stasis or interspecific hybridization? BMC Ecology 11, 22 (2011).

Arrigoni, R., Stefani, F., Pichon, M., Galli, P. & Benzoni, F. Molecular phylogeny of the robust clade (Faviidae, Mussidae, Merulinidae, and Pectiniidae): an Indian Ocean perspective. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 65, 183–193 (2012).

Scheer, G. & Pillai, C. G. Report on the stony corals from the Red Sea. Zoologica 45, 1–198 (1983).

Sheppard, C. R. C. & Sheppard, A. L. S. Corals and coral communities of Saudi Arabia. Fauna of Saudi Arabia 12, 1–170 (1991).

DiBattista, J. D. et al. On the origin of endemic species in the Red Sea. Journal of Biogeography 43, 13–40 (2016).

Ngugi, D. K., Antunes, A., Brune, A. & Stingl, U. Biogeography of pelagic bacterioplankton across an antagonistic temperature–salinity gradient in the Red Sea. Molecular Ecology 21, 388–405 (2012).

Hodge, J. R., van Herwerden, L. & Bellwood, D. R. Temporal evolution of coral reef fishes: global patterns and disparity in isolated locations. Journal of Biogeography 41, 2115–2127 (2014).

Ladner, J. T. & Palumbi, S. R. Extensive sympatry, cryptic diversity and introgression throughout the geographic distribution of two coral species complexes. Molecular Ecology 21, 2224–2238 (2012).

Rosser, N. L. Asynchronous spawning and demographic history shape genetic differentiation among populations of the hard coral Acropora tenuis in Western Australia. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 98, 89–96 (2016).

Schmidt-Roach, S. et al. Assessing hidden species diversity in the coral Pocillopora damicornis from Eastern Australia. Coral Reefs 32, 161–172 (2013).

Pinzon, J. H. & LaJeunesse, T. Species delimitation of common reef corals in the genus Pocillopora using nucleotide sequence phylogenies, population genetics and symbiosis ecology. Molecular Ecology 20, 311–325 (2011).

Warner, P. A., Oppen, M. J. & Willis, B. L. Unexpected cryptic species diversity in the widespread coral Seriatopora hystrix masks spatial‐genetic patterns of connectivity. Molecular Ecology 24, 2993–3008 (2015).

Todd, P. A. Morphological plasticity in scleractinian corals. Biological Reviews 83, 315–337 (2008).

Pfennig, D. W. et al. Phenotypic plasticity’s impacts on diversification and speciation. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 25, 459–467 (2010).

Veron, J. E. N. Corals of the world (Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, 2000).

Shaish, L., Abelson, A. & Rinkevich, B. How plastic can phenotypic plasticity be? The branching coral Stylophora pistillata as a model system. Plos One 2, e644 (2007).

Alamaru, A., Yam, R., Shemesh, A. & Loya, Y. Trophic biology of Stylophora pistillata larvae: evidence from stable isotope analysis. Marine Ecology Progress Series 383, 85–94 (2009).

Gattuso, J. P., Pichon, M. & Jaubert, J. Physiology and taxonomy of scleractinian corals: a case study in the genus Stylophora. Coral Reefs 9, 173–182 (1991).

Byler, K. A., Carmi-Veal, M., Fine, M. & Goulet, T. L. Multiple symbiont acquisition strategies as an adaptive mechanism in the coral Stylophora pistillata. Plos One 8, e59596 (2013).

Karako-Lampert, S. et al. Transcriptome analysis of the scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata. Plos One 7, e88615 (2014).

Klueter, A. & Andreakis, N. Assessing genetic diversity in the scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata (Esper 1797) from the Central Great Barrier Reef and the Coral Sea. Systematics and Biodiversity 11, 67–76 (2013).

Thornhill, D. J., Lewis, A. M., Wham, D. C. & LaJeunesse, T. C. Host-specialist lineages dominate the adaptive radiation of reef coral endosymbionts. Evolution 68, 352–367 (2013).

Sawall, Y., Al-Sofyani, A., Banguera-Hinestroza, E. & Voolstra, C. R. Spatio-temporal analyses of Symbiodinium physiology of the coral Pocillopora verrucosa along large-scale nutrient and temperature gradients in the Red Sea. Plos One 9, e103179 (2014).

