Abstract

Methods for identifying bacterial pathogens are broadly categorised into conventional culture-based microbiology, nucleic acid-based tests, and mass spectrometry. The conventional method requires several days to isolate and identify bacteria. Nucleic acid-based tests and mass spectrometry are relatively rapid and reliable, but they require trained technicians. Moreover, mass spectrometry requires expensive equipment. The development of a novel, inexpensive, and simple technique for identifying bacterial pathogens is needed. Through combining micropore technology and assembly machine learning, we developed a novel classifier whose receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve showed an area under the ROC curve of 0.94, which rapidly differentiated between Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis in this proof-of-concept study. Morphologically similar bacteria belonging to an identical genus can be distinguished using our method, which requires no specific training, and may facilitate the diagnosis and treatment of patients with bacterial infections in remote areas and in developing countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most important pathogens in humans, causing numerous infections ranging from furuncles to infective endocarditis1,2. S. aureus is a leading cause of nosocomial infections, such as catheter-related bloodstream infection, prosthetic joint infection, prosthetic valve endocarditis, and surgical site infection1,2. Another significant bacterium of the genus Staphylococcus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, is one of the most commonly found coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS) and is predominant in human skin microbiota3,4. It causes various nosocomial opportunistic infections, particularly those associated with indwelling devices5, similar to S. aureus in the sense that both bacteria causes internal medical device infection6,7. Generally, S. epidermidis is less virulent than S. aureus but can be critical, particularly in causing bacteremia8,9. When a blood culture is reported to be positive for Staphylococcus species preliminarily in the clinical setting, clinicians must immediately respond to two questions, namely, whether the bacteria is S. aureus or CNS and whether it is a contaminant10. However, there are no rapid and reliable bedside assessment tools to distinguish S. aureus from CNS bacteria.

Today, the three general direct bacterial identification methods are as follows: conventional culture-based microbiology; nucleic acid-based tests, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing; and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS)11,12. Despite being well-established, the conventional method has disadvantages. First, not all bacteria can grow in the laboratory and, even if they are culturable, it is unclear to what extent culture growth is dependant on the environment (e.g., temperature, atmosphere, and medium)13. Several days to weeks are required to grow, isolate, and identify bacteria. Nucleic acid-based tests and MALDI-TOF MS are relatively rapid and reliable. However, PCR requires primers designed for each targeted bacterium, and 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing requires a sequencer and database reference, with both methods taking several hours to days to complete. MALDI-TOF MS cannot be directly used in clinical samples or to distinguish several pathogens (e. g. Shigella spp. vs Escherichia coli14, Acinetobacter non-baumanii species15). Additionally, it requires expensive equipment. Culture methods and nucleic-acid-based tests require trained technicians. Therefore, it is necessary to establish a novel, rapid, inexpensive, and user-friendly technique for the identification of bacteria.

Micropore devices can be used for optical cell detection and counting16. Furthermore, machine learning is useful for predicting antimicrobial resistance in bacteria identified using other methods17. In our study, we developed a disposable single-use micropore module for bacterial detection. The module has a pore of 3 μm diameter on a silicon film with two flow channels and electrodes. This module is easily handleable because the flow channels automatically absorb sample fluids by capillary action and needs no special techniques. When a single particle (e. g. a bacterium) move through the micropore, we can detect the change of ionic current. This change of ionic current varies depending on the particles. The combination of nanopore or micropore technology and machine learning has enabled the rapid detection and identification of microorganisms18,19. Escherichia coli (gram-negative) has been previously distinguished from Bacillus subtilis (gram-positive)19, which are microbiologically different.

Here, in this proof-of-concept study, using a micropore-based device assisted with artificial intelligence (AI), we as a first step aimed to develop a simple method to rapidly distinguish morphologically similar S. aureus from S. epidermidis that belong to an identical genus, to demonstrate the usefulness of AI-assisted diagnosis in clinical microbiology.

