Abstract

Presence of human papillomavirus (HPV) in variable proportions in tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma tissues has been demonstrated by several worldwide studies. Some reports emphasized the significance of HPV in predicting a better prognosis, as well as ethnic differences between Chinese and Caucasians. In order to understand the biological role of HPV and find out clinically accessible methods to determine its prognostic significance in primary tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma, we collected 92 patients with primary tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma diagnosed or treated in National Taiwan University Hospital, for whom archival tumor tissue were available. Immunohistochemical stains of p16INK4A, high-risk HPV in situ hybridization, and nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based genechips were performed to detect HPV infection and determine its genotype. Clinical data were compared with HPV infection detected by the different methods mentioned above. Real-time PCR was also performed on the HPV16-positive [HPV16(+)] lesions to understand viral integration status. The positive rates of nested PCR-based genechips, overexpression of p16INK4A, and high-risk HPV in situ hybridization were 75% (69/92), 53% (49/92), and 44% (40/92), respectively. Both overexpression of P16INK4A and high-risk HPV in situ hybridization positivity were associated with favorable prognoses (P=0.004 and 0.001, respectively) and also independent prognostic factors in multivariate analyses (P=0.01 and 0.01, respectively). The positivity of nested PCR-based genechips was not statistically significant. From our data, primary tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma with positive immunohistochemical stains of p16INK4A and/or high-risk HPV in situ hybridization is associated with a better outcome, and both methods may serve as clinically accessible markers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In the United States, the annual incidence of head and neck cancer is approximately 30 900 cases;1 the worldwide annual incidence of head and neck cancer also makes it the fifth most common cancer in the world.2 In Taiwan, it ranks as the fifth most prevalent cancer in both sexes, and accounts for the fourth most common cancer in males.3 These tumors have diverse clinical features and distinctive natural histories, and their treatment involves surgery, radiotherapy or chemotherapy alone, or in different sequential combinations. Prognosis has not really improved during the past two decades, although there have been improvements in our understanding of the spreading patterns of invasive tumors, leading to the increased use of combined modality treatment. Clinical staging currently guides treatment but still remains an uncertain predictor of outcome.

Although oral habits like betel nut chewing, cigarette smoking, and alcohol drinking are thought to be major risk factors responsible for the development of oral squamous cell carcinomas in Taiwan, there is a small proportion of patients who do not use betel nut, tobacco or alcohol, yet still develop oral cancer.4, 5 Several other reports have indicated that patients without oral habits or who are young adults may also develop oral squamous cell carcinoma.6, 7, 8 Such evidence implies that carcinogenesis by environmental chemical carcinogens is not the only cause of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Presence of human papillomavirus (HPV), especially those genotypes with known high oncogenic potential in the uterine cervix (such as HPV16 and 18), in variable proportions in the oral squamous cell carcinoma tissues has been demonstrated by several worldwide studies.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 Recent studies suggest that HPV, especially type 16, may be responsible for a small subgroup of oral squamous cell carcinoma and up to 50% of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas, especially the tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma,26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 despite an ethnic difference between Chinese and Caucasians, as noted in one report.34 Some reports emphasized the influences of HPV in predicting a better disease prognosis in oropharyngeal and tonsillar cancers.28, 29 Furthermore, a strong association between the presence of HPV and expression of key cell cycle proteins has been recently reported in a series of tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma.26, 27 These data seem to strongly suggest that HPV-positive tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma represents a distinct molecular, clinical and pathologic entity. In the present study, we will focus on this distinct subgroup of head and neck cancers.

According to earlier investigations,35, 36, 37, 38 high-risk HPVs and two HPV-related oncoproteins E6 and E7 can immortalize and transform oral keratinocytes in vitro. These cumulated evidences suggest that HPVs may play a crucial role in the carcinogenesis of head and neck cancer. When the host epithelial cell is infected with the HPV, the HPV genome integrates into the host cell's DNA. It will typically disrupt the HPV E1/E2 open reading frame, resulting in the loss of function of E2, a physiological regulatory protein for the HPV E6 and E7 oncogenes.39, 40 The E2F–pRb complex dissociates in the presence of the HPV oncoprotein E7; this, in turn, activates E2F, thereby initiating the transcription of genes required for DNA replication and inappropriately forcing the cell past the G1/S restriction point into the S phase.41, 42, 43 Due to positive feedback, the functional inactivation of pRb by HPV E7 results in the reciprocal overexpression of p16INK4A.40, 44, 45, 46, 47 Therefore, p16INK4A has been considered a complimentary surrogate biomarker for HPV-related uterine cervical and vulvar neoplasia.48, 49, 50 The same phenomenon was also noted in HPV-related tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma.26 In accordance with the mechanism described above, previous reports demonstrated a unique region of the E2 open reading frame that is most often deleted during HPV16 integration. Using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), if E2 open reading frame is targeted by one set of PCR primers and a probe, and another set targets the E6 open reading frame, both targets should theoretically be equivalent in episomal form, while in integrated form, the copy numbers of E2 would be less than those of E6.51

