Abstract

The practical use of solid-state nanopores for DNA sequencing requires easy fabrication of the nanopores, reduction of the DNA movement speed and reduction of the ionic current noise. Here, we report an integrated nanopore platform with a nanobead structure that decelerates DNA movement and an insulating polyimide layer that reduces noise. To enable rapid nanopore fabrication, we introduced a controlled dielectric breakdown (CDB) process into our system. DNA translocation experiments revealed that single nanopores were created by the CDB process without sacrificing performance in reducing DNA movement speed by up to 10 μs/base or reducing noise up to 600 pArms at 1 MHz. Our platform provides the essential components for proceeding to the next step in the process of DNA sequencing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Single-molecule detection is vital for basic research and practical applications in nanobiotechnology and nanomedicine1. Nanopore sensors are a promising technology for label-free single-molecule detection2. Nanopore technology is particularly attractive for DNA sequencing because of its potential advantages, which include long reads, low cost and high speed3,4,5. These promising advantages have driven the dramatic developments in practical nanopore DNA sequencing6,7.

Depending on their composition, nanopores are categorized as biological8,9,10,11,12 or solid-state2,13,14. Although significant advances towards practical sequencing have been accomplished by utilizing biological nanopores, solid-state nanopores are more promising because of their robustness and the stability of their materials. For example, biological nanopores offer low noise performance, but the fragility of the lipid bilayer membrane limits the device lifetime and the applied voltage, which contributes to the signal-to-noise ratio. By contrast, solid-state nanopores are robust under various experimental conditions, such as high applied voltage, pH and temperature15,16.

A bottleneck in achieving solid-state nanopore sequencing is the ultrafast translocation of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) through the nanopore17 even when utilizing a newly developed rapid amplifier (1 MHz sampling rate)18. This rapid translocation prevents the collection of sufficient current data per base. To obtain more than 10 data points per base, the speed should typically be slower than 10 μs/base. Various methods have been explored in pursuit of decelerating the passage of DNA: (i) narrowing the nanopore diameter19,20, (ii) increasing the solution viscosity21,22, (iii) decreasing the temperature15,23, (iv) neutralizing the negative charge of the DNA using alternate salts (LiCl solution)24. Although several groups succeeded in deceleration of DNA translocation utilizing graphene25,26,27,28 or HfO229 nanopore, from a practical point of view, silicon nitride (SiN) nanopore are more suitable for mass-production. Despite these tremendous efforts, the deceleration of the translocation speed remains insufficient for sequencing DNA based on a solid-state nanopore (especially SiN nanopores). Moreover, these methods typically alter the ionic environment around the nanopore, which often leads to smaller ionic currents and decreases the signal-to-noise ratio.

In the past three years, several research groups have successfully developed a new method involving the use of nanometre-sized 3D structures, including nanofibre meshes30, gel meshes31,32 and bead structures33, to decelerate DNA translocation. These methods are simple yet effective in slowing the passage of DNA without sacrificing the signal-to-noise ratio. We recently demonstrated that a nanometre-sized bead structure around a nanopore can decelerate DNA translocation by up to 10 μs/base33 even for ssDNA, the translocation speed of which is 100-fold faster than that of double-stranded DNA20. Although our approach has potential for realizing DNA sequencing with a solid-state nanopore, some technical challenges remain. For example, in a proof-of-concept experiment, a nanopore has been fabricated using a transmission electron microscope (TEM) beam before providing the 3D structure on the membrane. However, from a practical perspective, TEM-based nanopore fabrication faces the following issues: (i) TEM-based fabrication is not suitable for mass-production because it is time-consuming and laborious; and (ii) although the nanopore should be fabricated after providing the 3D structure for long-term storage of a device, a nanopore cannot be intrinsically fabricated by a TEM beam because the beam cannot reach the membrane due to electron-beam scattering of the structure. Therefore, an alternative nanopore fabrication method is required that is compatible with the 3D structure needed to decelerate DNA translocation.