LaJeunesse, T. C. & Thornhill, D. J. Improved resolution of reef-coral endosymbiont Symbiodinium species diversity, ecology, and evolution through psbA non-coding region genotyping. Plos One 6, e29013 (2011).

Flot, J. F., Tillier, A., Samadi, S. & Tillier, S. Phase determination from direct sequencing of length‐variable DNA regions. Molecular Ecology Notes 6, 627–630 (2006).

Budd, A. Diversity and extinction in the Cenozoic history of Caribbean reefs. Coral Reefs 19, 25–35 (2000).

Baron-Szabo, R. C. Corals of the K/T-boundary: Scleractinian corals of the suborders Astrocoeniina, Faviina, Rhipidogyrina and Amphiastraeina. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 4, 1–108 (2006).

Antunes, A. & Ramos, M. J. Discovery of a large number of previously unrecognized mitochondrial pseudogenes in fish genomes. Genomics 86, 708–717 (2005).

Wei, N. W. V., Wallace, C. C., Dai, C. F., Moothien Pillay, K. R. & Chen, C. A. Analyses of the ribosomal internal transcribed spacers (ITS) and the 5.8S gene indicate that extremely high rDNA heterogeneity is a unique feature in the scleractinian coral genus Acropora (Scleractinia; Acroporidae). Zoological Studies 45, 404–418 (2006).

Taviani, M. Post-Miocene reef faunas of the Red Sea: glacio-eustatic controls in Sedimentation and tectonics in rift basins: Red Sea-Gulf of Aden (eds. Purser, B. H. et al.) Ch. 13, 574–582 (Chapman and Hall, London, 1998).

Marti-Puig, P. et al. Extreme phenotypic polymorphism in the coral genus Pocillopora; micro-morphology corresponds to mitochondrial groups, while colony morphology does not. Bulletin of Marine Science 90, 211–231 (2014).

Miller, K. J. & Ayre, D. J. The role of sexual and asexual reproduction in structuring high latitude populations of the reef coral Pocillopora damicornis. Heredity 92, 557–568 (2004).

Frade, P. R., et al. Semi-permeable species boundaries in the coral genus Madracis: introgression in a brooding coral system. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 57, 1072–1090 (2010).

Combosch, D. J. & Vollmer, S. V. Trans-Pacific RAD-Seq population genomics confirms introgressive hybridization in Eastern Pacific Pocillopora corals. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 88, 154–162 (2015).

Willis, B. L., van Oppen, M. J., Miller, D. J., Vollmer, S. V. & Ayre, D. J. The role of hybridization in the evolution of reef corals. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 37, 489–517 (2006).

Richards, Z. T. & Hobbs, J. P. A. Hybridisation on coral reefs and the conservation of evolutionary novelty. Current Zoology 61, 132–145 (2015).

Rueffler, C., Van Dooren, T. J., Leimar, O. & Abrams, P. A. Disruptive selection and then what? Trends in Ecology and Evolution 21, 238–245 (2006).

LaJeunesse, T. C. et al. Long‐standing environmental conditions, geographic isolation and host–symbiont specificity influence the relative ecological dominance and genetic diversification of coral endosymbionts in the genus Symbiodinium. Journal of Biogeography 37, 785–800 (2010).

Sampayo, E. M., Franceschinis, L., Hoegh-Guldberg, O. & Dove, S. Niche partitioning of closely related symbiotic dinoflagellates. Molecular Ecology 16, 3721–3733 (2007).

Bongaerts, P. et al. Sharing the slope: depth partitioning of agariciid corals and associated Symbiodinium across shallow and mesophotic habitats (2–60 m) on a Caribbean reef. BMC Evolutionary Biology 13, 205 (2013).

Arif, C. et al. Assessing Symbiodinium diversity in scleractinian corals via next‐generation sequencing‐based genotyping of the ITS2 rDNA region. Molecular Ecology 23, 4418–4433 (2014).

Huang, D., Meier, R., Todd, P. A. & Chou, L. M. Slow mitochondrial COI sequence evolution at the base of the metazoan tree and its implications for DNA barcoding. Journal of Molecular Evolution 66, 167–174 (2008).