We used three methods, including nested PCR-based genechips, immunohistochemical staining of p16INK4A, and high-risk HPV in situ hybridization, to detect HPVs and determine their genotypes in 92 primary tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma cases. We then performed real-time PCR to detect DNA products of E2 and E6 open reading frame, in order to calculate the E2/E6 ratio in HPV16-positive cases. Comparing the clinical and pathologic data of the patients (including staging, survival, oral habits, and histological type, etc.), we hoped to further understand the biological effects of HPV in these tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma cases.

Materials and methods

Patients

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks of 92 Taiwanese patients, 79 male (median age 51, 29–79) and 13 female (median age 49, 42–79), were obtained from patients diagnosed with primary tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma based on histological examination of hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissue sections according to the World Health Organization Classification of Tumors.52 Keratinizing tumor cells could be found in 47 of 92 (51%) cases. All patients received biopsy or surgical operation between 1997 March and 2005 March at the National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan. The clinical data were abstracted from the patient's medical charts and the survival data were obtained from the Bureau of Health Promotion, Taiwan.

Immunohistochemical and In Situ Hybridization

For immunohistochemical staining, a 5-μm thick section of the tumor tissue was deparaffinized, rehydrated, and then underwent antigen retrieval (DAKO target retrieval solution, high pH, S3307, autoclaved, 10 min). After cooling for 20 min at room temperature, decant retrieval solution was washed 2–3 times in room temperature using PBS solution. The primary antibody p16INK4A (neomarker; JC-8, 1:50 dilution) was added and the specimen was incubated at 4°C overnight. Staining was performed using the Ventana autostainer (DAB detection kit; iVIEW, Ventana Medical Systems, SA, USA). The cases with more than 50% of tumor cells showing strong nuclear staining with/without cytoplasmic staining were considered positive53 (Figure 1a). The in situ hybridization of high-risk HPV was performed using Ventana autostainer (INFORM HPV II Family 16 Probe; in situ hybridization iVIEW™ Blue Plus Detection kit; Ventana Medical Systems). According to the manual provided by the manufacturer, each dispenser of the probe we used contains a cocktail of 10 ml of approximately 2 μg/ml of DNP-labeled genomic probes in a formamide-based diluent. This probe cocktail has an affinity to HPV genotypes 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, and 66. Using this method of in situ hybridization, cases with more than 10% of tumor cells containing the integrated form (nuclear dots) of HPV were considered positive (Figure 1b).

DNA Extraction, Nested PCR and Genechips

Four 8-μm tissue sections were cut and deparaffinized, and DNA was extracted using a commercial kit (QIAamp DNA Mini Kit). In order to control the quality and quantity of the isolated DNA, a 300-bp sequence of the β-actin gene was amplified by PCR as internal control to monitor the genomic DNA extraction procedure. Each PCR amplification reaction was carried out in a total volume of 50 μl containing a PCR master mixture (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 50 mM KCl, 800 μM each of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, 600 M dUTP, 10 pmol of each primer set, 1.25 IU/l AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase; Applied Biosystems, San Francisco, California, USA). Each PCR was carried out in the Geneamp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems), with the first denaturation step at 94°C for 3 min and final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. General consensus primers MY09/GP6+ were used for the first PCR round to amplify the corresponding part of the HPV L1 gene in accordance with methods reported by others,54 with some modifications.55, 56, 57 A nested PCR was then carried out with the primers GP5+/GP6+ according to previously published protocols.58 A 15-μl volume of the resultant amplified product was then hybridized with an HPV genechip (Easychip HPV Genotyping Array; King Car, Taipei, Taiwan), which offers a revert-blot hybridization to detect 39 subtypes of HPV DNA in a single reaction, as reported by Huang and co-workers.5, 59