Alternative fabrication methods utilizing controlled dielectric breakdown (CDB) have recently been proposed and demonstrated16,34,35,36. Voltage-induced dielectric breakdown events in ultrathin membranes result in the formation of single nanopores with diameters as small as 1 nm. Additionally, CDB can precisely fabricate nanopores with sub-nanometre accuracy under the appropriate conditions37. Because CDB is typically based on the voltage injection process, unless the ionic behaviour is inhibited, fabrication processes based on CDB are expected to be compatible with DNA-speed-decelerating structures such as beads. Waugh et al. reported that nanopores can be fabricated via dielectric breakdown even after coating a gel mesh on the membrane31. Similarly, we expected that single nanopores could be fabricated via dielectric breakdown even after coating of a bead structure on the membrane. We recently reported a new CDB process termed “multilevel pulse-voltage injection (MPVI)”35. Compared with the conventional CDB process, MPVI is less damaging because it utilizes pulse-voltages to create and widen the nanopore and nanopore generation is verified at every pulse interval by measuring the current at low voltage. In the present report, we introduce a fabrication process based on MPVI to our bead-coating device to address both nanopore fabrication and deceleration of the DNA speed.

In addition to the above challenges, a nanopore system requires the reduction of the ionic current noise to improve the signal-to-noise ratio, particularly in the high-frequency range (e.g., 1 MHz). The device capacitance arising from the surface area exposed to the solution dominates the high-frequency noise38. To decrease the surface area of the device, an insulating layer (e.g., poly(dimethylsiloxane) or polyimide) was also integrated into our device. In the present work, we demonstrate that dielectric breakdown induced by an applied pulse-voltage can produce a single nanopore on a membrane after coating with 50-nm nanobeads while maintaining structure. We also confirm that the deceleration of ssDNA translocation is retained following MPVI-based nanopore fabrication. Furthermore, we investigated whether an insulating layer, i.e., polyimide, coated on the device simultaneously with the nanobead structure can reduce the ionic current noise.

Results and Discussion

Single nanopore fabrication via MPVI

First, we investigated the effect of the nanobead structure on the MPVI nanopore fabrication process. Waugh et al. reported that the gel media interface with the membrane does not prevent the dielectric breakdown process owing to the availability of ions for charge injection31. Similarly, we expected that the nanobead structure would have no effect on the dielectric breakdown nanopore fabrication process because the resistance of the structure can be ignored relative to that of the nanopore33 (Fig. 1). The behaviour of the device in DNA-decelerating media during fabrication has yet to be reported in detail, particularly in terms of whether the fabricated nanopore is truly single. Actually, when the breakdown condition is not optimized, MPVI process fails to fabricate a single nanopore (see Supplementary Figures S1 and S2). In general, single nanopore fabrication is verified by direct TEM observation. However, the DNA-decelerating structure hinders the direct observation of the nanopore on the membrane (see Supplementary Figure S3). Accordingly, prior to assessing the performance, we focused on the verification of the creation of a single nanopore by MPVI.

Schematic of nanopore fabrication via dielectric breakdown of an ultrathin SiN membrane with a nanometre-sized bead structure.

(a) The electrolytes can move freely through the spaces between the nanobeads, providing ion access to the membrane. (b) Upon application of a trans-membrane voltage over the breakdown value to the membrane, dielectric breakdown occurred in the membrane. Because the breakdown event occurred only in the membrane, a nanopore was generated without deforming the nanobead structure.

Figure 2 provides a schematic diagram of the solid-state device with a layer of nanometre-sized beads on the SiN membrane from the cis side. The solid-state substrate for nanopore fabrication (see Supplementary Figure S4), the bead layer and the polyimide layer were prepared as previously reported33,35,38. Nanopore fabrication via the MPVI procedure was performed in situ under typical conditions (1 M KCl aqueous solution with Tris-EDTA buffer, 10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5). A pulse-voltage from 9 V to 10 V was applied to the membrane for a maximum cumulative time of 1 s. The leakage current across the membrane at 0.1 V was monitored at every interval of the pulse. Figure 3 illustrates the leakage currents of a non-coated device (bare, blue), a polyimide-coated device (red) and a bead-polyimide-coated device (green) after the induction of a pulse-voltage. In all cases, similar dependences of the currents at a voltage of 0.1 V on the cumulative applied pulse durations were observed. After continuing feeble leakage currents through the membrane, sudden increases in the leakage currents occurred with all devices and exceeded a pre-defined threshold (10 pA, i.e., the same as the previous report35). This abrupt increase in the current is evidence of a typical dielectric breakdown and implies the generation of a nanopore35. Importantly, the breakdown voltages of the polyimide-coated devices and the bead-polyimide-coated devices (9.4 ± 0.4 V, N = 9) were nearly identical to those of bare devices (9.6 ± 0.4 V, N = 9), thus indicating that the polyimide and bead layers had no effect on the dielectric breakdown process. This behaviour is consistent with the negligible ionic resistance of the bead coating layer relative to that of the nanopore33 and indicates that the bead structure does not prevent the ionic path through the membrane.

