Abstract

Dynamical processes on networks have generated widespread interest in recent years. The theory of pattern formation in reaction–diffusion systems defined on symmetric networks has often been investigated, due to its applications in a wide range of disciplines. Here we extend the theory to the case of directed networks, which are found in a number of different fields, such as neuroscience, computer networks and traffic systems. Owing to the structure of the network Laplacian, the dispersion relation has both real and imaginary parts, at variance with the case for a symmetric, undirected network. The homogeneous fixed point can become unstable due to the topology of the network, resulting in a new class of instabilities, which cannot be induced on undirected graphs. Results from a linear stability analysis allow the instability region to be analytically traced. Numerical simulations show travelling waves, or quasi-stationary patterns, depending on the characteristics of the underlying graph.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Self-organized structures can spontaneously emerge from a complex sea of microscopic, interacting constituents. This is a widespread observation in nature, now accepted as a paradigmatic concept in science, with many applications ranging from biology to physics. Hence, pinpointing key processes that yield macroscopically ordered patterns is a fascinating field of investigation, at the forefront of many exciting developments.

For example, the Turing instability1 constitutes a universal mechanism for the spontaneous generation of spatially organized patterns. It formally applies to a wide category of phenomena, which can be modelled via reaction–diffusion schemes2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. These mathematical models describe the coupled evolution of spatially distributed species, driven by microscopic reactions and freely diffusing in the embedding medium. Diffusion can potentially seed the instability by perturbing the homogeneous mean-field state, through an activator–inhibitor mechanism, resulting in the emergence of a patchy, spatially inhomogeneous, density distribution. Astonishing examples are found in morphogenesis, the branch of embryology devoted to investigating the development of patterns and forms in biology11. Moreover, spatial patterns of cortical activation observed with electroencephalography, magnetoencephalography and functional magnetic resonance imaging have been argued to originate from the spontaneous self-organization of interacting populations of excitatory and inhibitory neurons12. In this case, travelling waves can also develop following a symmetry breaking instability of a homogeneous fixed point13. The models are usually defined on a regular lattice or a continuous support, and the emphasis is placed on the form of the nonlinear interactions that are responsible for the instability.

For a large class of problems, including applications to neuroscience, the system under scrutiny is defined on a network rather than on a regular lattice. The seminal work of Othmer and Scriven14,15 provides a description of pattern formation on a network, which has been built on in subsequent years, in a number of different directions16,17,18. Particularly relevant to the work presented here is the article by Nakao and Mikhailov19, where the authors investigated the effects of complex graph structures on the emergence of Turing patterns in nonlinear diffusive systems, paving the way for novel discoveries in an area of widespread interest. The conditions for the deterministic instability are derived following a linear stability analysis, which requires expanding the perturbation on the complete basis formed by the eigenvectors of the discrete Laplacian. Travelling waves can also develop via an analogous mechanism20. To date, symmetric (undirected) networks have been considered in the literature. Again, the instability is driven by the non-trivial interplay between the nonlinearities, due to the reactions, and the diffusion terms. The topology of the space defines the relevant directions for the spreading of the perturbation, but cannot have an impact on the onset of the Turing instability. Consider, for instance, a reaction–diffusion system defined on a regular lattice and assume that it cannot experience a Turing-like instability: the system cannot be made unstable when placed on top of a symmetric network. In other words, the structure of the underlying graph cannot destabilize an otherwise stable scheme: the inherent ability of the model to self-organize in space and time is determined by the reaction terms. Here we refer to an instability arising from a local perturbation of a stable homogeneous fixed point. Different choices of the Laplacian, which allow for non-homogeneous fixed points, can yield generalized instabilities, as described in ref. 21.

In applications, however, networks are not always symmetric (‘undirected’). It is often the case that a connection between two nodes has a specific direction, which means that the resulting graph is directed. Think, for instance, of human mobility flow patterns with their consequences for transportation design and epidemic control. Several routes can be crossed in one direction only, thus losing the symmetry between pairs of nodes. The internet and the cyberworlds are also characterized by an asymmetric routing of the links. Traffic symmetry typically does not hold for network locations beyond intranet and access links22. The map of the neural connection in the brain is also asymmetric, due to the physiology of neurons23. This can be seen in connectome models24,25,26, coarse-grained maps of the brain, which reveal asymmetric arrangements of connections at different spatial scales.

Motivated by this observation, we show that topology-driven instabilities can develop for reaction–diffusion systems on directed graphs, even when the examined system cannot experience a Turing-like or wave instability if defined on a regular lattice. This is at odds with the behaviour of symmetric networks. Therefore, the characteristics of the spatial support that hosts the interacting species play a crucial role, often neglected in the literature. Consequently, our analysis represents a significant extension to the modelling of reaction–diffusion systems. The dynamical rules of interactions, on which the attention of the modellers has been so far solely devoted, are not the only instigators of the self-organized patterns seen in real-world applications. The topology of the space is also important and significantly influences the conditions that yield the dynamical instability. This novel perspective might also hint at the causes that seem to favour an evolutionary selection of network-like structures in the organization of living matter at different scales. For instance, the excitatory and inhibitory dynamics of neurons and their spatial arrangement are two ingredients that cannot be trivially decoupled, the first being probably optimized to serve the global functioning of the brain, given the peculiar structure of the second.

