Abstract

Although roads are widely seen as dispersal barriers, their genetic consequences for animals that experience large fluctuations in population density are poorly documented. We developed a spatially paired experimental design to assess the genetic impacts of roads on cyclic voles (Microtus arvalis) during a high-density phase in North-Western Spain. We compared genetic patterns from 15 paired plots bisected by three different barrier types, using linear mixed models and computing effect sizes to assess the importance of each type, and the influence of road features like width or the age of the infrastructure. Evidence of effects by roads on genetic diversity and differentiation were lacking. We speculate that the recurrent (each 3–5 generations) episodes of massive dispersal associated with population density peaks can homogenize populations and mitigate the possible genetic impact of landscape fragmentation by roads. This study highlights the importance of developing spatially replicated experimental designs that allow us to consider the large natural spatial variation in genetic parameters. More generally, these results contribute to our understanding of the not well explored effects of habitat fragmentation on dispersal in species showing “boom-bust” dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In today's globalized economy, the number of motor vehicles and the volume of transportation has reached unprecedented levels, increasing the ecological impact of the world’s human population during the last decades. Globally, roads currently cover more than a 20% of the earth’s land surface with large differences in occurrence, distribution and size of roadless areas among continents1. In Europe, for example, almost half of all continent is located within 1.5 km of the nearest transport infrastructure, with impacts that expand over most of the land and important reductions projected for birds and mammals2. Most empirical evidence suggests that this improvement of connectivity among human populations involves worsening of connectivity in wild animal populations3,4,5,6,7. In this sense, road networks can prevent animal movement, either through behavioral avoidance8,9 or mortality during crossing attempts10,11. These physical barriers may shape the dispersal behavior of species12, causing the isolation of populations into habitat fragments for many taxa13,14,15 with severe consequences for individuals and populations16,17,18. Research on this topic has shown that increasing habitat fragmentation and population isolation by roads can reduce locally the population size, the individual exchange among fragments and the gene flow, can have a significant impact on population genetic structure19,20 and often leads increased genetic drift and/or inbreeding, which can further reduce effective population sizes and genetic diversity over time. All this can have, in turn, potential implications for long-term population persistence14,21 due to the combined effects of inbreeding, genetic drift, and demographic and environmental stochasticity22,23, specially of those already small and inbred populations (but see Ref.24).

The barrier effect of roads varies largely with respect to road types, adjacent habitat quality, and traffic volume25,26,27,28. Specific road features, such as fences, median strips, drainage culverts, adjacent gravel and grassy verges, and structural passages beneath or above the paved surface influences road permeability for terrestrial species29. The severity of the barrier effect is often modulated by road width27,30 as the wider the barrier the higher the traffic intensity13,25, and the more reluctant or unable an individual will be to cross31,32. This effect is especially important in low-vagility species like small mammals or amphibians8,33. In addition, the time elapsed since road construction also affects the number of generations exposed to the putative barrier, influencing our ability to genetically measure the severity of the barrier effect34,35,36. However, species with high dispersal ability and abundance34,37,38, and large fluctuations in population size through time39 can mitigate the genetic effects of barriers, and our ability to detect them. Even so, studies on species that display large fluctuations in population size are particularly scarce40,41, limiting our understanding of the full impact of roads on animal populations.

Our ability to detect genetic effects from barriers depends also on the approach used. Studies conducted without some level of spatial replication and control groups make difficult to infer causal relationships since the results are subject to high variance caused by the interaction between species characteristics (e.g., population size, dispersal ability, habitat selection) and site-specific factors (e.g., habitat quality, road features, predation risk), which subsequently influences dispersal, relatedness and spatial genetic patterns26,42,43.

Here, we use the common vole Microtus arvalis (Pallas, 1779), a small-bodied rodent with short dispersal distances that reaches high local abundance42,44, as a model to test for the road effects on genetic diversity and structure in highly fragmented landscapes. The high colonization ability reported for the species in the last decades45 make it especially suitable to understand the dispersal mechanisms of small mammals over short time periods. Additionally, common vole populations reach high local abundances and may experience extreme fluctuations in density (1–2000 individuals per hectare)46 through 3–5 years population cycles with well-known phases (i.e., increase, peak, crash and low phases47. This cyclic variation in population size make this species particularly interesting to investigate the potential vulnerability to road barriers, compared to what has been described for other sympatric small mammals with more stable populations8,48,49. In a scenario of large fluctuations in population size, the time of lowest population size (low phase) should experience the highest levels of genetic drift50,51. As a result, demographic bottlenecks should have a strong effect on genetic variation, reducing diversity within and increasing differentiation among populations52,53,54. However, the high population size and gene flow during the peak phases could minimize the effects of drift and bottlenecks, although the system might take several generations to approach new equilibrium values41,55,56. In that context, investigating the effect of roads as barriers to gene flow, which can rapidly re-shuffle alleles among population demes, is particularly interesting in vole species, considering the short time lags between peak and low phases and its short generation time57.

In the present study, we used a spatially paired-plot design to test whether roads may influence genetic diversity and structure of populations in cyclic voles. We used study plots (2.5 × 3.0 km each) bisected by different types of paved roads (conventional 2-lane roads, 4-lane highways, or combined barriers) and spatially-matched plots bisected by an unpaved rural tracks to control for the impact of the road. We used paired t-tests, Linear Mixed-effect Models (LMMs) and estimated associated effect sizes to explore the potential barrier effect due to roads. We additionally tested if highways of different width and age (time since road construction) might influence any barrier effect. If the road is not an effective barrier, individual movements ending at the same side of the road should be equally frequent as those across the road, and therefore, genetic parameters within plots will remain unchanged. We further discuss other possible explanations to this pattern based on the characteristics of the study species, such as that the large population size reached during peak phases was marginally affected by genetic drift and there is no spatial variation in genetic structure independently of gene flow. The alternative scenario (road barrier effect) would generate—given enough generations—observable differences in the distribution of genetic variation within plots bisected by roads but not in plots without roads.

Results

A total of 1757 common voles were sampled at 1790 different sampling points across the 30 plots (Fig. 1). Of these, 1678 specimens genotyped at 9 microsatellite loci were kept for further analyses after removing samples unsuccessfully genotyped (n = 63) or resulting in the presence of full-sibs individuals in a plot (n = 16). A summary of allelic information across all plots is shown in Table 1. Since all locus showed no departure from Hardy Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) and no evidence for null alleles across all sites (Supplementary Tables S1, S2), all of them were kept for further analysis. The variables used to describe genetic diversity, structure and differentiation of common vole are shown in Table 2.

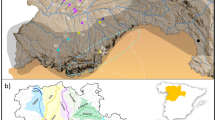

(a) Map of study area and sampling locations (plots). Plots are colored according to the features of the potential barrier type by which they are intersected; conventional 2-lane roads (R, Red), 4-lane highways (H, Blue), and combined barriers (CB, Purple), unpaved rural tracks (T, unfilled). Inset shows known distribution of common vole in Spain (10 × 10 km UTM-grids;126) where the red square delimits the study area. Plot codes correspond to Table A.1. Examples of trapping stations (10 traps per point) across control (b) and treatment (c) plots are shown for illustration purposes. Maps were generated using ESRI ArcGIS 10.3 Desktop platform (https://www.esri.com/en-us/home)58.

