Abstract

Recently, amorphous Hf-B-Si-C-N coatings found to demonstrate superior high-temperature oxidation resistance. The microstructure evolution of two coatings, Hf7B23Si22C6N40 and Hf6B21Si19C4N47, annealed to 1500 °C in air is investigated to understand their high oxidation resistance. The annealed coatings develop a two-layered structure comprising of the original as-deposited film followed by an oxidized layer. In both films, the oxidized layer possesses the same microstructure with HfO2 nanoparticles dispersed in an amorphous SiOx-based matrix. The bottom layer in the Hf6B21Si19C4N47 coating remains amorphous after annealing while Hf7B23Si22C6N40 recrystallized partially showing a nanocrystalline structure of HfB2 and HfN nanoparticles separated by h-Si3N4 and h-BN boundaries. The HfB2 and HfN nanostructures form a sandwich structure with a HfB2 strip being atomically coherent to HfN skins via (111)-Hf monolayers. In spite of the different bottom layer structure, the oxidized/bottom layer interface of both films was found to exhibit a similar microstructure with a fine distribution of HfO2 nanoparticles surrounded by SiO2 quartz boundaries. The high-temperature oxidation resistance of both films is attributed to the particular evolving microstructure consisting of HfO2 nanoparticles within a dense SiOx-based matrix and quartz SiO2 in front of the oxidized/bottom layer interface acting as a barrier for oxygen and thermal diffusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ultra-high temperature ceramics of transition metal based borides, carbides, nitrides and their composites exhibit a combination of desirable properties including a high melting point, high hardness, superior oxidation and corrosion resistance and high thermal stability1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Recent attention to ZrB2-SiC and HfB2-SiC composites is due to their exceptional combination of high hardness and high oxidation resistance (>1000 °C), important characteristics for surface protection in extreme environments15,16. The HfB2-based materials in particular exhibit higher oxidation resistance compared to ZrB2-based materials and thus, possess more promise as high temperature protection coatings. Some potential applications include turbine blades and vanes, sharp wing leading edges and nose tips in hypersonic vehicles, atmospheric re-entry and rocket propulsion systems9,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24.

Our previous work has been focused on Hf-B-Si-C films that were found to exhibit high hardness (up to 37 GPa), along with high electrical conductivity and high oxidation resistance in air up to 800 °C25,26. In view of the important role of nitrogen in the high thermal stability of Si-B-C-N films27,28,29,30,31, nitrogen was incorporated recently into the Hf-B-Si-C system to stabilize its structure12, limit the release of boron and extend the oxidation resistance beyond 1000 °C. The Hf-B-Si-C-N films were deposited using pulse reactive magnetron co-sputtering of a single B4C-Hf-Si target in argon-nitrogen gas mixtures with a negative-voltage pulse length of 85 µs12,13,32 or 50 µs, [32 this work] and a short-lived high positive voltage overshoot (higher than 200 V, as shown in32) after the negative voltage pulses with a repetition frequency of 10 kHz. The base pressure before the deposition was 3 × 10−3 Pa12,13 or 1 × 10−3 Pa, [32 this work]. In paper13, we presented a study of the high-temperature oxidation resistance mechanism of Hf7B23Si17C4N45 film with a contamination level <4 at.%, which was prepared at a 20% N2 fraction in the gas mixture and annealed in air up to 1100–1500 °C. After a reduction of the base pressure to 1 × 10−3 Pa, we investigated the effects of a varying 0–50% N2 fraction in the gas mixture on the evolution of the elemental composition, structure, mechanical, electrical and optical properties, and oxidation resistance of the films32. Moreover, the effects of shortened (50 µs compared to 85 µs) voltage pulses on the film properties were investigated for selected N2 fractions in the gas mixture. Here, it should be mentioned that the negative voltage pulses on the sputtered target need to be sufficiently short to avoid micro-arcing at the target and thus, to produce high-quality defect-free films with low surface roughness. In paper32, we demonstrated very high oxidation resistance in air up to 1500 °C for two sufficiently hard (20–22 GPa) Hf-B-Si-C-N films deposited at the voltage pulse length of 50 µs: the electrically conductive Hf7B23Si22C6N40 film prepared at the 15% N2 fraction in the gas mixture, and the optically transparent Hf6B21Si19C4N47 film prepared at the 25% N2 fraction in the gas mixture, both with a contamination level <3 at.%.

In this work, the Hf7B23Si22C6N40 and Hf6B21Si19C4N47 films were prepared on SiC substrates and annealed in air up to 1500 °C. Comprehensive high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) and selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) studies were conducted to determine the microstructures that develop during high temperature exposure in these films and to understand their superior high-temperature oxidation resistance and the important effect of nitrogen incorporation (not investigated in13).

