Abstract

Porous structure of reduced graphene oxide (rGO) plays an important role in developing flexible graphene-based devices. In this work, we report a novel methodology for reduction of freestanding graphite oxide (GO) sheet by picosecond pulse laser direct writing in liquid nitrogen. Non-agglomerate and porous structure of rGO is fabricated successfully due to frozen effect during laser processing. Compared with laser-irradiated rGO developed in N2 gas at ambient environment, the frozen rGO developed in liquid N2 shows better ordered structure with less defects, crack-free morphology as well as better electron supercapacitor performance including 50–60 Ω/sq in sheet electrical resistance. Mechanism of cryotemperature photoreduction GO is also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reduction of graphite oxide (GO) has been well developed to produce graphene-based devices with novel electronic properties1,2,3,4. Various methods including chemical reaction, thermal treatment, photo-chemical reaction and laser reduction techniques have been applied to remove the oxygen species for reduction of GO and the typical methods have been summarized in Table 1 to make a clear comparison of overall characteristics for GO reduction5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Laser reduction of GO has been recognized as a flexible way to produce reduced graphene oxide (rGO) for flexible patterning and integration of devices5,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. A variety of laser-irradiated GO methods have been reported and most of them can be simply classified into two categories: The first is reduction of GO solution12,13,14,15 and the second is reduction and patterning of GO film with solid-state substrate17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26.

In order to improve mechanical properties of laser-irradiated rGO and avoid the limitation of temperature sensitive substrate for mass scalable devices, laser reduction of free standing GO sheet has attracted much attention. Koratka’s group reported CO2 laser-reduced freestanding GO sheet with thickness 10–20 μm as high-rate capable anodes for lithium-ion batteries and found that the irradiated rGO with C/O ratio of 10.1 had defects including micrometer-scale pores, cracks and intersheet voids25. Sokolov26 described reduction of freestanding GO sheet with thickness 5–8 μm to multilayer graphene using excimer laser irradiation in oxygen-free environments and claimed that the best sheet resistance could be 100 Ω/sq and C/O ratio was 40. However, agglomeration of these rGO usually occurs because they are easily clustered at room temperature or above, which largely affects the electronic performance.

The aim of this paper is to provide a novel design for the reduction of freestanding GO sheet by one-stop photoreduction using a picosecond pulse laser. GO sheet was immersed in liquid nitrogen at −196 °C during laser irradiation to frozen the irradiated surface. The thickness of current freestanding GO sheet is measured as 20–30 μm, which is suitable for mechanically robust devices. The oxygen removal, ordered structure and electrical performance of cryotemperature photoreduction of GO sheet were examined. Special attention is paid to understand the mechanism of cryotemperature photoreduction through comparison in normal N2 gas and liquid N2 conditions.

Results

Figure 1 shows Raman spectra of both GO and rGO before and after laser irradiation. Optical images show individual measured area of all samples and the scale bar is 10 micron. It is known that the G and D bands result from E2g phonon scattering of graphitic structure and vibrations of carbon atoms with dangling bonds in plane terminations of disordered graphite12, while the 2D-band is highly sensitive to stacking the graphene layers as the second order of the D-peak19. The presence of 2D-band at 2708 cm−1 indicates the considerable reduction of graphene oxides19. Quantitative results were summarized in Table 2. The overall changes in the D-band and G-band including narrowing and decrease in peak intensity as well as peak shift shows high ordered structure and production of graphene features in both laser irradiated rGO, which is in excellent agreement with previous findings12,14,21,22,24. More shift in the position for rGO in N2 gas compared to rGO in liquid N2 is mainly ascribed to the combined effect of remaining oxygen species after the reduction, defects associated with edge scattering in the rGO sheets as well as possible doping of rGO due to the presence of liquid N2 during laser process15,27.

The D/G intensity ratio (ID/IG) reduced significantly from 0.82 to 0.43 in N2 gas and 0.27 in liquid N2, respectively. This is supported by Mortazavi who reported the ratio of D to G-band (ID/IG) was about 0.5 based on nanosecond pulse laser ablation of graphite target28. The current ID/IG ratio is also comparable with laser reduction of GO film with solid substrate19,25. It should be noted that ID/IG ratios of rGO from liquid N2 are much lower than the value obtained from laser reduction of GO solution14,15,16,17,18. Such discrepancy as well as the difference between irradiation in N2 gas and in liquid N2 may correspond to photothermal and photochemical reduction between solid-state GO and GO solution during laser irradiation12. In addition, the change of ID/IG ratio offers a powerful evidence of N doping in rGO (N-rGO). According to the findings of Youn27 and Chen29, lower ID/IG ratio of N-rGO compared to that of rGO was attributed to the electron-donating capability of an N-heteroatom-induced graphitic degree decrease as well as nitrogen doping generates the decrease in the defects of high-surface-area N-rGO. Further investigation for the possible doping of rGO by XPS and XRD is needed.

