Abstract

Copper corrosion in acidic cleaning solutions is a major worry for heat exchangers. Corrosion inhibitors derived from natural sources might be a viable option. The isolation of Oleuropein compound from olive leaf and investigation of its anticorrosion potential for copper in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution are reported here. All experimental results from LC–MS, FT-IR, 1H and 13C-NMR characterizations support the molecular structure of Oleuropein. Electrochemical and gravimetric tests were used to evaluate the corrosion inhibition capabilities of Oleuropein. According to polarization investigation, Oleuropein is a mixed-type inhibitor. Oleuropein's inhibitory efficacy increases with concentration, attaining an optimum value (98.92%) at 100 mg L−1. At high temperatures, Oleuropein can be considered an efficient inhibitor. Thermodynamic variables for the activation operation and copper dissolution were computed and addressed as well. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) examinations revealed that Oleuropein produced an outer layer on the copper surface, shielding it from severe acid damage. Quantum chemical simulations were employed to propose molecular explanations for Oleuropein's inhibitory actions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heat exchangers made of copper metal and alloys are essential components for the thermal desalination sector, whether for desalting or heat restoration objectives to boost thermal performance1. The majority of industrial heat exchangers directly interact with a saltwater cooling solution, which causes scaling2. The need to disconnect machines for acid cleaning, which is usually dependent on acids, mandates a suitable method with careful control3,4. Acid cleaning procedures are utilized for de-scaling and the accompanying base metal preservation. Sulfuric acid treatment is commonly employed in the metals cleaning procedure to remove dust and scale from the base metal5,6.

The many corrosion problems that might occur during acid cleaning can lead to the breakdown of copper alloy heat exchanger7,8. Adding corrosion inhibitors into acid solutions is a cost-effective and efficient strategy to keep metals from corroding9,10,11,12. Organic corrosion inhibitors are widely utilized because of their inexpensive cost and high corrosion resistance. Luo et al.13 produced and developed a novel type of pyridazine-based compound as a copper corrosion inhibitor in 0.5 M sulphuric acid. At 298 K, this inhibitor has a maximal inhibitory effectiveness of 94.1%. Laggoun et al.14 investigated the inhibitory influences of p-toluenesulfonylhydrazide on copper corrosion in acid solution, demonstrating that it has a maximum anti-corrosion performance of greater than 90%. Many widely used organic corrosion inhibitors, on the other hand, have complicated synthesis procedures, severe toxicity, and are susceptible to pollution problems.

The approach of investigating aqueous extracts as corrosion inhibitors has a significant benefit. The key properties that enable the extracts to be the most successful recent the corrosion inhibitors categories are its nontoxicity, ecologically benign attitude, as well as the feature that they are affordable and sustainable. Previous research by Oukhrib et al.15 employed natural plant extracts including saffron extract as a copper corrosion inhibitor in the saltwater surrounding, with an inhibitory efficacy of 84% using 2 g/L. Jmia et al.16 investigated the inhibition activity of jujube pulp extract on copper corrode in 1 M HCl solution. The findings confirmed that the inhibition gradually increases with the amount of jujube pulp extract, achieving a highest of 93% at a dosage of 1 g/L.

In general, most extracts employed as corrosion inhibitors include a high concentration of organic components. The inhibitory activities of these extracts are caused by the total of the extract's constituents. The isolation of Oleuropein from olive leaf extract and analysis of its anticorrosion activity for copper in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution is a new trend in this work. In addition to theoretical research, we utilized chemical, electrochemical, and surface experiments to investigate Oleuropein's anticorrosion capabilities.

Experimental part

Materials

Copper samples with a purity of 98% were used in this investigation. Prior to testing, the copper sample was sanded by succession of emery papers (ranging from 600.0 to 1200.0 grades) and then cleaned with purified water and ethyl alcohol.

For all investigations, 1.0 M H2SO4 solutions were prepared using analar grade H2SO4 (Merck) and deionized water.

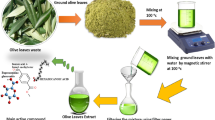

Extraction, purification and characterization of Oleuropein from Olea europaea leaves

In the current work, the corrosion inhibition is caused by pure Oleuropein. The process for isolating and purifying Oleuropein from the extract's components was demonstrated in the next section.