Genetic diversity

A summary of genetic diversity parameters of study plots is presented in Table 3. Genetic diversity was high at the 9 microsatellite loci. The mean number of alleles per locus ranged from seven (locus Mar063) to 28 (locus Mar012), expected heterozygosity (uHe) from 0.36 to 0.90 (Table 1), and the average number of alleles per study plot from 9.8 (R3) to 15 (CB1; Table 3) with similar levels of heterozygosity in all study plots (uHe: 0.77–0.84).

No diversity parameters showed strong differences between experimental and control plots (paired t-test p value > 0.1 in all cases, with negligible to small effect sizes; Table 4). Likewise, no effect of the barrier type on genetic diversity parameters was evident from the linear mixed models (LMMs hereafter) (effect size: f2 ≤ 0.15; Supplementary Tables S3, S4, Fig. 2). The relationship between Ho and Age of the barrier was positive and the effect size was large (Cohen’s f2 = 1.176) while the relationship with Ar was negative (Cohen’s f2 = 1.094), indicating greater differences in observed heterozygosity and lower differences in allelic richness between plots with highways and their controls over time. However, both effect sizes were found to have 95% confidence intervals (95% CI hereafter) that includes zero, suggesting the predictors may contribute very little to the relationship. We observed no substantial effect of Width on these parameters (Supplementary Table S3). Roads (R) showed lower differences between barrier sides than their controls in observed heterozygosity (HoDIF) while greater differences in allelic richness (ArDIF). Highways (H), however, presented lower differences in allelic richness (ArDIF) for experimental plots, all with large effect sizes. The strength of the relationship between Age and ArDIF was large and negative, and between Width and HoDIF was large and positive (Supplementary Table S4), indicating that differences in allelic richness between barrier sides among experimental and control plots diminished over time whereas differences in observed heterozygosity increased with increasing width, but as in the previous cases 95% CI included zero and was too wide to represent an acceptable level of uncertainty. We also discarded the existence of correlation between these differential estimators and sample size per plot (HoDIF; r = 0.202, uHeDIF; r = − 0.132, ArDIF; r = − 0.135).

Comparison of genetic diversity estimators (mean ± s.e) between treatments (filled dots: conventional 2-lane roads R, 4-lane highways H, and combined barriers CB) and their controls (empty dots). Ho: observed heterozygosity, uHe: unbiased expected heterozygosity, A: allelic richness. Means are computed as a global mean per plot (a) and as an absolute difference between barrier sides (b).

Genetic structure and differentiation

The Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) performed in each plot showed low values of genetic variance among individuals within the same side of the putative barrier (less than 8% in every plot; ΦIT = 0.003–0.077) and extremely small genetic variance between individuals from opposite sides of the putative barrier (less than 3% in every plot; ΦST = − 0.006–0.016; Supplementary Table S5). Most of the genetic variance (92.28–99.53%) was explained by differences within individuals (ΦIS = 0.001–0.075). The proportion of variance explained by the presence of the barrier was statistically significant in six out of the 30 (20%) study plots, but significant results were not associated with any particular type of barrier, nor were more prevalent in experimental than in control plots. Plots bisected by highways (H) and combined barriers (CB) tended to have variance ratio values between both plot sides (σBetween/σWithin) lower than their respective controls, showing a large effect for CB (Supplementary Table S6), whereas plots with conventional roads (R) showed greater values of variance ratio than their controls (Supplementary Fig. S1). However, there were no significant differences between experimental and control treatments (Table 4) and the mixed models showed a lack of significant effect of barrier Type. Barrier Age and barrier Width had again no significant effect on genetic variation, and effect sizes were small in all cases (Supplementary Table S6). The genetic differentiation tests (G-tests) were significant in the six plots with significant AMOVAs, but again not showing any particular pattern with respect to barrier type (data not shown).

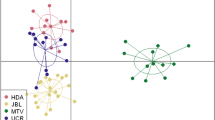

The Mantel’s correlation coefficient computed with the genetic distances (rGd, rDps, see methods section for further explanation and Table 2) showed lower rGd and rDps values for roads (R) and highways (H) compared to their controls. As expected, the Mantel’s r computed with the relatedness estimator (rLrm) displayed the opposite pattern (Fig. 3). Overall, paired t-test between experimental and control plots did not show significant differences in any Mantel’s statistic (Table 4, and Fig. 3), and effect sizes were all small. Variation of Mantel’s r did not depend on the barrier type based on LMMs, although the effect size was large for rGd in roads (R) and for rDps and rLrm in highways (H), showing lower values for rGd and rDps and greater values for rLrm in plots bisected by the infrastructure than in their respective controls (Supplementary Table S7). However, since the 95% CI included zero in both cases, the null hypothesis should not be rejected. Width or Age showed no statistically significant effect on genetic distance parameters.

Mean and standard error for Mantel r coefficients computed between the matrix of genetic distances (calculated as Gd, Dps and Lrm) and the binary model (designed to separate the same and opposite sides of the barrier), controlling for the effect of Euclidean distances (see text for further explanation). Means are computed for plots belonging to each type of putative barrier (filled dots; R, H, CB) and compared to their control plots (empty dots).

Averaged differentiation indices (Fst and G”st) for experimental and control plots are shown in Fig. 4. Plots crossed by combined barriers (CB) showed lower values of G”st compared to their controls, with large effect size (Supplementary Table S8). Conventional roads (R) showed higher differentiation (Fst and G”st) between barrier sides than their respective controls, but with only medium effect sizes. Nonetheless, paired t-tests did not reveal overall significant differences (Table 4) and neither Age nor Width appeared to influence these parameters (Supplementary Table S8).

Discussion

After accounting for the “natural” variation in genetic parameters occurring in our study system through control plots, we could not detect significant evidence to confirm that fragmentation by roads impacts the distribution of genetic variation. We detected a very small, almost null, deviation of genetic parameters from sites without barriers with respect to sites with putative barriers, suggesting either that subpopulations have recently been separated by roads and have not accumulated large differences, that the potential for voles to disperse overcomes the strength of the putative barrier to restrict gene flow, or that vole populations are marginally affected by genetic drift independently of gene flow.

Anthropogenic habitat fragmentation due to road construction is a ubiquitous feature that significantly alters modern landscape structure59,60. Generally, by dividing habitats into small fragments, roads act as barriers to gene flow of the isolated of populations. This can leads to adverse genetic effects, especially in species with low dispersal abilities61 or in species with low effective population size and thus more vulnerable to loss of genetic variation through drift62. A frequent limitation on these studies is that we cannot always possible to directly attribute the observed values of genetic parameters to anthropogenic changes without knowing the situation prior to fragmentation, because such values can result from natural subdivision of populations or may be due to other features present in the landscape, such as the abundance and distribution of habitats or the presence of elements in the landscape that influence individuals’ movement63. Unfortunately, we do not have samples available to represent conditions prior to road fragmentation for comparison, so we used a spatially paired design, using comparison between sites with and without paved roads to partially solve this problem64.