The paper is organized as follows. We start by discussing the mathematics of reaction–diffusion on a network, to provide some background for what is to follow. Next, we develop the generalized theory of pattern formation on a directed network. We test the theory, for specific models, for different choices of the underlying networks and employing two plausible definitions of the Laplacian operator. Travelling waves and stationary in homogeneous patterns are obtained by changing the topological characteristics of the graphs, while fixing the parameters to values for which the patterns cannot emerge when the model is defined on a symmetric spatial support.

Results

Background

We begin by considering a network made of Ω nodes and characterized by the Ω × Ω adjacency matrix W: the entry Wij is equal to one if nodes i and j (with i≠j) are connected, and it is zero otherwise. If the network is undirected, the matrix W is symmetric. Consider then two interacting species and label with (φi, ψi) their respective concentrations on node i. A general reaction–diffusion system defined on the network takes the form:

where Dφ and Dψ denote the diffusion coefficients of, respectively, species φ and ψ; f(·, ·) and g(·, ·) are nonlinear functions of the concentrations and stand for the reaction terms; Δij=Wij−kiδij is the network Laplacian, where ki refers to the connectivity of node i and δij is the Kronecker’s delta. Imagine now that system (1) admits a homogeneous fixed point, which we label (φ*, ψ*). This implies f(φ*, ψ*)=g(φ*, ψ*)=0. We also require that the fixed point is stable, namely that tr(J)=fφ+gψ<0 and det(J)=fφgψ−fψgφ>0, where J is the Jacobian of (1) evaluated at (φ*, ψ*) and fφ (resp. fψ) denotes the derivatives of f with respect to φ (resp. ψ), and similarly for gφ and gψ.

Patterns arise when (φ*, ψ*) becomes unstable with respect to inhomogeneous perturbations. To look for instabilities, one can introduce a small perturbation (δφi, δφi) to the fixed point and linearize around it. In doing so, one obtains equation (12) (see Methods). For regular lattices, the Fourier transform is usually employed to solve this linear system of equations. When the system is instead defined on a network, a different procedure needs to be followed19,20. To this end, we define the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the Laplacian operator:

When the network is undirected, the standard Laplacian is symmetric. Therefore, the eigenvalues Λ(α) are real and the eigenvectors υ(α) form an orthonormal basis. This condition needs to be relaxed when dealing with the more general setting of a directed graph, which we will discuss in the next subsection. The inhomogeneous perturbations δφi and δψi can be expanded as:

The constants cα and bα depend on the initial conditions. By inserting the above expressions in equation (12) (see Methods) one obtains the dispersion relation

which characterizes the response of the system in equation (1) to external perturbations. Here Jα is the modified Jacobian matrix, accounting for diffusion contributions. This quantity is defined in the Methods section.

We use (λα)Re and (λα)Im to label, respectively, the real and imaginary parts of λ(Λ(α)). If (λα)Re>0, the fixed point is unstable and the system exhibits a pattern whose spatial properties are encoded in Λ(α). These are the celebrated Turing patterns, stable non-homogeneous spatial motifs, which result from a resonant amplification of an initial perturbation of the homogeneous fixed point. The quantity Λ(α) is the analogue of the wavelength for a spatial pattern in a system defined on a continuous regular lattice. In this case, Λ(α)≡−q2, where q labels the usual spatial Fourier frequency.

It can be proved that for symmetric graphs, all the non-trivial values of Λ(α) are negative27. Hence, trJα=trJ+(Dφ+Dψ)Λ(α)<0. For the instability to manifest, it is therefore sufficient that detJα=detJ+(J11Dψ+J22Dφ)Λ(α)+DψDφ(Λ(α))2<0, a condition that can be met only if:

When the above quantity is negative, the Turing instability on a regular lattice, or on a complex symmetric network, cannot take place. One can further elaborate on the implications of equation (5), by recalling that trJ=J11+J22<0. Hence, the instability can only set in if J11 and J22 have opposite signs. Without losing generality, we shall hereafter assume J11>0, and consequently J22<0, with |J22|>J11 so as to have trJ<0. In practical terms, the first species, whose concentration reads φ, acts as an activator, while the second, ψ, is the inhibitor. Working in this setting, it is instructive to consider the limiting condition Dψ=0: only the activators (Dφ≠0) can diffuse. The necessary condition (5) reduces to J22Dφ>0, which is never satisfied as J22<0. In principle, a short wavelength instability can develop if the inhibitors are mobile, Dψ≠0, and the activator fixed Dφ=0. In fact, from the dispersion relation (4), it follows that all modes with |Λα|>detJ/(DψJ11) are unstable, both on a continuous or discrete support. In the former, the number of unstable modes is infinite, whereas it is finite in the latter. In both cases, the instability involves smaller and smaller spatial scales, and it is therefore termed a short wavelength instability. In the discrete case, and because the set of unstable modes is finite (and bounded), the instability can drive the emergence of stationary stable patterns.