Schematic diagram of a substrate with nanobead structure and insulating layer used for nanopore fabrication via controlled dielectric breakdown.

A 100-nm-thick Si3N4 layer, 250-nm-thick SiO2 layer and 10-nm Si3N4 layer were deposited on the Si substrate. A square hole (500 × 500 nm2) was fabricated by dry etching and the SiO2 layer was partially eliminated by HF etching. The bead layer was first coated over the entire surface at both sides of the substrate via the dip-coating method and polyimide was subsequently coated on the substrate as an insulating layer.

Further investigation is required to confirm the generation of a single nanopore by MPVI. The diameter of a single nanopore can be estimated from its current at a predefined applied voltage. After optimization of parameters, we confirmed that nanopore variation was quite small and MPVI process can fabricate precisely and reproducibly nanopores with sub-nanometre accuracy (see Supplementary Table S1). We examined whether the generated nanopore was indeed single by conducting ssDNA translocation experiments. Figure 4a presents typical ionic current traces for the open-state and state blocked by DNA (blocked-state) without clogging the nanopore. For a baseline ionic current of 1.2 nA at 0.3 V, the predicted diameter of a single nanopore is 1.4 nm. The full blockade phenomenon occurs when ssDNA translocates across a nanopore with a diameter of less than 1.4 nm19. Therefore, the mean blockade current of the ssDNA was expected to be 1.2 nA. As illustrated in Fig. 4b (blockade current histogram), the drop-down magnitude was 1.2 ± 0.05 nA and exactly equal to the open-state current level, strongly indicating that MPVI generated only a single nanopore even after polyimide and bead coating. The results also indicated that the blockade current level was not affected by the bead layer or the MPVI process.

ssDNA blocking events through a nanopore fabricated via the MPVI process.

(a) A typical time trace of the ionic current for a nanopore created via MPVI on a bead-polyimide-coated device. Blockade events for the 60-mer single-stranded poly(dA) were detected in 1 M KCl aqueous solution at 0.3 V (low-pass filtered at 100 kHz). (b) Normalized histogram of the blockade currents for a 60-mer single-stranded poly(dA) using the same data depicted in (a).

After the nanopore generation and ssDNA translocation experiments, the surface condition of the device was confirmed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) as depicted in Fig. 5. The membrane area is indicated by the dashed line. The SEM observations revealed that the close-packed bead structure was maintained without cracks even after pulse-voltage injection and DNA translocation. This closely packed state contributes to a stable nanostructure that prevents the beads from re-dispersing into the solution. Based on this observation, the maintained bead structure was expected to decrease the DNA movement speed. Overall, these results indicate that the MPVI process is suitable for nanopore fabrication on devices with nanobead structures.

Performance in decelerating DNA movement and reducing noise

The ability to control ssDNA movement speed through an MPVI-fabricated nanopore with beads was assessed with DNA translocation experiments using 60-mer single-stranded poly(dA). We previously reported that the nanosized bead structure decelerates DNA translocation by up to 10 μs/base even when using short 60-mer ssDNA33. Here, we investigated whether the duration of residence of ssDNA in the MPVI-fabricated nanopore with beads was identical to that in a TEM-fabricated nanopore with beads. A comparison of the durations of the two series is displayed in log-scaled histograms in Fig. 6a. These histograms are clearly similar and well fit by an identical log-normal distribution. Quantitatively, the peak dwell times of the DNA translocation through the MPVI-fabricated nanopore and the TEM-fabricated nanopore were both 16 μs/base, consistent with previously reported results33.

Histograms of the dwell times for ssDNA translocation.

(a) Log-scaled histograms of the dwell times for a TEM-fabricated nanopore with beads (orange, N = 1319) and a MPVI-fabricated nanopore with beads (green, N = 1323). ssDNA (60-mer single-stranded poly(dA)) translocation was measured in 1 M KCl solution. The applied voltage was 0.3 V (low-pass filtered at 5 kHz). The nanopore diameters were 3.0 nm (orange) and 3.7 nm (green). (b) Log-scaled histogram of the dwell times of a bead-coated substrate (red, N = 1246) and a bead-polyimide-coated substrate (blue, N = 1712). Single nanopores in each device were fabricated via the MPVI process. Poly(dA33dC33dA33) was used as a ssDNA sample. The applied voltage was 0.3 V (filtered at 100 kHz). The dashed lines are curves that were fit to the log-normal distributions. The nanopore diameters were 3.4 nm (red) and 2.2 nm (blue).