It should be noted that temperature change caused by performing Raman measurement may occur at rGO sample surface, which can in turn alter the FWHM and frequency of the 2D and G bands12,19,30. In this work, however, we claim that the lattice change of rGO both in N2 gas and in liquid N2 is not remarkable, which might be due to the lower chance of having a significant radical temperature gradient effect on current rGO sample with thickness more than 20 micron30.

To examine surface morphology and chemistry analysis of the irradiated rGO developed both in N2 gas and in liquid N2, all irradiated regions were characterized by SEM/EDS and AFM, as shown in Figs 2 and 3. Plate-shape and crack-like structure was observed in Fig. 2(a,b), indicating that GO sheet expansion took place during laser processing. No cracks, holes or voids was found in the microstructure after laser irradiation in liquid N2. Figure 2(d,e) show that periodic line-shape structure with average width of 100 μm was formed and porous structure within line-shape between peaks and valleys was observed. Compared with the plate-shape structure in Fig. 2(b), the porous structure with clear edges among each layer in Fig. 2(e) are much looser, which might mainly due to frozen effect during laser irradiation at low temperature condition. The result is also consistent with what was previously reported about Raman analysis of high-surface-area N-rGO27. EDS line scan indicates distribution of main elements carbon and oxygen in the as received GO sheet and laser-irradiated rGO regions. Figure 2(c,f) show that carbon content was significant increased while oxygen content was decreased correspondingly at both top surfaces of rGO structure. It is interesting to find that both carbon and oxygen content drops at the valley of periodic structure, which may be related to detector limitation of EDS. Both AFM measurement areas were indicated in Fig. 2(b,e). The surface topograghy of these rGO structure was further measured in Fig. 3. It can be found that the surface in liquid N2 is rougher than that of N2 gas from both 3D images and 2D profilers and the distance between the peaks and valleys was measured as around 600 nm. Compared with clustered structure in Fig. 3(a), the porous structure with clear edges could be found in Fig. 3(b).

Surface chemistry of both rGO was further analyzed by XPS and the quantitative results were summarized in Table 3. It shows C-C, C-O and C = O reduced from 38.5%, 26.7%, 6.9% in GO to 67.4%, 19.5%, 5.1% in rGO of N2 gas and 75.3%, 12.3%, 3.6% in rGO of liquid N2, respectively, indicating that most of oxygen-containing functional groups have been removed after laser irradiation. The C/O ratio of as-received GO was calculated as 2.4, while the C/O ratio of the irradiated rGO rapidly increased as 9.1 in N2 gas and 10.3 in liquid N2. These results are consistent with the Raman analysis.

Therefore, we propose that the reduction of GO is improved in liquid N2 during laser irradiation, compared to that of N2 gas. The current C-C percentage is higher than nanosecond pulse laser irradiated in air with shorter wavelength, but lower than both nanosecond pulse laser irradiated in vacuum and femtosecond pulse laser irradiated in air with shorter wavelength, according to reduction degree of solid-state photoreduction in the literature12,18,25,26,28,31. The C/O ratio is lower than nanosecond pulse laser irradiated in air or in vacuum with shorter wavelength, but higher than that of CO2 laser. Correspondingly, we propose that cryotemperature photoreduction is not critical in restoring sp2 carbon network of GO by C-C peak and the C/O ratio, while laser wavelength plays more important role either by photoreduction or photochemical reduction.

The original graphite oxide sheet is completely insulating with sheet resistance values higher than >20 MΩ/sq using four-point probe measurements. After one-stop laser scanning in current work, the sheet resistance values of the irradiated rGO region were reduced to 104 Ω/sq in N2 gas and 50–60 Ω/sq in liquid N2, which is even lower than the best values as 100–500 Ω/sq reported by Sokolov26. The electrochemical behaviors of both rGO was further examined in Fig. 4. The scan range was optimized due to different current density and charge-discharge time. Figure 4(a,b) show poor performance for electrochemical performance of rGO sample in N2 gas. The specific capacitance (Csc) was measured to be 4 F/g at current density of 1 A/g and it was reduced to 3.0 F/g, 1.71 F/g, 1.14 F/g, when the current density increased to 2 A/g, 4 A/g and 6 A/g correspondingly. For rGO sample in liquid N2, the nearly rectangular CV shape at different scan rates indicates an enhanced electrochemical performance, which is indicative of potential capacitive behavior, as shown in Fig. 4(c). Figure 4(d) shows that the galvanostatic charge/discharge curves of rGO are linear and symmetric. Csc was measured to be 140 F/g at current density of 1 A/g. When the current density increased to 2, 4 and 6 A/g, Csc was reduced to 61.2, 33.2, 21.2 and 12.4 F/g, correspondingly. Our results need to be further improved including the optimization of laser parameters including energy density, overlapping ratio, repetition rate, scanning speed, etc.