The genetic effects of fragmentation are expected to become more pronounced through time65, and not all methodological approaches are equally effective in detecting a recent barrier. Our studied barriers are relatively recent (time lag from 8 to 61 years-old) and therefore, our ability to detect genetic fragmentation with commonly used genetic indices, such as FST, could be compromised by a short time since fragmentation34,66 or by the analytical approach used. However, here we used multiple analytical methods to detect the presence of a linear barrier dividing populations. In addition to population-based approaches that generally requires a longer lag time to detect barriers, we used partial Mantel tests67 with individual‐based genetic and geographic distances, which can usually detect the signal of a new barrier within a shorter spatio-temporal scale34,36. Additionally, the study model is a short-lived species whose average lifespan is no longer than 4–5 months68 and a short-generation time (1 year69,70) so the expectation that genetic differences accumulate each generation since fragmentation makes it a suitable species for detecting barriers in the time frame considered71. Hence, the lack of evidence for population fragmentation by roads observed in the present work is less due to absence of evidence than evidence of absence. However, our findings do not agree with theoretical and empirical studies that suggest that landscape barriers can have rapid genetic effects that are detectable almost immediately or after a few generations72,73,74, but matches with expectations given the characteristics of the study species, such as its cyclical abundance, the large population size that it reaches in the peak phases and the severe population bottlenecks during the low phase of the cycle, the massive dispersal events associated with population peaks, or the short time lag between these two extremes (typically a few months).

One could argue that the lack of a barrier effect on genetic diversity and structure could be simply due to a large population size, since the amount of change in allele frequencies due to drift decreases as the effective population size increases51,62. Therefore, a lack of evidence of road barrier effect could be derived from a marginal effect of drift alone. However, vole population size does not remain high for a long time; the species is well known to suffer “boom-bust” dynamics75,76, with a peak every 3–5 generations in which population can fluctuate dramatically from 1000 voles/ha in high-density peaks to 10 voles/ha during population crashes, so it is unlikely that genetic diversity and structure would not be affected by bottleneck-associated drift during low phases.

It is more probable that substantial gene flow occurs across barriers, at least temporally, and that dispersal ability of the species outweighs any influence of the studied features. This is consistent with the lack of strong heterozygote deficiencies, which would be expected if there were an increase in mating events between relatives due to a dispersal decline. Dispersal would increase the geographic scale of genetic structuring, as previously suggested for other cyclic species like Siberian lemmings77 and would explain the apparent lack of local genetic structure attributable to roads, matching with previous studies performed on the same species78.The analyses of genetic variation in the 30 study sites also revealed an apparent lack of local genetic structure attributable to roads, and the differences in the distribution of variance within and between barrier sides do not seem currently affected by road type. Altogether, these results point to compensating mechanisms, probably related to gene flow and frequent dispersal, that could outweigh the overall impact of roads in this species.

The question remains as to whether the lack of barrier effect observed is due to permanent high dispersal rates over time (i.e. high gene flow across the barrier remains constant from one generation to the next) or if the barrier effect varies through time following changes in Ne. Unfortunately, we do not have temporally replicated data to test this, something that needs to be addressed. However, the well-known cases of barrier effect of roads in similar species and the cyclical nature of the common vole suggests barrier effect varies through time. Roads with similar characteristics to those of this study have been proven effective in reducing the gene flow on a local scale of other mammals similar in size and vagility to common voles, but lacking strong abundance cycles8. In cyclic voles, data on dispersal distances are scarce, but the most frequent seem to be short-distance dispersal events carried out mainly by females79, which can reach 50–160 m in the case of short-range natal dispersal, but occasionally up to 400 m in a few days44. This can lead to significant genetic differentiation even at spatial scales of a few hundred meters80. However, common voles are also capable of dispersing on the order of a few kilometers79 being these occasional long-distance dispersal events more balanced between genders80. The species also shows conspicuous and recurrent episodes of massive dispersal41,45 that may genetically homogenize populations. These episodes, although far from clear, are widely understood in the cyclic rodent literature as presaturation dispersal81,82,83 and occur under positive growth rates when the patch’s carrying capacity has not yet been reached81. Such dispersal events, together with the high effective population size reached during peak phases, may help us to explain the high genetic diversity that common vole maintains in the region. High levels of genetic diversity are well documented for other cyclic small mammals56,84, and suggest that population dynamics and dispersal movements play a key role in configuring the genetic diversity of open populations85.

In conclusion, our study points out a scenario in which, although there may be periods of relative isolation by roads for a few generations, they regularly alternate with a relatively high panmictic-density phase in which mixing and accumulation of genetic material across barriers occurs, probably due to the cyclic nature of the common vole. These repetitive (cyclic) pulses of gene flow might homogenize populations and erase the possible differences that may have accumulated during the short time elapsed between the “boom” phases. Nevertheless, we cannot conclusively discard that our findings can be explained by other factors independently of gene flow, such as for example a low drift effect and/or the high effective population size during the peak phases. Further research on populations that have been in a low population phase for some time, testing for potential effects of roads over short time scales, would be particularly valuable in that context. We also urge caution in the interpretation of these results to avoid over-emphasizing the low ecological significance of these local barrier effects on populations without larger sample sizes and better temporal sampling coverage, since we detected large effect sizes and trends attributable to roads but which we could not confirm with certainty. A larger number of replicates would give the design the ability to detect smaller differences (higher statistical power) than in the present study, thus reducing the risk for Type-II errors.

Last but not least, the present work underlines the importance of having a robust experimental design and sufficient spatial replication in studies of barrier effects, given the natural spatial variation in genetic parameters. For example, the proportion of genetic variance explained by the putative barrier was statistically significant in the 20% of our study plots, but significant results were not associated with any particular type of barrier, nor were more prevalent in experimental than control plots. This emphasizes the fact that studying the relationship between landscape fragmentation and genetic diversity/structure in single sites can be problematic because the observed genetic parameters are often site-specific and a basis for comparison is lacking, and therefore single-case studies will not allow firm conclusions.

Methods

Study area, experimental design and animal collection

We conducted the study in the region of Castilla y León (NW Spain), which includes the Duero River basin, a central agricultural plain (ca. 3.7 million ha; 37.8% of the total area of Castilla y León86) characterized by a landscape generally flat with few trees and subject to a moderate-to-high agricultural exploitation87. The region combines cities and rural areas, with a well-developed road network that has been expanded and upgraded in recent decades and that includes a wide variety of road types (Fig. 1).

