Abstract

History of self-harm is the strongest predictor of suicide, but there are few national studies that estimate the risk of suicide following self-harm in a clearly defined clinical cohort. Records from the National Self-Harm Registry Ireland between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2017 (n = 23,764) were linked to national suicide records via the Irish Probable Suicide Deaths Study. The 12-month cumulative incidence of suicide for male, female and all persons was 1.3%, 0.6%, and 0.9%, respectively. Suicide risk was more than 80 times higher in the self-harm cohort relative to the general population. Associated factors included male sex, older age, attempted hanging as a method of self-harm, and self-harm history in the previous 12 months. This national study highlights the greatly elevated risk of suicide mortality following hospital-presenting self-harm. These findings reinforce the need to provide appropriate care and timely interventions for this patient group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Self-harm—intentional self-injury or poisoning, irrespective of motive—is associated with an increased risk of subsequent death, particularly through suicide1,2. Risk of suicide among individuals in the year after a suicide attempt has been estimated to be up to 100 times higher than for matched community controls3. Within 10 years, it is estimated that between 5% and 10% of adults who have self-harmed have died by suicide4.

Owens et al. found that suicide risk lies somewhere between 0.5% and 2.0%5, while a systematic review and meta-analysis by Carroll et al.6 similarly reported that one-year risk of suicide after self-harm was 1.6%. More recently, findings from a mortality follow-up study based on the Multicentre Study of Self-Harm in England have been published7. This study cohort consisted of 40,000 self-harm patients who presented to hospital in a ten-year period and showed that the one-year risk of suicide after self-harm was 0.5%, which is slightly lower than estimates from previous English studies.

In some Nordic countries, however, the ability to link nationwide registers of sociodemographic, health-related, and cause-of-death data provides detailed datasets and large sample sizes required for robust longitudinal studies8. Erlangsen et al.9 examined individuals presenting to hospital due to self-harm in Denmark over a 19-year period and found that the one-year risk of suicide was 1.2%. Fedyszyn et al.10 reported a similar, if slightly lower, one-year risk of suicide of 0.9%. These studies are based on large national populations, but it has been noted that hospital presentations due to suicidal behaviors are under-recorded in Danish hospital registers8. A Swedish study by Runeson et al.11 that was based on a study population of self-harm patients that were admitted to hospital, rather than all who presented to hospital due to self-harm, found that the one-year risk was 1.5%.

There has been some examination of age- and sex-specific suicide risk profiles among hospital-treated self-harm cohorts. Tidemalm et al.3 reported that, when comparing suicide risk in the self-harm group with controls, the highest incident rate ratios were among women under age 75. This finding of highest suicide risk among men but highest relative risk among women was also reported by Hawton et al.1 A violent index self-harm method has been found to be the strongest examined risk factor for suicide deaths in patients aged 20 years or older, particularly women3, while suicide risk was also found to be higher after attempts by hanging and other self-injury methods (versus self-poisoning) in the study by Runeson et al.11.

Suicide prevention strategies and interventions can benefit from a greater understanding of suicide risk after self-harm and of factors that may influence suicide risk. However very few high-quality national studies have been conducted that accurately estimate risk of suicide following self-harm. The current study uses data from the first and one of the very few dedicated national self-harm registries worldwide. The National Self-Harm Registry Ireland (NSHRI) records all self-harm presentations to emergency departments in Ireland12. The objectives of this study were to examine suicide risk among a large-scale national cohort of individuals who attended hospital emergency departments with self-harm in Ireland. To identify subgroups at elevated suicide risk after self-harm, models based on sex, age, self-harm method, and previous self-harm history were examined.

Results

Cohort characteristics

Between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2017, NSHRI records indicate 23,764 individuals presented to hospital after self-harm, of whom most (n = 12,919; 54.4%) were female. More than one-third of the cohort were aged under 25 years (8,861; 37.3%). More than half (14,142; 59.5%) of people presented to hospital with a drug overdose only, with 17.6% (4,184) presenting with self-cutting only. A minority presented with a combination of drug overdose and self-cutting (1,078; 4.5%), or with more lethal methods of self-harm such as attempted hanging (1,310; 5.5%) and attempted drowning (540; 2.3%). Just under one-third of individuals had consumed alcohol as part of the self-harm episode (7,456; 31.4%).