We end this section with an important remark. As trJα<0, it is clear from equation (4) that it is not possible to satisfy the condition for the instability (λα)Re>0, and have, at the same time, an imaginary component of the dispersion relation, (λα)Im, different from zero. This is instead possible when operating in a setting that allows long-range couplings in the reaction terms28 or when considering at least three mutually interacting species13,20. A system unstable for Λ(α)≠0 and with the corresponding (λα)Im≠0 is said to undergo a wave instability and the emerging patterns have the form of travelling waves28. As we will discuss in the following, the general scenario that we have outlined here changes drastically when the reaction–diffusion system operates on a directed graph rather that on a symmetric network.

Theory of pattern formation on a directed network

We now turn to considering the case of a directed graph. In this case, the adjacency matrix W is no longer symmetric and its entries Wij, if equal to 1, indicate the presence of an edge directed from node i to j. Now,  refers to the outdegree of node i, defined as the number of exiting edges from node i. The associated Laplacian operator can be defined as Δij=Wij−kiδij, as it is customarily done in cooperative control applications29, as, for example, intelligent transportation systems, routing of communications and power grid networks. The spreading of physical or chemical substances, rather than information content, requires imposing mass conservation, which results in a different formulation of the Laplacian operator30, where Wij is formally replaced by Wji in the definition of Δij, as it can be readily obtained from a simple microscopic derivation. Clearly, the two operators coincide, when defined on a symmetric network.

refers to the outdegree of node i, defined as the number of exiting edges from node i. The associated Laplacian operator can be defined as Δij=Wij−kiδij, as it is customarily done in cooperative control applications29, as, for example, intelligent transportation systems, routing of communications and power grid networks. The spreading of physical or chemical substances, rather than information content, requires imposing mass conservation, which results in a different formulation of the Laplacian operator30, where Wij is formally replaced by Wji in the definition of Δij, as it can be readily obtained from a simple microscopic derivation. Clearly, the two operators coincide, when defined on a symmetric network.

For a directed graph, the eigenvalues of both Laplacian operators, will in general be complex, Λ(α)εC. This property requires the development of a generalized theory of the instabilities, extending the analysis outlined in the previous section. As usual, we will assume a stable homogeneous fixed point, which should be a solution of the spatially extended system of equations. This prescription implies dealing with a balanced network (the outgoing connectivity equals the incoming one), when Fickean diffusion of material entities is being addressed Δij=Wji−kiδij, while no additional hypothesis on the structure of the spatial support are to be made when the operator Δij=Wij−kiδij is used. The case of unbalanced networks could be also addressed, provided one linearizes equation (1) around a non-homogeneous state21,31. This more technical extension will be discussed elsewhere, as here the aim is to provide a pedagogical introduction to the novel class of topology-driven instabilities. We indicate with J the Jacobian matrix associated with the homogeneous fixed point. The stability of the fixed point implies trJ<0 and detJ>0. To proceed with the linear stability analysis, we must ensure that the eigenvectors are linearly independent. This is not always the case when the underlying graph is directed. For this reason, the diagonalizability of the Laplacian matrix will be a minimal requirement to satisfy in our analytical treatment of the stability problem. In fact, even without a complete basis, one can use the generalized eigenvectors to make progress. In this case, however, patterns may emerge, even when the real part of the dispersion relation is negative everywhere, due to a transient growth process32.

Introducing an inhomogeneous perturbation (δφi, δψi) and linearizing around it, one eventually obtains a dispersion relation, formally identical to equation (4), where now Λ(α) is a complex quantity. For simplicity, and with obvious meaning of the notation, we write  , where

, where  , as the Laplacian matrix spectrum falls, according to the Gerschgorin circle theorem33, in the left half of the complex plane. A simple algebraic manipulation yields the following preliminary relations:

, as the Laplacian matrix spectrum falls, according to the Gerschgorin circle theorem33, in the left half of the complex plane. A simple algebraic manipulation yields the following preliminary relations:

where (·)Re and (·)Im select, respectively, the real and imaginary parts of the quantity in between brackets. To study the dispersion relation (4), we shall make use of an elementary property of the square root of a complex number z=a+bi, namely that

where sgn(·) is the standard sign function. In light of this consideration, the dispersion relation can be cast in the form:

where:

and:

The dispersion relation can now contain an imaginary contribution, which bears the signature of the imposed network topology. Travelling waves can in principle materialize for a two species reaction–diffusion model on a directed network, at variance with what happens when the system is defined on a symmetric spatial support. For the instability to occur, (λα)Re must be >0, which is equivalent to setting |(trJα)Re|≤γ, as it follows immediately from equation (8). A straightforward, although lengthy, calculation that involves relations (6), allows us to rewrite the condition for the instability in the compact form:

where S1 and S2 are polynomials in  , of fourth and second degree, respectively. The coefficients of the polynomials are model dependent, as specified in equations (16), (17) and (18) in the Methods. Given the model, one can construct a class of graphs, namely those whose spectral properties match condition (11), for which the instability takes place. Here we are particularly interested in models that cannot develop the instability when defined on a symmetric, hence undirected, graph. In this case,

, of fourth and second degree, respectively. The coefficients of the polynomials are model dependent, as specified in equations (16), (17) and (18) in the Methods. Given the model, one can construct a class of graphs, namely those whose spectral properties match condition (11), for which the instability takes place. Here we are particularly interested in models that cannot develop the instability when defined on a symmetric, hence undirected, graph. In this case,  , by definition, and the instability condition (11) cannot be met. On the contrary, when the graph is made directed,

, by definition, and the instability condition (11) cannot be met. On the contrary, when the graph is made directed,  and the examined models can experience a topology-driven instability, as governed by (11).

and the examined models can experience a topology-driven instability, as governed by (11).

