Abstract

Case reports and observational studies continue to report adverse events from medical errors. However, despite considerable attention to patient safety in the popular media, this topic is not a regular component of medical education, and much research needs to be carried out to understand the causes, consequences, and prevention of healthcare-related adverse events during neonatal intensive care. To address the knowledge gaps and to formulate a research and educational agenda in neonatology, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development invited a panel of experts to a workshop in August 2010. Patient safety issues discussed were the reasons for errors, including systems design, working conditions, and worker fatigue; a need to develop a “culture” of patient safety; the role of electronic medical records, information technology, and simulators in reducing errors; error disclosure practices; medicolegal concerns; and educational needs. Specific neonatology-related topics discussed were errors during resuscitation, mechanical ventilation, and performance of invasive procedures; medication errors including those associated with milk feedings; diagnostic errors; and misidentification of patients. This article provides an executive summary of the workshop.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In its seminal report, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) estimated that each year medical errors cause more deaths in hospitalized patients in the United Sates than the annual deaths caused by motor vehicle accidents, breast cancer, or AIDS-related illnesses (1). The IOM report described a four-tiered approach to address patient safety issues, with recommendation to adopting safety-related discoveries from other industries, such as aviation, nuclear power, and transportation.

Since the publication of the IOM report (1), patient safety issues have received more attention from the scientific community (2) and regulatory agencies (3–6). The US Food and Drug Administration has systems for reporting medication errors (3) and healthcare device-related errors (4,5). The World Health Organization (WHO) surgical safety checklists (7,8), “care bundles” to reduce healthcare-associated infections and childbirth injuries (9,10), and “extreme honesty,” and other transparent approaches for disclosures (11,12) are some of the example of progress in patient safety.

The US Federal government charged the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to conduct and support research on healthcare-related patient safety and to prepare regular reports. AHRQ established the Center for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety as the focal point for federally supported patient safety-related research and reporting (6).

Despite these, the concept of patient safety as an integral part of patient care has yet to permeate components of pediatric care, and patient safety has yet to become a standard part of the curriculum in medical, nursing, and pharmacy schools, as well as in residency and fellowship programs. Although case series and observational studies continue to report errors and patient harm (13–16) during neonatal care, systematic research is needed to understand the causes, consequences, and evidence-based methods to prevent neonatal intensive care-related errors.

To address these issues, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) organized a workshop on this topic and invited a panel of experts from diverse specialties (see acknowledgments) to address knowledge gaps and to propose a research agenda on patient safety issues. This article provides the executive summary of the workshop covering a brief review of generic issues on patient safety and unique patient safety issues in neonatology with suggestions for research and education.

Generic Issues in Patient Safety

Definitions.

Many common terms have acquired specific meanings in the field of patient safety, some of which are provided below to facilitate consistent usage in research and communication.

Patient safety is defined as freedom from accidental injury. By establishing operational systems and processes, one attempts to minimize the likelihood of errors and maximize the likelihood of preventing them (1).

Medical errors are those due to a failure of the planned action to be completed as intended or using a wrong plan of action to achieve the goal. They are often discovered when adverse events occur (1). Because most errors occur from failures in operational systems or unintended mistakes, one should avoid implying a negative connotation to the term “medical error” and avoid blaming a single person or a group of individuals.

Medication errors are defined, in part, as “any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the healthcare professional, patient, or consumer. … ” (3).

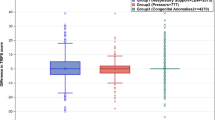

Adverse events are injuries and harm resulting from a medical interventions or lack thereof (1,3–6). Not all errors lead to adverse events, and not all adverse events are from medical errors. Sometimes, an error is recognized before patient injury, such as preventing a wrongly prescribed medicine from being administered, or treating it with an appropriate antidote. However, the larger the pool of errors, the higher are the chances for patient harm (Fig. 1) (17). Expected complications or side effects from therapeutic or diagnostic interventions are generally nonpreventable and, hence, are considered complications. Therefore, when analyzing an adverse event, one needs to determine whether the event was preventable or not. Only a small proportion of preventable adverse events occur from gross deviation from the accepted standards of care or the result of negligence. There is disagreement about which “events” need to be the focus for practice and care. Some authors favor targeting all errors for patient safety efforts (1,18), whereas others favor targeting only those that lead to patient harm (19).