Most people were discharged from the emergency department after treatment (13,141; 55.3%). One-third (7,803; 32.8%) were admitted into the presenting hospital, with 25.7% (6,117) medically admitted and 7.1% (1,686) admitted to a psychiatric ward. A minority (2,820; 11.9%) left the emergency department before their treatment was completed or refused admission. Most received a psychosocial assessment as part of their hospital attendance (16,450; 73.2%).

A minority of individuals (4,066; 17.1%) had made at least one previous presentation to hospital following self-harm in the 12 months preceding their most recent (index) episode (Table 1).

Suicide following self-harm

The study follow-up time ranged from 1 to 1,095 days, with a median follow-up of 539 days. A total of 217 individuals (0.91%) died by suicide during the period of follow-up. For the whole study period (excluding individuals with less than 12 months follow-up), the 12-month cumulative incidence of suicide for male, female, and all persons was 1.30% (1.07–1.59), 0.60% (0.46–0.79), and 0.92% (0.79–1.08), respectively (Table 2).

The median time to death was 136 days (range: 1–967). Risk of suicide was greatest in the days and weeks following the most recent presentation to hospital with self-harm, with 84 (38.7%) of the suicides occurring in the first month, decreasing to 10.6% (23) in the second month and 8.3% (18) in the third month.

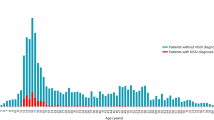

This 12-month risk of suicide after hospital-presenting self-harm was 81 times (95% confidence interval (CI): 46–145) higher in the self-harm population relative to the general population (Table 2). Among male individuals with a history of hospital-presenting self-harm, incidence of suicide was 69 times (44–109) higher than that of the general population. Among female individuals, the self-harm cohort had suicide risk 136 times (55–334) higher than the general population. Therefore, although absolute risk of suicide was higher among men than among women within the self-harm cohort, suicide risk was more elevated among women than among men in the self-harm cohort when compared with the general population. Risk of suicide following self-harm was most elevated among those in the youngest and oldest age groups—those aged under 25 years (101, 64–158) and those aged 55 years and older (142, 97–207)—while the lowest incident rate ratio of the self-harm group to the general population was in those aged 35–44 years (71, 50–100).

The most common method of suicide among those with a history of hospital-presenting self-harm was hanging (115; 53.0%), followed by poisoning (51; 23.5%) and drowning (26; 12.0%). Suicide by hanging was more common for men than for women (56.3% versus 46.7%), while suicide by poisoning was more common among women than among men (32.0% versus 19.0%).

Factors associated with suicide following self-harm

Table 3 details the results from the unadjusted and adjusted Cox proportional hazard models. In the adjusted models, characteristics of an individual’s most recent self-harm act associated with subsequent suicide included male sex (hazard ratio = 1.88, 95% CI: 1.39–2.56) and increasing age (55+ years: 4.60, 2.81–7.53) (Table 3 and Fig. 1a,b). Compared with drug overdose, attempted hanging as the method of self-harm was associated with a five-fold increased risk of suicide (5.09, 3.35–7.71). Attempted drowning was associated with a more than two-fold increased risk of subsequent suicide (2.25, 1.03–4.91). Individuals who consumed alcohol as part of their self-harm had a lower risk of subsequent suicide (0.65, 0.46–0.92). Patients receiving medical admission were associated with an increased risk of suicide (2.37, 1.71–3.28) compared with those who were discharged from the emergency department following treatment. Previous self-harm history was also positively associated with risk of suicide, highest in those with two or more presentations in the year before their most recent presentation (4.56, 3.04–6.82) (Table 3 and Fig. 1c). The likelihood ratio tests assessing the fully adjusted model with and without each variable were all statistically significant at P < 0.05, except for psychiatric review, which was not a significant factor.

