Key Points

-

In nephrology and transplant medicine, many opportunities for vaccination and protection against infection are missed

-

As immunogenicity is generally greater before transplantation, early in the course of renal disease—or at least before transplantation—is the optimal window of opportunity for vaccination

-

Delaying vaccination for the first 6–12 months after transplantation (or repeating vaccines given early) might result in higher rates of protection; nonetheless, influenza vaccine should be given in season

-

The reported impact of individual immunosuppressive agents on vaccine responses varies between studies; overall, a lower immunosuppressive protocol is more likely to result in clinical protection

-

Although some concern about increased HLA sensitization after vaccination exists, clinical data does not suggest harm; non-live vaccines appear immunogenic, protective and safe

-

Future research is needed into the impact of immunosuppressive protocols on vaccination responses, optimal timing after transplantation, dosing regimens, intradermal administration, clinical protection, use of adjuvants, safety and adverse effects

Abstract

Many transplant recipients are not protected against vaccine-preventable illnesses, primarily because vaccination is still an underutilized tool both before and after transplantation. This missed opportunity for protection can result in substantial morbidity, graft loss and mortality. Immunization strategies should be formulated early in the course of renal disease to maximize the likelihood of vaccine-induced immunity, particularly as booster or secondary antibody responses are less affected by immune compromise than are primary or de novo antibody responses in naive vaccine recipients. However, live vaccines should be avoided in immunocompromised hosts. Although some concern has been raised regarding increased HLA sensitization after vaccination, no clinical data to suggest harm currently exists; overall, non-live vaccines seem to be immunogenic, protective and safe. In organ transplant recipients, some vaccines are indicated based on specific risk factors and certain vaccines, such as hepatitis B, can protect against donor-derived infection. Vaccines given to close contacts of renal transplant recipients can provide an additional layer of protection against infectious diseases. In this article, optimal vaccination of adult transplant recipients, including safety, efficacy, indication and timing, is reviewed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vaccination has saved more lives than any other medical intervention; protection against infection is generally effective, durable and safe. Although kidney transplant recipients are more vulnerable to infection than the general population, substantial numbers of these patients remain unvaccinated—both before and after transplantation—and are, therefore, unprotected against vaccine-preventable illnesses. This missed opportunity for protection can result in serious infection, graft loss and mortality. Optimization of vaccination should occur as early as possible in the course of renal disease to maximize the likelihood of vaccine-induced immunity. Early vaccination is particularly important because secondary antibody responses are less affected by immune compromise than are primary or de novo antibody responses in naive vaccine recipients. Here, I describe the safety, efficacy, need for and timing of vaccination in adult transplant recipients, including discussion of specific vaccines and indications.

Necessary vaccinations

To avoid vaccine-preventable illness, all adults should receive routine vaccinations (Box 1). Certain additional vaccines are indicated for immunocompromised hosts, patients with certain medical conditions and individuals with additional potential exposures (as suggested in guidelines from the United States Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices,1 WHO,2 American Society of Transplantation Infectious Disease Community of Practice3 and the Infectious Diseases Society of America4).

Organ transplant recipients need appropriate vaccinations before and after transplantation. The 2009 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) clinical practice guidelines on the monitoring, management and treatment of kidney transplant recipients recommends that these patients are given approved, inactivated vaccines according to the recommended schedules for the general population, with the exception of hepatitis B vaccination (for which they recommend a modified protocol).5 In general, transplant recipients should receive annual influenza vaccine, routine pneumococcal and tetanus–diphtheria–pertussis vaccine updates as per guidelines1,2 and additional vaccines given periodically (Table 1). Certain other vaccines are recommended based on specific risk factors (for example, meningococcal vaccine before splenectomy or use of eculizumab).

Lack of proper vaccination is a major missed opportunity for protection. For example, US data show that in 2011, pneumococcal vaccination coverage among high-risk adults aged 19–64 years (smokers and patients with diabetes mellitus, asthma, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, renal disease, coronary heart disease, angina, heart attack, other heart conditions or cancer) was 20.1% overall.6 Unsure of safety and need, many physicians overlook the opportunity to vaccinate patients with kidney disease. Proper pretransplant vaccination enhances safety and could even expand the donor pool (for example, hepatitis B vaccination might enable a patient to receive an organ from a donor with prior hepatitis B exposure).

Specific circumstances are indications for specific vaccines. For example, prior or scheduled splenectomy necessitates routine meningococcal, pneumococcal and Haemophilus influenzae vaccines, with periodic updates. The complement inhibitor eculizumab, which is increasingly used in the organ-transplant setting, has been associated with meningococcal disease;7 two doses of meningococcal vaccine should be given prior to transplantation when eculizumab use is anticipated. Veterinarians and other individuals with substantial exposure to at-risk animals should be vaccinated against rabies and be made aware of the potential exposure and disease transmission from live vaccines, such as Bordetella bronchiseptica—the aetiologic agent of kennel cough. Those with plans for international travel after transplantation should be assessed in a travel medicine clinic that is familiar with transplant recipients.