This study is a part of an overall program of our laboratories at UTA and UWB conducted to develop new, sufficiently hard, thin-film materials in the Hf-B-Si-C-N system with a controlled electrical conductivity and optical transparency, and with ultrahigh thermal stability in air. When the excellent oxidation resistance at elevated temperatures of thin-film materials is combined with a high optical transparency (e.g., as in the case of Si–B–C–N films30,31), they can be used for high-temperature protective coatings of electronic and optical elements. Alternatively, a combination of the high oxidation resistance and electrical conductivity is desirable for harsh-environment sensors, such as capacitive pressure, vibration and tip clearance sensors (e.g., for advanced gas turbine engines33,34,35,36).

The pulse magnetron sputter technique used makes it possible to deposit densified films onto substrates at a floating potential (i.e., without any substrate bias) due to increased kinetic energies of sputtered target material and process gas ions at the substrates, caused by the high positive voltage overshoots after the negative voltage pulses32. This is of key importance for industrial applications, particularly for production of thin-film materials on large area non-conductive substrates (no rf-induced bias needed).

Experimental

Material preparation

The Hf7B23Si22C6N40 and Hf6B21Si19C4N47 films were synthesized in a Balzers BAS 450PM sputtering system. The films were deposited on polished and ultrasonically cleaned SiC single crystal substrates using reactive magnetron sputtering from a single B4C-Hf-Si target in an argon-nitrogen gas mixture. The target (127 mm × 254 mm) was prepared by positioning p-type Si and Hf stripes on a B4C plate (6 mm thick) with fixed 65% B4C + 15% Hf + 20% Si fractions in the target erosion area. A pulsed dc power supply (Rübig MP120) was used to drive the magnetron operating at a 10 kHz repetition frequency with a 500 W average target power and a fixed 50 µs negative-voltage pulse length with a short-lived high positive voltage overshoot (higher than 200 V, as shown in32) after the negative voltage pulses. During sputtering, the voltage pulse duration of 50 µs is sufficiently short to avoid micro-arcing at the non-conductive layer formed on the B4C-Hf-Si target (for details see32). The base pressure prior to deposition was 1 × 10−3 Pa. The total pressure of the gas mixture during the deposition was 0.5 Pa with a N2 fraction being 15% and 25% for Hf7B23Si22C6N40 and Hf6B21Si19C4N47 film, respectively. The distance from target to substrate was 100 mm and the substrate temperature was maintained at 450 °C. The substrates were held at a floating potential. These conditions produced a film thickness of 1450 nm and 1240 nm for the Hf7B23Si22C6N40 and Hf6B21Si19C4N47, respectively. Rutherford backscattering spectrometry (RBS) and elastic recoil detection (ERD) with a Van de Graaf generator with a linear electrostatic accelerator were used to determine the film composition.

The annealing (annealing denotes a high temperature exposure and oxidation in air) experiments were conducted from room temperature up to 1500 °C using a symmetrical high resolution Setaram TAG 2400 system in synthetic atmospheric air (flow rate of 1 l/h). The heating and cooling rate was 10 °C/min and 30 °C/min, respectively.

Microstructure characterization

The crystallographic structure of the annealed films was first studied by X-ray diffraction (XRD) θ-2θ measurements utilizing a Bruker D8 Advance Diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation at 40 kV voltage and 40 mA current. The film microstructures were then studied by cross-section and plan-view TEM. Thin foil specimens were prepared by the procedure of mechanical grinding, polishing, and dimpling, followed by Ar-ion milling. A Hitachi H-9500 electron microscope was utilized operated at 300 keV with a point resolution of 0.18 nm.

Results and Discussion

XRD analysis

The as-deposited and annealed films were first examined by θ-2θ XRD analysis. Both as-deposited Hf-B-Si-C-N films have a pure amorphous structure as identified by XRD and further confirmed by TEM studies (see later section). Figure 1 shows θ-2θ XRD spectra of the annealed Hf6B21Si19C4N47 and Hf7B23Si22C6N40 films. The XRD spectrum of the former annealed film shows peaks at 2θ angles of 17.55°, 28.34°, 31.60°, 34.61° and 35.64° that can be identified as monoclinic HfO2 (m-HfO2, PDF #01-075-6426, a = 5.1187 Å, b = 5.1693 Å, c = 5.297 Å, β = 99.18°, P21/c)37 (100), (\(\bar{1}\)11), (111), (020) and (200), respectively. It should be noted that the latter peak is also close to orthorhombic HfO2 (002) (o-HfO2, PDF #01-070-2832, a = 5.0073 Å, b = 5.2276 Å, c = 5.058 Å, Pbcm), and tetragonal HfO2 (200) (t-HfO2, PDF #00-008-0342, a = 5.14 Å, c = 5.25 Å, P42/nmc). The peak located at the 2θ angle of 30.24° can correspond to (111) of the o-HfO2 and/or t-HfO2. This result is in agreement with our previous studies12,13 and indicates mainly formation of m-HfO2, o-HfO2 (and possibly t-HfO2) in the annealed Hf6B21Si19C4N47.

