Abstract

Study design:

Prospective cohort study.

Objectives:

Dysphagia is a relatively common secondary complication in patients with traumatic cervical spinal cord injuries (TCSCI). The purpose of this study was to determine the incidence of aspiration and penetration in patients with acute TCSCI.

Setting:

Tampere University Hospital, Tampere, Finland.

Methods:

A total of 46 patients with TCSCI were evaluated with a videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS). Rosenbek’s penetration-aspiration scale (PAS) was used to classify the degree of penetration or aspiration. The medical records of each patient were systematically reviewed.

Results:

Of the 46 patients, 85% were male. The mean age at the time of the injury was 62.1 years. Most patients had an incomplete injury (78%), and most of them due to a fall (78%). In the VFSS 19 (41%) patients penetrated and 15 (33%) aspirated. Only 12 (26%) of the patients had a PAS score of 1 indicating that swallowed material did not enter the airway. Of the patients who aspirated, 73% had silent aspiration.

Conclusion:

The incidence of penetration or aspiration according to VFSS is high in this cohort of patients with TCSCI. Therefore, the swallowing function of patients with acute TCSCI should be routinely evaluated before initiating oral feeding. VFSS is highly recommended, particularly to rule out the possibility of silent aspiration and to achieve information on safe nutrition consistency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) leads to abrupt changes in motor, sensory, and autonomic functions below the level of injury, causing many secondary conditions and increasing the risk for various complications. Especially among cervically injured SCI patients, dysphagia is a relatively common complication.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Dysphagia is associated with many negative short- and long-term outcomes, such as pneumonia and other respiratory complications as well as malnutrition, dehydration, and reduced quality of life.12, 13, 14, 15 In addition, while SCI in general causes a substantial economic burden, the treatment of respiratory complications further raises hospital costs.16

By definition, dysphagia is described as a difficulty in the regular passage of swallowed bolus from the mouth to the stomach.17 Penetration and aspiration are the most severe subtypes of dysphagia. Penetration means that swallowed material enters the airways, but remains above the vocal folds.18 In the case of aspiration, the swallowed material passes below the vocal cords.18 Aspiration can occur with a cough reflex or silently. The videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS) is considered to be the gold standard method for objectively evaluating the degree of dysphagia. Rosenbek’s penetration-aspiration scale (PAS) is a widely used method to classify the severity of penetration and aspiration seen on VFSS.18

A recent study revealed that the incidence of traumatic SCI in Finland is 31.8 per million and that the vast majority of these injuries are cervical resulting in tetraplegia (70% of all SCIs).19 On the basis of the literature the incidence of dysphagia in cervical SCI patients varies from 16 to 80%.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 A summary of the previous studies on cervical SCI and dysphagia is presented in Table 1.

The aim of this study was to determine the incidence of laryngeal penetration/aspiration in patients with acute TCSCI by using VFSS and Rosenbek’s PAS.

Materials and methods

Study frame and ethics

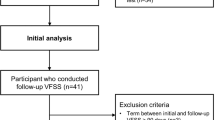

This prospective study was conducted at Tampere University Hospital, Tampere, Finland. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Pirkanmaa Hospital District, Tampere, Finland (R12250). Written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki was obtained from all the subjects prior to commencing the research. We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research. In Finland, acute care, subacute rehabilitation, and the lifelong follow-up of patients with TSCI is centralized at three university hospitals, which are situated in Helsinki, Oulu, and Tampere. Tampere University Hospital serves a population of 2.8 million from both urban and rural areas. All applicable patients (n=94) with TCSCI admitted to Tampere University Hospital from February 2013 to April 2015 were asked to participate in this study. We included all patients with TCSCI regardless of the severity or cervical level of injury. Possible confounding factors were controlled with numerous exclusion criteria. The medical records of each patient were reviewed to verify the history of neurological diseases and head, neck or cervical spine surgeries. A flowchart displaying the study process (incl. exclusion criteria) is presented in Figure 1.

Spinal cord injury characteristics

The following variables were recorded for all patients: gender; age at the time of injury; injury mechanism (as per the International SCI Core Data Set;20) method of treatment (anterior surgery, posterior surgery, multiple surgeries, no surgery); presence of nasogastric tube, tracheostomy, and/or hard collar at the time of VFSS. The International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury was used to evaluate and classify the neurological consequences of the spinal cord injury.21, 22 The completeness of the injury was defined according to the American Spinal Injury Association impairment scale (AIS): AIS A=motor-sensory complete, AIS B=motor complete-sensory incomplete, or AIS C–D=motor-sensory incomplete.