Vaccination safety

Vaccines save lives. The risks of infection for unprotected and susceptible transplant recipients might be much greater than the largely theoretical risks of vaccination. A retrospective analysis of 36,966 patients on dialysis in 2005–2006 demonstrated that those who had received both influenza and pneumococcal vaccines had a significantly lower odds ratio for mortality than those who had received only one of these vaccines.8

Numerous types of vaccines are available. Injectable influenza and polio vaccines as well as hepatitis A vaccine are inactivated viruses, whereas tetanus and diphtheria vaccines are inactivated bacterial toxoids. The main difference between polysaccharide pneumococcal (Pneumovax®, Merck, USA) and meningococcal (Menomune®, Sanofi Pasteur, USA) vaccines and the corresponding conjugate vaccines (Prevnar13® [Wyeth, USA], Menactra® [Sanofi Pasteur, USA] and Menveo® [Novartis Vaccines, USA]) is the addition of a diphtheria protein carrier for enhanced immunogenicity. Virus-like particle vaccines include hepatitis B and human papillomavirus, which comprise surface proteins assembled in a particle that mimics the coat of the natural viral agent. Attenuated viral vaccines include influenza, varicella (and zoster), measles, mumps, rubella, rotavirus, yellow fever and oral polio.

To the best of current knowledge, all non-live vaccines are safe for organ transplant recipients. The KDIGO guidelines state that “little or no harm has been described with the use of licensed, inactivated vaccines in [kidney transplant recipients]”.5 They report that most vaccines produce an antibody response (albeit diminished) in immunocompromised individuals and conclude that “the potential benefits outweigh the harm of immunization with inactivated vaccines in [kidney transplant recipients].”

Live vaccines, including the viral vaccines noninjectable live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV), varicella, zoster, measles, mumps, rubella, rotavirus, yellow fever, oral polio and vaccinia (smallpox) as well as the bacterial vaccines Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) and oral typhoid fever, could cause disseminated disease and are generally contraindicated in transplant recipients (Box 1 and Table 1).4,5,9 Whenever possible, these live vaccines should be administered prior to transplantation, assuming no active or recent exogenous immunosuppression, with at least a 1 month 'washout' period before transplantation. Although most vaccines are contraindicated with any immunosuppression, administration of varicella and zoster vaccine can be done safely in patients on low-dose immunosuppression (prednisone or azathioprine).10,11 Nonetheless, multidrug immunosuppression after renal transplantation is a contraindication to use of these vaccines.

Immunostimulatory agents including alum and squalene are sometimes used to augment the immune response to vaccination by increasing the local immune response. Concern has been raised as to whether such adjuvants might augment the risk of organ rejection in transplant recipients.12 Guidelines for influenza vaccination summarize the current experience with adjuvants; overall, they cannot yet be recommended or proscribed.13 Transplant programmes might elect to use nonadjuvanted vaccines but adjuvanted vaccines should be used if no alternative is available.12 A study that evaluated the efficacy of the squalene-based immunological pandemic influenza vaccine AS03 in kidney transplant recipients demonstrated safety with no effect on graft function and fewer adverse reactions in these patients than in a control group of healthy untransplanted individuals.14 The reported response rate (measured using a haemagglutination assay and confirmed by microneutralization) in kidney transplant recipients of 83%, compared with 87% in controls, suggested reasonable immunogenicity in this population.

Multiple studies have shown occasional, fairly low-level de novo anti-HLA antibody formation of unclear clinical significance after influenza vaccination.15,16,17 A trial of influenza vaccine in 212 transplant recipients indicated differences in development of anti-HLA antibody production after vaccination in three participants (1.4%) with no clinical consequences.17 Until such antibody formation is shown to be of clinical significance, standard vaccination should be continued. In a retrospective cohort study of 51,730 adults who underwent first kidney transplantation between January 2000 and July 2006, 9,678 (18.7%) patients had Medicare claims for influenza vaccination in the first year after transplantation; influenza vaccination was associated with a lower risk of subsequent allograft loss and death.18 Although this study did not evaluate serological response to vaccination, the data indicates that vaccines should not be withheld because of concerns that they might adversely affect allograft function.

Factors affecting response to vaccination

Solid-organ transplant recipients tend to have a less robust response to vaccination than normal hosts because of their immunosuppression and—potentially—their comorbidities (such as diabetes mellitus).19 Whether this diminished immunological response (which is usually serological, that is, reduced antibody titre) correlates with true diminished protection has not been well studied; the necessary large clinical trials would be very challenging to perform. The degree to which the response is impaired varies with the type of vaccine, recipient age and type of organ transplanted. In addition, serological responses often wane more rapidly in solid-organ transplant recipients that in the general population;20 thus, these patients might need more frequent booster doses. Whether serological responses should be checked on a regular basis, with subsequent revaccination if required, or whether routine revaccination should be performed has not been studied and is currently left to the discretion of the treating physician. As obtaining serological data requires two visits to the clinic, it might be easier to assume diminished protection and revaccinate periodically, perhaps on a somewhat accelerated schedule compared with that suggested for the general population.