Sex-specific models highlighted the relatively increased risk of suicide among women aged 25 years and over, and it was highest among women aged 55+ years (5.61, 2.38–13.23). A combination of self-cutting and drug overdose as a method of self-harm was associated with an increase in suicide risk among men only (2.30, 1.03–5.11), while attempted hanging as self-harm method was associated with increased risk of suicide for both men (4.73, 2.88–7.77) and women (6.41, 3.00–13.66). The incremental increase in risk of suicide according to number of previous self-harm presentations was similar for both men and women (Table 4).

Discussion

In this national cohort study of nearly 24,000 individuals with hospital-presenting self-harm, 0.9% had died by suicide within 12 months, with absolute risk of suicide higher in men than in women (1.3% compared with 0.6%). The relative risk of suicide among the self-harm cohort compared with the general population was more increased among women. Specifically, women with hospital-presenting self-harm were nearly 140 times more likely to die by suicide within 12 months than the general population, whereas men were 70 times more likely to die by suicide than the general population. Several key factors associated with risk of subsequent suicide were identified in the study cohort. Increasing age was associated with greater suicide risk after self-harm, as were attempted hanging as the method of self-harm and previous history of self-harm.

The present study overcomes some of the methodological challenges identified in previous research, including the lack of national recording systems for hospital-presenting self-harm and issues with accurate recording of self-harm within health systems. Suicide risk in the 12 months following self-harm presentation among this national cohort in Ireland was significantly higher than reported in a regional English study, which found a 0.5% suicide risk in the follow-up period7. The absolute risk of suicide we have reported is lower, however, than that reported in Danish national studies9,10.

In this study, the most increased risk of suicide, both in absolute terms and when compared with general population rates, was among those aged over 55 years presenting to hospital following self-harm. Previous research has found that age was positively related to suicide risk following self-harm in both sexes, with an English study reporting a 3% increase in risk for every one-year increase in age at hospital presentation7. A French study that examined mortality following hospital admission due to self-harm also reported increased risk of suicide and other mortality with increasing age2. A recent meta-analysis of studies examining factors associated with suicide following self-harm reported highest suicide risk in older adults13. Older adults may present a distinct profile, with higher suicidal intent associated with self-harm than among those presenting in middle age and with differing associated factors14. Our findings of elevated suicide risk underline the need for appropriate psychosocial assessment and next care for older adults following self-harm to reduce fatal and non-fatal repetition.

Our findings of associations between self-harm method and suicide risk are in keeping with international evidence. In particular, attempted hanging or self-cutting signals elevated suicide risk compared with intentional drug overdose. A similar finding was reported by an English study using a comparable methodology7. In a Swedish study of adolescents and young adults, use of a violent self-harm method (including hanging, firearms, and drowning) by adolescents was associated with a nearly eightfold increase in suicide risk compared with self-poisoning. Among young adults, risk increased fourfold for both cutting and violent methods for women, while method of self-harm did not affect suicide risk in young adult men15. Previous research has found that a self-harm act with combined methods of self-poisoning and self-injury was associated with elevated risk of suicide compared with those whose self-harm method was poisoning only16. Our findings also show an elevated risk associated with combined intentional drug overdose and self-cutting for men when compared with either method alone, although the highest risk of suicide overall was among those with attempted hanging. Further analysis is needed to examine method of death and associations with previous self-harm methods among those who died by suicide.

Interestingly, those whose past-year self-harm presentation involved alcohol were significantly less likely to die by suicide than those without. Although associations between acute alcohol use and increased risk of self-harm17 and suicide18 have been established, few studies have examined longer-term outcomes among those whose self-harm presentation involved alcohol. Acute alcohol use at the time of self-harm has been found to be associated with increased risk of suicide in a French cohort study19, whereas a Finnish national study found no such association20. An English study found alcohol problems at the time of self-harm were associated with increased risk of other causes of premature death21. It may be the case that the profile of this subgroup with alcohol involvement is clinically less severe in terms of other indicators of risk or reflects the disinhibiting effect of alcohol in terms of self-harm. This suggestion is supported by a previous study, which found that those presenting with self-harm with acute alcohol use had lower self-reported suicidal intent, despite having similar clinical features22.

