Abstract

Suppression of target of rapamycin complex 1 (TORC1) by rapamycin ameliorates aging in diverse species. S6 kinase (S6K) is an essential mediator, but the mechanisms involved are unclear. Here we show that activation of S6K specifically in Drosophila fat-body blocked extension of lifespan by rapamycin, induced accumulation of multilamellar lysosomes and blocked age-associated hyperactivation of the NF-κB-like immune deficiency (IMD) pathway, indicative of reduced inflammaging. Syntaxin 13 mediated the effects of TORC1–S6K signaling on lysosome morphology and inflammaging, suggesting they may be linked. Inflammaging depended on the IMD receptor regulatory isoform PGRP-LC, and repression of the IMD pathway from midlife extended lifespan. Age-related inflammaging was higher in females than in males and was not lowered in males by rapamycin treatment or lowered S6K. Rapamycin treatment also elevated Syntaxin 12/13 levels in mouse liver and prevented age-related increase in noncanonical NF-κB signaling, suggesting that the effect of TORC1 on inflammaging is conserved from flies to mammals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) network senses nutrients and various stressors and plays a key role in the regulation of growth, metabolism and longevity. mTOR is a serine/threonine protein kinase that is a crucial component of mTOR complex 1 (TORC1)1. Suppression of TORC1 signaling genetically or pharmacologically by the US Food and Drug Administration-licensed drug rapamycin (Rapa), promotes lifespan and healthspan in various model organisms including nematode worms, fruit flies and mice2,3,4,5,6,7,8.

Rapa increases lifespan in Drosophila via two evolutionarily conserved TORC1 downstream effector mechanisms: increased autophagy and reduced ribosomal S6 kinase (S6K) activity3. Autophagy is a lysosome-dependent cellular clearance pathway that promotes cellular and tissue homeostasis9. Promoting autophagy enhances longevity and suppresses age-related tissue deterioration in Drosophila and mice9,10,11,12. The intestine is a crucial organ mediating the effects of increased autophagy on health during aging11,12,13,14. S6K is an AGC family kinase that regulates fundamental cellular processes including translation, lipid metabolism and immunity15. Female but not male mice carrying a S6K1 null allele are long-lived indicating a sex-specific effect of S6K on lifespan regulation16. However, the mechanisms by which reduced S6K signaling promotes lifespan and healthspan remain elusive. Drosophila provides an ideal model organism to address this question, as it has only a single S6K, with considerable homology to the mammalian p70-S6K1 (ref. 17).

Rapa treatment also ameliorates aging-associated decline in immune function18,19. A chronic inflammation, termed ‘inflammaging’ and deterioration of immune function, termed ‘immunosenescence’20,21, both occur during aging. These contribute to a wide range of age-associated diseases, such as cancer, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases21,22,23. The nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) pathway plays a key role in innate immunity, and Rapa treatment ameliorates senescence-associated NF-κB activation24. The effects of Rapa on inflammaging and lifespan are diminished in mice with genetically enhanced NF-κB activity (nfκb1−/−)25, suggesting that the late-life health-promoting effects of Rapa are mediated at least in part by limiting NF-κB signaling. Brief, late-life TORC1 inhibition can increase immune response of older people to influenza vaccination, without significant adverse effects19. Interestingly, TORC1 pathway activity shows a significant association with the load of bacteria in old flies26,27, suggesting that enhanced immune function from suppression of TORC1 may be conserved. However, the underlying molecular and cellular mechanisms of these TORC1-related effects are unclear.

In this Article, we identified the Drosophila fat body as an essential organ for suppression of S6K to extend lifespan. TORC1 inhibition by Rapa treatment repressed enlarged, multilamellar lysosomes in the Drosophila fat body, and this effect was blocked by elevating S6K activity. We identified Syntaxin 13 (Syx13), a SNARE family protein that mediates endomembrane function, as a downstream mediator of TORC1–S6K signaling. Repressing Syx13 in the fat body by double-stranded RNA interference (RNAi) induced the enlarged multilamellar lysosomes, while overexpressing Syx13 suppressed them. Further, suppression of TORC1–S6K–Syx13 signaling reduced age-associated chronic inflammation, the decline in ability to clear bacteria and extended lifespan via the endolysosomal control of regulatory PGRP-LC isoform. Moreover, repression of inflammation in mid-adulthood, by knocking down the Drosophila NF-κB like transcription factor Relish in the fat body, enhanced bacterial clearance and increased fly lifespan. Additionally, we found a notable sexual dimorphism in the fat body inflammaging and its response to reduced TORC1–S6K activity, which may contribute to the observed distinct lifespan effects of S6K in males and females. In mice, Rapa treatment increased expression of Syntaxin 12/13 (Stx12) in liver. Comparing the hepatic proteome and transcriptome of Rapa-treated mice with the transcriptome of S6K1-deficient mice showed alleviated immune processes in the aged liver as common health outcome of TORC1–S6K inhibition. Rapa treatment in mouse liver also decreased age-related activation of RelB and NF-κB2, core components of noncanonical NF-κB signaling. These findings define Stx12 as a downstream effector of TORC1–S6K signaling, highlighting a crucial role of the endolysosomal system in inflammaging, immunosenescence and longevity.

Results

S6K activity in the fat body is essential for longevity

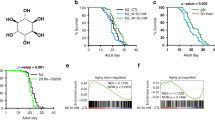

To address whether downregulation of S6K prolongs lifespan in Drosophila, we used the inducible GeneSwitch system in combination with an S6K RNAi line (Extended Data Fig. 1a) to knock down S6K expression specifically in adult female flies. Ubiquitous downregulation of S6K using a daGS driver resulted in a small but significant increase in lifespan (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1b), demonstrating that, as in Caenorhabditis elegans and mice16,28, reduced S6K can extend lifespan in Drosophila. To identify the tissue(s) in which reduced S6K acted to extend lifespan, we employed tissue-specific GeneSwitch drivers to suppress S6K in fat body (Lsp2GS), neurons (ElavGS), intestine (TiGS), muscle (MHCGS) and heart tube (HandGS) of adult flies. Repression of S6K activity in neurons and intestine did not affect lifespan (Extended Data Fig. 1c,d), while in muscle and heart tube it shortened it (Extended Data Fig. 1e,f). Lifespan was extended only upon fat-body-specific repression of S6K (Fig. 1b), indicating that S6K in the fat body is limiting for lifespan. Lifespan extension by Rapa can be blocked by ubiquitous S6K activation3. We therefore tested whether activating S6K just in fat body tissue was sufficient to block the effect of Rapa on survival. Administration of Rapa to flies that overexpressed a constitutively active S6K protein (S6KCA) specifically in the fat body, similar to ubiquitous activation (Fig. 1c), was sufficient to mostly block Rapa-mediated lifespan extension (Fig. 1d). The fat body is therefore a key tissue regulating survival downstream of TORC1 and S6K.

a, Adult-onset repression of S6K ubiquitously using daGS>S6KRNAi extended lifespan (P = 4.94 × 10−6, n = 150). b, Adult-onset repression of S6K in the fat body using Lsp2GS>S6KRNAi extended lifespan (n = 180). c, Rapa extended lifespan of control flies, but not of flies with ubiquitous overexpression of constitutively active S6K (daGS>S6KCA). Ubiquitous overexpression of constitutively active S6K significantly attenuated the response to Rapa treatment (Rapa: P = 2.04 × 10−5, daGS>S6KCA induction: P = 3.21 × 10−5, interaction P = 0.0236; n = 200). d, Adult-onset S6K activation in the fat body (Lsp2GS>S6KCA) significantly attenuated Rapa-related longevity (Rapa: P = 1.07 × 10−7, Lsp2GS>S6KCA induction: P = 1.58 × 10−5, interaction P = 0.0331; n = 200). log-rank test and CPH test. Representative survival curve of two independent assays.

S6K activity in the fat body does not regulate gut health

The Drosophila intestine plays a crucial role in TOR-dependent longevity11,29,30,31,32. Treating flies with Rapa improved gut health by increasing intestinal autophagy, reducing intestinal stem cell (ISC) turnover, age-related gut dysplasia and leakiness11,29,30,31. Considering the crosstalk between the fat body and the gut33,34, we tested whether modifying S6K activity in the fat body affected intestinal health. As expected, Rapa increased the number of lysosome- and autophagy-associated LysoTracker-positive puncta35 in the gut, but activation of S6K in the fat body did not block this increase (Extended Data Fig. 2a), suggesting that S6K activity in the fat body does not affect intestinal autophagy. Next, we performed phospho-histone H3 (pH3) immunostaining of fly guts, as a proxy for proliferating ISCs36. Neither elevated S6K activity in combination with Rapa nor reduced S6K level in the fat body affected the number of proliferating ISCs when compared to the respective controls (Extended Data Fig. 2b,c). Consistent with previous findings11,12, Rapa treatment protected against age-related gut dysplasia, but enhancing S6K activity in the fat body did not block this effect, nor was it reduced by fat-body-specific S6K repression (Extended Data Fig. 2d,e). In summary, lowered S6K activity in the fat body did not increase longevity by improving gut health.