Optimizing the timing of vaccination might help to maximize immunological responses in transplant recipients. In the initial post-transplant phase, these responses are generally reduced (or even absent) as a result of intense immunosuppressive therapy. Many transplant programmes, therefore, defer vaccination of patients until a few months after transplantation; the KDIGO guidelines suggest avoiding vaccinations (except influenza vaccine) for 6 months following kidney transplantation.5 Unfortunately, very few trials have formally analysed optimal timing with respect to vaccination responses. Organ transplant recipients are excluded from the majority of vaccine trials for several months after transplantation. Two studies have reported lower antibody titres in patients vaccinated within 6 months of kidney transplantation than in those vaccinated after this period.17,21 In the first study, 19 of 53 patients received a donor kidney ≤6 months before vaccination with standard inactivated influenza vaccine.21 When compared with normal hosts, the reduced vaccination response in these recipients was more marked than in those who underwent transplantation >6 months after vaccination. In the second study, which included 212 adult solid-organ transplant recipients, vaccine responses to standard intramuscular influenza vaccine (measured by haemagglutination inhibition assay) were reported in 53.2% of patients vaccinated ≥6 months after transplantation, compared with only 19.2% of those who were vaccinated <6 months after transplantation (P = 0.001).17

An earlier analysis of influenza vaccine responses in recipients of solid organ transplants (n = 68) reported no significant difference in mean time after transplantation in the vaccine responder and nonresponder groups.22 In a cohort of liver transplant recipients (n = 51), however, influenza vaccine responses correlated to time after transplantation: one of seven patients (14%) vaccinated <4 months after transplantation, six of nine (67%) patients vaccinated 4–12 months after transplantation and 30 of 35 (86%) patients vaccinated 12 months after transplantation showed an antibody response to the H1 strain. Overall, >55% of patients who were vaccinated 4–12 months after liver transplantation had adequate antibody seroconversion titres against the H1, H3 and B strains of the influenza vaccine, suggesting this might be a reasonable period to initiate vaccination.23 A trial of human papilloma virus vaccine in 47 organ transplant recipients also found a diminished serological response when the vaccine was administered within the first 6 months after transplantation compared with later administration.24

As robust data to guide optimal timing of vaccination is lacking, individual transplant programmes have developed their own protocols. A 2009 survey that included 239 US transplant programmes found that 42% gave influenza vaccine at <3 months, 43% at 3–6 months, 13% at 6–12 months and 3% at >12 months following kidney transplantation.25 The American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice guidelines suggest restarting influenza vaccination 3–6 months after the procedure.26 In the case of pandemic H1N1, vaccination ≥1 month after transplantation is recommended.12 The KDIGO guidelines state that patients who are at least 1-month post-transplant should receive influenza vaccination prior to the onset of the annual influenza season, regardless of their immunosuppression status.5 Further studies are needed to determine the ideal timing of influenza vaccination after solid-organ transplantation to optimize the protection of vulnerable transplant recipients against this common infection.

Specific immunosuppressive agents and their impact on vaccination responses have been evaluated in multiple studies with variable results. Treatment with mycophenolate mofetil sometimes results in an attenuated vaccine response. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors might also inhibit the immune response to influenza vaccine in solid-organ transplant recipients.27 Given the risk of rejection and subsequent need for high-dose immunosuppression, reducing immunosuppression to improve vaccination response is generally not recommended.

Multiple vaccines can be administered during a single clinic visit. When possible, in patients with functional or anatomic asplenia, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) and Menactra® meningococcal conjugate vaccine should be administered at least 4 weeks apart, as Menactra® is thought to interfere with the antibody response to PCV.9 Unlike live vaccines, inactivated antigens are generally not affected by circulating antibodies so can be administered before, after or at the same time as the antibody-containing products.9 Simultaneous administration of antibody (in the form of immunoglobulin) and vaccine is recommended for postexposure prophylaxis of certain diseases, such as hepatitis B, rabies and tetanus.9 Vaccines could be given at many office visits before or after transplantation. Some of the more common but invalid contraindications to vaccination include mild illnesses, non-anaphylactic allergies or reactions and a family history of adverse reactions.9

Unfortunately, renal transplant recipients in whom vaccination is contraindicated, and who remain unprotected against certain infections, such as varicella, measles and yellow fever, might be exposed to these diseases and need an additional modality for protection (that is, antiviral agents, immunoglobulins and avoidance of areas of disease outbreak). Such situations have not been systematically studied.

