Abstract

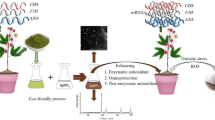

It is well known that graphene (G) induces nanotoxicity towards living organisms. Here, a novel and biocompatible hydrated graphene ribbon (HGR) unexpectedly promoted aged (two years) seed germination. HGR formed at the normal temperature and pressure (120 days hydration), presented 17.1% oxygen, 0.9% nitrogen groups, disorder-layer structure, with 0.38 nm thickness ribbon morphology. Interestingly, there were bulges around the edges of HGR. Compared to G and graphene oxide (GO), HGR increased seed germination by 15% root differentiation between 52 and 59% and enhanced resistance to oxidative stress. The metabonomics analysis discovered that HGR upregulated carbohydrate, amino acid and fatty acids metabolism that determined secondary metabolism, nitrogen sequestration, cell membrane integrity, permeability and oxidation resistance. Hexadecanoic acid as a biomarker promoted root differentiation and increased the germination rate. Our discovery is a novel HGR that promotes aged seed germination, illustrates metabolic specificity among graphene-based materials and inspires innovative concepts in the regulation of seed development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Given that water is the most frequently used solvent and is ubiquitous in the natural environment, hydration is a high-priority item in nanomaterial chemistry and geochemistry. As the thinnest material (approximately 0.4 nm) ever invented, graphene (G) has been attracting a tremendous amount of attention in various fields due to its unique properties1,2,3,4. Graphene oxide (GO) with structural defects can adsorb H2O; simultaneously, H2O influences the layer and folding morphology of GO5,6. However, the hydration of G is still not well understood, especially for long-term exposure in an open atmospheric environment at the normal temperature and pressure.

After careful consideration, we expect to discover certain interesting applications of new nanomaterials, rather than be limited by changes of physicochemical properties. It is well reported that G destroys cell membranes and induces significant cytotoxicity7,8,9, although the biomolecular mechanisms are obscure. Recently, surface functionalization and morphology are thought to determine the biocompatibility of G7,10,11. Therefore, it will be an interesting finding that a new G characterized by specific-surface groups or morphology exhibits distinct, high biocompatibility compared with traditional G and GO12.

Seed germination is a critical phase of the plant life cycle resulting in many biological processes13,14. Seed germination combined with various catabolic and anabolic processes is sensitive to various internal and external stimuli15. Consequently, the regulation of seed germination by nanomaterials has been performed abundantly in the research16,17,18. However, the biomolecular regulations of nanomaterials on seed germination are unclear. Unlike genes and proteins, metabolites serve as direct signatures of biochemical activity and are easy to correlate with cellular biochemistries and biological stories19,20,21. Naturally, the metabonomics technology becomes a potential tool to analyze bioeffects of nanomaterials after genomics and proteomics7.

Herein, we discover a novel hydrated graphene ribbon (HGR) that shows few oxygen/nitrogen groups and disordered layer structures forming at the normal temperature and pressure (120 days hydration). Compared with G and GO, HGR promotes aged (two years) seed germination and root differentiation and reduces oxidative stress. The metabonomics analysis reveals HGR upregulates carbohydrate, amino acid and fatty acid metabolism that determine secondary metabolism, nitrogen sequestration, cell membrane integrity, permeability and oxidation resistance. This work discovers a novel HGR that promotes aged seed germination, illustrates metabolic specificity among graphene-based materials (GBMs) and inspires innovative thinking in the regulation of seed development.

Results

Few oxygen/nitrogen groups generate in HGR

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) is an essential tool used to reveal the surface chemistry of nanomaterials22,23. Compared with G, the contribution of O1s increases and a new peak of N1s occurs in HGR, as shown in Figures 1a and b. The atomic concentrations of O1s were 5.9% and 17.1% in G and HGR, respectively. The atomic concentration of N1s was 0.9% in HGR. The only component of G O1s is O = C (100%), while the components of HGR O1s involve -OH (82.6%) and O-C (17.4%), as described in Figures 1c and d. The specific component of HGR N1s includes pyridinic-N (398.6 eV, 11.9%), pyrrolic-N (399.5 eV, 77.3%) and graphene-N (401.2 eV, 10.8%)23, as presented in Figure 1e. These interesting results demonstrate that G gradually (hydration was performed at 120 days) reacts with oxygen and nitrogen in water at the normal temperature and pressure.