50 g of freshly picked olive leaves (Olea europaea L.) were cut into small pieces that were gently boiled for 2 h in a 1 L beaker containing distilled water by using a mass ratio 1:10 (leaves/water). 250 mL of decoction, cooled at room temperature, were extracted with 50 mL of chloroform for three times, adding NaCl salt to facilitate the breaking of the emulsion. Pure Oleuropein was isolated extracting the aqueous phase with three aliquots of 50 mL of ethyl ethanoate. The organic fractions were collected, dehydrated with anhydrous sodium sulphate and then filtered. After the solvent evaporation under vacuum, 1.09 g of a sticky solid was obtained. A sample of the obtained sticky solid residue was dissolved in acetonitrile, then filtered and examined by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (Agilent 1100 series, USA).

The qualitative evaluations were performed using (6540) quadrupole-time-of-flight (QTOF) mass analyzer equipped with electro-spray-ionization (ESI) device. FTIR analysis was taken using Jasco/FTIR/430 spectrometer fitted with an ATR crystal sampler.

1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra were acquired at ambient temperature in CD3OD using NMR spectrometer (Bruker Avance 400), and chemical shifts have been presented respect to TMS.

We confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Electrochemical experiments

A potentiostat/galvanostat/Gamry-model 3000 was used for the electrochemical experiments. The experiments were implemented out in a multiple cell, with a copper disc serving as the working part (having an effective surface area of 0.545 cm2), a Pt strip serving as the counter part, and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as the reference part. Varying potential ranges (± 250 mV/SCE vs. OCP) were applied to the copper electrode using 1.0 mV s−1 scan rate to produce the Tafel polarization plots. The results for electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were taken at OCP at amplitude of 20 mV within a frequency region 100 kHz–0.1 Hz. To confirm the correctness of the electrochemical experiments, they were performed three times.

Gravimetric experiments

To evaluate gravimetric measures, copper plates were sliced into 2.5 cm × 1.2 cm × 0.05 cm pieces (the average weight = 1.4534 g). The copper plates were submerged in 100 mL of either 1.0 M H2SO4 or Oleuropein-treated H2SO4 solutions. The gravimetric was calculated using the standard method G1-03-2017-e1 ASTM17. For 24 h, the samples were submerged in solutions. The trials were carried out in three replicate, and the mean mass loss was determined. Numerous experiments at various temperatures (298, 313, 323, and 333 K) utilizing a temperature-controlled water bath were planned.

Surface morphology analysis

SEM (JEOL JEM-1200EX) combined with energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry was employed to inspect the surface aspect of a copper plate submerged in experiment liquids for 24 h.

Theoretical considerations

To study the interaction activities of Oleuropein, quantum chemical simulations based on the DFT approach were done. Geometry optimization was performed utilizing VAMP configuration of Accelrys Inc.'s Materials Studio-6.0.

Results and discussion

Oleuropein characterizations

The Oleuropein used in this work has been characterized giving analytical and spectral data. The HPLC–DAD chromatogram of purified sample and its ESI–MS profile are shown in Fig. 1. The existence of a molecular ion (m/z 539) and a fragment deriving from the decline of the sugar molecule, matching to the aglycon (m/z 377) is confirmed by the mass spectrum.

The FT-IR spectrum performed for Oleuropein extract was seen in Fig. 2. The OH stretching vibrations cause a wide band (3700–3100 cm−1). C–H stretching bands appear at 2926 and 2856 cm−1. The 1750–1500 cm−1 area correlates directly to stretching vibrations of C=O and C=C. In the complex region of 1500–1200 cm−1 appears the C–O stretching that produces an absorption band 1262 cm−1.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ = 7.51 (s, 1H, s), 6.85–6.67 (m, 2H), 6.54–6.50 (m, 1H), 6.08 (1H, m), 5.91 (br. S, 1H), 4.22 (m, 2H, m), 4.00 (m, 2H, m), 3.73 (s, 3H, s), 3.67–3.30 (m), 2.80–2.40 (4H, m), 1.66 (3H, d, J = 7.1 Hz) ppm.

13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD): δ = 172.35, 167.75, 154.24, 145.20, 143.87, 130.80, 129.78, 123.97, 120.39, 116.12, 115.07, 108.34, 99.88, 94.23, 77.35, 76.88, 73.73, 70.44, 66.00, 61.70, 51.06, 40.29, 34.37, 30.81, 12.63 ppm.

All the experimental data related with the characterization LC–MS, FT-IR, 1H and 13C-NMR related with the Oleuropein used in this work are in agreement with the literature18,19.

Polarization and EIS measurements

At 298 K, Tafel polarization plot for copper in 1.0 M H2SO4 in the presence of varying concentration levels of Oleuropein is provided in Fig. 3. The polarization evaluation showed that increasing the quantity of Oleuropein alters both the cathodic and anodic current.

