Abstract

Teacher agency for research, which refers to teachers’ decision-making and initiative acts in the context of academic engagement, plays a pivotal role for teacher learning, teacher research, and thus teachers’ professional development. Despite the burgeoning number of studies that have examined teachers’ research and publishing experiences, it is unclear how university teachers exercise their agency for research in funding applications. This study examines how foreign language teachers at a university in China practice agency in the application of the National Social Science Fund of China from a Complex Dynamic Systems Theory perspective. Narrative frames and semi-structured interviews were used to collect the data, and thematic analysis was adopted to elucidate the complexity and dynamics of teacher agency for research. Revealing that there are subsystems of teacher agency for research in funding applications, i.e., agency beliefs, agency practice, and agency emotions and that the developmental trajectories of their agency for research are situated and relational, the findings highlight the need to view teacher agency as complex systems and dynamic entities. This study not only offers a conceptual framework as to unravel teacher agency for research in funding applications but also provides a tentative pathway for teachers exercising agency in applying for external funding both in the context of China and beyond.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the aim of realizing the “high-quality development” (“高质量发展”)Footnote 1 of higher education, university teachers’ well-being and professionalism for high-quality teacher development (Wang and Zhang 2023) is a sine qua non. Teacher agency which is defined as teachers’ capacity to initiate intentional acts (Bandura 2006) has been researched extensively in the past two decades, thus is considered to be a key attribute for teachers’ professional development (Toom et al. 2015; Priestley et al. 2015). Apart from ample studies on how teacher agency influences teaching practices (Tao and Gao 2017; Hiver and Whitehead 2018; Ruan et al. 2020; Ruan 2021; Heikkilä and Mankki 2023; Kusters et al. 2023), academics have also shown interest in teacher agency for research because teachers’ research engagement provides opportunities for teachers to enhance teaching and learning and to build their sense of agency and professional voice (Taylor 2017). Teachers, as researchers, are expected to be involved in ongoing systematic inquiries as a key element of their work (Hökkä et al. 2012). Existing literature has revealed teachers’ identity commitment in their research practice—there are challenges and complexities in the language teacher educator’s identity construction as a researcher (Yuan 2017); power relations entail tensions in EFL teachers’ research practice and researcher identity construction (Lu and Yoon 2022); and domestic visiting study programs and professional learning groups play a role in facilitating teachers becoming researchers (Bao and Feng 2022; Zeivots et al. 2022). While the findings of these studies have generated important insights into the construction of teachers’ identities as researchers, how teacher agency affects change in their funding application experiences is rarely investigated.

Due to the influence of Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) and a culture of “publish or perish”, university teachers face mounting pressure regarding both research productivity and research quality (Murray and Male 2005; Yuan 2021). The amount of funding obtained from external sources is applied as a performance measure across all levels of aggregation, ranging from national systems of performance-based funding of universities down to decisions concerning individual positions (Laudel 2005). It has been argued that research funding in China contributes to the sustainable growth of scholarly disciplines in the arts and humanities (Jiang et al. 2020). As one of the most important research programs in China, “The National Social Science Fund of China” (NSSFC) (“国家社会科学基金”) is considered to be “playing a leading role in promoting the development of the country’s philosophy and social sciences” (Zhou 2015, p.51). The success of NSSFC funding is adopted not only as a benchmark for the comprehensive strength of a university but also as a cornerstone in teachers’ developmental trajectories, as academic outputs are increasingly emphasized in performance evaluation and the university employment system in higher education. For in-service teachers, receiving approval for national-level research funding and conducting relevant studies supported by the funding have become integral criteria for promotion at many universities in China.

This study focused on university foreign language teachers, who are usually considered to bear heavy teaching loads and receive less research training (Wang 2018). While universities usually have separate teaching-track staff to provide language training, most universities in mainland China still adopt a recruitment model in which language teachers are “on the teaching-research track, like academics in other disciplines” (Bao and Feng 2023, p.2). Often unable to fulfill their expected researcher identity, university foreign language teachers’ research engagement and productivity are constantly hindered (Xu 2014). Therefore, this study delves into the underexplored territory of how teacher agency impacts the experiences of university foreign language teachers in their funding applications, taking the application for NSSFC funding as an example.

NSSFC and relevant studies

In the quest to pursue the “Chinese dream” (“中国梦”) and achieve great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, the central committee of the CPC and the State Council promulgated “Double First Class” (“双一流”) as a strategic plan for higher education to build first-class universities and disciplines worldwide. China has implemented proactive management practices to ensure that universities excel in research and academic quality assessment with the aim of establishing world-class universities and disciplines. This initiative has led to increased emphasis on research performance among university professionals due to the commitment to achieving global excellence in academia.

Although social science researchers worldwide face the threat of funding cuts when many governments are more willing to invest in hard sciences research (Ware and Mabe 2015; Hamann 2016), the Chinese government invests relatively generously in the Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS). The development of HSS research is of strategic importance to the central government (Gao and Zheng 2018). As President Xi Jinping pointed out at the Meeting of National Philosophy and Social Sciences Academics in 2016, “In the course of upholding and developing socialism with Chinese characteristics, philosophy and social sciences play an irreplaceable role”, accordingly, the academic work of HSS researchers in China sustains great responsibilities.

A brief synopsis of the NSSFC

The National Social Science Fund of China was established by the State Council in 1986. Over thirty years of development has led to the incorporation of 23 discipline planning assessment panels and three independent disciplines (educational science, art science, and military science) of the NSSFC. The funding system mainly supports six categories of research projects (Table 1).

In the first year of the “14th Five-Year Plan” (2021–2025, “十四五规划”) in China, the funding investment of the NSSFC reached a new high of 2.65 billion yuan in 2021, exhibiting a 3.3% increase (84.54 million yuan) over the previous year (Chu 2021). The National Office of Philosophy and Social Sciences announced a list of 4790 projects receiving grants on September 22nd, 2023, including 3578 annual projects (396 key projects, 3182 general projects) and 1212 youth projects; and 427 western projects on September 27th, 2023. Against the backdrop of increased emphasis on research over teaching (McKinley 2019), teaching-focused academics often grapple with identity struggles (Bao and Feng 2023). Since the initiation of the “Reform and Opening-up Policy” (“改革开放”) in China in 1978, English and other foreign languages have played crucial roles in the country’s development blueprint (Adamson 2004). At the tertiary level, foreign language proficiency is widely accepted not only as an essential skill but also as a prerequisite for graduation and a privilege for better job prospects (Xu 2014). This unwavering enthusiasm for foreign language learning has elevated expectations and standards for foreign language teachers in China, who juggle heavy teaching loads alongside research expectations. Despite this, foreign language teachers are perceived to have a weaker research tradition than teachers in other disciplines in the social sciences (Dai 2009). Therefore, the research practice of university foreign language teachers, fraught with a range of challenges, has become a bottleneck for their ongoing professional advancement.

To date, much of the existing research on foreign language teachers’ research engagement has focused primarily on academic writing and publication (Yuan 2017; Yuan 2021; Liu et al. 2022). However, there is a general lack of research on university foreign language teachers’ experiences in applying for funding. This study intends to fill this void by bringing to the fore university foreign language teachers’ experiences in NSSFC funding applications in the Chinese higher education context.