The XRD spectrum of the annealed Hf7B23Si22C6N40 film shows additional peaks besides those present in the spectrum of the annealed Hf6B21Si19C4N47 film. The peak at an angle of 39.48°, and broad peaks at angles of 56.70° and 68.00° match very well with the (200), (220) and (311) of face centered cubic (fcc) HfC0.5N0.5 (PDF#04-002-2469, a = 4.586 Å, Fm-3m), respectively. Note that the (111) HfC0.5N0.5 peak at 33.8° is on the left shoulder of the mHfO2 (020) peak. Also, the peaks at 25.80°, 42.03° and 58.79° match well with the (001), (101) and (110) of HfB2 (PDF#38-1398, hexagonal, a = 3.14 Å, c = 3.47 Å, P6/mmm)37. It is noted that the peak at 25.80° can also match a turbostratic structure of BN or B(C)N38 as reported previously27. Thus, in addition to HfO2, the annealed Hf7B23Si22C6N40 film showed formation of Hf(C)N solid solution, HfB2 and possibly BN. The XRD data and corresponding phases are summarized in Table 1.

TEM studies

Overall film structure

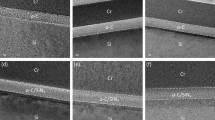

We have employed cross-section TEM for a detailed microstructure study of the annealed films. Figure 2(a,b) presents cross-section TEM images of the annealed Hf6B21Si19C4N47 and Hf7B23Si22C6N40 films, respectively. Both annealed films have a two-layered structure: a nanocomposite layer with discrete HfO2 nanoparticles embedded in an amorphous SiOx-based matrix on the top surface followed by the remaining of the original as-deposited film at the bottom. A similar film morphology with some distinct differences however (see later section), has also been observed in the annealed Hf7B23Si17C4N45 film studied previously12,13. The top composite layer in the present annealed films has nearly the same thickness of ~360 nm and exhibits nearly the same microstructure. The entire film thickness (the total of both layers) is ~1300 nm and ~1600 nm for the Hf6B21Si19C4N47 and Hf7B23Si22C6N40 film, respectively. Figure 2(c) is a SAED pattern of the top layer in the annealed Hf6B21Si19C4N47 film in a plan-view TEM foil. The diffraction rings 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 have a lattice spacing of 5.07 Å, 3.64 Å, 3.17 Å, 2.95 Å, 2.83 Å, 2.63 Å and 2.54 Å, respectively. The diffractions 1, 3 and 5 were uniquely identified to be the (100), (\(\bar{1}\)11) and (111) of m-HfO2, respectively. The diffraction 4 can be identified as the (111) of o-HfO2 or t-HfO2. While the diffraction rings 2, 6 and 7 can correspond to superposition of the (011)/(110) of m-HfO2 or (110) of o-HfO2, the (002) of m-HfO2 or (020) of o-HfO2 or (002) of t-HfO2, and the (020)/(200) of m-HfO2 or (002) of o-HfO2 or (200) of t-HfO2, respectively. Figure 2(c) confirms the presence of both m-HfO2 and o-HfO2 (with possible presence of t-HfO2) in the top layer.

The bottom layer in the annealed Hf6B21Si19C4N47 film exhibits a rather homogeneous amorphous structure as was further confirmed by electron diffraction, Fig. 2(d). However, the bottom layer in the annealed Hf7B23Si22C6N40 film exhibits a grainy structure. Figure 2(e) is a SAED pattern taken from this section of the film showing the presence of a nanocrystalline structure. The diffraction rings 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 have a lattice spacing of 4.30 Å, 3.35 Å, 2.92 Å, 2.64 Å, 2.53 Å, 2.29 Å, 2.20 Å and 1.62 Å, respectively. The diffraction rings 1, 2, 3 and 5 match very well with the h-Si3N4 (PDF #09-0250, a = 7.758 Å, c = 5.623 Å, P31c) (101), (200), (201) and (210), respectively. The diffraction rings 4, 6 and 8 can be identified as the (111), (200) and (220) of cubic Hf(C)N and the diffraction 7 can possibly correspond to the (101) of HfB2 (see comment regarding this diffraction in later section). These results clearly show that annealing caused crystallization in the original Hf7B23Si22C6N40 film while the amorphous structure in the annealed Hf6B21Si19C4N47 film was persistent.

As noted earlier, the top oxidized layer in both annealed films exhibited a similar microstructure. Figure 3(a) is a plan-view TEM image of the top nanocomposite oxidized layer of the annealed Hf7B23Si22C6N40 film showing a large number of HfO2 nanoparticles dispersed in a dense SiOx-based matrix. The HfO2 nanoparticles are mostly spherical with their size varying from ~15 nm to ~80 nm. It can also be seen that in some cases, nanoparticles merge together producing an ellipsoidal shape. HRTEM studies demonstrated the clear matrix has an amorphous structure. The presence of the m-HfO2 and o-HfO2 nanoparticles in this layer was further verified by HRTEM imaging. For example, the nanoparticle P1 in Fig. 3(b) presents two sets of lattice fringes with a spacing of 2.82 Å and 2.63 Å corresponding to (111) and (002) of m-HfO2, respectively. Similarly, the nanoparticle P2, Fig. 3(b), presents a set of lattice fringes with a spacing of 2.96 Å corresponding to (111) of o- or t-HfO2.