Tafel plot revealed the presence of corrosion breakdown potential at almost + 75 mV due to passivity breakdown20. The observed critical breakdown potential of copper increases as the concentration of Oleuropein increases. The Tafel polarization data are provided in Table 1. The change in corrosion potential (Ecorr) readings shows no recognizable sequence. The gap in Ecorr value for both blank acid solution and acid solution containing the Oleuropein seemed to be less than 85 mV, supporting the Oleuropein's mixed type behavior21,22. By increasing the concentration of Oleuropein, the Ecorr value moved also towards the negative direction. This change is caused by a decrease in the hydrogen evolution process on the copper surface resulting from Oleuropein molecule adsorption23. There have been no notable changes in the cathodic Tafel slop (βc) and anodic Tafel slop (βa) were detected, showing that adding Oleuropein to the corrosion environment had no effect on the mechanism of the anodic and cathodic processes. In the presence of Oleuropein, the corrosion current density (jcorr) values reveal a significant decrease (jcorr = 31.54 μA cm−2 for blank and 0.34 μA cm−2 for Oleuropein 100 mg L−1). This implies that Oleuropein suppresses copper electrode corrosion in 1.0 M H2SO4 solutions24. The inhibition ability of Oleuropein (ηj%) was quantified utilizing the formula below25,26:

where jcorr(0) denotes the corrosion current densities measured in an acid solution without Oleuropein.

Oleuropein's inhibition ability goes up with concentration, achieving a maximum output (98.92%) at 100 mg L−1 with surface coverage (\(\theta = 1 - \frac{{j_{{{\text{corr}}}} }}{{j_{{{\text{corr}}(0)}} }}\)) reaches to 0.9892. These data corroborate that Oleuropein has a strong inhibitory effect on copper corrosion in 1.0 M H2SO4.

The resultant Nyquist, phase angle and modulus plots can be illustrated in Fig. 4a–c, respectively. The equivalent circuit designed to estimate impedance behavior can also be seen in Fig. 4d. The generated impedance plots (Fig. 4a) exhibit flattened shapes (loop capacitive) that correlate to charge transfer27,28. The uniformity and surface topography of the copper surface cause this loop capacitive depression29. The radius of the capacitive loop grew in ways consistent with the amount of Oleuropein. The creation of an Oleuropein layer prevents the production of the corrosion product30,31. The addition of Oleuropein causes the phase angle values (Fig. 4b) to increase, resulting from the creation of a thicker protective layer. The EIS variables derived after fitting the curves in the equivalent circuit are summarized in Table 2. The charge transfer resistance (Rct) increases while the double layer capacitance (Cdl) magnitude drops when the concentration of Oleuropein increases. The increase in Rct value, which reaches a value of 12,000 cm2 at a concentration of 100 mg L−1, is predominantly due to Oleuropein adsorption on the copper surface32,33,34. When the concentration of Oleuropein inside the acid solution was increased, the value of the Cdl decreases to 1.33 × 10–6 F cm−2 as particularly in comparison to the blank value of 5.99 × 10–5 F cm−2 attributable to the restricted accessibility of charged particles towards the surface35. The inhibition ability of Oleuropein (ηR%) was quantified utilizing the formula below36:

where Rcto denotes the charge transfer resistance measured without Oleuropein. The inhibitory effectiveness rises with the concentration of Oleuropein, reaching a maximum (98.35%) at 100 mg L−1. This means that Oleuropein molecules are adsorbed at the copper/solution interface, delaying the oxidation reaction.

Gravimetric measurements

The mass loss approach is a non-electrochemical that represents dipping copper pieces in 1.0 M H2SO4 for an extended duration of time. The corrosion rate (CR) was evaluated using the next expression37:

A = copper piece surface area (cm2), t = duration (h), W = mass loss (mg).

The inhibition ability of Oleuropein (ηW%) was quantified utilizing the formula below37:

where CR0 denotes the corrosion rate measured in an acid solution without Oleuropein. Table 3 summarizes the CR and ηW% at various Oleuropein concentrations. The value of CR continues to decrease as the amount of Oleuropein increases. This reduction in CR with increasing Oleuropein concentration reflects an increasing trend in surface covering on the copper via Oleuropein molecules. For a concentration of 100 mg L−1 of Oleuropein, the highest inhibitory effectiveness (ηW% = 96.20) was found.