Electrochemical performance of rGO in both N2 gas and liquid N2.

(a) CV profiles of rGO in N2 gas at different scan rates of 40, 60, 80 and 100 mV/s; (b) Galvanostatic charge/discharge curves of rGO in N2 gas at different current density of 1, 2, 4, 6 A/g; (c) CV profiles of rGO in liquid N2 at different scan rates of 40, 60, 80 and 100 mV/s; (d) Galvanostatic charge/discharge curves of rGO in liquid N2 at different current density of 1, 2, 4, 6 A/g.

Discussion

During ultrashort pulse laser process, strong excitation of material surface leads to rapid ejection of species, such as electrons, photons or atoms and the excited species will transfer energy to the lattice by typical electron-photon coupling30. Due to long wavelength irradiation, incident light at high fluence would create heat at the surface of GO sheet. It is generally accepted that plasma expansion driven by pressure and temperature difference above the irradiated surface is accompanied by emission of shock waves. However, heat conduction and GO sheet expansion was depressed in liquid nitrogen, thus plasma expansion and above surface plume interactions would be slightly different due to higher density gradient and more effective collisional cooling32. Furthermore, cryotemperature photoreduction of GO sheet and heat depression as well as frozen effect took place simultaneously in this work, thereby more accessible energy of laser imparts to the irradiated surface for ablation than thermal effect. The attractive force between the GO sheet and liquid nitrogen would arise from the nature of instantaneous fluctuating moments. Correspondingly, rapid evaporation occurred within the focal volume based on the intense molecular vibrational/rotational excitations26. The internal pressure between the layers exceeds up to overcome the lattice bonding energy within the freestanding GO sheet with thickness of 20–30 μm. This may explain the reason for frozen structure with crack free and porous structure of rGO development.

We suggest that depressed plasma expansion and frozen effect in liquid N2 accelerates the formation of energetic species in freestanding GO sheet by loosening the lattice bonds, resulting in more ordered state with fewer defects by photochemical desorption of oxygen groups and excellent sheet resistance and electrochemical properties of the irradiated rGO, compared with that of N2 gas background.

Conclusions

We have proposed a novel design methodology for one-stop laser photoreduction of freestanding GO sheet. In specific, we have experimentally demonstrated the feasibility of cryotemperature rGO fabricated by picosecond pulse laser at liquid N2 condition, which enables promising electrical performance including the drop of sheet resistance by a factor of 104 to 105. Compared with plate-shape and crack-like structure of rGO developed in N2 gas, the frozen laser-irradiated rGO have crack-free porous structure mainly due to cryotemperature development and depressed thermal expansion, while the patterning parameters can be further tailored. Chemical analyses showed that the photochemical desorption of oxygen groups with better ordered structure and less defects on basis of 2D-band at 2708 cm−1, ID/IG ratio as 0.27 and C/O ratio as 10.3. On basis of widely used commercial picosecond pulse laser, this proof-of-concept process has the potential to effectively improve the development of manufacturing processes for flexible devices including roll-up displays, wearable devices and implantable biodevices1,12.

Methods

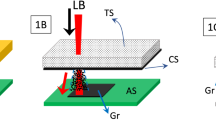

In this work, the freestanding GO sheet was synthesized from modified chemical method27. Briefly, GO dispersion was exfoliated from graphite oxide through extensive ultrasonication and placed in a casting mold made of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE). Correspondingly, the freestanding GO sheet was peeled off from the PTFE substrate after water was completely evaporated from the dispersion. The size of GO sheet in this work was 50 mm × 50 mm at thickness of 20–30 μm. A picosecond pulsed laser (wavelength 1064 nm, pulse duration 10 ps, repetition rate 100 000 Hz, spot size 30 μm) was used. The energy density was varied from 0.1 to 0.4 J/cm2 and scanning speed was changed in the range of 10–100 mm/s. The irradiated area was 10 × 10 mm2 in square using hatched scanning mode with 50% overlapping in the program. When laser was turned on, the specimen was placed in a well-sealed chamber filled with high purity nitrogen gas and liquid nitrogen, respectively, as shown in Fig. 5. No substrate under the GO sheet was provided. After laser exposure in liquid N2, the residual liquid N2 was evaporated at the room temperature.