Near misses are those errors that do not result in patient harm due to chance or timely intervention. Sometimes, they are also called close calls (1,20).

A diagnostic error is a missed, wrong, or delayed diagnosis, detected by later definitive tests, clinical findings, histopathology, or autopsy results (21).

Identification and Measurement of Errors and Adverse Events, and Research Designs

Many healthcare providers use retrospective data to detect and monitor medical errors and adverse events (2,21,22). These include medical record reviews, visual or videotaped observational studies, interviews or questionnaires, automated methods adopting trigger tools, analyses of administrative databases (e.g. patient safety indicators or ICD-9 codes), analyzing malpractice claims or autopsy data, and using data from mortality and morbidity conferences. Thus, most published studies have been observational to investigate the epidemiology of patient safety (1,2,21–25).

The purpose of the analyses generally dictates the method chosen. Analyses of voluntary reports and survey methods are quick and less expensive, but the collected data may be unreliable because of underreporting. Prospective surveillance systems are rigorous and provide reliable data but can be expensive and time consuming. The voluntary reporting of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs, now considered preventable adverse events) of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is a good example of a successful adverse event surveillance program at the national level. Other research methods include analyses of contributing factors (22), fishbone analyses (24), people versus system decision trees, and single-loop versus double-loop organizational learning from event reports. Studies are needed to assess the merits and limitations of such recent methods as “trigger tools” (22) in the context of neonatal patient safety.

All patient safety research needs to focus on human factors, systems, and culture. Randomized controlled trials and cluster trial designs can be adapted for patient safety research. Investigators must address issues of common sense, root causes, costs, ability to generalize results, and possible harm from “safety” measures themselves.

Causal and Contributory Factors of Errors and Preventable Adverse Events

The traditional approach to handling adverse events resulting from medical errors was to identify the individual(s) “responsible” for the errors and to take punitive actions. However, errors rarely occur from mistakes of a single individual. They are more likely to occur because of the culmination of multiple, related factors in the overall systems of care, such as the working conditions, human factors, and organizational culture. Blaming a single or a group of individuals for errors will likely prevent identification of the set of underlying events that led to the error.

Safety experts recommend a systems approach to understand the factors leading to errors and preventable adverse events (1,22–25), with the premise that humans are fallible and working conditions have major impact on the risk of errors. Some factors contributing to human fallibility include unavoidable imperfections in the cognitive processes (memory, vigilance, attention, concentration, and reasoning), fatigue, sleep deprivation, distractions, workload, stress and anxiety, and poorly designed devices to work with. While evaluating the reasons for errors, one must assess the range of factors that led to errors, including an assessment of the institutional business decisions, such as the architecture, logistical factors, human resource, and the type of equipment purchased.

The Swiss cheese model is a simple but powerful model to show how errors can reach patients and harm them despite existing safeguards and barriers. According to this model, like a slice of Swiss cheese, all safeguards in a healthcare organization contain “holes” or defects. If a system has too many defects, the chances are higher that an error may reach the patient causing a preventable adverse event (24).

Fatigue.

Many studies have revealed longer work hours, sleep deprivation, and fatigue as major factors contributing to errors and eliminating extended shifts (e.g. >16 h) improves safety (26–28). As efforts are made to reduce hours of work, research is needed to compare the effectiveness of best practices during sign-offs (hand-offs) of care that occur at shift transition (29,30). In addition, efforts should be made to find solutions to optimize the educational needs of the trainees without compromising the patient safety provisions.