Real-Time PCR

Real-time PCR was performed in all HPV16-positive [HPV16(+)] cases with the ABI Prism 7900 Sequence Detection System and the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Primer and probes used were designed in a previous study51 and synthesized by Purigo and Prisma. The probes were synthesized with the fluorescent reporter dye FAM (6-carboxy-fluorescein) attached to the 5′ end and a non-fluorescent quencher with minor groove binder (Table 1). The amplification program included a preincubation step at 95°C for 10 min to activate the DNA polymerase, and a two-step cycle of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s, and annealing and extension at 60°C for 60 s for a total of 40 cycles. The sizes of the E2 and E6 amplimers were 76 and 81 bp, respectively. The final primer and probe concentrations, in a total volume of 25 μl, were 0.3 and 0.1 M, respectively. A 40-ng weight of genomic DNA from the specimens was added to each reaction mixture. Standard curves were obtained by amplification of a dilution series of a plasmid (King Car, Taipei, Taiwan) solution, which carried the complete HPV16 genome from 107 to 102 copies. The sensitivity of this method was 102 viral copies. Any data outside the standard curves (less than 102 copies) were viewed as representing an absence of viral load. No-template reactions were included as negative control. All experiments were performed in triplicate and the mean of them was calculated. In order to demonstrate the status of infection (episomal, mixed, and integrated), E2/E6 ratio was calculated. Integration was defined as absence of the E2 signal or a E2/E6 ratio less than 0.003.60 A ratio between 0.004 and 0.999 indicates mixed episomal and integrated form, and a ratio not smaller than 1 means the episomal form is predominant.60

Statistical Analysis

Data on clinical and pathological characteristics were compared by the Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables and the χ2-test for categorical variables. For analyses of survival rate, death from any cause was considered an event and data on patients who were alive at the last follow-up contact were censored. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate the probabilities of survival. The multivariate analysis was used for finding out independent variables. The proportional hazards model was used with stepwise backward selection to evaluate independent prognostic factors for survival. These analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows version 11.0 software.

Results

Patient Characteristics and Treatment

The characteristics, treatment, and overall survival of 92 patients are summarized in Table 2. Data on specific treatment modality were lacking in 16 cases. The treatment modalities included surgery alone (n=6), surgery followed by radiotherapy (n=13), surgery followed by concurrent chemoradiation (n=25), radiotherapy alone (n=7), concurrent chemoradiation (n=20), chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy (n=4), and chemotherapy followed by surgery (n=1). We divided the treatment modalities into two groups (definitive surgery and definitive radiotherapy). The overall survival rates between these groups did not differ significantly (data not shown, P=0.94).

Data Associated with HPV Infection Status

Sixty-nine (75%) cases were positive for HPV nested PCR, and HPV DNA types 16, 18, 33, 35, 58, 66, and 69 can be detected in 58, 2, 2, 1, 3, 1, and 2 cases, respectively. The cases with HPV genotypes 35, 58, and 69 were positive for both p16INK4A immunostainings and high-risk HPV in situ hybridization, but all the cases with HPV genotypes 18, 33, and 66 were doubly negative. Among the 58 cases with HPV genotype 16, 34 cases were positive for both p16INK4A immunostaining and high-risk HPV in situ hybridization, five cases were only positive for p16INK4A immunostaining, and 19 cases were doubly negative. Combined with the data of real-time PCR in HPV16(+) cases, more than 102 viral copies were detected in 33 of 34 doubly positive cases (one integrated and 32 mixed), five of five cases positive only for p16INK4A (one integrated, one episomal, and three mixed) and two of 19 doubly negative cases (two mixed). Forty of the HPV16(+) cases contained more than 102 viral copies, according to the real-time PCR method (223–688 689; median 19 909); while the remaining 18 HPV16(+) cases demonstrated less than 102 viral copies, also via the real-time PCR method (0–63; median 4). Among the 23 HPV nested PCR(−) cases, only four of them were positive for p16INK4A immunostaining, but all cases had negative results for high-risk HPV in situ hybridization.

Comparing Clinical Data with Differentiated Methods

HPV-related tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma apparently tends to develop in patients who do not use alcohol, betel nut, or cigarettes, regardless of the method chosen to represent HPV infection (Table 2). A non-keratinizing histological type and a more favorable 5-year survival rate seem to characterize HPV-related tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma with positive p16INK4A immunostaining or high-risk HPV in situ hybridization (Table 2). Statistically, female patients seemed more likely to develop HPV-related tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma when using nested PCR for detection (Table 2).

Survival Analyses

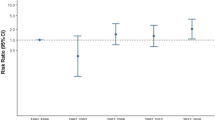

Univariate analysis demonstrated that consumption of alcohol, betel nuts, and cigarettes was significantly associated with shorter survival and that patients with overexpression of p16INK4A or in situ hybridization HPV-positive disease were significantly associated with longer survival (Table 3; Figure 2a–c). HPV-PCR, p16INK4A and in situ hybridization were separately analyzed with all the clinical and pathological variables in multivariate analyses, which demonstrated that both p16INK4A and in situ hybridization were independent prognostic factors, but HPV-PCR was not. In HPV16(+) cases, positive p16INK4A and in situ hybridization were also significantly associated with longer survival (Figure 3a and b). Using real-time PCR, HPV16(+) patients with integrated and mixed forms of HPV DNA also shared significantly longer survival times than those with episomal forms of HPV DNA or lower viral DNA copies (<102) (Figure 3c).