Raman spectra were performed by a WITEC alpha 300 R Confocal Raman system in air ambient environment (532 nm excitation wavelength and 0.02 cm−1 spectral resolution). The Raman emission was collected by an Olympus 50× objective for better signal-to-noise ratio and the excitation laser was set low power to prevent potential structure damages. Each measurement of Raman spectra was performed at 5 specimens for individual sample of GO, rGO in N2 gas and rGO in liquid N2, respectively. Microstructural features of irradiated areas were investigated using Carl Zeiss EVO 50 scanning electron microscopy (SEM), equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS). The EDS measurements provided information on chemical composition. Surface topography of the irradiated areas was measured using Atomic Force Microscope (Bruker, Dimension FastScan).The non-contact mode is used to image 2D/3D profile and measure roughness of the textured surfaces. XPS analysis was carried out for the surface chemistry using Thermo Scientific Theta Probe XPS. Monochromatic Al Ka X-ray (hν = 1486.6 eV) was employed for analysis at an incident angle of 30° with respect to the surface normal. Photoelectrons are collected at a take-off angle of 50° with respect to the surface normal. The analyzed area is approximately 400 μm in diameter. Survey spectra and high-resolution spectra were acquired for surface composition analysis and chemical state identification, respectively. Sheet resistance measurements were performed by conventional four-point probe station using Keithley DMM source meter instrument at ambient conditions. Moreover, all electrochemical experiments were performed with CHI 660D electrochemical workstation. A three-electrode configuration was employed for all of the measurements with a platinum foil counter electrode and saturated calomel electrode (SCE) reference electrode. The working electrodes used was laser-reduced rGO, which was cut from the irradiated GO specimen. 0.5 M Na2SO4 was used as the electrolyte and the potential scan was chosen in the range of −0.8 V and −0.2 V.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Guan, Y. C. et al. Fabrication of Laser-reduced Graphene Oxide in Liquid Nitrogen Environment. Sci. Rep. 6, 28913; doi: 10.1038/srep28913 (2016).

References

Loh, K. P., Bao, Q. L., Eda, G. & Chhowalla, M. Graphene oxide as a chemically tunable platform for optical applications. Nat. Chem. 2, 1015–1024 (2010).

Zhu, Y. W. et al. Carbon-based supercapacitors produced by activation of graphene. Science 332, 1537–1541 (2011).

Qi, X. Y. et al. Graphene oxide as a novel nanoplatform for enhancement of aggregation-induced emission of silole fluorophores. Adv. Mater. 24, 4191–4195 (2012).

Kim, S., Yoo, Y., Kim, H., Lee, E. & Lee, J. Y. Reduction of graphene oxide/alginate composite hydrogels for enhanced adsorption of hydrophobic compounds. Nanotechnol . 26, 405602 (2015).

Chua, C. K. & Pumera, M. Chemical reduction of graphene oxide: a synthetic chemistry viewpoint. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 291–312 (2014).

Das, A. K. et al. Iodide-mediated room temperature reduction of graphene oxide: a rapid chemical route for the synthesis of a bifunctional electrocatalyst. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 1332–1340 (2014).

Larciprete, R. et al. Dual path mechanism in the thermal reduction of graphene oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 17315–17321 (2011).

Xu, C. L. et al. Can in situ thermal reduction be a green and efficient way in the fabrication of electrically conductive polymer/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites? Composites: Part A 53, 24–33 (2013).

Akhavan, O., Abdolahad, M., Esfandiar, A. & Mohatashamifar, M. Photodegradation of graphene oxide sheets by TiO2 nanoparticles after a photocatalytic reduction. J. Phys. Chem. C. 114, 12955–12959 (2010).

Akhavan, O. Bacteriorhodopsin as a superior substitute for hydrazine in chemical reduction of single-layer graphene oxide sheets. Carbon 81, 158–166 (2015).

Sokolov, D. A., Rouleau, C. M., Geohegan, D. B. & Orlando, T. M. Excimer laser reduction and patterning of graphite oxide. Carbon 53, 81–89 (2013).

Zhang, Y. L. et al. Photoreduction of graphene oxides: methods, properties and applications, Adv. Opt. Mater. 2, 10–28 (2014).