We conducted a field experiment with a matched pairs design using 15 pairs of rectangular study plots (2.5 × 3.0 km, Fig. 1). Each pair consisted of one (experimental) plot longitudinally bisected by a paved transport infrastructure (hereafter: road), leaving approximately 2.5 × 1.5 km at each side of the putative barrier (hereafter: barrier sides), and another (control) plot that was bisected by an unpaved rural track (T). Rural tracks of 4–6 m wide were used as positive controls of the potential barrier effect of major roads since they were assumed to have much less influence on species movement28,88 and consequently, on gene flow.

Pairs of experimental and control plots were chosen based on close proximity, with similar environmental and habitat conditions within the agrarian landscape. However, it was not possible to place pairs randomly across the landscape due to the need of: (i) finding plots bisected by a single road, with no other nearby infrastructures, (ii) having dirt tracks that crossed control plots in similar way to roads in experimental plots, and (iii) ease of simultaneous access to multiple sites during mammal trapping. We also avoided sites with any obvious signs of disturbance such as burning, human settlements and other constructions, that could confound analysis of the effects of roads on genetic differentiation. Therefore, we located sampling sites on flat terrain and avoiding any field with streams that were parallel to the road, thus avoiding possible additional barriers to common vole gene flow89,90.

The two plots in each pair (treatment and its control) were spaced 2–4 km apart, and each set of pairs was separated by 6–26 km to promote independence. We considered three treatments (types of road) in the experimental design, each one having intrinsic features (Supplementary Table S9): conventional 2 lane-roads (R) that represented the oldest and narrowest paved transport infrastructures in the region, 4-lane highways (H) with intermediate ages and sizes, and combined barriers (CB), where R and H run parallel and proximate (Fig. 1), that represented the widest and most recent infrastructures. Specific road features like width (considered as the distance between the outermost edges—including paved lanes plus gravel shoulders/drainage systems—of the infrastructure) were obtained using Google Earth and data from the Spanish Ministry of Development, whereas the historical imagery of Google Earth and the stereoscopic aerial images available from the American Flight B series (AMS 1956–1957) to present, allowed us to calculate the year of construction (data provided by Confederación Hidrográfica del Duero).

Voles were live-trapped in 30 study plots from late April to the end of July 2017, the year following a population peak phase in the region91. We established Sherman traps (H.B. Sherman Traps Inc. Florida, USA) in 26–96 capture points per study plot, with 10 traps per point, deployed through the entire plot (260–960 traps per study plot). We tried to ensure that trap locations encompassed the diversity of habitats (e.g., crop fields, fallows, field margins, boundaries of roads and rural tracks, ditches), but > 500 m from plot boundaries to reduce potential edge effects92. Traps were open for 24 h, or until captures reached a minimum of at least 20 individuals per infrastructure side, which usually took no more than 48 h. However, we were not always able to reach the desired number of 20 samples per plot side (see Table 3). From each individual, we took 2 mm tissue biopsies from the ear and preserved them in 96% ethanol. All animals were released back to their exact point of capture. Precise locations of each trapping site were quantified using a hand-held GPS (± 4 m error).

All procedures were approved by the University of Castilla-La Mancha's Committee on Ethics and Animal Experimentation (CEEA, UCLM, Spain; reference number PR20170201), were within the guidelines of the European and Spanish and policy for animal protection and experimentation and in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines for how to report animal experiments.

DNA extraction and microsatellite genotyping

Total genomic DNA was extracted from tissue samples using a standard ammonium acetate protocol93, and diluted to a working concentration of 25 ng/μL. 9 microsatellite loci isolated in common vole94,95 were amplified in a total volume of 10 μL containing 1 × QIAGEN Multiplex PCR Master Mix, 0.2 μM of each primer (forward and reverse) and 20–50 ng of DNA. The 9 primer pairs were divided into two multiplexes using four dyes (FAM, PET, NED, VIC): Ma09, Mar012, Ma54, Ma66, (Multiplex 1); MM6, Mar063, Mar003, Mar016, Mar102 (Multiplex 2). Electrophoresis of PCR products was performed by Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Unidad de Genómica, Spain (https://www.ucm.es/gyp/genomica). Electropherograms were scored using Geneious 10.2.3 (https://www.geneious.com) and approximately 10% of all genotypes were re-amplified and re-scored to estimate the genotyping error rate.

Prior to statistical analysis, microsatellite error rate was calculated to check for allelic dropout and false alleles using Pedant v1.096. Hardy Weinberg equilibrium and Linkage disequilibrium were checked across all loci in the R package ‘pegas’97. We checked for the presence of null alleles following Brookfield98 implemented in the R package ‘PopGenReport v3.0.4′99. We used COLONY 2.0100 to identify and discard full and half siblings at the same sampling point from the dataset, which may indicate the presence of litters and bias the allele frequencies at a given spatial location. COLONY was run under a non-restrictive criterion considering a polygynandrous scenario (both male and female potentially polygamous). Analyses were performed according with the full-likelihood method with high precision, three runs of medium length and without priors. Since COLONY provides the uncertainty estimates (in probabilities) of a particular substructure, we assess, for each of our sampling points, the probability that the captured individuals share both (full siblings) or one parent (half-siblings) using a threshold of substructure probability p ≥ 0.95. Then, we randomly discard all but one full sibling from each sampling location. Siblings sampled at different sampling points were retained for analysis.

Genetic diversity

We estimated genetic diversity through ‘diveRsity’ v1.1.9101 R package. We first calculated observed (Ho) and expected (He) heterozygosity, unbiased expected heterozygosity (uHe), allelic richness (Ar) and inbreeding coefficient (FIS). We used ‘GENHET’ v3.1102 R package to calculate five measures of genetic diversity at the individual level, as described in Coulon102: the proportion of heterozygous loci (PHt), standardized heterozygosity based on the mean observed heterozygosity (Hs_obs), standardized heterozygosity based on the mean expected heterozygosity (Hs_exp103), internal relatedness (IR104), and homozygosity by locus (HL105). All metrics of genetic diversity were calculated (i) as a mean value per plot, using all samples collected in each plot, and (ii) as a mean value in each side of the putative barrier within each plot (arbitrarily coded as A and B). We then computed an absolute difference across the barrier to obtain a single value per plot (HoDIF, HeDIF, uHeDIF, ArDIF, FisDIF, PHtDIF, Hs_obsDIF, Hs_expDIF, IRDIF, HLDIF). To verify that the observed values for these estimates (differences in diversity) were not just a consequence of sample size, we computed a Pearson’s correlation coefficient between our diversity parameters and the sample size per plot. In a possible scenario of subtle isolation due to roads, we would expect that although there were no differences in the overall diversity between an experimental plot and its control, we found differences in the way that diversity was distributed in relation to the position of the barrier (and absence of differences among sides in the control plot).