HGR presents disorder-layer and ribbon morphology

Furthermore, the morphology of G and HGR is studied, as illustrated in Figure 2. The atomic force microscope (AFM) image of G exhibited approximately 0.8 nm thickness and multilateral-sheet morphology. HGR presented ribbon morphology with approximately 0.38 nm thickness. The widths and lengths of ribbons were approximately 0.4 μm and 2.0 μm, respectively, as presented in Figure 2b. Interestingly, there are highlighted lights that surround the HGR edges, as shown in Figure 2b. The thickness of highlighted lights was approximately 7.1 nm. The field emission transmission electron microscopy (FETEM) image of G exhibited straight streaks, thereby demonstrating the orderly packing of layers. The interval of streaks was approximately 0.4 nm, which agreed with the thickness of single layer G24. In contrast, the streaks of HGR were twisted and disordered, which suggested that the packing of layers was untidy. The disordered-layer structure was probably owing to the highlighted lights in the AFM image. The interval of streaks was approximately 0.5 nm and slightly higher than that of G. The modified oxygen and nitrogen groups probably produced the highlighted lights. Finally, hydration induced the morphological transformation of G.

HGR promotes aged seed germination

Effects of GBMs on aged seed germination of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) are presented in Figure 3. The germination rate of aged seeds was 93% in the control group. G and GO inhibited germination with the same germination rate of 87%, while HGR significantly (P = 0.03) promoted germination with a 100% germination rate. Similarly, fresh weight, germinal length, root length and root differentiation (number) of wheat were inhibited by G and GO, while germination was obviously developed by HGR. The concentrations of malondialdehyde (MDA) reflecting lipid peroxidation were 13.2, 12.5 and 8.8 mg/g in the control, G and HGR groups, respectively. The main antioxidant enzyme (superoxide dismutase, SOD; catalase, CAT; peroxidase, POD) activities were also disturbed by GBMs. In summary, GO led to a lower toxicity than G, but both inhibited seed germination. GO had more oxygen and nitrogen groups than HGR (information about GO is described in Figures S1–S3 and the nitrogen groups of GO are from NaNO3 used in the synthetic process of GO). These results demonstrate that the modification of oxygen/nitrogen groups is not a direct reason to promote seed germination by HGR. The morphology of HGR probably plays a dominant role in the promotion of wheat seed germination.

Effects of GBMs on the germination of aged wheat seeds.

(a) Seed germination images of wheat exposed to the control (pure water) and GBMs (G, HRG and GO). The inserted images show distinctly inhibited seed germinations. (b) Seed germination rate, fresh weight of wheat, content of chlorophyll a (Ca), ratios of chlorophyll a to chlorophyll b (Ca/b) and activity of SOD of wheat exposed to the control and GBMs. (c) Germinal average length, root average length, root number per wheat, content of MDA, activity of CAT and POD of wheat exposed to the control and GBMs. The significant level at P < 0.05. Units of these biochemical parameters: germination rate, 0–1 representing to 0–100%; fresh weight of wheat, g; Ca, mg/g; germinal average length, cm; root average length, cm; MDA, mg/g; SOD, U/mg/protein; CAT, U/g/protein; POD, U/mg/protein.

GBMs induce the metabolic specificity

The metabonomics analysis revealed how G, HGR and GO regulated seed germination. Gas chromatography - mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (GC-MS/MS) analyses were performed to determine the relative levels of metabolites in the leaves, seeds and roots of wheat, as shown in Figures S4–7. A total of 200 peaks were analyzed in each sample and 65 metabolites (alkanes include C4, C16, C17, C21, C22, C25, C26 and C28) were identified, as shown in Tables S1–3. As illustrated in Figure 4a, the principal component analysis (PCA) demonstrates that metabolites are tissue-specific in the same plant. Scores of metabolites in the HGR group were largely separated from that in other groups, especially for seed and root tissues. Moreover, the orthogonal projection to latent structures – discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) was performed, as described in Figures 4b–d. Fresh weight, chlorophyll a and chlorophyll a/b as Y variables represent the growth activity and photosynthesis of plants. The dispersed distribution of scores with good model parameters (R2X, more than 0.7; R2Y, 1; Q2, more than 0.9) indicated the differences of plant growth activity and photosynthesis among the exposed groups. For germination rate and root differentiation as Y variables (R2X, 1 and 0.755; R2Y, 1 and 0.997; Q2, 1 and 0.952), the scores were clearly divided into three clusters (the control, G/GO and HGR) as shown in Figure 4c, thus implying the metabolic specificity. MDA, SOD, POD and CAT representing oxidative stress were set as Y variables, respectively. There were distinct separations of scores between the control and GBMs groups, indicating that GBMs posed oxidative stress to seed germination. Overall, the PCA and OPLS-DA analysis proposed that metabolisms were specific among GBMs groups.