Responding to Adverse Events, Disclosure, and Medical-Legal Issues

Safety culture as part of the healthcare mission statement.

Successful promotion of patient safety requires an organizational culture committed to patient safety that values “safety” far more than production and economic frugality (often disguised as efficiency) (1). Several nonmedical organizations have included safety as an utmost priority in their culture and mission statements. Nuclear power plants, the aeronautic industry, and air-traffic control industry are examples of high-reliability organizations. A good safety culture begets a safety climate in which workers are willing to report errors and near misses and feel safe from punitive retaliation. They will identify and report safety hazards, collaborate with the organization's hierarchy to adverse events, and consider patient safety as the most important component of their job (1,6).

Transparency and disclosures.

Patients and their families prefer transparency and open disclosure when a medical error or preventable adverse event occurs (31–34). Such disclosures are always ethically appropriate. An apology is an integral part of the disclosure conversation. Transparency and open disclosure also have the potential to reduce liability risk to institutions. Laws have been passed in many states to remove barriers to disclosure and apology (32).

Disclosures are better carried out by trained teams rather than by single individuals. Disclosure discussions are to be viewed as processes, not as risk management strategies. They need to link conversations about compensations and proposal of plans to prevent future errors and adverse events. A leading healthcare facility in the United States is practicing full disclosures and fair compensation, which has led to reductions in litigation costs, quicker resolution of the claims, and fewer claims and lawsuits (11). Additional research is required to improve disclosure practices and to understand the link between improved disclosures and patient safety.

Establishing learning systems and Patient Safety Organizations (PSO) programs.

After the 2005 Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act, the AHRQ created the PSO programs, established a network of Patient Safety Databases, and developed common formats to standardized reporting of patient safety events (35). The resulting analyses from these databases will be published in the annual issues of the National Health Quality and Disparities Reports.

AHRQ reports that 85 registered PSOs have been established since the Patient Safety Act (35). Although their activities are monitored and certified by AHRQ, none of the PSOs receives federal funding for their operations. They collect information on patient safety events from their client healthcare providers, analyze the data, and provide results with suggestions for improvements. Thus, PSOs can be valuable sources for not only collecting and evaluating objective patient safety data (e.g. using standardized NICU trigger tools) but also to improve patient safety across the NICUs. An independent national alliance of the PSOs further facilitates pooling of regional data into a larger database for additional analyses and feedback. Efforts to establish common formats for gathering and collection are underway. AHRQ recently made available common formats and standards, which can apply to all patient safety concerns (e.g. incidents, near misses, and unsafe practices).

At present, there are very few PSOs that deal with neonatal and perinatal issues exclusively. Such PSOs are urgently needed which can develop datasets that are relevant to pregnancy, labor, and delivery and neonatal intensive care issues, facilitating structured research in the field of perinatal patient safety.

Information technology (IT).

Recent advances in IT have led to several generations of commercial electronic health record systems; however, many technological barriers inhibit their widespread acceptance, including evidence of safety benefit from using health IT, the issues of compatibility across systems, meeting the training needs of the users, and assuring patient confidentiality (36,37).

Family involvement in patient safety.

There is a need to understand the contributions of patients and their families to prevent errors and to develop mitigation practices. For instance, family members often recognize missed actions during change of shifts and “hand-off” situations. A project by AHRQ is studying the types of information that consumers can provide, options for consumer reporting systems, possible infrastructures for consumer reporting, and benefits from such approaches (1,11,12,31).

Unique Patient Safety Issues in Neonatal Care

Although many generic patient safety issues are applicable to neonatology (38), some unique aspects of patient safety in the neonatal intensive have been recognized (13,14,39). These issues may require specific research strategies (9,10,40–43).