History of previous self-harm presentations was examined for this cohort, with multiple presentations in the previous 12 months associated with elevated risk of suicide. A recent systematic review reported similar findings13. Further research could examine the trajectory and timing of self-harm presentations and associations with long-term outcomes, as the authors of a national registry study from Taiwan reported that, as well as switching to more lethal methods, the time interval of the last two non-fatal attempts was a significant predictor of suicide23. Our findings also demonstrate that the risk of suicide was greatest in the days and weeks following presentation to hospital with self-harm. This reflects, broadly, patterns of repeat self-harm and suicidal ideation12,24,25, which underlines the importance of appropriate safety planning and timely follow-up and referral in the period following presentation to hospital with self-harm26,27.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is the use of data from the NSHRI to carry out a national cohort study. The NSHRI is a national system for the monitoring of hospital-treated self-harm that uses standardized definitions and inclusion criteria, with collection of data by trained data registration officers. Cases are recorded only if there was a clear intention to self-harm. However, limited demographic data are collected, and detailed clinical data regarding hospital presentations involving self-harm, such as psychiatric history, psychiatric diagnoses, and levels of suicidal intent, are not available. An additional strength of this study is the robust methodology of the Irish Probable Suicide Deaths Study (IPSDS), which collected complete national coronial data on probable suicides within the study period.

The deterministic record linkage methodology used in this study requires matching variables to agree exactly across record pairs to be considered a match. As any coding errors in the matching variables may result in some true matches being missed, deterministic record linkage is generally best used when a single unique identifier (such as a social security number or NHS number) is available28. Unique identifiers were unavailable for this study; therefore, the data may have included missing information or data entry errors. Nonetheless, data from both sources are gathered and recorded in a systematic way, by trained researchers and data registration officers, minimizing the opportunity for coding errors. In the study, we were not able to estimate risk of suicide according to degree of suicidal intent at the time of the most recent self-harm presentation. It is a further limitation that we do not know if some participants were lost to follow-up due to leaving the country or dying by other causes during the study period. Finally, owing to the relatively small number of people in the self-harm cohort, the comparisons of suicide rates between this cohort and the general population have wide confidence intervals.

While this study focused on suicide mortality, further research should examine associations between self-harm and subsequent mortality from other causes. Internationally, research has identified elevated risk of short- and long-term mortality from all causes among those with a history of hospital-treated self-harm2. A Swedish cohort study reported a dramatic reduction in life expectancy after a suicide attempt, with suicide deaths accounting for 20% of mortality within ten years of the suicide attempt29.

Conclusion

This examination of a national cohort of patients with hospital-presenting self-harm has found that risk of suicide is elevated in the period after self-harm, with one-year suicide risk in this cohort a little below 1%. Several factors associated with suicide risk have been identified, including male sex, older age, and attempted hanging as the self-harm method. However, prediction of suicide risk remains very difficult, and all patients should receive appropriate after-care to reduce mortality.

Methods

Setting and sample

Via the NSHRI30, we identified individuals who had presented to hospital following self-harm between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2017, representing a total of 23,764 persons. Most (n = 12,919; 54.4%) were female, and more than one-third were aged under 25 years (8,861; 37.3%). The NSHRI defines self-harm as “an act with non-fatal outcome in which an individual deliberately initiates a non-habitual behavior, that without intervention from others will cause self-harm, or deliberately ingests a substance in excess of the prescribed or generally recognized therapeutic dosage, and which is aimed at realizing changes that the person desires via the actual or expected physical consequences”31. This definition is consistent with that used in similar registries, including the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England study32, and includes acts involving varying levels of suicidal intent and various underlying motives such as loss of control, cry for help, and self-punishment. Data on self-harm are collected by dedicated data registration officers who operate independently of the hospitals with a standardized application of case definition and inclusion/exclusion criteria30.

The full dataset from NSHRI contained the following variables: age, sex, date of attendance, method(s) of self-harm according to ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision) (X60–X84)33, and clinical management of self-harm in the hospital. Area of residence was geo-coded to electoral division, of which there are 3,409 in Ireland.

For those who presented to hospital with self-harm on more than one occasion during the study period, data from the most recent episode were analyzed. Furthermore, self-harm repetition in this study was defined on the basis of the number of presentations in the 12 months preceding the most recent episode.

