When Ebola reached Kampala, the capital of Uganda, in September, I was reminded of a spine-chilling phone call I received in August 2014. “Leave everything and come down: Ebola has entered West Point.” West Point is a poor, densely populated peninsula, home to 70,000 people, in Liberia’s capital, Monrovia. From there, we feared the disease could explode across the country.

How did we eventually get to zero Ebola cases in Liberia? By using some unconventional approaches. We supplied illicit drugs to gang members and food to armed robbers so that we could trace their contacts in West Point. Above all, we learnt that mobilizing communities to help themselves is crucial to containing Ebola.

I was head of case detection in Liberia during that crisis. Now, from Ethiopia, I manage the COVID-19 programme of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and provide guidance to our Ebola response team in Uganda.

Can mRNA vaccines transform the fight against Ebola?

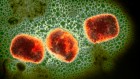

So far, at least 53 people in Uganda have died of the Sudan species of Ebola virus. Unlike the Zaire species in the West Africa crisis, the Sudan virus has no approved vaccines or therapeutics. Several weeks ago, cases were found among schoolchildren in Kampala. Yet Ebola response workers meet with denial and resistance, indicating that a fundamental lack of trust is holding back the response.

We also faced these issues in Liberia. We found that contact tracing alone was not enough. To succeed, we had to deputize members of the public — 5,700 of them at the peak of the crisis. We called them active case finders.

They went house-to-house, tracking sick people and all of their contacts across 1.6 million households. People needed to trust the messenger to believe the message. They would trust a neighbour more than a stranger clad in head-to-foot personal protective equipment (PPE).

Case finders were recruited by local chiefs, community leaders and religious leaders, who received stipends from the Ebola response team, funded by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Development Programme. Each case finder received a monthly stipend to monitor 20–25 houses. Every day, they would visit these houses to find and report infections, contacts and unreported deaths. They visited people with Ebola at home to provide social and psychological support.

When there was a confirmed case or high-risk contact, chiefs would ensure that local youths left rice and water for the household so that the members could voluntarily self-quarantine. To reduce stigma, local leaders hosted a community ceremony to welcome back anyone who had completed quarantine, with a reintegration package of food, cash and clothing.

Ebola outbreak in Uganda: how worried are researchers?

Secret burials are a major driver of Ebola spread, so cultural sensitivity was also key. The virus is at its peak in corpses. It can spread through someone touching just a drop of blood or saliva or clothes that have been in contact with bodily fluids. To protect the living, the bodies of those who have died of Ebola must be handled by workers in full PPE, and there must be a thorough case investigation that includes immediate contact tracing. This is worlds away from the traditional practice of washing the bodies of loved ones by hand.

It is not easy to give up practices that help people to grieve. In Liberia, where 12% of people are Muslim, we hired imams to lead the Ebola response among their followers and one to lead the Muslim burial team in the Caldwell neighbourhood of Monrovia. Religious leaders absolved followers from washing the deceased by hand and permitted praying while keeping 2 metres away from the body.

The rise in deaths in Ebola treatment units in Uganda has scared some people into seeking care from religious and traditional healers. One man who had contact with Ebola escaped lockdown in the Kassanda district and then died in Kampala after infecting 13 people, including his 6 children, who attend 3 different schools.

In Liberia, we found that the earlier we could get people to a treatment centre, the better their odds of survival, because they would receive hydration, food and medication. So we made every effort to identify people with Ebola at the onset of symptoms. Contact tracers were embedded at Ebola hotspots 24 hours a day to monitor people’s temperatures. As survival rates increased, more people were encouraged to come to treatment units. In one of our last Ebola resurgences, in 2016, we had a 100% survival rate in one treatment unit other than the index case (that person had died on her arrival from Guinea).

Liberia spent millions of dollars on these measures. The global community — the UN, World Bank and private philanthropists such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation — need to fund a similar effort in Uganda. The Africa CDC is ideally placed to coordinate it. Through a partnership with the Mastercard Foundation in Toronto, Canada, we have established systems of distribution for health-care resources such as COVID-19 vaccines, in 50 countries. We have a history of investing in the community-health workforce. And we have a mandate from the African Union.

I never again want to see what I saw when I arrived in West Point that day eight years ago. Two people were crawling on their knees and vomiting blood; three of their contacts were at large. To avert another such epidemic, let’s recruit thousands to be case finders in Uganda.

Can mRNA vaccines transform the fight against Ebola?

Can mRNA vaccines transform the fight against Ebola?

Ebola outbreak in Uganda: how worried are researchers?

Ebola outbreak in Uganda: how worried are researchers?

Where are the Ebola diagnostics from last time?

Where are the Ebola diagnostics from last time?

Exclusive: Behind the front lines of the Ebola wars

Exclusive: Behind the front lines of the Ebola wars