Patients in the NICU are very small and fragile, many with immature organ systems, and superimposed serious illness. Such infants are likely to receive complex care, including a large number of medications, and/or invasive procedures for diagnosis and treatment over an extended hospitalization. A single patient typically receives care from a team of experts. These increase the potential for errors and add additional demands for a higher threshold for device safety and efficacy, exemplifying the need for error-free devices and instruments. Given the narrow margin of safety, the patients are also more likely to suffer from harmful consequences of errors sooner. Because of their unique vulnerability, even minor errors can lead to devastating short- and long-term consequences. In large general hospitals, patient safety efforts are likely to be targeted toward adult patients or treatment units, with little appreciation for the unique needs of the NICUs and their patients.

A review of published literature shows nearly 100 original studies in the field of NICU patient safety and a few are cited here (13,36–38,40–46). Although the frequency of errors and adverse events are reported, only a few studies address the causal factors or interventions to prevent patient harm in neonatal care.

The domains of errors in the neonatal field.

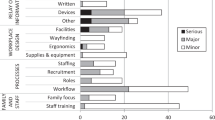

In Table 1, major domains of patient safety issues in the context of neonatal intensive care are listed. In neonatal and pediatric literature, the domain of medication errors is the most frequently reported compared with others (13,36–38,40–42). This may be because of the ease of recognizing and reporting medication errors and the availability of systems for reporting them to the FDA. There is also a longer history of monitoring for complications from medications.

Other unique types of errors in the NICU include feeding of the human milk to an infant from a wrong mother, inadvertent administration of human milk i.v., and wrong infant receiving a diagnostic test or treatment procedure due to errors in patient identification. Diagnostic errors seem to be the least studied domain in neonatal medicine.

Disclosure of errors in the NICU.

Challenges in the neonatal care environment include the complexities of communication and legal concerns. Effective strategies to prevent patient harm must include focused peer review, clinical quality improvement, and education. Consumers should be involved in training of the healthcare workers. Two-way communication and honesty are keys to advancing understanding (2,31,34).

Education in Patient Safety

Many programs in AHRQ and other federal agencies support research on new educational methods and patient and interdisciplinary education. The WHO Patient Safety Curriculum Guide encourages the teaching of patient safety topics to medical students and is being used worldwide.

There are a number of simulations of the clinical healthcare environment and multidimensional learning experiences. Coupling of education with clinical care itself needs to be carried out. Patient safety as part of the curriculum should be introduced throughout the continuum of medical education, and it should be interdisciplinary.

Trainees and patient safety.

Residents make errors at rates higher than those of senior providers, yet they need to develop expertise in patient care, along with a sense of autonomy. However, this should not take place at the expense of patient safety; even in the context of training residents and fellows, concern for patient safety should rank first. Adjusting work hours to optimize performance should be the goal; this may require redesigning the manpower needs of the healthcare system and developing different paradigms for fulfilling the training needs.

Research and Educational Agenda for Patient Safety in NICU

Improving patient safety in neonatal intensive care may also require approaches different from those used in other disciplines, thus necessitating a neonatology-specific research agenda. This is because neonates in the NICU have unique underlying disease types, and the treatment regimen and devices and instruments used in their care are often not developed specifically for use in sick infants. Moreover, the size and maturity of newborn infants make them uniquely susceptible for injury, even with the slightest deviation in safety practice. Thus, there should never be any room for error in the care of newborn infants.

Table 2 lists some of knowledge gaps identified by the panel along with potential research opportunities for the scientific community to consider addressing.

Summary and Conclusions

This article provides a summary of major topics of discussion at the NICHD workshop along with a plea to the scientific community to design innovative studies to understand the reasons for and to develop approaches to prevent adverse events in neonatal care. Developing a “patient safety culture” and incorporating it into the NICU mission statement should be a high-priority item, recognizing that it is a multifocus effort, beginning at the highest levels of the institutional leadership and permeating to the rest of the organization. Such a culture and commitment to the mission needs to establish a systematic approach to understand the causal pathways for errors and harm, evaluate the need for systems improvement, incorporate patient safety education into the standard training curriculum, and encourage reporting of errors without fear and retribution. These efforts should lead to learning from the analyses of errors and adverse events and make unsafe practices and patient harm rare events. Our patients deserve nothing less.