(a) Relationship between overall survival and HPV-PCR positivity in 92 patients with tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma (hazard ratio: 0.61; 95% CI: 0.19–1.69). (b) Relationship between overall survival and p16INK4A immunostaining positivity in 92 patients with tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma (hazard ratio: 0.27; 95% CI: 0.10–0.64). (c) Relationship between overall survival and high-risk HPV in situ hybridization positivity in 92 patients with tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma (hazard ratio: 0.17; 95% CI: 0.10–0.57).

(a) Relationship between overall survival and p16 positivity in 58 patients with HPV16(+) tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma. (b) Relationship between overall survival and high-risk HPV in situ hybridization positivity in 58 patients with HPV16(+) tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma. (c) Relationship between overall survival and HPV integration in 58 patients with HPV16(+) tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma.

Discussion

HPV infection, like alcohol and tobacco, is now recognized to play a role in the pathogenesis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, especially in the tonsillar area, which appears uniquely susceptible to transformation by the virus.5, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 31, 32, 33 HPVs are known not to work via a hit-and-run mechanism; therefore, demonstration of HPV genomic DNA in the tumor is essential for it to play a role in carcinogenesis.61

In this study, we used three methods to detect or represent HPV directly or indirectly in the tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma tissue, and the positive rate ranged from 43 to 75%. In comparison with previous reports,26, 27, 28, 29, 30 our findings are consistent with these reports and it seems that there are no differences between Caucasian and non-Caucasian patients, which is different from the results of Li et al.34 Comparing the HPV-positive rate detected by similar PCR methods, it is significantly different in oral and tonsillar malignancies (41.7 vs 75.0%, P<0.001).5 This difference was also noted in previous articles27, 29, 30, 31 and in a more recent review article.62 This finding may be associated with anatomic site specificity. Like the cervix and anus,63 where squamous cell carcinomas are also highly associated with HPV, transitional zones between different epithelial linings exist in the tonsillar area. Perhaps under these circumstances, the basal cell and the basal extracellular matrix (which are thought to be HPV receptors64) are more likely to be exposed and infected by environmental HPV. According to our data and previous articles, we therefore believe that the anatomic site rather than ethnicity may influence the biological pathways of HPV-induced mucosal cancer.

In our study, irrespective of the method we used, HPV-positive tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma was more likely to occur in patients without alcohol, cigarette, and betel nut usage than HPV-negative tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma. Similar results have been proven by other reports.30, 65, 66 This may imply that in tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma patients who live relatively ‘healthier’ lifestyles, carcinogenesis may be associated with HPV. Although some studies have found associations between advanced TNM staging and HPV positivity, these findings have been somewhat inconsistent. HPV-positive tumors tend to have non-keratinizing histology (Figure 4a and b),30, 65, 67, 68 a point also demonstrated in our study. Using the methods of high-risk HPV in situ hybridization and immunostaining of p16INK4A, our data, like previous reports,28, 29, 30, 69 disclosed a better 5-year survival in HPV-positive tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma than HPV-negative tumors. Multivariate analysis also showed positive high-risk HPV detection (in situ hybridization), or expression of related proteins, (immunostaining of p16INK4A) to be one of the most important independent prognostic factors. The reason for the favorable prognosis in patients with HPV-positive tumors is still unclear. Some studies proved E6-related degradation of p53 in HPV-positive cancers may be functionally inequivalent to HPV-negative p53 mutations,70, 71 and therefore, HPV-positive cancers may have an intact apoptotic response to radiation and chemotherapy.72 On the other hand, in vitro cell line studies have revealed that HPV oncoproteins E6 and E7 mediate suppression of NF-κB transcriptional activity; this may contribute to HPV escape from the immune system in cases of HPV-related carcinogenesis and poor tumor cell recovery after radiation and chemotherapy.73

A prophylactic vaccine composed of the HPV16 viral capsid protein has recently been shown to prevent persistent HPV16 infection and development of cervical dysplasia in phase three randomized controlled trials,74, 75 but the trials have not included the evaluation of head and neck HPV infection. Data on the influence of head and neck HPV infection under immunization are limited to canine and hamster models,76, 77 which did show protective effects and a reduction in the development of HPV-positive lesions. If vaccines can give HPV-related tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma the same protective effect, we then have to tackle the HPV-negative neoplasms with unfavorable prognoses, and the problem of finding vaccines with sustained efficacy against other high-risk HPV serotypes.