Vaccines

Hepatitis B

All patients with kidney disease should undergo hepatitis B vaccination,2 ideally before starting dialysis when the vaccine is more likely to provide immunity. However, the vaccine can be given to patients on dialysis or kidney transplant recipients. The KDIGO guidelines recommend hepatitis B vaccination (ideally before transplantation) and assessment of hepatitis B surface antibody titres 6–12 weeks after completing the vaccination series and annually thereafter.5 Patients should be revaccinated if the antibody titre is <10 U/ml.5 Multiple studies have shown a greater probability of seroconversion with higher-dose vaccination (20 μg or 40 μg instead of 10 μg), which is recommended for those on dialysis1 and might also be preferable after transplantation. Although unstudied, an accelerated vaccination series (3–4 monthly vaccinations) can be given to those for whom transplantation in the near future is anticipated. A serological response to vaccination (assessed by measuring hepatitis B surface antibody) should be evaluated ≥1 month after the last vaccine dose is given, especially if the kidney donor has an increased risk of transmitting hepatitis B, as this result might alter the prophylaxis plan.28

Influenza

All kidney transplant recipients should undergo annual influenza vaccination with injectable vaccine (the live viral vaccine intranasal LAIV should not be given). Although not as protective in these patients as in healthy individuals, the vaccine is generally reasonably and adequately protective. Quadrivalent influenza vaccine was released for the 2013–2014 season. Although no safety data in transplant recipients is currently available, this vaccine is expected to be safe and to provide additional protection against influenza B, which accounts for roughly a tenth of overall influenza activity. A trial of high-dose intradermal influenza vaccine compared with standard intramuscular vaccine in 212 organ transplant recipients, showed that seroconversion to more than one antigen was slightly higher in the intradermal cohort at 51.4%, compared with 46.7% in the intramuscular group (P = 0.49).17 Data are currently insufficient to recommend use of high-dose, booster dose (within the same season), adjuvanted or intradermal influenza vaccine in lieu of standard intramuscular vaccine.13 In certain circumstances, such as in the settings of recent transplantation or potent immunosuppression, such techniques could be considered. Many programmes begin administering the influenza vaccine <3 months after transplantation25 and within 1 month of transplantation in the setting of pandemic or epidemic disease.12

Pneumococcal

Routine pneumococcal vaccine is indicated for all kidney transplant recipients and patients with renal disease. In transplant recipients, the estimated risk of developing invasive pneumococcal disease is 28–36 per 1,000 patients per year, a rate much higher than the estimated incidence in the general population.29 The main vaccines currently on the market are the polysaccharide 23-valent vaccine (PPSV23 or Pneumovax®) and the conjugate vaccine (PCV13 or Prevnar®). Adults (aged ≥19 years) with immunocompromising conditions (including chronic renal failure and nephrotic syndrome), who have not previously received PCV13 or PPSV23 should receive a single dose of PCV13 followed by a dose of PPSV23 at least 8 weeks later.30 Those who have previously received ≥1 dose of PPSV23 should receive a dose of PCV13 ≥1 year after the last PPSV23 dose was given. For adults who require additional doses of PPSV23, the first should be given no sooner than 8 weeks after PCV13 and at least 5 years after the most recent dose of PPSV23. In immunocompromised patients a second dose of PPSV23 5 years after the initial dose is recommended.1,30

Using a Markov model, a cost-effectiveness analysis of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in immunocompromised adults showed that a single dose of PCV13 compared to no vaccination cost US$70,937 per quality adjusted life year (QUALY) gained, whereas vaccination according to current recommendations with one dose of PCV13 and one dose of PPSV23 cost $136,724 per QALY.30 These data suggest that a single dose of PCV13 is more cost-effective in immunocompromised individuals than a single dose of PPSV23, and is less economically burdensome than current recommendations involving two vaccines, depending on life expectancy and vaccine effectiveness.31 Whether new guidelines for sequential vaccination in immunocompromised patients1,30 will lead to an improvement in clinical protection remains to be studied.

Similar to other vaccines, pneumococcal vaccine responses seem to wane more rapidly in transplant recipients than in normal hosts.32 In renal transplant recipients, a significant decline of vaccine response 3 years after vaccination has been reported; use of conjugate vaccine did not improve the durability of response.20 Repeat vaccinations might augment immunity, although whether multiple doses over many years is protective has not been not well studied in this population and merits further evaluation.