Studies on the NSSFC in China

As the highest level of research grants offered to HSS researchers in China, the directiveness, authority, and exemplariness of the NSSFC are becoming increasingly evident (Zhou 2015). For university foreign language teachers, the competition for NSSFCs in linguistics, foreign literature, Chinese literature, and other language-related disciplines is intensifying due to the limited funding given to a large cohort of applicants.

Several studies have centered on the NSSFC in the field of linguistics and literature: Wang and Jiang (2011) studied funding granted during the 11th Five-Year Plan (2006–2010, “十一五计划”) and found that areas of particular research interest included foreign language teaching, translation studies, linguistic studies, and functional linguistics; Liu and Zhu (2018) compared the approval trends in linguistics and literature from 2013 to 2017 (i.e., the growth of foreign linguistic research far outpaced the other language studies; and the number of foreign language and literature projects lagged seriously behind that of Chinese language and literature projects.); Su (2018), in her study of NSSFC in linguistics between 1991 and 2016, found that language studies were mainly concentrated in Project 985/211Footnote 2 universities and the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, most of which are in Beijing or other developed areas of China; Wang and Fan (2020) conducted a quantitative analysis of the NSSFC in translation studies between 2015 and 2019 and reported that the approval trend was guided by national strategic needs, for instance, Chinese culture goes global (“中国文化走出去”).

While these studies contribute to understanding NSSFC applications from a broad perspective, they fall short of demystifying the problems and challenges facing university foreign language teachers in the case of funding applications, how they have utilized their agency for research in securing external funding, and the intricacies of the application process. Unlike Wen and Lin (2017), who interviewed 14 NSSFC evaluation experts in an empirical study to reveal the strategies and attitudes involved in the review process in a “top-down” manner, this study aimed to address the nuances and complexities of foreign language teachers’ NSSFC application experiences in a “bottom-up” model, focusing on the applicants themselves rather than the evaluation experts.

Theoretical framework

Conceptualizing teacher agency

The concept of agency has been approached through multiple theoretical and methodological lenses. At times, agency has been characterized as a personal attribute, capacity, or competence that enables individuals to initiate intentional acts (Ahearn 2001; Bandura 2001). This characterization has been challenged by other researchers who assert that agency is more about what people do or achieve (Biesta et al. 2015; Priestley et al. 2015). The mediating role of context has also been acknowledged, assuming the reciprocal relationship between agency and the social, cultural, and interactional environment in which one’s agency develops (van Lier 2008). Individuals choose to act or not to act (Ruan and Toom 2022) because of the interactions between their capacities and the resources, affordances, and constraints of the environment (Priestley et al. 2015). Hence, individual agency can be understood in relation to the material and social world and what it affords or denies (Goller 2017).

Based on the abovementioned inclinations to conceptualize agency, it can be concluded that agency not only concerns individuals or groups who can take proactive actions or implement self-regulation but also entails the influence of social and cultural contexts, suggesting a dialectical and unified relationship between agency and the environment. According to Lantolf and Thorne (2006), agency is socioculturally mediated in a specific temporal and spatial context with restrictions and affordances coexisting, which allows individuals to possess varying degrees of ability to act, therefore, agency can be manifested as choice. The choice between taking action and not taking action depends on factors such as the context and the individual’s ability to interpret its relevance and significance. Therefore, individuals, by exercising agency, have the potential to take physical, cognitive, emotional, and motivational actions and make choices according to specific purposes (Teng 2019). The reason why some people are more inclined to take agentic action and are capable of doing so can be identified with three factors, i.e., agency beliefs, agency competence, and agency personality (Goller and Harteis 2017).

Teacher agency embodies a capacity that allows teachers to “learn actively and skillfully, regulate their own learning and the learning competencies needed in their work, develop professionally, promote students’ and colleagues’ learning, and innovate and promote change in schools” (Toom, et al. 2021, p.2). In recent climates, language teacher identity, because of its complexity, dynamics, and sociocultural turn, has received a great deal of attention from academics. Language teacher agency plays a significant role in the construction of multifaceted identities through decision-making and action (Kayi–Aydar 2019). A growing bulk of literature has uncovered the intricacies and dynamics of language teacher agency, for instance, the relations between experiences and actions outside the professional development classroom and language teacher agency (Feryok 2012); the dynamic interplay of discourse, agency, and teacher attrition (Trent 2016); the impact of working conditions, rhetoric, and culture for teacher agency and teacher retention (Bieler et al. 2016); the effect of practicum teaching on the construction of professional agency of teacher trainees (Ekşi et al. 2019); efforts to bridge research and practice for a language teacher becoming an agent of motivational strategies (Nakata et al. 2021); and the contextual factors that support or restrict teacher agency with regard to becoming action researchers (Mohamed Emam et al. 2023).

Theory and practice in the realm of language teacher agency have had certain implications for scholars in China, who are cognizant of the importance of teacher agency and have shown increased interest in research on the role of agency in the context of language education. There are three main strands of research on language teacher agency in China, i.e., language teacher agency in curricular reforms, language teacher agency in teaching practices, and language teacher agency for professional development (Xu and Zhang 2022). However, how in-service language teachers exercise their agency for research (especially in funding applications) to realize sustainable career development remains a relatively hazy notion. As mentioned above, language teacher agency plays an important role in the prosperous development of HSS in China with research in the literature, linguistics, translation studies, etc. Although academic performance (e.g., in terms of writing for publication or funding applications) should not become the only onus for university language researchers, it is viewed as their compelling obligation to flourish disciplinary development, promote mutual learning across civilizations, and establish a shared community for mankind (Wang and Fan 2020). At present, language teachers in China exhibit considerable satisfaction with their teaching, however, they are relatively dissatisfied with their research practices (Li and Wang 2021). Therefore, there is an urgent need to understand language teacher agency in their research engagement. In this study, it is claimed that teacher agency for research refers to teachers’ decision-making and initiative in their academic engagement. Teacher agency for research is viewed as a domain of teacher agency; thus, it shares the distinctive features of teacher agency in general. However, given the complex nature of academic engagement, especially funding applications, teachers can demonstrate their unique beliefs and practices and then exercise their agency for research in funding applications in a complex way.

Teacher agency from the perspective of complex dynamic systems theory

Various approaches have been employed to account for agency: performativity theory, sociocultural theory, sociocognitive theory, critical realism, etc. (Larsen-Freeman 2019). This study draws on the Complex Dynamic Systems Theory (CDST) to understand the dynamic and complex entity of teacher agency in funding applications.

Although CDST stems from Complex System Sciences (Larsen-Freeman 1997; Holland 2006), it has gained increasing attention in investigating the complexity and dynamics of development underlying social and cultural systems (Chen 2023). Described as living, open, and dynamic, complex dynamic systems consist of multiple levels of subsystems that interact with one another in a nonlinear way (Qi and Wang 2022). CDST posits that a system is a group of interconnected and interdependent elements that behave following a set of rules to constitute a cohesive whole (Backlund 2000). Complex systems are spatially and temporally situated and can achieve relative stability; furthermore, gradual and dynamic changes contribute to the emergent outcome of complex systems. As a meta-theory, CSDT integrates a set of relational principles (Overton 2013); that is, certain phenomena involve multiple parts interacting together through dynamic, nonlinear processes that lead to striking emergent patterns over time (Hiver and Al-Hoorie 2016).