Proteomics analysis of fat bodies with altered S6K activity

The Drosophila fat body is functionally equivalent to mammalian liver and white adipose tissue and is the central organ for metabolism and immune responses37. To gain further insight into the effects of TORC1–S6K signaling in the fat body, we used unbiased tandem mass tag (TMT)-based proteomic profiling of fat bodies from day 10 (young) and day 50 (old) flies with elevated S6K activity in fat bodies (Lsp2GS>S6KCA) in combination with Rapa treatment, or flies with repressed S6K level in fat bodies (Lsp2GS>S6KRNAi, Extended Data Fig. 3a). Principal component analysis revealed clear separation among age and treatment (Extended Data Fig. 3b). We detected a total of 4,101 proteins from the Lsp2GS>S6KCA proteomics assay and 4,809 proteins from the Lsp2GS>S6KRNAi proteomics assay (Supplementary Table 1). To explore S6K-dependent alterations in expression, we filtered the proteins that were significantly changed (P < 0.05) by both Rapa treatment and S6K manipulations, and these were associated with endocytosis, RNA binding processes and extracellular matrix in young fat bodies, and with mitochondria-, translation- and immune-related proteins in old fat bodies (Extended Data Fig. 3c and Supplementary Table 2).

To further enhance the resolution of our analysis, we conducted network propagation analysis38 to incorporate information on protein-protein interactions. We then identified functional categories and clustered them into age-related (Extended Data Fig. 3d), as well as Rapa-induced, S6K-dependent terms and S6K-inhibition-induced terms (Extended Data Fig. 3e). In old fat bodies, there was a marked upregulation of processes related to mitochondria, catalytic/metabolic activities and immune functions compared to young fat bodies. Conversely, there was a noticeable downregulation in ribosome-related processes, structural molecule activity and RNA binding (Extended Data Fig. 3d). Additionally, in young fat bodies, the inhibition of TORC1–S6K signaling led to an upregulation of processes associated with vesicle fusion, endosomes/lysosomes and translation, while processes related to oogenesis, the extracellular matrix and exocytosis were downregulated. In contrast, in the old fat bodies, inhibition of TORC1–S6K signaling resulted in an upregulation of terms related to translation, lysosomes and mitochondria, whereas immune functions, translation processes and respiratory chain complex activities were suppressed (Extended Data Fig. 3e).

S6K does not affect fecundity, translation or lipid storage

The fat body is important for oogenesis and reproduction, and reduced reproduction is often associated with increased longevity39. As oogenesis was identified as a significantly enriched term in the proteomics analysis (Extended Data Fig. 3e), we measured egg laying of females with fat-body-specific S6K downregulation and found that fecundity was not affected (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Reduced reproduction is therefore unlikely to contribute to S6K-related lifespan extension, consistent with the findings for Rapa3.

S6K is a regulator of protein synthesis, and protein translation was identified as an enriched term in the proteomics analysis (Extended Data Fig. 3e). Furthermore, reduced protein synthesis has been associated with longevity in several invertebrate longevity models. To address whether S6K or Rapa affected global protein synthesis in the fly fat body, we performed puromycin incorporation assays. Although Rapa treatment repressed phosphorylation of S6K at Thr398 (pS6K) and activation of S6K elevated both pS6K and total S6K level, puromycin incorporation was not affected by Rapa treatment nor by S6K activation upon Rapa feeding (Extended Data Fig. 4b), suggesting that TORC1–S6K signaling does not change global translation rates in fat bodies. Consistently, deletion of S6K and chronic Rapa feeding also had no effect on global translation rates in mice40,41. TORC1 specifically controls translation of proteins that contain a 5′-terminal oligopyrimidine motif (5′TOP) in their messenger RNA34. Accordingly, although proteins with a 5′TOP motif in their mRNA were significantly downregulated in the fat body of Rapa treated animals, activation of S6K did not block this effect (Extended Data Fig. 4c), consistent with previous findings42,43.

Lipid metabolism has been implicated in the aging process44, and Rapa increases lipid storage in flies3. However, S6K activation did not alter Rapa-induced triglyceride accumulation in the fat body (Extended Data Fig. 4d). Moreover, repressing S6K in the fat body did not affect survival under starvation, and ubiquitous S6K activation did not attenuate Rapa-induced starvation resistance (Extended Data Fig. 4e,f). Thus, TORC1–S6K-dependent longevity cannot be explained by an effect on triglyceride accumulation.

TORC1–S6K signaling affects lysosomal morphology

Lysosome-related annotations were upregulated with the inhibition of TORC1–S6K activity in the young fat body (Extended Data Fig. 3e). Rapa treatment increased the number of LysoTracker-positive puncta in fat body cells (Fig. 2a, ‘Total LTR puncta’). Surprisingly, activation of S6K did not attenuate this increase, and instead led to a substantial accumulation and enlargement of acidic organelles (Fig. 2a). These S6K-dependent enlarged organelles were identified as lysosomes as indicated by a GFP–Lamp1 reporter45, and late endosomes, indicated by a YFP–Rab7 reporter (Fig. 2b). To measure changes in lysosomes directly, we used a Lamp1–3xmCherry reporter46, which marks lysosomes by an endogenous, promoter-driven, C-terminally mCherry-tagged Lamp1. mCherry-labeled lysosomes appeared as large puncta in fat bodies with S6K activation co-treated with Rapa (Extended Data Fig. 5a). Electron microscopy showed enlarged LysoTracker-positive puncta upon S6K activation as multilamellar lysosomes (Fig. 2c). However, large LysoTracker-positive puncta upon Rapa treatment were mainly due to the accumulation of more electron-dense lysosomes (Extended Data Fig. 5b). Thus, Rapa and S6K activation combined induce LysoTracker-positive puncta by two distinct mechanisms combined. Importantly, the ratio of multilamellar to total lysosomal area was ameliorated by Rapa treatment in an S6K-dependent manner (Fig. 2c). The multilamellar lysosomes suggests impaired lysosomal fusion or defective membrane function, which is typical of lysosomal storage diseases47. Thus, we next addressed lysosomal degradation capacity by performing a DQ–BSA (dye quenched-bovine serum albumin)/FITC–BSA (fluorescein isothiocyanate-bovine serum albumin) pulse-chase assay (Fig. 2d). Upon cleavage in the lysosome, DQ–BSA emits fluorescence. Rapa treatment resulted in an increased fluorescent signal, which was blocked by activation of S6K (Fig. 2d). Therefore, downregulation of TORC1 increased lysosomal degradation capacity in the fat body in an S6K-dependent manner.

a, LysoTracker staining of fat bodies from young (day 10) flies. Fat-body-specific, adult-onset overexpression of constitutively active S6K (Lsp2GS>S6KCA) significantly increased acidic organelle amount and size in response to Rapa treatment (total puncta: Rapa: P = 1.338 × 10−6, Lsp2GS>S6KCA induction: P = 0.0001, interaction P = 0.0946; large puncta: Rapa: P = 2.896 × 10−5, Lsp2GS>S6KCA induction: P = 1.618 × 10−5, interaction P = 0.0246; n = 12). b, LysoTracker-positive enlarged acidic organelles (magenta) colocalized with the lysosomal marker Lamp1 (Lsp2GS>S6KCA;GFP–Lamp1, green, top) and partially colocalized with Rab7 (Lsp2GS>S6KCA;YFP–Rab7, green, bottom), a marker for late endosomes, in young flies treated with Rapa and overexpressing S6KCA. c, Electron microscopy (EM) images of fat bodies of young flies treated with Rapa and overexpressing S6KCA. Overexpression of S6KCA in the fat body attenuated the effect of Rapa on the ratio of multilamellar to total lysosomal area (Rapa: P = 0.0395, Lsp2GS>S6KCA induction: P = 0.2798, interaction P = 0.0388; n = 5). d, Rapa increased lysosomal degradation capacity in the fat body of young flies, depicted by DQ–BSA/FITC–BSA pulse-chase assay. Lysosomes were labeled by FITC–BSA. Overexpression of S6K (Lsp2GS>S6KCA) blocked the effect of Rapa on lysosomal degradation capacity (Rapa: P = 0.3278, Lsp2GS>S6KCA induction: P = 0.1382, interaction P = 0.0051; n = 14) in fat bodies of young flies. e, LysoTracker staining of young fat bodies overexpressing dominant negative Rab7 (Lsp2GS>Rab7DN). Fat-body-specific overexpression of Rab7DN significantly increased acidic organelle size (P = 0.0064; n = 12). f, Fat-body-specific overexpression of dominant negative Rab5 (Lsp2GS>Rab5DN) also increased acidic organelle size (P = 0.0798; n = 12). For box plot (a and d–f), the center is the median, the lower and upper bounds correspond to the first and third quartiles, the whiskers extend up to 1.5 times the interquartile range, and the minima and maxima are the observed minima and maxima. Data are displayed as mean ± s.e.m. (c). Each data point represents an average value per fat body. Two-sided linear mixed model (a and d–f) or two-sided negative binomial generalized linear model (c) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Scale bar, 10 μm (a, b and d–f) or 1 μm (c).

Lysosome biogenesis is a crucial mechanisms for regulating lysosome number and size48. Transcription factor EB (TFEB, termed Mitf in Drosophila) is a master regulator of lysosomal biogenesis. To test whether Mitf plays a role in S6K-dependent lysosomal enlargement we downregulated Mitf in fat bodies, but this did not block the formation of large LysoTracker-positive punctae in S6KCA-expressing flies treated with Rapa (Extended Data Fig. 6a). The lysosome is the terminal compartment for autophagy and endocytosis48. As autophagy plays a vital role during aging9, we investigated if defective autophagy caused the TORC1–S6K-dependent lysosomal changes. Consistent with previous findings3, repressing autophagy induction by Lsp2GS>Atg5RNAi blocked Rapa-induced accumulation of LysoTracker-positive organelles in the fat body (Extended Data Fig. 6b), indicative of perturbed autophagy. However, the number of enlarged LysoTracker-positive organelles induced by S6K activation with Rapa treatment was not changed upon inhibition of Atg5 (Extended Data Fig. 6c), suggesting that the S6K-dependent lysosomal enlargement was not caused by autophagy dysfunction.