The metabolic cluster analysis of wheat in the control and GBM (G, HGR and GO) groups.

(a) Metabolic cluster analysis of different tissues using PCA scores plot. (b) Metabolic cluster analysis of whole wheat using OPLS-DA scores plot. (c) Metabolic cluster analysis of seeds using OPLS-DA scores plot. (d) Metabolic cluster analysis of leaves using OPLS-DA scores plot.

High VIP metabolites link GBMs exposure and seed germination together

The cumulative variables important to projection (VIP) values were calculated to ascertain which variables contributed most to the model of OPLS-DA. The top five VIP variables in the OPLS-DA model are labeled in Figure 5. Hecadecanoic acid, mannose, asparagine, glucose, threonine and alanine were identified as the metabolites of the top five VIP (values more than 1.4) relating to germination rate and root differentiation, as labeled in Figure 5a. The first 4 metabolites were upregulated by HGR and were downregulated by G in seeds. By comparing the control and HGR, G and GO enhanced the content of alanine. Therefore, alanine was proposed to relate to the inhibition of seed germination. Inositol and valine with VIP values more than 1.2 regulated the growth and photosynthesis in whole wheat, as illustrated in Figure 5b. Compared to G and GO, the control and HGR developed the anabolism of both inositol and valine. Tyrosine, arabinofuranose, gluconic acid and aconiticacid with VIP values more than 1.2 correlate to oxidative stress, such as MDA, SOD, POD and CAT in leaves, respectively, as shown in Figure 5c. Compared to G, HGR downregulated arabinofuranose, gluconic acid and aconiticacid anabolisms and upregulated tyrosine anabolism. The metabolites of the top VIP values present good relevance to the corresponding Y variables, as shown in Figure 6. In particular, the correlation coefficients of hexadecanoic acid with root differentiation and germination rate were 0.98. Interestingly, when 10 mg/L hexadecanoic acid was supplemented in G exposed groups, the root differentiation and germination rate increased by 68% and 15%, respectively. Therefore, hexadecanoic acid regulates seed germination and root differentiation and is identified as a new biomarker of wheat exposed to GBMs.

HGR upregulates carbohydrate, amino acid and fatty acid metabolisms

The main metabolic pathways of wheat exposed to GBMs are described in Figure 7. The content of glucose as an important energy resource was higher in HGR group than that in G and GO groups. Given that glycolysis is the potential main pathway of glucose consumption, G or GO probably initially inhibited glycolysis to reduce the germination rate and root differentiation. Moreover, G developed the catabolism of glucose to produce guconic acid that disturbed glycolysis and interrupted the metabolic flux from glucose to glucopyranoside and glucopyranose. The contents of mannose, sorbose and maltose were also the highest in the HGR group. Therefore, HGR triggered the upregulation of carbohydrate metabolism to excite aged seed germination. Products of glyceric acid-3-P catabolism included glyceric acid, serine and inositol as the top VIP metabolites of growth and photosynthesis and were upregulated by HGR compared to G, as shown in Figure 7. G and HGR promoted phenylalanine and tyrosine metabolism, respectively, indicating the alterations in shikimate-mediated secondary metabolisms. For example, lanostane as one secondary metabolism was upregulated by HGR in whole wheat. Phenylalanine and tyrosine were high VIP metabolites of SOD and MDA, respectively, thus indicating the relationships between metabolites, oxidative stress and G exposure. Pyruvate was located at the key point between glycolysis and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. Here, the contents of pyruvate was negatively correlated to plant fresh weight (R2 = 0.95) and were the lowest in the HGR group. The low content of pyruvate may be attributed to the precursor consumption and enhancement of catabolisms, as shown in Figure 7. Hexadecanoic acid and octadecadienoic acid were the highest VIP metabolite of seed germination and the top VIP metabolite of MDA, respectively. The contents of both metabolites were the highest in HGR compared to the control, G and GO. This result indicated the enhancement of fatty acid metabolisms governed seed germination and lipid peroxidation resistance. The asparate metabolism involved three top VIP amino acids: threonine, asparagine and lysine. Here, the content of threonine was correlated to the CAT activity in leaf growth and seed germination. The glutamate metabolism involves two top VIP amino acids: glutamine and praline. Compared to the control, the amino acid metabolism, including alanine, leucine, isoleucine and valine, was downregulated in GBMs. The intermediates of the TCA cycle were also inhibited by GBMs.