The complex and emergent nature of teacher agency entails a systematic approach to exploring what the subsystems of teacher agency are and how these interdependent constituents work together to enact agency in response to a variety of professional tasks. CSDT is invoked as a theoretical perspective to underpin and guide the analysis of teacher agency in this study based on the following three considerations:

First, teacher agency is a complex entity that consists of numerous interrelated elements and dimensions. Goller and Harteis (2017) differentiated three facets of agency, namely, agency beliefs, agency competence, and agency personality, which are interdependent and together account for why some people are more prone to take agentic actions and are capable of doing so. Similarly, the reciprocal relationships between systems and their subsystems and between one subsystem and the other in a complex system can inspire an analysis of the different dimensions of teacher agency.

Second, as Emirbayer and Mische (1998) noted, agency is the influence of the past, engagement with the present, and an orientation toward the future. Therefore, teacher agency is spatially and temporally situated when context and time are essential parts when investigating a system (Ushioda 2015). Just as a complex system can achieve relative stability as a self-organizing attractor, teacher agency can manifest similar stability through the interplay between structure and agency (Larsen-Freeman 2019).

Third, agency is relational. According to Larsen-Freeman (2019), agency refers to the dynamic interaction of factors both internal and external to the system, which persist only through their constant interaction with each other. We establish, lose, and re-establish meaningful interactions between ourselves and our environment (Buhrman and Di Paolo 2017, p.216). This idea resonates with Ellis’s (2019) claim that agency is always related to affordances or restrictions in the context, which is ecological and is the relationship between the organism and the environment.

Against the backdrop of applied linguistics expanding from its two traditional background discipline orientations of linguistics and education (Zheng 2020) by increasingly incorporating theories and practices “from distant disciplines, such as complexity theory, which originated in mathematics, physics, and computer science” (Lei and Liu 2019, p. 18), a considerable number of studies have used CDST to demystify the nuances of language teacher agency. Hiver and Whitehead (2018) applied the CDST as an analytical framework to unravel four language teachers’ agency in a complex classroom setting to determine why and how situated adaptivity was enacted by them. Rostami and Yousefi (2020) adopted the CDST to explore the agency construction of 15 Iranian novice teachers and revealed that teachers practice agency by employing dialogic feedback, positioning, and critical incidents. Qi and Wang (2022) examined language teacher agency for research in a blended classroom by using CSDT as a theoretical framework to address both the challenges of teaching and the corresponding responses. These empirical studies shed light on the shared features of teacher agency and complex systems and improve our understanding of teacher agency by revealing its complex, dynamic, and interactive nature.

Thus far, most of the extant literature has focused on how language teachers exercise agency in the teaching milieu and how agency plays a role in teachers’ identity construction and reconstruction as researchers; however, it is relatively unclear how language teachers enact their agency for research in funding applications in a dynamic and complicated manner with the goal of promoting their professional development.

Research purpose and research questions

In light of the need to explore foreign language teacher agency for research and their experiences in funding applications, this study attempts to unveil foreign language teacher agency for research in NSSFC applications from a CDST perspective. Based on the view of teacher agency for research as complex systems, the following research questions are proposed:

-

1.

What are the key constituents of the system of university foreign language teacher agency for research in their funding applications?

-

2.

How do university foreign language teachers exercise their agency for research in funding applications in a dynamic way?

Methods

A qualitative case study is an intensive, holistic description, and analysis of a single entity, phenomenon, or social unit; it is “particularistic, descriptive, and heuristic” and relies heavily on inductive reasoning when handling multiple data sources (Merriam 1998, p. 16). According to Yin (2003), a case study investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context. In this study, we aimed to attain a holistic understanding of university foreign language teachers’ funding application experiences through the collection of multiple sources of information or perspectives on observations and an in-depth analysis of the data; thus, a qualitative case study (Huberman and Miles 2002) was used to facilitate in-depth examination of the participants’ agency enactment.

Research context

The site of this inquiry, i.e., H University (HU), is in East China and is a comprehensive university under the construction of the country’s “First-Class Discipline” (“一流学科”). Furthermore, it is a member university of “Project 211” (“211工程”). On the one hand, the foreign language faculty of HU enjoys a good reputation in the region, although it has also experienced a weakening status and been confronted with disciplinary repositioning and adjustment due to the increased weight placed upon the “hard sciences” by the country and the university. On the other hand, the geographical location of HU and the researchers’ social networks facilitated ample data collection.

Participants

Purposeful sampling was used as a criterion to recruit appropriate participants for this study. In recent years, the number of NSSFC projects approved has witnessed steady growth at the foreign language faculty of HU. We recruited in-service teachers from the foreign language faculty of HU, who had or had been approved for an NSSFC project or NSSFC projects. Although the number of NSSFC applicants is much greater than the number of “winning bidders”, we consider only these winners because they are more likely to share the “best” solutions in funding applications. Finally, 12 teachers were invited to participate in this study (with pseudonyms and demographic information presented in Table 2). Due to the fact that some teachers successfully won a bid for an NSSFC project after they had completed a previous NSSFC project, there are 16 approved NSSFC projects in this study, among which half were general projects, followed by five youth projects and three projects involving the foreign translation of a Chinese academic work, which is a relatively new addition to the NSSFC lineup (Fig. 1). The discipline category of the approved NSSFC mainly includes foreign literature, linguistics, and other language-related disciplines, such as Chinese literature and archaeology (Fig. 2). Four teachers at the faculty had won bids for the NSSFC projects twice; most of them initially succeeded in a bid for a youth project and then won a bid for a general project. The 12 participants consisted of five female teachers and seven male teachers. The average age of the participants at the time of the study was 49 years old, and the average age when the participants were granted by the NSSFC was 42 years old. When receiving approval from the NSSFC, 56% of these teachers were associate professors, 25% were lecturers, and 19% were professors (Fig. 3); at the time of this study, half of the teachers were professors and half were associate professors Footnote 3 (Fig. 4).

Data collection

Narrative frames and semi-structured interviews were adopted as the main instruments of data collection; these interviews commenced in August 2021 and concluded in December 2021. According to Barkhuizen and Wette (2008), narrative frames are useful for collecting a large amount of data from a large number of participants, providing a means of entry into an unfamiliar research context. Narrative frames provide guidance and support in terms of both the structure and the content of what is to be written. By using sentence starters as clues, participants can easily refer to their lived experiences in a logical sequence. In this study, we created narrative frames based on the two research questions and performed a pilot study among a small group of teachers. We revised the structure, template, and sentence starters several times to ensure that the participants could complete the frames conveniently and efficiently. The narrative frames in this study included the following themes: beliefs and attitudes about the NSSFC, the process of the NSSFC application, the intentional efforts made to apply for the NSSFC funding, resources or constraints encountered during the application process, and emotions before and after the NSSFC applications. Notwithstanding the merits of narrative frames, this approach has its own flaws, as mentioned by Barkhuizen and Wette (2008, p.382): “The narrative frames tend to depersonalize the teachers’ stories of experience”. To compensate for the homogenization of narrative frames, semi-structured interviews were conducted during the follow-up data collection.

After collecting the narrative frames provided by the 12 teachers, we read through the stories they recounted regarding their funding applications to gain an initial understanding. Based on the narrative frames and rounds of pilot interviews with accessible teachers, we selected Teacher Zhao, Teacher Cheng, and Teacher Ye (all pseudonyms). The reasons for the elicitation were twofold. First, they varied in terms of their professional titles and their research areas as well as in the category of funding they received from the NSSFC; second, all these teachers represented information-rich cases (Patton 2002), and their stories maximally illustrated the intricacies and dynamics of their funding application process, which made further exploration both valuable and possible.