Genetic structure and differentiation

Based on AMOVA and Phi-statistics, genetic variation between the two roadsides was estimated for all plots using three hierarchical levels: roadside, sampling site (plot) and individual. For the assessment of potential barriers, individuals where assigned to their respective roadside. AMOVA was performed with 999 permutations to assess significance in ‘poppr’106 R package. Regardless of the outcome of the AMOVA tests computed in each plot, our aim was to identify an overall difference in the variance explained by the putative barrier between the experimental plots and their paired controls. We then computed the ratio of the genetic variance between different sides of the barrier to the variance on the same side of the barrier (σbw = σBetween/σWithin). This parameter was used as a response variable in subsequent analysis (see below), which was expected to be greater in the presence of a barrier effect. GENALEX v6.5107 was also used to assess pairwise genetic differentiation (FST) between groups of individuals at each side of the putative barrier within each plot, therefore testing genetic structuring by the barrier, and statistical significance based on 999 permutations. Recent analyses suggest that this standard measure of differentiation may be poorly suited for data sets in which allelic diversity is high108,109,110. Given the high variability of the markers used here, we also computed other measures of differentiation: GST111, G”ST112, G’STH108 and D109 following the recommendations and formulae of Meirmans and Hedrick110.

Because some authors113,114 have suggested that metrics based on genetic differentiation among groups of individuals may have low power to detect isolation, we also computed individual-based genetic distances within each plot. Pairwise individual genetic distances were estimated using the proportion of shared alleles (Dps113) and codominant genotypic distance (Gd115). For Dps, we subtracted values from one to obtain a distance measure and make it comparable with Gd. We additionally computed three relatedness indicators per plot: Qgm116, Ri117 and Lrm118 that measure genetic similarity in terms of probabilities of identity-by-descent including the overall population allele frequencies as a parameter (in our case, the average allele frequencies calculated over the 30 plots). We multiplied Lrm by two to make it comparable with the other relatedness estimators, but we did not subtract values in this case since negative values are informative for these metrics. Gd and relatedness estimators were calculated in GENALEX and Dps in “adegenet” v2.1.1119 R package.

As we were aware of the potential spatial autocorrelation of individuals in our plots and that spatial dependence can interfere with our ability to make statistical inferences120, we also calculated pairwise Euclidean geographic distances among individuals. We then used genetic, geographic, and a third “barrier” matrix to compute a partial Mantel test per plot. The elements of our barrier matrix were binary (i.e., 0 between samples from the same side of the putative barrier, 1 between samples separated by the putative barrier). Under the null hypothesis (H0), one would expect that the genetic distances among samples are unrelated to the corresponding treatment distances (while controlling for corresponding geographic distances). Under the alternative hypothesis (H1) we expected to find significant correlation between genetic and treatment distances. Therefore, Mantel r coefficient was expected to be greater in the test carried out with the experimental plots than with the control plots.

Statistical analysis

Due to the large number of metrics employed in the study, we retained only those which provided non-redundant information based on a correlation matrix with a Pearson’s coefficient threshold < 0.80121 to be used as response variables. These included Fst and G”st as differentiation metrics, σbw as a measure of genetic variation, Ho, uHe, Ar and their homologous computations of differences between plot sides (HoDIF, uHeDIF, ArDIF) as genetic diversity estimators, and partial Mantel r (rGd, rDps, rLrm). A detailed explanation of each estimator is given in Table 2.

First, we performed paired t-tests between experimental and their respective controls for each group of metrics to assess a Treatment effect. Then, we constructed Linear Mixed-effect Models (LMMs) to analyze variation in genetic metrics according to the type of putative barriers, including barrier Type as a fixed factor with the three treatments (R, H, CB) and the control (T) as factor levels. Because of the nature of our sampling design, each experimental plot and its paired control were coded with the same identification number, which was included in the models as a random factor (GroupID) to make appropriate paired comparisons. We also conducted separate analyses to examine the effect of road Width and Age on genetic metrics. We restricted this analysis to highways, as they had larger contrast relative to the control plots than roads, which had all the same age, and lacked infrastructures with different age and width (CB), which potentially complicates interpretation. Therefore, we performed simple linear regressions after verifying that there was no significant correlation between Age and Width of the barrier for this data subset (r = 0.043, p = 0.895). Since this is a matched pair study we used the differences in genetic parameters between each experimental plot and its paired control plot as response variable in the linear regressions.

Due to the low sample size in both sets of models we cannot rule out the possibility of insufficient statistical power. Therefore, we estimated the effect size by computing Hedges’s g122, corrected for small sample sizes, with ‘bootES’123 R package, and used the threshold provided in Ref.124 to assess the magnitude of the effect in paired t-tests and LMMs, i.e. |g|< 0.2: negligible; 0.2 ≤|g|≤ 0.5: small; 0.5 ≤|g|≤ 0.8: medium; |g|> 0.8: large. We bootstrapped 999 times on effect sizes to get the 95% confidence intervals, which can inform inferences about the replicability and generalizability of the results. In the same way, we computed Cohen’s f2 for simple regression models as described in Ref.125 for the highways (H) subset: 0.02 ≤|f2|< 0.15: small; 0.15 ≤|f2|< 0.35: medium; |f2|≥ 0.35: large.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ibisch, P. L. et al. A global map of roadless areas and their conservation status. Science 354, 1423–1427 (2016).

Torres, A., Jaeger, J. A. G. & Alonso, J. C. Assessing large-scale wildlife responses to human infrastructure development. PNAS 113, 8472–8477 (2016).

Bennett, V. J. Effects of road density and pattern on the conservation of species and biodiversity. Curr. Landsc. Ecol. Rep. 2, 1–11 (2017).

Coffin, A. W. From roadkill to road ecology: a review of the ecological effects of roads. J. Transp. Geogr. 15, 396–406 (2007).

Fahrig, L. & Rytwinski, T. Effects of roads on animal abundance: an empirical review and synthesis. Ecol. Soc. 14, 21 (2009).

Forman, R. T. & Alexander, L. E. Roads and their major ecological effects. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 29, 207–231 (1998).

Trombulak, S. C. & Frissell, C. A. Review of ecological effects of roads on terrestrial and aquatic communities. Conserv. Biol. 14, 18–30 (2000).

Ascensão, F. et al. Disentangle the causes of the road barrier effect in small mammals through genetic patterns. PLoS ONE 11, e0151500 (2016).

Dyer, S. J., O’Neill, J. P., Wasel, S. M. & Boutin, S. Quantifying barrier effects of roads and seismic lines on movements of female woodland caribou in northeastern Alberta. Can. J. Zool. 80, 839–845 (2002).

Glista, D. J., DeVault, T. L. & DeWoody, J. A. A review of mitigation measures for reducing wildlife mortality on roadways. Landsc. Urban Plan. 91, 1–7 (2009).

Taylor, B. D. & Goldingay, R. L. Roads and wildlife: impacts, mitigation and implications for wildlife management in Australia. Wildl. Res. 37, 320–331 (2010).

Tigas, L. A., Van Vuren, D. H. & Sauvajot, R. M. Behavioral responses of bobcats and coyotes to habitat fragmentation and corridors in an urban environment. Biol. Conserv. 108, 299–306 (2002).

Herrmann, H.-W., Pozarowski, K. M., Ochoa, A. & Schuett, G. W. An interstate highway affects gene flow in a top reptilian predator (Crotalus atrox) of the Sonoran Desert. Conserv. Genet. 18, 911–924 (2017).