Abbreviations

- AHRQ:

-

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- IOM:

-

Institute of Medicine

- IT:

-

information technology

- PSO:

-

Patient Safety Organizations

REFERENCES

Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS 2000 To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press, Washington, DC.

Cochrane D, Taylor A, Miller G, Hait V, Matsui I, Bharadwaj M, Devine P 2009 Establishing a provincial patient safety and learning system: pilot project results and lessons learned. Healthc Q 12: 147–153

Medication Errors. Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/MedicationErrors/default.htm. Accessed March 25, 2011

CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services. Subchapter H—Medical devices 21 CFR part 803 medical device reporting. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart_803. Accessed March 25, 2011

Reporting Adverse Events (Medical Devices). Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/PostmarketRequirements/ReportingAdverseEvents/default.htm. Accessed March 25, 2011

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality website. Center for patient safety and quality improvement. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/about/cquips/cquipsmiss.htm. Accessed January 14, 2011

Senior K 2009 WHO Surgical Safety Checklist has value worldwide. Lancet Infect Dis 9: 211

Panesar SS, Carson-Stevens A, Fitzgerald JE, Emerton M 2010 The WHO surgical safety checklist—junior doctors as agents for chang. Int J Surg 8: 414–416

Toltzis P, Walsh M 2010 Recently tested strategies to reduce nosocomial infections in the neonatal intensive care unit. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 8: 235–242

DeVore S 2008 To protect little bundles of joy... we should try bundling care processes to reduce avoidable childbirth injuries. Mod Healthc 38: 24

Kachalia A, Kaufman SR, Boothman R, Anderson S, Welch K, Saint S, Rogers MA 2010 Liability claims and costs before and after implementation of a medical error disclosure program. Ann Intern Med 153: 213–221

Kachalia AB, Mello MM, Brennan TA, Studdert DM 2008 Beyond negligence: avoidability and medical injury compensation. Soc Sci Med 66: 387–402

Ramachandrappa A, Jain L 2008 Iatrogenic disorders in modern neonatology: a focus on safety and quality of care. Clin Perinatol 35: 1–34

Robertson AF, Baker JP 2005 Lessons from the past. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 10: 23–30

Arad I, Braunstein R, Ergaz Z, Peleg O 2007 Bruising at birth: antenatal associations and neonatal outcome of extremely low birth weight infants. Neonatology 92: 258–263

Jain S, Basu S, Parmar VR 2009 Medication errors in neonates admitted in intensive care unit and emergency department. Indian J Med Sci 63: 145–151

Hofer TP, Kerr EA, Hayward RA 2000 What is an error?. Eff Clin Pract 3: 261–269

McNutt RA, Abrams R, Arons DC 2002 Patient Safety Committee. Patient safety efforts should focus on medical errors. JAMA 287: 1997–2001

Layde PM, Cortes LM, Teret SP, Brasel KJ, Kuhn EM, Mercy JA, Hargarten SW 2002 Patient safety efforts should focus on medical injuries. JAMA 287: 1993–1997

Institute for Healthcare Improvement. When things go wrong. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/PatientSafety/SafetyGeneral/Literature/WhenThingsGoWrongRespondingtoAdverseEvents.htm. Accessed, January 14, 2011

Graber M 2005 Diagnostic errors in medicine: a case of neglect. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 31: 106–113

Thomas EJ, Petersen LA 2003 Measuring errors and adverse events in health care. J Gen Intern Med 18: 61–67

Vincent C 2003 Understanding and responding to adverse events. N Engl J Med 348: 1051–1056

Gupta P, Varkey P 2009 Developing a tool for assessing competency in root cause analysis. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 35: 36–42

Reason J 2000 Human error: models and management. BMJ 320: 768–770

Ulmer U, Miller WD, Johns MM 2009 Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. Committee on Optimizing Graduate Medical Trainee (Resident) Hours and Work Schedule to Improve Patient Safety. Institute of Medicine, The National Academies Press, Washington, DC.