Results

A micropore device

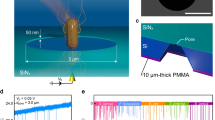

Micropores (3 µm in diameter) were fabricated on a 50 nm-thick silicon nitride film cast on a silicon substrate. The silicon substrate was sandwiched between a 25 mm × 25 mm 0.5-mm-thick plastic channel. This structure is termed “a micropore module” or “a module” (Fig. 1a, b). Bacterial suspensions (18 µL) in 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and PBS (15 µL) were introduced into the cis and trans chambers, respectively. We measured ionic current–time waveforms through applying a voltage of −0.1 V between the Ag/AgCl electrodes placed in the flow channel. When the bacteria passed through the micropores, the ionic current decreased owing to obstruction due to the flowing ions (Fig. 1c). S. aureus and S. epidermidis are spherical in shape with a diameter ranging from 0.6 to 1.0 µm under a low vacuum of 98 hPa. We observed no specific differences in the bacterial structures through scanning electron microscopy (SEM) under the culture conditions (Fig. 1d–g). The waveforms were collected in the data server and analysed, as described in the “Methods” section. The number of available waveforms for the bacterial suspensions was independent of their optical densities measured at a wavelength of 600 nm (OD600) (Fig. 1 h). Therefore, sufficient bacteria were present in the suspensions regardless of their OD600 values.

(a) The structure of the micropore module. The micropore module is 25 mm2 in size and 0.5 mm thick. The bacterial suspension is introduced from the cis channel, and PBS is introduced from the trans channel. (b) An optical image of the pore of the module. The optical microscopic examination of the micropore module suggests that the 3 μm diameter micropore is in the centre of the silicon substrate. (c) A schema of the micropore. When the bacteria pass through the micropore, the ionic current decreases because of obstruction in flowing ions. The processing software obtains the change in ionic current as a waveform. (d) Scanning electron microscope (SEM) observation of S. epidermidis ×14,000. (e) SEM observation of S. epidermidis ×60,000. (f) SEM observation of S. aureus ×14,000. (g) SEM observation of S. aureus ×60,000. (h) A scatter diagram of the OD600 of the bacterial suspensions and their average pulse counts. No correlations were observed between the OD600 and pulse counts of the bacterial suspensions.

Bacterial movement and ionic current

Ionic current measurements were performed on S. aureus and S. epidermidis cultures using micropore devices placed under an optical microscope. The base current was approximately 0.4 µA. Using the equations for access resistance (1/κD) and micropore resistance (4L/πκD2), the base current was estimated to be 0.5 nA when the ionic conductivity (κ) of 1× PBS was 1.61 Sm−1, the average diameter of the micropores was D = 3 µm, and the thickness of the micropores was L = 50 nm. The ionic current obtained was consistent with the theoretically estimated ionic current. With application of a voltage of −0.1 V, a single bacterium (black spot indicated by yellow arrow, Fig. 2a) was pulled into the micropore. Bacteria within an approximate radius of 15 µm from the micropore were pulled in at an accelerated rate as they approached the micropore (Fig. 2a \(\langle 1\rangle\)). When one bacterium passed through the micropore, we observed a single ionic current–time waveform, and the ionic current did not change until it entered the micropore. Bacteria within an approximate radius of 40 µm from the micropore were drawn to the micropore by Brownian motion (Fig. 2a\(\langle 2\rangle\)). The duration of Brownian motion was > 1 min while approaching the micropores. When a bacterium reached an approximate 15 µm radius from the micropore threshold, it was rapidly pulled into the micropore, which suggested it was being pulled under the influence of electric forces.

(a) Optical microscope images (scale bar = 10 µm) of S. epidermidis (small dot indicated by yellow arrow) being drawn towards and pulled into a micropore (3 µm black circles): <1> the bacterium near (within 15 µm radius) the micropore is pulled in at a fast rate; <2> the trajectory of a distant bacterium being drawn towards the micropore until it is pulled in. (b) Actual display screen during the measurement. The moment at which the bacteria (yellow arrow) is being sucked into the micropore. Its waveform is denoted on the right top column of the right-side window. The waveforms are indicated at three different time scales using the waveform viewer software.