Interviews were conducted to substantiate and clarify the narrative frames. The interviews were semi-structured (Kvale and Brinkmann 2009). Both the researcher and the interviewers were free to construct a conversation; however, at the same time, the focus was maintained on a particular predetermined research topic. An interview guide was used in each conversation. Two rounds of interviews were conducted with the three participants. The first-round interviews revolved around the manifestation of their agency in the NSSFC applications, and the second-round interviews explored the dynamic process of their agency in funding applications. We divided the interview sessions into two rounds because an initial analysis of the first-round interviews was needed before more questions could be raised during the second-round interviews. The intervals between the two rounds of interviews varied (from 2 weeks to 4 weeks) depending on the interviewees’ availability. It is believed that such an interval is neither too short (thus making the initial analysis impossible) nor too long (thus making the participants easily forget the interview topics) for this study. Each interview lasted for approximately 1–1.5 h (the overall duration of the interviews was 8 h), and all the interviews were recorded with the permission of the participants.

Documents are important sources of data analysis and can take a variety of forms. They can be used for “systematic evaluation as part of a study” and can provide “background and context, additional questions to be asked, supplementary data, a means of tracking change and development, and verification of findings from other data sources” (Bowen 2009, p.30-31). In this study, some of the participants’ NSSFC application files served as significant sources of inquiry and analysis. Before the interviews, the first author read the participants’ application files several times to identify the research topic and how the participants had written the grant proposal logically and coherently, as well as how the application files were revised based on earlier drafts. According to Nadin and Cassell (2006, p.216), the notion of a research diary “was grounded in the epistemological position of social constructionism and the need for reflexivity in research”. In this study, the first author kept detailed notes regarding her reflections during the data collection, the data analysis, and the possible influences of her own experience as a researcher in a foreign language discipline.

Data analysis

In accordance with the nature and objective of the study, thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006) was adopted to analyze the data. First, the researchers transcribed the interviews verbatim and integrated them with the narrative frames, thereby obtaining a rich dataset (as transcribed, 97 pages: A4, single-paged). Second, the researchers coded, categorized, synthesized, and theorized the words (Saldaña 2009): 1) a Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis (CAQDA) tool, namely, ATLAS.ti (9 Desktop), was used to import the text; the researchers read the text several times in this format. 2) By assigning small segments of textual data to the emerging codes, the researchers identified broader themes that enabled them to reconstruct and retell the participants’ stories. 3) After the software-assisted coding process, the researchers recoded the data manually because reading the material on screen or in print might generate different insights. 4) The researchers compared the two sets of codes generated using both methods and integrated overlapping themes (Table 3).

The process produced 92 open codes, which were further organized under five broader themes, namely, teachers’ agency beliefs, teachers’ agency practice, teachers’ agency emotions, teacher agency for research as spatially and temporally situated, and teacher agency for research as relational (Table 4).

Trustworthiness and ethical considerations

Different measures were adopted to enhance the trustworthiness of the study. Two researchers coded the transcribed data individually to ensure intercoder reliability. To ensure the reliability of the coding scheme, two coders randomly selected a Word document in the dataset to code before commencing the real coding, and the weighted value of the kappa of the inter-coder reliability test was 0.873 (higher than the accepted standard of 0.75). The first author and the second author then worked independently to examine and code the transcribed texts while bearing the two research questions in mind. When no consensus could be reached, an additional coder was asked to decide on the label (category); a member-check was also conducted when the coding results were returned to the participants to ensure that the researchers understood their articulated agency in an appropriate way.

Since the first author collected data from her own workplace, her position can be both a resource and a limitation. First, her position allowed lasting engagement and persistent interactions, which entailed familiarity with the research context and the topic. However, the researcher’s insider status can also pose risks in which her prior interpretations may guide the analysis. In this study, potential biases were mitigated through the first author’s research diary and constant exchanges with the second author. The third author contributed to the theoretical and conceptual aspects of the study.

Ethical issues had to be considered throughout the research process (Taylor 2001). In this study, we were committed to maintaining an ethical relationship with the participants, which is manifested in the following dimensions. All of the participants signed an informed consent form; all of the interviews were recorded with the participants’ permission; access to the data was limited to the researchers only; a pseudonym was given to each participant so that the data would not reveal any of the participants’ personal or organizational information; to ensure the anonymity of the participants, the data were analyzed on a cross-case basis, which means that the analysis focused on collective and shared meanings across the whole dataset and not, for example, on individual narratives.

Findings

This section presents accounts of foreign language teachers and their experiences with NSSFC applications to illustrate teacher agency for research in funding applications from a CDST perspective. It provides a localized account of the constituents of teacher agency for research as a complex system, and it also highlights the dynamics of how these constituents impact each other to view teacher agency for research as a social, relational, dialogic, and contexutal entity. The findings of this study are as follows: 1) there are subsystems of teacher agency for research in funding applications, i.e., agency beliefs, agency practice, and agency emotions; and 2) the developmental paths of teacher agency for research are situated and relational.

Research question one: The key constituents of the system of university foreign language teacher agency for research in funding applications

The participants’ agency for research as a complex system was found to consist of three key subsystems (beliefs, practice, and emotions). Furthermore, each subsystem has its own subsystems.

Persistent beliefs: Going to the NSSFC “national team”

In general, the participants exhibited unwavering beliefs in the NSSFC as well as in the application of it. To them, the NSSFC represents the national level, the “highest” echelon of funding in their career paths.

In my eyes, the NSSFC represents the most frontier research area (Teacher Cao-NF-22)Footnote 4; it represents the highest rank (of projects) in the country’s Humanity and Social Science research (Qu-NF-15).

In addition to recognizing the authoritativeness of the NSSFC, teachers expressed trust in the fairness of the recruitment process for NSSFC projects.

The NSSFC represents fairness, and all applicants, regardless of their background, have an opportunity to win the projects if their research proposal is well written (Zhao-NF-20).

In addition, teachers regard earning an NSSFC project as conveying a sense of honor.

Getting funded by the NSSFC is a supreme honor and a highlight moment in one’s career (Wei-NF-15).

In summary, the participants’ consensus regarding their agency beliefs about the NSSFC, i.e., authoritativeness, fairness, and a sense of honor, represented a prerequisite for their success(es) in the application.

The sustaining practices with grit: Unremitting efforts made throughout the application

Our data indicate that teachers’ NSSFC applications were manifested in their resolution and preparation before the application, their constant modifications of the grant proposals, and their reflections after the application.

First, according to most participants, they started to become aware of the NSSFC during their doctoral studies, with motivations ranging from external factors such as professional title appraisal to internal factors such as pursuing new heights in one’s academic career.

It is a good way to push myself to do research, also, it is due to the need for professional title appraisal, the performance assessment, and the qualifications to become a postgraduate supervisor (Xue-NF-16); it is because of my academic pursuit (Zhen-NF-16); because I want to learn by trying (Cheng-NF-19).

Second, the participants made adequate preparations for the NSSFC application, such as reading the literature, studying the application guideFootnote 5, and selecting a research topic.

Teacher Zhao assumed that reading literature should be a regular practice. Both academic monographs and journal articles were included in his reading list.

Reading monographs can help you understand the developmental trajectories of a research topic; however, reading high-quality journal articles (peer-reviewed articles written in English and the CSSCIFootnote 6 journal articles) is also indispensable and can help you identify the most cutting-edge research (Zhao-Int-63).