The Committee on the Work Environment for Nurses and Patient Safety Institute of Medicine 2003 Keeping Patients Safe: Transforming the Work Environment of Nurses. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC.

Landrigan CP, Czeisler CA, Barger LK, Ayas NT, Rothschild JM, Lockley SW 2007 Effective implementation of work-hour limits and systemic improvements. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 33: 19–29

Lockley SW, Cronin JW, Evans EE, Cade BE, Lee CJ, Landrigan CP, Rothschild JM, Katz JT, Lilly CM, Stone PH, Aeschbach D, Czeisler CA 2004 Effect of reducing interns' weekly work hours on sleep and attentional failures. N Engl J Med 351: 1829–1837

Landrigan CP, Rothschild JM, Cronin JW, Kausha R, Burdick E, Katz JT, Lilly CM, Stone PH, Lockley SW, Bates DW, Czeisler CA 2004 Effect of reducing interns' work hours on serious medical errors in intensive care units. N Engl J Med 351: 1838–1848

King A, Daniels J, Lim J, Cochrane DD, Taylor A, Ansermino JM 2010 Time to listen: a review of methods to solicit patient reports of adverse events. Qual Saf Health Care 19: 148–157

McDonnell WM, Guenther E 2008 Narrative review: do state laws make it easier to say “I'm sorry?”. Ann Intern Med 149: 811–816

Goldsmith JP 1989 Medical-legal concerns of providing high risk neonatal care in an HMO. HMO Pract 3: 210–215

Vincent C, Taylor-Adams S, Chapman EJ, Hewett D, Prior S, Strange P, Tizzard A 2000 How to investigate and analyze clinical incidents: clinical risk unit and association of litigation and risk management protocol. BMJ 320: 777–781

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Organizations. Available at: http://www.pso.ahrq.gov/listing/alphalist.htm. Accessed, January 14, 2011

Porter SC, Kaushal R, Forbes PW, Goldmann D, Kalish LA 2008 Impact of a patient-centered technology on medication errors during pediatric emergency care. Ambul Pediatr 8: 329–335

Kaushal R, Kern LM, Barrón Y, Quaresimo J, Abramson EL 2010 Electronic prescribing improves medication safety in community-based office practices. J Gen Intern Med 25: 530–536

Raju TN, Kecskes S, Thornton JP, Perry M, Feldman S 1989 Medication errors in neonatal and paediatric intensive-care units. Lancet 2: 374–376

Donowitz LG, Marsik FJ, Fisher KA, Wenzel RP 1981 Contaminated breast milk: a source of Klebsiella bacteremia in a newborn intensive care unit. Rev Infect Dis 3: 716–720

Kaushal R, Goldmann DA, Keohane CA, Abramson EL, Woolf S, Yoon C, Zigmont K, Bates DW 2010 Medication errors in paediatric outpatients. Qual Saf Health Care 19: e30

Lemer C, Bates DW, Yoon C, Keohane C, Fitzmaurice G, Kaushal R 2009 The role of advice in medication administration errors in the pediatric ambulatory setting. J Patient Saf 5: 168–175

Kaushal R, Bates DW, Abramson EL, Soukup JR, Goldmann DA 2008 Unit-based clinical pharmacists' prevention of serious medication errors in pediatric inpatients. Am J Health Syst Pharm 65: 1254–1260

Powers RJ, Wirtschafter DW 2010 Decreasing central line associated blood stream infection in neonatal intensive care. Clin Perinatol 37: 247–272