Varicella and zoster

Varicella and zoster are live viral vaccines that should be given prior to transplantation when indicated (varicella to all nonimmune patients and zoster to patients aged ≥60 years).1 They are not recommended in adults after transplantation. Some data suggest that paediatric patients on low-dose immunosuppression after liver transplantation can safely and effectively undergo varicella vaccination,33,34 but this finding has not been documented in adult transplant recipients and the vaccine is contraindicated in these patients.3,4,5 Seronegative renal transplant recipients with exposure to varicella can be given acyclovir, valacyclovir or famciclovir for prophylaxis, varicella-specific immunoglobulin can also be used.35,36 In addition, intravenous immunoglobulin can be used when other modalities are not available; although unstudied, pooled antibodies might provide some protection.36

Seropositive solid-organ transplant recipients are immune to de novo varicella disease but tend to develop zoster at much higher rates than the general population.36 The zoster vaccine is a high dose of the live attenuated Oka varicella strain that is used in the varicella vaccine, with a minimum of 19,400 plaque-forming units compared with a minimum of 1,350 plaque-forming units in varicella vaccine. In a large trial of older adults (≥60 years) zoster vaccine reduced the incidences of zoster by 51% and post-herpetic neuralgia by 67%.37 Whether use of the zoster vaccine before transplantation provides long-term protection remains to be determined; however, use of this vaccine at least 1 month before transplantation is recommended when indicated.36 Household members of transplant recipients can be vaccinated with either vaccine.3

Tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis

Tetanus and diphtheria are rare in developed countries as a result of widespread vaccination. Pertussis, however, has had a recrudescence in the past decade. All potential kidney transplant recipients and all patients who have already received a donor kidney should be vaccinated against these diseases using a triple combination vaccine as per guidelines.1 Transplant recipients at high risk include those who work in health care or are caregivers of infants and small children. As immunity to tetanus and diphtheria wanes significantly during the first 3 years after paediatric kidney transplantation,38 booster doses of vaccine should probably be given to these patients at a somewhat more frequent interval than in healthy children. The exact interval is not known, but I tend to repeat these vaccinations after 5–7 years, especially in those who are at high risk of pertussis.

Meningococcal

Meningococcal vaccination is recommended for patients with functional or true asplenia, complement deficiency, HIV infection or other immunocompromising conditions.1 The complement inhibitor eculizumab, which is increasingly used in transplantation, causes complement deficiency and is associated with an increased risk of meningococcal disease.7 The currently commercially available quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccines cover serogroups A, C, Y and W135 but not serogroup B. As a two-dose series (at least 8 weeks apart) with a booster dose every 5 years is recommended for patients with HIV or splenectomy,1 it would seem logical that transplant recipients should receive the same regimen. Even with prior single vaccination, meningococcal sepsis with strain W135 has been reported after eculizumab therapy, suggesting a need for two-dose series vaccination prior to transplant and/or chemoprophylaxis.7 Our group vaccinates potential transplant recipients with substantial allosensitization (indicated by elevated panels of reactive antibodies) prior to transplantation in preparation for possible eculizumab use.

Measles, mumps and rubella

Although most adults are immune to mumps, measles and rubella, some individuals, particularly those born between 1958 and 1980, do not have optimal vaccine coverage and might not be protected.1 Adults born in 1957 or earlier are generally protected as a result of natural disease in childhood. The live viral vaccine is contraindicated in recipients of solid-organ transplants39,40,41,42 because of the risk of major complications including encephalitis. Transplant programmes might, therefore, consider checking titres before transplantation and vaccinating with 1–2 doses of vaccine if indicated, perhaps especially for those living in, or who may travel to, regions of increased disease activity (including measles in Europe and much of the developing world). Some paediatric solid-organ transplant recipients on low-dose (often single-agent) immunosuppression have been vaccinated after transplantation but this has not been shown to be safe in adult recipients and could lead to serious complications including meningoencephalitis so should be avoided. If exposure to such viral infections (especially measles) occurs and a need exists for secondary prophylaxis, γ globulin or intravenous immunoglobulin could be administered, although such situations have not been systematically studied.42

Human papilloma virus

The majority of female kidney transplant recipients are infected with human papilloma virus (HPV).24,43 These women have a 14-fold increased risk of cervical cancer, a ≤50-fold increased risk of vulvar cancer and a ≤100-fold increased risk of anal cancer.43 HPV vaccine is routinely recommended for male and female patients aged 9–26 years to prevent cancers and warts caused by certain HPV types. This vaccine is intended for use prior to viral exposure.4 No efficacy data on the use of HPV vaccine to treat pre-existing HPV disease is available and the vaccine is not recommended for this indication. The HPV vaccine is made from the outer protein coat of the virus. In a trial of 47 recipients of solid-organ transplants who were given the HPV vaccine series, a vaccine response was seen in 63.2%, 68.4%, 63.2% and 52.6% for HPV types 6, 11, 16 and 18, respectively.24 Factors that led to reduced immunogenicity included vaccination early after transplantation (P = 0.019), lung transplant (P = 0.007) and high tacrolimus levels (P = 0.048). The reduced immunogenicity of this vaccine after transplantation argues in favour of vaccination prior to solid-organ transplantation whenever possible.