Teacher Cheng described taking notes during literature reading as a good habit.

The palest ink is better than the best memory. My experience is taking notes. For some important literature, we need to study it carefully, take notes, and write summaries. For literature that is not so relevant to my study, I highlight some key words in the PDF and then write them down in the notebook (Cheng-Int-97).

Teacher Ye claimed that it is equally important to read literature in one’s own research field and to read literature in other related fields.

In recent climates, many approved projects have shown an interdisciplinary tendency. There are many fields related to foreign language studies, such as psychology, sociology, and educational sciences. In the future, computer science, brain science, and artificial intelligence are expected to become more integrated with foreign language studies. Sometimes it is difficult to read them; we could start with easy ones (Ye-Int-132)

Aside from reading the literature, most participants emphasized having a close examination of the application guide, as well as the project approval data in recent years so as to identify hot spots and analyze the difficulty of applying for each category of project.

I paid attention to the project approval data and the application guide, which is directional and can help me understand the research trend and formulate my title (Yan-NF-46); they not only represent policy orientation but also reflect academic trends (Qu-NF-37).

Teacher Zhao, who successfully won a bid for NSSFC funding twice, believed that heightened attention has to be paid to the minor changes made in the application guide compared to the previous year.

I usually compare the changes and adaptations made to the application guide over the past two or three years because these changes, I believe, are usually the areas that the country hopes the researchers will focus on (Zhao-Int-95).

Many teachers admitted that conflicts typically occurred between one’s own research interests and the research hotspots and that it was critical to address this complicated relationship.

I believe that the relationship between doing what I am good at and seeking research hotspots is to find the nexus. Linking theory with practice is a good way (Wei-NF-42); I think the two are negotiable. I address this relationship by prioritizing the needs of our country’s development (Su-NF-48); the relationship between the two exhibits duality, i.e., making hot topics the core and taking my research direction as the carrier (Xue-NF-48); and I evaluate my competence properly to balance the two (Cheng-NF-48).

In addition, many teachers claimed that it was harmful to follow the research trends blindly while abandoning one’s own research area.

Being “self-centered” is the foremost principle when selecting a topic. It is not practical to follow the application guide each year, which can lead to discontinuity in personal academic development. The topic I selected is based on my Ph.D. dissertation, which has made me confident in writing the proposal. Plus, I have previous research achievements on that (Ye-Int-187).

In line with the aspects mentioned above, the participants also focused on the different stages of writing a grant proposal, namely, writing it up-revising-finalizing-submitting. Among the 12 teachers, 10 indicated that they had spent 1–3 months writing the proposal, one had spent half a year, and one had spent a year and a half. All the teachers addressed the logic and integrity of the argumentation.

The most essential thing to include in the proposal is logical argumentation and putting it in a simple but profound way (Qu-NF-26); the most important are research questions, research methods and research value (Zhao-NF-19; Cheng-Int-76). The most challenging parts of the proposal are the literature review (Cao-NF-34; Gao-NF-34), the research methods (Cheng-NF-42), the research content (Yan-NF-40; Cui-NF-37), and the sample chapter for the project involving the foreign translation of a Chinese academic work (Su-NF-32).

Some teachers emphasized the differences between journal article writing and grant proposal writing, although the two share similarities regarding their academic nature and rigor.

When I earned my Ph.D., I had no experience with the project application. The first few failures in the funding application could be attributed to the style of my writing, which is similar to writing a research paper (actually writing a proposal is different from that) (Ye-Int-158).

A research proposal is a highly condensed journal article because an article usually contains approximately 10,000 words, while the body part of a proposal should be less than 7000 words. The research article discusses the research that was conducted, emphasizing the results and discussion. A research proposal is different by telling the reviewers what the value of your research is, how you are going to conduct it, and most importantly, persuading them to approve this project (Cheng-Int-118).

Revising and submitting the proposal are also important to the participants. Almost all the participants mentioned the importance of language and format, which were easily ignored.

If there are too many wrongly written characters and awkward expressions in the proposal, it can be revealed that the applicant is not as precise in his or her academic research. Needless to say, the reviewers will be unlikely to grant these (careless) applicants (Yan-NF-43).

The word size selected for the proposal must be appropriate (neither too big nor too small). It could be in 12-point font. The line spacing could be 18 or 20. Use the Song typeface for the Chinese characters, and the Times New Roman for the English words. It is also possible to highlight certain key points by using bold font. The typesetting should be neat and reader friendly. When I was applying for my second NSSFC project, I found a punctuation mistake at the last minute before the submission. I took back the proposal, corrected the mistake, and reprinted it (Zhao-Int-201).

A factor of equal importance is the reflectivity observed in the teachers, which enabled their application experiences for an NSSFC project to be transferable to other projects in the future. They moved back and forth between their practice and reflection and speculated about the lessons they had learned during the application process.

The first time I started to write my NSSFC application was only two weeks before the submission deadline. You can imagine the hurry and haste in it. Undoubtedly, my first attempt failed. After that, I realized that everything should be done beforehand. Therefore, I began to write the application during the summer vacation, so that I had adequate time for revision and proofreading. I talked at length with those who have succeeded, and indeed, their experience had many implications for me. Yes, prepare as early as possible, that is, (Zhao-Int-371).

The coexistence of contradictory positive and negative emotions: Getting to fight or flight

Embedded in meaningful social relationships, the participants’ feelings and emotions composed an integral part of their professional development, which differed before and after they applied for the NSSFC funding (Table 5). Both negative emotions such as anxiety, strain, agony, and desperation and positive emotions such as confidence, joy, happiness, and hope emerged during the funding applications. Some teachers also exhibited attitudes of trying and calmness before and after the application.

From getting to know the NSSFC and starting to prepare for it to successfully getting the bid, my psychological state changed a lot. In the beginning, I was “foolish and bold”, failing to realize the difficulty of the application. When my application was approved, I felt full of confidence. Then, anxiety about how to complete the project on time arose (Qu-NF-18); my emotions changed from trying to being more confident (Cao-NF-18) and from anxiety about waiting for the results (of the approval list) to feelings of happiness (Zhen-NF-17).

The teachers also emphasized the positive impact of negative emotions, which can be powerful forces for transformative actions. According to the teachers, the struggle with negative emotions was painful but important during the application process.

When I feel anxious or full of tension, I often choose to make concrete plans in my academic work. The only way to fight anxiety is by being concrete (Ye-Int-205).

All the data seem to suggest that the participants expressed their positive emotions after receiving the NSSFC funding, for instance, confidence, delight, and pride, all of which, according to them, become further impetus for them to fulfill their research objectives of the NSSFC and even to submit applications for other forms of funding at the school level, the provincial level, or the national level.

Research question two: the dynamics of teacher agency for research in funding applications

Our data indicate that teachers’ agency is a complex dynamic entity that is not only temporally situated but also relational in the sociocultural context.

The past, present, and future dimensions of agency: Rome is not built in one day

First, participants emphasized the importance of accumulating expediences in previous successful funding applications. Factors such as research competence, literature reading, experiences in paper writing, research projects, visiting studies, translation competence, and contacting a publication company (for projects involving the foreign translation of a Chinese academic work) were deemed critical.

I think that academic experiences in the early stages—for instance, research conducted during my Ph.D. and published journal articles (Wei-NF-37); a focus on literature reading and other funding (Zhao-NF-42); previous experiences in applying for NSSFC funding; good proficiency in the target language of foreign translation of a Chinese academic work; experience in cross-cultural communication (Su-NF-43); one year of visiting study abroad, having published an English article and an English monograph (Zhen-NF-20); and contact with a publishing company overseas (Xue-NF-60)—are important during the preparation stage.