Temperature effects and thermodynamic analysis

Temperature is an important factor in the research of the corrosion mechanism in broad sense. Also, because rising temperatures have an impact on the interaction between the solution and the metal38,39. This allows us to evaluate the manner of the Oleuropein's adsorption on the copper surface and determine the Oleuropein's stability as the temperature rises. Table 4 illustrates the corrosion rate and inhibition capacity for Cu in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution with and without Oleuropein (100 mg L−1) as a function of temperature (298–333 K). The data show that the CR of copper in acid solution (either controlled or inhibited) tends to increase as temperature rises. This trend may be understood by the rough of the surface of the copper caused by the elevated temperature, as well as a switch in the adsorption/desorption balance toward desorption of Oleuropein from the copper surface40. The ηW% steadily drops as temperature rises (Table 4), indicating a physisorption process41. Because rising temperatures have little effect on ηW%, this signifies that the Oleuropein/surface system is stable at high temperature levels. Particularly at high temperature, Oleuropein can be regarded as an effective inhibitor.

The examination of the CR charting as a temperature—dependent allowed for the estimation of different variables including the activation energy (Ea), enthalpy change (ΔH*), and entropy change (ΔS*) to describe the oxidation operation and the likely mechanism of inhibitor adsorption. The Arrhenius plot (Fig. 5a) was used for evaluating the Ea in the presence/absence of Oleuropein (100 mg L−1), utilizing the below formula42:

R = molar gas constant, T = Kelvin temperature and A = pre-exponential constant.

The inclusion of Oleuropein raises the Ea from 10.64 kJ mol−1 (blank solution) to 38.79 kJ mol−1 (100 mg L−1 Oleuropein). Copper corrosion is slowed by high activation energy in the presence of Oleuropein. The adsorption of Oleuropein on the surface of copper causes a rise in the width of the double layer, which raises the energy barrier necessary to initiate the corrosion reaction. This was linked to the favorable physical sorption of Oleuropein molecules12.

The transition state equation and plot (Fig. 5b) was used to derive the values of ΔH* and ΔS*:

N = 6.2022 × 1023 mol−1 and h = 6.6261 × 10−34 m2 kg s−1.

The inclusion of Oleuropein raises the ΔH* from 8.02 kJ mol−1 (blank solution) to 36.18 kJ mol−1 (100 mg L−1 Oleuropein). The endothermic character of copper oxidation in acid solution can be seen from the positive magnitude of ΔH*43. The ΔS* varied to a slight extent from − 186.86 (blank solution) to − 119.66 J mol−1 K−1 (100 mg L−1 Oleuropein). Besides that, the moving from a negative value in case of blank solution to a less negative value of ΔS* in the case of the solution containing 100 mg L−1 Oleuropein could be likened to the freedom of a considerable portion of some more dis-ordered H2O molecules which have been adsorbed on the copper surface and are being replaced by more ordered Oleuropein molecules44.

The Langmuir isotherm model (Eq. 7) is mostly used to verify adsorption for this system45.

Cinh = Oleuropein concentration and Kads = equilibrium constant.

Figure 6 illustrates the Langmuir isotherm for Oleuropein. The correlation coefficients (R2) in Fig. 6 are much closer to one (i.e. 0.9997), demonstrating that this approach is acceptable for determining adsorption ability46. Importantly, the minimum Kads value (i.e. 0.0806 L mg-1) reflects Oleuropein's physical adsorption features. The Gibbs free energy (∆Gads°) of an adsorption system is calculated as follows47:

∆Gads° has a value of − 36.3 kJ mol−1, indicating that Oleuropein adsorption is mostly a physisorption mechanism47.

SEM/EDX analysis

To support the data of the electrochemical and gravimetric tests, observational microscopic SEM investigations were combined with quantification EDX analysis. A SEM top photo of the surface of copper in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution without Oleuropein is shown in Fig. 7a, and it can be seen that the uneven corrosion of the entire copper surface is very dense and clear. The EDX examination for the blank solution (Fig. 7b) revealed the existence of Cu and O signals, which are corrosive elements for copper oxide and so support the corrosion of copper. The addition of 100 mg L−1 of Oleuropein to 1.0 M H2SO4 solution reduces the corrosion extent on the copper surface and forms a nonuniform covering layer on the copper surface, as seen in the SEM picture (Fig. 8a). The appearance of C and O signals in the EDX spectra, which represent the primary constituents of Oleuropein molecule, is also shown in Fig. 8b. These findings demonstrate the creation of a protective layer when the tested Oleuropein interacts with the copper surface in acidic media.