Holderegger, R. & Di Giulio, M. The genetic effects of roads: a review of empirical evidence. Basic Appl. Ecol. 11, 522–531 (2010).

Keller, L. F. & Waller, D. M. Inbreeding effects in wild populations. Trends Ecol. Evol. 17, 230–241 (2002).

Benítez-López, A., Alkemade, R. & Verweij, P. A. The impacts of roads and other infrastructure on mammal and bird populations: a meta-analysis. Biol. Conserv. 143, 1307–1316 (2010).

Kerley, L. L. et al. Effects of roads and human disturbance on Amur tigers. Conserv. Biol. 16, 97–108 (2002).

Roedenbeck, I. A. & Voser, P. Effects of roads on spatial distribution, abundance and mortality of brown hare (Lepus europaeus) in Switzerland. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 54, 425–437 (2008).

Clark, R. W., Brown, W. S., Stechert, R. & Zamudio, K. R. Roads, interrupted dispersal, and genetic diversity in timber Rattlesnakes. Conserv. Biol. 24, 1059–1069 (2010).

Niko, B. & Waits, L. P. Molecular road ecology: exploring the potential of genetics for investigating transportation impacts on wildlife. Mol. Ecol. 18, 4151–4164 (2009).

Frankham, R., Briscoe, D. A. & Ballou, J. D. Introduction to Conservation Genetics (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Amos, W. & Balmford, A. When does conservation genetics matter?. Heredity 87, 257–265 (2001).

Frankham, R. Genetics and extinction. Biol. Cons. 126, 131–140 (2005).

Teixeira, J. C. & Huber, C. D. The inflated significance of neutral genetic diversity in conservation genetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 118, e2015096118 (2021).

Keller, I. & Largiadèr, C. R. Recent Habitat fragmentation caused by major roads leads to reduction of gene flow and loss of genetic variability in ground beetles. Proc. Biol. Sci. 270, 417–423 (2003).

Noël, S., Ouellet, M., Galois, P. & Lapointe, F.-J. Impact of urban fragmentation on the genetic structure of the eastern red-backed salamander. Conserv. Genet. 8, 599–606 (2007).

Marsh, D. M. et al. Effects of roads on patterns of genetic differentiation in red-backed salamanders, Plethodon cinereus. Conserv. Genet. 9, 603–613 (2008).

Brehme, C. S., Tracey, J. A., Mcclenaghan, L. R. & Fisher, R. N. Permeability of roads to movement of scrubland lizards and small mammals. Conserv. Biol. 27, 710–720 (2013).

Ford, A. T. & Clevenger, A. P. Factors affecting the permeability of road mitigation measures to the movement of small mammals. Can. J. Zool. 97, 379–384 (2018).

Claireau, F. et al. Major roads have important negative effects on insectivorous bat activity. Biol. Conserv. 235, 53–62 (2019).

Jacobson, S. L., Bliss-Ketchum, L. L., Rivera, C. E. & Smith, W. P. A behavior-based framework for assessing barrier effects to wildlife from vehicle traffic volume. Ecosphere 7, e01345 (2016).

Assis, J. C., Giacomini, H. C. & Ribeiro, M. C. Road permeability index: evaluating the heterogeneous permeability of roads for wildlife crossing. Ecol. Ind. 99, 365–374 (2019).

Lesbarrères, D., Primmer, C. R., Lodé, T. & Merilä, J. The effects of 20 years of highway presence on the genetic structure of Rana dalmatina populations. Écoscience 13, 531–538 (2006).

Landguth, E. L. et al. Quantifying the lag time to detect barriers in landscape genetics: quantifying the lag time to detect barriers in landscape genetics. Mol. Ecol. 19, 4179–4191 (2010).

Epps, C. W. & Keyghobadi, N. Landscape genetics in a changing world: disentangling historical and contemporary influences and inferring change. Mol. Ecol. 24, 6021–6040 (2015).

Blair, C. et al. A simulation-based evaluation of methods for inferring linear barriers to gene flow. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 12, 822–833 (2012).

Mona, S., Ray, N., Arenas, M. & Excoffier, L. Genetic consequences of habitat fragmentation during a range expansion. Heredity 112, 291–299 (2014).

Weyer, J., Jørgensen, D., Schmitt, T., Maxwell, T. J. & Anderson, C. D. Lack of detectable genetic differentiation between den populations of the Prairie Rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis) in a fragmented landscape. Can. J. Zool. 92, 837–846 (2014).

Frankham, R. Relationship of genetic variation to population size in wildlife. Conserv. Biol. 10, 1500–1508 (1996).

Ehrich, D. & Jorde, P. E. High genetic variability despite high-amplitude population cycles in lemmings. J. Mammal. 86, 380–385 (2005).

Gauffre, B. et al. Short-term variations in gene flow related to cyclic density fluctuations in the common vole. Mol. Ecol. 23, 3214–3225 (2014).

Schweizer, M., Excoffier, L. & Heckel, G. Fine-scale genetic structure and dispersal in the common vole (Microtus arvalis). Mol. Ecol. 16, 2463–2473 (2007).

Keane, B., Ross, S., Crist, T. O. & Solomon, N. G. Fine-scale spatial patterns of genetic relatedness among resident adult prairie voles. J. Mammal. 96, 1194–1202 (2015).

Boyce, C. C. K. & Boyce, J. L. Population biology of Microtus arvalis. II. Natal and breeding dispersal of females. J. Anim. Ecol. 57, 723–736 (1988).

Luque-Larena, J. J. et al. Recent large-scale range expansion and outbreaks of the common vole (Microtus arvalis) in NW Spain. Basic Appl. Ecol. 14, 432–441 (2013).

Salamolard, M., Butet, A., Leroux, A. & Bretagnolle, V. Responses of an avian predator to variations in prey density at a temperate latitude. Ecology 81, 2428–2441 (2000).

Krebs, C. J. & Myers, J. H. Population cycles in small mammals. In Advances in Ecological Research Vol. 8 (ed. MacFadyen, A.) 267–399 (Academic Press, 1974).

Gerlach, G. & Musolf, K. Fragmentation of landscape as a cause for genetic subdivision in bank voles. Conserv. Biol. 14, 1066–1074 (2000).

Rico, A., Kindlmann, P. & Sedláček, F. Can the barrier effect of highways cause genetic subdivision in small mammals?. Acta Theriol. 54, 297–310 (2009).

Nei, M., Maruyama, T. & Chakraborty, R. The bottleneck effect and genetic variability in populations. Evolution 29, 1–10 (1975).

Motro, U. & Thomson, G. On heterozygosity and the effective size of populations subject to size changes. Evolution 36, 1059–1066 (1982).

Kirkpatrick, M. & Jarne, P. The effects of a bottleneck on inbreeding depression and the genetic load. Am. Nat. 155, 154–167 (2000).

Xenikoudakis, G. et al. Consequences of a demographic bottleneck on genetic structure and variation in the Scandinavian brown bear. Mol. Ecol. 24, 3441–3454 (2015).