Suicide data

Data on suicides that occurred during the study period 2015–2017 were obtained from the IPSDS34. The study gathers data from closed coronial files in all coroner districts in Ireland using a standardized methodology35. In Ireland, official suicide figures are based on a standard of proof used by the coronial system, whereby the coroner must be satisfied ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ that the person intended to take their own life for a verdict of suicide to be given34. The IPSDS uses broad inclusion criteria using both coroners’ verdicts and expert consensus concerning the identification of suicidal intent through coroners’ records. Specifically, the IPSDS includes deaths where there was a verdict of suicide or suicide-equivalent verdict. It also includes cases where there was evidence that the death was intentional, in line with the Rosenberg criteria of suicide36. In this way, cases are included where (1) hanging was the cause of death, with no evidence to suggest it was accidental, and/or (2) where a contemporaneous, relevant suicide note is present, and/or (3) where there was other evidence of intent, such as expression of farewell or inappropriate preparations made for death. In addition, cases are included where there was evidence of two or more risk factors for suicide present (for example, history of self-harm, current symptoms of a significant mental illness, or evidence of a significant stressful event)37. Any ambiguous cases are discussed by an expert review group before inclusion34. The approach used by the IPSDS in the recording of suicide deaths is less reliant on the coroner’s verdict and thus is probably an accurate reflection of the number of suicides in Ireland, based on the balance-of-probabilities approach, in line with the approach taken in other jurisdictions such as Scotland and England34.

The variables on suicide deaths obtained from the IPSDS included sex, age, method of suicide, and the date that the suicide occurred.

Data linkage

To identify suicide following hospital-presenting self-harm, data from the NSHRI and data from the IPSDS were electronically linked. In lieu of a national unique health identifier, the NSRHI generates a unique identifier for each presentation recorded, using a combination of selected letters from the person’s name, sex, and date of birth. The software used to generate this identifier was used to generate identifiers for cases in the IPSDS, by the researchers who had access to necessary information from the records. Self-harm and suicide records with identical codes were matched (deterministic matching).

Statistical analysis

Crude and European age-standardized suicide rates per 100,000 for male, female and all persons were calculated for the self-harm cohort and for the general population in the country. The latter used cases of suicide where there was no history of hospital-presenting self-harm as the numerator and annual population estimates from the Central Statistics Office as the denominator38. We calculated 95% CIs for these rates using the normal approximation for the Poisson distribution. Poisson regression models were used to establish the 12-month risk of suicide of the last episode of self-harm compared with the general population, according to sex and age group. Patients who had a follow-up of less than 12 months (that is, presented to hospital between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2017) were excluded in the calculation of the rates and incidence rate ratios.

Kaplan–Meier analyses were used to estimate the cumulative incidence of suicide in the self-harm population. Survival time began from the date of the most recent self-harm presentation and ended at either death or the end of the study period. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard models were developed to identify factors relating to suicide during the follow-up period. The following variables related to the individual’s self-harm presentation were included: sex, age group, method of self-harm, date and time of presentation, alcohol involvement, provision of psychosocial assessment, and recommended next care. Multivariable models were also adjusted for area-level social deprivation, on the basis of an individual’s area of residence (electoral division), measured by the Pobal HP Deprivation Index39. Electoral divisions were divided into quintiles on the basis of the absolute score (quintile 1 = 20% most deprived areas; quintile 5 = 20% least deprived areas). It was not possible to assign a deprivation score to 1,377 (5.8%) of cases due to an area of residence not being recorded.

All variables significant at P < 0.2 at a univariable level were included in the multivariable models. Sex-specific models were also generated. Results were expressed as hazard ratios with 95% CIs. To assess the relative contribution of each predictor variable, likelihood ratio tests were undertaken to assess each variable’s contribution to the fully adjusted model, compared with that variable not being included.

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 27.0) and StataCorp LLC (release 16).

Ethical approval

This study has received ethical approval from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Cork Teaching Hospitals (reference number ECM 4 (f) 13/08/19). Ethical approval for the NSHRI has been granted by the National Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Public Health Medicine and from individual hospital or regional health committees. The NSHRI has received a waiver of consent by the Irish Health Research Consent Declaration Committee. Ethical approval for the IPSDS was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Irish College of General Practitioners.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

As per the conditions of the NSHRI and the IPSDS, data can be shared only on request. Requests to access data from the NSHRI should be made via infonsrf@ucc.ie. For any information on the data used from the IPSDS, contact should be made via info@nosp.ie.