Videofluoroscopic swallowing study and penetration-aspiration scaling

All 46 patients were first assessed for clinical indicators of penetration or aspiration (that is, coughing, throat clearing, choking and changes in voice quality) by a speech and language therapist (TI). To confirm the incidence of penetration/aspiration, the patients were subjected to VFSS (Siemens Axiom Luminos DRF, Erlangen, Germany). The frame rate was 15 frames per second. The VFSS was conducted by a speech and language therapist (TI) and a radiologist. The VFSS was carried out with the patient in an upright position from a lateral scanning view. The VFSS protocol included 5 ml, 10 ml and 20 ml boluses of a thin, water-soluble contrast agent (Omnipaque 350 mgI ml−1, GE Healthcare, Oslo, Norway). The patients were asked to hold the bolus in their mouth until they were instructed to swallow. In addition, they were guided to swallow as many times as they needed and to cough and clear their throat if needed. After the primary swallow, the fluoroscopy was continued for at least 6 s to clarify if penetration/aspiration occurred after the initial swallow. In patients with a tracheostomy (n=6), the examination was conducted with a decuffed cannula. The VFSS was discontinued if severe aspiration occurred. The Rosenbek’s PAS scoring was conducted together by a speech therapist (TI) and a radiologist (IR-K). The timing of penetration or aspiration was classified as(1) pre-,(2) during-, or(3) post swallowing.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences software program (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0, Armonk, NY, USA) was used to perform all the statistical analyses.

Results

Patients

In total, 46 out of 94 patients with TCSCI were included in this prospective study. The characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 2. Of the 48 excluded patients, 36 (75%) were male and 12 (25%) were female. Mean age was 63.6 years (median 66.1, min.–max. 17.6–94.4).

VFSS

In total, 121 swallows were analysed using VFSS. The mean time from injury to the VFSS was 19.1 days (s.d.=17.5, median=13.5, min=2, max=87). The highest PAS score from each patient was included in the statistical analyses. Fifteen (33%) patients had aspiration and 19 (41%) patients had penetration on the VFSS. Twelve (26%) patients had a swallowing score of 1, indicating that swallowed material did not enter the airway. The Rosenbek’s Penetration-Aspiration Scale scores are presented in Table 3. The penetration or aspiration occurred during swallowing in 17 (37%) patients, post-swallowing in 9 (20%) patients, and during and post-swallowing in 7 (15%) patients. Pre-swallowing penetration or aspiration was not detected. In one case (2%) the timing of the silent aspiration was missed because there was a delay in starting the fluoroscopy. Six patients (13%) had severe aspiration and required a percutaneous feeding tube.

Discussion

The main finding of our study was that the incidence of penetration/aspiration based on original PAS scoring was high (74%) in this cohort of patients with TCSCI. Even if we consider PAS scores 1–2 representing normal variation in swallowing23, 24, 25 the incidence of unsafe swallowing is still considerably high (48%). Methodological heterogeneity among earlier studies makes it difficult to compare our results to prior findings. In the earlier studies, the incidence of aspiration varies between 6% and 41%,2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and in some studies, the incidence of aspiration was not reported precisely.1, 2, 5 The incidence of penetration was reported in only two studies, and it varied from 5 to 24%.3, 6 Wolf and Meiners2 reported the incidence of severe aspiration to be 41%, but they included only CSCI patients with respiratory insufficiency. Seidl et al.6 reported the overall incidence of aspiration to be 11% and they included all patients whose complete data was available. The higher incidence of aspiration in the study of Wolf and Meiners might be explained with the study population of more severely injured patients. Shin et al.7 performed VFSS to all patients included in their study, but they reported that the mean duration between the onset of spinal cord injury and VFSS was 178.35 days (range 12–1062 days). They concluded that a broad time frame lead to limitations when interpreting the results of VFSS, as dysphagia in CSCI patients tends to be transient and the low prevalence of aspiration may be explained by recovery.

To the best of our knowledge this is the first study conducted on patients with TCSCI that has used the Rosenbek’s PAS and a precisely described VFSS protocol in the data collection. The age, gender and injury mechanism distributions of our study sample are comparable with the ones published by Koskinen et al.19 Our study sample can be considered to be unbiased and representative of Finnish patients with TCSCI as it includes a consecutive series of admitted patients with SCI. We also presented the exact time frame between the injury and VFSS. As shown in Table 1, the time frame between the injury and the instrumental swallowing study is poorly reported in prior studies. In the majority of prior studies, the instrumental—that is, VFSS or fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing—evaluation was performed only when dysphagia was clinically suspected.1, 3, 4, 5 Therefore, all patients who may have been silent aspirators were perhaps not identified. Patients with CSCI have often reduced ability to cough. Weakness in coughing complicates clinical swallowing evaluation and therefore this patient group may have a higher risk for silent aspiration. In our study of the patients who aspirated, 73% had silent aspiration. In two retrospective studies with a large heterogeneous group of dysphagic patients (n=1,101, n=2,000), the incidence of silent aspiration among patients with aspiration varied from 55 to 59%.26, 27 Clinically, a lack of awareness of silent aspiration may lead to a longer period of aspirating food or liquids into the lungs, thereby potentially elevating the risk for pneumonia or pulmonary complications. Besides, coughing is not only a clinical indicator of aspiration, but also a protective reflex against aspiration. In our study, none of the patients who aspirated were able to eject the aspirated material out of the trachea.