Upon annealing of these films, HfO2 nanoparticles are first nucleated at the oxidized/bottom layer interface followed by particle coarsening as the top surface is approached, Fig. 2. Subsequently, Si and more than likely B are oxidized forming a protective borosilicate matrix13. It has been shown that above 1100 °C, B2O3 reacts with SiO2 forming protective borosilicate glass that fills the pores in the amorphous SiO2 structure39 resulting in a dense amorphous SiOx-based matrix as shown in Fig. 3(a).

Microstructure of the bottom layer

Figure 4(a) is a typical HRTEM image of the bottom layer of the annealed Hf6B21Si19C4N47 film showing a pure amorphous structure. The regions with darker contrast more than likely correspond to Hf-rich areas and the brighter regions to light element (B, Si, C, N) rich regions. Figure 4(b) is a bright-field TEM image of the bottom layer of the annealed Hf7B23Si22C6N40 film presenting a quite different microstructure to that shown in Fig. 4(a). Faceted nanoparticles with clear and sharp edges were formed in this bottom film layer. The size of these faceted nanoparticles varies from a few nm up to 20 nm. The nanoparticles are expected to be Hf-rich structures (i.e., HfN, HfB2) whereas the boundary regions are rich in light elements. The boundary regions have a very complex structure and HRTEM was intensively used for a comprehensive study of its microstructure as described in the following section.

Figure 5(a) is a HRTEM image taken from the bottom layer of the annealed Hf7B23Si22C6N40 film presenting a mixture of different phases and structures in this region. The area designated by S1 shows lattice fringes with a spacing of 6.75 Å, that is close to the (100) of h-Si3N4. The presence of h-Si3N4 in the bottom layer of the annealed Hf7B23Si22C6N40 film was confirmed by HRTEM images from other regions that show lattice fringes with the electron beam parallel to the zone axis of the h-Si3N4. One example is shown in Fig. 5(b) presenting a HRTEM image with the electron beam parallel to [\(\bar{1}\bar{1}1\)] axis of h-Si3N4 along with the corresponding fast Fourier transformation (FFT). The h-Si3N4 was found in the light boundary regions shown in Fig. 4(b).

Besides the presence of h-Si3N4, curved lattice fringes with similar characteristics to an onion structure were frequently observed in the boundary areas, as shown in the S2 region in Fig. 5(a). The spacing between the curved lattice fringes is about 3.4 to 3.5 Å, which is very close to the lattice spacing of the (002) of hexagonal BN, which is about 3.33 Å. The nucleation and formation of h-BN has been found in our previous studies of Si-B-C-N film annealed up to 1700 °C in air28. The spacing of the curved BN lattice fringes in the latter film was about 3.42 Å, 3% larger than the (002) lattice fringes in the bulk BN, which matches well with the result in the current study. In fact, the somewhat larger lattice spacing can be due to incorporation of C into BN forming a turbostratic B(C)N structure as reported earlier27,38. Figure 5(c) presents a HRTEM image and the corresponding FFT from another boundary region showing the curved lattice fringes of BN, in which in addition to the primary lattice fringes of (002)-BN, another set of fringes with a spacing of 2.19 Å corresponding to (100) of BN were observed. This provides solid evidence for the formation of BN in the boundary region in the bottom layer of the annealed Hf7B23Si22C6N40 film.

The thin, long strip designated by S3 in Fig. 5(a), corresponding to a dark area in Fig. 4(b), was identified to be HfB2 viewed along its [010] direction. The horizontal lattice fringes have a spacing of 3.45 Å corresponding to (001) HfB2 while the vertical fringes have a spacing of 2.71 Å corresponding to (100) HfB2. The crystal S4 underneath the S3 HfB2 strip was identified to be fcc HfN viewed along its [110] direction. One set of the {111} planes are parallel to the (001) of HfB2. The two regions on the top of the HfB2 strip designated as S5 and S6 are also HfN domains. The lattice fringes in the two regions have a spacing of 2.67 Å, corresponding to (111) of HfN.

Figure 5(a) shows that the HfN nanoparticles S4, S5, and S6 are atomically coherent to the HfB2 strip S3. After intensive examinations of several other areas, we found that the HfB2 crystals were formed in a strip shape and always co-existed with HfN nanoparticles via atomically coherent interfaces. It was interesting to note that even though the HfN nanoparticles can nucleate independently, the HfB2 nanostructures were always formed coherently on interfaces with HfN. This tends to indicate that HfB2 forms first out of the amorphous structure and its (001) acts as a low energy nucleation site for the HfN phase. Such a sequence of formation is consistent with the lower enthalpy of formation of HfB2 compared to HfN40.

