Abstract

We report on the tunable edge-plasmon-enhanced absorption of phosphorene nanoribbons supported on a dielectric substrate. Monolayer anisotropic black phosphorous (phosphorene) nanoribbons are explored for light trapping and absorption enhancement on different dielectric substrates. We show that these phosphorene ribbons support infrared surface plasmons with high spatial confinement. The peak position and bandwidth of the calculated phosphorene absorption spectra are tunable with low loss over a wide wavelength range via the surrounding dielectric environment of the periodic nanoribbons. Simulation results show strong edge plasmon modes and enhanced absorption as well as a red-shift of the peak resonance wavelength. The periodic Fabry-Perot grating model was used to analytically evaluate the absorption resonance arising from the edge of the ribbons for comparison with the simulation. The results show promise for the promotion of phosphorene plasmons for both fundamental studies and potential applications in the infrared spectral range.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Studies of the light-matter interaction have been conducted for many materials, commonly focusing on noble metal films and nanostructures. Noble metals (gold, silver, etc.) support strong surface plasmon confinement. Surface plasmons are collective wave modes of conduction band electron oscillations at the interface between two materials; the waves are coherent with an incident oscillating electromagnetic field1,2,3,4. Strong locally confined fields can lead to enhanced light absorption and Raman scattering. The response of plasmonic metals is predominantly limited to the spectral range from ultraviolet to near-infrared (NIR). Beyond this spectral range, plasmons generate weak field confinement, have narrow spectral resonance due to large negative permittivity5, and exhibit very limited tunability due to high losses4,5,6.

As an alternative, two-dimensional (2D) materials such as graphene have demonstrated low attenuation of surface plasmon resonance, which is attributed to a unique band structure and high carrier mobility7,8. Graphene plasmons typically occur for the spectral range spanning mid-IR to low terahertz8,9. This has been achieved experimentally through a wide range of tuning mechanisms – higher doping levels, reduced structure dimensions, and gate modulation9,10,11,12. Fabricating graphene requires a substrate and a dielectric environment, which causes the plasmon-phonon modes to split into two hybrid modes. The dielectric environment surrounding graphene plasmonic structures can also cause weak dispersion and short lifetimes. The coupling between phonons and the plasmon damping effect hinder the utilization of graphene for enhanced light absorption in the low terahertz to mid-IR range12,13,14.

Very recently, black phosphorus (BP), a layered semiconductor with a two-dimensional “puckered” hexagonal structure in each monolayer (known as phosphorene), has gained attention in the scientific community as a potential candidate to study surface plasmon polaritons15,16,17,18,19,20. Theoretical and simulation results have revealed that properties of black phosphorous surface plasmons include polarization dependence when exposed to an electromagnetic field21,22, dependence on the size of the monolayer23, a quantized magnetic field indicated by discretized anisotropic magneto-excitons24, and damping point defects and potential for long-range disorder25. These features are attributed to its high mobility and highly tunable, layer-dependent, direct bandgap (0.3 eV in bulk to 2 eV in a monolayer)26,27,28, as well as its highly anisotropic in-plane electronic and optical properties28. In addition, these desirable properties make BP suitable for other optical material applications such as hyperspectral imaging, thermal imaging, photodetectors in silicon photonics, and terahertz transistors29,30,31,32. To date, these opto-electronic properties have been limited to fewer applications due to the instability of BP in ambient conditions33,34,35,36,37.

In this paper, we explore BP as an alternative 2D material to address the challenges faced by metals and graphene for surface plasmon resonance responses to incident light in the mid- to far-infrared spectral range. First, we focus on a theoretical analysis of the dispersion relation and the confinement strength of surface plasmon modes excited by a linearly-polarized plane wave on an infinite phosphorene sheet, taking the surrounding dielectric media into account. Next, we expand the theoretical work to periodic monolayer BP nanoribbons using finite element simulations. We select a design that can be easily realized in experiments and use numerical simulations to describe the tunable resonance and enhanced absorption of the plasmonic modes for capping layers and substrates of different dielectric values. Further, a theoretical periodic grating model is implemented to determine the wavelength of the resonant absorption peak by calculating the phase of the reflected wave at the edge of the nanoribbon. We also extend the numerical simulation to study BP nanoribbons enhancing absorption in different directions based on the optical conductivity change and ribbon width. Finally, we study mechanisms of preserving phosphorene from oxidation effects while maintaining edge plasmon enhanced absorption. Although phonon-related damping pathways for BP plasmons remain unknown, this work highlights several attractive features of tunable mid- to far-infrared BP plasmons.

Results

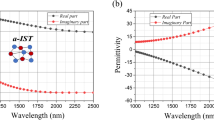

Black Phosphorene Conductivity Model

Anisotropic, angular frequency (ω) dependent, dynamical, 2D surface local conductivity of BP can be described by the semi-classical Drude model expression21.

