Abstract

Study design

The study used a generic qualitative design.

Objectives:

This article set out to garner knowledge of peer mentorship programs delivered by SCI community-based organizations by interviewing people who are directly and in-directly involved with these programs.

Setting

Four provincial community-based SCI organizations across Canada. An integrated knowledge translation approach was applied in which researchers and SCI organization members co-constructed, co-conducted, and co-interpreted the study.

Methods

Thirty-six individuals (N = 36, including peer mentees, mentors, family members of mentees, and organizational staff) from four provincial SCI community-based organizations were interviewed. The participants’ perspectives were combined and analyzed using a thematic analysis.

Results

Two overarching themes with respective subthemes were identified. Mentorship Mechanics describes the characteristics of mentors and mentees and components of the mentor-mentee relationship (e.g., establish a common ground). Under the theme Peer Mentorship Program Structures, participants described the organizational considerations for peer mentorship programs (e.g., format), and organizational responsibilities (e.g., funding; creating a peer mentorship team).

Conclusion

This study provides an in-depth look at the characteristics of peer mentorship programs that are delivered by community-based organizations in Canada and highlights the complexity of delivering such programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Community-based spinal cord injury (SCI) organizations provide programs to help individuals with SCI manage the realities of living with a disability and enable them to thrive. One of the key programs within SCI community-based organization is peer mentorship [1]. In Canada, provincial SCI community-based organizations have been providing peer mentorship programs within community, rehabilitation centers, and hospital settings for past 7–71 years [1]. Peer mentorship in SCI consists of a peer interaction that aims to help individuals who share similar lived experiences adapt and/or thrive (www.mcgill.ca/scipm) where peers are seen as highly credible, equitable, and accepting [2]. Peer mentorship has been found to benefit people with SCI on a number of outcomes such as SCI knowledge, quality of life, and participation [3]. Randomized controlled trials of SCI peer mentorship have also found greater self-efficacy [4] and self-management skills [5] among participants who participated in a peer mentorship intervention compared to a control group. Our companion qualitative paper outlined the outcomes related to peer mentorship within Canadian SCI community-based organizations which identified outcomes of understanding, confidence, hope, and reduced isolation. Despite the growth in SCI peer mentorship research, few studies have focused on programs that are delivered by SCI community-based organizations.

Peer mentorship programs delivered by SCI community-based organizations differ from intensive, research-based peer-led interventions. These programs are multi-purposed and have a broad scope and use various modalities and strategies to deliver the program. Alternatively, peer-led research interventions are often very defined in scope and target-specific behaviors and outcomes such as self-management [5]. Barclay and Hilton [6] also highlighted in their scoping review that SCI peer mentorship remains highly varied in terms of timing, duration, location, and even if training was conducted (if at all). In describing peer mentorship, Veith et al. provided some insights into factors that facilitated mentor-mentee matching such as availability, age, gender, and interest [2]. Furthermore, Gainforth et al. documented high-quality characteristics of peer mentors [7]. These studies offer preliminary insights into the mechanics of peer mentoring but do not provide an understanding of the organizational considerations or characteristics of peer mentorship programs delivered by SCI community-based organizations.

A holistic strategy to understand peer mentorship programs delivered by SCI community-based organizations is needed. Such a need was highlighted by our partnered organizations given the data could help organizations obtain more resources (i.e., staff and funding) for these programs [1]. Capturing a comprehensive picture of SCI peer mentorship could illustrate the many decisions that community-based organizations must make when designing and delivering SCI peer mentorship programs. Therefore, the purpose of our study was to garner knowledge of peer mentorship programs delivered by SCI community-based organizations by interviewing people who are directly and indirectly involved with these programs. This qualitative study was led by the following research question: What are the characteristics of peer mentorship programs delivered within community-based organizations?

Methods

Design

Four provincial community-based SCI organizations and researchers from two universities established a community–university partnership to examine SCI peer mentorship. Using the IKT guiding principles for SCI research [8], all members assisted with the funding application and co-development of the research studies. For this paper, the research team includes two directors of community-based SCI organizations (HF, TC), academic researchers with SCI research and qualitive experience (SS, HG), LS, a qualitative research expert, and graduate students (LH, SH, OP). Multiple team meetings were held to collaboratively decide on the research questions, interview guides, and recruitment strategy, and provide interpretations on the results based on our experiences (see Appendix A). LH, a graduate student, was the primary interviewer, was trained by LS, and completed SCI educational modules prior to conducting the interviews.