Abdelsayed, V. et al. Photothermal deoxygenation of graphite oxide with laser excitation in solution and graphene-aided increase in water temperature, J. Phys. Chem. Lett 1, 2804–2809 (2010).

Trusovas, R. et al. Reduction of graphite oxide to graphene with laser irradiation, Carbon 52, 574–582 (2013).

Ghadim, E. E. et al. Pulsed laser irradiation for environment friendly reduction of graphene oxide suspensions. Appl. Surf. Sci. 301, 183–188 (2014).

Zheng, X. R., Jia, B. H., Chen, X. & Gu, M. In situ third-order nonlinear responses during laser reduction of graphene oxide thin films towards on-chip nonlinear photonic devices, Adv. Mater. 26, 2699–2703 (2014).

Gao, W. et al. Direct laser writing of micro-supercapacitors on hydrated graphite oxide films. Nat. Nano . 6, 496–500 (2011).

Petridis, C. et al. Post-fabrication, in situ laser reduction of graphene oxide devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 093115 (2013).

Yung, K. C. et al. Laser direct patterning of a reduced-graphene oxide transparent circuit on a graphene oxide thin film. J. Appl. Phys. 113, 244903 (2013).

Maher, F. E., Veronica, S., Sergey, D. & Richard, B. K. Laser scribing of high-performance and flexible graphene-based electrochemical capacitors. Science 335, 13260–13230 (2012).

Veronica, S. et al. Patterning and electronic tuning of laser scribed graphene for flexible all-carbon devices, ACS Nano 6, 1395–13403 (2012).

Ye, X. H. et al. Direct laser fabrication of large-area and patterned graphene at room temperature. Carbon 68, 784–790 (2014).

Kymakis, E., Petridis, C., Anthopoulos, T. D. & Stratakis, E. Laser-assisted reduction of graphene oxide for flexible, large-area optoelectronics. IEEE J. Sel. Top Quant . 20, 6000410 (2014).

Thekkekara, L. V. et al. On-chip energy storage integrated with solar cells using a laser scribed graphene oxide film. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 031105 (2015).

Mukherjee, R., Thomas, A. V., Krishnamurthy, A. & Koratkar, N. Photothermally Reduced graphene as high-power anodes for lithium-ion batteries. ACS Nano 6, 7867–7878 (2012).

Sokolov, D. A., Rouleau, C. M., Geohegan, D. B. & Orlando, T. M. Excimer laser reduction and patterning of graphite oxide. Carbon 53, 81–89 (2013).

Youn, H. C. et al. High-surface-area nitrogen-doped reduced graphene oxide for electric double-layer capacitors. ChemSusChem 8, 1875–1884 (2015).

Mortazavi, S. Z., Parvin, P. & Reyhani, A. Fabrication of graphene based on Q-switched Nd:YAG laser ablation of graphite target in liquid nitrogen. Laser Phys. 9, 547–552 (2012).

Chen, R. W., Yan, J., Liu, Y. & Li, J. H. Three-dimensional nitrogen-doped graphene/MnO nanoparticle hybrids as a high-performance catalyst for oxygen reduction reaction. Journal of Physical Chemistry C 119, 8032–8037 (2015).

Guan Y. C., Zhou W., Li Z. L. & Zheng H. Y. Femtosecond laser-induced iridescent effect on az31b magnesium alloy surface. J. Phys. D 46, 425305 (2013).

Cong, C. X., Li, K., Zhang, X. X. & Yu T. Visualization of arrangements of carbon atoms in graphene layers by Raman mapping and atomic-resolution TEM. Sci. Rep. 3, 1195 (2012).

Arnold, C. B., Serra, P. & Pique, A. Laser direct-write techniques for printing of complex materials. MRS Bulletin 32, 23–31 (2007).

Acknowledgements

Support by the National Key Basic Research Program of China with grant number 2015CB059900, Beijing Natural Science Foundation with grant number 3162019, Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities from Beihang University with project code 74003401 and A*STAR Collaboration Research Project with project code U13-M-026SU is gratefully acknowledged. The authors special thank Prof. Duan HongWei and Dr. Fang Zheng from Nanyang Technological University for providing GO sheet and electrochemical testing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C.G., H.Y.Z. and M.H.H. initialed the project and conceived and designed the experiments; Y.C.G., Y.W.F. and G.C.L. performed the experiments; Y.C.G. and Y.W.F. collected and analyzed the data and co-wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Guan, Y., Fang, Y., Lim, G. et al. Fabrication of Laser-reduced Graphene Oxide in Liquid Nitrogen Environment. Sci Rep 6, 28913 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28913

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28913

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.