Here, j denotes the position along the arm-chair direction (x) and zigzag direction (y). D j = πNe2/m j is the Drude weight, which is dependent on the electron charge, e, anisotropic effective electron mass, m j , and electron density, N. η = 1/τ is the scattering rate (τ is the carrier relaxation time, related to finite damping.) The anisotropic effective mass for monolayer or bulk BP gives rise to anisotropic conductivity. Along a plane near the Γ-point in the BP band diagram, the effective electron mass along the x- and y-directions are \({m}_{cx}={\hslash }^{2}/(\frac{2{\gamma }^{2}}{{\rm{\Delta }}}+{\eta }_{c})\) and \({m}_{cy}={\hslash }^{2}/2\,{v}_{c}\)21,38. Values of the conduction band parameters for monolayers include the following: \({\eta }_{c}={\hslash }^{2}/0.4\,{m}_{0}\), \({v}_{c}={\hslash }^{2}/1.4\,{m}_{0}\), \({\rm{\Delta }}\,=2\,{\rm{eV}}\), and γ = 4a/π eVm, where a = 0.223 nm and π/a is the width of the Brillouin Zone in the x-direction21,38. These are chosen such that they yield the known conduction band effective masses m cx ≈ 0.15 m0 and m cy ≈ 0.7 m0 of monolayer BP. It is worth mentioning that the band parameters are highly sensitive to the number of BP layers; any small change explicitly affects anisotropic effective masses38. We choose the electron carrier density to be from N = 1012 to 5 × 1013 cm−2, and a scattering rate of η = 10 meV that accounts for the finite damping21. These N values are within the range reported in ab initio studies, giving this scattering rate39,40. Monolayer phosphorene is an ultra-thin film with a thickness of t BP ≈ 0.7 nm27. Although the monolayer thickness extracted from bulk black phosphorus is 0.5 nm39, we choose a slightly larger value consistent with the measured height of most samples18 because this is the one most likely to be realized in experiments and the one that will determine observed plasmonic effects. We can introduce a phosphorene layer with volumetric anisotropic permittivity41 converting the 2D surface conductivity into a 3D conductivity using the relation σ2D = t BP σ3D42. Hence, the 3D complex anisotropic dielectric function for monolayer BP from Eq. (1) is

where ε r = 5.65 is the relative permittivity for monolayer BP43. This approach has been previously used in the investigation of surface plasmons in BP23 and graphene 2D films and nanoribbons44.

The theoretical dispersion calculation of the plasmonic wave for the transverse magnetic (TM) and transverse electric (TE) modes in a continuous BP monolayer was performed following the method outlined by Ju et al. and Grigorenko et al.45,46. A BP layer is situated in the x-y plane, sandwiched between semi-infinite dielectric materials of relative permittivity ε1 (above) and ε2 (below). Accordingly, calculations for TM mode and TE mode, propagating perpendicular to the interface between the dielectric medium, are

where ε0 is the vacuum permittivity, μ0 is the vacuum permeability, \({k}_{z1}=\,\sqrt{{k}_{jj,1}^{2}-{\varepsilon }_{1}{k}_{0}^{2}}\) and \({k}_{z2}=\,\sqrt{{k}_{jj,2}^{2}-{\varepsilon }_{2}{k}_{0}^{2}}\) are wave vectors above and below the BP layer and k0 is the vacuum wave vector. A rough measure of the plasmon mode confinement comes from the real part of Eq. (3a) and (3b). This can be attained when \({k}_{jj,1}^{2}\gg {\varepsilon }_{1}{k}_{0}^{2}\) and \({k}_{jj,2}^{2}\gg {\varepsilon }_{2}{k}_{0}^{2}\), leading to kz1 = i(ε1 + ε2)ε0ω/σ jj for the TM mode and kz1 = iσ jj μ0ω/2 for the TE mode. Accordingly, the surface plasmon confinement factor, n eff , for the infinite BP sheet is related to the free-space wave vector by n eff = kz1/k0. The real part of n eff is directly related to the degree of confinement, and the imaginary component corresponds to the propagation length. Figure 1(a) plots analytical results of TM mode light dispersion for four selected dielectric substrates with n1 taken to be air. The confinement strength indicates a directly proportional effect of the dielectric constant of the materials surrounding the infinite BP layer. The plasmon confinement strength is on the order of a hundred over the IR range, being comparable to that of graphene47, while the value for noble metals is close to one. It can be noted that TE mode confinement is barely possible, as the imaginary part of the conductivity, σ jj , in Eq. (3b) is positive over the infrared range of the spectrum, corresponding to high loss. It is worth noting that the surface plasmon dispersion can be controlled by the optical conductivity of phosphorene via N. Doing so enables switching between surface plasmon modes that are strongly IR-supported and those that are not.