Second, teachers highlighted the need for a sound judgment of the present, including the establishment of a knowledge network through literature reading, appropriateness of the research methods, theoretical altitude in the grant proposal, clarity of the research framework, attention to the word limit, careful selection of the research team, and reasonability of the project budget.

When listing the applicants’ previous academic achievement in the proposal, it should be noted that the listed items are related to the research proposed (Yan-NF-55); that the listed items were published in authoritative journals and were published in the past 5 years (Xue-NF-44); that the members of the research team listed should be considered well in terms of variation in their professional titles, educational backgrounds, and age (Zhen-NF-44); that the academic backgrounds of the members listed should be considered (Cao-NF-43); and that the members listed should be from different age groups and can include international scholars, if necessary (Wei-NF-41).

Finally, the participants pointed to the fact that their agency for research in funding applications is future-oriented, i.e. their attention given to the country’s policies and strategic needs, their evaluation of the research trends, their personal research interests, and future academic planning. Notably, the participants often reflected on their evaluation criteria when they were invited to peer review a grant proposal as a project manager of the NSSFC.

Enhancing my “national identity” can help determine the research trend and increase the possibility of success (in the application) (Su-NF-65).

Through reading the literature, I can have a widened and deepened understanding of the field under study, while working on this research project, I have the privilege of getting to know different scholars, which can help establish research communities. My experience is that it is necessary to follow the research schedule step by step to work on the research project smoothly (Xue-NF-62).

As an anonymous reviewer, I attach great significance to the originality of the topic, the adequateness of the argumentation, and the appropriateness of the research methods (to be applied) (Yan-NF-61).

Ongoing interactions between the individual and the environment: No one is an island

Our research findings identified numerous factors affecting teacher agency for research in the case of funding applications. The synergy of personal competence, character, and behavior was crucial in exercising agency for research. The participants of our study emphasized the significance of self-control, self-supervision, and time management.

As a teacher-researcher, I am strict with myself. Time is even limited when you have a child to look after (Cui-NF-54); I conduct time management by making use of the winter vacation and summer vacation, the weekend, and staying up late (Zhao-NF-47); through increased investment of time, improved working efficiency, and applying for an academic leave (Xue-NF-48).

Teacher Ye mentioned in his interview that “being free of distractions” is key to academic engagement and that constructing a relatively undisturbed space is rather important.

Given that the distance between school and home is relatively short, I spent time reading at school during holidays and festivals, which can free me from disturbances. In recent years, I have taken on some administrative work in the faculty, and I must redistribute my time. Making use of time fragments is a good way, and getting up early is also efficient (Ye-Int-238).

On the other hand, the participants attached great significance to environmental factors, including the influence of significant others, support from the faculty and the school, and the impact of the overall academic atmosphere.

I learned experiences in research topic selection and argumentation in the proposal from my colleagues and my peer Ph.D. classmates (Xue-NF-50); when I attend many academic conferences, I have opportunities to meet many researchers with shared research interests, from whom I can obtain valuable new thoughts (Zhao-NF-57); I learned how to express with theoretical altitude from retired (senior) teachers (Su-NF-50); I learned from my supervisor the way of thinking in the research field (Cao-NF-48; Wei-NF-43).

The faculty encourages the applicants to report and listen to the experts’ suggestions; the university also invites experienced experts (from disciplines other than foreign languages) to read and give feedback on the proposal. This approach is helpful because I cannot detect some problems by myself (Cheng-Int-248).

When reading the written material, such as the participants’ earlier drafts of the grant proposal, we found that there were 19 different versions ranging from the very first draft to the finalization of Teacher Zhao’s proposal. In each draft, the changes had been highlighted. Zhao recounted his experience as follows:

Collect as many successful research proposals as possible. For instance, in the book titled 300 Questions in Funding Applications in Humanity and Social Sciences, there are many successful cases of the proposal. If your colleagues or peers are willing to share their research proposal, that would be nice. The other thing is to keep on revising. First, you revise yourself; then, you ask other people to revise. One of the most impressive things is that each year, the experts from the faculty and the school would help by providing suggestions on the format, language, and argumentation of the proposal (Zhao-Int-132).

In the interview, Teacher Ye mentioned the push toward an enhanced academic atmosphere within the faculty:

Our colleagues show increased enthusiasm for research, which represents peer pressure on me. We have an online chat group where we can seek professional literature retrieval services. Many colleagues seek help, especially during holidays and festivals. Seeing their diligence, I am motivated (Ye-Int-205).

The teachers also claimed that they had experienced structural constraints that hindered their enactment of agency for research, such as the lack of a real research community, the weakened disciplinary status of foreign languages in the country, and the marginalization of foreign language studies at the university.

There are not always favorable conditions for us. The so-called research community is a castle in the air, which does not exist. We have a considerable heavy teaching load, which leaves us little time to communicate with other colleagues. Plus, many of us are in a competitive relationship, which means we cannot cooperate (Cui-NF-60).

In recent years, there have been fewer opportunities, i.e., suggested topics for foreign language researchers in the application guide, because of the weakened disciplinary status of foreign languages in the country (Zhen-NF-98).

The university put forth great efforts in its “first-class” discipline. Traditional humanistic disciplines such as foreign language studies face fewer resources. We have no advantages on the university scale (Zhao-Int-211).

Both personal factors and environmental factors related to teacher agency for research were scrutinized in this section, proving that agency is a dynamic and relational entity.

Discussion

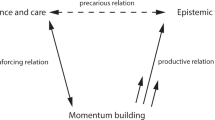

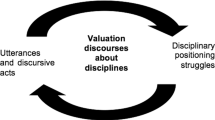

This study probes into the funding application experiences of foreign language teachers at H University in China, examining and interpreting the manifestations and the dynamic processes of teacher agency for research. The research reveals the following key findings: 1) Teacher agency for research complex system consists of subsystems of their agency beliefs, agency practice, and agency emotions; there are also interrelated subsystems in each subsystems; 2) Their agency for research is not only a situated but also a relational entity with dynamic features, which covers the past-present-future triad of agency, as well as the combined influence of personal and environmental factors. In this regard, we propose a conceptual framework to link the findings of the current study to relevant theories about agency and CDST (Fig. 5) as well as a data-driven pathway for university foreign language teachers exercising agency for research in funding applications which could potentially help other stakeholders in a practical sense (Fig. 6).

As schematized in Fig. 5, our study finds that teacher agency for research is manifested in interrelated subsystems, such as agency beliefs, agency practice, and agency emotions, where agency beliefs serve as the preconditions, agency practice as the transformative force, and agency emotions as a powerful mediation to bridge the gap between beliefs and practice. The interplay of the three subsystems elucidates why some people are more inclined to take agentic actions. At the individual level, university foreign language teacher agency for research is the result of their lived experiences and professional experiences, the decisions made on how to act based on the practical evaluation of reality, and the projection of both short-term and long-term academic planning. In addition, both personal and sociostructural dimensions contribute to the practice of university foreign language teacher agency for research. These illustrations illuminate the internal mechanism of teacher agency for research. The arrows shown in the figure demonstrate the dynamic interplay among the three subsystems, the situatedness within the past-present-future triad, and the reciprocal roles of personal factors and environmental factors.