Negatively charged bacteria were subjected to diffusion and electric forces between the electrodes. The radius (r) from the centre of the micropore at which the bacteria were trapped by the electric field is denoted by the equation:

where d, µ, and ΔV are the diameter of the micropore, the mobility of the bacteria, and applied voltage, respectively, and h and D are the thickness of the micropores and diffusion constant of the bacteria, respectively. The bacterial mobility and diffusion constants were approximately − 10−8 mV−1 s−1 and 10−9 m2 s−1, respectively. The experimentally observed r = 15 µm was relatively close to the theoretically predicted r = 22.5 µm. When the bacteria did not pass through the micropores, the ionic current remained constant at the base current, which was correlated with a non-event (Supplementary Material: the captured video of the actual screen during the measurement of the ionic currents of the bacteria. The optical microscopic image is shown on the left side, and the waveforms of ionic currents are shown on the right side). When a bacterium passed through the micropore, we obtained a spike-shaped ionic current–time waveform corresponding to one bacterium (Fig. 2b). The combination of optical microscopy and ionic current measurements demonstrated a correlation between the movement of a single bacterium and the ionic current–time waveform.

Creating the classifier

Spike-shaped waveforms are characterised by a maximum current value (Ip) and current duration (td) (Fig. 1c). The histograms of Ip and td nearly overlapped completely (Fig. 3a, b). Similar Ip levels reflected a small difference in the size between the two bacterial species. It was difficult to distinguish between them using these histograms. However, we observed differences in the shapes of the waveforms between the bacteria, suggesting distinguishable features (Fig. 3c). We used machine learning for identifying the waveform features such that the waveforms obtained could be used to identify the two species.

Fifty isolates of S. aureus and S. epidermidis were used for ionic current measurements. Each bacterial isolate was measured in triplicate using a micropore device, and each measurement lasted for 3 min. The 15,000 waveforms obtained from the measurements were provided as inputs for the machine-learning training set. The accuracy of differentiating between the two species in a single waveform was F-value = 0.59, which exceeded the F-value = 0.5 for random discrimination (Fig. 3d). In this single-waveform learning, it is determined which species each single waveform belongs to. The F-value is denoted by the harmonic mean of the sensitivity and precision, 2/(1/sensitivity + 1/precision), as follows:

For S. epidermidis, the confusion matrix yielded a sensitivity and precision of 9781/(9781 + 5219) = 0.65 and 9781/(9781 + 6968) = 0.58, respectively. This resulted in an F-value of 0.62. Similarly, the sensitivity and precision for S. aureus were 0.61 and 0.54, respectively, yielding an F-value of 0.57. The overall adopted F-value was the average of the F-values obtained for the two species. We determined the species-level accuracy of the bacterial identification on an isolate-by-isolate basis using machine learning. Of the 50 bacterial isolates, 25 were selected randomly as the training set for each species, respectively. We determined the training set yielding the highest F-value. Using the selected training set, we performed assembly learning to develop a classifier to determine whether a bacterial isolate belonged to S. aureus or S. epidermidis. In this assembly learning, single waveforms of one isolate/strain are treated as an aggregated data. Therefore, this assembly learning is an isolate/strain-focused learning. In contrast to the single-waveform learning, it is determined which species the aggregated data of each isolate/strain belongs to. In addition, the assembly machine learning uses the entire distribution of waveforms in each species, in addition to independent parameters (Ip, td, current vector, and time vector). The F-value was 0.93 (Fig. 3e).

Distinguishing bacterial pathogens

The classifiers created during the machine learning process were used to distinguish the remaining 25 bacterial isolates (Fig. 4a) and the additional ATCC standard strains. Each isolate was assessed by the classifier for three measurements, and two or three correct responses from the three trials were regarded as the final correct answers for the isolate or strain.

(a) Hold-out method. We employed a hold-out method for machine learning that splits data into the following two groups: a training dataset and a testing dataset. (b) Receiver operating characteristic curve of the classifier. (c) Characteristic distribution of the waveform. The pulse data are acquired 250,000 times per min. ‘Steps’ denote the number of data points acquired, ‘Height’ denotes the current value of the pulse, and ‘Peak ratio’ denotes the location of the peak of the pulse, when the left edge of the pulse is 0 and the right edge of the pulse is 1. (d) Zeta potential distribution of the bacteria. The dashed line denotes the median, and the dotted line denotes the quartiles. No statistically significant difference was noted between the two species.