The metabolic pathway map labeled with high VIP metabolites (blue) of wheat exposed to GBMs.

Inserted thermal maps represent the relative abundance of metabolites. In thermal maps, the four columns from left to right represent the control, G, HGR and GO groups, respectively. Numbers in brackets represent the color range of thermal maps from the lower limit to the upper limit. Solid and dash lines represent direct and indirect reactions, respectively. S, seed; L, leaf; W, whole wheat; G, germination rate; R, root differentiation; F, fresh weight; Ca, chlorophyll a; Ca/b, ratio of chlorophyll a to chlorophyll b.

Discussion

This novel HGR with few oxygen/nitrogen groups, disordered-layer and thick ribbon morphology differed from traditional G and GO, as shown in Figures 1, 2 and S1. Nanomaterials were transformed into nanomaterial oxides by acute treatment, such as oxygenant or UV irradiation24,25. The previous work also showed that GO modified nitrogen from NH3 at temperatures higher than 300°C26. Interestingly, this work revealed that G was gradually oxidized and modified nitrogen at the normal temperature and pressure. As is well known, the functionalization influences the bioavailability of G7,27. However, HGR rather than G or GO excited the aged seed germination, thereby suggesting that absolute oxygen and nitrogen groups were not the direct reasons for improving the biocompatibility of G. Recently, the G nanoribbon was thought to trigger cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of cells28,29. In this work, a thick G ribbon with a disordered-layer structure was formed during long-term hydration (120 days). The width of HGR ribbons was approximately two-fold larger than reported G nanoribbons and the thickness of HGR was half of that of reported G nanoribbons30,31. In addition, the raised bright spot around the HGR edges was obviously different with reported G nanoribbons. Herein, it was supposed that the insertion of oxygen and nitrogen drove the specific disordered-layer and thick ribbon morphology that further excited the aged seed germination.

There is the abundant evidence that reactive oxygen species (ROS), the products of G exposure to living organisms, lead to lipid peroxidation and disturb antioxidant enzyme systems32. The redox status was thought to mediate cell differentiation/reproduction and seed germination33,34,35,36. MDA as an indicator of lipid peroxidation was downregulated by HGR. Antioxidant enzyme systems (CAT, POD and SOD) of plants were also distinctly regulated by HGR. Stress conditions over-expressed SOD and POD and enhanced the seed longevity and germination rate of plants37. However, GO induced higher activities of SOD and POD than HGR. Therefore, antioxidant enzyme activities did not directly indicate the germination situation of seeds exposed to GBMs.

To identify how hydration reduced G toxicity and promoted seed germination, the metabolic paths of seed germination were explored. Glucopyranoside and glucopyranose play critical roles in the defense of oxidative stress38 and were upregulated by HGR compared with G. Glucose and mannose have osmoprotective and antioxidant roles to extrinsic stress39 and were also upregulated by HGR. The decrease of maltose relates to oxidative stress via formation of ROS40. Here, HGR enhanced the content of maltose, thus demonstrating that the oxidative stress induced by HGR was gentle. GBMs caused changes in the metabolism of inositol, thus implying alterations to functions of cell membranes, since inositol is an important component of cell membrane phospholipids41. These results demonstrate that HGR causes upregulation of the carbohydrate metabolism that plays osmoprotective, antioxidant and cell membrane phospholipids roles in seed germination.