Vollmer, S. V. & Palumbi, S. R. Testing the utility of internally transcribed spacer sequences in coral phylogenetics. Molecular Ecology 13, 2763–2772 (2004).

Pante, E. et al. Use of RAD sequencing for delimiting species. Heredity 114, 450–459 (2015).

Flot, J. F. SeqPHASE: a web tool for interconverting PHASE input/output files and FASTA sequence alignments. Molecular Ecology Resources 10, 162–166 (2010).

Stephens, M., Smith, N. J. & Donnelly, P. A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from population data. The American Journal of Human Genetics 68, 978–989 (2001).

Flot, J. F. Champuru 1.0: a computer software for unraveling mixtures of two DNA sequences of unequal lengths. Molecular Ecology Notes 7, 974–977 (2007).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30, 772–780 (2013).

Martin, D. P. et al. RDP3: a flexible and fast computer program for analyzing recombination. Bioinformatics 26, 2462–2463 (2010).

Librado, P. & Rozas, J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 25, 1451–1452 (2009).

Darriba, D., Taboada, G. L., Doallo, R. & Posada, D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nature Methods 9, 772–772 (2012).

Ronquist, F. et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Systematic Biology 61, 539–542 (2012).

Rambaut, A., Suchard, M. A., Xie, D. & Drummond, A. J. Tracer v1.6 http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/Tracer/ (2014).

Guindon, S. & Gascuel, O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Systematic Biology 52, 696–704 (2003).

Swofford, D. L. PAUP. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (and other methods). Version 4 (Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts, 2003).

Bandelt, H. J., Forster, P. & Röhl, A. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution 16, 37–48 (1999).

Flot, J. F., Couloux, A. & Tillier, S. Haplowebs as a graphical tool for delimiting species: a revival of Doyle’s. BMC Evolutionary Biology 10, 372 (2010).

Excoffier, L. & Lischer, H. E. L. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Molecular Ecology Resources 10, 564–567 (2010).

Drummond, A. J., Suchard, M. A., Xie, D. & Rambaut, A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Molecular Biology and Evolution 29, 1969–1973 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the captain and crew of the MV Dream-Master, AK Gusti (KAUST), and the KAUST Coastal and Marine Resources Core Lab for fieldwork logistics in the Red Sea. Grazie to Tane H Sinclair-Taylor (KAUST) for graphic assistance. RA and TIT gratefully acknowledge P Saenz-Agudelo (UACH) and JD DiBattista (CURTIN) for their first assistance at KAUST. WE thank the two anonymous reviewers for their comments to earlier versions of the manuscript. This project was supported by funding from KAUST (award # URF/1/1389-01-01, FCC/1/1973-07, and baseline research funds to ML Berumen). This research was undertaken in accordance with the policies and procedures of the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST). Permissions relevant for KAUST to undertake the research have been obtained from the applicable governmental agencies in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.A., F.B. and M.L.B. designed the research. F.B., T.I.T. and A.C. collected samples. R.A., T.I.T. and A.C. performed molecular work. R.A. analysed data. R.A. and M.L.B. wrote the paper with revisions contributed by all authors.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Arrigoni, R., Benzoni, F., Terraneo, T. et al. Recent origin and semi-permeable species boundaries in the scleractinian coral genus Stylophora from the Red Sea. Sci Rep 6, 34612 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep34612

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep34612

This article is cited by

-

Shallow and mesophotic colonies of the coral Stylophora pistillata share similar regulatory strategies of photosynthetic electron transport but differ in their sensitivity to light

Coral Reefs (2023)

-

Coral microbiome composition along the northern Red Sea suggests high plasticity of bacterial and specificity of endosymbiotic dinoflagellate communities

Microbiome (2020)

-

Towards a rigorous species delimitation framework for scleractinian corals based on RAD sequencing: the case study of Leptastrea from the Indo-Pacific

Coral Reefs (2020)

-

Incongruence between life-history traits and conservation status in reef corals

Coral Reefs (2020)

-

A genomic glance through the fog of plasticity and diversification in Pocillopora

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.