A constructivist, interpretivist, approach with a relativist ontology was used as our qualitative paradigm. By using this paradigm, we believe that knowledge is socially constructed and reality is relative to the individual and the context. As such, we attempted to examine the multiple perspectives of individuals involved in SCI peer mentorship rather than to find a transcendental “Truth” [9]. Given this approach, we used a generic qualitative design to allow us to explore participants’ opinions and reflections of peer mentorship programs [10, 11].

Participants and procedures

Using purposeful sampling, participants were either a: (1) peer mentee (i.e., received peer mentorship), (2) peer mentor (i.e., provided peer mentorship), (3) family member of mentee, or (4) staff (with or without a SCI) of four community-based SCI organizations. Eligible participants were at least 18 years of age, English or French speaking, and were not diagnosed with a cognitive impairment. Research ethics certificates were obtained from McGill University and University of British Columbia.

Once informed consent was obtained, the participants then completed a single 45 to 60-min one-on-one interview over the telephone or via Skype®. Using a semi-structured interview guide, participants were asked questions surrounding the process of delivering and receiving peer mentorship, their peer mentorship experience, their role, and the impact peer mentorship had on their lives or the lives of the mentees from the perspective of staff members or the mentees’ family members (See Appendix B). The transcripts were transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

We used a thematic analysis approach to analyze our data [12]. First, LH read the interview transcripts multiple times to familiarize herself with the data. Line by line, she identified initial codes (i.e., meaningful portions of data relevant to the research questions) in each transcript. SS then reviewed the codes. Over 2 days, LH, SS, and a research assistant re-examined each code for relevance and then grouped relevant codes into themes and sub-themes. Once these initial themes were identified, six rounds of discussion were held between LH, SS, and SH to continue to collapse themes and create definitions for each theme. All codes and resulting themes were therefore based on participants’ responses and researchers’ interpretations (i.e., analyzed inductively), aligning with a constructivist paradigm. Community partners (HF and TC) were community-based critical friends. They proposed changes or questioned the researchers on the relevance of themes based on their experiences. Note that OP and SH further refined the themes following reviewer comments and these modified themes were verified by both community partners. Therefore, multiple researchers were involved in the analysis, which ensured reliability and credibility. We also used an audit trail (documented details about recruitment, data collection and data analyses) and critical friends (academics and executive directors) as ways to ensure rigor in our analysis and trustworthiness of our data. Critical friends included the directors of the programs as they provided a soundboard to enhance reflexivity around the data (i.e., the data reflected participants’ experiences in SCI peer mentorship) [10]. These indicators enhanced the credibility of our data through multivocality [13].

Results

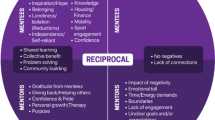

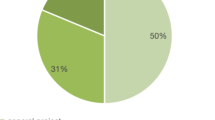

Thirty-six participants (N = 36) completed the interviews (peer mentees, n = 9; peer mentors, n = 13; family, n = 6; and staff, n = 8;see Table 1). We presented the results over two broad themes—Mentorship Mechanics and SCI Peer Mentorship Program Structures—with sub-themes highlighted in italics (Fig. 1). Additional quotes supporting the sub-themes are in Tables 2 and 3.

Mentorship mechanics

Mentor characteristics

As per our participants, the Reasons to become mentors are to help others and be able to share their Lived Experiences/Expertise: “you can be a mentor in different silos, depending on your expertise, your skills”; Kenneth, mentor, complete tetraplegia). Effective mentors have various Interpersonal Skills (e.g., active listening, openness to others and experiences) and Qualities (e.g., patience, positive attitude, trustworthiness) when interacting with their mentees.

“I repeatedly had the experience of approaching someone and telling them who I was, and then get them to talk about themselves. They would walk away with the opinion that I was really a smart fellow who understood all the issues. I had just listened to them talk about themselves. We started on a relationship of trust, and that struck them often as that’s a really clever fellow [laughter]. All I had done was listen.” Kevin (Staff who is also a mentor, Incomplete Paraplegia)

These skills and qualities facilitate the Emotional support provided by mentors through their empathic understanding. As highlighted by our participants, the mentors engage with their mentees by Maintaining Agency of their mentees to help them achieve their own goals. Lastly, mentors maintain a level of Professionalism in their interactions with mentees.