Recall that we are linearizing around a stable fixed point; hence trJ=J11+J22<0 and, in addition, detJ>0. Because of the first inequality, the setting with both J11 and J22 positive is, as expected, ruled out a priori. Consider instead the dual scenario, where both J11, J22 are taken to be negative. Hence, S1 and S2 are positive, as it can be immediately appreciated by direct inspection of equations (17) and (18) in the Methods, and the instability condition (11) cannot be achieved. In conclusion, and in agreement with the standard theory of pattern formation on a regular symmetric lattice (network), J11 and J22 must have opposite signs for the instability to develop.

In analogy with the preceding discussion, we assume that the reaction–diffusion scheme is such that J11>0 and J22<0. We imagine here that the necessary condition (5) for the instability to set in is not satisfied and no patterns can develop according to the classical paradigm. Under this assumptions, although S1 is still a positive definite quantity, S2 can take negative values, as C20=J11J22(Dφ−Dψ)2<0. The instability condition (11) can then be satisfied and one can expect topology-driven instabilities to develop on directed graphs, as we shall demonstrate in the forthcoming section.

We also wish to emphasize that patterns on a directed network can also emerge when the inhibitors are prevented from diffusing (Dψ=0, in our notation), at odds with the conventional vision19. Furthermore, travelling waves are always found for a two-species model, the imaginary part of the dispersion relation λα being at all times different from zero, inside the instability domain. However, as we will demonstrate in the next section, when (λα)Im≪(λα)Re, the system evolves towards a stationary inhomogeneous pattern, reminiscent of the Turing instability. In conclusion, a two-species reaction–diffusion system on a directed graph can display a rich variety of instabilities, beyond the conventional scenario, which applies to symmetric (undirected) spatial supports.

Numerical results

To confirm the theoretical analysis carried out in the previous section, we here focus on a specific system, the so-called Brusselator model, a paradigmatic example of autocatalytic reactions. In the general dynamical equation (1), we set  and

and  . Details of this model are presented in the Methods section. It is worth stressing that the Brusselator model has been selected for demonstrative purposes, and due to its pedagogical value. The techniques here developed, and the conclusions that we shall reach, are nevertheless general and apply to a wide range of models. As an example, in Supplementary Methods we will repeat the same analysis for a version of the Fitzhugh–Nagumo scheme, that serves as a toy model for inspecting the coupled dynamics of neurons. Supplementary Movie 2 shows the waves stemming from the instability in this system.

. Details of this model are presented in the Methods section. It is worth stressing that the Brusselator model has been selected for demonstrative purposes, and due to its pedagogical value. The techniques here developed, and the conclusions that we shall reach, are nevertheless general and apply to a wide range of models. As an example, in Supplementary Methods we will repeat the same analysis for a version of the Fitzhugh–Nagumo scheme, that serves as a toy model for inspecting the coupled dynamics of neurons. Supplementary Movie 2 shows the waves stemming from the instability in this system.

Here we consider the first formulation of the Laplacian operator, Δij=Wij−kiδij, which, as previously mentioned, is employed in cooperative control applications29. To proceed, we should also specify the characteristics of the networks that define the spatial backbone for the explored systems. Two different strategies for generating the graphs will be considered. On the one side, we will follow the Watts–Strogatz (WS) approach34, modified to make the network directed. We will also implement an alternative generation strategy, the so-called Newman–Watts (NW) algorithm35. Both approaches are described in the Methods section. When Δij=Wji−kiδij is assumed instead, the directed networks are created with the additional prescription to balance the number of incoming and outgoing connections per node. Results for this choice of the Laplacian are presented in Supplementary Figs 2 and 8.

In the following, we will report the emergence of topology-driven instabilities, defined on directed networks assembled via the two strategies mentioned here.

Travelling waves for systems of two diffusing species

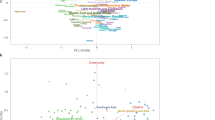

We commence by considering the Brusselator model in the general setting with Dφ≠0 and Dψ≠0. That is, both the activators and inhibitors are allowed to diffuse between connected nodes of the network. Furthermore, we set the parameters so that the system is stable versus external perturbations of the homogeneous fixed point and no patterns can develop if the spatial support is assumed symmetric (or continuous). The generalized condition (11) for the instability on a directed network can be graphically illustrated in the reference plan  . Given the parameters of the model, one can in fact determine the coefficients C1q (q=0, ..., 4) and C2q (q=0, 1, 2) via equations (17) and (18) in the Methods. Next, the inequality (11) allows one to delimit a model-dependent region of instability, which is depicted with a shaded area in Fig. 1a. Each eigenvalue of the discrete Laplacian (defined on the directed network) appears as a point in the plane

. Given the parameters of the model, one can in fact determine the coefficients C1q (q=0, ..., 4) and C2q (q=0, 1, 2) via equations (17) and (18) in the Methods. Next, the inequality (11) allows one to delimit a model-dependent region of instability, which is depicted with a shaded area in Fig. 1a. Each eigenvalue of the discrete Laplacian (defined on the directed network) appears as a point in the plane  . If a subset of the Ω points that define the spectrum of the Laplacian fall inside the region outlined above, the instability can take place. For an undirected graph,