TORC1–S6K-dependent enlarged LysoTracker-positive organelles were partially colocalized with late endosomes (Fig. 2b). Thus, we next investigated if interfering with the endocytosis pathway would cause lysosomal enlargement. We impaired late endosome formation by expressing dominant-negative (DN) Rab7 (Lsp2GS>Rab7DN), which led to enlarged LysoTracker-positive organelles (Fig. 2e). Moreover, perturbation of early endosomes by DN Rab5 (Lsp2GS>Rab5DN) also mildly induced LysoTracker-positive organelle enlargement (Fig. 2f). In summary, interfering with endosomes but not autophagy caused a similar lysosomal phenotype as activation of S6K, suggesting that TORC1–S6K regulates lysosomal morphology via modulation of the endolysosomal system.

S6K controls lysosomal structure through Syx13

Proteins associated with vesicle fusion and vesicle membrane-related processes were regulated by TORC1–S6K signaling in the proteomics analysis (Extended Data Fig. 3e). Among them, protein levels of the SNARE protein Syx13 were upregulated both upon S6K knockdown and by Rapa treatment (Fig. 3a,b and Supplementary Table 2). Furthermore, the increase in Syx13 protein levels upon Rapa feeding was blocked upon activation of S6K (Fig. 3a), suggesting Syx13 as a potential downstream effector of TORC1–S6K in regulating lysosomal morphology. Consistent with this hypothesis, repression of Syx13 in young fat bodies caused lysosomal enlargement (Fig. 3c). In contrast, overexpression of Syx13 did not alter lysosomal morphology under basal conditions (Fig. 3d). To determine whether Syx13 was causally associated with the S6K-induced changes in lysosomal morphology, we increased both Syx13 expression and S6K activity in the fat body of flies that were treated with Rapa. Co-overexpression of Syx13 did not affect the efficiency of S6K overexpression (Extended Data Fig. 7a), but S6K-induced enlarged lysosomes (Fig. 3e and Extended Data Fig. 7b) and the associated multilamellar structure (Fig. 3f) were both diminished by Syx13 overexpression. Therefore, TORC1–S6K–Syx13 signaling mediated the lysosomal structural changes.

a, Syx13 protein level was increased upon Rapa treatment in young fat body cells, and this increase was partly reverted by S6K overexpression (Lsp2GS>S6KCA; Rapa: P = 0.0003, Lsp2GS>S6KCA induction: P = 0.0138, interaction P = 0.0086; n = 5). b, Syx13 protein level was increased upon S6K repression (Lsp2GS>S6KRNAi; P = 0.0226; n = 5) in young fat body cells. Syx13 protein levels were measured by mass spectrometry-based proteomics. c, Knockdown of Syx13 expression (Lsp2GS>Syx13RNAi) resulted in enlarged lysosomes in the fat body of young flies, depicted by LysoTracker staining (P = 0.0057; n = 14). d, Overexpression of Syx13 (Lsp2GS>Syx13) did not affect lysosomal enlargement (P = 0.2894; n = 12) in young fat bodies. e, Overexpression of Syx13 (Lsp2GS>S6KCA;Syx13) rescued the enlarged lysosomes of flies overexpressing S6K (Lsp2GS>S6KCA) treated with Rapa (Lsp2GS>S6KCA induction: P = 5.559 × 10−5, Lsp2GS>Syx13 induction: P = 6.083 × 10−5, interaction P = 0.0429; n = 12). f, Overexpression of Syx13 (Lsp2GS>S6KCA;Syx13) partially rescued the multilamellar lysosomes of S6K overexpressing (Lsp2GS>S6KCA) flies treated with Rapa, depicted by electron microscopy (Lsp2GS>S6KCA induction: P = 0.0005, Lsp2GS>Syx13 induction: P = 0.7989, interaction P = 0.3068; n = 5). Data are displayed as mean ± s.e.m. (a, b and f). For box plot (c–e), the center is the median, the lower and upper bounds correspond to the first and third quartiles, the whiskers extend up to 1.5 times the interquartile range, and the minima and maxima are the observed minima and maxima. Each data point represents an average value per five fat bodies (a and b) or per fat body (c–f). Two-sided linear mixed model (a–e) or two-sided negative binomial generalized linear model (f) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Scale bar, 10 μm (c–e) or 1 μm (f).

S6K regulates inflammaging and immunosenescence

Lysosomal function plays a crucial role in inflammatory and autoimmune disorders49. A growing body of evidence has established that aging can lead to a low-grade inflammation that is associated with increased mortality22,50,51. The fat body is a major immune organ of Drosophila, and the proteins upregulated in old fat bodies that were altered by TORC1–S6K signaling showed significant enrichment of immune-related Gene Ontology (GO) annotations (Extended Data Fig. 3d,e). Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are key defense molecules of the Drosophila innate immune system, and their levels in fat body increased with age and were reduced upon Rapa treatment in old animals (Fig. 4a). Activation of S6K abolished the Rapa effect on attacins (AttC and AttB) and diptericin (DptA), which are primarily controlled by the immune deficiency (IMD) pathway. These AMPs were also reduced by S6K inhibition in old fat bodies, suggesting that the activity of the IMD pathway might be influenced by TORC1–S6K signaling during aging.

a, log2 fold change (FC) across age and treatments of all AMPs detected in the fat body proteome. All AMPs accumulated with age and were repressed by Rapa treatment; S6K activation specifically blocked the effects of Rapa AMPs (AttC, AttB and DptA) downstream of the IMD pathway. AMPs associated with the IMD pathway were also repressed by S6K inhibition. b, Cleaved Relish (Rel49, 49 kDa) in fat bodies of young (day 10), middle (day 30) and old (day 50) flies (age effect P = 0.0034; n = 4). c,d, Relish (Rel) protein localization (c, n = 9 in young and n = 13 in old) and DptA transcript expression (d, n = 4) in fat bodies of young and old flies. e–g, S6K inhibition (Lsp2GS>S6KRNAi) suppressed the age-related increase in activated Rel49 (e, n = 5), accumulation of Relish in the nucleus (f, n = 14), and the increase in DptA expression (g, n = 3) in fat bodies of old (day 50) flies. h,i, Rapa treatment suppressed age-related Relish localization (h) and the increase in DptA (i). Overexpression of S6K (Lsp2GS>S6KCA) blocked the effect of Rapa on Relish localization (h, Rapa: P = 0.0025, Lsp2GS>S6KCA induction: P = 1.339 × 10−6, interaction P = 0.2345; n = 14) and DptA expression (i, n = 4) in fat bodies of old (day 50) flies. j, Rapa treatment improved bacterial clearance in old (day 50) flies infected with Ecc15, indicated by colony forming unit (CFU) assay. This effect was blocked by S6K overexpression (Lsp2GS>S6KCA) (Rapa: P = 0.0185, Lsp2GS>S6KCA induction: P = 0.0024, interaction P = 0.0620; n = 12). Data are displayed as mean ± s.e.m. (b, d, e, g and i). For box plot (c, f, h and j), the center is the median, the lower and upper bounds correspond to the first and third quartiles, the whiskers extend up to 1.5 times the interquartile range, and the minima and maxima are the observed minima and maxima. Each data point represents an average value per fat body (c, f and h), per five fat bodies (b, d, e, g and i) or per three whole flies (i). Two-sided one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (b). Two-sided linear mixed model (c, f and h) or two-sided two-way ANOVA with log transformation (j) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Two-sided Student’s t-test with (d, g and i) or without log-transformation (e). Scale bar, 10 μm.

In Drosophila, the IMD pathway is the primary immune response pathway. When activated, the NF-κB-like transcription factor Relish is cleaved in the cytoplasm, and the activated fragment of Relish translocates to the nucleus and induces the transcription of AMPs, such as DptA (refs. 33,52,53). In line with previous reports33,54,55, aged fat bodies exhibited elevated Relish cleavage (Fig. 4b), Relish-positive nuclei (Fig. 4c) and DptA expression (Fig. 4a,d), indicating that IMD signaling was activated during aging. These changes were significantly ameliorated by reduced S6K activity (Fig. 4e–g). Furthermore, Rapa treatment greatly suppressed the age-associated changes in Relish localization and DptA expression in fat bodies, while activation of S6K blocked these effects (Fig. 4h,i). Immunosenescence also occurs during aging, with a declining ability of old flies to clear pathogens56,57. We therefore investigated whether S6K plays a role in bacterial clearance upon systemic infection with Ecc15, a Gram-negative bacterium widely used to study Drosophila immune responses58. Rapa treatment increased bacterial clearance in old flies, and expression of S6KCA specifically in fat bodies blocked this effect (Fig. 4j). These results suggest that TORC1–S6K signaling regulates age-associated activation of the IMD pathway and the decline of pathogen clearance.

