Abstract

Prions are unique infectious agents that replicate without a genome and cause neurodegenerative diseases that include chronic wasting disease (CWD) of cervids. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is currently considered the gold standard for diagnosis of a prion infection but may be insensitive to early or sub-clinical CWD that are important to understanding CWD transmission and ecology. We assessed the potential of serial protein misfolding cyclic amplification (sPMCA) to improve detection of CWD prior to the onset of clinical signs. We analyzed tissue samples from free-ranging Rocky Mountain elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni) and used hierarchical Bayesian analysis to estimate the specificity and sensitivity of IHC and sPMCA conditional on simultaneously estimated disease states. Sensitivity estimates were higher for sPMCA (99.51%, credible interval (CI) 97.15–100%) than IHC of obex (brain stem, 76.56%, CI 57.00–91.46%) or retropharyngeal lymph node (90.06%, CI 74.13–98.70%) tissues, or both (98.99%, CI 90.01–100%). Our hierarchical Bayesian model predicts the prevalence of prion infection in this elk population to be 18.90% (CI 15.50–32.72%), compared to previous estimates of 12.90%. Our data reveal a previously unidentified sub-clinical prion-positive portion of the elk population that could represent silent carriers capable of significantly impacting CWD ecology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

CWD is a neurodegenerative disease first seen in captive Colorado cervid populations in 1967, later identified as a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) in 19781 and first found in free-ranging populations in 19811,2. Prions, the infectious agent of TSEs, arise from the misfolding of the normal host-encoded cellular prion protein (PrPC) into an insoluble, aggregated and infectious form that resists protease degradation. Prions causing CWD arise from PrPCWD, the misfolded, infectious form of cervid PrPC. CWD, the only known TSE to occur in free-ranging wildlife, affects several cervid species including elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni), mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), white-tailed deer (O. virginianus) and less commonly moose (Alces alces spp.). Prevalence of CWD in free-ranging deer populations in Colorado and Wyoming ranges from 0–30% and prevalence in free-ranging elk herds ranges from 0–13% in Colorado3,4,5,6. CWD and sheep scrapie are capable of both horizontal transmission from infected individuals7,8,9 as well as efficient indirect transmission from contaminated environments10,11,12,13.

Despite cross-species transmissibility of PrPCWD among cervids, the pathogenesis of the disease may be different between deer and elk. For example, studies with experimentally infected deer suggest that PrPCWD infect and replicate in peripheral lymphatic tissues prior to neuroinvasion14,15. Studies with captive or experimentally infected elk are less conclusive and suggest prions may first be detectable in the obex of the brain stem or the retropharyngeal lymph node without a clear pattern16,17,18. Studies of free-ranging elk, however, suggest that PrPCWD can likely be detected first in lymphatic tissue19. It is unclear if route of inoculation or prion strain can also affect these apparent differences.

Infected animals shed prions into the environment through saliva, feces, urine and even antler velvet15,20,21,22,23,24. Studies have successfully transmitted PrPCWD through a single dose of urine or feces from animals displaying signs of CWD, indicating that at the time of clinical disease sufficient prions are shed to result in an infectious dose24,25. However, at what stage(s) of disease animals shed prions into the environment remains unclear. If shedding occurs early in disease, a sub-clinical animal may not only shed prions into the environment, increasing the infectious reservoir, but may also transmit CWD horizontally to their associates. Unfortunately little is known about the prevalence of early or sub-clinical infection and what role they may play in CWD transmission ecology. This ignorance raises a critical question that must be answered: how long do free-ranging animals live once infected? Answering it requires detection of prion infections as early as possible in the course of infection.

Cervid prion protein gene (PRNP) polymorphisms can influence CWD kinetics. Elk PRNP methionine or leucine polymorphism at codon 132 can dramatically affect incubation time and possibly susceptibility of inoculated elk20,21,22,23,24,26. Experimental and observational evidence suggests that 132LL homozygous elk are rare (≤2.5%) in free-ranging populations20,25,27,28 and when inoculated have a substantially delayed disease course (>48 months) in captivity compared to MM homozygote and ML heterozygote elk (12–24 months)26,29. Despite differences in disease kinetics, Perucchini et al.27 found that the prevalence of CWD within elk genotypes was not disproportionate, indicating the three genotypes maintain proportional CWD prevalence despite the disease course differences. Whether cervid PRNP genotype affects transmission and shedding of PrPCWD remains uncertain. Surveys of free-ranging deer suggest increased rates of CWD between 2–11 years of age30 but work on elk suggests a much wider age range can be infected19 and no study to date has quantified the interaction between age and prevalence of CWD in elk.