Figure 6 offers a practical guide for funding applications based on the conceptual framework of this study. Given the interrelated subsystems and the ongoing dynamics of teacher agency for research, we suggest the following: first, teachers can establish positive recognition of funding applications, build self-confidence, and maintain a sense of worth in the application process; second, they are encouraged to make efficient and practical attempts throughout the different stages of funding applications, i.e., emphasizing personal planning, research methods, literature reading, and critical thinking, combining personal research interests with the application guide, learning and reflecting regularly; and last, they may have an appropriate evaluation of the influencing factors of teacher agency for research. On the one hand, teachers are supposed to foster their strengths while circumvent their weaknesses in research through a sensible evaluation of themselves; on the other hand, they are suggested to hone their writing competence and enhance their research skills by listening, expressing, and collaborating.

In light of the illustrations presented above, teacher agency for research consists of three key subsystems (agency beliefs, agency practice, and agency emotions). The three subsystems of teacher agency for research epitomize not only the beliefs and confidence that teachers have but also the choices they make, the actions taken, and the context which affords or restricts them during the enactment of agency.

Furthermore, each subsystem encompasses interrelated subsystems. For instance, their agency beliefs shape their understanding of the NSSFC, such as the authoritativeness of the funding, the fairness of the funding, and a sense of honor while being granted, which corresponds to Zhou’s (2015) claim that the NSSFC plays a leading role in promoting philosophy and social sciences in China and is considered authoritative, fair, and pioneering.

Teachers’ agency practice can be further conceptualized as the subsystems of motivation, preparation, acting, and reflecting. Foreign language teachers exhibit integrated motivation for academic pursuits and professional promotions, and they invest tremendous efforts in different stages of funding applications. Our case highlights that literature reading, critical thinking, a close examination of the application guide and the project approval data, and establishing a balance between personal research interests and the research hotspots represent the preliminary preparations for the application. When writing a grant proposal, posing manageable and focused research questions is requisite (Zheng and Ruan 2018), and noting adequate argumentation and its internal relationship, being reader friendly, and addressing language and format are also crucial. These findings resonate with Wen and Lin’s (2017, p.26) assumption that anonymous reviewers attach significance to “the adequacy of literature review, the preciseness of research design, the use of academic language, and the appropriateness of the topic selected”.

University foreign language teachers’ agency emotions are multifaceted, encompassing both positive and negative aspects, which reveals that research is a major concern for their professional lives and thus drives teachers to experience varied emotions (Gu and Gu 2019). The emergence of certain agency emotions can help individuals find solutions in the face of problems. Positive emotions such as joy and satisfaction are revealed to be important in the enactment of teacher agency for research, while negative emotions (e.g., dissatisfaction, distress, and anxiety) in particular seem to be powerful forces that lead to transformative actions in terms of “making a change in one’s career or influencing work and organizational practices” (Hökkä et al. 2017, p.177).

Overall, the three subsystems of university foreign language teacher agency for research have explained why some teachers are more proactive than others in taking initiative, making choices, bringing about changes, and fostering new relationships in their research engagement, especially funding applications. Our findings partly conform to Goller and Harteis (2017) three facets of agency (i.e., agency beliefs, agency competence, and agency personality) in that there are always beliefs and practices pertaining to teachers’ professional development. However, our study claims that the subsystems of agency practice and agency emotions are more dynamic and prone to change than agency competence and agency personality according to Goller and Harteis’s claim. Their agency beliefs, defined as teachers’ subjective assumptions about research engagement and funding applications in this study, serve as the prerequisite; their agency practice, defined as a series of meaning-making efforts during the funding application process, serves as the fundamental procedure to translate their rhetoric into reality; and agency emotions, defined as teachers’ strong feelings manifested during the application process, serve as the mediating force that bridges the gap between beliefs and practice.

This study underscores the situated nature of teacher agency for research, which concurs with Emirbayer and Mische’s (1998) proposal that agency is generated from a teacher’s own way of reconstructing the personal past experiences and intentions of the future to deal with a present situation. The teachers in our study engaged in internal dialogues with their own past experiences and future goals and plans to capture the present situation. Just as a complex system can achieve temporary stability through its self-organizing attractors, agentic acts can achieve stability through the interplay between agency and structure (Larson-Freeman 2019). As Mercer (2012) notes, viewing agency as a whole system implies considering it temporally situated, connecting a person’s life history, multifarious experiences, and future goals, expectations, and imaginations. Complementing previous findings that there are features of situated adaptivity, interconnectedness and interdependency, dialogic feedback, positioning, and critical incidents in language teachers’ agency systems (Hiver and Whitehead 2018; Rostami and Yousefi 2020; Qi and Wang 2022), our study further reveals that analyzing teacher agency for research in funding applications should be built upon teachers’ past research and professional experiences, a reasonable judgment of their research competence, and a clear vision for their future academic career.

In line with previous research findings indicating that teachers’ academic practice and agency for research are related to their personal values (e.g., motivational strategies) as well as various external factors (Yuan 2021; Nakata et al. 2021), our findings cogently elaborate a constant interplay between various factors when exercising their agency for research in funding applications; thus, agency is relational, which echoes Kayi-Aydar’s (2019) ecological view of language teacher agency. According to Ellis (2019), agency is defined in terms of the systematic relationship between the organism and its environment and thus is always related to affordances or restrictions in the context. First, receiving research funding is the result of teachers’ personal competence, emotional attitudes, and behavioral strategies; second, teacher agency cannot be realized without the concerted efforts of personal factors and environmental factors, such as peer communication, expert guidance, faculty support, and the influence of a positive research atmosphere. It is worth nothing that the teachers in this study also mentioned the restrictive conditions faced by foreign language researchers, proving that agency entails not only the determination to do but also the choice of not doing. Teachers, as agents of research, are supposed to cultivate the capacity to harness both personal resources and environmental affordances to cope with challenges.

Conclusion

In this study, we scrutinized how 12 foreign language teachers from a university in China exercised their agency for research in funding applications through narrative frames and in-depth interviews. We delineated the interactive subsystems of their agency for research as well as the situated and relational features of their agency for research. Based on the findings of the study, we propose the following suggestions to promote foreign language teachers’ well-being and professionalism in the context of funding applications: 1) buttressing confidence in research, fostering positive emotions in research, and bridging the gap between rhetoric and reality through personal endeavors; 2) prioritizing literature reading, topic selection, meticulous writing of the proposal, and persistence in applying; and 3) increasing academic interactions by listening to suggestions from peers and experts, for instance, joining a research community or a professional learning community for both collegial and institutional support.

This study has advanced our understanding of teacher agency in funding applications in the unique context of tertiary foreign language education in China, expanded the application of CDST, and offered a conceptual framework as well as practical suggestions regarding foreign language teacher agency for research. Notwithstanding its contributions, the findings were developed only from the analysis of a small number of cases at a Chinese university due to the exploratory nature of this research and the limited time and resources available. Future studies call for a closer examination of the applicability of the frameworks proposed in this study to other contexts in combination with a longitudinal research design to form a more complete picture of foreign language teachers’ quandaries and vicissitudes of professional learning in a dynamic and complex milieu of educational development.

Data availability

The data supporting the results of this study are available in the supplementary files.

Notes

In the 20th National Congress of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) (‘二十大’), it was pointed out that China’s economic development has entered a new phase, which is characterized by an economic shift from rapid growth to “high-quality development”. Pursuing the high-quality development of higher education is one of the strategic goals for both the present and the future.