Potential mechanisms of age-associated immune activation include increased intestinal permeability, chronic infection and ‘sterile inflammation’ caused by internal factors22,59. We next investigated whether S6K directly regulates IMD activation upon microbial infection. We therefore challenged young fat bodies ex vivo with Ecc15. Although Ecc15 infection led to a clear induction in the number of Relish-positive nuclei under basal conditions, knockdown of S6K failed to repress this induction (Extended Data Fig. 8a), suggesting that the effect of S6K on the IMD pathway is indirect and dependent on age-dependent changes in fat bodies. We next explored whether activation of the IMD pathway by TORC1–S6K signaling is dependent on age-associated accumulation of bacteria60. Therefore, flies were treated with antibiotics from young age to eliminate bacterial accumulation during aging. Colony unit forming assay indicated that the antibiotic treatment dramatically reduced bacterial growth (Extended Data Fig. 8b). However, Rapa treatment still repressed the number of Relish-positive nuclei and DptA expression in an S6K-dependent manner (Extended Data Fig. 8c,d). These results show that TORC1–S6K signaling regulates age-associated activation of the IMD pathway independent of bacterial load.

Endolysosomes mediate the Rapa effects on inflammaging

Given that TORC1–S6K–Syx13 signaling regulated lysosomal morphology, we hypothesized that age-related IMD activation in fat bodies could be an outcome of endolysosomal dysfunction. We therefore investigated if the endocytosis pathway contributes to TORC1–S6K-related regulation of Relish. Overexpression of DN Rab7 blocked the Rapa-induced decrease in the number of Relish-positive nuclei in the aged fat body (Fig. 5a). Moreover, impairment of early endosomes by expression of DN Rab5 attenuated TORC1-related Relish repression (Fig. 5b), suggesting that the endolysosomal system acts downstream of TORC1–S6K in regulating IMD activity.

a,b, Rapa treatment suppressed the age-related nuclear localization of Relish (Rel) in old fat body cells. Dominant-negative Rab7 (a, Rapa: P = 0.0638, Lsp2GS>Rab7DN induction: P = 4.149 × 10−6, interaction P = 0.0160; n = 14) and Rab5 (b, Rapa: P = 4.467 × 10−6, Lsp2GS>Rab5DN induction: P = 7.276 × 10−6, interaction P = 0.0003; n = 14) blocked the effect of Rapa on the age-related nuclear localization of Relish. c,d, Removing the full-length PGRP-LC (PGRP-LCΔE12) and only the regulatory PGRP-LC isoforms by deleting exon 5 (resc(LCΔex5)) repressed the age-related nuclear localization of Relish and Rapa effect in the fat body of old flies treated with antibiotic (c, Rapa: P = 0.0355, PGRP-LCΔE12: P = 7.925 × 10−9, interaction P = 0.0569; n = 9 in PGRP-LCΔE12 group and n = 14 in other groups; d, Rapa: P = 0.1642, resc(LCΔex5): P = 0.0028, interaction P = 0.0018; n = 14). e, Overexpression of regulatory PGRP-LC isoform (Lsp2GS>GFP–rLCx) suppressed the Rapa effect on Relish localization in old fat body cells (Rapa: P = 0.1921, Lsp2GS>GFP–rLCx induction: P = 0.0432, interaction P = 2.285 × 10−5; n = 14). f, Overexpression of canonical PGRP-LC isoform (Lsp2GS>LCx), did not affect the Rapa effect on Relish localization in old fat body cells (Rapa: P = 1.419 × 10−8, Lsp2GS>LCx induction: P = 0.8768, interaction P = 0.3832; n = 14). g, Overexpression of regulatory PGRP-LC isoform (Lsp2GS>GFP–rLCx) did not affect the nuclear localization of Relish in young (left, n = 14) and old (right, n = 14) fat body cells, but induced the nuclear localization of Relish in middle-aged (middle, n = 14) fat body cells. Time course experiments were performed separately using the same batch of flies. h, Regulatory PGRP-LC (green) colocalized with LysoTracker-positive enlarged acidic organelles (magenta) in the fat body of young flies treated with Rapa and overexpressing S6KCA (Lsp2GS>S6KCA;GFP–rLCx, n = 14). For box plot, the center is the median, the lower and upper bounds correspond to the first and third quartiles, the whiskers extend up to 1.5 times the interquartile range, and the minima and maxima are the observed minima and maxima. Each data point represents an average value per fat body. Two-sided linear mixed model followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Disrupting endosomal trafficking induces the accumulation of cytokine receptors and subsequently activates the IMD/NF-κB pathway in fly fat bodies61 and in human cells62. Peptidoglycan recognition protein LC (PGRP-LC) is a key upstream receptor of the IMD pathway in flies53. Loss of PGRP-LC strongly reduced the number of Relish-positive nuclei and there was no additional effect of Rapa treatment (Fig. 5c), suggesting a vital role of PGRP-LC in inflammaging. The PGRP-LC gene is a complex locus that produces both activating isoforms (PGRP-LC; LC, including LCx, LCy and LCa) and regulatory isoforms (rPGRP-LC; rLC, including rLCx, rLCy and rLCa)61. To address which isoform underlies the observed phenotype, we used a mutation that specifically deleted rPGRP-LC. Interestingly, lack of just the regulatory isoform was sufficient to block age-related accumulation of Relish-positive nuclei (Fig. 5d), similar to the complete removal of the PGRP-LC gene (Fig. 5c). Furthermore, overexpression of the regulatory isoform rPGRP-LC, but not of canonical PGRP-LC, blocked the effect of Rapa on age-related nuclear accumulation of Relish (Fig. 5e,f), suggesting rPGRP-LC as a driver of inflammaging in the fly fat body. This finding was surprising, as rPGRP-LC has been shown to have an anti-inflammatory function upon acute infection in young flies61. Consistent with this hypothesis, overexpression of rPGRP-LC did not affect nuclear localization of Relish in young flies (Fig. 5g). However, prolonged overexpression of rPGRP-LC induced accumulation of Relish in middle-aged flies, indicating that it can induce inflammation in an age-dependent manner. There was no additional effect of rPGRP-LC expression observed in old flies, probably due to the already very high level of Relish nuclear accumulation. Having identified rPGRP-LC as a driver of inflammaging, we next used a GFP-tagged rPGRP-LC protein to address its subcellular localization in fat body cells. Interestingly, GFP–rPGRP-LC protein accumulated in enlarged lysosomes induced by activation of S6K and Rapa treatment (Fig. 5h), suggesting reduced degradation by the endolysosome. These results suggest that inflammaging in flies is induced by rPGRP-LC and controlled by its endolysosome-dependent degradation.

TORC1–S6K–Syx13 mediates inflammaging and immunosenescence

Given the vital role of Syx13 in the endolysosomal system, we next investigated if Syx13 acts downstream of TORC1–S6K to regulate immune aging. Knockdown of Syx13 caused a robust induction in the number of Relish-positive nuclei in old fat bodies and blocked the effects of Rapa on Relish-positive nuclei and bacterial clearance (Fig. 6a,e). Relish repression upon S6K knockdown was also rescued by reducing Syx13 expression (Fig. 6b). Overexpression of Syx13 limited age-associated Relish activation and extended lifespan (Fig. 6c,i). Furthermore, while S6K activation blocked the effects of Rapa on Relish-positive nuclei, bacterial clearance and lifespan, co-overexpression of Syx13 restored the effects of Rapa (Fig. 6d,f,h and Extended Data Fig. 7c). Thus, Syx13 acts downstream of TORC1 and S6K to regulate inflammaging and immunosenescence. Despite the finding that autophagy can control inflammation and longevity63, blocking autophagy by Atg5-RNAi in the fat body did not block Rapa-dependent repression of Relish-positive nuclei and longevity (Extended Data Fig. 6d,e). Taken together, these findings show that TORC1–S6K–Syx13 signaling regulates immune aging via the endolysosomal system.

a,b, Knockdown of Syx13 blocked the effect of Rapa (a, Rapa: P = 0.0012, Lsp2GS>Syx13RNAi induction: P = 1.026 × 10−10, interaction P = 0.2930; n = 14) and S6K knockdown (b, Lsp2GS>S6KRNAi induction: P = 0.0004, Lsp2GS>Syx13RNAi induction: P = 5.699 × 10−7, interaction P = 0.0088; n = 14) on Relish (Rel) nuclear localization in old fat body cells. c, Overexpression of Syx13 (Lsp2GS>Syx13; n = 14) repressed the age-related nuclear localization of Relish in old fat body cells. d, Overexpression of Syx13 (Lsp2GS>S6KCA;Syx13) rescued the effect of S6K activation on Relish localization (Lsp2GS>S6KCA induction: P = 2.796 × 10−5, Lsp2GS>Syx13 induction: P = 1.139 × 10−10, interaction P = 8.787 × 10−9; n = 14) in old flies treated with Rapa. e, Knockdown of Syx13 (Lsp2GS>Syx13RNAi) blocked the effect of Rapa on bacterial clearance, indicated by colony forming unit (CFU) assay (Rapa: P = 0.0093, Lsp2GS>Syx13RNAi induction: P = 0.0057, interaction P = 0.2226; n = 8). f, Overexpression of Syx13 (Lsp2GS>S6KCA;Syx13) rescued the effect of S6K activation on bacterial clearance (Lsp2GS>S6KCA induction: P = 0.0644, Lsp2GS>Syx13 induction: P = 0.7042, interaction P = 0.0429; n = 10) in old flies treated with Rapa. g, Middle-age-onset repression of Relish using Lsp2GS>RelishRNAi improved bacterial clearance in old flies (n = 8 in 0 h.p.i. group and n = 12 in 12 h.p.i. groups). h, Overexpression of Syx13 (Lsp2GS>S6KCA;Syx13) increased the lifespan of flies with S6K activation (Lsp2GS>S6KCA induction: P = 0.1504, Lsp2GS>Syx13 induction: P = 0.0148, interaction P = 0.2410; n = 200) i,j, Overexpression of Syx13 (i, Lsp2GS>Syx13; n = 200) and middle-age-onset repression of Relish (j, Lsp2GS>RelishRNAi; n = 200) extended lifespan. For box plot, the center is the median, the lower and upper bounds correspond to the first and third quartiles, the whiskers extend up to 1.5 times the interquartile range, and the minima and maxima are the observed minima and maxima. Each data point represents an average value per fat body (a–d) or per three whole flies (e–g). Two-sided linear mixed model (a–d) or two-sided two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with log transformation (e and f) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Two-sided Student’s t-test (g). CPH test and log-rank test (h–j). Representative survival curve of one (h) or two independent assay(s) (i and j). Scale bar, 10 μm.