Simulation of the electromagnetic response of illuminated BP. (a) Plot of the real part of the SPP modes supported by a BP infinite sheet for four different dielectric media as measured by its vacuum wave vector. (b) 3D schematic of periodically patterned phosphorene nanoribbons on a dielectric layer (light blue) atop a gold reflective surface. Period, P, and ribbon length, w, are labeled. (c) Cross-sectional view of (b) with the BP, Au, two dielectric layers, n1 and n2, and light propagation and polarization directions, E and k, labeled. (d–f) Calculated distributions of the electric field enhancement, which is defined as the ratio of the local electric field amplitude, E loc , to that of the incident light, E0. The modeled parameters include w = 15 nm, P = 250 nm, n1 = 1.0, and n2 = 1.71, N = 1013 cm−2, at λ = (d) 31.1, (e) 27.5, and (f) 20.1 µm.

An alternate way to realize strong coupling and extreme field confinement with localized plasmons is by decreasing a BP sheet to finite nanoscale in-plane dimensions23. Finite size BP can add exotic edge states and lateral confinement in the main band gap48. For ideal edges and sub 10 nm scale structures, these would need to be addressed to take into account the quantum effects on the plasmonic resonance. However, atomic resolution scanning tunneling spectroscopy of exfoliated black phosphorus reveals only a trivial modification of the band gap at the sample edges49. In addition, monolayer black phosphorus nanoribbon widths below a few nanometers are required to significantly modify the band gap48,49. In this study we focus on properties of plasmonic responses for periodic nanoribbons with a minimum width of 100 nm and minimum gap of 25 nm. Due to this geometry, the spectral range of the plasmonic resonances studied here is substantially greater than the Fermi wavelength of BP nanoribbons48. Because of the aforementioned conditions, the quantum effects can be neglected. From here forward, we focus on properties of plasmonic responses for such reduced periodic arrays of BP ribbons. We have investigated these using a classical model with optical constants of infinite 2D monolayers of black phosphorus, Eq. (1) and Eq. (2).

A 3D schematic view of the structure designed for the study of localized surface plasmon polaritons (LSPPs) supported by BP is depicted in Fig. 1(b), with a corresponding 2D cross-sectional view shown in Fig. 1(c). The arrays of monolayer BP nanoribbons are periodically arranged in the x-y plane (z = 0). To confine the enhanced light, an optically thick gold reflector surface was added to the bottom of the model. In the z-direction, nanoribbons are separated from this reflector surface by a dielectric spacer with refractive index n2 = (ε2)1/2, (z < 0). A top dielectric medium with refractive index n1 = (ε1)1/2, (z > 0), covers the BP nanoribbon arrays. Data from Palick et al. for wavelength-dependent optical constants of gold were applied to the simulation50.

The electric field intensity distributions obtained from a finite element electromagnetic simulation51 are shown in Fig. 1(d–f) for the simulated illumination via plane wave at downward normal incidence for three different wavelengths. The width (w) of the BP ribbon was set to 150 nm, the period (P) to 250 nm, and the gap (g) between each ribbon was g = P − w = 100 nm. The ribbon width and period were selected so that the tunable range for wavelength went through the far-IR region of the electromagnetic spectrum. The ribbon was modeled to be surrounded by air (n1 = 1.0) on the top surface and a dielectric substrate (n2 = 1.71) of thickness 5 µm beneath. The dielectric substrate was made greater than λ/2 to avoid any coupling effects of the local fields near the BP ribbon and the gold surface. The field distribution reveals that the surface plasmon is highly confined at the edges of the nanoribbon and the confinement strength of the localized field is highly dependent on the excitation wavelength.

Strong field enhancement and localization of plasmon modes in the two-dimensional structure leads to enhanced spectral absorption depending on the shape and the selection of appropriate surrounding dielectric material52. Figure 2(a) displays simulated normal-incidence absorption spectra of the BP nanoribbons for w = 150 nm and P = 25 nm. Here, the top medium was set to the refractive index, n1, of air, and the absorptive substrate was swept from n2 = 1.0 to 3.32. Some of the selected indices of refraction, n2, values chosen match materials such as Al2O3 (1.71)53, KBr (1.43)54, PMMA (polymethyl methacrylate, 1.4555), PS (polystyrene, 1.50)55, and Si (3.32)50. Figure 2(b) is a plot of the resonant wavelengths (those with absorption peaks) versus the n2 values at which they occur, and Fig. 2(c) shows the absorption values at these peaks.

Calculated results showing the effects of varying n2 on the absorption spectrum with n1 held constant. (a) Simulated normal-incidence TM mode electric field absorption spectra for BP nanoribbons surrounded by air (n1 = 1.0) and different substrate materials with refractive indices, n2, and a BP electron density of N = 1013 cm−2. (b) Absorption peak resonant wavelength of the fundamental mode (m = 1) with respect to the refractive index of the substrate dielectric layer (n2). The red dots are from the finite-element method (FEM) simulations, and the blue dotes are calculated from the theoretical model described in Eq. (4). (c) Peak absorption amplitude as a function of n2.