Although we used nanopores with different diameters in the translocation experiments, we consider that the effect of the nanopore size on translocation speed is negligible in the system using beads. Several researches has already reported that DNA translocation speed without any slowing-down media, such as gel or beads, depends on the diameters of SiN nanopores13,20,39. Especially, translocation speed of ssDNA ranged from <0.01 μs/base (3.0 − 4.0 nm) to 0.3 μs/base (1.4 − 2.0 nm)13,20,33. To investigate data reliability, we conducted the translocation experiment of the same 60-mer ssDNA through a nanopore without beads (see Supplementary Figure S5). Expectedly, we confirmed that translocation speed of 60-mer ssDNA was 0.3 μs/base (2.2 nm), which is consistent with the previous reported values13,20,33. Therefore, if the bead layer has no effect on slowing down of DNA translocation speed, the calculated dwell times of 60-mer ssDNA would be shorter than 18 μs in the experiments using bead-coated SiN nanopores with diameters from 2.3 nm to 3.7 nm. However, as shown in Fig. 6, the characteristic dwell times of SiN nanopores with beads were at least approximately 1000 μs, which are much longer than the calculated values. These results indicate that the DNA translocation process is not dominated by the interaction at the nanopore sidewall20,39 but governed by the interaction at the nanobead layer. This comparative study strongly supports that the nanobead layer can decelerate the DNA translocation speed even when integrating MPVI process.

Given that the interaction at the nanobead layer governs the translocation process, it is expected that the translocation speed of ssDNA with beads is independent on the diameters of nanopores. To verify this tendency, we conducted the translocation experiments using the several diameters of SiN nanopores with beads (see Supplementary Figures S6 and S7). Figure S7 clearly shows that translocation speed when using the substrate with beads was almost independent on the diameters of SiN nanopores (from 1.6 nm to 3.7 nm) and the average speed was 16 μs/base, while the speed using the uncoated substrate strongly depends on20. The results also support that ssDNA translocation is decelerated by the bead layer.

Accordingly, these results indicate that the deceleration of DNA translocation by the nanobead structure was maintained following the MPVI process and strongly suggests that nanopore fabrication via the MPVI process did not degrade the nanobead structure, in agreement with the SEM observations presented in Fig. 5. Figure 6b presents duration histograms for a bead-coated device (no polyimide) and a bead-polyimide-coated device based on DNA translocation experiments conducted with single-stranded poly(dA33dC33dA33). The polyimide layer would not be expected to affect the DNA translocation speed because it is located far from the nanopore membrane. As expected, the two histograms were nearly identical and were similarly well fitted by identical log-normal distributions, with a peak dwell time of 22 μs/base. Notably, the observed DNA speed is appropriate for collecting more than 10 data points per base.

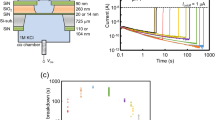

To further characterize the performance, power spectral density plots (PSD) of the ionic current were created for the nanopores fabricated in each device. Figure 7a presents the PSD curve of each device and these curves clearly depict the reduced noise spectra of the polyimide device and the bead-polyimide device across the entire frequency regime. The device capacitance arising from the surface area exposed to the electrolyte solution governs the typical ionic current noise at high frequency38. The noise arising from the device capacitance was calculated to be 1000 pF for the bare device and 50 pF for the polyimide-coated device and bead-polyimide-coated device. The PSD spectrum of the polyimide-coated device remained nearly unchanged following coating of the bead layer. The typical current noise was highlighted by the baseline current trace of each device during the application of no voltage as illustrated in Fig. 7b. The RMS noise at 1 MHz was 580 pArms for the polyimide-coated device and 620 pArms for the bead polyimide-coated device, which represent 2.5-fold reductions (1500 pArms for the bare device). These results are consistent with previous findings that the bead layer does not affect the I-V characteristics or noise performance33.

Noise characteristics of the various devices.