Mentee characteristics

Mentees have different Motivations for mentorship including wanting to “change the way of my life” (Sam, mentee, incomplete paraplegia). A mentee will likely come into a mentorship experience to gain Control/Agency because “we live for that control. The more and more that you desire that control, the more and more you push yourself to do these things.” (Susan, mentor, incomplete tetraplegia).

Mentor/mentee relationships

The peer mentor–mentee relationship often starts on Common Ground because “When they [mentors] come wheeling into your room, that speaks volumes as opposed to somebody comes walking into the room. You don’t even have to say it, you’re living it and they’re seeing it.” (Charles, staff, no SCI). However, it is important to Clear Objectives regarding the mentor/mentee relationship and program expectations. Ultimately, the mentorship relationship should be focused on the mentees’ needs and interests as they change over time and with different stages of life (Mentee Focused Mentorship Provision).

Readiness of the mentee are also key elements for the mentor/mentee relationship because the “mentee’s got to be in the right frame of mind and want it. And then the mentor’s got to be—they got to be the right fit, the right connection.” (David, mentee, complete paraplegia). The mentor/mentee relationship is Dynamic because sometimes the mentor can become a mentee in the sense that they “…always looking to learn from each other because ultimately there’s no better source of knowledge.” (Donald, mentor, incomplete tetraplegia). As a result, mentors and mentees can develop Relationships that endure over time, however, Boundaries around friendship need to be clarified because “I don’t think a mentor–mentee relationship is the same as a friend relationship. Sometimes the lines are blurred.” (Kenneth, mentor, complete tetraplegia).

Content of mentorship discussion

Participants highlighted 15 different Life skills that are discussed in a mentorship interaction (i.e., conversation or observation) such as skills for bladder and bowel management, sexual/intimacy, and transition into the community after rehabilitation (Table 2). General Information/Advice is also shared in peer interactions as well as discussions to help Family. Mentorship programs also introduce people to Sports, Recreation, and Physical Activity opportunities.

SCI Peer Mentorship Program Structures

Program considerations for SCI Peer Mentorship

Organization have different venues by which Introductions to peer mentorship are made. Participants expressed that peer mentorship has been introduced in sports, during community events, and in rehabilitation: “rehab time now is so short and so compact. And with a community-based organization having a staff person who has a SCI, it can build that peer mentorship role right from the start.” (Charles, Staff, No SCI). Once introductions are made, peer mentorship can than take on different Formats from formal (i.e., structured and specific) and/or informal (i.e., open, unstructured) interactions and can have a variety of Modes of Delivery (e.g., face-to-face, online). A staff member said: “…a more formalized structure [enables us to] create more interactions and more touchpoints with people seeking [to gain] life experience, to make choices, or learn to get past the journey to recovery and living life with spinal cord injury.” (Jeffrey, staff, complete tetraplegia). By contrast, Kenneth, a mentor with complete tetraplegia who was previously a mentee discussed the power of informal interactions (see Table 3).

In interviewing families of people with SCI, family members discussed the need and usefulness of Peer Support for Families. For example, Lisa relived her experience of looking for mentorship, as a family member, while her partner was in the hospital:

I stayed at the hospital for the first few days overnight, but I was never alone, but I never felt more alone. It was f’ing awful… I asked the hospital…is there a list I can be put on? Can I talk to somebody who lived this? Is there some group that I can reach out to or connect with? And there wasn’t one.

Organizational Responsibilities

SCI organizations that deliver peer mentorship programs have several responsibilities in ensuring the programs can be sustained and are delivered effectively. In maintaining peer mentorship programs, organizations must continuously build Collaborations with other organizations and/or the health sector. They are simultaneously applying and seeking Funding to support program delivery. The Visibility and Access of these peer mentorship programs can be achieved via promotion and by providing multiple access points. One method to promote programs is by organizing events as Charles, a staff without SCI, explains:

In [my province], we’ve got Jessica. She hosts different events at the hospital. They have a pizza night for the new injuries at the hospital. They have a restaurant group where they go out to various restaurants. They also have other scheduled events that might be topic specific. They’ve held a few peer conferences and had various speakers come out to a peer conference.