As n2 is increased, the absorption peak position shifts to higher infrared wavelengths, Fig. 2(b), and broadens; and the amplitude generally decreases, as plotted in Fig. 2(c), indicating increased damping. Following grating theory, the peak absorption wavelengths, matching the resonant conditions of periodic BP nanoribbon, can be obtained from Eq. (4) under irradiation of light at normal incidence,

Here, λ p is the resonance wavelength of the BP plasmons, c is the speed of light, P is the period, ε0 is free space permittivity, e is the charge of a single electron, and m is a positive integer (m = 1, 2, 3, …) representing the order of the dispersion of the mode confinement diffraction. The resonance wavelengths of the analytical solution, Eq. (4), obtained via the periodic grating approach, do not consider the near-field interaction between the BP ribbons when the period is much smaller than the surface plasmon resonance wavelength, and disregards nonlocal effects. Due to coupling of plasmon waves between nearby BP nanoribbons and multiple anomalous reflections between the two edges of the ribbon, the reflected plasmon waves can form an interference process that incorporates a phase factor other than π. The surface plasmon at the resonance point undergoes constructive interference with the reflected wave between the edge, satisfying 2 wRe(kz1) + 2ϕ = 2 mπ56,57. Here, w is the ribbon width, ϕ is the reflection phase at the edge, and m is an integer for the peak resonance order. The value of ϕ can be obtained analytically by fitting the simulated data of a given ribbon surrounded by an arbitrary dielectric medium using Eq. (5),

Figure 2(b and c) illustrate the absorption resonance wavelength for different values of n2 obtained both via simulation and theoretical calculation via Eq (5). It is found that primary mode red shift linearly as the dielectric constant increases of the resonance wavelength consistent result in both theory and simulation. To further elucidate the effect of the surrounding dielectric, Fig. 3(a and b) show calculated and simulated absorption spectra for a range of n1 from 1 to 1.71 for fixed n2 = 1.71. The first-order phase factor was calculated using Eq. (5) for ranges between 0.41 π and 0.46 π, depending on the dielectric environment. Although similar situations are observed, the spectral broadening and resonance wavelength shifts are much weaker compared to the case of changing n2. The absorption peak wavelengths are only for dipolar modes and stay between 27% to 41% with the change of the top dielectric environment, Fig. 3(c). The resonance properties in the absorption spectra intensity and line width are also influenced by the optical loss in the BP ribbons, which is mainly characterized by the real part of the conductivity.

Calculated results showing the effects of varying n1 on the absorption spectrum with n2 held constant. (a) Simulated normal-incidence TM mode electric field absorption spectra for BP nanoribbons surrounded by different materials with refractive indices, n1, on a substrate with n2 = 1.7 (Al2O3) and a BP electron density of N = 1013 cm−2. (b) Absorption peak resonant wavelength of the fundamental mode (m = 1) with respect to the refractive index of the surrounding dielectric layer (n1). The red dots are from the FEM simulations, and the blue dotes are calculated from the theoretical model described in Eq. (4). (c) Peak absorption amplitude as a function of n1.

Mechanisms of Enhancing Absorption

The theoretical model predictions of enhanced infrared absorption and plasmonic resonance depend on the effective mass and density of carriers in the BP ribbons. The wavelength of the plasmon resonance in phosphorene nanoribbons scales proportionally with N−1/2, the same as in conventional semiconductors but contrary to graphene nanoribbons, which show a proportionality of N−1/4 45. According to Eq. (5), decreasing the anisotropic effective mass, which is dependent on the BP layer thickness, results in a blueshift and strong plasmon localization, while increasing the electron carrier density causes a redshift. The electron (carrier) density, related to the carrier mobility, is controlled by the chosen type of dielectric interface58,59, the introduction of doping, or gated-modulation21. To understand the tunability of the plasmon resonance and therefore the absorption wavelength in BP ribbons, it is instructive to inspect the significance of altering the conductivity and the ribbon geometry.

The armchair and zigzag directions of phosphorene are shown in Fig. 4(a and b), respectively. We would like to achieve higher absorption enhancement for light polarized in each direction. Here, optical constants of n1 = 1.0 and n2 = 1.71 and a reflective gold layer, as in Fig. 1(b), were considered. According to Eq. (5), one can tune the absorption spectra by changing the number density and the width of BP ribbons. To better quantitatively understand this tunability, absorption simulation results were obtained for the situation where the number density N = 5 × 1012, 7.5 × 1012, and 2.5 × 1013 cm−2, and the period was constant at P = 250 nm over a range of w from 100 nm to 225 nm. Figure 4(c and d) show plots of absorption spectra for light polarized in the armchair and zigzag directions, respectively, for the simulated range of w values for N = 2.5 × 1013 cm−2. The results for N = 5 × 1012 and 7.5 × 1012 cm−2 are provided in supplementary Fig. S1.