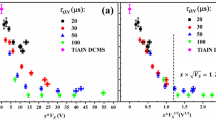

Figure 6(a) is a representative HRTEM image showing a sandwich structure with a central thin strip of HfB2 and two thicker skins of HfN. The central HfB2 strip has a thickness of 6 unit dimensions of c-axis (~2 nm) along the vertical direction, i.e., the [001] direction. The long axis of the HfB2 strip is along the [100] (horizontal direction) and the [010] is along the normal to the paper. The interfaces between the HfB2 core and two HfN skins are the (001) of HfB2. They are flat and atomically sharp. The two HfN skins are coherent and atomically joined to the HfB2 strip at the (001) of HfB2 via a specific orientation relationship:

(a) HRTEM image of a HfB2 and HfN sandwich structure; (b,c) atomic structure of HfB2 and HfN unit cell, respectively; (d) projection of coherently joined HfB2 and HfN structures along the HfB2-[010]; (e) a simulated HRTEM image calculated using a defocus of 17 nm and a thickness of 2.3 nm; (f) HRTEM image of the HfB2/HfN interface.

This coherent joining of the two different structures is not quite surprising and can be understood. HfB2 is a close packed hexagonal structure and can be obtained by sequentially packing the close-packed (001) monolayers of Hf (label as “AHf”) and B (label as “BB”) along the [001] direction, AHfBBAHfBBAHfBB…, Fig. 6(b). Due to its small size, B atoms can fill the two types of interstices on the top of the Hf monolayer, resulting in the atomic B:Hf ratio of 2:1. HfN is a fcc structure and can be obtained by sequentially packing the closed-packed (111) monolayer of Hf (labelled as AHf, BHf, CHf) and N (labelled as AN, BN and CN) in the way of AHfBNCHfANBHfCNAHfBNCHfANBHfCN…, Fig. 6(c). The Hf monolayers in both HfB2 and HfN have the same arrangement. The shortest Hf-Hf bonds (also the major bonds) are 3.21 Å in HfN and 3.14 Å in HfB2 (with a small mismatch of ~2%), indicating that the Hf monolayers in HfN and HfB2 can be interchangeable. Therefore, it is quite conceivable that HfB2 and HfN can coherently join to each other by sharing the Hf monolayer, for example,---AHfBBAHfBBAHfBNCHfANBHfCN---. Figure 6(d) shows a projection of such coherently joined HfB2 and HfN structure viewed along the direction of HfB2-[010]. Figure 6(e) is a simulated HRTEM image of such a structural model calculated using a defocus of 17 nm and a thickness of 2.3 nm. The simulated image matches well with the experimental HRTEM image shown in Fig. 6(f). Actually, the small size of the HfB2 strip (~2 nm) and the misfit coherency strain at the HfN/HfB2 interface can provide an explanation for the somewhat larger lattice spacing of the (101) HfB2 (2.2 Å vs 2.14 Å) observed in the SAED pattern for this phase, Fig. 2(e).

Thus, the present results reveal an interesting crystallization in the bottom layer of the annealed Hf7B23Si22C6N40 film with formation of HfB2 and HfN nanoparticles surrounded by Si3N4 and BN boundaries. It is more interesting that this crystallization was not observed in the Hf6B21Si19C4N47 film with higher N content. The results clearly show that even a small difference in the N content can stabilize the amorphous structure at high temperatures.

Oxidized/bottom layer interface

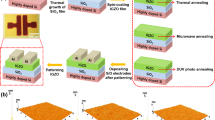

The interfaces between the bottom and oxidized layers in both annealed Hf-B-Si-C-N films were further studied using cross-section HRTEM. In the annealed Hf6B21Si19C4N47 film, densely packed ultra-fine size nanoparticles were nucleated at the interface between the bottom and oxidized layer, Fig. 7(a). These small nanoparticles gradually coarsened into spherical particles (~20 to 30 nm) towards the top surface. Figure 7(c) is a HRTEM image of the interface showing the presence of both m-HfO2 (particles T1 and T3 with (111) lattice fringes and spacing of 2.84 Å) and o-HfO2 (particles T2 and T4 with (101) lattice fringes and spacing of 2.96 Å). The small particles have a size of ~6 nm with an irregular shape (T1, T2 and T3) indicating an early nucleation stage. The larger particle T4 that has a size of ~14 nm possesses a spherical shape to minimize surface energy. It was interesting to note that the boundaries between HfO2 nanoparticles and matrix were no longer purely amorphous. High temperature, β-quartz SiO2 (PDF #11-0252, a = 5.002 Å, c = 5.454 Å, P3221) formation was observed at the boundary area of the HfO2 particles in the interface region, as evidenced by the presence of (101) lattice fringes with a spacing of ~3.4 Å. Thus, the present evidence suggests that as oxygen diffuses and reaches the interface, it reacts with Hf atoms in the amorphous structure and nucleates HfO2 nanoparticles. As the amorphous structure is depleted from Hf, Si atoms react with oxygen at the depleted HfO2/matrix boundaries forming quartz SiO2. In fact, this formation process at the boundaries of the spherical HfO2 particles seems consistent with the exhibited (101) SiO2 curved lattice fringes instead of straight lines observed in all HRTEM images. It should also be noted that due to their ultrafine scale and curved lattice planes, detection of such a structure by XRD or even SAED is very difficult. It is also important to note that formation of quartz was observed only in the oxidized/bottom layer interface region and not in the upper oxidized layer where more intense oxidation conditions prevail.