Inflammaging in fly fat body is sex dependent

Knockout of S6K1 increased lifespan specifically in female but not in male mice16, suggesting a sex-specific role of S6K in the regulation of lifespan. Consistent with the mammalian finding, downregulation of S6K did also not increase lifespan in male flies (Extended Data Fig. 1b). To dissect the molecular mechanisms associated with the sex-specific effect of TORC1–S6K signaling, we first performed LysoTracker staining (Extended Data Fig. 9a). As in females, Rapa treatment also increased the number of LTR-positive punctae in fat bodies of males (Extended Data Fig. 9a). Furthermore, S6K activation in combination with Rapa treatment resulted in the accumulation of enlarged lysosomes in the fat body of both sexes (Extended Data Fig. 9a). Thus, changes in lysosomal morphology cannot explain the sex-specific lifespan difference. We next measured inflammation in old fat bodies of males and females (Extended Data Fig. 9b). Notably, old males had significantly less nuclear Relish than females, suggesting lower levels of inflammaging in the old male fat body, and neither Rapa treatment nor S6K activation affected nuclear localization of Relish, (Extended Data Fig. 9b). Thus, sex-specific differences in fat body inflammaging may contribute to the observed lifespan effects of S6K in males and females.

Relish in fat bodies controls immunosenescence and longevity

Given that TORC1–S6K signaling regulated age-associated immune dysfunctions, we next addressed whether inflammaging in fat bodies affects pathogen clearance and longevity. Downregulating Relish level in fat bodies from middle-age on significantly improved bacterial clearance and extended female lifespan (Fig. 6g,j), demonstrating that ameliorating inflammaging may contribute to efficient clearance of bacteria at old age and lifespan extension.

TORC1–S6K regulates Stx12 and immunoaging in mice

Syx13 levels were upregulated in fly fat bodies upon downregulation of TORC1–S6K signaling (Fig. 3a,b). Interestingly, Syx13 levels were also upregulated in long-lived S6K mutant worms28 and in Rapa-treated yeast64, suggesting that this regulation is evolutionarily conserved, at least among yeast, worms and flies. In line with the findings in invertebrates, chronic Rapa treatment significantly increased Stx12 protein levels in the liver of female mice (Fig. 7a), suggesting that the TORC1-associated regulation of Stx12 is conserved from yeast to mammals.

a, Rapa treatment increased Stx12 level in the liver of 12-month-old mice (n = 7). b, Schematic for the analysis workflow. Common genes present in all three datasets were used for network propagation and GO analysis. c, Only GO terms significantly regulated (P < 0.05, Fisher tests) in the same direction in all three datasets are shown. Immune-related annotations are shown in blue. Cells are colored by their log10 significance score. d, All NF-κB-targeted genes detected in all three datasets are shown. Cells are colored by their log2 fold change (FC). e, The effect of age and Rapa on the activity of the canonical NF-κB pathway as indicated by RelA/p65 level in liver subcellular fractions from 12-month-old (‘Middle’) and 24-month-old (‘Old’) mice (for nuclear fraction (‘Nuc’): age effect P = 0.0504, Rapa effect P = 0.4886, interaction P = 0.7559; for cytosolic fraction (‘Cyt’): age effect P = 0.9721, Rapa effect P = 0.7437, interaction P = 0.4936; n = 4). f,g, The effect of age and Rapa on the activity of the noncanonical NF-κB pathway as indicated by RelB level (f, for nuclear fraction (‘Nuc’): age effect P = 0.1050, Rapa effect P = 0.0680, interaction P = 0.0944; for cytosolic fraction (‘Cyt’): age effect P = 0.0310, Rapa effect P = 0.5382, interaction P = 0.8136; n = 4) and by NF-κB2/p52 level (g, for nuclear fraction (‘Nuc’): age effect P = 0.1218, Rapa effect P = 0.0405, interaction P = 0.0630; for cytosolic fraction (‘Cyt’): age effect P = 0.7063, Rapa effect P = 0.2032, interaction P = 0.0636; n = 4) in the liver subcellular fractions from 12-month-old (‘Middle’) and 24-month-old (‘Old’) mice. Data are displayed as mean ± s.e.m. Two-sided one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (a). Two-sided two-way ANOVA followed by Šídák’s multiple comparison test for comparison within nuclear fraction and cytosolic fraction separately (e–g).

To address whether reduced TORC1–S6K signaling also affected immunoaging in mice, we performed proteomics profiling of old liver samples from long-lived mice treated with Rapa (Supplementary Table 4) and integrated these data with previously published transcriptome analyses of livers of aged mice with Rapa treatment or S6K1 deficiency16,65 (Fig. 7b). Network propagation analysis38 of the 4,340 proteins shared between the three datasets identified immune-related processes, including inflammation and leukocyte proliferation, as commonly downregulated by S6K deficiency or Rapa treatment, while lipid- and translation-related processes were enhanced (Fig. 7c and Supplementary Table 5). In flies, the NF-κB-like transcription factor Relish was downregulated upon TORC1 repression in a S6K-dependent manner. Thus, we next explored the changes of NF-κB signaling in old liver. Consistent with the findings in Drosophila, NF-κB-target genes were generally repressed in old liver upon TORC1–S6K inhibition, including genes crucial for inflammatory responses, such as galectin-3 (Lgals3)66, interferon regulatory factor 2 (Irf2)67, proteasome subunit beta 9 (Psmb9)68, interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (Il1rn)69, C-reactive protein (Crp)70 and TNF receptor-associated factor 2 (Traf2)71 (Fig. 7d).

In mammals, activation of NF-κB signaling involves a canonical and noncanonical pathway branch that lead to the nuclear translocalization of the RelA/NF-κB1 dimer or the RelB/NF-κB2 dimer72, respectively. Nuclear/cytosol fractionation coupled with western blot showed that RelA, the canonical NF-κB transcription factor, was primarily localized in the cytosol and was unaffected by aging or Rapa (Fig. 7e). In contrast, the noncanonical NF-κB transcription factors, RelB and NF-κB2, were mainly in the nuclei of old liver and reduced by Rapa treatment (Fig. 7f,g), suggesting age-related activation of noncanonical NF-κB signaling in the mouse liver that can be counteracted by Rapa treatment.

Discussion

Although S6K is a key downstream effector of mTOR signaling and has been implicated in determination of lifespan in invertebrates and mammals, the molecular and cellular mechanisms are still elusive. Here we show that, in Drosophila, lowered activity of S6K in the fat body is essential for mTOR-dependent longevity, and that it regulates endolysosomal morphology, inflammaging and immunosenescence in the aging fat body. Modifying endosome formation, but not autophagy, affected inflammaging by degrading rPGRP-LC, suggesting a causal link between endolysosome and inflammaging. We identified Syx13 as a molecular link that regulates endosome formation, inflammaging and lifespan downstream of TORC1–S6K signaling. We uncovered a considerable sexual dimorphism in fat body inflammaging, potentially explaining the different lifespan impacts of S6K observed in males and females. Furthermore, repression of the NF-κB-like IMD pathway in the fly fat body enhanced clearance of bacteria and extended lifespan. Importantly, long-term treatment with Rapa increased Stx12 levels in mouse liver, and alleviation of immune processes was a common denominator of TORC1–S6K inhibition in RNA and proteomics profiles from the liver of old Rapa-treated and S6K1 null mice. Furthermore, Rapa lowered age-associated activation of noncanonical NF-κB pathway in mouse liver, indicating that the effects of TORC1–S6K–Stx12 on immunoaging may be evolutionarily conserved from flies to mice. In summary, our findings highlight an important role for the TORC1–S6K–Syx13 signaling axis in inflammaging, immunosenescence and longevity (Extended Data Fig. 10).