Mechanism and theoretical considerations

The dissolving of copper in acidic media was carried out in the following stages48,49:

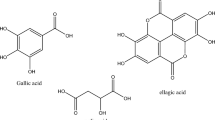

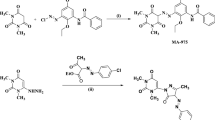

The barrier protection copper oxide layers may be quickly solubilized at low pH values, based on the potential–pH chart50. The various findings (SEM/EDX) demonstrate that the adsorption of the Oleuropein molecule on the copper surface is the primary mechanism of corrosion prevention. At the surface of copper, the Oleuropein molecule comprises O-bearing hydroxyl groups (see Fig. 9) which possess a great affinity for Cu. In parallel to the attachment of aromatic rings, physisorption on the copper surface results through partial transfers of O electrons and the creation of double bonds (see Fig. 10). The Oleuropein compound adsorbed film functions as a shield between both copper surface and the acidic corrosive liquid51,52,53. Another mechanism that may be included is the creation of Cu(I)-Oleuropein complexes on the copper surface. This complex suppresses the anodic process54.

To determine the molecular activity of Oleuropein, quantum chemical simulations based on the DFT model were carried out. As a consequence, the chemical characteristics of Oleuropein can be seen in Fig. 11. Figure 11a depicts the whole optimized geometrical arrangement of Oleuropein. The HOMO orbital reflects the molecule's electron-donating ability (Fig. 11b), whereas the LUMO orbital reflects the molecule's electron-acquiring ability (Fig. 11c)55. The HOMO and LUMO electron clouds for Oleuropein are generally observed to be virtually entirely centred in aromatic ring groups and OH groups. This reveals that all these active adsorption groups may exchange electrons with copper to create covalent connections. Oleuropein has a dipole moment (μ) of 13.67 debye. Adsorption on the metal surface increases as a result of the high dipole moment56. The high HOMO energy value (EHOMO = − 6.654 eV) draws attention to the capacity of the Oleuropein molecule to associate with the copper surface. Furthermore, the low LUMO energy (ELUMO = − 3.577 eV) alludes to the capacity of the Oleuropein molecule to receive electrons from the copper surface. Additionally, the low energy difference (ΔE = ELUMO − EHOMO, 3.077 eV) correlates to Oleuropein's good inhibitory performance57.

Oleuropein's electronegativity (χ) and global hardness (η) properties are computed using the following relationships58:

I = ionization potential = − EHOMO, A electron affinity = − ELUMO.

5.115 eV and 1.538 eV are the estimated values for χ and η, respectively.

Oleuropein molecules with a high χ value have a strong capacity to capture electrons and, as a consequence, have a high adsorption capacity. Besides that, the small η value for Oleuropein molecules shows that the surface copper and the inhibitor Oleuropein have a strong interaction59.

The number of electrons transmitted (ΔN) was also computed using the following formula:

χcu = 4.48 eV, ηcu = 0 eV for copper60.

The inhibitory effectiveness improved with increasing electron-donating capability at the cooper surface because of ΔN < 3.6 (i.e. ΔN = − 0.206)61. Oleuropein was the electron donor in this experiment, while the copper surface was the acceptor.

Conclusions

Oleuropein was isolated from olive leaf and examined for its anticorrosion capability for copper in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution utilizing gravimetric, electrochemical, SEM, and EDX studies. To confirm the experimental findings, quantum chemical simulations on the produced Oleuropein were also accomplished.

The investigation yielded the following conclusions:

-

Many of the experimental data from LC–MS, FT-IR, 1H, and 13C-NMR analysis verify the molecular structure of Oleuropein.

-

Oleuropein demonstrated significant corrosion protection for copper in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution.

-

The efficiency of Oleuropein inhibition enhances with concentration and tends to decrease with temperature.

-

Oleuropein's inhibitory power increases with concentration, reached its maximum (98.92%) at 100 mg L−1, and it also functions as a mixed type inhibitor.

-

Rct, in specifically, achieves a value of 12,000 Ω cm2 at a dosage of 100 mg L−1 as compared to that recorded in the absence of Oleuropein (198 Ω cm2).

-

Adding Oleuropein increases the Ea from 10.64 kJ mol−1 (blank solution) to 38.79 kJ mol−1 (100 mg L−1 Oleuropein). Furthermore, we found that the positive value of ΔH* and ΔS* varied somewhat from − 186.86 J mol−1 K−1 (blank solution) to − 119.66 J mol−1 K−1 (100 mg L−1 Oleuropein).

-

SEM/EDX clearly shows the creation of an outer covering when the tested Oleuropein makes contact with the copper surface in acidic environments.

-

Quantum chemical factors clearly demonstrate that Oleuropein has considerable corrosion inhibition strength, which is consistent with experimental data.

References

Faes, W. et al. Corrosion and corrosion prevention in heat exchangers. Corros. Rev. 37(2), 131–155 (2019).

