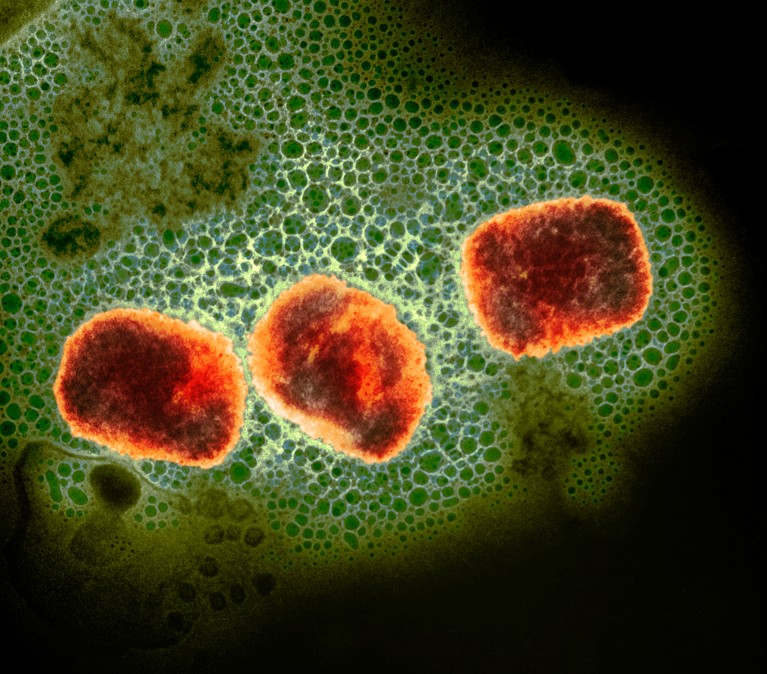

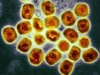

Monkeypox virus particles (artificially coloured).Credit: UK Health Security Agency/Science Photo Library

A virulent strain of the monkeypox virus has gained the ability to spread through sexual contact, new data suggest. This has alarmed researchers, who fear a reprise of the worldwide mpox outbreak in 2022.

Evidence from past outbreaks indicates that this strain, called clade I, is more lethal than the separate strain that sparked the 2022 outbreak. Clade I has for decades caused small outbreaks, often limited to a few households or communities, in Central Africa. Sexually acquired clade I infections had not been reported before last year.

But starting in late 2023, a clade I strain that seems to spread through sexual contact has caused a cluster of infections in a conflict-ridden region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in Central Africa. A preprint1 posted on 15 April reports that 241 suspected and 108 confirmed infections are connected to this outbreak — and testing capacity is limited, so there are probably many more cases. Almost 30% of the confirmed infections were in sex workers.

Adding to the challenges, the region is facing a humanitarian crisis, and the DRC is contending with the aggressive spread of other diseases, such as cholera. The combination means there is a “substantial risk of outbreak escalation beyond the current area”, says Anne Rimoin, an epidemiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, who has worked on mpox outbreaks in the DRC since 2002.

Unheeded warnings

The monkeypox virus can cause painful, fluid-filled lesions on the skin and, in severe cases, death. (Although the disease was renamed mpox in 2022, the virus is still called monkeypox virus.) The virus persists in wild animals in several African countries, including the DRC, and occasionally spills into people.

The first large reported outbreak with human-to-human transmission occurred in 2017 in Nigeria and was caused by a strain called clade II, which is less virulent than clade I. The outbreak caused more than 200 confirmed and 500 suspected cases. At the time, researchers cautioned that the clade II strain might have adapted to spread through sexual contact.

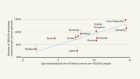

Their warnings were not heeded; in 2022, a global outbreak driven in part by sexual contact prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare it a public-health emergency. The outbreak, which is still ongoing, is caused by a clade II strain and has infected more than 95,000 people and killed more than 180.

Monkeypox in Africa: the science the world ignored

Although mpox infections have waned globally since 2022, they have been trending upwards in the DRC: last year, the country reported more than 14,600 suspected infections and more than 650 deaths. In September, a new cluster of suspected clade I infections arose in the DRC’s South Kivu province. This cluster especially concerns researchers because many infections were in sex workers, suggesting that the virus has adapted to transmit readily through sexual contact.

This could lead to faster human-to-human spread, potentially with few symptoms, says Nicaise Ndembi, a virologist at the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, who is based in Addis Ababa. “The DRC is surrounded by nine other countries — we’re playing with fire here,” he says.

Health officials are so concerned that representatives of the DRC and 11 nearby countries met earlier this month to plan a response and to commit to stepping up virus surveillance. Only about 10% of the DRC’s suspected mpox cases last year were tested, owing to limited testing capacity. Health officials “don’t have a full picture of what’s going on”, Ndembi says.

Genetic analyses of the virus responsible for the outbreak uncovered mutations such as the absence of a large chunk of the virus’s genome, which researchers have shown is a sign of adaptation2. This has led the study’s authors to give a new name to the strain circulating in the province: clade Ib.

Making matters more fraught, South Kivu borders Rwanda and Burundi and is grappling with “conflict, displacement, food insecurity and challenges in providing adequate humanitarian assistance”, which “might represent fertile ground for further spread of mpox”, the WHO warned last year.

Vaccines and treatment needed

In 2022, many wealthy countries offered vaccines against smallpox, which also protect against mpox, to individuals at high risk of contracting the disease. But few vaccine doses have reached African countries, where the disease’s toll has historically been highest.

While the DRC weighs regulatory approval for these vaccines, the United States has committed to providing the DRC with enough doses to inoculate 25,000 people, and Japan has said it will also provide vaccines, says Rosamund Lewis, technical lead for mpox at the WHO. But a vaccination drive in the DRC would require hundreds of thousands — if not millions — of doses to inoculate every individual at high risk of infection, she says.

It’s not clear how much protection these vaccines will provide against clade I mpox, but Andrea McCollum, a poxvirus epidemiologist at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, says that data from animal studies are promising. Researchers are also conducting a trial in the DRC of tecovirimat, an antiviral that is thought to be effective against the monkeypox virus. Results are expected in the next year, McCollum says.

The WHO and the CDC have helped to procure equipment that will allow for more rapid diagnosis of the disease in the DRC, especially in rural areas, Lewis says. She adds that the rapid mobilization of African health officials gives her hope that the outbreak can be controlled before the clade Ib strain starts spreading elsewhere.

WHO may soon end mpox emergency — but outbreaks rage in Africa

WHO may soon end mpox emergency — but outbreaks rage in Africa

‘The disease will be neglected’: scientists react to the WHO ending mpox emergency

‘The disease will be neglected’: scientists react to the WHO ending mpox emergency

What does the future look like for monkeypox?

What does the future look like for monkeypox?

The monkeypox virus is mutating. Are scientists worried?

The monkeypox virus is mutating. Are scientists worried?