Recent reports suggest that HPV-positive tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma should be viewed as a unique subset and the diagnosis of HPV-positive tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma should be considered in all squamous cell carcinoma that arise from the head and neck.26, 28, 30, 62 In this study, in addition to nested PCR, we used the immunostaining of p16INK4A and commercialized autostainer for in situ hybridization to detect most high-risk HPV in tumor tissue, and compared the clinical and prognosis data. According to our results, although the nested PCR method had the highest HPV detection rate, it alone may be too sensitive to make a reliable prognostic prediction. Similar results are seen using real-time PCR. In 58 HPV16(+) cases detected with nested PCR, 18 cases (31%) had low viral copy numbers when real-time PCR was used to quantitate the HPV16 viral load. On the other hand, high-risk HPV in situ hybridization and immunostaining of p16INK4A seem more clinically suited to provide us with reliable prognostic data. Weinberger and Psyrri recently reported similar results in cases of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma.69 In their series, all cases except one with overexpression of p16INK4A were noted in their HPV(+) group, and the only case with overexpression of p16INK4A noted in their HPV(−) group was excluded from their statistical analysis. They concluded that only the HPV+/p16 high group had a favorable prognosis.69 We think that using real-time PCR or nested PCR alone for the detection of HPV DNA may not provide reliable results. Although not included in their statistical analysis, we believe that overexpression of p16INK4A alone could served as a reliable prognostic marker in Weinberger and Psyrri's series, which had results similar to ours. p16INK4A expression has been considered a surrogate biomarker for HPV-related cervical and vulvar cancers.48, 49, 50 Recent literature26, 69 and our data (positive predict value for HPV was 91.8%) also confirmed this phenomenon in tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma, despite there being a few HPV(−) cases overexpressing p16INK4A. A proportion of non-HPV-related human malignancies also overexpress p16INK4A, for example, some endometrioid adenocarcinoma, endometrial and ovarian serous carcinoma, and urothelial carcinoma.78, 79, 80 This suggests that there should be some other types of control mechanisms, in addition to those described above, that can induce overexpression of p16INK4A. In our data, a few cases with integrated HPV DNA did not overexpress p16INK4A. A similar situation was reported in cervical cancer cells with p16 promoter hypermethylation leading to abrogation of p16INK4A.81 Although a few exceptions in the association between p16INK4A overexpression and HPV positivity have been noted, it does not influence the status of p16INK4A as a prognostic predictive maker for primary tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma and high-risk HPV in situ hybridization, as well as its importance in providing accurate prognostic information to allow for adequate treatment.

References

Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin 2006;56:106–130.

Lingen M, Sturgis EM, Kies MS . Squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in nonsmokers: clinical and biologic characteristics and implications for management. Curr Opin Oncol 2001;13:176–182.

Department of Health, The Executive Yuan, ROC. Cancer registry annual report in Taiwan area, 2002. Department of Health, The Executive Yuan: Taipei, ROC, 2007.

Ko YC, Huang YL, Lee CH, et al. Betel quid chewing, cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption related to oral cancer in Taiwan. J Oral Pathol Med 1995;24:450–453.

Chang JY, Lin MC, Chiang CP . High-risk human papillomaviruses may have an important role in non-oral habits-associated oral squamous cell carcinomas in Taiwan. Am J Clin Pathol 2003;120:909–916.

Kuriakose M, Sankaranarayanan M, Nair MK, et al. Comparison of oral squamous cell carcinoma in younger and older patients in India. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol 1992;28:450–453.

Myers JN, Elkins T, Roberts D, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue in young adults: increasing incidence and factors that predict treatment outcomes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000;1222:44–51.

Atula S, Grenman R, Laippala P, et al. Cancer of the tongue in patients younger than 40 years: a distinct entity? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996;122:1313–1319.

Young SK, Min KW . In situ DNA hybridization analysis of oral papillomas, leukoplakias, and carcinomas of human papillomavirus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1991;71:726–729.

Brandwein M, Zeitlin J, Nuovo GJ, et al. HPV detection using ‘hot start’ polymerase chain reaction in patients with oral cancer: a clinicopathological study of 64 patients. Mod Pathol 1994;61:450–454.

Balaram P, Nalinakumari KR, Abraham E, et al. Human papillomaviruses in 91 oral cancers from Indian betel quid chewers: high prevalence and multiplicity of infections. Int J Cancer 1995;61:450–454.