(a) Current power spectral densities (PSD) of the nanopores on a bare substrate (blue), a polyimide-coated device (red) and a bead-polyimide-coated device (green). The diameters of the nanopores on each device ranged from 1 nm to 3 nm. (b) Typical baseline ionic current noise traces corresponding to the PSD curves described in (a). The ionic current noise was measured at 0 V in 1 M KCl aqueous solution using a 1-MHz high-speed amplifier VC100. The detected currents were low-pass filtered with a cut-off frequency of 1 MHz.

Conclusion

In summary, we have demonstrated that a single nanopore can be fabricated by the MPVI process even after coating a bead layer on the membrane. The control of the DNA translocation speed by the nanobead structure was maintained following MPVI nanopore creation. The duration of ssDNA translocation across the nanopore was decelerated by up to 10–20 μs/base, thus improving the temporal resolution of single-molecule detection. Simultaneously, the noise arising from the device capacitance was reduced by the polyimide layer. Our approach is compatible with solid-state platforms because the bead layer, polyimide layer and MPVI process did not affect performance in terms of noise, I-V characteristics, single nanopore creation or deceleration of DNA translocation. We believe that our platform will be a key component in DNA sequencing based on solid-state nanopores.

Methods

The bead coating and nanopore fabrication device

Substrates with 10-nm-thick Si3N4 membranes and small square areas of 500 × 500 nm2 were prepared (see Supplementary Figure S4) as previously reported35. The motion of the coated beads was confined to this square, which stabilized the bead structures. The bead coating was applied to the substrate by dip coating as previously reported33. Before the dip coating, the substrates were cleaned and hydrophilized on each side with argon/oxygen plasma (PA-1, SAMCO, Kyoto, Japan) at 10 W, a flow rate of 20 sccm and a pressure of 20 Pa for 45 s. The substrates were dipped into an aqueous silica-bead solution (50-nm amine-functionalized silica beads, Micromod, Rostock, Germany) and removed at a speed of approximately 1 mm/s. After removal from the solution, the substrates were dried in an oven (DO-300PA, AS ONE, Osaka, Japan) at 120 °C for 10 minutes. The insulating polymer, i.e., polyimide, was coated on the substrate after bead coating at a thickness of 5–10 μm by spreading out a drop of polyimide under a stereoscopic microscope. The coated polyimide was cured in a thermostat chamber for 30 min at 110 °C and 30 min at 300 °C. Prior to beginning the MPVI procedure, the device was cleaned and re-hydrophilized on each side with argon/oxygen plasma at a flow rate of 20 sccm, a pressure of 20 Pa and a power of 10 W for 45 s. The bead coating condition was confirmed by SEM (S-5200, Hitachi High-Technologies, Ibaraki, Japan) at 5 kV after the MPVI procedure and ssDNA translocation experiments.

Nanopore fabrication by the MPVI process

MPVI was performed as follows. Two chambers (cis and trans chambers) were formed in a custom flow cell. We recently determined that an electric charge difference between the chambers generates defects in the membrane, particularly when the capacitance of the substrate is less than 100 pF38. To prevent initial defects, the charge difference was neutralized using an electric bypass channel connected to both chambers. Both chambers were filled with 1 M KCl aqueous solution (pH 7.5) buffered with 10 mM Tris and 1 mM EDTA. Two Ag/AgCl electrodes (cis and trans electrodes) were immersed in the solutions and connected to a pulse-voltage generator (41501B SMU and pulse generator expander, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and an ammeter (4156B Precision semiconductor analyser, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA. The MPVI procedure was controlled by a program written using Excel Visual Basic for Applications (VBA). The applied voltage and pulse duration were optimized to fabricate a nanopore with the desired diameter. The diameter of the MPVI-fabricated nanopore was calculated using equation (1).

Here, Inp is the ionic current through the nanopore, V is the applied voltage across the membrane, σ is the conductivity of the solution (the measured value was approximately 10.8 S/m), ϕm is the diameter of the nanopore and heff is the effective thickness of the membrane. We previously reported that the heff of a 10-nm-thick Si3N4 membrane is 3.7 nm33. Accordingly, we estimated the diameter of the nanopore from the relationship between Inp and ϕm at V = 0.1 V.

ssDNA blockade current measurements

The prepared substrates were assembled in the same flow cell used for the MPVI method. Two chambers (a cis chamber and a trans chamber, each with a volume of 90 μL) separated by the substrate were formed in the flow cell. Both chambers were filled with an aqueous solution consisting of 1 M KCl (pH 7.5) buffered with 10 mM Tris and 1 mM EDTA. Poly(dA60) and poly(dA33dC33dA33) purchased from Nihon Gene Research Laboratory (Miyagi, Japan) were used as model ssDNA molecules. Only the solution in the cis chamber contained single-stranded DNA at a concentration 50 nM. An Ag/AgCl electrode was immersed in each solution to ensure electrical contact between the chambers.