Comparison of the optical response of light polarized in the (a) armchair and (b) zigzag directions. Simulated absorption spectra for normal-incidence TM mode light polarized along the (c) armchair and (d) zigzag directions for different w. Here, n2 = 1.71, n1 = 1.0, N = 2.5 × 1013 cm−2, P = 250 nm, and w is swept from 100 to 225 nm.

The peak absorption wavelength position is highly sensitive to w due to the resonance condition of the localized surface plasmons, and it is also affected by the ribbon spacing, g(w) = P − w, due to strongly coupled resonances between neighboring ribbons. With a constant period of 250 nm, the gap between ribbons becomes small for large w, increasing the strength of the coupling effect. Shown in Fig. 4(c), the absorption is minimal for light polarized in the armchair direction when w is small (and the gap is large) ‒ due to weak plasmon localization and less field confinement at the edges. As w increases, so does the absorption, up to 0.83 for w = 225 nm, corresponding also to the smallest spacing value (g = 25 nm), since the coupling between neighboring ribbons increases. For the larger widths, the absorption peak also redshifts as w increases due to both width-dependent plasmon resonances and gap-dependent coupling between ribbons. In the zigzag direction, Fig. 4(d), the resonant wavelength redshifts from ~25 μm to 47 μm over the range w = 100 – 225 nm. In both the armchair and zigzag orientations, the peak shift shows that the ribbon width and spacing play important roles in tuning the BP ribbon plasmon resonance. The difference in the peak position and amplitude for the same values of w between zigzag and armchair directions is due to each atomic orientation having different anisotropic masses, which leads to different imaginary parts of the dielectric function; see Eq. (1) and (2).

The absorption strength in the zigzag direction increases from 0.14 to 0.48 for number density N = 2.5 × 1013 cm−2, compared to the absorption peak value of 0.13 reported by Liu and Aydin for N = 1013 cm−2 23. When one compares the peak wavelengths between N = 1013 cm−2 (Fig. 2) and N = 2.5 × 1013 cm−2 (Fig. 4) for w = 150, both armchair and zigzag directions show a blueshift of the absorption peak with increased carrier concentration, consistent with the prediction of Eq. (5). For carrier number density below N = 1013 cm−2 (see supplementary information), a width-dependent-dominant absorption is observed in the armchair direction and a weak resonance in the zigzag direction. Therefore, changing the electron number density, N, by using different substrates, doping the BP, or gating introduces a mechanism for tuning and amplifying the plasmonic resonance in BP.

Encapsulated BP Ribbons

Black phosphorus is highly reactive with oxygen; upon exposure to the environment, it degrades in a matter of minutes or hours21,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. Also, exposure to moisture causes significant distortion of its structure, causing the formation of porous regions that eventually decompose31,32,33,34,35,36,37. Encapsulation of BP with a thin dielectric sheet is essential for stability58,59. Therefore, we investigate how the dielectric sheet affects the edge plasmon modes in BP. Numerical simulations have been performed to demonstrate the electromagnetic response of phosphorene nanoribbons capped with two materials: a lossless dielectric, Al2O3, and a hyperbolic metamaterial hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) with optical constants obtained from60.

First, encapsulation via Al2O3 was studied, with the results shown in Fig. 5. Figure 5(a) shows the geometry of the model. For consistency with earlier discussions, we kept P = 250 nm, w = 150 nm, n1 = 1.0, and n2 = 1.71, the refractive index of Al2O3. Figure 5(b) shows the absorption spectra, corresponding to infrared plasmons, with the BP ribbon positioned at different distances (d) inside the substrate in the armchair direction. The peak wavelength shifts by approximately 1.5 μm as d increases from 0 to 10 nm inside the substrate, shown in detail in Fig. 5(c). The range of d is important to maintain the absorption amplitude so that it does not lead to a large change in the optical path length within the dielectric, potentially creating a standing wave. The small shift in wavelength and consistent peak absorption amplitude from Fig. 5 verify that dielectric layer encapsulation helps to conserve the main plasmon resonance properties. These small fine-tuned plasmon wavelength shifts due to a thin capping layer have interesting implications for light-matter interactions with regard to BP plasmon infrared nanoresonators, potentially for highly sensitive sensors.

Results for simulated patterned BP nanoribbons encapsulated by a dielectric buffered layer at different depths, d. (a) 2D cross-sectional schematic (b) Simulated absorption spectra for d = 0–10 nm and (c) resonance peak position as a function of d. Here, P = 250 nm, w = 150 nm, n1 = 1.0, N = 1013 cm−2, and n2 = 1.71 (Al2O3).

Next, we simulated hBN, anisotropic hyperbolic material, as an overlayered sheet for preserving the surface of the BP ribbons from degradation. hBN provides a superior protection layer for BP, mainly because it provides high mechanical strength, high thermal stability and chemical inertness59,61. In addition, the layer numbers (thickness) of hBN can be precisely controlled from monolayer to multilayer during the fabrication process through mechanical exfoliation or chemical vapor deposition methods62. Figure 6(a) and (b) depict the simulation design for BP ribbons encapsulated with hBN layers of different thickness, d. The armchair and zigzag directions are depicted again in Fig. 6(c and d), respectively. The simulated total absorption spectrum with d swept from 0 to 10 nm for TM polarized light in the zigzag and armchair directions are shown in Fig. 6(e and f), respectively.