Parra, G. J. et al. Low genetic diversity, limited gene flow and widespread genetic bottleneck effects in a threatened dolphin species, the Australian humpback dolphin. Biol. Conserv. 220, 192–200 (2018).

Berthier, K., Charbonnel, N., Galan, M., Chaval, Y. & Cosson, J.-F. Migration and recovery of the genetic diversity during the increasing density phase in cyclic vole populations. Mol. Ecol. 15, 2665–2676 (2006).

Norén, K. & Angerbjörn, A. Genetic perspectives on northern population cycles: bridging the gap between theory and empirical studies: GENETIC structure in cyclic populations. Biol. Rev. 89, 493–510 (2014).

Jangjoo, M., Matter, S. F., Roland, J. & Keyghobadi, N. Demographic fluctuations lead to rapid and cyclic shifts in genetic structure among populations of an alpine butterfly, Parnassius smintheus. J. Evol. Biol. 33, 668–681 (2020).

ESRI. ArcGIS desktop: release 10.3 Environmental Systems Research Institute, Redlands, CA (2015).

Saunders, S. C., Mislivets, M. R., Chen, J. & Cleland, D. T. Effects of roads on landscape structure within nested ecological units of the Northern Great Lakes Region, USA. Biol. Conserv. 103, 209–225 (2002).

Fahrig, L. Effects of habitat fragmentation on biodiversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 34, 487–515 (2003).

Schlaepfer, D. R., Braschler, B., Rusterholz, H.-P. & Baur, B. Genetic effects of anthropogenic habitat fragmentation on remnant animal and plant populations: a meta-analysis. Ecosphere 9, e02488 (2018).

Charlesworth, B. Effective population size and patterns of molecular evolution and variation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 195–205 (2009).

Compton, B. W., McGarigal, K., Cushman, S. A. & Gamble, L. R. A resistant-Kernel model of connectivity for amphibians that breed in vernal pools. Conserv. Biol. 21, 788–799 (2007).

Balkenhol, N., Cushman, S., Storfer, A. & Waits, L. Landscape Genetics: Concepts, Methods, Applications (Wiley, 2015).

Aguilar, R., Quesada, M., Ashworth, L., Herrerias-Diego, Y. & Lobo, J. Genetic consequences of habitat fragmentation in plant populations: susceptible signals in plant traits and methodological approaches. Mol. Ecol. 17, 5177–5188 (2008).

Lloyd, M. W., Campbell, L. & Neel, M. C. The Power to Detect Recent Fragmentation Events Using Genetic Differentiation Methods. PLoS ONE 8, e63981 (2013).

Smouse, P. E., Long, J. C. & Sokal, R. R. Multiple regression and correlation extensions of the mantel test of matrix correspondence. Syst. Zool. 35, 627–632 (1986).

Nowak, R. M. Walker’s Mammals of the World (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999).

García, J. T. et al. A complex scenario of glacial survival in Mediterranean and continental refugia of a temperate continental vole species (Microtus arvalis) in Europe. J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 58, 459–474 (2020).

Martínková, N. et al. Divergent evolutionary processes associated with colonization of offshore islands. Mol. Ecol. 22, 5205–5220 (2013).

Keyghobadi, N. K. The genetic implications of habitat fragmentation for animals. Can. J. Zool. 85(10), 1049–1064 (2007).

Vandergast, A. G., Bohonak, A. J., Weissman, D. B. & Fisher, R. N. Understanding the genetic effects of recent habitat fragmentation in the context of evolutionary history: phylogeography and landscape genetics of a southern California endemic Jerusalem cricket (Orthoptera: Stenopelmatidae: Stenopelmatus). Mol. Ecol. 16, 977–992 (2007).

Zellmer, A. J. & Knowles, L. L. Disentangling the effects of historic vs. contemporary landscape structure on population genetic divergence. Mol. Ecol. 18, 3593–3602 (2009).

Delaney, K. S., Riley, S. P. D. & Fisher, R. N. A rapid, strong, and convergent genetic response to urban habitat fragmentation in four divergent and widespread vertebrates. PLoS ONE 5, e12767 (2010).

Tkadlec, E. & Stenseth, N. C. A new geographical gradient in vole population dynamics. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 268, 1547–1552 (2001).

Lambin, X., Bretagnolle, V. & Yoccoz, N. G. Vole population cycles in northern and southern Europe: Is there a need for different explanations for single pattern?. J. Anim. Ecol. 75, 340–349 (2006).

Ehrich, D. & Stenseth, N. C. Genetic structure of Siberian lemmings (Lemmus sibiricus) in a continuous habitat: large patches rather than isolation by distance. Heredity 86, 716–730 (2001).

Gauffre, B., Estoup, A., Bretagnolle, V. & Cosson, J. F. Spatial genetic structure of a small rodent in a heterogeneous landscape. Mol. Ecol. 17, 4619–4629 (2008).

Galliard, J.-F.L., Rémy, A., Ims, R. A. & Lambin, X. Patterns and processes of dispersal behaviour in arvicoline rodents. Mol. Ecol. 21, 505–523 (2012).

Gauffre, B., Petit, E., Brodier, S., Bretagnolle, V. & Cosson, J. F. Sex-biased dispersal patterns depend on the spatial scale in a social rodent. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 276, 3487 (2009).

Lidicker, W.Z. Jr. The role of dispersal in the demography of small mammals, in Small Mammals: their production and population dynamics. Eds F.B. Golley, K. Petrusewicz and L. Ryszkowski, 103–28 (Cambridge University Press, London, 1975).

Gaines, M. S. & McClenaghan, L. R. Dispersal in small mammals. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 11, 163–196 (1980).

Swingland, I. R. & Greenwood, P. J. The Ecology of Animal Movement (Clarendon Press, 1983).

Burton, C., Krebs, C. J. & Taylor, E. B. Population genetic structure of the cyclic snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus) in southwestern Yukon, Canada. Mol. Ecol. 11, 1689–1701 (2002).

Plante, Y., Boag, P. T. & White, B. N. Microgeographic variation in mitochondrial DNA of meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus) in relation to population density. Evolution 43, 1522–1537 (1989).

Encuesta sobre superficies y rendimientos del cultivo 2012. Catálogo de publicaciones de la Administración General del Estado (MAGRAMA, 2013).

Oñate, J. J. et al. Programa piloto de acciones de conservación de la biodiversidad en sistemas ambientales con usos agrarios en el marco del desarrollo rural. Convenio de colaboración entre la Dirección General para la Biodiversidad (Ministerio de Medio Ambiente) y el Departamento Interuniversitario de Ecología (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, 2003).

Ji, S. et al. Impact of different road types on small mammals in Mt. Kalamaili Nature Reserve. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 50, 223–233 (2017).

Vignieri, S. N. Streams over mountains: influence of riparian connectivity on gene flow in the Pacific jumping mouse (Zapus trinotatus): connectivity patterns in pacific jumping mice. Mol. Ecol. 14, 1925–1937 (2005).