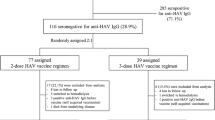

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A vaccine is recommended for renal transplant recipients who travel to endemic regions, men who have sex with men, patients with chronic liver disease and those with a history of illicit drug use (injection or non-injection).1 In 2011, hepatitis A vaccine coverage among those with chronic liver conditions in the USA was fairly low at 17%.6 A trial of hepatitis A vaccine in solid-organ transplant recipients resulted in seroconversion after the primary dose in 41% of liver transplant recipients, 24% of kidney transplant recipients, and 90% of normal controls.44 After the booster dose, the respective rates were 97%, 72%, and 100% (P <0.001). However, 2 years later, only 59% of liver transplant and 26% of kidney transplant seroconverters retained protective titres.45 Vaccination after transplantation might, therefore, not provide adequate or durable protection; for those patients on high-dose immunosuppression who are at high risk of exposure (for example, those intending to travel), the use of γ globulin in addition to vaccination can be considered.

Bacillus Calmette–Guérin

BCG is a live, attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis that is given to prevent tuberculosis (primarily in children) or treat bladder cancer. Administration in immunocompromised hosts can cause disseminated disease requiring mycobacterial therapy and should be avoided.

Occupational

Certain occupations require consideration of specific vaccinations. As rabies vaccine is not live, it is likely to be safe in transplant recipients; as immunity wanes, repeat vaccination should likely occur at more frequent intervals, perhaps based on periodic monitoring of titres. When rabies vaccine was used as postexposure prophylaxis in three transplant recipients with exposure to donor-derived rabies, immunity was safely and adequately achieved.46 No reports of anthrax vaccine safety in transplant recipients exist, but as this vaccine is also not live it is anticipated to be safe. Smallpox vaccine is a live viral vaccine and is contraindicated in immunosuppressed hosts.

Travel-related

Certain vaccines are indicated for travel to various endemic regions.47 Perhaps the vaccine of greatest concern is yellow fever, which (as a live viral vaccine) is contraindicated after solid-organ transplantation.47 When vaccination is not given, a yellow fever vaccine waiver letter stating the contraindication to vaccination is acceptable to most governments—such letters should bear the stamp of an official, approved yellow fever immunization centre. Although some immunosuppressed travelers have tolerated the vaccine, including 19 solid-organ transplant recipients living in an endemic region (Brazil),48 complications including death have been reported in immunosuppressed individuals.49 Use of the vaccine in immunocompromised travelers is, therefore, not recommended.4,42 Intravenous immunoglobulin was administered to a renal transplant recipient who was erroneously given yellow fever vaccine, with no evidence of vaccine-associated viscerotropic disease.50

Further country-specific vaccine information is available from the Centers for Disease Control Yellow Book.42 Vaccines given prior to transplantation might provide adequate protection. An analysis of 53 solid-organ transplant recipients who were vaccinated prior to transplantation (including 29 kidney recipients and 18 liver recipients) showed that 98% had protective titres of antibodies at a median of 3 years (range 0.8–21 years) after transplantation and 13 years (range 2–32 years) after vaccination, suggesting that antibodies to yellow fever persist long-term in solid-organ transplant recipients who have been vaccinated prior to transplantation.51 Family members of immunosuppressed patients can receive yellow fever vaccine.

Vaccination of close contacts

Close contacts of transplant recipients should be properly vaccinated to provide the transplant recipient with an additional layer of protection against infection (sometimes referred to as 'cocooning'). They can receive most vaccines, including zoster, yellow fever, measles, mumps and rubella and other injectable live viral vaccines.3,4,10 Certain vaccines should be avoided, however, including LAIV, smallpox (primarily for military use) and oral polio (which is no longer used in the USA but is in use elsewhere). If LAIV is the only available option, it can be given provided good use of infection-prevention precautions (that is, frequent handwashing) is maintained for a 2-week period after vaccination; viral shedding has been reported to decrease more than a week after LAIV administration.52 To date, the oral rotavirus vaccine used in small children has not been shown to result in disease in transplant recipients,4 although caution and frequent handwashing should be practiced. In general, withholding or delaying the usual childhood vaccines in the home of an immunocompromised host should be avoided, as this approach will increases the risk of true disease in the home. Annual influenza vaccination of household members and healthcare workers with the injectable influenza vaccine is strongly recommended and mandated in some hospitals.