The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) was 0.94 (> 0.9), demonstrating that the trained classifier could distinguish S. aureus from S. epidermidis at a high accuracy (Fig. 4b)20. The sensitivity and specificity for S. aureus detection were 96.4% and 80.8%, respectively, with an accuracy of 88.9% (Table 1). The positive agreement was 84.4%, and the negative agreement was 95.5% (Table 1).

Ionic current–time waveforms consist of information in relation to the size, shape, and surface charges of bacteria passing through the micropores. Micropore measurements demonstrated few statistically significant differences in the size and shape of S. aureus and S. epidermidis (Fig. 4c).

The Zeta potential affects the ionic current of the particles measured using the micropore device, and indicates the electrical charge of the surface layer of the particles21. Zeta potentials of the S. aureus and S. epidermidis isolates were measured using a Zetasizer™ (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK)22. The surface charges of the two species indicated that they were negatively charged, with Zeta potentials > −20 mV. While the Zeta potential range of S. epidermidis was greater than that of S. aureus and the distribution pattern was not completely the same, there were no significant difference between the Zeta potentials of S. aureus and S. epidermidis (Fig. 4d). Machine learning used surface charge differences between the two bacteria to distinguish between the species in reference to the entire distribution pattern of the features, of which difference is too subtle to statistically detect. The ion current–time waveform provides information on the volume, structure, and surface charge of bacteria passing through micropores. The machine learning, which inputs the shape of the ion current–time waveform as a feature, is considered to distinguish differences in surface charge.

Discussion

The development of this bacterial identification technology, which combines micropore devices and machine learning, is a significant breakthrough because it is independent of biochemistry, molecular biology, and mass spectrometry. Bacteriologically distinct species have been previously distinguished using this method19. Herein, bacteria, namely S. aureus and S. epidermidis, belonging to an identical genus, could be distinguished using a combination of improved micropore devices and the assembly machine learning that used the entire set of features in each dataset, in addition to the classical parameters. This technique has three major benefits, as follows: rapidness, high accuracy, and low cost. First, the classifier required only a few seconds to identify the bacteria. Second, the AUROC was 0.94, the sensitivity for distinguishing S. aureus from S. epidermidis was 96.4%, the positive agreement was 84.4%, and the negative agreements was 95.5%, which highlights the usefulness of applying this technology to clinical medicine. From the viewpoint of antimicrobial stewardship, the rapid identification of infecting bacteria facilitates immediate administration of appropriate narrow spectrum antibiotics for infected patients. This is likely to help overcome antimicrobial resistance, which is a considerable threat to public health worldwide23. Third, this is a low-cost technique with respect to device and training operators. After mass production of the modules and detectors, the total running cost was estimated to be a few dollars per examination. The application of fluid samples to the module is simple because the fluid automatically fills the flow channel by capillary action. Therefore, operators can use the device without requiring special training.

A limitation of this study was that relatively few isolates were used for the dataset. However, we used 50 clinical isolates of S. aureus and S. epidermidis with 175,878 waveforms to develop the classifier. Moreover, the testing dataset included 50 clinical isolates and ATCC standard strains. We intend to gather more isolates to increase accuracy. Additionally, an adequate number of bacteria is required to create high-performance classifiers. This requirement can be a barrier in the development of classifiers using clinical samples with low numbers of bacteria. Furthermore, it is difficult to determine which feature AI predominantly focusses on during decision making. The cell wall anchored proteins of S. aureus and S. epidermidis is reported to be different24,25, so the manipulation of cell wall anchored proteins can be the target of further investigation to clarify the key features. In this study, it is certain that the AI considers the entire dataset of features. The assembly machine learning treats each bundle of waveforms derived from one strain as an aggregated data and utilizes the whole distribution of the strain-based dataset. More sophisticated generalization ability of the AI can be achieved through gathering a greater number of multiple datasets and through improving the AI program.