(a) 3D and (b) 2D schematics of the simulated BP ribbons covered by a protective layer of hBN film of thickness d. (c) Armchair and (d) zigzag polarization directions as shown in Fig. 5. Simulated normal-incidence TM mode electric field absorption spectra for different thicknesses of hBN encapsulating BP for (e) armchair and (f) zigzag directions. Here, w = 225 nm, P = 250 nm, n1 = 1.0, n2 = 1.71, and N = 2.5 × 1013 cm−2.

The case of extremely small gaps between ribbons (w = 225 nm) was studied for N = 2.5 × 1013 cm−2. As shown in Fig. 6(e and f), the resonant wavelength shifts from 29 μm to 39 μm for armchair polarization, and 47 μm to 56 μm for zigzag. The gradual peak redshift is significantly larger than that of BP embedded in Al2O3. The absorption intensity is maintained between 80% and 90% in the armchair direction. The zigzag peak absorption drops gradually from 42% to 29% as the thickness of hBN increases, less than half of the values for armchair peak absorption. The presence of the hBN results in a strong localization of the field at the hBN/BP/dielectric interface in armchair direction and weak localization for zigzag. This is mainly due to the full electrical contact and strong interactions in the hybrid interaction that can arise between the ribbon plasmons and a thickness dependent phonon polariton mode that can arise in the hBN63. In addition, a noticeable broadening of the absorption peaks occurs for both polarization directions with the introduction of hBN on the BP ribbons.

Conclusion

In summary, we have investigated propagating surface plasmon properties of black phosphorus sheet- and edge-confined plasmons in surrounding dielectric structures for enhanced tunable absorption. Theoretical schemes of the plasmonic dispersion showed dependence on BP anisotropy, light polarization direction, and dielectric material. In particular, the confinement factor of SPPs has a strong effect, a factor of hundreds, on isolated BP and that increases as the refractive index of the surrounding media increases. Scaling of BP into the nanoribbon size leads to the formation of edge plasmons that trigger enhanced absorption. Simulation results of the spectral position and the absorption peaks can be adjusted both by the anisotropic nature of BP as well as by parameters such as the refractive index, ribbon size, ribbon spacing, and electron density; and the results have validated the theoretical prediction. Additionally, simulations of plasmon enhanced absorption behavior encapsulated the BP ribbon with either a protection nanolayer of lossless dielectric material or the metamaterial hBN to address the possibility of degradation through oxidation. The result shows further mechanisms of tuning resonance modes in infrared wavelengths due to hybridization of BP ribbon edge plasmon and the hyperbolic modes of hBN. The research achievements reveal a promising future for black phosphorene as a plasmonic material with properties that can give a viable platform to plasmon modulated optoelectronic devices across the infrared region of the spectrum.

Methods

Two-dimensional FEM simulations51 were performed to calculate electromagnetic field distributions and absorption spectra on nanoribbon cross-sections that assume infinite length in the y-direction. The 2D simulations can accurately approximate calculations of 3D structures so long as the length of the ribbon is large enough compared to the propagation and coupling length of the surface plasmon wavelengths. Periodic boundary conditions were applied along the left and right edges of the model (along the x-direction). Perfectly matched layers (PMLs) were added above and below this structure to eliminate the back scattering of electromagnetic waves from the model boundaries. A plane wave polarized in the x-direction illuminates the ribbons from above, normal to the substrate surface, in the TM case for the periodic structure. The top boundary was set as the input port and the bottom as the output. A non-uniform mesh was adopted, and the minimum mesh size inside the BP layer equals 0.01 nm, gradually increasing to 50 nm outside the dielectric region.

References

Barnes, W. L., Dereux, A. & Ebbesen, T. W. Surface plasmon subwavelength optics. Nature 424, 824–830 (2003).

Maier, S. A. & Atwater, H. A. Plasmonics: localization and guiding of electromagnetic energy in metal/dielectric structures. J. Appl. Phys. 98, 011101 (2005).

Ozbay, E. Plasmonics: merging photonics and electronics at nanoscale dimensions. Science 311, 189–193 (2006).

Atwater, H. A. The Promise of Plasmonics. Scientific American 296, 56–63 (2007).

Law, S., Yu, L., Rosenberg, A. & Wasserman, D. All-semiconductor plasmonic nanoantennas for infrared sensing. Nano Lett. 13, 4569–4574 (2013).

Pendry, J. B., Schurig, D. & Smith, D. R. Controlling electromagnetic fields. Science 312, 1780 (2006).