Deletion of S6K increases lifespan in worms and of S6K1 does so in female mice16,28. In Drosophila, deletion of S6K is developmental lethal, but overexpression of a kinase-dead S6K has also been shown to extend adult lifespan73. However, whether this lifespan extension was caused by a loss in S6K activity or by titration of the Raptor protein, a key component of the TORC1 complex that directly interacts with S6K via the Raptor-binding TOS motif, was not clear74. We found that RNAi-mediated downregulation of S6K ubiquitously and in the fat body, but not in the intestine, neurons, muscle or heart extended lifespan to a similar extent, establishing the fat body as the key tissue for S6K-mediated longevity. Consistently, fat-body-specific overexpression of a constitutively active S6K protein blocked the effect of Rapa on longevity, demonstrating that lowered S6K activity in the fat body is essential for TORC1-mediated lifespan extension. In mice, phosphorylation of glutamyl-prolyl-tRNA synthetase (EPRS) has been linked to the effects of S6K1 deletion on adiposity and lifespan8. However, the Drosophila EPRS sequence lacks the mammalian EPRS phosphorylation site for S6K1. Furthermore, we did not find a role for S6K in Rapa-mediated lipid storage. S6K and autophagy are both essential for lifespan extension upon TORC1 inhibition4. However, while S6K function is required in the fat body but not in the gut, autophagy is essential in the gut and not the fat tissue8. Although the gut has recently been identified as a key organ in determining health and longevity11,12,75, our results suggest that the S6K-dependent phenotypes that we observed are independent of gut health.

Rapa treatment or the removal of S6K prolongs the lifespan of female animals more than males4,16,32, suggesting an evolutionarily conserved, sexually dimorphic aspect of longevity mechanisms. In line with the observation that genes related to the noncanonical NF-κB pathway are more abundant in the aged livers of female mice compared to male mice76, we have noted relatively higher levels of inflammaging in fat bodies of female flies compared to males, which can be further mitigated by inhibiting TORC1–S6K signaling. Given that suppressing inflammaging extended lifespan in female flies, the sex-specific age-prolonging effects of S6K may stem from its positive impact on inflammaging in female flies. Importantly, we found that S6K modulated lysosomal morphology, a key factor in both inflammaging and lifespan, in both sexes. This finding suggests that, while endolysosome-dependent regulation of inflammaging is crucial in female flies, male flies may possess distinct unknown mechanisms for controlling age-related inflammation.

Lysosomes are key to cellular proteostasis, and dysfunction of lysosomes contributes to age-associated pathologies9. Using LysoTracker staining and electron microscopy we observed a strong increase in lysosomal size associated with multilamellar structures in fat bodies expressing activated S6K and treated with Rapa. These changes are reminiscent of lysosomal storage diseases47, and may indicate impaired function caused by defects in lysosome or membrane fusion. These changes in the lysosome were rescued by overexpression of Syx13, a SNARE family protein that regulates autophagosome maturation and vesicle fusion77,78. Knockdown of Syx13 in human cells also induces multilamellar lysosome-like organelles25, suggesting evolutionary conservation of this function between flies and humans. Furthermore, Syx13 levels were upregulated in long-lived S6K mutant worms28 and also in Rapa-treated yeast64, flies and mice, suggesting that the regulation of Syx13 by TORC1 via S6K is evolutionarily conserved among these species. Protein expression of Syx13 has been shown to be positively regulated by short-term TORC1 inhibition upon neuronal injury or in mammalian cell culture42,79,80, possibly indicating a difference between acute stress and chronic inhibition of the mTOR pathway. Noteworthy, in contrast to Rapa feeding, Syx13 levels were not decreased upon activation of S6K under untreated control conditions and were even slightly upregulated, which might reflect a compensatory response upon S6K activation to counteract the detrimental effects of S6K on lysosome function.

Maintaining lysosomal function with age improves healthspan and lifespan in diverse animals10,13,81,82,83, effects so far mainly attributed to increased autophagy9,84. In contrast, we found that TORC1–S6K signaling regulates age-associated activity of the NF-κB-like transcription factor Relish and AMP expression via the endolysosomal system in the fat body, the main immune-responsive tissue of Drosophila. Age-associated inflammation could be caused by external factors like pathogen stimulation due to increased gut leakiness with age and/or intrinsic deterioration of fat body function59,75. The finding that Rapa repressed the number of Relish-positive nuclei and AMP expression even when bacterial growth was prevented by antibiotic treatment suggests that TORC1–S6K signaling regulates inflammaging via suppression of pathogen-independent sterile inflammation, which is in line with the findings in mammals24,85.

The endolysosomal system may directly affect the intracellular transport and degradation of immune regulators and receptors61,62. Here we discovered the importance of rPGRP-LC, a regulatory PGRP-LC isoform that helps resolve infection-induced IMD pathway activation via endosomes in young flies62, in age-associated inflammation. In middle-aged flies, rPGRP-LC might induce inflammation by an age-related decrease in internalization86,87,88. As a result, the rPGRP-LC–ligand complex, accumulated in the endolysosome, may not fully degrade and continues to activate the IMD pathway. Besides, similar to the endosomal sensing mechanisms of NOD2 (ref. 89), incomplete degradation of the rPGRP-LC–ligand complex may release its ligand, which is recognized by PGRP-LE, the intracellular receptor of the IMD pathway53. As Syx13 mediates endosome–lysosome fusion, overexpressing Syx13 could accelerate the internalization and degradation of the ligand and thereby suppress inflammaging. However, the source of PGRP-LC and rPGRP-LC ligands remains uncertain, especially when considering the role of PGRP-LC and S6K in inflammaging in the absence of bacterial infection. Thus, an alternative hypothesis suggests that rPGRP-LC accumulation in the cytosol may trigger other cytosolic stress mechanisms that could initiate inflammatory response, such as endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress90. Given that Rapa suppresses ER stress and its associated apoptosis in vitro91, the involvement of rPGRP-LC and TORC1–S6K signaling in ER stress-associated inflammaging needs further investigation.

Age-associated increases of RelB and NF-κB2 have been reported in human lymphocytes92. Our data reveal that Rapa suppressed the age-associated activation of noncanonical NF-κB pathway in mouse liver. Given that the noncanonical NF-κB pathway is triggered by limited stimuli, it points to its specialized role in the immune system72. Understanding how the noncanonical NF-κB signaling is regulated in aging, especially considering the role of rPGRP-LC in the Drosophila NF-κB-like IMD pathway activation, could shed light on the root causes and the consequences of inflammaging in mammals.

Another common feature of the aged immune system is immunosenescence56,57. Manipulation of TORC1–S6K–Syx13 signaling in the fly fat body alleviated pathogen clearance, suggesting suppression of immunosenescence. Inhibition of TORC1 in older adults elevates type 1 interferon signaling, which mediates anti-virus immune response and improves immune function93. Interestingly, these interferon-induced genes include IFITM3 (ref. 94) and Mx1 (ref. 95), which are associated with endocytic trafficking. Thus, the endolysosomal system might also play a role in improved immune function in humans in response to TORC1 inhibition. Immunosenescence has long been considered to drive inflammaging96. However, ameliorating inflammaging by repressing the key inflammatory regulator Relish in the fly fat body was sufficient to ameliorate immunosenescence, suggesting that inflammaging in the fly fat body acts upstream of immunosenescence. Immunosenescence in flies is often caused by the decreased phagocytic activity of hemocytes at advanced age59,97. Since the immune response in the fat body controls hemocyte activation98, one potential hypothesis would be that TORC1–S6K–Syx13 signaling in the fat body regulates hemocyte aging by inter-tissue communication, thereby ameliorating immunosenescence. In addition to the hemocyte-related cellular immune response, the fly fat body secrets AMPs into the hemolymph to kill invading pathogens; however, the functional capacity of this humoral immune response declines with aging99. Regulation of TORC1–S6K–Syx13 signaling in the fat body hence may be important for mediating pathogen-induced AMP expression in old flies.

In summary, our results establish that TORC1–S6K–Syx13 signaling regulates inflammaging in hepatic tissues via the endolysosomal system, thereby alleviating immunosenescence and enhancing longevity.

Methods

Fly stock and husbandry

All transgenic fly lines were backcrossed for at least six generations into the outbred wild-type strain, white Dahomey (wDah)100. For experiments, flies were maintained on 10% (w/v) brewer’s yeast, 5% (w/v) sucrose and 1.5% (w/v) agar food at 25 °C, 60% humidity, on a 12 h:12 h light:dark cycle. Rapa (LC Laboratories, #R-5000) was dissolved in ethanol and added to the food at a concentration of 200 µM. RU486 (Sigma, #M8046) was dissolved in ethanol and added to the food at a concentration of 100 µM to induce gene expression using the GeneSwitch system101. The corresponding control food contained only ethanol. Female flies were used in all experiments, with the exception of the experiments shown in Extended Data Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 9. Fly stocks are listed in Supplementary Table 6. Fly genotypes are indicated in the figure legend or in the panel body.

Mouse husbandry

The mouse Rapa study was performed in accordance with the recommendations and guidelines of the Federation of the European Laboratory Animal Science Association, with all protocols approved by the Landesamt für Natur, Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany (reference no. 81-02.04.2019.A313). Female F1 hybrid mice (C3B6F1) were generated in-house by crossing C3H/HeOuJ females with C57BL/6NCrl males (strain codes 626 and 027, respectively, Charles River Laboratories). Animals were housed in groups of five females in individually ventilated cages under specific-pathogen-free conditions with constant temperature (21 °C), 50–60% humidity and a 12 h:12 h light:dark cycle. For environmental enrichment, mice had constant access to nesting material and chew sticks. Rapa treatment was initiated at 6 months of age and was administrated continuously. Encapsulated Rapa was obtained from Rapa Holdings and was added to the food (ssniff R/M-low phytoestrogen, ssniff Spezialdiäten) at a concentration of 42 mg kg−1. Control food contained corresponding amounts of the encapsulation material Eudragit S100. Both Rapa and control food contained 3.2 ml kg−1 PEG-400. For tissue collection, mice were killed by cervical dislocation, and tissues were rapidly collected and snap-frozen using liquid nitrogen.