In conclusion, we developed a novel micropore device combined with machine learning that can distinguish S. aureus from S. epidermidis with a high sensitivity of 96.4%, independent of existing microbiological identification measures. This technique in which micropore devices and machine learning were combined can significantly contribute to the diagnosis and treatment of bacterial infectious diseases. This development is important, given that it is extremely challenging to create novel classifiers that can widen the range of applications to other types of microorganisms or specimens (e.g., blood, urine, pus, and sputum). Furthermore, ongoing improvement of modules and detectors is likely to help in detecting more subtle differences in the surface structure of bacteria. Our present study is the first step for differentiating clinically isolated bacteria, which leads to the broader approach to other bacterial pathogens and other culture conditions. This micropore-AI combined method can be used as a one-stop bedside platform, to help identify microorganisms from various specimens and their antimicrobial resistance using the internet and the cloud AI system (Fig. 5). Regarding its clinical applications, it is likely that the number of species able to be distinguished and its capability for antibiotic resistance detection will improve.

Methods

Preparation of cultured bacteria

We used 50 clinical isolates of S. epidermidis, 25 clinical isolates of methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA), and 25 clinical isolates of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), which were clinically isolated and identified in the laboratory. Methicillin resistance was confirmed by the growth on BD BBL ™ CHROMagar ™ MRSA II Agar Medium (Becton, Dickinson and Company, NJ, USA) and PCR for mecA as described by Okuma et al26. For differentiating between S. aureus and S. epidermidis, we used additional ATCC standard strains: ATCC 6538 for MSSA, LAC (USA300, ATCC BAA-1756) and MW2 (ATCC BAA-1707) for MRSA, ATCC 12228 for S. epidermidis.

All the isolates and strains were grown in Trypticase Soy broth (Becton, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). After overnight incubation at 37 °C, the bacterial cells were washed and diluted in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), with an optical density between approximately 0.1 and 0.3 at 600 nm (OD600) to avoid clogging of the pores.

Scanning electron microscopy

We used a JSM-7900F Schottky Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) for the SEM observation of the bacteria.

The bacterial suspensions were prepared for SEM observation according to Rusu et al.’s27 previously described protocol, which was modified for our low-vacuum SEM. Briefly, the suspensions were washed three times with PBS. We centrifuged 200 μL of each aliquot at 6000 rpm for 5 min and fixed the pellets with 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution overnight. After fixation, each aliquot was washed three times with distilled water. Subsequently, 10 μL of each aliquot was mounted on a Si wafer and desiccated in a series of ethanol solutions (50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 95%, and 99.5% for 3 times). After overnight desiccation, we performed SEM analysis. All observations were performed at a pressure of 98 hPa with a 10.0 kV accelerating voltage using a low-vacuum backscatter electron detector.

Fabrication of micropore modules

A 50-nm- thick SiN film was deposited on both sides of a 0.5-mm- thick silicon wafer by low pressure chemical vapor deposition (LPCVD). SiO2 of 300-nm thickness was deposited on top of the SiN film by CVD. Holes with a diameter of 3 mm were drawn by photolithography. SiO2 and SiN were etched using reactive ion etching to fabricate micropores. A 1 mm × 1 mm square was drawn on the backside by photolithography. The SiO2 and SiN on the backside were then etched using reactive ion etching. Next, Si was etched using KOH. Finally, SiO2 was etched with a mixture of HF and NH4F. Plastic channels (25 mm × 25 mm × 0.2 mm) were fabricated using polydimethylsiloxane. The Ag/AgCl electrodes were fabricated in the channel.

Resistive pulse measurements

We obtained micropore-based ionic current–time waveform measurements using a microSCOUTER1200TM (Advantest Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) instrument at a sampling rate of 250 kHz with a 100-kHz low-pass filter. The bacterial solution and 1× PBS buffer solution were placed in the cis- and trans-side chambers, respectively. The micropores were placed in a special socket, which was then transferred to a measurement device for measurements. A micropore module (base current = 10 nA) was used to measure the bacterial features. To avoid contamination, a micropore module was used for each measurement and disposed of.