. If a subset of the Ω points that define the spectrum of the Laplacian fall inside the region outlined above, the instability can take place. For an undirected graph,  , and the points are located on the real (horizontal) axis, thus outside the instability domain. In Fig. 1a, the spectral plot of three Laplacians, generated from the NW algorithm, are displayed for three choices of p. As p increases the points move to the left, away from the region of instability. The regular ring that captures the eigenvalue distribution for low p (blue triangles) becomes progressively distorted: for p=0.95, the points (green diamonds) partially fill a circular patch in (

, and the points are located on the real (horizontal) axis, thus outside the instability domain. In Fig. 1a, the spectral plot of three Laplacians, generated from the NW algorithm, are displayed for three choices of p. As p increases the points move to the left, away from the region of instability. The regular ring that captures the eigenvalue distribution for low p (blue triangles) becomes progressively distorted: for p=0.95, the points (green diamonds) partially fill a circular patch in ( ). In Fig. 1b, the real part (λα)Re of the dispersion relation is plotted as a function of

). In Fig. 1b, the real part (λα)Re of the dispersion relation is plotted as a function of  . The black solid line refers to the continuous theory: no instability can develop in the limit of continuum space, as (λα)Re is always negative. However, when the Brusselator model evolves on a discrete support, the continuous line is replaced by a collection of Ω points. When the instability condition (11) is fulfilled, the points are lifted above the solid curve and cross the horizontal axis. The figure shows that (λα)Re is positive over a finite domain in

. The black solid line refers to the continuous theory: no instability can develop in the limit of continuum space, as (λα)Re is always negative. However, when the Brusselator model evolves on a discrete support, the continuous line is replaced by a collection of Ω points. When the instability condition (11) is fulfilled, the points are lifted above the solid curve and cross the horizontal axis. The figure shows that (λα)Re is positive over a finite domain in  and the system becomes unstable due to the topology of the underlying directed network. The travelling waves that stem from this instability are displayed in Fig. 2, and also in Supplementary Movie 1. As we shall prove in the following, inhomogeneous stationary patterns are another possible outcome of the topology-driven instability.

and the system becomes unstable due to the topology of the underlying directed network. The travelling waves that stem from this instability are displayed in Fig. 2, and also in Supplementary Movie 1. As we shall prove in the following, inhomogeneous stationary patterns are another possible outcome of the topology-driven instability.

(a) Spectral plot of three Laplacians generated from the NW algorithm for p=0.27, p=0.5 and p=0.95 (blue triangles, red circles and green diamonds, respectively) and network size Ω=100. The shaded area indicates the instability region for the case of the Brusselator model, where the parameters are b=9, c=30, Dφ=1 and Dψ=7. (b) The real part of the dispersion relation for the same three choices of NW networks as in a. The black line originates from the continuous theory.

Time series for the case of the Brusselator model on an NW network, generated with p=0.27. The nodes are ordered as per the original lattice. Details of the network’s spectra and the system’s instability are displayed by the blue, triangular symbols in Fig. 1. The reaction parameters are b=9, c=30, Dφ=1 and Dψ=7.

A similar analysis can be performed when the directed network is generated using the WS method. In Fig. 3a, the region of instability, outlined by the shaded area, is identical to the one depicted in Fig. 1, as the parameters of the reaction–diffusion scheme are unchanged. Here the topology-driven instability occurs for relatively large values of the parameter p, when the random nature of the network takes over its small world character. The travelling waves for this system are displayed in Fig. 4.

(a) Spectral plot of three Laplacians generated from the WS method for p=0.1, p=0.2 and p=0.8 (blue triangles, red circles and green diamonds, respectively). In all cases, the network size is Ω=100. The coloured area indicates the instability region for the Brusselator model. (b) The real part of the dispersion relation for three choices of WS networks for p=0.1, p=0.2 and p=0.8 (blue triangles, red circles and green diamonds, respectively), and network size Ω=100. The reaction parameters are b=9, c=30, Dφ=1 and Dψ=7.

Time series for the case of the Brusselator model on a WS network, generated with p=0.1. The nodes are ordered as per the original lattice. Details of the network’s spectra and the system’s instability are displayed by the blue, triangular symbols in Fig. 3. The reaction the parameters are b=9, c=30, Dφ=1 and Dψ=7.

The case of immobile inhibitors

As mentioned earlier, patterns can also emerge on a directed network when the inhibitors are prevented from diffusing (Dψ=0). This is a marginal condition for which classical patterns (both in the continuum limit or on an undirected network support) are not found. In Fig. 5a, the condition of instability is represented. The symbols (blue triangles) refer to an NW graph with p=0.27 and fall inside the shaded domain, signalling the existence of a topology-driven instability. The same conclusion can be reached on inspection of Fig. 5b, where the real part of the dispersion relation is plotted and shown to be positive over finite window in  . The travelling waves found in this case are shown in Fig. 6.

. The travelling waves found in this case are shown in Fig. 6.