Generation of an UAS-Syx13 transgenic fly line

To generate the transgenic UAS-Syx13 fly line, full-length Syx13 sequence was polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified with primers (forward: TTTTTTCTCGAGCACCatgtccaaggccttgaaca and reverse: TTTTTTTCTAGAttaactgttcagtttggcaacga) using complementary DNA clone LD27581 (Drosophila Genomics Resource Center) as template. The PCR product was digested with XhoI and XbaI (NEB) and cloned into the pUAST-attB vector102. To increase expression efficiency, a CACC Kozak sequence was inserted directly before the ATG start codon. The phiC31-mediated integrase system102 was used to generate transgenic flies, using the attP40 insertion site103.

Lifespan, fecundity and starvation assays

For lifespan assays, parental flies were allowed to lay eggs for 18 h, embryos were collected in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and dispensed into bottles. Flies that enclosed within a 24 h time window were then transferred to fresh bottles where they were allowed to mate for 48 h. Subsequently, flies were anesthetized with CO2 and 20 female flies were sorted to vials. Flies were transferred to fresh food vials every 2–3 days and scored for death. For fecundity assays, flies were treated as described above for the lifespan assay, but only five female flies were used per vials. Eggs laid within 20 h were collected and counted twice a week in the first four weeks. For starvation assays, flies were reared and maintained as for lifespan assay. Ten-day-old flies were transferred to 1% agar and scored for deaths at least twice per day.

Peptide preparation for liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry analysis

Dissected fat bodies from 10-day-old and 50-day-old female flies (five fat bodies were pooled as a replicate, four replicates per group) or 50 mg mouse livers were lysed in 6 M guanidinium chloride, 2.5 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, 10 mM chloroacetamide and 100 mM Tris–HCl for 10 min at 95 °C. Lysates were further disrupted by using a Bioruptor plus (Diagenode). Samples were then diluted with 20 mM Tris and trypsin (Trypsin Gold, Promega, #V5280, 1:200 w/w) and digested overnight at 37 °C. Digestion was stopped by adding formic acid (FA) to a final concentration of 1%. Peptide cleaning was performed by using in-house C18-SD (Empore) StageTips104. Therefore, StageTips were washed with methanol and 40% acetonitrile (ACN)/0.1% FA and finally equilibrated with 0.1% FA. Digested peptides were loaded on the equilibrated StageTips. StageTips were washed twice with 0.1% FA, and peptides were eluted with 40% ACN/0.1% FA and then dried in a Speed-Vac (Eppendorf) at 45 °C.

TMT labeling and fractionation

Eluted peptides were reconstituted in 0.1 M triethylammonium bicarbonate. TMTpro 16plex (ThermoFisher, #A44522) labeling was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instruction with the following changes: 0.5 mg of TMT reagent was resuspended with 33 µl of anhydrous ACN. Seven microliters of TMT reagent in ACN was added to 9 µl of clean peptide in 0.1 M triethylammonium bicarbonate. The final ACN concentration was 43.75%, and the ratio of peptides to TMT reagent was 1:20. All 16 samples were labeled in one TMT batch. After 60 min of incubation the reaction was quenched with 2 µl of 5% hydroxylamine. Labeled peptides were pooled, dried, resuspended in 0.1% FA and desalted using StageTips. Samples were fractionated on a 1 mm × 150 mm, 130 Å, 1.7 µm ACQUITY UPLC Peptide CSH C18 Column (Waters, #186006935), using an Ultimate 3000 UHPLC (ThermoFisher). Peptides were separated at a flow of 30 µl min−1 with a 88 min segmented gradient from 1% to 50% buffer B for 85 min and from 50% to 95% buffer B for 3 min; buffer A was 5% ACN, 10 mM ammonium bicarbonate, buffer B was 80% ACN, 10 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Fractions were collected every 3 min, and fractions were pooled in two passes (1 + 17, 2 + 18 and so on) and dried in a Speed-Vac (Eppendorf).

Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry analysis and protein identification

Dried fractions were resuspended in 0.1% FA and separated on a 500 mm, 0.075 mm Acclaim PepMap 100 C18 HPLC column (ThermoFisher, #164942) and analyzed on a Orbitrap Lumos Tribrid mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher) equipped with a FAIMS device (ThermoFisher) that was operated in two compensation voltages, −50 V and −70 V. Synchronous precursor selection based MS3 was used for TMT reporter ion signal measurements. Peptides were separated by EASY-nLC1200 using a 90 min linear gradient from 6% to 31% buffer; buffer A was 0.1% FA, buffer B was 0.1% FA, 80% ACN. The analytical column was operated at 50 °C. Raw files corresponding to the mouse livers were split on the basis of the FAIMS compensation voltage using FreeStyle (ThermoFisher). Fly fat body proteomics data were analyzed using Proteome Discoverer (version 2.4.1.15); mouse liver proteomics data were analyzed using MaxQuant (version 1.6.17.0). Isotope purity correction factors, provided by the manufacturer, were included in the analysis.

Proteomics data analysis

Peptide intensity values were log2- and z-transformed. The results were rescaled by multiplying the z-intensity of each individual peptide with the global standard deviation of the log2-transformed data and adding back the global mean of the log2-transformed data. Only proteins that were detected in at least three out of the four replicates for each treatment were considered for downstream analyses. Missing values were imputed using the impute package (version 1.66.0) in R. Differential expression analysis was performed using the limma package (version 3.48.3) in R. For principal component analysis and plotting, batch effects from different dissection timepoints were removed from the normalized data using the limma package. The list of 5′TOP mRNA genes was obtained from Martin et al.105; the list of IMD-targeted AMPs was obtained from https://flybase.org/ using the Flybase ID: FBgg0001101; and the list of NF-κB-targeted genes was obtained from ref. 106.

Network propagation

High-confidence interactions of the STRING protein–protein association network database for Drosophila melanogaster or Mus musculus107 were extracted as background for later propagation (combined score >899). Network propagation was performed using the BioNetSmooth package (version 1.0.0) in R. log2 fold changes of comparisons were imported into the network and propagated with α = 0.5 for 26 iterations (for flies) or 25 iterations (for mice). Top and bottom 5% proteins that contain more than four protein–protein interactions were used for further analysis.

GO term enrichment

GO information was retrieved from org.Dm.eg.db package (version 3.13.0) or Uniprot-GOA database108 (version 2022-04-30) in R. The high-confidence interactions of STRING database (combined score >899) were set as background, and the results of network propagation were used for GO term enrichment analysis using Fisher tests with a minimal node size of five from ViSEAGO package (version 1.6.0) in R. Age-related GO terms were selected from the comparison of old versus young groups in the control treatment group of Lsp2GS>S6KCA dataset after network propagation. For Lsp2GS>S6KCA dataset, S6KCA-dependent Rapa-induced annotations were selected if the P value of Rapa versus control annotation is at least 100 times than the P value of S6KCA versus S6KCA + Rapa annotation (EtOHvsRapa.log10_pvalue − RUvsRURapa.log10_pvalue >2). S6KCA-independent Rapa-induced annotations were selected if the P value of Rapa versus control annotation is greater than 0.01 (EtOHvsRapa.log10_pvalue >2) and if the P value of Rapa versus control annotation is not 100 times than the P value of S6KCA versus S6KCA + Rapa annotation (EtOHvsRapa.log10_pvalue − RUvsRURapa.log10_pvalue ≤2). For mouse liver analysis, the biological processes significantly regulated (P < 0.05) as the same direction in all three datasets (hepatic proteome of 24m Rapa-treated mice, hepatic microarray of 25m Rapa-treated mice65, and hepatic microarray of 20m S6K1-deficient mice16) are plotted as shared up- or downregulated GO annotations after reducing redundancy via REVIGO (cutoff ‘0.7’, valueType ‘pvalue’, measure ‘SIMREL’). The significance score was calculated by the -log10_p-value with the sign of regulation direction (positive values for upregulated GOs and negative values for downregulated GOs).

Electron microscopy

Fat bodies were fixed in 4% formaldehyde (Science Services) and 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Merck) in 0.1 M Cacodylate buffer (AppliChem) for 48 h at 4 °C. After washing in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, tissues were treated with 2% osmiumtetroxid (Science Services) in 0.1 M Cacodylate buffer for 2 h. After dehydration of the sample with ascending ethanol concentrations followed by propylenoxid, samples were embedded in Epon (Sigma). Ultrathin sections (70 nm) were cut (EM-UC7, Leica Microsystems), collected onto mesh copper grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and contrasted with uranyl acetate (Plano GmbH) and lead citrate (Sigma). At least ten images per sample were acquired with a transmission electron microscope (JEM 2100 Plus, JEOL), a OneView 4K camera (Gatan) with DigitalMicrograph software at 80 kV at room temperature.

LysoTracker staining

Tissues were dissected in PBS and stained with LysoTracker Red DND-99 (ThermoFisher, #L7528, 1:2,000) and Hoechst 33342 (Enzo, #ENZ-52401, 0.5 ng µl−1). Samples were rinsed with PBS and mounted with VECTASHIELD Antifade Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories, #H-1000). Three images per sample were captured using a Leica TCS SP8 DLS confocal microscope with a 20× objective and 6× digital zoom-in. Images were processed by background subtraction, median filtering and spot quantification using Imaris 9 (Bitplane). Settings of the confocal microscope were kept consistent between images of an experiment. LysoTracker-positive puncta were defined as large, when the diameter was greater than 1.5 µm, which is the 75th percentile of the diameter of Rapa-induced LysoTracker-positive puncta.