Aromatic amino acids (tyrosine and phenylalanine) are synthesized through the shikimate pathway and serve as precursors for a wide range of secondary metabolites42,43. In the presented work, a secondary metabolite, lanostane, was upregulated by HGR and governed the fresh weight of wheat. Threonine biosynthesis was affected by the intraceulluar redox status34 and was upregulated by HGR. Asparagine and glutamine play central roles in nitrogen transport and storage in plants44 and were upregulated by HGR compared with G and GO. Given asparagine and glutamine had high VIP values for root differentiation and contents of chlorophyll a, it was proposed that nitrogen sequestration was related to root differentiation and photosynthesis. In addition, glutamine and lysine serve as primary precursors for stress related metabolites, such as γ-aminobutyrate45. The increasing content of proline in plant species is thought to provide an osmoprotective function by acting as an electron sink to reduce the amount of singlet oxygen46,47. Compared to G and GO, HGR increased the content of proline that was a high VIP metabolite for wheat fresh weight and chlorophyll a/b. These results demonstrate that HGR regulates amino acid metabolism fluxes to improve secondary, osmoprotective and nitrogen metabolites that promote seed germination.

HGR also upregulated the content of fatty acids, such as hexadecanoic acid and octadecadienoic acid, that were discovered to relate to seed germination and antioxidation. The unsaturated fatty acid (hexadecanoic acid) improves membrane fluidity48, which may resist membrane damage from G. Given that alanine and leucine in proteins are 7.5 mol% and 9.0 mol%, respectively, the increase of both amino acids indicates protein breakdown49. There was no obvious increase of both amino acids, thus suggesting GBMs did not induce the breakdown of proteins. Branched chain amino acids (BCAAs), including leucine, isoleucine and valine provide an alternative source of energy in sugar50. Compared to the control, GBMs led to an approximately 50% and 33% to 67% reduction of BCAAs and chlorophyll a, respectively. The downregulation of chlorophyll a increases oxidative respiration in order to provide cellular energy51, while the intermediates of the TCA cycle were also downregulated by GBMs. Decrease of TCA cycle intermediates only distinctly influenced the activity of POD and CAT in wheat leaves, as shown in Figure 7. It was suggested that metabolisms of the TCA cycle and BCAAs were not sensitive to seed germination.

In summary, a novel HGR with few oxygen/nitrogen groups, disordered-layer structures and thick ribbon morphology was formed at the normal temperature and pressure. Compared to G and GO, HGR promoted aged seed germination and root differentiation and relieved oxidative stress. Furthermore, the metabonomics analysis revealed distinct differences between HGR and G/GO. HGR promoted carbohydrate, amino acid and fatty acid metabolisms that determined secondary metabolism, nitrogen sequestration, cell membrane integrity, permeability and oxidation resistance. This discovery is a novel HGR that promotes aged seed germination, illustrates metabolic specificity among GBMs and inspires innovative thinking in the regulation of seed development.

Methods

Long-term hydration of G

G and GO nanosheets were obtained from the Nanjing XFNANO Materials Tech Co., Ltd., China. The single layer G was prepared by thermal exfoliation reduction and hydrogen reduction. GO was synthesized using Hummer's method. The physicochemical properties of G and GO are provided in Figures 1, 2 and S1–3. G 0.02 g was suspended in 200 ml pure water (18.2 Ω/cm) by ultrasonic apparatus running for 40 min at 400 W. Next, suspended G was placed in a light incubator maintaining 3000 Lx irradiation, 24°C temperature and 80% humidity. The hydration was conducted for 120 days. During the hydration, pure water was complemented to keep the volume at 150–200 ml. Finally, water was evaporated and then lyophilized to collect HGR. XPS measurements were conducted using an Axis Ultra XPS system (Kratos) with a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV). The spectra were analyzed using Casa-XPS V2.3.13 software. The peak deconvolutions were performed using Gaussian components after a Shirley background subtraction. AFM and TEM were performed on Veeco Nanoscope 4 and JEM-2010 FEF, respectively.