Chenoweth, J. M. General design of heat exchangers for fouling conditions. In Fouling Science and Technology (eds Melo, L. F. et al.) 477–494 (Kluwer, Dordrecht, 1988).

Deyab, M. A. Corrosion inhibition of heat exchanger tubing material (titanium) in MSF desalination plants in acid cleaning solution using aromatic nitro compounds. Desalination 439, 73–79 (2018).

Jamialahmadi, M. & Müller-Steinhagen, H. Heat exchanger fouling and cleaning in the dihydrate process for the production of phosphoric acid. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 85, 245–255 (2007).

Meroufel, A. A. Corrosion control during acid cleaning of heat exchangers. In Corrosion and fouling control in desalination industry (eds Saji, V. S. et al.) (Springer, Cham, 2020).

Hanbury, W. T., Hodgkiess, T. & Al-Omari, K. Aspects of acid cleaning operations in MSF plants. Desalination 158, 1 (2003).

Saber, T. M. H., Tag El Din, M. K. & Shams El Din, A. M. Dibutyl thiourea as corrosion inhibitor for acid washing of multistage flash distillation plant. Br. Corros. J. 27(2), 139–143 (1992).

Sherif, E. M. & Park, S. M. Effect of 2-Amino-5-ethylthio-1,3,4-thiadiazole on copper corrosion as a corrosion inhibitor in aerated acidic pickling solutions. Electrochim. Acta 51, 6556–6562 (2006).

Sherif, E. M. & Park, S. M. Inhibition of copper corrosion in acidic pickling solutions by N-phenyl-1,4-phenylenediamine. Electrochim. Acta 51, 4665–4673 (2006).

Matos, J. B. et al. Effect of cysteine on the anodic dissolution of copper in sulfuric acid medium. J. Electroanal. Chem. 570, 91–94 (2004).

Deyab, M. A. Ionic liquid as an electrolyte additive for high performance lead-acid batteries. J. Power Sources 390, 176–180 (2018).

Bahgat Radwan, A., Sliem, M. H., Okonkwo, P. C., Shibl, M. F. & Abdullah, A. M. Corrosion inhibition of API X120 steel in a highly aggressive medium using stearamidopropyl dimethylamine. J. Mol. Liq. 236, 220–231 (2017).

Luo, W. et al. A new pyridazine derivative synthesized as an efficient corrosion inhibitor for copper in sulfuric acid medium: Experimental and theoretical calculation studies. J. Mol. Liq. 341, 117370 (2021).

R. Laggoun, M. Ferhat, B. Saidat, A. Benghia, A. Chaabani, Effect of p-toluenesulfonyl hydrazide on copper corrosion in hydrochloric acid solution. Corros. Sci. 165, Article 108363 (2020).

Oukhrib, R. et al. The inhibitory effect of Saffron extract (Crocus sativus, L.) on copper corrosion in seawater. Chem. Sci. Rev. Lett. 4(13), 241–251 (2015).

Jmiai, A. et al. Application of Zizyphus lotuse—Pulp of Jujube extract as green and promising corrosion inhibitor for copper in acidic medium. J. Mol. Liq. 268, 102–113 (2018).

ASTM G1-03(2017) e1, Standard Practice for Preparing, Cleaning, and Evaluating Corrosion Test Specimens, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2017. www.astm.org.

Fu, S., Arráez-Román, D., Menéndez, J. A., Segura-Carretero, A. & Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Characterization of isomers of Oleuropein aglycon in olive oils by rapid-resolution liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray time-of-flight and ion trap tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 23, 51–59 (2009).

Aouidi, F. et al. Rapid quantitative determination of oleuropein in olive leaves (Olea europaea) using mid-infrared spectroscopy combined with chemometric analyses. Ind. Crops Prod. 37(1), 292–297 (2012).

Konno, K., Yasui, H., Hirayama, C. & Shinbo, H. Glycine protects against strong protein denaturing activity of oleuropein a phenolic compound in privet leaves. J. Chem. Ecol. 24, 735 (1998).

Deyab, M. A. 1-Allyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide as an effective organic additive in aluminum-air battery. Electrochim. Acta 244, 178–183 (2017).

El-Taib Heakal, F., Deyab, M. A., Osman, M. M., Nessim, M. I. & Elkholy, A. E. Synthesis and assessment of new cationic Gemini surfactants as inhibitors for carbon steel corrosion in oilfield water. RSC Adv. 7, 47335–47352 (2017).