Organizations must also Create a Peer Mentorship Team by identifying and selecting mentors and hiring experienced staff (Table 3). Mentors can either paid or volunteers and are often identified through their previous involvement within the organizations as Michael, a staff with incomplete paraplegia, highlights: “It’s more or less we know them. We’ve seen them at events four or five times…We sort of pull from a pool that’s been developed over years of trust.” Participants highlighted the importance of hiring staff that have educational backgrounds and/or experience to work within this domain because running such programs can be rewarding but demanding. It may require staff to be flexible:

When I first started working here, I’d do the work in the office, [but] now I find myself taking my work at home and working on projects… I also answer calls and emails on the road. I get emails sometimes like, “I think my son might be depressed or borderline suicidal.” I don’t wait until I get back to the office…I call that person.” (Michael, Staff, incomplete paraplegia).

In delivering peer mentorship programs, organizations have the responsibility of creating Mentorship Matches that consider the needs of the mentees including their interest, disability severity, and gender: “And obviously, being a woman and having SCI is a lot different than being a man with SCI. We just have different things that we question or want to learn about or know about that you can only learn that from another woman.” (Linda, Mentor, Incomplete Tetraplegia). Mentors should also be provided with opportunities for Training to build their skills (Table 3).

Organizations must also be aware of and address Barriers that mentees face to accessing peer mentorship whether it be transportation or psychological barriers. As Lisa, a family member, expressed that “they [people with SCI] are just so down in a pit and in a black hole. They cannot see how it [mentorship] would benefit them.”. Participants highlighted the organizations’ need to continuously adapt to the barriers and challenges related to the themes above but also to the potential growth of the program (see Table 3).

Discussion

Our results shed light on the intricacies of peer mentorship programs delivered by SCI community-based organizations. There are many layers of peer mentorship delivery that include the operational decisions (funding, formats, visibility, building a peer mentorship team) that include selecting mentors that have strong interpersonal skills and qualities. Delivering such programs is therefore not a simple enterprise and requires a concerted and continuous effort by the organizations to sustain these programs over time. This study can provide some insights into the components and characteristics of peer mentorship programs that could help community-based programs who want to develop these programs.

Mentor characteristics and approaches were key features in describing the role of mentors. Our participants highlighted that mentors are seen as credible individuals [14], who are willing to help others [15], and are open to experiences [16], They also interacted with mentees using interpersonal strategies (e.g., active listening) and qualities. A growing body of research in SCI peer mentorship is finding that interpersonal strategies that align with person-centered approaches are highly valuable. For example, Shaw et al. found that mentors exhibited person-centered and leadership skills and qualities that related to the four dimensions of transformational leadership. Specifically, they were open and honest (idealized influence), enthusiastic and encouraged achievements (inspirational motivation), responsive and caring to mentees’ needs (individualized considerations), and promoted independent thinking (intellectual stimulation) [17]. Similarly, Chemtob et al. demonstrated that mentors involved mentees in the decision-making process, provided positive encouragement/feedback, and had an empathic understanding which, respectively, link to autonomy, competence, and relatedness supportive interpersonal behaviors within self-determination theory [18]. Our results therefore align with these studies and person-centered theories such as transformational leadership and self-determination theory.

However, support systems in SCI (including mentorship) need to be “vigilant for the thresholds of readiness for choice and control” (p. 9) of the person being supported, especially where power dynamics could be in play [19]. Peer mentors may want to promote choice and control by having mentees engage in a reflective process, self-express, find purposely goals/activities, and be open to new realities, roles, and activities with living with SCI [19]. Such action could help mentees establish a mindset of being an active agent in their peer mentorship. There appears to be a convergence that peer mentorship should be delivered using person-centered approaches. However, data on the specific techniques used by peer mentors are only now emerging [20]. These emerging results and findings from this study can help optimize peer mentorship training to promote mentors to use person-centered approaches in their practice.