Optical microscopy

An Olympus DSX-1000 optical microscope (Evident Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was used to capture bacterial movement. A 20× objective lens with 2800× optical zoom was used to observe bacteria in the micropore module. A polarimetric method was used for the observation, and videos were captured at a frame rate of 30 frames per second. A handcrafted fixture was mounted on an optical microscope stage for seating the microSCOUTER 1200™ instrument.

Machine learning

The ionic current–time waveforms obtained were extracted using commercially available Aipore-PC software (Aipore Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and transferred to the Aipore-OneTM (Aipore Inc.) server. Machine learning was performed using the server. The features were generated using tsfresh. Specifically, the ion current–time waveform was represented by an N-divided vector in the vertical direction and an M-divided vector in the horizontal direction. As classifiers, we selected the open-source “scikit-learn” classifier and LightGBM. The effects of imbalance in the number of data were prevented using an undersampling method that adjusts the number of data to match the smallest number of data. Classifier training was performed on the combination of generated features and classifiers. The machine learning program outputs the F-value, an accuracy measure that can distinguish between two bacteria in a single waveform. The “trained” classifier with the most accurate combination of features and classifiers then identified a particular bacterium belonging to one of two species. The accuracy was assessed through a tenfold cross-validation process. Aipore-ONE™ automatically generates and displays a confusion matrix that assigns one waveform to each bacterial species. The bacteria were then identified on a strain-by-strain basis. Several ion current–time waveforms were obtained by measuring a single strain. Using the classifier and features obtaining the highest accuracy for one ion current–time waveform, the identification results of all ion current–time waveforms obtained during the three-minute measurement were assembled to create a classifier for single strain identification. The single strain classifier was then employed for strain-by-strain testing. Strain-by-strain identification was also performed using Aipore-ONE™.

Surface charge measurements

The surface charges of the bacteria were measured using a Zetasizer™ (Malvern Instruments, UK). 10 isolates of the S. aureus and 10 isolates of the S. epidermidis were tested. The bacterial solutions were diluted 100-fold in ultrapure water and placed in standard cells. We performed the measurements for five times per bacterial solution for 120 s at 25 °C. The zeta potentials obtained were statistically assessed using a linear mixed-effects model.

Statistical analyses

We used the linear mixed-effects model to compare the zeta potentials between S. aureus and S. epidermidis. All the data measured above were analyzed. We have considered strain level as random effects in the model.

Data availability

The measurement data of the current–time profile of bacteria obtained in this study are available on Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7882378 and https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10547661).

References

Cheung, G. Y. C., Bae, J. S. & Otto, M. Pathogenicity and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus. Virulence 12, 547–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2021.1878688 (2021).

Lee, A. S. et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 4, 18033. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2018.33 (2018).

Byrd, A. L., Belkaid, Y. & Segre, J. A. The human skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.157 (2018).

Severn, M. M. & Horswill, A. R. Staphylococcus epidermidis and its dual lifestyle in skin health and infection. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-022-00780-3 (2023).

Otto, M. Staphylococcus epidermidis—The “accidental” pathogen. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 555–567. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2182 (2009).

Otto, M. Staphylococcal biofilms. Microbiol. Spectr. 6, 4. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0023-2018 (2018).

Oliveira, W. F. et al. Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis infections on implants. J. Hosp. Infect. 98(2), 111–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2017.11.008 (2018).

Osaki, S. et al. Distinguishing coagulase-negative Staphylococcus bacteremia from contamination using blood-culture positive bottle detection pattern and time to positivity. J. Infect. Chemother. 26, 672–675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiac.2020.02.004 (2020).

Tak, V., Mathur, P., Lalwani, S. & Misra, M. C. Staphylococcal blood stream infections: Epidemiology, resistance pattern and outcome at a level 1 Indian trauma care center. J. Lab. Phys. 5, 46–50. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-2727.115939 (2013).

Weinstein, M. P. Blood culture contamination: Persisting problems and partial progress. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41, 2275–2278. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.41.6.2275-2278.2003 (2003).

Clarridge, J. E. Impact of 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis for identification of bacteria on clinical microbiology and infectious diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17, 840–862. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.17.4.840-862.2004 (2004).