Subramanian, A. K., Arumugam, S., Mallaiya, K. & Subramaniam, R. Synergistic effect on corrosion inhibiton efficiency of ginger affinale extract in controlling corrosion of mild steel in acid medium. J. Korean Chem. Soc. 57, 672–676 (2013).

Zaky, M. T., Nessim, M. I. & Deyab, M. A. Synthesis of new ionic liquids based on dicationic imidazolium and their anti-corrosion performances. J. Mol. Liq. 290, 111230 (2019).

Qiang, Y., Zhang, S., Xu, S. & Yin, L. The effect of 5-nitroindazole as an inhibitor for the corrosion of copper in a 3.0% NaCl solution. RSC Adv. 5, 63866–63873 (2015).

Deyab, M. A. Effect of nonionic surfactant as an electrolyte additive on the performance of aluminum-air battery. J. Power Sources 412, 520–526 (2019).

Li, C.-C. et al. Adsorption and corrosion inhibition of phytic acid calcium on the copper surface in 3 wt% NaCl solution. Corros. Sci. 83, 147–154 (2014).

Qiang, Y., Zhang, S., Yan, S., Zou, X. & Chen, S. Three indazole derivatives as corrosion inhibitors of copper in a neutral chloride solution. Corros. Sci. 126, 295–304 (2017).

Deyab, M. A., Nada, A. A. & Hamdy, A. Comparative study on the corrosion and mechanical properties of nano-composite coatings incorporated with TiO2 nano-particles, TiO2 nano-tubes and ZnO nano-flowers. Progr. Organ. Coat. 105, 245–251 (2017).

Iroh, J. O. & Su, W. Corrosion performance of polypyrrole coating applied to low carbon steel by an electrochemical process. Electrochim. Acta 46, 15–24 (2000).

Tasić, ŽZ., Petrović Mihajlović, M. B., Radovanović, M. B. & Antonijević, M. M. Electrochemical investigations of copper corrosion inhibition by azithromycin in 0.9% NaCl. J. Mol. Liq. 265, 687–692 (2018).

Zhang, G., Chen, C., Lu, M., Chai, C. & Wu, Y. Evaluation of inhibition efficiency of an imidazoline derivative in CO2-containing aqueous solution. Mater. Chem. Phys. 105, 331 (2007).

Espinoza-Vazquez, A. J., Rodriguez-Gomez, F. J., Mata, R., Madariaga-Mazon, A. & Ángeles-Beltran, D. Perezone as corrosion inhibitor for AISI 1018 steel immersed in NaCl saturated with CO2. J. Solid State Electrochem. 21, 1687 (2017).

Deyab, M. A., Keera, S. T. & El Sabag, S. M. Chlorhexidine digluconate as corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel dissolution in emulsified diesel fuel. Corros. Sci. J. 53, 2592–2597 (2011).

Hussin, M. H., Rahim, A. A., Ibrahim, M. N. & Brosse, N. The capability of ultrafiltrated alkaline and organosolv oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) fronds lignin as green corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in 0.5 M HCl solution. Measurement 78, 90–103 (2016).

Bommersbach, P., Dumont, C. A. & Millet, J. P. Hydrodynamic effect on the behaviour of a corrosion inhibitor film: characterization by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Electrochim. Acta 51, 4011–4018 (2006).

Deyab, M. A. Efficiency of cationic surfactant as microbial corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel in oilfield saline water. J. Mol. Liq. 255, 550–555 (2018).

Mu, G. & Li, X. Inhibition of cold rolled steel corrosion by Tween-20 in sulfuric acid: Weight loss, electrochemical and AFM approaches. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 289, 184–192 (2005).

Deyab, M. A. The influence of different variables on the electrochemical behavior of mild steel in circulating cooling water containing aggressive anionic species. J. Solid State Electrochem. 13, 1737–1742 (2009).

Ferreira, E. S., Giacomelli, C., Giacomelli, F. C. & Spinelli, A. Evaluation of the inhibitor effect of l-ascorbic acid on the corrosion of mild steel. Mater. Chem. Phys. 83, 129–134 (2004).

Hmamou, D. B. et al. Studies on the inhibitive effect of potassium ferrocyanide on the corrosion of steel in phosphoric acid. Res. Chem. Intermed. 39, 3475–3485 (2013).

Lebrini, M., Robert, F., Blandinières, P. A. & Roos, C. Corrosion inhibition by Isertia coccinea plant extract in hydrochloric acid solution. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci 6, 2443–2460 (2011).

Mobin, M., Zehra, S. & Parveen, M. l-Cysteine as corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in 1M HCl and synergistic effect of anionic, cationic and non-ionic surfactants. J. Mol. Liq. 216, 598–607 (2016).