Low, T. & Avouris, P. Graphene Plasmonics for Terahertz to Mid-Infrared Applications. Acs Nano 8, 1086–1101 (2014).

Niu, J., Jun Shin, Y., Lee, Y., Ahn, J. H. & Yang, H. Graphene induced tunability of the surface plasmon resonance. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 061116 (2012).

Fei, Z. et al. Gate-tuning of graphene plasmons revealed by infrared nano-imaging. Nature 487, 82–85 (2012).

Yan, H. et al. Infrared spectroscopy of tunable Dirac terahertz magneto-plasmons in graphene. Nano Lett. 12, 3766–3771 (2012).

Fang, Z. et al. Active tunable absorption enhancement with graphene nanodisk arrays. Nano Lett. 14, 299–304 (2014).

Yan, H. et al. Damping pathways of mid-infrared plasmons in graphene nanostructures. Nat. Photonics 7, 394–399 (2013).

Niu, J. et al. Shifting of surface plasmon resonance due to electromagnetic coupling between graphene and Au nanoparticles. Opt. Express 20, 19690–19696 (2012).

Niu, J., Shin, Y. J., Lee, Y., Ahn, J. H. & Yang, H. Graphene induced tunability of the surface plasmon resonance. Appl Phys Lett 100(6), 1116–1120 (2012).

Li, L. et al. Black phosphorus field-effect transistors. Nat. Nanotechnology 9, 372–377 (2014).

Xia, F., Wang, H. & Jia, Y. Rediscovering black phosphorus as an anisotropic layered material for optoelectronics and electronics. Nature Commun. 5, 4458 (2014).

Liu, H. et al. Phosphorene: an unexplored 2D semiconductor with a high hole mobility. ACS Nano 8, 4033–41 (2014).

Wang, X. et al. Highly anisotropic and robust excitons in monolayer black phosphorus. Nat. Nanotechnology 10, 517–521 (2015).

Koenig, S., Doganov, R., Schmidt, H., Castro Neto, A. & Ozyilmaz, B. Electric field effect in ultrathin black phosphorus. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 103106 (2014).

Qiao, J., Kong, X., Hu, Z., Yang, F. & Ji, W. High-mobility transport anisotropy and linear dichroism in few-layer black phosphorus. Nat. Commun. 5, 4475 (2014).

Low, T. et al. Plasmons and Screening in Monolayer and Multilayer Black Phosphorus. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 106802 (2014).

Rodin, A. S. & Castro Neto, A. H. Collective modes in anisotropic double-layer systems. Phys. Rev. B 9, 075422 (2015).

Liu, Z. & Aydin, K. Localized surface plasmons in nanostructured monolayer black phosphorus. Nano Letters 16(6), 3457–3462 (2016).

Jiang, Y., Roldán, R., Guinea, F. & Low, T. Magneto-electronic properties of multilayer black phosphorus. Phys. Rev. B 92, 085408 (2015).

Jin, F., Roldán, R., Katsnelson, M. I. & Yuan, S. Plasmonics in strained monolayer black phosphorus. Phys. Rev. B 92, 115440 (2015).

Rodin, A. S., Carvalho, A. & Castro Neto, A. H. Strain-induced gap modification in black phosphorus. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 176801 (2014).

Yang, J. et al. Optical tuning of exciton and trion emissions in monolayer phosphorene. Light: Sci. Appl. 4, e312 (2015).

Li, P. & Appelbaum, I. Electrons and holes in phosphorene. Phys. Rev. B 90, 115439 (2014).

Engel, M., Steiner, M. & Avouris, P. Black Phosphorus Photodetector for Multispectral, High-Resolution Imaging. Nano Lett. 14, 6414–6417 (2014).

Viti, L. et al. Black phosphorus terahertz photodetectors. Adv. Mater. 27, 5567–5572 (2015).

Castellanos-Gomez, A. et al. Isolation and characterization of few-layer black phosphorus. 2D Materials 1, 025001 (2014).

Buscema, M. et al. Fast and broadband photoresponse of few-layer black phosphorus field-effect transistors. Nano Lett. 14, 3347–3352 (2014).

Ziletti, A., Carvalho, A., Campbell, D. K., Coker, D. F. & Castro Neto, A. H. Oxygen defects in phosphorene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 046801 (2015).

Favron, A. et al. Exfoliating pristine black phosphorus down to the monolayer: photo-oxidation and electronic confinement effects. arXiv preprint arXiv:1408.0345 (2014).

Sland, J. O., Steele, G. A., van der Zant, H. S. & Castellanos-Gomez, A. Environmental instability of few-layer black phosphorus. 2D Mater. 2, 011002 (2015).

Kim, J. S. et al. Toward air-stable multilayer phosphorene thin-films and transistors. Sci. Rep. 5, 8989 (2015).

Pei, J. et al. Producing air-stable monolayers of phosphorene and their defect engineering. Nat. Commun. 7, 10450 (2016).