Bizzini, A. & Greub, G. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry, a revolution in clinical microbial identification. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16, 1614–1619. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03311.x (2010).

Austin, B. The value of cultures to modern microbiology. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 110, 1247–1256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10482-017-0840-8 (2017).

van den Beld, M. J. C., Rossen, J. W. A., Evers, N., Kooistra-Smid, M. A. M. D. & Reubsaet, F. A. G. MALDI-TOF MS using a custom-made database, biomarker assignment, or mathematical classifiers does not differentiate Shigella spp. and Escherichia coli. Microorganisms 10, 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10020435 (2022).

Sheck, E. et al. Acinetobacter non-baumannii species: Occurrence in infections in hospitalized patients, identification, and antibiotic resistance. Antibiotics (Basel) 12(8), 1301. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12081301 (2023).

Olmos, C. M. et al. Hybrid microchannel-solid state micropore device for fast and optical cell detection. RSC Adv. 10, 5361–5370. https://doi.org/10.1039/c9ra09939e (2020).

Weis, C. et al. Direct antimicrobial resistance prediction from clinical MALDI-TOF mass spectra using machine learning. Nat. Med. 28, 164–174. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01619-9 (2022).

Taniguchi, M. et al. Combining machine learning and nanopore construction creates an artificial intelligence nanopore for coronavirus detection. Nat. Commun. 12, 3726. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24001-2 (2021).

Tsutsui, M. et al. Discriminating single-bacterial shape using low-aspect-ratio pores. Sci. Rep. 7, 17371. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17443-6 (2017).

Akobeng, A. K. Understanding diagnostic tests 3: Receiver operating characteristic curves. Acta Paediatr. 96, 644–647. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.00178.x (2007).

Clogston, J. D. & Patri, A. K. Zeta potential measurement. Methods Mol. Biol. 697, 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-60327-198-1_6 (2011).

Kłodzińska, E. et al. Differentiation of Staphylococcus aureus strains by CE, zeta potential and coagulase gene polymorphism. Electrophoresis 30, 3086–3091. https://doi.org/10.1002/elps.200900186 (2009).

European Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. The burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in the WHO European region in 2019: A cross-country systematic analysis. Lancet Public Health 7, e897–e913. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00225-0 (2022).

Foster, T. J. Surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol. Spectr. 7, 4. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0046-2018 (2019).

Foster, T. J. Surface proteins of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Front. Microbiol. 11, 1829. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01829 (2020).

Okuma, K. et al. Dissemination of new methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in the community. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40(11), 4289–4294. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.40.11.4289-4294.2002 (2002).

Rusu, D. et al. A qualitative and semiquantitative SEM study of the morphology of the biofilm on root surfaces of human teeth with endodontic-periodontal lesions. Exp. Ther. Med. 20, 201. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2020.9331 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Yumi Matsuoka-Nakamura for providing the LAC (USA 300, ATCC BAA-1756) and MW2 (ATCC BAA-1707) strains with us. We thank Dr. Isao Nishi for providing the clinical bacterial isolates with us. We thank Ms. Tomoko Nakada for assisting the measurement of zeta potentials of the bacteria. We thank Ms. Sanae Murayama for assisting the SEM observation of the bacteria. This research was conducted as part of the All-Osaka U Research in "The Nippon Foundation—Osaka University Infectious Disease Response Project".

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M. conducted the bacterial experiments and wrote the manuscript. M.T. conceived the technology, supervised the project, and wrote the manuscript. H.T. conducted the bacterial observation and supported the bacterial experiments. O.S. developed the software for machine learning. N.N. and J.Y. supported the bacterial experiments. Y.A., K.T., S.K. and S.H. supervised the project. D.O. conducted statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M. T., O. S. and N. N. are the co-founders of Aipore Co., Ltd., and its Director and Chief Executive Officer, respectively. All authors, other than M. T., O. S. and N. N., have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Video 1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Morimura, A., Taniguchi, M., Takei, H. et al. Using novel micropore technology combined with artificial intelligence to differentiate Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Sci Rep 14, 6994 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55773-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55773-4

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.