To detect the ssDNA translocation events, we conducted experiments with a low-noise voltage-clamp amplifier (VC100, Chimera Instruments, New York, NY, USA). The ionic current was measured at an applied voltage of 0.3 V. The acquired data were digitally low-pass filtered at 100 kHz. Current blockade events were identified and analysed using the open-source software package OpenNanopore40.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Goto, Y. et al. Integrated solid-state nanopore platform for nanopore fabrication via dielectric breakdown, DNA-speed deceleration and noise reduction. Sci. Rep. 6, 31324; doi: 10.1038/srep31324 (2016).

References

Bayley, H. & Martin, C. R. Resistive-pulse sensing –from microbes to molecules. Chem. Rev. 100, 2575–2594 (2000).

Dekker, C. Solid-state nanopores. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2, 209–215 (2007).

Branton, D. et al. The potential and challenges of nanopore sequencing. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1146–1153 (2008).

Metzker, M. L. Sequencing technologies - the next generation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 31–46 (2010).

Venkatesan, B. M. & Bashir, R. Nanopore sensors for nucleic acid analysis. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 615–624 (2011).

Jain, M. et al. Improved data analysis for the MinION nanopore sequencer. Nat. Methods. 12, 351–356 (2015).

Szalay, T. & Golovchenko, J. A. De novo sequencing and variant calling with nanopores using PoreSeq. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 1087–1091 (2015).

Manrao, E. A. et al. Reading DNA at single-nucleotide resolution with a mutant MspA nanopore and phi29 DNA polymerase. Nature Biotechnol. 30, 349–353 (2012).

Ayub, M. & Bayley, H. Individual RNA base recognition in immobilized oligonucleotides using a protein nanopore. Nano lett. 12, 5637–5643 (2012).

Cherf, G. M. et al. Automated forward and reverse ratcheting of DNA in a nanopore at 5-Å precision. Nature Biotechnol. 30, 344–348 (2012).

Laszlo, A. H. et al. Decoding long nanopore sequencing reads of natural DNA. Nature Biotechnol. 32, 829–833 (2014).

Laszlo, A. H. et al. Detection and mapping of 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine with nanopore MspA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 18904–18909 (2013).

Venta, K. et al. Differentiation of short, single-stranded DNA homopolymers in solid-state nanopores. ACS Nano 7, 4629–4636 (2013)

Xie, P., Xiong, Q., Fang, Y., Qing, Q. & Lieber, C. M. Local electrical potential detection of DNA by nanowire–nanopore sensors. Nature Nanotechnol. 7, 119–125 (2012).

Verschueren, D. V., Jonsson, M. P. & Dekker, C. Temperature dependence of DNA translocations through solid-state nanopore. Nanotechnology 26, 234004 (2015).

Briggs, K. et al. Kinetics of nanopore fabrication during controlled breakdown of dielectric membrane in solution. Nanotechnology 26, 084004 (2015).

Wanunu, M. Nanopores : A journey towards DNA sequencing. Phys. Life. Rev. 9, 125–158 (2012).

Rosenstein, J. K., Wanunu, M., Merchant, C. A., Drndic, M. & Shepard, K. L. Integrated nanopore sensing platform with sub-microsecond temporal resolution. Nature Methods 9, 487–492 (2012).

Mirsaidov, U., Comer, J., Dimitrov, V., Aksimentiev, A. & Timp, G. Slowing the translocation of double-stranded DNA using a nanopore smaller than the double helix. Nanotechnology 21, 395501 (2010).

Akahori, R. et al. Slowing single-stranded DNA translocation through a solid-state nanopore by decreasing the nanopore diameter. Nanotechnology 25, 275501 (2014).

Fologea, D., Uplinger, J., Thomas, B., McNabb, D. S. & Li, J. Slowing DNA translocation in a solid-state nanopore. Nano Lett. 5, 1734–1737 (2005).

Singer, A., Kuhn, H., Frank-Kamenetskii, M. & Meller, A. Detection of urea-induced internal denaturation of dsDNA using solid-state nanopores. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 22, 454111 (2010).