Conclusions

Vaccination is an easy and generally safe way to enhance the care of kidney transplant recipients. Immunogenicity before transplantation tends to be higher than after transplantation, therefore, pretransplant vaccination, when possible, is the optimal approach to convey protection to this vulnerable population. After transplantation, delaying vaccines (or perhaps repeating vaccines if given early) for the first 6–12 months might result in higher rates of protection; however, seasonal influenza vaccine should be given, including within the first 1–3 months after transplantation. Although some concerns have been raised about increased HLA sensitization after vaccination, clinical data do not suggest harm. Overall, non-live vaccines seem to be immunogenic, protective and safe. Future research is needed to investigate the impact of various immunosuppressive protocols on vaccine responses; optimal timing of vaccination after transplantation; effectiveness of boosters, multiple doses and intradermal administration; extent and durability of protection; use of adjuvants; safety and adverse effects, including sensitization, and clinically meaningful end points in vaccine trials.

Review criteria

This review was compiled using a PubMed search with no date limits. Key search terms used were “transplant”, “vaccines”, “immunization” and “HLA antibody”. Primarily English language, full-text papers were used.

References

Bridges, C. B., Coyne-Beasley, T., Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), ACIP Adult Immunization Work Group & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 63, 110–112 (2014).

World Health Organization. WHO recommendations for routine immunization—summary tables. Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals [online], (2014).

Danziger-Isakov, L., Kumar, D. & AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Vaccination in solid organ transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 13 (Suppl. 4), 311–317 (2013).

Rubin, L. G. et al. 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin. Infect. Dis. 58, e44–e100 (2014).

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Transplant Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 9 (Suppl. 3), S1–S155 (2009).

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC). Noninfluenza vaccination coverage among adults—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 62, 66–72 (2013).

Struijk, G. H. et al. Meningococcal sepsis complicating eculizumab treatment despite prior vaccination. Am. J. Transplant. 13, 819–820 (2013).

Bond, T. C., Spaulding, A. C., Krisher, J. & McClellan, W. Mortality of dialysis patients according to influenza and pneumococcal vaccination status. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 60, 959–965 (2012).

Atkinson, W., Wolfe, S., & Hamborsky, J. (Eds) Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases 12th edn (Public Health Foundation, 2012).

Harpaz, R., Ortega-Sanchez, I. R. & Seward, J. F. Prevention of herpes zoster: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm. Rep. 57, 1–30 (2008).

Marin, M., Guris, D., Chaves, S. S., Schmid, S. & Seward, J. F. Prevention of varicella: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm. Rep. 56, 1–40 (2007).

Kumar, D. et al. Guidance on novel influenza A/H1N1 in solid organ transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 10, 18–25 (2010).

Kumar, D. et al. Influenza vaccination in the organ transplant recipient: review and summary recommendations. Am. J. Transplant. 11, 2020–2030 (2011).

Siegrist, C. A. et al. Responses of solid organ transplant recipients to the AS03-adjuvanted pandemic influenza vaccine. Antivir. Ther. 17, 893–903 (2012).

Katerinis, I. et al. De novo anti-HLA antibody after pandemic H1N1 and seasonal influenza immunization in kidney transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 11, 1727–1733 (2011).

Danziger-Isakov, L. et al. Effects of influenza immunization on humoral and cellular alloreactivity in humans. Transplantation 89, 838–844 (2010).

Baluch, A. et al. Randomized controlled trial of high-dose intradermal versus standard-dose intramuscular influenza vaccine in organ transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 13, 1026–1033 (2013).

Hurst, F. P., Lee, J. J., Jindal, R. M., Agodoa, L. Y. & Abbott, K. C. Outcomes associated with influenza vaccination in the first year after kidney transplantation. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 6, 1192–1197 (2011).

Eckerle, I., Rosenberger, K. D., Zwahlen, M. & Junghanss, T. Serologic vaccination response after solid organ transplantation: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 8, e56974 (2013).

Kumar, D., Welsh, B., Siegal, D., Chen, M. H. & Humar, A. Immunogenicity of pneumococcal vaccine in renal transplant recipients—three year follow-up of a randomized trial. Am. J. Transplant. 7, 633–638 (2007).

Birdwell, K. A. et al. Decreased antibody response to influenza vaccination in kidney transplant recipients: a prospective cohort study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 54, 112–121 (2009).

Blumberg, E. A. et al. The immunogenicity of influenza virus vaccine in solid organ transplant recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 22, 295–302 (1996).

Lawal, A. et al. Influenza vaccination in orthotopic liver transplant recipients: absence of post administration ALT elevation. Am. J. Transplant. 4, 1805–1809 (2004).

Kumar, D. et al. Immunogenicity of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in organ transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 13, 2411–2417 (2013).

Chon, W. J. et al. Changing attitudes toward influenza vaccination in U.S. Kidney transplant programs over the past decade. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 5, 1637–1641 (2010).

Danzinger-Isakov, L. & Kumar, D. Guidelines for vaccination of solid organ transplant candidates and recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 9 (Suppl. 4), S258–S262 (2009).

Cordero, E. et al. Therapy with m-TOR inhibitors decreases the response to the pandemic influenza A H1N1 vaccine in solid organ transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 11, 2205–2213 (2011).