Currently, prion protein immunohistochemistry (IHC) of brain tissue and lymph nodes is the gold standard for CWD detection31. However, this method requires 2–3 weeks for sample preparation, relatively large quantities of well-preserved tissue and specialized training for accurate microscopy work. Commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay-based tests detect prion infection more rapidly and with similar sensitivity to IHC32. Serial protein misfolding cyclic amplification (sPMCA) has emerged in the field of prion research as a reliable and sensitive alternative detection assay for a variety of tissue and sample types1,22,27,33,34,35,36,37. Haley et al.38 found comparable sensitivity between an abbreviated sPMCA vs. IHC in longitudinal tonsil biopsies from experimentally inoculated, captive white-tailed deer.

We have optimized both sensitivity and specificity to maximize PrPCWD amplification and detection, leading to a more sensitive sPMCA protocol that processes samples in less than two weeks23. We used sPMCA to test obex tissue samples from a free-ranging elk herd in the Rocky Mountain National Park (RMNP), Estes Park, CO; and Bayesian hierarchical modeling to compare our results to IHC of retropharyngeal lymph node and obex tissue and estimate prevalence of PrPCWD in this herd.

Results

Of the 85 elk tested, 20 were IHC-positive in one or more tissues (Table 1). Of the 20 IHC-positive animals, sPMCA identified 19 correlating obex samples as positive. The one sample that sPMCA did not generate a positive result for was a 2011 sample found to be IHC-positive in the RPLN only. sPMCA also identified an additional 18 IHC-negative samples as PrPCWD-positive.

We found a strong correlation between sPMCA and IHC scores for each elk sample (Figure 1). Linear regression found a positive association (slope = 0.39, R2 = 0.64) between samples scoring positive by both IHC and sPMCA. Samples that disagreed, scoring IHC negative but sPMCA positive, were not included in the linear regression, but are overlaid in Figure 1 to show the low sPMCA scores of samples that were otherwise IHC-negative. A high rate of sPMCA-positive samples in 2010 suggested an unidentified portion of those samples may have been false-positives due to contamination. This may also be the case for 2009. However, sPMCA did identify 4 additional positives in 2011 compared to the 3 found by IHC (6 total, Table 1 and Figure S1). One of the IHC-positive samples was the single disagreement mentioned above.

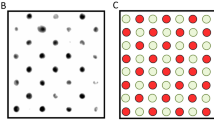

Correlation between IHC score and sPMCA score of each sample.

(a) Sample scores by IHC and sPMCA were compared by linear regression to evaluate correlation between the two tests. Samples found positive by both tests are considered in “Agreement” (black circles). Samples found negative by IHC but positive by sPMCA are considered in “Disagreement (grey triangles). Each data point represents the mean of all replicates per animal. (b) Representative IHC of a positive obex sample. Scale bars, 100 μm. (c) Representative western blots: Lane 1, undigested NBH; lanes 2–3, negative elk obex from ND and MT after 6 rounds of sPMCA. Lanes 4–5, RMNP elk obex featured in (b) after 3 and after 6 sPMCA rounds (lanes 6 & 7).

We developed a novel hierarchical Bayesian model to estimate specificity, sensitivity and disease prevalence that considers all IHC and sPMCA test results (Figure 2). The model simultaneously estimates infection status of each individual animal and all derived quantities of interest, including estimates of PrPCWD prevalence within the herd and sensitivity and specificity of IHC for each tissue and sPMCA. This model also allowed us to quantify the potential effects of contamination in two of the collection years (2009 and 2010).

The separate analysis of Trusted and Unknown samples allowed us to estimate sPMCA specificity by amplification round (Figure 3a) and for each group of samples (Figure 3b). When compared to specificity of raw data from previous sPMCA studies23,35,39 (99.60%, CI 98.00–100%) our model estimates specificity for our Trusted samples to be 93.85% (CI 90.00–96.84%) and a reduced specificity of 61.98% (CI 51.81–71.18%) for Unknown samples after six PMCA rounds.

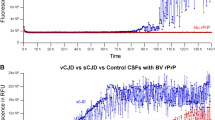

Specificity and sensitivity estimates of sPMCA and IHC.

(a) Specificity estimates of sPMCA by amplification round. Three sample groups are presented: Known samples are positive controls used in previous studies and presented as raw data; Trusted samples are those which are verified by IHC or are from the 2011 sampling; and Unknown samples are all remaining samples which may include contamination-related false positives. (b) Overall sPMCA specificity estimates for Trusted and Unknown samples. The overall specificity of sPMCA is estimated at 93.9% (CI 90.1–96.9%) for Trusted samples and 63.4% (CI 52.6–74.1%) for Unknown samples. (c) Sensitivity of sPMCA by round. Sensitivity increases with each amplification round to 94.68% (CI 83.12–99.84%) by round 6. (d) Overall sensitivity estimates for IHC and sPMCA. Sensitivity estimates for IHC by individual tissue (obex (76.56%, CI 57.00–91.46%) and RPLN (90.06%, CI 74.13–98.70%)) and combined 98.99% (CI 90.01–100%); one replicate of sPMCA after 6 rounds (94.68%, CI 83.12–99.84%); and two replicates of sPMCA (99.51%, CI 97.15–100%).