Meller, A., Nivon, L., Brandin, E., Golovchenko, J. & Branton, D. Rapid nanopore discrimination between single polynucleotide molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.USA 97, 1079–1084 (2000).

Kowalczyk, S. W., Wells, D. B., Aksimentiev, A. & Dekker, C. Slowing down DNA Translocation through a Nanopore in Lithium Chloride. Nano. Lett. 12, 1038–1044 (2012).

Merchant, C. A. et al. DNA translocation through graphene nanopores. Nano Lett. 10, 2915–2921 (2010).

Schneider, G. F. et al. DNA translocation through graphene nanopores. Nano Lett. 10, 3163–3167 (2010).

Freedman, K. J., Ahn, C. W. & Kim, M. J. Detection of long and short DNA using nanopores with graphitic polyhedral edges. ACS Nano 7, 5008–5016 (2013).

Banerjee, S. et al. Slowing DNA transport using graphene-DNA interactions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 936–946 (2015).

Larkin, J. et al. Slow DNA transport through nanopores in hafnium oxide membranes. ACS Nano 7, 10121–10128 (2013).

Squires, A. H., Hersey, J. S., Grinstaff, M. W. & Meller, A. A nanopore–nanofiber mesh biosensor to control DNA translocation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 16304–16307 (2013).

Waugh, M. et al. Interfacing solid-state nanopores with gel media to slow DNA translocations. Electrophoresis 36, 1759–1767 (2015).

Tang, Z. et al. Gel mesh as “brake” to slow down DNA translocation through solid-state nanopores. Nanoscale 7, 13207–13214 (2015).

Goto, Y., Haga, T., Yanagi, I., Yokoi, T. & Takeda, K. Deceleration of single-stranded DNA passing through a nanopore using a nanometre-sized bead structure. Sci. Rep. 5, 16640 (2015).

Kwok, H., Briggs, K. & Tabard-Cossa, V. Nanopore Fabrication by Controlled Dielectric Breakdown. PLos One 9, e92880 (2014).

Yanagi, I., Akahori, R., Hatano, T. & Takeda, K. Fabricating nanopores with diameters of sub-1 nm to 3 nm using multilevel pulse-voltage injection. Sci. Rep. 4, 5000 (2014).

Tahvildari, R., Beamish, E., Tabard-Cossa, V. & Godin, M. Integrating nanopore sensors within microfluidic channel arrays using controlled breakdown. Lab on a Chip, 15, 1407–1411 (2015).

Briggs, K., Kwok, H. & Tabard-Cossa, V. Automated fabrication of 2-nm solid-state nanopores for nucleic acid analysis. Small 10, 2077–2086 (2014).

Matsui, K., Yanagi, I., Goto, Y. & Takeda, K. Prevention of dielectric breakdown of nanopore membranes by charge neutralization. Sci. Rep. 5, 17819 (2015).

Wanunu, M., Sutin, J., McNally, B., Chow, A. & Meller, A. DNA translocation governed by interactions with solid-state nanopores. Biophys. J. 95, 4716–4725 (2008).

Raillon, C. P. et al. Fast and automatic processing of multilevel events in nanopore translocation experiments. Nanoscale 4, 4916–4924 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Rena Akahori, Dr. Takashi Anazawa, Dr. Naoshi Itabashi and Dr. Asako Koike of Hitachi for valuable discussions and critical comments on the manuscript. We are also grateful to Mr. Yoshikazu Nara for customizing the analysis software.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.G. performed the experiments and analysed the data. I.Y. prepared the substrate for nanopore fabrication. K.M. designed the flow cell for preventing the initial defect. T.Y. synthesized the ssDNA. K.T. supervised the study.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Goto, Y., Yanagi, I., Matsui, K. et al. Integrated solid-state nanopore platform for nanopore fabrication via dielectric breakdown, DNA-speed deceleration and noise reduction. Sci Rep 6, 31324 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep31324

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep31324

This article is cited by

-

Solid-state nanopores towards single-molecule DNA sequencing

Journal of Human Genetics (2020)

-

Low-frequency noise induced by cation exchange fluctuation on the wall of silicon nitride nanopore

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Stable fabrication of a large nanopore by controlled dielectric breakdown in a high-pH solution for the detection of various-sized molecules

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Two-step breakdown of a SiN membrane for nanopore fabrication: Formation of thin portion and penetration

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Surveying silicon nitride nanopores for glycomics and heparin quality assurance

Nature Communications (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.