John, S. et al. Prophylaxis of hepatitis B infection in solid organ transplant recipients. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 6, 309–319 (2013).

Fiorante, S., Lopez-Medrano, F., Ruiz-Contreras, J. & Aguado, J. M. Vaccination against Streptococcus pneumoniae in solid organ transplant recipients [Spanish]. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 27, 589–592 (2009).

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC). Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine for adults with immunocompromising conditions: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 61, 816–819 (2012).

Smith, K. J., Nowalk, M. P., Raymund, M. & Zimmerman, R. K. Cost-effectiveness of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in immunocompromised adults. Vaccine 31, 3950–3956 (2013).

McCashland, T. M., Preheim, L. C. & Gentry, M. J. Pneumococcal vaccine response in cirrhosis and liver transplantation. J. Infect. Dis. 181, 757–760 (2000).

Posfay-Barbe, K. M. et al. Varicella-zoster immunization in pediatric liver transplant recipients: safe and immunogenic. Am. J. Transplant. 12, 2974–2985 (2012).

Pittet, L. F. & Posfay-Barbe, K. M. Immunization in transplantation: review of the recent literature. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 18, 543–548 (2013).

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC). Updated recommendations for use of VariZIG—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 62, 574–576 (2013).

Zuckerman, R. A. & Limaye, A. P. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) in solid organ transplant patients. Am. J. Transplant. 13 (Suppl. 3), 55–66 (2013).

Oxman, M. N. et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 2271–2284 (2005).

Beil, S., Kreuzer, M. & Pape, L. Course of immunization titers after pediatric kidney transplantation and association with glomerular filtration rate and kidney function. Transplantation 94, e69–e71 (2012).

Avery, R. K. & Ljungman, P. Prophylactic measures in the solid-organ recipient before transplantation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33 (Suppl. 1), S15–S21 (2001).

Duchini, A., Goss, J. A., Karpen, S. & Pockros, P. J. Vaccinations for adult solid-organ transplant recipients: current recommendations and protocols. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 16, 357–364 (2003).

Molrine, D. C. & Hibberd, P. L. Vaccines for transplant recipients. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 15, 273–305 (2001).

Kotton, C. N. & Freedman, D. O. in CDC Health Information for International Travel 2014, Ch. 8 (ed. Brunette, G. W.) 544–555 (Oxford University Press, 2014).

Hinten, F., Meeuwis, K. A., van Rossum, M. M. & de Hullu, J. A. HPV-related (pre)malignancies of the female anogenital tract in renal transplant recipients. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 84, 161–180 (2012).

Stark, K. et al. Immunogenicity and safety of hepatitis A vaccine in liver and renal transplant recipients. J. Infect. Dis. 180, 2014–2017 (1999).

Gunther, M. et al. Rapid decline of antibodies after hepatitis A immunization in liver and renal transplant recipients. Transplantation 71, 477–479 (2001).

Vora, N. M. et al. Raccoon rabies virus variant transmission through solid organ transplantation. JAMA 310, 398–407 (2013).

Kotton, C. N. & Hibberd, P. L. Travel medicine and transplant tourism in solid organ transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 13 (Suppl. 4), 337–347 (2013).

Azevedo, L. S. et al. Yellow fever vaccination in organ transplanted patients: is it safe? A multicenter study. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 14, 237–241 (2012).

Kengsakul, K., Sathirapongsasuti, K. & Punyagupta, S. Fatal myeloencephalitis following yellow fever vaccination in a case with HIV infection. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 85, 131–134 (2002).

Slifka, M. K. et al. Antiviral immune response after live yellow fever vaccination of a kidney transplant recipient treated with IVIG. Transplantation 95, e59–e61 (2013).

Wyplosz, B. et al. Persistence of yellow fever vaccine-induced antibodies after solid organ transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 13, 2458–2461 (2013).

Ali, T. et al. Detection of influenza antigen with rapid antibody-based tests after intranasal influenza vaccination (FluMist). Clin. Infect. Dis. 38, 760–762 (2004).

Chi, C. et al. Guidelines for vaccinating dialysis patients and patients with chronic kidney disease. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention [online] (2012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing financial interests.

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kotton, C. Immunization after kidney transplantation—what is necessary and what is safe?. Nat Rev Nephrol 10, 555–562 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2014.122

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2014.122

This article is cited by

-

Vaccination in patients with kidney failure: lessons from COVID-19

Nature Reviews Nephrology (2022)

-

Pre-transplant donor HBV DNA+ and male recipient are independent risk factors for treatment failure in HBsAg+ donors to HBsAg- kidney transplant recipients

BMC Infectious Diseases (2021)

-

Live Virus Vaccines in Transplantation: Friend or Foe?

Current Infectious Disease Reports (2015)