Further, preferably multicenter, research is recommended to determine the length and nature of dysphagia symptoms and to elaborate a management plan for TCSCI patients with dysphagia. Earlier studies have presented some risk factors, that is, age,1, 7, 8 tracheostomy,1, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10 the completeness of the injury,1, 4 and cervical surgery.1 Due to the differences in the definition of dysphagia and data collection, future research is nevertheless needed to identify risk factors for dysphagia, including penetration and aspiration.

Limitations of the study

The limitations of this study are the small sample size and the fact that the VFSS protocol included only measured boluses (5 ml, 10 ml and 20 ml) of a thin, liquid consistency. Considering the overall incidence of TCSCI in Finland, the number of recruited patients can still be seen as better than satisfactory.

The VFSS protocol used in this study was limited to measured boluses of contrast agent (of a thin, liquid consistency) in order to reduce the amount of radiation exposure to patients who did not penetrate or aspirate. We could have detected even more penetration/aspiration had we included a serial drinking task of involving thin liquid and other consistencies in our VFSS research protocol.

We decided to use rigorous exclusion criteria to reduce or eliminate confounding or ethically questionable variables. It can be argued that the incidence of penetration/aspiration would have been higher if the excluded cases were included in the study. In this study, we also focused only on VFSS findings of penetration/aspiration, although dysphagia is a much broader phenomenon.

Finally, our aim in this prospective study was to conduct the clinical examination and the VFSS as soon as possible post-injury. We did not want to set a too strict time limit since we were aware that especially conducting the VFSS for this patient group is challenging. We accepted the patients to participate in this study if they were admitted to our hospital ⩽3 months post-injury as did Wolf and Meiners.2

Conclusions

The incidence of penetration/aspiration based on original PAS scoring was high (74%) in this cohort of patients with TCSCI. Of the patients who aspirated, 73% aspirated silently (PAS 8). Therefore, swallowing should be evaluated routinely by an experienced speech therapist before initiating oral feeding. VFSS is highly recommended, particularly to rule out the possibility of silent aspiration and to achieve information on safe nutrition consistency.

Data archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Kirshblum S, Johnston MV, Brown J, O'Connor KC, Jarosz P . Predictors of dysphagia after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 1101–1105.

Wolf C, Meiners TH . Dysphagia in patients with acute cervical spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2003; 41: 347–353.

Brady S, Miserendino R, Statkus R, Springer T, Hakel M, Stambolis V . Predictors to dysphagia and recovery after cervical spinal cord injury during acute rehabilitation. J Appl Res 2004; 4: 1–11.

Abel R, Ruf S, Spahn B . Cervical spinal cord injury and deglutition disorders. Dysphagia 2004; 19: 87–94.

Shem K, Castillo K, Naran B . Factors associated with dysphagia in individuals with high tetraplegia. Top Spinal Cord Injury Rehabil 2005; 10: 8–18.

Seidl RO, Nusser-Muller-Busch R, Kurzweil M, Niedeggen A . Dysphagia in acute tetraplegics: a retrospective study. Spinal Cord 2010; 48: 197–201.

Shin JC, Yoo JH, Lee YS, Goo HR, Kim DH . Dysphagia in cervical spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 1008–1013.

Shem K, Castillo K, Wong S, Chang J . Dysphagia in individuals with tetraplegia: incidence and risk factors. J Spinal Cord Med 2011; 34: 85–92.

Shem K, Castillo K, Wong SL, Chang J, Kolakowsky-Hayner S . Dysphagia and Respiratory Care in Individuals with Tetraplegia: Incidence, Associated Factors, and Preventable Complications. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2012; 18: 15–22.

Chaw E, Shem K, Castillo K, Wong SL, Chang J . Dysphagia and associated respiratory considerations in cervical spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2012; 18: 291–299.

Shem KL, Castillo K, Wong SL, Chang J, Kao MC, Kolakowsky-Hayner SA . Diagnostic accuracy of bedside swallow evaluation versus videofluoroscopy to assess dysphagia in individuals with tetraplegia. Pm R 2012; 4: 283–289.