Figure 7(b) is a cross-section TEM image of the oxidized/bottom layer interface in the annealed Hf7B23Si22C6N40 film. As shown earlier, the bottom layer in this film has an entirely different microstructure. During annealing, the amorphous structure was partially crystalized and resulted in the formation of HfB2, HfN, Si3N4, and BN. Thus, as oxygen diffuses in this film and reaches the interface, oxidation of the individual crystalline phases takes place. Due to differences in the oxidation kinetics of the various crystalline phases in the bottom layer of this film, the oxidized/bottom layer interface is not sharp as the one in the Hf6B21Si19C4N47 film, Fig. 7(a). As shown in Fig. 7(b), a partially oxidized zone develops in the Hf7B23Si22C6N40 film. Just above the interface, spherical HfO2 particles form along with much enriched SiO2 crystalline structures, Fig. 7(d), similar to those observed in the Hf6B21Si19C4N47 film, Fig. 7(a). A closer observation of the image in Fig. 7(d) shows extensive formation of curved quartz lattice fringes that could not have been produced with the same process as that in the Hf6B21Si19C4N47 film. Quartz formation in this film is attributed to oxidation of pre-existing hexagonal Si3N4 boundaries around HfN and HfB2 nanodomains. Thus, a similar microstructure involving a fine distribution of HfO2 nanoparticles surrounded by quartz boundaries developed in the oxidized/bottom layer interface region of both films.

It is important to note that X-ray energy-dispersive spectroscopy analysis showed that both bottom layers in the annealed films are oxygen free. Thus, two entirely different oxidation processes occur in the two films; the first involves oxidation of individual elements out of the amorphous structure and the second, oxidation of nanocrystalline phases (HfB2, HfN, Si3N4, and BN) formed during annealing. In spite of the differences in the aforementioned oxidation process, it should be emphasized that both films exhibit similar microstructures at the oxidized/bottom layer interface and in the top oxidized layer. Furthermore, both films have been found to possess high oxidation resistance with no mass change after annealing up to 1300 °C32. It is interesting to note that even though annealing up to 1500 °C produces an oxidized layer of the same thickness (360 nm) in both films, it also results in some small differences in the oxidation behavior that can be attributed to their microstructures. Film Hf7B23Si22C6N40 exhibits a slow mass gain (less than 10 μg/cm2) while film Hf6B21Si19C4N47 shows negligible mass change32. This behavior confirms that both oxidation and volatilization occur simultaneously during annealing. The latter as-deposited film contains more nitrogen and as such, more nitrogen will be released during oxidation resulting in a lower or no mass gain. On the other hand, the former film crystallizes during annealing and therefore, oxygen can penetrate more easily into the film. In this case, oxygen can be present not only in the top 360 nm oxidized layer but also in the partially oxidized interface zone resulting in a mass gain.

Based on the present results, the high temperature oxidation resistance of both films can be attributed to the similar microstructures that develop in the oxidized layer and its interface with the bottom layer in spite of the differences in the oxidation process. In both films, oxidation results in a high density of HfO2 nanoparticles within a dense amorphous SiOx-based matrix and quartz SiO2 formation in front of the base layer. In view of the presence of low thermal conductivity HfO2 (0.49–0.95 Wm−1K−1) nanoparticles, dense SiOx-based matrix and high density SiO2 nanoquartz (2.5 g/cm3), an effective oxygen and thermal diffusion barrier is produced at the interface that can result in high temperature oxidation resistance. It is important to note that the oxidation behavior of the present films produced with the present new deposition process shows significant improvements from previously studied Hf7B23Si17C4N45 film13. Note that the latter film annealed up to 1500 °C exhibited a significantly thicker (544 nm) oxide layer composed of two sublayers. One next to the as-deposited film, composed of a dense population of HfO2 nanoparticles (produced by nucleation and growth) and a top, surface sublayer with coarsened and dispersed HfO2 nanoparticles (produced by Ostwald ripening). It is interesting that the top sublayer was absent in the oxide layer of the present films that exhibited a much smaller thickness (360–370 nm, more than 30% reduction). Another distinct difference is that a continuous array of HfO2 nanoparticles is present at the top surface of the present oxide layers, Fig. 2(a,b). This clearly indicates the high stability of the HfO2 nanoparticles in the present microstructures more than likely due to high quality, defect-free films produced by the present deposition process.

Finally, it should be noted that the crystallization observed in the Hf7B23Si22C6N40 film can actually be utilized as a route to enhance the hardness of the as-deposited film. Hf7B23Si22C6N40 films annealed in He up to 1300 °C (no oxidation) were found to exhibit a hardness of about 26 GPa due to the evolved nanocrystalline microstructure. Thus, this annealing procedure in an inert environment can be utilized to produce films with high hardness along with excellent high temperature oxidation resistance.