From a practical standpoint, community-based organizations may want to measure mentees’ perception of the quality of their interactions with their mentors to understand the interpersonal behaviors and approaches of their mentors. Despite the high-quality mentor characteristics identified in this study, low quality mentor characteristics such as low motivation, judgmental, and uncaring have been reported in the literature [21]. Questionnaire such as the Interpersonal Behavioral Questionnaire can provide information on mentees’ perception of their mentors’ approach (example items: provide valuable feedback, encourage them to make their own decisions, take time to get to know them) [22]. Such assessments could help understand mentee’s perception on the quality of the mentors. Knowing the extent to which mentors are delivering high-quality, person-centered mentorship may help to inform other organizational decisions such as selecting and training mentors and establishing criteria for mentor–mentee matches.

Community-based organizations that provide peer mentorship continuously seek funding for the programs, and typically have little human resources. As a result, a select few dedicated (and likely overstretched) staff need to wear multiple hats [23] to run such programs and rely on volunteers. Further, Gibson and O’Donnell [24] discussed that project-based funding for community organizations adds strain on the organization as they need to dedicate more hours for writing funding applications and reports and may require staff to work over and above logged hours. Continuous guaranteed funding for these programs would reduce the burden on these organizations. It would allow staff within these organizations to dedicate more time on other important organizational responsibilities. For example, organizations could work to foster strong collaborations with new hospital, health care providers, researchers, and community organization to help increase the visibility and access of peer mentorship. They could also create new training modules for mentors and/or develop new modes of peer mentorship delivery. Transferring staffs’ time and effort from funding application to building collaborations and optimizing peer mentorship delivery could increase the current SCI peer mentorship adoption rate of 2% in Canada [1].

Participants mentioned the importance of providing mentorship for family members. This appears to be a growing need across disability and health domains. In the SCI context, Haas et al. [25] reported on the benefits of peer mentorship for families because they appreciated the psychological support and having someone who understood. Therefore, identifying how to best support the role of family members and “caregivers” need to be further investigated [26].

Limitations

There are some limitations of this study that should be addressed. First, we did not differentiate the participants by province, mentorship role, and time since received or provided mentorship. Also, this study was solely conducted on Canadian SCI community-based peer mentorship programs. Future studies should examine the similar SCI programs across the world to gain a broader perspective of how these programs are structured and delivered [27].

Conclusion

This study describes the many aspects involved in SCI peer mentorship programs delivered by community-based organizations. Organizations could use the information from this study to understand the various elements that need to be considered when designing a peer mentorship program for people with SCI (e.g., format of program, mode of delivery, funding considerations) and identifying and selecting mentors. These results also put in perspective the dedication of directors, staff, and mentors who successfully manage the complexity of programs and ensure their success.

Data availability

Upon request, the datasets of this study can be made available from the corresponding author.

References

Shaw RB, Sweet SN, McBride CB, Adair WK, Martin Ginis KA. Operationalizing the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, maintenance (RE-AIM) framework to evaluate the collective impact of autonomous community programs that promote health and well-being. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:803.

Veith E, Sherman J, Pellino T, Yura Yasui N. Qualitative analysis of the peer-mentoring relationship among individuals with spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2006;54:289–98.

Rocchi MA, Shi Z, Shaw RB, McBride C, Sweet SN. Identifying the outcomes of participating in peer mentorship for adults living with spinal cord injury: a qualitative meta-synthesis. Psychol Health. 2021:1–22. online ahead of print.

Gassaway J, Jones ML, Sweatman WM, Hong M, Anziano P, DeVault K. Effects of peer mentoring on self-efficacy and hospital readmission after inpatient rehabilitation of individuals with spinal cord injury: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:1526–34.

Houlihan BV, Brody M, Everhart-Skeels S, Pernigotti D, Burnett S, Zazula J, et al. Randomized trial of a peer-led, telephone-based empowerment intervention for persons with chronic spinal cord injury improves health self-management. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:1067–76.

Barclay L, Hilton GM. A scoping review of peer-led interventions following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2019;57:626–35.

Gainforth HL, Hoekstra F, McKay R, McBride C, Sweet S, Martin Ginis KA, et al. Integrated knowledge translation guiding principles for conducting and disseminating spinal cord injury research in partnership. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2020.09.393.

Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26:13–24.

Bradbury-Jones C, Breckenridge J, Clark MT, Herber O, Wagstaff C, Taylor J. The state of qualitative research in health and social science literature: a focused mapping review and synthesis. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2017;20:627–45.

Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.; 1994. p. 105–17.