Cruz IB, Snijders PJ, Steenbergen RD, et al. Age-dependence of human papillomavirus DNA presence in oral squamous cell carcinomas. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol 1996;32:55–62.

Miller CS, White DK . Human papillomavirus expression in oral mucosa, premalignant conditions, and squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1996;82:57–68.

Sugerman PB, Shillitoe EJ . The high risk human papillomaviruses and oral cancer: evidence for and against a causal relationship. Oral Dis 1997;3:130–147.

Elamin F, Steingrimsdottir H, Wanakulasuriya S, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus infection in premalignant and malignant lesions of the oral cavity in UK subjects: a novel method of detection. Oral Oncol 1998;34:191–197.

Mckaig RG, Baric RS, Olshan AF . Human papillomavirus and head and neck cancer: epidemiology and molecular biology. Head Neck 1998;20:250–265.

Aggelopoulou EP, Skarlos D, Papadimitriou C, et al. Human papilloma virus DNA detection in oral lesions in the Greek population. Anticancer Res 1999;19:1391–1395.

Badaracco G, Venuti A, Morello R, et al. Human papillomavirus in head and neck carcinomas: prevalence, physical status and relationship with clinical/pathological parameters. Anticancer Res 2000;20:1301–1305.

Bouda M, Gorgoulis VG, Kastrinakis NG, et al. High risk' HPV types are frequently detected in potentially malignant and malignant oral lesions, but not in normal oral mucosa. Mod Pathol 2000;13:644–653.

Uobe K, Masuno K, Fang YR, et al. Detection of HPV in Japanese and Chinese oral carcinomas by in situ PCR. Oral Oncol 2001;37:146–152.

Miller CS, Johnstone BM . Human papillomavirus as a risk factor for oral squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis, 1982–1997. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2001;91:622–635.

Ritchie JM, Smith EM, Summersgill KF, et al. Human papillomavirus infection as a prognostic factor in carcinomas of the oral cavity and oropharynx. Int J Cancer 2003;104:336–344.

Zoltan S, Imre S, Ildiko B . Causal association between human papillomavirus infection and head and neck and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Hung Oncol 2002;46:35–41.

Li W, Thompson CH, Cossart YE, et al. The site of infection and ethnicity of the patient influence the biological pathways to HPV-induced mucosal cancer. Mod Pathol 2004;17:1031–1037.

Yang YY, Koh LW, Tsai JH, et al. Involvement of viral and chemical factors with oral cancer in Taiwan. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2004;34:176–183.

Li W, Thompson CH, Cossart YE, et al. The expression of key cell cycle markers and presence of human papillomavirus in squamous cell carcinoma of the tonsil. Head Neck 2004;26:1–9.

Kreimer AR, Clifford GM, Boyle P, et al. Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14:467–475.

Li W, Thompson CH, O'Brien CJ, et al. Human papillomavirus positivity predicts favourable outcome for squamous carcinoma of the tonsil. Int J Cancer 2003;106:553–558.

Ringstrom E, Peters E, Hasegawa M, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 and squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res 2002;8:3187–3192.

Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, et al. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:709–720.

Herrero R CX, Pawlita M, Lissowska J, et al, IARC Multicenter Oral Cancer Study Group. Human papillomavirus and oral cancer: the International Agency for Research on Cancer multicenter study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003;95:1772–1783.

Herrero R . Chapter 7: Human papillomavirus and cancer of the upper aerodigestive tract. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2003;31:47–51.

Andl T, Kahn T, Pfuhl A, et al. Etiological involvement of oncogenic human papillomavirus in tonsillar squamous cell carcinomas lacking retinoblastoma cell cycle control. Cancer Res 1998;58:5–13.

Li W, Thompson CH, Xin D, et al. Absence of human papillomavirus in tonsillar squamous cell carcinomas from Chinese patients. Am J Pathol 2003;163:2185–2189.

Durst M, Dzarlieva-Petrusevska RT, Boukamp P, et al. Molecular and cytogenetic analysis of immortalized human primary keratinocytes obtained after transfection with human papillomavirus type 16 DNA. Oncogene 1987;1:251–256.

Park NH, Min BM, Li SL, et al. Immortalization of normal human oral keratinocytes with type 16 human papillomavirus. Carcinogenesis 1991;12:1627–1631.

Sexton CJ, Proby CM, Banks L, et al. Characterization of factors involved in human papillomavirus type 16-mediated immortalization of oral keratinocytes. J Gen Virol 1993;74:755–761.