Summary

Both annealed Hf-B-Si-C-N films exhibit a two-layered structure comprising the original as-deposited film at the bottom and an oxidized layer at the top. In both films, the oxidized layer is composed of m-HfO2 and/or o-HfO2 embedded in an amorphous SiOx-based matrix. The bottom layer in the Hf6B21Si19C4N47 film remains amorphous while that in the Hf7B23Si22C6N40 film is partially crystallized exhibiting a nanocomposite structure of HfB2 and HfN nanoparticles surrounded by h-Si3N4 and h-BN boundary phases. The HfB2 and HfN nanoparticles found to form a sandwich structure with a HfB2 strip core being atomically coherent to HfN skins via a (111) Hf monolayer. The oxidized/bottom layer interface of the Hf6B21Si19C4N47 film is characterized by a high density of HfO2 nuclei surrounded by SiO2 quartz boundaries resulting from the oxidation of the amorphous structure. The interface of the Hf7B23Si22C6N40 film shows a similar HfO2/SiO2 quartz boundary microstructure that is a result of oxidation of the crystalline phases (HfN, HfB2 and h-Si3N4) produced during annealing. The high temperature oxidation resistance of these films is attributed to the particular microstructure involving formation of HfO2 nanoparticles in a SiOx-based matrix along with quartz formation at the oxidized/bottom layer interface that acts as a barrier for oxygen and thermal diffusion.

Data Availability

All experimental deposition conditions and characterization procedures, methods and data are provided in the text. Any clarifications will be available by contacting the corresponding author.

References

Mitterer, C. Borides in thin film technology. J. Solid State Chem. 133, 279–291 (1997).

Wiedemann, R. & Oettel, H. Tempering behaviour of TiB2 coatings. Surf. Eng. 14, 299–304 (1998).

Karlsdottir, S. N. & Halloran, J. W. Rapid oxidation characterization of ultra‐high temperature ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 90, 3233–3238 (2007).

Fahrenholtz, W. G., Hilmas, G. E., Talmy, I. J. & Zaykoski, J. A. Refractory diborides of zirconium and hafnium. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 90, 1347–1364 (2007).

Opeka, M. M., Talmy, I. G., Wuchina, E. J., Zaykoski, J. A. & Causey, S. J. Mechanical, thermal, and oxidation properties of refractory hafnium and zirconium compounds. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 19, 2405–2414 (1999).

Opeka, M. M., Talmy, I. G. & Zaykoski, J. A. Oxidation-based materials selection for 2000 °C+ hypersonic aerosurfaces: theoretical considerations and historical experience. J. Mater. Sci. 9, 5887–5904 (2004).

Opila, E., Levine, S. & Lorincz, J. Oxidation of ZrB2- and HfB2-based ultra-high temperature ceramics: Effect of Ta additions. J. Mater. Sci. 39, 5969–5977 (2004).

Monteverde, F. & Bellosi, A. The resistance to oxidation of an HfB2-SiC composite. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 25, 1025–1031 (2005).

Carney, C. M. Oxidation resistance of hafnium diboride-silicon carbide from 1400 to 2000 °C. J. Mater. Sci. 44, 5673–5681 (2009).

Carney, C. M., Mogilvesky, P. & Parthasarathy, T. A. Oxidation behavior of zirconium diboride silicon carbide produced by the spark plasma sintering method. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 92, 2046–2052 (2009).

Ren, X., Li, H., Chu, Y., Fu, Q. & Li, K. Ultra-high-temperature ceramic HfB2-SiC coating for oxidation protection of SiC-coated carbon/carbon composites. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 12, 560–567 (2015).

Zeman, P. et al. Superior high-temperature oxidation resistance of magnetron sputtered Hf–B–Si–C–N film. Ceram. Int. 42, 4853–4859 (2016).

Zhang, M. H. et al. Study of the high-temperature oxidation resistance mechanism of magnetron sputtered Hf7B23Si17C4N45 film. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 36, 021505 (2018).

Zhang, M. H. et al. A study of the microstructure evolution of hard Zr–B–C–N films by high-resolution transmission electron microscopy. Acta Mater. 77, 212–222 (2014).

Monteverde, F., Bellosi, A. & Scatteia, L. Processing and properties of ultra-high temperature ceramics for space applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 485, 415–421 (2008).

Ghosh, D. & Subhash, G. Recent progress in Zr (Hf)B2 based ultrahigh temperature ceramics in Handbook of Advanced Ceramics (2nd Edition), Materials, Applications, Processing, and Properties (ed. Somiya, S.) 267–269 (Academic Press 2013).

Zapata-Solvas, E., Jayaseelan, D. D., Lin, H. T., Brown, P. & Lee, W. E. Mechanical properties of ZrB2- and HfB2- based ultra-high temperature ceramics fabricated by spark plasma sintering. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 33, 1373–1386 (2013).