Low, T. et al. Tunable optical properties of multilayer black phosphorus thin films. Phys. Rev. B 90, 075434 (2014).

Tea, E., & Hin C. Charge carrier transport and lifetimes in n-type and p-type phosphorene as 2D device active materials: an ab initio study, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, (18) 22706–22711 (2016).

Han, W. H., Kim, S., Lee, I. H. & Chang, K. J. Prediction of Green Phosphorus with Tunable Direct Band Gap and High Mobility. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8(18), 4627–4632 (2017).

Maier, S. A. Plasmonics : fundamentals and applications 29–30 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2007).

Matthes, L. et al. Optical properties of two-dimensional honeycomb crystals graphene, silicene, germanene, and tinene from first principles. New J. Phys. 16, 105007 (2014).

Asahina, H. & Morita, A. Band structure and optical properties of black phosphorus. Journal of Physics C: Solid State Physics 17, 1839 (1984).

Gao, W., Shu, J., Qiu, C. & Xu, Q. Excitation of plasmonic waves in graphene by guided-mode resonances. ACS Nano 6, 7806–7813 (2012).

Ju, L. et al. Graphene plasmonics for tunable terahertz metamaterials. Nat. Nanotech. 6, 630–634 (2011).

Grigorenko, A. N., Polini, M. & Novoselov, K. S. Graphene plasmonics. Nature Photon. 6, 749–758 (2012).

Du, L. et al. Edge-Reflection Phase Directed Plasmonic Resonances on Graphene Nano-Structures. Opt Express 22(19), 22689–22698 (2014).

Tran, V. & Yang, L. Scaling laws for the band gap and optical response of phosphorene nanoribbons. Phys. Rev. B 89, 245407 (2014).

Liang, L. et al. Electronic bandgap and edge reconstruction in phosphorene materials. Nano Lett. 14, 6400–6406 (2014).

Palik, E. D. Handbook of Optical Constants. Academic Press Inc., San Diego (1985).

COMSOL Multiphysics®, v. 5.0. www.comsol.com. COMSOL AB, Stockholm, Sweden.

Thongrattanasiri, S., Koppens, F. H. & de Abajo, F. J. G. Complete optical absorption in periodically patterned graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 047401 (2012).

Engel, M. et al. Light-matter interaction in a microcavity-controlled graphene transistor. Nat. Commun. 3, 906 (2012).

Li, H. H. Refractive index of alkali halides and its wavelength and temperature derivatives. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 5, 329–528 (1976).

Maharana, P. K., Jha, R. & Palei, S. Sensitivity enhancement by air mediated graphene multilayer based surface plasmon resonance biosensor for near infrared. Sens. Actuators. B: Chem. 190, 494–501 (2014). pp.

Velizhanin, K. A. Geometric universality of plasmon modes in graphene nanoribbon arrays. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 91, 125429 (2015).

Brar, V. W., Jang, M. S., Sherrott, M., Lopez, J. J. & Atwater, H. A. Highly confined tunable mid-infrared plasmonics in graphene nanoresonators. Nano Lett. 13, 2541–2547 (2013).

Viti, L. et al. Heterostructured hBN-BP-hBN Nanodetectors at Terahertz Frequencies. Adv. Mater. 28, 7390–7396 (2016).

Chen, X. et al. High-quality sandwiched black phosphorus heterostructure and its quantum oscillations. Nat. Commun. 6, 7315 (2015).

Caldwell, J. D. et al. Sub-diffractional volume-confined polaritons in the natural hyperbolic material hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Commun. 5, 5221 (2014).

Constantinescu, G. C. & Hine, N. D. Multipurpose Black-Phosphorus/hBN Heterostructures. Nano Lett. 16(4), 2586–2594 (2016).

Sinha, S., Takabayashi, Y., Shinohara, H. & Kitaura, R. Simple fabrication of air-stable black phosphorus heterostructures with large-area hBN sheets grown by chemical vapor deposition method. 2D Mater. 3, 035010 (2016).

Shi, Z. et al. Amplitude- and Phase-Resolved Nanospectral Imaging of Phonon Polaritons in Hexagonal Boron Nitride. ACS Photonics 2, 790 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded in part by the Doctoral Academy Fellowship through the University of Arkansas Graduate School. H.O.H.C acknowledges support from NSF award no. DMR-1610126.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, and data curation: D.T.D.; formal analysis, validation, writing, and editing: D.T.D., S.J.B., D.A.F., H.O.H.C., J.B.H.; Supervision, resource and funding acquisition: J.B.H.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Debu, D.T., Bauman, S.J., French, D. et al. Tuning Infrared Plasmon Resonance of Black Phosphorene Nanoribbon with a Dielectric Interface. Sci Rep 8, 3224 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21365-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21365-2

This article is cited by

-

A review: Biomedical applications of phosphorene, antimonene, and germanene-based 2D material/hydrogel complexes

Journal of Materials Science (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.