Sparkes, AC, Smith, B. Qualitative research methods in sport, exercise, and health. New York, USA: Routledge; 2014

Braun V, Clarke V, Weate P. Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In: Smith B, Sparkes A, editors. Routledge handbook of qualitative research methods in sport and exercise. London, UK: Routledge; 2016. p. 191–205.

Tracy SJ, Hinrich MM. Big tent criteria for qualitative quality. In: Davis CS, Potter RF, editors. The international encyclopedia of communication research methods: JohnWiley & Sons, Inc; 2017. p. 1–10.

Reis HT, Lemay EP Jr., Finkenauer C. Toward understanding understanding: the importance of feeling understood in relationships. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2017;11:e12308 https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12308

Divanoglou A, Georgiou M. Perceived effectiveness and mechanisms of community peer-based programmes for spinal cord injuries: a systematic review of qualitative findings. Spinal Cord. 2017;55:225–34.

Hoffmann DD, Sundby J, Biering-Sørensen F, Kasch H. Implementing volunteer peer mentoring as a supplement to professional efforts in primary rehabilitation of persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2019;57:881–9.

Shaw RB, McBride CB, Casemore S, Martin Ginis KA. Transformational mentoring: leadership behaviors of spinal cord injury peer mentors. Rehabil Psychol. 2018;63:131–40.

Chemtob K, Caron JG, Fortier MS, Latimer-Cheung AE, Walter Z, Sweet SN. Exploring the peer mentorship experiences of adults with spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2018;63:542–52.

Murray CM, Van Kessel G, Guerin M, Loris Hiller S. Exercising choice and control: a qualitative meta-synthesis of perspectives of people with a spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100:1752–62.

McKay RC, Baxter KL, Giroux EE, Casemore S, Clarke TY, McBride CB, et al. Investigating how peer mentorship supports people with spinal cord injury. Analyzing and characterizing peer mentorship conversations. 57th International Spinal Cord Society Annual Scientific Meeting; Sydney, Australia; 2018.

Gainforth HL, Giroux EE, Shaw RB, Casemore S, Clarke TY, McBride C, et al. Investigating characteristics of quality peer mentors with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100:1916–23.

Rocchi M, Pelletier L, Cheung S, Baxter D, Beaudry S. Assessing need-supportive and need-thwarting interpersonal behaviours: The interpersonal behaviours questionnaire (IBQ). Pers Individ Dif. 2017;104:23–433.

Gibson K, O’Donnell S, Rideout V. The project-funding regime: complications for community organizations and their staff. Can Public Adm. 2007;50:411–36.

Gibson K, O’Donnell S, Rideout V. The project-funding regime: complications for community organizations and their staff. Can Public Adm. 2007;50:411–36.

Haas BM, Price L, Freeman JA. Qualitative evaluation of a community peer support service for people with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:295–9.

McKay RC, Wuerstl KR, Casemore S, Clarke TY, McBride CB, Gainforth HL. Guidance for behavioural interventions aiming to support family support providers of people with spinal cord injury: a scoping review. Soc Sci Med. 2020;246:112456.

Bucknall T. Bridging the know-do gap in health care through integrated knowledge translation. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2012;9:193

Acknowledgements

SS is funded through the Canada Research Chair program as Canada Research Chair in Participation, Well-being, and Physical Disability. HG is funded through a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar Award [#16910]. Thank you to SCI British Columbia, SCI Ontario, SCI Alberta, and Ability New Brunswick for assisting in participant recruitment. A special acknowledges for the time and dedication of Samantha Taran, Meaghan Osborne, and Kaila Bonnell for helping at different phases of this study.

Author contributions

The study was co-conceptualized and co-designed by the community directors (TC and HF) and academic researchers (SS, LS, and HG). All these members were also involved in co-construction of the interview guides. LH interviewed participants and led the data analysis with SS and SH. All authors were involved in the final writing and editing of this manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. HG is supported by a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar Award (MSFHR, Canada, no. 16910).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics

Ethics was approved from the Research Ethics Board at both McGill University and the University of British Columbia Okanagan. All applicable institutional and government regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were complied to in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sweet, S.N., Hennig, L., Pastore, O.L. et al. Understanding peer mentorship programs delivered by Canadian SCI community-based organizations: perspectives on mentors and organizational considerations. Spinal Cord 59, 1285–1293 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-021-00721-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-021-00721-6