Seed germination

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seeds were aged for two years in the dark at 24°C and 40–50% humidity. Before germination, seeds were sterilized for 20 min using 2% H2O2. Subsequently, seeds were completely rinsed using pure water. Double-layer filter paper (diameter, 9 cm) was paved in culture dish. GBMs (G, GO and HGR) (6 ml 200 mg/l) were added in three culture dishes, respectively. Pure water (6 ml) as the control replaced GBMs. In each culture dish, 15 seeds were germinated. Culture dishes were placed in a light incubator at 3000 Lx irradiation, 24°C temperature and 80% humidity. Germination was performed for five days. Fresh weight, leaf length, root length and root differentiation (number) were recorded using the plant analyzer (EPSON PerfectionV700 Photo, SilverFast STD4800). The activity of SOD, CAT and POD and the content of MDA were analyzed as in the previous work52.

Metabolic analysis

Fresh tissues (about 0.1–0.2 g) were ground in liquid nitrogen. A 2 ml solution (ratio of volume, methanol: chloroform: water = 2.5:1:1) and 0.2 mg/ml ribitol (50 μl) as the internal standard were added. Metabolites were intensively extracted using ultrasound (400 W, 10 min) in an ice-bath and centrifuged for 100 min at 11000 g and 4°C. The supernate was collected. The sediment was extracted again using 1 ml solution (ratio of volume, methanol: chloroform = 1:1) as the above ultrasound and centrifugation. The supernate was mixed with the first supernate. Water (500 μl) was added and then centrifuged at 5000 g for 3 min. The down-layer solution was dried by nitrogen blow-off. For the up-layer solution, methanol was blown away by nitrogen and then water was lyophilized. Methoxamine hydrochloride (20 mg/ml, 50 μl) and N-methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (80 μl) were used as derivatives. Samples (1 μl) were injected into the GC column in the split mode (1:5). GC (Agilent 6890N, Agilent Technologies, USA) linked to a quadrupole MS (Agilent 5973, Agilent Technologies, USA) was used to analyze metabolites. GC separation was achieved on a DB-5 MS capillary column (30 m, 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness). The injection temperature was 230°C and the transfer line and the ion source were set at 250°C. The spectrometer was operated in the electron-impact mode. The detection voltage was 2100 V. The full scan range was from 60 to 800 amu. Helium as the carrier gas was set at a constant flow rate of 2 ml/min. The oven temperature was maintained at 80°C for 2 min and then increased at a rate of 15°C/min to 320°C and held for 6 min. Metabolites were identified by the NIST 08 library. The PCA analysis and the OPLS-DA analysis were performed using the SIMCA-P 11.5 software. The thermal map was drawn using the MeV 4.8.1 software.

References

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Roadmap for graphene. Nature 490, 192–200 (2012).

Singh, S. K. et al. Amine-modified graphene. Thrombo-protective safer alternative to graphene oxide for biomedical applications. Acs Nano 6, 2731–2740 (2012).

Xu, M., Liang, T., Shi, M. & Chen, H. Graphene-like two-dimensional materials. Chem. Rev. 113, 3766–3798 (2013).

Mao, H. Y. et al. Graphene: promises, facts, opportunities and challenges in nanomedicine. Chem. Rev. 113, 3407–3424 (2013).

Guo, F. et al. Hydration-responsive folding and unfolding in graphene oxide liquid crystal phases. Acs Nano 5, 8019–8025 (2011).

Luzan, S. M. & Talyzin, A. V. Hydration of graphite oxide in electrolyte and non-electrolyte solutions. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 24611–24614 (2011).

Hu, X. G. & Zhou, Q. X. Health and ecosystem risks of graphene. Chem. Rev. 113, 3815–3835 (2013).

Begurn, P., Ikhtiari, R. & Fugetsu, B. Graphene phytotoxicity in the seedling stage of cabbage, tomato, red spinach and lettuce. Carbon 49, 3907–3919 (2011).

Hu, X. G., Mu, L., Wen, J. P. & Zhou, Q. X. Covalently synthesized graphene oxide-aptamer nanosheets for efficient visible-light photocatalysis of nucleic acids and proteins of viruses. Carbon 50, 2772–2781 (2012).

Koenig, S. P., Boddeti, N. G., Dunn, M. L. & Bunch, J. S. Ultrastrong adhesion of graphene membranes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 543–546 (2011).

Lee, D. Y., Khatun, Z., Lee, J., Lee, Y. & In, I. Blood compatible graphene/heparin conjugate through noncovalent chemistry. Biomacromolecules 12, 336–341 (2011).

Georgakilas, V. et al. Functionalization of graphene: covalent and non-covalent approaches, derivatives and applications. Chem. Rev. 112, 6156–6214 (2012).