Project 211 is the Chinese government’s endeavor aimed at strengthening approximately 100 institutions of higher education and key disciplinary areas as a national priority for the 21st century. There are 112 universities in the project 211. Project 985 is a constructive project for founding world-class universities in the 21st century conducted by the government of the People’s Republic of China on May 4, 1998. The second phase, launched in 2004, expanded the program until it has now reached 39 universities.

At H University, obtaining the national-level funding is a requirement for the professional promotion of either an associate professor or a full professor.

This quotation refers to the 22nd line of Teacher Cao’s narrative frame. We use the abbreviation “Int” to refer to the interview in the following quotations.

When the National Office for Philosophy and Social Sciences make the application announcement each year, an ‘application guide’ (‘课题指南’) is also attached to the announcement, which clarifies the general requirements for the applicants and a detailed list of the topics suggested for different disciplines.

Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index (CSSCI) is an interdisciplinary citation index program in China, which covers approximately 500 Chinese academic journals in the humanities and social sciences. At present, many leading Chinese universities and institutes use CSSCI as a basis for evaluating candidates for academic achievements and promotions.

References

Adamson, B (2004). China’s English: A history of English in Chinese education. Hong Kong University Press

Ahearn LM (2001) Language and agency. Annu Rev Anthropol 30:109–137. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.30.1.109

Backlund A (2000) The definition of system. Kybernetes 29(4):444–451. https://doi.org/10.1108/03684920010322055

Bandura A (2001) Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol 52(1):1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

Bandura A (2006) Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspect Psycholog Sci 1(2):164–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00011

Bao J, Feng D (2022) “Doing research is not beyond my reach”: The reconstruction of College English teachers’ professional identities through a domestic visiting program. Teach Teach Educ 112:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103648

Bao J, Feng D (2023) When teaching and research are misaligned: unraveling a university EFL teacher’s identity tensions and renegotiations. System 118:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044325

Biesta G, Priestley M, Robinson S (2015) The role of beliefs in teacher’s agency. Teachers and Teaching 21:700–719. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044325

Bowen G (2009) Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual Res J 9(2):27–40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Buhrman T, Di Paolo E (2017) The sense of agency-A phenomenological consequence of enacting sensorimotor schemes. Phenomenol Cogn Sci 16:207–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-015-9446-7

Barkhuizen G, Wette R (2008) Narrative frames for investigating the experiences of language teachers. System 36(3):372–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2008.02.002

Chen H (2023) A lexical network approach to second language development. Hum Soc Sci Commun 10:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02151-6

Chu Z (2021) The importance of NSSFC lies in its directiveness. Social Sciences in China A08

Dai W (2009) Review and prospect of 60-year foreign language education in China. Foreign Lang China 6:10–15

Ekşi CY, Yakışık BY, Aşık A, Fişne FN, Werbińska D, Cavalheiro L (2019) Language teacher trainees’ sense of professional agency in practicum: Cases from Turkey, Portugal and Poland. Teach Teach 25(3):279–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2019.1587404

Ellis NC (2019) Essentials of a theory of language cognition. Mod Lang J 103:39–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12532

Emirbayer M, Mische A (1998) What is agency? Am J Sociol 103:962–1023. https://doi.org/10.1086/231294

Feryok A (2012) Activity theory and language teacher agency. Mod Lang J 96(1):95–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2012.01279.x

Gao X, Zheng Y (2018) Heavy mountains’ for Chinese humanities and social science academics in the quest for world-class universities. Compare 50(4):554–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2018.1538770

Goller M (2017) Human agency at work: An active approach towards expertise development. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-18286-1_2

Goller M, Harteis C (2017) Human agency at work: Towards a clarification and operationalization of the concept. In: Goller M, Paloniemi S (eds) Agency at work: An agentic perspective on professional learning and development. Springer International Publishing, p 85–103 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60943-0_5

Gu H, Gu P (2019) A case study on the research emotion adjustment strategies of university English teachers. J PLA Univ Foreign Lang 42(5):57–65

Hamann J (2016) The visible hand of research performance assessment. High Educ 72:761–779. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9974-7

Heikkilä M, Mankki V (2023) Teachers’ agency during the Covid-19 lockdown: a new materialist perspective. Pedagog, Cult Soc 31(5):989–1004. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2021.1984285

Hiver P, Al-Hoorie A (2016) A dynamic ensemble for second language research: putting complexity theory into practice. Mod Lang J 100:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12347

Hiver P, Whitehead GEK (2018) Sites of struggle: Classroom practice and the complex dynamic entanglement of language teacher agency and identity. System 79:70–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.04.015

Hökkä P, Eteläpelto A, Rasku-Puttonen H (2012) The professional agency of teacher educators amid academic discourses. J Educ Teach 38(1):83–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2012.643659

Hökkä P, Vähäsantanen K, Mahlakaarto S (2017) Teacher educators’ collective professional agency and identity-transforming marginality to strength. Teach Teach Educ 63:36–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.12.001

Holland JH (2006) Studying complex adaptive systems. J Syst Sci Complex 19(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11424-006-0001-z

Huberman, M, & Miles, MB (2002). The qualitative researcher’s companion. Sage Publications

Jiang Z, Wu Y, Tsung L (2020) National research funding for sustainable growth in translation studies as an academic discipline in China. Sustainability 12(18):1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187241

Kayi-Aydar, H (2019). Language teacher agency: Major theoretical considerations, conceptualizations and methodological choices. In H Kayi-Aydar, X Gao, ER Miller, M Varghese, G Vitanova. Theorizing and analyzing language teacher agency (pp. 10–21). Multilingual Matters

Kusters M, van der Rijst R, de Vetten A, Admiraal W (2023) University lecturers as change agents: How do they perceive their professional agency? Teach Teach Educ 127:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104097

Kvale, S, & Brinkmann, S (2009). Interviews. Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. Sage Publications

Lantolf, JP, & Thorne, SL (2006). Sociocultural theory and genesis of L2 development. Oxford University Press

Larsen-Freeman D (1997) Chaos/complexity sciences and second language acquisition. Appl Linguist 18(2):141–165. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/18.2.141

Larsen-Freeman D (2019) On language learner agency: a complex dynamic systems theory perspective. Mod Lang J 103:61–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12536

Laudel G (2005) Is external research funding a valid indicator for research performance? Res Eval 14(1):27–34. https://doi.org/10.3152/147154405781776300

Lei L, Liu D (2019) Research trends in applied linguistics from 2005 to 2016: A bibliometric analysis and its implications. Appl Linguist 40:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amy003

Li M, Wang W (2021) Problems of higher foreign language education in China: From the perspective of foreign language education studies. Foreign Lang Their Teach 1:21–28+144

Liu S, Chen Y, Shen Q, Gao X (2022) Sustainable professional development of German language teachers in China: research assessment and external research funding. Sustainability 14:1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169910

Liu Z, Zhu L (2018) The approval status and trends in NSSFC linguistics and literature disciplines (2013–2017). J Xi’ Int Stud Univ 4:19–24

Lu H, Yoon S (2022) “I have grown accustomed to being rejected”: EFL academics’ responses toward power relations in research practice. Front Psychol 13:1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.924333

McKinley J (2019) Evolving the TESOL teaching-research nexus. TESOL Q 53:875–884. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.509

Mercer S (2012) The complexity of learner agency. J Appl Lang Stud 6:41–59