Wuchina, E. et al. Designing for ultra-high temperature applications: the mechanical and thermal properties of HfB2, HfCx, HfNx and αHf. J. Mater. Sci. 39, 5939–5949 (2004).

Chamberlain, A. L., Fahrenholtz, W. G. & Hilmas, G. E. High-strength zirconium diboride-based ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 87, 1170–1172 (2004).

Mallik, M., Ray, K. K. & Mitra, R. Oxidation behavior of hot pressed ZrB2-SiC and HfB2-SiC composites. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 31, 199–215 (2011).

Han, J., Hu, P., Zhang, X., Meng, S. & Han, W. Oxidation-resistant ZrB2-SiC composites at 2200 °C. Compos. Sci. Technol. 68, 799–806 (2008).

Monteverde, F. & Bellosi, A. Microstructure and properties of an HfB2-SiC composite for ultra-high temperature applications. Adv. Eng. Mater. 6, 331–336 (2004).

Corral, E. L. & Loehman, R. E. Ultra-high temperature ceramic coatings for oxidation protection of carbon-carbon composites. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 91, 1495–1502 (2008).

Carney, C. M., Parthasarathy, T. A. & Cinibulk, M. K. Oxidation resistance of hafnium diboride ceramics with additions of silicon carbide and tungsten boride or tungsten carbide. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 94, 2600–2607 (2011).

Zhang, M. H. et al. Effect of the Si content on the microstructure of hard, multifunctional Hf-B-Si-C films prepared by pulsed magnetron sputtering. Appl. Surf. Sci. 357, 1343–1354 (2015).

Kohout, J. et al. Hard multifunctional Hf–B–Si–C films prepared by pulsed magnetron sputtering. Surf. Coat. Technol. 257, 301–307 (2014).

Zeman, P., Čapek, J., Čerstvý, R. & Vlček, J. Thermal stability of magnetron sputtered Si-B-C-N materials at temperatures up to 1700 °C. Thin Solid Films 519, 306–311 (2010).

He, J. et al. Microstructure characterization of high-temperature, oxidation resistant Si-B-C-N films. Thin Solid Films 542, 167–173 (2013).

Čapek, J. et al. Effect of the gas mixture composition on high-temperature behavior of magnetron sputtered Si-B-C-N coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 203, 466–469 (2008).

Kalaš, J. et al. High-temperature stability of the mechanical and optical properties of Si-B-C-N films prepared by magnetron sputtering. Thin Solid Films 518, 174–179 (2009).

Vlček, J. et al. Pulsed reactive magnetron sputtering of high-temperature Si–B–C–N films with high optical transparency. Surf. Coat. Technol. 226, 34–39 (2013).

Šímová, V. et al. Magnetron sputtered Hf–B–Si–C–N films with controlled electrical conductivity and optical transparency, and with ultrahigh oxidation resistance. Thin Solid Films 653, 333–340 (2018).

Young, D. J., Du, J., Zorman, C. A. & Ko, W. H. High-temperature single-crystal 3C-SiC capacitive pressure sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 4, 464–470 (2004).

Fabian, T., Prinz, F. B. & Brasseur, G. Capacitive sensor for active tip clearance control in a palm-sized gas turbine generator. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 54, 1133–1143 (2005).

Chen, L. & Mehregany, M. A silicon carbide capacitive pressure sensor for in-cylinder pressure measurement. Sens. Actuators A 145–146, 2–8 (2008).

Hezarjaribi, Y., Hamidon, M. N., Sidek, R. M. & Keshmiri, S. H. Analytical and simulation evaluation for diaphragm’s deflection and its applications to touch mode MEMS capacitive pressure sensors. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 3, 4281–4292 (2009).

International Centre for Diffraction Data, PDF-2 Database Sets 1–47, Pennsylvania, USA (1997).

Alkoy, S., Toy, C., Gonul, T. & Tekin, A. Crystallization behavior and characterization of turbostratic boron nitride. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 17, 1415–1422 (1997).

Vlček, J. et al. Magnetron sputtered Si-B-C-N films with high oxidation resistance and thermal stability in air at temperatures above 1500 °C. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 26, 1101–1108 (2008).

Colinet, C. & Tedenac, J.-C. Enthalpies of formation of transition metal diborides: a first principles study. Crystals 5, 562–582 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation Award No. NSF/CMMI DMREF-1335502 and by the Czech Science Foundation Project No. 17-08944S.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.Z., V.S. and J.V. synthesized the coatings and Y.S., J.C.J. and E.I.M. conducted the TEM study and analysis. J.C.J. and E.I.M. wrote the manuscript and all authors reviewed it and provided comments.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, Y., Jiang, J.C., Zeman, P. et al. Microstructure evolution in amorphous Hf-B-Si-C-N high temperature resistant coatings after annealing to 1500 °C in air. Sci Rep 9, 3603 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40428-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40428-6

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.