Feng, S. et al. Coordinated regulation of arabidopsis thaliana development by light and gibberellins. Nature 451, 475–U9 (2008).

Flematti, G. R. et al. Burning vegetation produces cyanohydrins that liberate cyanide and stimulate seed germination. Nat. Comm. 2, 1–6 (2011).

Nelson, D. C. et al. Karrikins enhance light responses during germination and seedling development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 7095–7100 (2010).

Yin, L., Colman, B. P., McGill, B. M., Wright, J. P. & Bernhardt, E. S. Effects of silver nanoparticle exposure on germination and early growth of eleven wetland plants. Plos One 7, e47674 (2012).

Ravindran, A., Prathna, T. C., Verma, V. K., Chandrasekaran, N. & Mukherjee, A. Bovine serum albumin mediated decrease in silver nanoparticle phytotoxicity: root elongation and seed germination assay. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 94, 91–98 (2012).

Castiglione, M. R., Giorgetti, L., Geri, C. & Cremonini, R. The effects of nano-TiO2 on seed germination, development and mitosis of root tip cells of Vicia narbonensis L. and Zea mays L. J. Nanopart. Res. 13, 2443–2449 (2011).

Moussaieff, A. et al. High-resolution metabolic mapping of cell types in plant roots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, E1232–E1241 (2013).

Patti, G. J., Yanes, O. & Siuzdak, G. Metabolomics: the apogee of the omics trilogy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Bio. 13, 263–269 (2012).

Baker, M. Metabolomics: from small molecules to big ideas. Nat. Methods 8, 117–121 (2011).

Jeon, I. Y. et al. Direct nitrogen fixation at the edges of graphene nanoplatelets as efficient electrocatalysts for energy conversion. Sci. Rep. 3, 2260; 10.1038/srep02260 (2013).

Sheng, Z. H. et al. Catalyst-free synthesis of nitrogen-doped graphene via thermal annealing graphite oxide with melamine and its excellent electrocatalysis. Acs Nano 5, 4350–4358 (2011).

Geim, A. K. & Novoselov, K. S. The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 183–191 (2007).

Guo, S. & Dong, S. Graphene nanosheet: synthesis, molecular engineering, thin film, hybrids and energy and analytical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 2644–2672 (2011).

Li, X., Wang, H., Robinson, J. T., Sanchez, H., Diankov, G. & Dai, H. Simultaneous nitrogen doping and reduction of graphene oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 15939–15944 (2009).

Park, J., He, G., Feenstra, R. M. & Li, A.-P. Atomic-scale mapping of thermoelectric power on graphene: Role of defects and boundaries. Nano Lett. 13, 3269–3273 (2013).

Chowdhury, S. M. et al. Cell specific cytotoxicity and uptake of graphene nanoribbons. Biomaterials 34, 283–293 (2013).

Akhavan, O., Ghaderi, E., Emamy, H. & Akhavan, F. Genotoxicity of graphene nanoribbons in human mesenchymal stem cells. Carbon 54, 419–431 (2013).

Sokolov, A. N. et al. Direct growth of aligned graphitic nanoribbons from a DNA template by chemical vapour deposition. Nat. Commun. 4, 2402–2402 (2013).

Martin-Fernandez, I., Wang, D. & Zhang, Y. Direct growth of graphene nanoribbons for large-scale device fabrication. Nano Lett. 12, 6175–6179 (2012).

Krishnamoorthy, K., Veerapandian, M., Zhang, L.-H., Yun, K. & Kim, S. J. Antibacterial efficiency of graphene nanosheets against pathogenic bacteria via lipid peroxidation. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 17280–17287 (2012).

Yanes, O. et al. Metabolic oxidation regulates embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 411–417 (2010).

Zhang, K., Li, H., Cho, K. M. & Liao, J. C. Expanding metabolism for total biosynthesis of the nonnatural amino acid L-homoalanine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 6234–6239 (2010).

Mahmoudi, M., Azadmanesh, K., Shokrgozar, M. A., Journeay, W. S. & Laurent, S. Effect of nanoparticles on the cell life cycle. Chem. Rev. 111, 3407–3432 (2011).

Song, G. et al. Physiological effect of anatase TiO2 nanoparticles on Lemna minor. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 31, 2147–2152 (2012).