We did not separate samples into Trusted and Unknown groups for sensitivity analyses because sensitivity is the ability of the test to correctly identify a true positive. The sensitivity of sPMCA after 6 rounds was estimated at 94.68% (CI 83.12–99.84%) for one replicate. Again we compared sensitivity of known positive samples (97.00%, confidence interval 95.07–99.02%) from previous work to demonstrate the agreement between raw data and the model estimates (Figure 3C). We typically assess at least two replicate samples by PMCA, which our model predicts to increase sensitivity to 99.51% (CI 97.15–100%) with corresponding decreases in specificity of trusted (91.03%, CI 84.42–97.80%) and unknown (42.01%, CI 27.72–50.11%) samples.

We also calculated sensitivity estimates for IHC of obex and RPLN (Figure 3D). RPLN IHC (90.06%, CI 74.13–98.70%) was more sensitive than obex (76.56%, CI 57.00–91.46%). Combining obex and RPLN IHC increases sensitivity to 98.99% (CI 90.01–100%). Inputting all data from the two IHC and duplicate PMCA tests, our model estimated the overall period prevalence of CWD for 2009–2011 to be 18.90% (CI 8.71–32.39%; Figure 4).

The age distribution of elk sampled by year showed an overlap among years, with 2009 and 2010 including primarily middle-aged animals (Figure 5A). Our model predicts the primary age of infected animals lies between 2–11 years (Figure 5B). Means and credible intervals for the logistic regression coefficients, ®, are reported in Supplemental Table 2. No difference in overall prevalence was found between MM and ML elk (p = 1.0).

Age effect on prion infection prevalence.

(a) Age distribution of animals sampled by year. (b) Derived posterior probability density for prevalence (P(z = 1)) across observed ages. Black dots represent mean values and gray dots, 95% confidence intervals. Left y-axis shows prevalence within age groups demonstrating the predominant age of infected animals lies between 2 and 10 years as previously documented. The right y-axis and the histogram in the background show the observed frequency of ages of elk sampled in this study.

Discussion

We compared specificity and sensitivity estimates of two tests for CWD prions in a free-ranging elk herd in RMNP, the gold standard PrPCWD IHC versus sPMCA testing analyzed by Bayesian hierarchical modeling. We found that sPMCA detected PrPCWD in the obex of infected elk with greater sensitivity than IHC of obex or RPLN. We used these estimates to predict prevalence of prion infection in this herd and discovered animals with subclinical CWD may represent a significant carrier state in this population. Although there appears to be no upper age limit to infection in adult female elk19, we found that prevalence decreases with age and the primary age cohort for infection is 2 to 11 years.

sPMCA specificity was lower than expected, likely due to cross-contamination during necropsy in early years, which was reflected in the difference in sPMCA-positive results between 2010 and 2011. Our decontamination protocol instituted during necropsy in 2011 to limit cross-contamination reduced the sPMCA-positive rate to twice the IHC rate (sPMCA = 18.2% and IHC = 9.1%, Table 1). Our cross-contamination mitigation strategy provided us with a year of samples that we considered contamination-free.

We therefore consider the data showing the identification of 4 additional positive samples by sPMCA in 2011 to be reliable and used them to inform our model of sPMCA specificity and sensitivity compared to IHC. Detection of four unique positives by sPMCA correlates with the low amounts of PrPCWD predicted to exist in animals with early and sub-clinical disease.

Hierarchical Bayesian modeling allowed us to work with authentic but possibly imperfect data and let the model test parameters to find the best estimates. Having to discount some of the sPMCA findings for 2009 and 2010 was not ideal, but the model allowed us to adapt to the realities of research. When we removed possible false-positive results for specificity estimates the model estimated that specificity increased from 61.98% (Unknown samples) to 93.9% (Trusted samples). Uncertainty introduced by possible sample contamination likely resulted in the model predicting a lower specificity in these field samples than our previous specificity of 99.6% observed in controlled laboratory experiments35. Increased specificity using Trusted while excluding Unknown samples shows that sPMCA has a high specificity when cross-contamination is prevented. Moreover, if replicate samples are used, sensitivity increases to 99. 51%, while specificity remains acceptable at 91.03%. We consider these to be conservative estimates of sensitivity and specificity considering possible contamination at early collections and our model allows us to use imperfect data to inform our model and estimate prevalence in this herd.

Our results suggest that prevalence of prion infection in this free-ranging RMNP elk herd is much higher than previously reported. