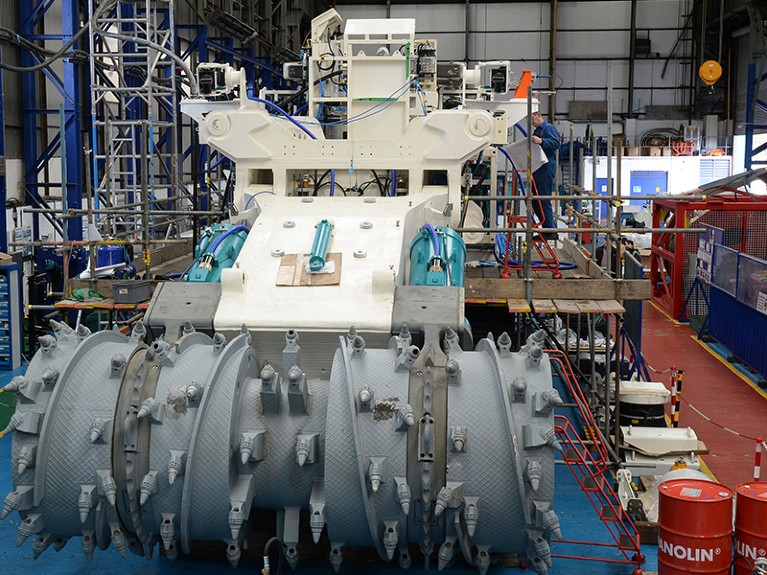

Giant excavators for use in deep-sea mining must stay parked for now.Credit: Nigel Roddis/Reuters

For more than a week, representatives of nations around the world have been meeting at a session of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) in Kingston, Jamaica. The ISA was established under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea 30 years ago with the task of protecting the sea bed in international waters — which comprise roughly half of the world’s ocean. The goal of the latest meeting is to write the rules for the commercial mining of metals such as cobalt, manganese and nickel. These are needed in increasing quantities, mainly to power low-carbon technologies, such as battery storage.

The meeting is set to end on 29 March, and there’s mounting concern among researchers that the final text is being rushed, not least because some countries including China, India, Japan and South Korea want to press ahead with commercial exploitation of deep-sea minerals. Some in the mining industry would like excavations to begin next year.

China dominates the global supply of critical minerals and so far has the most sea-bed exploration licences of any country. These permits do not allow commercial exploitation. One company, meanwhile, The Metals Company, based in Vancouver, Canada, wants to apply for a commercial permit, potentially in late July.

Hypocrisy is threatening the future of the world’s oceans

There is little justification for such haste. Commercial sea-bed mining is not permitted for a reason: too little is known about the deep-sea ecosystem, such as its biodiversity, and its interactions with other ecosystems, and the impact of disturbance from commercial operations. Until we have the results of long-term studies, the giant robotic underwater excavators, drills and pumps that are ready to go must remain parked. Researchers have told Nature that the text is nowhere near ready, and that important due diligence is being circumvented. Outstanding issues need to be resolved, such as what is considered an acceptable level of environmental harm and how much contractors should pay the ISA for the right to extract minerals.

Last month, the ISA published the latest draft of its mining regulations text. This ran to 225 pages, and researchers and conservation groups were alarmed to see that, unlike previous drafts, it incorporated proposals that would speed up the process for issuing commercial permits, and it also weakened environmental protections.

Worryingly, a few of the changes in the latest text were not identified by square brackets — the practice in international negotiations to highlight wording that has not been agreed on by all parties. Nor were the sources for some changes attributed.

Furthermore, in an earlier version of the text, there was a proposal to include measures to protect rare or fragile ecosystems, but this wording is not in the latest draft. Another suggestion was to require that mining applications be decided on within 30 days of their receipt, rather than waiting for the ISA’s twice-yearly meeting — an idea that has support from some in the industry and that does appear in the latest draft.

Proposing changes to draft texts is normal in a negotiation, but failing to publicly identify who is proposing them is not. It is damaging to trust and a risk to reaching an outcome in which all parties are happy.

Questions are rightly being asked of the leadership of the ISA secretariat, which organizes meetings and is responsible for producing and distributing texts, as well as the leadership of the ISA’s governing council. Nature has reached out to the secretariat with questions, but no response was received by the time this editorial went to press. We urge the ISA to respond, engage and explain.

Norway’s approval of sea-bed mining undermines efforts to protect the ocean

It is possible that the benefits to low-carbon technologies outweigh the risks of deep-sea mining if these are mitigated. But some 25 countries are calling for a moratorium on the practice, at least until the science is better understood. The European Parliament also backs a moratorium. This is also the official view of the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy, a group of 18 countries that pledged to not undertake commercial deep-sea mining in their national waters — despite founding member Norway’s decision to open up applications for commercial licences, which the European Parliament has criticized.

The UN Convention on Migratory Species is urging that its member states should neither encourage nor engage in deep-sea mining “until sufficient and robust scientific information has been obtained to ensure that deep-seabed mineral exploitation activities do not cause harmful effects to migratory species, their prey and their ecosystems”.

The ISA and its member states should exercise care, make their decisions on a consensus of evidence and be transparent in doing so, because transparency is foundational to the success of international relations. The deep seas are the least explored parts of the planet; we should not allow for their loss before we even understand their complexities.

Norway’s approval of sea-bed mining undermines efforts to protect the ocean

Norway’s approval of sea-bed mining undermines efforts to protect the ocean

Hypocrisy is threatening the future of the world’s oceans

Hypocrisy is threatening the future of the world’s oceans

The global fight for critical minerals is costly and damaging

The global fight for critical minerals is costly and damaging