Russo, I.-R.M., Sole, C. L., Barbato, M., von Bramann, U. & Bruford, M. W. Landscape determinants of fine-scale genetic structure of a small rodent in a heterogeneous landscape (Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park, South Africa). Sci. Rep. 6, 29168 (2016).

Mougeot, F., Lambin, X., Rodríguez-Pastor, R., Romairone, J. & Luque-Larena, J.-J. Numerical response of a mammalian specialist predator to multiple prey dynamics in Mediterranean farmlands. Ecology 100, e02776 (2019).

Schwartz, M. K. & McKelvey, K. S. Why sampling scheme matters: the effect of sampling scheme on landscape genetic results. Conserv. Genet. 10, 441 (2009).

Strauss, W. M. Preparation of genomic DNA from Mammalian tissue. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 42, 1–3 (1998).

Ishibashi, Y. et al. Polymorphic microsatellite DNA markers in the field vole Microtus montebelli. Mol. Ecol. 8, 163–164 (1999).

Gauffre, B., Galan, M., Bretagnolle, V. & Cosson, J. Polymorphic microsatellite loci and PCR multiplexing in the common vole, Microtus arvalis. Mol. Ecol. Notes 7, 830–832 (2007).

Johnson, P. C. D. & Haydon, D. T. Software for quantifying and simulating microsatellite genotyping error. Bioinform. Biol. Insights 1, 71–75 (2009).

Paradis, E. pegas: an R package for population genetics with an integrated–modular approach. Bioinformatics 26, 419–420 (2010).

Brookfield, J. F. A simple new method for estimating null allele frequency from heterozygote deficiency. Mol. Ecol. 5, 453–455 (1996).

Adamack, A. T. & Gruber, B. PopGenReport: simplifying basic population genetic analyses in R. Methods Ecol. Evol. 5, 384–387 (2014).

Jones, O. R. & Wang, J. COLONY: a program for parentage and sibship inference from multilocus genotype data. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 10, 551–555 (2010).

Keenan, K., McGinnity, P., Cross, T. F., Crozier, W. W. & Prodöhl, P. A. diveRsity: An R package for the estimation and exploration of population genetics parameters and their associated errors. Methods Ecol. Evol. 4, 782–788 (2013).

Coulon, A. genhet: an easy-to-use R function to estimate individual heterozygosity. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 10, 167–169 (2010).

Coltman, D. W., Pilkington, J. G. & Pemberton, J. M. Fine-scale genetic structure in a free-living ungulate population. Mol. Ecol. 12, 733–742 (2003).

Amos, W. et al. The influence of parental relatedness on reproductive success. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 268, 2021–2027 (2001).

Aparicio, J. M., Ortego, J. & Cordero, P. J. What should we weigh to estimate heterozygosity, alleles or loci? Estimating heterozygosity from neutral markers. Mol. Ecol. 15, 4659–4665 (2006).

Kamvar, Z. N., Tabima, J. F. & Grünwald, N. J. Poppr: an R package for genetic analysis of populations with clonal, partially clonal, and/or sexual reproduction. PeerJ 2, e281 (2014).

Peakall, R. & Smouse, P. E. GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research—an update. Bioinformatics 28, 2537–2539 (2012).

Hedrick, P. W. A standardized genetic differentiation measure. Evolution 59, 1633–1638 (2005).

Jost, L. GST and its relatives do not measure differentiation. Mol. Ecol. 17, 4015–4026 (2008).

Meirmans, P. G. & Hedrick, P. W. Assessing population structure: FST and related measures. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 11, 5–18 (2011).

Nei, M. Analysis of gene diversity in subdivided populations. PNAS 70, 3321–3323 (1973).

Nei, M. & Chesser, R. K. Estimation of fixation indices and gene diversities. Ann. Hum. Genet. 47, 253–259 (1983).

Bowcock, A. M. et al. High resolution of human evolutionary trees with polymorphic microsatellites. Nature 368, 455–457 (1994).

Takezaki, N. & Nei, M. Genetic distances and reconstruction of phylogenetic trees from microsatellite DNA. Genetics 144, 389–399 (1996).

Smouse, P. E. & Peakall, R. Spatial autocorrelation analysis of individual multiallele and multilocus genetic structure. Heredity 82, 561–573 (1999).

Queller, D. C. & Goodnight, K. F. Estimating relatedness using genetic markers. Evolution 43, 258–275 (1989).

Ritland, K. Estimators for pairwise relatedness and individual inbreeding coefficients. Genet. Res. 67, 175–185 (1996).

Lynch, M. & Ritland, K. Estimation of pairwise relatedness with molecular markers. Genetics 152, 1753–1766 (1999).

Jombart, T. adegenet: a R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 24, 1403–1405 (2008).

Legendre, P. Spatial autocorrelation: Trouble or new paradigm?. Ecology 74, 1659–1673 (1993).

Zuur, A., Ieno, E. N. & Smith, G. M. Analyzing Ecological Data (Springer, Berlin, 2007).

Hedges, L. V. & Olkin, I. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis (Academic Press, 2014).

Kirby, K. N. & Gerlanc, D. BootES: an R package for bootstrap confidence intervals on effect sizes. Behav. Res. Methods 45, 905–927 (2013).

Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 112, 155–159 (1992).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (Academic Press, 2013).

González-Esteban, J. & Villate I. Microtus arvalis Pallas, 1778. In: Atlas y Libro Rojo de los Mamíferos Terrestres de España, Palomo, L.J., Gisbert, J. & Blanco J.C. (Eds.), Dirección General para la Biodiversidad-SECEM-SECEMU, 426-428 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by I+D National Plan Projects of the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness (TOPILLAZO-CGL2011-30274 and MOVITOPI-CGL2015-71255-P), Fundación BBVA Research Project TOPIGEPLA (2014 call) and MAPAMA/TRAGSATEC to GREFA (biological control program). We are very grateful to all people who helped with samples collection specially to Vega Santos, Ana Santamaría, Francisco Díaz Ruiz, Julian Núñez Conde, Xurxo Piñeiro and all workers and volunteers of GREFA. Julio C. Dominguez was supported by a predoctoral grant: “Programa Talento Formación” funded by Fondo Social Europeo (FSE) and Castilla La Mancha regional government (JCCM) (ref:SBPLY/16/180501/000205).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C.D., J.T.G., J.V., P.P.O. and J.E.M. conceived the study. J.C.D., J.T.G. and S.I. collected the samples. J.C.D. and M.C.R. performed the lab work. J.C.D. analyzed the data guided by M.C.R., P.P.O., J.E.M., C.B., K.P., S.I. and J.T.G. J.C.D. led the writing and the rest of authors contributed to editing and reviewing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dominguez, J.C., Calero-Riestra, M., Olea, P.P. et al. Lack of detectable genetic isolation in the cyclic rodent Microtus arvalis despite large landscape fragmentation owing to transportation infrastructures. Sci Rep 11, 12534 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91824-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91824-w

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.