Code availability

Requests to access the underlying code for the analysis in this manuscript can be made via the corresponding author.

References

Hawton, K. et al. Suicide following self-harm: findings from the Multicentre Study of self-harm in England, 2000–2012. J Affect. Disord. 175, 147–151 (2015).

Vuagnat, A., Jollant, F., Abbar, M., Hawton, K. & Quantin, C. Recurrence and mortality 1 year after hospital admission for non-fatal self-harm: a nationwide population-based study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 29, e20 (2019).

Tidemalm, D. et al. Age-specific suicide mortality following non-fatal self-harm: national cohort study in Sweden. Psychol. Med. 45, 1699–1707 (2015).

Gibb, S. J., Beautrais, A. L. & Fergusson, D. M. Mortality and further suicidal behaviour after an index suicide attempt: a 10-year study. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 39, 95–100 (2005).

Owens, D., Horrocks, J. & House, A. Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm. Systematic review. Br. J. Psychiatry 181, 193–199 (2002).

Carroll, R., Metcalfe, C. & Gunnell, D. Hospital presenting self-harm and risk of fatal and non-fatal repetition: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 9, e89944 (2014).

Geulayov, G. et al. Suicide following presentation to hospital for non-fatal self-harm in the Multicentre Study of Self-harm: a long-term follow-up study. Lancet Psychiatry 6, 1021–1030 (2019).

Nordentoft, M. Prevention of suicide and attempted suicide in Denmark. Epidemiological studies of suicide and intervention studies in selected risk groups. Dan. Med. Bull. 54, 306–369 (2007).

Erlangsen, A. et al. Short-term and long-term effects of psychosocial therapy for people after deliberate self-harm: a register-based, nationwide multicentre study using propensity score matching. Lancet Psychiatry 2, 49–58 (2015).

Fedyszyn, I. E., Erlangsen, A., Hjorthøj, C., Madsen, T. & Nordentoft, M. Repeated suicide attempts and suicide among individuals with a first emergency department contact for attempted suicide: a prospective, nationwide, Danish register-based study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 77, 832–840 (2016).

Runeson, B., Haglund, A., Lichtenstein, P. & Tidemalm, D. Suicide risk after nonfatal self-harm: a national cohort study, 2000-2008. J. Clin. Psychiatry 77, 240–246 (2016).

Perry, I. J. et al. The incidence and repetition of hospital-treated deliberate self harm: findings from the world’s first national registry. PLoS ONE 7, e31663 (2012).

Liu, B.-P. et al. Associating factors of suicide and repetition following self-harm: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. eClinicalMedicine 49, 101461 (2022).

Wiktorsson, S., Strömsten, L., Renberg, E. S., Runeson, B. & Waern, M. Clinical characteristics in older, middle-aged and young adults who present with suicide attempts at psychiatric emergency departments: a multisite study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 30, 342–351 (2022).

Beckman, K. et al. Method of self-harm in adolescents and young adults and risk of subsequent suicide. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 59, 948–956 (2018).

Birtwistle, J., Kelley, R., House, A. & Owens, D. Combination of self-harm methods and fatal and non-fatal repetition: a cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 218, 188–194 (2017).

Borges, G. et al. A meta-analysis of acute use of alcohol and the risk of suicide attempt. Psychol. Med. 47, 949–957 (2017).

Kõlves, K., Värnik, A., Tooding, L. M. & Wasserman, D. The role of alcohol in suicide: a case-control psychological autopsy study. Psychol. Med. 36, 923–930 (2006).

Demesmaeker, A., Chazard, E., Vaiva, G. & Amad, A. Risk factors for reattempt and suicide within 6 months after an attempt in the French ALGOS cohort: a survival tree analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 82, 20m13589 (2021).

Haukka, J., Suominen, K., Partonen, T. & Lonnqvist, J. Determinants and outcomes of serious attempted suicide: a nationwide study in Finland, 1996–2003. Am. J. Epidemiol. 167, 1155–1163 (2008).