(a) Spectral plot for an NW network with p=0.27 and Ω=100. The instability region is plotted for the choice of the Brusselator model, where the diffusion Dψ has been set to zero. (b) The real part of the dispersion relation for an NW network with Ω=100, generated with P=0.27. The black line is found from the continuous theory. The full parameter set is: b=9, c=8.2, Dφ=1 and Dψ=0.

Time series obtained from the Brusselator model on an NW network, in the case where Dψ=0. The network was constructed using p=0.27. Details of the network’s spectra and the system’s instability are displayed by the blue, triangular symbols in Fig. 5. The full parameter set is: b=9, c=8.2, Dφ=1 and Dψ=0.

Stationary inhomogeneous patterns

The instability mechanism that we have discussed here results in travelling waves, which spread over the direct network. This is due to the fact that the imaginary part of the dispersion relation λα is always different from zero, inside the instability domain. Hence, Turing-like instabilities, which require imposing (λα)Im=0, cannot formally develop. On the other hand, as we argued earlier, stationary inhomogeneous patterns reminiscent of the Turing instability could be observed, provided (λα)Im≪(λα)Re. This is the case considered here, as shown in Fig. 7, for a directed network generated via the WS recipe. The parameters of the Brusselator model are instead set as in Fig. 1. This is to stress again that different types of patterns can emerge because of the distinct characteristics of the networks: the patterns are not just selected by the imposed dynamical rules. The most unstable mode is located at around  (left panel of Fig. 7), and its corresponding value of (λα)Im is relatively small (right panel of Fig. 7). The patterns found in this situation are shown in the two panels of Fig. 8. By comparing Fig. 4 (WS with p=0.1) with Fig. 8 (WS with p=0.2), it is immediately clear that a transition takes place, from travelling waves to asymptotically stationary stable patterns, by tuning the rewiring probability p in the WS graph generation scheme.

(left panel of Fig. 7), and its corresponding value of (λα)Im is relatively small (right panel of Fig. 7). The patterns found in this situation are shown in the two panels of Fig. 8. By comparing Fig. 4 (WS with p=0.1) with Fig. 8 (WS with p=0.2), it is immediately clear that a transition takes place, from travelling waves to asymptotically stationary stable patterns, by tuning the rewiring probability p in the WS graph generation scheme.

(a) The real part of the dispersion relation for a WS network with a Brusselator dynamic. The network is of size Ω=100, generated with p=0.2. (b) The imaginary part of the dispersion relation for a WS network with a Brusselator dynamic. The network is of size Ω=100, generated with p=0.2. The reaction parameters are b=9, c=30, Dφ=1 and Dψ=7.

(a) Time series showing quasi-Turing patterns on a WS network with a Brusselator dynamic. The network was generated using p=0.2. The system evolves from a homogeneous fixed point towards a static pattern. (b) The long-time behaviour of the network, showing the concentration of each node. The dispersion relation for this system is presented in Fig. 7. The reaction parameters are b=9, c=30, Dφ=1 and Dψ=7.

Discussion

In a recent paper, Nakao and Mikhailov19 revisited the theory of Turing pattern formation on random symmetric networks, highlighting the peculiarities that stem from the embedding graph structure and extending the pioneering work of Othmer and Scriven14,15. Travelling waves can also set in following an analogous mechanism20.

Starting from this context, and to reach a number of potential applications, we have here considered the extension of the analysis in ref. 19 to the case of directed, hence non-symmetric, networks. It is often the case that links joining two distant nodes are defined with an associated direction: the reactants can move from one node to another, but the reverse action is formally impeded. In this study, we have shown that a novel class of instability, here termed ‘topology driven’, can develop for reaction–diffusion systems on directed graphs, also when the examined system cannot experience a Turing-like or wave instability when defined on a regular lattice or, equivalently, on a continuous spatial support. This is at variance with the case of symmetric networks, which cannot possess the intrinsic ability of destabilizing an otherwise stable homogenous fixed point. We have shown here that different patterns can be generated depending on the characteristics of the spatial support on which the reaction–diffusion system is defined. In particular, transitions from travelling waves to asymptotically stationary stable patterns, reminiscent of the Turing instability, are obtained when tuning the rewiring probability p in a WS network. The condition for the instability results in a rather compact mathematical criterion, which accounts for the spectral properties of the underlying network and whose predictive adequacy has been validated with reference to selected case studies. We note that a numerical characterization of the instability domain could also be carried out using the Master Stability Function approach36.

The existence of a generalized class of instabilities, seeded by the topological characteristics of the embedding support, suggests a shift in the conventional approach to modelling of dynamical systems. Mutual rules of interactions, which define the reactions among constituents, are certainly important, although not decisive in determining the asymptotic fate of the system. The topology of the space, when assumed to be a directed random network, also matters and plays an equally crucial role in the onset of the dynamical instability. This is a general conclusion that we have cast in rigorous terms, which can potentially inspire novel avenues of research in all those domains, from neuroscience to social-related applications, where networks prove essential.

Methods

Details of the linear stability analysis

To look for instabilities in equation (1), one can introduce a small perturbation (δφi, δφi) to the fixed point and linearize around it. In formulae one finds

where

Expanding the perturbation on the basis of the eigenvectors of the network Laplacian, (see equation (3)), one obtains the following eigenvalue problem

This is equivalent to

where Jα≡J+DΛ(α) and I stands for the identity matrix. The eigenvalue with the largest real part, λα≡λα(Λ(α)) defines the dispersion relation presented in equation (4).