Oda D, Bigler L, Lee P, et al. HPV immortalization of human oral epithelial cells: a model for carcinogenesis. Exp Cell Res 1996;226:164–169.

Brehm A, Kouzarides T . Retinoblastoma protein meets chromatin. Trends Biochem Sci 1999;24:142–145.

Jones DL, Munger K . Interactions of the human papillomavirus E7 protein with cell cycle regulators. Semin Cancer Biol 1996;7:327–337.

Stoler MH . Human papillomavirus and cervical neoplasia: a model for carcinogenesis. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2000;19:16–28.

Zerfass-Thome K, Zwerschke W, Mannhardt B, et al. Inactivation of the cdk inhibitor p27KIP1 by the human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein. Oncogene 1996;13:2323–2330.

zur Hausen H . Molecular pathogenesis of cancer of the cervix and its causation by specific human papillomavirus types. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 1994;186:131–156.

Dyson N, Howley PM, Munger K, et al. The human papilloma virus-16 E7 oncoprotein is able to bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Science 1989;243:934–937.

Sherr CJ . Cancer cell cycles. Science 1996;274:1672–1677.

Kamb A, Gruis NA, Weaver-Feldhaus J, et al. A cell cycle regulator potentially involved in genesis of many tumor types. Science 1994;264:436–440.

Khleif SN, DeGregori J, Yee CL, et al. Inhibition of cyclin D–CDK4/CDK6 activity is associated with an E2F-mediated induction of cyclin kinase inhibitor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996;93:4350–4354.

Keating JT, Cviko A, Riethdorf S, et al. Ki-67, cyclin E, and p16INK4 are complimentary surrogate biomarkers for human papilloma virus-related cervical neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:884–891.

Riethdorf S, Neffen EF, Cviko A, et al. p16INK4A expression as biomarker for HPV 16-related vulvar neoplasias. Hum Pathol 2004;35:1477–1483.

Kalof AN, Evans MF, Simmons-Arnold L, et al. p16INK4A immunoexpression and HPV in situ hybridization signal patterns: potential markers of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:647–649.

Peitsaro P, Johansson B, Syrjänen S . Integrated human papillomavirus type 16 is frequently found in cervical cancer precursors as demonstrated by a novel quantitative real-time PCR technique. J Clin Microbiol 2002;40:886–891.

Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, et al. Head and Neck Tumor. IARC: Lyon.

Tringler B, Gup CJ, Singh M, et al. Evaluation of p16INK4a and pRb expression in cervical squamous and glandular neoplasia. Hum Pathol 2004;35:689–696.

Bauer HM, Greer CE, Manos MM . Determination of genital human papillomavirus infection by consensus PCR amplification. Herrington CS, McGee JO (eds). Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Feoli-Fonseca JC, Oligny LL, Filion M, et al. Direct human papillomavirus (HPV) sequencing method yields a novel HPV in a human immunodeficiency virus-positive Quebec woman and distinguishes a new HPV clade. J Infect Dis 1998;178:1492–1496.

Feoli-Fonseca JC, Oligny LL, Filion M, et al. A two-tier polymerase chain reaction direct sequencing method for detecting and typing human papillomaviruses in pathological specimens. Diagn Mol Pathol 1998;7:317–323.

Feoli-Fonseca JC, Oligny LL, Filion M, et al. A putative novel human papillomavirus identified by PCR-DS. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1998;250:63–67.

Jacobs MV, Snijders PJ, van den Brule AJ, et al. A general primer GP5+/GP6(+)-mediated PCR-enzyme immunoassay method for rapid detection of 14 high-risk and 6 low-risk human papillomavirus genotypes in cervical scrapings. J Clin Microbiol 1997;35:791–795.

Huang H, Huang SL, Lin CY, et al. Human papillomavirus genotyping by a polymerase chain reaction-based genechip method in cervical carcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus radical surgery. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2004;14:639–649.

Arias-Pulido H, Peyton CL, Joste NE, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 integration in cervical carcinoma in situ and in invasive cervical cancer. J Clin Microbiol 2006;44:1755–1762.

Gillison ML, Shah KV . Chapter 9: Role of mucosal human papillomavirus in nongenital cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2003;31:57–65.

Fakhry C, Gillison ML . Clinical implications of human papillomavirus in head and neck cancers. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2606–2611.

Gervaz P, Hirschel B, Morel P . Molecular biology of squamous cell carcinoma of the anus. Br J Surg 2006;93:531–538.

Culp TD, Budgeon LR, Christensen ND . Human papillomaviruses bind a basal extracellular matrix component secreted by keratinocytes which is distinct from a membrane-associated receptor. Virology 2006;347:147–159.