Lee, Y. P. et al. Tobacco seeds simultaneously over-expressing Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase and ascorbate peroxidase display enhanced seed longevity and germination rates under stress conditions. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 2499–2506 (2010).

Amorini, A. M. et al. Cyanidin-3-O-beta-glucopyranoside protects myocardium and erythrocytes from oxygen radical-mediated damages. Free Radical Res. 37, 453–460 (2003).

Ye, Y., Wang, X., Zhang, L., Lu, Z. & Yan, X. Unraveling the concentration-dependent metabolic response of Pseudomonas sp HF-1 to nicotine stress by 1H NMR-based metabolomics. Ecotoxicology 21, 1314–1324 (2012).

Aslund, M. L. W. et al. Earthworm sublethal responses to titanium dioxide nanomaterial in soil detected by 1H NMR metabolomics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 1111–1118 (2012).

Chen, F. et al. Combined Metabonomic and quantitative real-time PCR analyses reveal systems metabolic changes of Fusarium graminearum induced by Tri5 gene deletion. J. Proteome Res. 10, 2273–2285 (2011).

Less, H. & Galili, G. Principal transcriptional programs regulating plant amino acid metabolism in response to abiotic stresses. Plant Physiol. 147, 316–330 (2008).

Korkina, L. G. Phenylpropanoids as naturally occurring antioxidants: from plant defense to human health. Cell. Mol. Biol. 53, 15–25 (2007).

Gaufichon, L., Reisdorf-Cren, M., Rothstein, S. J., Chardon, F. & Suzuki, A. Biological functions of asparagine synthetase in plants. Plant Sci. 179, 141–153 (2010).

Ye, Y., Zhang, L., Hao, F., Zhang, J., Wang, Y. & Tang, H. Global metabolomic responses of Escherichia coli to heat stress. J. Proteome Res. 11, 2559–2566 (2012).

Witt, S. et al. Metabolic and phenotypic responses of greenhouse grown maize hybrids to experimentally controlled drought stress. Mol. Plant. 5, 401–417 (2012).

Szabados, L. & Savoure, A. Proline: a multifunctional amino acid. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 89–97 (2010).

Mortimer, M., Kasemets, K., Vodovnik, M., Marinsek-Logar, R. & Kahru, A. Exposure to CuO nanoparticles changes the fatty acid composition of protozoa tetrahymena thermophila. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 6617–6624 (2011).

McKelvie, J. R., Yuk, J., Xu, Y., Simpson, A. J. & Simpson, M. J. 1H NMR and GC/MS metabolomics of earthworm responses to sub-lethal DDT and endosulfan exposure. Metabolomics 5, 84–94 (2009).

Taylor, N. L., Heazlewood, J. L., Day, D. A. & Millar, A. H. Lipoic acid-dependent oxidative catabolism of a-keto acids in mitochondria provides evidence for branched-chain amino acid catabolism in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 134, 838–848 (2004).

Bowne, J. B. et al. Drought responses of leaf tissues from wheat cultivars of differing drought tolerance at the metabolite level. Mol. Plant 5, 418–429 (2012).

Song, G., Gao, Y., Wu, H., Zhang, C. & Ma, H. Physiological effect of anatase TiO2 nanoparticles on Lemna minor. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 31, 2147–2152 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank Li Mu, Jia Kang, Kaicheng Lu, Yayuan Li, Rui Li and Yan Lu for their help in the preparation of samples and data analysis. This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China as key projects (grant Nos. 21037002 and U1133006), a youth project (grant No. 21307061) and the Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (grant No. 2013003112016). We are also grateful to the Key Laboratory of Regional Environment and Eco-Remediation, Ministry of Education, Shenyang University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Prof. Q.Z. organized, designed and guide the work and revised the manuscript. Dr X.H. designed, performed the research and worked out the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supporting information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, X., Zhou, Q. Novel hydrated graphene ribbon unexpectedly promotes aged seed germination and root differentiation. Sci Rep 4, 3782 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03782

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03782

This article is cited by

-

Nanomaterials coupled with microRNAs for alleviating plant stress: a new opening towards sustainable agriculture

Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants (2022)

-

Graphene oxide exhibited positive effects on the growth of Aloe vera L

Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.