Specification of the instability region

Here we provide details of the functions S1 and S2, introduced in equation (11) of the paper, using the quantities defined in equation (6). We eventually obtain

where

and

Details of the Brusselator model

The Brusselator model involves molecules of two chemical species, whose concentrations are here labelled φ and ψ to make contact with the notation employed in the preceding sections. The species populate the nodes of a network, and therein interact according to the prescribed dynamics, while being allowed to diffuse between adjacent nodes. More specifically, the system evolves according to the general dynamical equation (1) with  and

and  , b and c acting as external, positive definite, parameters. The Brusselator model admits a unique homogeneous fixed point φ*=1, ψ*=b/c, which is stable for b<1+c. We additionally require b>1, such that J11=−1+b>0, while J22=−c<0. The system can develop Turing-like patterns for specific choices of the control parameters (b, c). In this investigation, we assign the parameter values so as to fall outside the domain of instability. The fixed point (φ*, ψ*) is therefore stable versus non-homogeneous perturbations, when placed on top of a symmetric graph.

, b and c acting as external, positive definite, parameters. The Brusselator model admits a unique homogeneous fixed point φ*=1, ψ*=b/c, which is stable for b<1+c. We additionally require b>1, such that J11=−1+b>0, while J22=−c<0. The system can develop Turing-like patterns for specific choices of the control parameters (b, c). In this investigation, we assign the parameter values so as to fall outside the domain of instability. The fixed point (φ*, ψ*) is therefore stable versus non-homogeneous perturbations, when placed on top of a symmetric graph.

Network generation

The WS method is a random graph generation model that produces graphs with the small world property. In short, given the desired number of nodes Ω and the mean degree K, we first construct a K-regular ring lattice, by connecting each node to its K neighbours, on one side only. Next, for every node i, we take all edges and rewire them with a given probability pε[0, 1]. Rewiring is carried out by replacing the target node, with one of the other nodes, say j, selected with a uniform probability, and avoiding self-loops (i≠j) and link duplication. Therefore, the mean number of rewired links is ΩKp. The rewiring is directed: we do not impose a symmetric edge that goes from the selected target node j, back to the starting site i. Small world networks are found for intermediate values of p. Link duplication is avoided here, so that the effects of the directed network (which we wish to demonstrate) are not confused with effects of a weighted network.

We also implement a variation of this strategy, the so-called NW algorithm. In this case, all of the original links in the directed lattice are preserved and extra links are added. As before, we start from a substrate K-regular ring made of Ω nodes. To make connection with the WS route, the algorithm is designed to add, on average, ΩKp long-range directed links, in addition to the links due to the regular lattice35,37. Again pε[0, 1] is a probability to be chosen by the user. The NW algorithm can be modified so as to result in a balanced network (identical number of incoming and outgoing links, per node). To this end, the inclusion of a long-range link starting from node i is followed by the insertion of a fixed number (3 is our arbitrary choice) of additional links to form a loop that closes on i.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Asllani, M. et al. The theory of pattern formation on directed networks. Nat. Commun. 5:4517 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5517 (2014).

References

Turing, A. M. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Phil Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 237, 37 (1952).

Mimura, M. & Murray, J. D. On a diffusive prey-predator model which exhibits patchiness. J. Theor. Biol. 75, 249 (1978).

Maron, J. L. & Harrison, S. Spatial pattern formation in an insect host-parasitoid system. Science 278, 1619 (1997).

Baurmann, M., Gross, T. & Feudel, U. Instabilities in spatially extended predator-prey systems: spatio-temporal patterns in the neighborhood of Turing-Hopf bifurcations. J. Theor. Biol. 245, 220 (2007).

Rietkerk, M. & van de Koppel, J. Regular pattern formation in real ecosystems. Trends Ecol. Evol. 23, 169 (2008).

Meinhardt, H. & Gierer, A. Pattern formation by local self-activation and lateral inhibition. BioEssays 22, 753 (2000).

Harris, M. P., Williamson, S., Fallon, J. F., Meinhardt, H. & Prum, R. O. Molecular evidence for an activator-inhibitor mechanism in development of embryonic feather branching. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 11734 (2005).

Maini, P. K., Baker, R. E. & Chuong, C.-M. The Turing model comes of molecular age. Science 314, 1397 (2006).

Newman, S. A. & Bhat, R. Activator-inhibitor dynamics of vertebrate limb pattern formation. Birth Defects Res. (Part C) 81, 305 (2007).

Miura, T. & Shiota, K. TGFβ2 acts as an “activator” molecule in reaction-diffusion model and is involved in cell sorting phenomenon in mouse limb micromass culture. Dev. Dyn. 217, 241 (2000).

Murray, J. D. Mathematical Biology Second Edition Springer (1991).

Wyller, J., Blomquist, P. & Einevoll, G.T. Turing instability and pattern formation in a two-population neuronal network model. Phys. D 225, 75–93 (2007).

Zhabotinsky, A. M., Dolnik, M. & Epstein, I. R. Pattern formation arising from wave instability in a simple reaction-diffusion system. J. Chem. Phys. 103, 10306 (1995).