Immunofluorescence

Tissues were dissected in PBS and fixed 30 min with 4% formaldehyde, methanol-free (ThermoFisher, #28908). Samples were washed in 0.3% Triton-X/PBS (PBST), blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/PBST for 1 h at room temperature, incubated in primary antibody overnight at 4 °C, and in secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-Relish (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, #21F3, 1:100), anti-Relish (RayBiotech, #RB-14-0004-200, 1:200) and anti-pH3 (Cell Signaling Technology, #9701, 1:200). The following secondary antibodies were used: Alexa Flour 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (ThermoFisher, #A11001, 1:1,000), Alexa Flour 633 goat anti-mice IgG (ThermoFisher, #A21050, 1:1,000), Alexa Flour 594 goat anti-rabbit IgG (ThermoFisher, #A11012, 1:1,000) and Alexa Flour 633 goat anti-rabbit IgG (ThermoFisher, #A21070, 1:1,000). Samples were mounted with VECTASHIELD Antifade Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, #H-1200). Three images per sample were captured using a Leica TCS SP8 DLS confocal microscope with 20× objective and 6× digital zoom. For Relish protein localization, images were processed by background subtraction and median filtering using Imaris 9 (Bitplane). The number of nuclei with high Relish fluorescence intensity was normalized by the total number of nuclei. Confocal settings were kept consistent between images of the same experiment.

Gut dysplasia assay

Guts were dissected in PBS and fixed 30 min with 4% formaldehyde, methanol-free (ThermoFisher, #28908). Samples were washed with PBS and mounted with VECTASHIELD Antifade Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, #H-1200). The R2 region of the gut was captured using a Leica TCS SP8 DLS confocal microscope with a 40× objective. Images were analyzed using Fiji109 (US National Institutes of Health). The percentage of dysplasia was calculated as the ratio between the length of multilayer nuclei region and the total length of the R2 region of the gut.

DQ–BSA/FITC–BSA pulse-chase assay

Fat bodies were dissected in Schneider’s Drosophila medium (Biowest, #L0207-500) and immediately pulsed for 10 min at room temperature with a mix of 100 µg ml−1 FITC–BSA (Sigma, #A9771) and 100 µg ml−1 DQ Red BSA (Life Technologies, #D12051) in Schneider’s Drosophila medium. Samples were rinsed with PBS and incubated for 2 h (chase) in Schneider’s Drosophila medium. Samples were rinsed with PBS and mounted with VECTASHIELD Antifade Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories, #H-1000). Three images per sample were captured using a Leica TCS SP8 DLS confocal microscope with a 20× objective and 6× digital zoom-in. Settings of the confocal microscope were kept consistent between images of an experiment. FITC channel images were processed by background subtraction, median filtering and spot quantification using Imaris 9 (Bitplane). FITC-positive puncta were defined as lysosomes and the mean fluorescence intensity of DQ-Red within these lysosomes was quantified as a readout of lysosomal degradation capacity.

Subcellular fractionation assay

Mouse livers were homogenized in ice-cold Nuclei EZ Prep lysis buffer (Sigma, #NUC-101) with 2 ml Dounce homogenizer, using both loose and tight pestles for 20 times. Extracts were incubated on ice for 30 min and centrifuged at 500g and 4 °C for 5 min. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fraction were collected separately and lysed and analyzed according to the immunoblotting assay. Histone H3 and GAPDH were used as nuclear and cytosolic marker proteins, respectively.

Immunoblotting

Tissues were homogenized and lysed in ice-cold RIPA buffer supplemented with cOmplete, Mini, EDTA-free, Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche, #11836170001) and PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor tablet (Roche, #049068370001) using a hand-held homogenizer. Extracts were centrifuged and protein concentrations were determined using Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (ThermoFisher, #23225). Extracts were mixed with 4× Laemmli loading buffer and boiled for 5 min at 95 °C. Ten micrograms (fly tissue and mouse tissue cell fractions) or 25 µg (mouse whole tissue lysis) of protein per lane on Any kD or 4–20% Criterion TGX stain-free precast gels (Bio-Rad) was transferred to Immobilon-FL polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore, #IPFL00010). Membranes were blocked by Intercept TBS Blocking Buffer (LI-COR, #927-60001) or 5% BSA for 1 h and probed with the following primary antibodies diluted in Intercept T20 TBS Antibody Diluent (LI-COR, #927-65001) or 5% BSA: anti-S6K3 (1:1,000), anti-pS6K T398 (Cell Signaling Technology, #9209, 1:1,000), anti-Relish (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, #21F3, 1:100), anti-tubulin (Sigma, #T9026,1:5,000), anti-puromycin (Sigma, #MABE343, 1:1,000), anti-Stx12 (Synaptic Systems, #110 132, 1:1,000), anti-RelA (Cell Signaling Technology, #8242, 1:1,000), anti-RelB (Cell Signaling Technology, #4922, 1:1,000), anti-NF-κB2 (Cell Signaling Technology, #4882, 1:1,000), anti-GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology, #2118, 1:5,000), anti-Histone H3 (abcam, #ab1791, 1:10,000). The following secondary antibodies were used: IRDye 800CW Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) (LI-COR, #926-32210, 1:15,000), IRDye 680RD Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) (LI-COR, #926-68071, 1:15,000), HRP-conjugate Goat anti-Rabbit IgG Antibody (Sigma, #12-348; 1:10,000) and HRP-conjugate Goat anti-Mouse IgG Antibody (Sigma, #12-349; 1:10,000). Total protein on the membrane was visualized as stain-free signal using ChemiDoc MP Imagers (Bio-Rad) and was used for normalizing protein expression levels. Signal was developed using Amersham ECL Select Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare). Immunoblotting images were captured using Odyssey Infrared Imaging system with application software V3.0.30 (LI-COR) or using ChemiDoc MP Imagers with Image Lab V6.1.0.07 (Bio-Rad) and were analyzed using Fiji109 (US National Institutes of Health).

RNA isolation and qRT–PCR

Total RNA was extracted from tissues using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, #74106). RNA concentration was measured using the Qubit RNA Broad Range Assay Kit (ThermoFisher, #Q10211). cDNA synthesis was performed using SuperScript VILO Master Mix (ThermoFisher, #11755-250) with 600 ng total RNA as input. Quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)–PCR was performed using SYBR Green Master Mix (ThermoFisher, #4367659) on a QuantStudio6 Flex Real-Time PCR System (ThermoFisher). Relative expression was determined using the ∆∆CT method and Rpl32 as normalization control. The following primers were used:

DptA-forward: CCACGAGATTGGACTGAATG

DptA-reverse: GGTGTAGGTGCTTCCCACTT

S6K-forward: ACTGGGCGCTCTCATGTTTG

S6K-reverse: TTGGCTTTCAGAATGGTCT

Rpl32-forward: ATATGCTAAGCTGTCGCACAAATGG

Rpl32-reverse: GATCCGTAACCGATGTTGGGCA

Triglyceride assay

Five whole flies were homogenized by 0.05% Tween-20 and incubated at 70 °C for 5 min. Extracts were centrifuged, the supernatant was mixed with prewarmed Infinity Triglycerides reagent (ThermoFisher, #TR22421) and incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. Protein content was determined by Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (ThermoFisher, #23225). Triglyceride levels were determined by plate reader at the absorbance of 540 nm using a triglyceride standard (Sigma, #17811-1AMP). Protein levels were used for normalization.

Puromycin incorporation assay

Fat bodies were dissected in PBS and immediately transferred to Schneider’s Drosophila medium with 5 µg ml−1 puromycin (Sigma, #P8833). For negative control, no puromycin was added in the Schneider’s Drosophila medium. Sample were incubated for 45 min with 400 rpm at 25 °C and then lysed according to the immunoblotting assay.

Antibiotic treatment

For antibiotic treatment, tetracycline and ampicillin were dissolved in water and added to the food in a concentration of 100 mg l−1 and 50 mg l−1, respectively. To test whether the treatment was efficient at removing bacteria, flies were dipped in 70% ethanol for 3 min and rinsed with sterile PBS. Individual flies were mashed in sterile PBS. Samples were plated on lysogeny broth (LB) plates and cultured at room temperature, and the number of bacterial colonies was scored at day 7.

Infection assays

For infection assays, flies were infected by pricking the thorax with a fine needle dipped in freshly cultured Ecc15 (OD600200). At 0 or 12 h post-infection (h.p.i.), flies were surface sterilized with 70% ethanol, rinsed with sterile PBS, and then three flies were homogenized in sterile PBS. Tenfold-series dilutions of fly homogenates were plated on LB plates as spots, cultured at room temperature, and the number of bacterial colonies was scored the next day. ‘0 h.p.i.’ represented the initial infectious dose and was not included in the statistical analysis. For ex vivo infection assay, fat bodies were dissected in sterile PBS and immediately incubated with PBS containing freshly cultured Ecc15 (final concentration OD6000.2) at room temperature for 1 h. For sham control, tissues were incubated with sterile PBS at room temperature for 1 h. Samples were then processed as described for immunofluorescence assay.

Statistics and reproducibility