Yeager SB, Horbar JD, Greco KM, Duff J, Thiagarajan RR, Laussen PC 2006 Pretransport and posttransport characteristics and outcomes of neonates who were admitted to a cardiac intensive care unit. Pediatrics 118: 1070–1077

Gray JE, Ursprung R, Edwards WH, Horbar JD, Nickerson J, Plsek P, Shiono PH, Suresh G, Goldman DA 2006 Patient mis-identification in the NICU: quantification of risk. Pediatrics 117: e43–e47

Ursprung R, Gray JE, Edwards WH, Horbar JD, Nickerson J, Plsek P, Shiono PH, Suresh G, Goldman DA 2005 Real time patient safety audits: improving safety every day. Qual Saf Health Care 14: 284–289

Acknowledgements

We thank the following speakers, discussants, and participants at the NICHD workshop on patient safety: Stephanie Archer, M.S., Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), Bethesda, MD; James B. Battles, Ph.D., Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); George T. Blike, M.D., Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH; Jeff Brady, M.D., M.P.H., AHRQ, Rockville, MD; Gilbert Burckart, Pharm.D., US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Silver Spring, MD; Judith U. Cope, M.D., M.P.H., FDA, Silver Spring, MD; Steven M. Donn, M.D., University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, MI; Steven Fox, M.D., S.M., M.P.H., AHRQ, Rockville, MD; Thomas H. Gallagher, M.D., University of Washington, Seattle, WA; George Giacoia, M.D., NICHD, Bethesda, MD; Michael Giuliano, M.D., M.E., M.H.P.E., University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Hackensack, NJ; James Gray, M.D., M.S., Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA; Darryl T. Gray, M.D., Sc.D., FAHA, AHRQ, Rockville, MD; Alan Guttmacher, M.D., NICHD, Bethesda, MD; Martin J. Hatlie, J.D., Partnership for Patient Safety, Chicago, IL; Amy Helwig, M.D., M.S., AHRQ, Rockville, MD; Rosemary D. Higgins, M.D., NICHD, Bethesda, MD; Rainu Kaushal, M.D., M.P.H., Weill Cornell Medical College, NY, NY; Mahin Khatami, Ph.D., National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD; Christopher P. Landrigan, M.D., M.P.H., Children's Hospital Boston and Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA; Stuart Levine, Pharm.D., Institute for Safe Medication Practice, Horsham, PA; Joann Petrini, Ph.D., M.P.H., Danbury Hospital, Danbury, CT; Tonse N.K. Raju, M.D., NICHD, Bethesda, MD; William Rodriguez, M.D., Ph.D., FDA, Silver Spring, MD; Cathelijne Snijders, M.D., Ph.D., Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands; Roger F. Soll, M.D., Fletcher Allen Health Care, Burlington, VT; W. Michael Southgate, M.D., Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC; Michael E. Speer, M.D., Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX; Catherine Y. Spong, M.D., NICHD, Bethesda, MD; Gautham Suresh, M.D., D.M., M.S., Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH; Eric Thomas, M.D., M.P.H., University of Texas Medical School at Houston, Houston, TX; and Yan Xiao, Ph.D., Baylor Health Care System; Dallas, TX.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Raju, T., Suresh, G. & Higgins, R. Patient Safety in the Context of Neonatal Intensive Care: Research and Educational Opportunities. Pediatr Res 70, 109–115 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182182853

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182182853

This article is cited by

-

“What’s in a name?” Identification of newborn infants at birth using their given names

Journal of Perinatology (2022)

-

Standardizing premedication for non-emergent neonatal tracheal intubations improves compliance and patient outcomes

Journal of Perinatology (2022)

-

A study of medication errors during the prescription stage in the pediatric critical care services of a secondary-tertiary level public hospital

BMC Pediatrics (2020)

-

Impact of patient handover structure on neonatal perioperative safety

Journal of Perinatology (2019)

-

Prospective, controlled study of an intervention to reduce errors in neonatal antibiotic orders

Journal of Perinatology (2015)