Ouakki, M., Galai, M., Cherkaoui, M., Rifi, E. & Hatim, Z. Inorganic compound (Apatite doped by Mg and Na) as a corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in phosphoric acidic medium. Anal. Bioanal. Electrochem. 10(7), 943–960 (2018).

Finšgar, M. & Milošev, I. Inhibition of copper corrosion by 1,2,3-benzotriazole: A review. Corros. Sci. 52(9), 2737–2749 (2010).

Tan, B. et al. Insight into the corrosion inhibition of copper in sulfuric acid via two environmentally friendly food spices: Combining experimental and theoretical methods. J. Mol. Liq. 286, 110891 (2019).

Lgaz, H. et al. On the understanding of the adsorption of Fenugreek gum on mild steel in an acidic medium: Insights from experimental and computational studies. Appl. Surf. Sci. 463, 647–658 (2019).

Mendonça, G. L. F. et al. Understanding the corrosion inhibition of carbon steel and copper in sulphuric acid medium by amino acids using electrochemical techniques allied to molecular modelling methods. Corros. Sci. 115, 41–55 (2017).

Quartarone, G., Battilana, M., Bonaldo, L. & Tortato, T. Investigation of the inhibition effect of indole-3-carboxylic acid on the copper corrosion in 0.5 M H2SO4. Corros. Sci. 50, 3467–3474 (2008).

Pan, L., Han, Q., Xie, X., Xie, X. & Xiao, P. Corrosion prevention of the generator stator hollow copper conductor and water quality adjustment of its internal cooling water. Energy Power Eng. 1(1), 17–20 (2009).

Abd El-Rehim, S. S., Hassan, H. H., Deyab, M. A. & Abd El Moneim, A. Experimental and theoretical investigations of adsorption and inhibitive properties of Tween 80 on corrosion of aluminum alloy (A5754) in alkaline media. Z. Phys. Chem. 230, 67–78 (2016).

Deyab, M. A. Hydrogen evolution inhibition by L-serine at the negative electrode of a lead–acid battery. RSC Adv. 5, 41365–41371 (2015).

Deyab, M. A. & Abd El-Rehim, S. S. On surfactant-polymer association and its effect on the corrosion behaviour of carbon steel in cyclohexane propionic acid. Corros. Sci. J. 65, 309–316 (2012).

Deyab, M. A. Egyptian licorice extract as a green corrosion inhibitor for copper in hydrochloric acid solution. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 22, 384–389 (2015).

Guo, W., Chen, S., Feng, Y. & Yang, C. Investigations of triphenyl phosphate and bis-(2-ethylhexyl) phosphate self-assembled films on iron surface using electrochemical methods, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, and molecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 3109–3115 (2007).

Saha, S. K., Dutta, A., Ghosh, P., Sukul, D. & Banerjee, P. Novel Schiff-base molecules as efficient corrosion inhibitors for mild steel surface in 1 M HCl medium: experimental and theoretical approach. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 17898–17911 (2016).

Solmaz, R., Kardas, G., Yazici, B. & Erbil, M. Adsorption and corrosion inhibitive properties of 2-amino-5-mercapto-1,3,4-thiadiazole on mild steel in hydrochloric acid media. Colloids Surf. A 312, 7–17 (2008).

Gece, G. The use of quantum chemical methods in corrosion inhibitor studies. Corros. Sci. 50, 2981–2992 (2008).

Chermette, H. Chemical reactivity indexes in density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 20, 129–154 (1999).

Pearson, R. G. Absolute electronegativity and hardness: application to inorganic chemistry. Inorg. Chem. 27, 734 (1988).

Lukovits, I., Kalman, E. & Zucchi, F. Corrosion inhibitors—Correlation between electronic structure and efficiency. Corrosion 57, 3 (2001).

Acknowledgements

Taif University Researchers Supporting Project number (TURSP—2020/19), Taif University, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A.D.: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Roles/Writing—original draft; Writing—review and editing. G.M.: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Roles/Writing—original draft; Writing—review and editing. E.B.: Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Resources; Software; Validation; Visualization; Roles/Writing—original draft; Writing—review and editing. M.R.L.: Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Resources; Software; Validation; Visualization; Roles/Writing—original draft; Writing—review and editing. Q.M.: Funding acquisition; Software; Writing—review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Deyab, M.A., Mohsen, Q., Bloise, E. et al. Experimental and theoretical evaluations on Oleuropein as a natural origin corrosion inhibitor for copper in acidic environment. Sci Rep 12, 7579 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11598-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11598-7

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.