Smithard DG, O'Neil PA, Park C, Morris J, Wyatt R, England R et al. Complications and outcome after acute stroke: does dysphagia matter?[Article]. Stroke 1996; 27: 1200–1204.

Carrión S, Cabré M, Monteis R, Roca M, Palomera E, Serra-Prat M et al. Oropharyngeal dysphagia is a prevalent risk factor for malnutrition in a cohort of older patients admitted with an acute disease to a general hospital. Clin Nutr 2015; 34: 436–442.

Garcia-Peris P, Paron L, Velasco C, de la Cuerda C, Camblor M, Breton I et al. Long-term prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients: Impact on quality of life. Clin Nutr 2007; 26: 710–717.

Leibovitz A, Baumoehl Y, Lubart E, Yaina A, Platinovitz N, Segal R . Dehydration among long-term care elderly patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia. Gerontology 2007; 53: 179–183.

Winslow C, Bode RK, Felton D, Chen D, Meyer PR Jr . Impact of respiratory complications on length of stay and hospital costs in acute cervical spine injury. Chest 2002; 121: 1548–1554.

Logemann JA . Introduction: Definitions and basic principles of evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders. Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders 2nd ed. Austin, TX, USA: Pro-Ed. 1998 p 1–5.

Rosenbek JC, Robbins JA, Roecker EB, Coyle JL, Wood JL . A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia 1996; 11: 93–98.

Koskinen EA, Alen M, Vaarala EM, Rellman J, Kallinen M, Vainionpaa A . Centralized spinal cord injury care in Finland: unveiling the hidden incidence of traumatic injuries. Spinal Cord 2014; 52: 779–784.

DeVivo M, Biering-Sorensen F, Charlifue S, Noonan V, Post M, Stripling T et al. International Spinal Cord Injury Core Data Set. Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 535–540.

Kirshblum SC, Burns SP, Biering-Sorensen F, Donovan W, Graves DE, Jha A et al. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (revised 2011). J Spinal Cord Med 2011; 34: 535–546.

Kirshblum SC, Waring W, Biering-Sorensen F, Burns SP, Johansen M, Schmidt-Read M et al. Reference for the 2011 revision of the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2011; 34: 547–554.

Robbins J, Coyle J, Rosenbek J, Roecker E, Wood J . Differentiation of normal and abnormal airway protection during swallowing using the penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia 1999; 14: 228–232.

Daggett A, Logemann J, Rademaker A, Pauloski B . Laryngeal penetration during deglutition in normal subjects of various ages. Dysphagia 2006; 21: 270–274.

Allen JE, White CJCCC, Leonard RJ, Belafsky PC . Prevalence of penetration and aspiration on videofluoroscopy in normal individuals without dysphagia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010; 142: 208–213.

Smith CH, Logemann JA, Colangelo LA, Rademaker AW, Pauloski BR . Incidence and patient characteristics associated with silent aspiration in the acute care setting. Dysphagia 1999; 14: 1–7.

Garon BR, Sierzant T, Ormiston C . Silent aspiration: results of 2,000 video fluoroscopic evaluations. J Neurosci Nurs 2009 quiz 186-7; Aug 41: 178–185.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients, biostatistician Mika Helminen, research assistant Anne Simi, and the physiotherapists at the ICU unit, the neurosurgical ward, and the neurological rehabilitation ward of Tampere University Hospital for their assistance. This work was supported by funds from the Maire Taponen Foundation (TI).

Author contributions

TI contributed to the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and article preparation. IR-K contributed to the data collection and article preparation. TML contributed to the data interpretation and article preparation. EK contributed to the data collection and article preparation. A-MK-H contributed to the article preparation. AR contributed to the study design and article preparation

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ihalainen, T., Rinta-Kiikka, I., Luoto, T. et al. Traumatic cervical spinal cord injury: a prospective clinical study of laryngeal penetration and aspiration. Spinal Cord 55, 979–984 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.71

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.71

This article is cited by

-

Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Acute Cervical Spinal Cord Injury: A Literature Review

Dysphagia (2023)

-

Videofluoroscopic Profiles of Swallowing and Airway Protection Post-traumatic Cervical Spinal Cord Injury

Dysphagia (2022)

-

The time course of dysphagia following traumatic cervical spinal cord injury: a prospective cohort study

Spinal Cord (2020)

-

Oropharyngeal dysphagia management in cervical spinal cord injury patients: an exploratory survey of variations to care across specialised and non-specialised units

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2019)

-

Traumatic cervical spinal cord injury: recovery of penetration/aspiration and functional feeding outcome

Spinal Cord (2018)