Bergen, H. et al. Premature death after self-harm: a multicentre cohort study. Lancet 380, 1568–1574 (2012).

Salles, J. et al. Suicide attempts: how does the acute use of alcohol affect suicide intent? Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 50, 315–328 (2020).

Chen, I. M. et al. Risk factors of suicide mortality among multiple attempters: a national registry study in Taiwan. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 115, 364–371 (2016).

de la Torre-Luque, A. et al. Risk of suicide attempt repetition after an index attempt: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 81, 51–56 (2023).

Griffin, E., Kavalidou, K., Bonner, B., O’Hagan, D. & Corcoran, P. Risk of repetition and subsequent self-harm following presentation to hospital with suicidal ideation: a longitudinal registry study. EClinicalMedicine 23, 100378 (2020).

Ferguson, M., Rhodes, K., Loughhead, M., McIntyre, H. & Procter, N. The effectiveness of the safety planning intervention for adults experiencing suicide-related distress: a systematic review. Arch. Suicide Res. 26, 1022–1045 (2022).

Nuij, C. et al. Safety planning-type interventions for suicide prevention: meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 219, 419–426 (2021).

Dusetzina, S. B. et al. Linking Data for Health Services Research: A Framework and Instructional Guide (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2014).

Jokinen, J., Talbäck, M., Feychting, M., Ahlbom, A. & Ljung, R. Life expectancy after the first suicide attempt. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 137, 287–295 (2018).

Joyce, M. et al. National Self-Harm Registry Ireland Annual Report 2019 (National Suicide Research Foundation, 2020).

Schmidtke, A. et al. Attempted suicide in Europe: rates, trends and sociodemographic characteristics of suicide attempters during the period 1989–1992. Results of the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Parasuicide. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 93, 327–338 (1996).

Geulayov, G. et al. Epidemiology and trends in non-fatal self-harm in three centres in England, 2000–2012: findings from the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England. BMJ Open 6, e010538 (2016).

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research Vol. 2 (World Health Organisation, 1993).

Cox, G., Munnelly, A., Rochford, S. & Kavalidou, K. Irish Probable Suicide Deaths Study (IPSDS) 2015–2018 (HSE National Office for Suicide Prevention, 2022).

Lynn, E., Lyons, S., Walsh, S. & Long, J. Trends in Deaths Among Drug Users in Ireland from Traumatic and Medical Causes, 1998 to 2005 (Health Research Board, 2009).

Rosenberg, M. L. et al. Operational criteria for the determination of suicide. J. Forensic Sci. 33, 1445–1456 (1988).

Kielty, J. et al. Psychiatric and psycho-social characteristics of suicide completers: a comprehensive evaluation of psychiatric case records and postmortem findings. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 32, 167–176 (2015).

PEA11: Population Estimates from 1926 (Central Statistics Office, accessed 17 October 2022); http://data.cso.ie

Haase, T. & Pratschke, J. The 2016 Pobal HP Deprivation Index (Trutz Haase, accessed 17 October 2022); http://trutzhaase.eu/deprivation-index/the-2016-pobal-hp-deprivation-index-for-small-areas/

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Lyons and E. Lynn of the Health Research Board for their assistance with the data linkage process. We also thank G. Cox and members of the IPSDS Data and Intelligence Advisory Group for facilitating this work. E.G. is supported by an HRB Emerging Investigator Award (grant number EIA-2019-005). E.A. is supported by an HRB Research Leader Award (grant number IRRL-2015-1586). E.M.McM. is supported by an HRB Applying Research into Policy and Practice Award (grant number ARPP-A-2018-009). The study funders had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.G., E.M.McM., P.C., E.A. and I.J.P. were responsible for study conception and design. E.G. and P.C. conducted the data analysis. E.G., E.M.McM. and K.K. were responsible for data compilation and data cleaning. E.G. and E.M.McM. drafted the manuscript, which was reviewed by all authors. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Mental Health thanks Alejandro de la Torre-Luque and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Griffin, E., Corcoran, P., Arensman, E. et al. Suicide risk following hospital attendance with self-harm: a national cohort study in Ireland. Nat. Mental Health 1, 982–989 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-023-00153-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-023-00153-6