Haraf DJ, Nodzenski E, Brachman D, et al. Human papilloma virus and p53 in head and neck cancer: clinical correlates and survival. Clin Cancer Res 1996;2:755–762.

Lindel K, Beer KT, Laissue J, et al. Human papillomavirus positive squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: a radiosensitive subgroup of head and neck carcinoma. Cancer 2001;92:805–813.

El-Mofty SK, Lu DW . Prevalence of human papillomavirus type 16 DNA in squamous cell carcinoma of the palatine tonsil, and not the oral cavity, in young patients: a distinct clinicopathologic and molecular disease entity. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:1463–1470.

Poetsch M, Lorenz G, Bankau A, et al. Basaloid in contrast to nonbasaloid head and neck squamous cell carcinomas display aberrations especially in cell cycle control genes. Head Neck 2003;25:904–910.

Weinberger PM, Yu Z, Haffty BG, et al. Molecular classification identifies a subset of human papillomavirus—associated oropharyngeal cancers with favorable prognosis. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:736–747.

Butz K, Whitaker N, Denk C, et al. Induction of the p53-target gene GADD45 in HPV-positive cancer cells. Oncogene 1999;18:2381–2386.

Huang H, Li CY, Little JB . Abrogation of P53 function by transfection of HPV16 E6 gene does not enhance resistance of human tumour cells to ionizing radiation. Int J Radiat Biol 1996;70:151–160.

Ferris RL, Martinez I, Sirianni N, et al. Human papillomavirus-16 associated squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (squamous cell carcinomaHN): a natural disease model provides insights into viral carcinogenesis. Eur J Cancer 2005;41:807–815.

Spitkovsky D, Hehner SP, Hofmann TG, et al. The human papillomavirus oncoprotein E7 attenuates NF-kappa B activation by targeting the Ikappa B kinase complex. J Biol Chem 2002;277:25576–25582.

Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler CM, et al, HPV Vaccine Study Group. Sustained efficacy up to 4.5 years of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine against human papillomavirus types 16 and 18: follow-up from a randomised control trial. Lancet 2006;367:1247–1255.

Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler C, et al, GlaxoSmithKline HPV Vaccine Study Group. Efficacy of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine in prevention of infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;364:1757–1765.

Maeda H, Kubo K, Sugita Y, et al. DNA vaccine against hamster oral papillomavirus-associated oral cancer. J Int Med Res 2005;33:647–653.

Johnston KB, Monteiro JM, Schultz LD, et al. Protection of beagle dogs from mucosal challenge with canine oral papillomavirus by immunization with recombinant adenoviruses expressing codon-optimized early genes. Virology 2005;336:208–218.

Ansari-Lari MA, Staebler A, Zaino RJ, et al. Distinction of endocervical and endometrial adenocarcinomas: immunohistochemical p16 expression correlated with human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA detection. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:160–167.

O'Neill CJ, McCluggage WG . p16 expression in the female genital tract and its value in diagnosis. Adv Anat Pathol 2006;13:8–15.

Shariat SF, Tokunaga H, Zhou J, et al. p53, p21, pRB, and p16 expression predict clinical outcome in cystectomy with bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:1014–1024.

Nuovo GJ, Plaia TW, Belinsky SA, et al. In situ detection of the hypermethylation-induced inactivation of the p16 gene as an early event in oncogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999;96:12754–12759.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Taiwan University Hospital Research Grant no. NTUH 95–309. The study has not been presented elsewhere. We thank Taiwan Molecular Diagnostic Laboratories Ltd for the kind donation of plasmid pHPV16.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Conflict of interest

The authors indicated have no potential conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kuo, KT., Hsiao, CH., Lin, CH. et al. The biomarkers of human papillomavirus infection in tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma—molecular basis and predicting favorable outcome. Mod Pathol 21, 376–386 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800979

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800979

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Rising incidence of HPV positive oropharyngeal cancer in Taiwan between 1999 and 2014 where betel nut chewing is common

BMC Cancer (2022)

-

HPV RNA CISH score identifies two prognostic groups in a p16 positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma population

Modern Pathology (2018)

-

Betel nut chewing history is an independent prognosticator for smoking patients with locally advanced stage IV head and neck squamous cell carcinoma receiving induction chemotherapy with docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil

World Journal of Surgical Oncology (2016)

-

Relationship between HPV and the biomarkers annexin A1 and p53 in oropharyngeal cancer

Infectious Agents and Cancer (2014)

-

Correlation between human papillomavirus and p16 overexpression in oropharyngeal tumours: a systematic review

British Journal of Cancer (2014)