Othmer, H. G. & Scriven, L. E. Instability and dynamic pattern in cellular networks. J. Theor. Biol. 32, 507–537 (1971).

Othmer, H. G. & Scriven, L. E. Non-linear aspects of dynamic pattern in cellular networks. J. Theor. Biol. 43, 83–112 (1974).

Jansen, V. A. A. & Lloyd, A. L. Local stability analysis of spatially homogeneous solutions of multi-patch systems. J. Math. Biol. 41, 232–252 (2000).

Plahte, E. Pattern formation in discrete cell lattices. J. Math. Biol. 43, 411–445 (2001).

Moore, P. K. & Horsthemke, W. Localized patterns in homogeneous networks of diffusively coupled reactors. Phys. D 206, 121–144 (2005).

Nakao, H. & Mikhailov, A. S. Turing patterns in network-organized activator-inhibitor systems. Nat. Phys. 6, 544 (2010).

Asllani, M., Biancalani, T., Fanelli, D. & McKane, A. The linear noise approximation for reaction-diffusion systems on networks. Eur. Phys. J. B 86, 476 (2013).

Angstmann, C. N., Donnelly, I. C. & Henry, B. I. Pattern formation on networks with reactions: A continuous-time random-walk approach. Phys. Rev. E 87, 032804 (2013).

John, W., Dusi, M. & Claffy, K. in:Tech. rep., ACM 1st International Workshop on TRaffic Analysis and Classification (TRAC) ACM (2010).

Kandel, E. R., Schwartz, J. H. & Jessell, T. M. Principles of Neural Science Fourth Edition McGraw-Hill (2000).

Lichtman, J. W. & Denk, W. The big and the small: challenges of imaging the brain’s circuits. Science 334, 618 (2011).

Sporns, O., Tononi, G. & Kötter, R. The human connectome: a structural description of the human brain. PloS Comp. Biol. 1, e42 (2005).

Human Connectome Project http://www.humanconnectomeproject.org/.

Newman, M. E. J. Networks: An Introduction Oxford University Press (2010).

Biancalani, T., Galla, T. & McKane, A. J. Stochastic waves in a Brusselator model with nonlocal interaction. Phys. Rev. E 84, 026201 (2011).

Olfati-Saber, R. & Murray, R. M. Consensus problems in networks of agents with switching topology and time-delays. IEEE Trans. Auto. Control 49, 1520–1533 (2004).

Banerjee, A. & Jost, J. On the spectrum of the normalized graph Laplacian. Linear Algebra Appl. 428, 3015–3022 (2008).

Angstmann, C. N., Donnelly, I. C., Henry, B. I. & Langlands, T. A. M. Continuous-time random walks on networks with vertex-and time-dependent forcing. Phys. Rev. E 88, 022811 (2013).

Ridolfi, L., Camporeale, C., D'Odorico, P. & Laio, F. Transient growth induces unexpected deterministic spatial patterns in the Turing process. Europhys. Lett. 95, 18003 (2011).

Bell, H. E Gershgorin’s theorem and the zeros of polynomials. Am. Math. Monthly 72, 292–295 (1965).

Watts, D. J. & Strogatz, S. H. Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature 393, 440–442 (1998).

Newman, M. E. J. & Watts, D. J. Scaling and percolation in the small-world network model. Phys. Rev. E 60, 7332–7342 (1999).

Pecora, L. M. & Carroll, T. L. Master stability functions for synchronized coupled systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 2109–2112 (1998).

Newman, M. E. J. The structure and function of complex networks. SIAM Rev. 45, 167–256 (2003).

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement no. 604102 (Human Brain Project).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A., J.D.C. and D.F. designed the study and carried out the analysis. L.S. and F.S.P. contributed to the interpretation of the results and M.A. performed the numerical simulations. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Figures, Methods and References

Supplementary Figures 1-8, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 2212 kb)

Supplementary Movie 1

This movie shows the evolution of the pattern for the Brusselator model on a Newman-Watts network with 100 nodes with p = 0.27 starting from the homogenous fixed point ⬜* = 1. The model parameters are: b = 9, c = 30, D□ = 1 and Dψ = 7. The vertical axis represents the magnitude of species ⬜ and the horizontal axis the corresponding node. (AVI 5468 kb)

Supplementary Movie 2

This movie shows the travelling wave on a Newman-Watts network with 100 nodes for the FitzHugh-Nagumo model. The model parameters are: a = 0.5, b = 0.04, c = 26, Du = 0.2 and Dv = 15. The vertical axis represents the magnitude of species ⬜ and the horizontal axis the corresponding node. (AVI 5251 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Asllani, M., Challenger, J., Pavone, F. et al. The theory of pattern formation on directed networks. Nat Commun 5, 4517 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5517

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5517

This article is cited by

-

A time independent least squares algorithm for parameter identification of Turing patterns in reaction–diffusion systems

Journal of Mathematical Biology (2024)

-

Synchronization induced by directed higher-order interactions

Communications Physics (2022)

-

Turing patterns of Gierer–Meinhardt model on complex networks

Nonlinear Dynamics (2021)

-

Spatiotemporal patterns in a general networked activator–substrate model

Nonlinear Dynamics (2021)

-

Turing Patterning in Stratified Domains

Bulletin of Mathematical Biology (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.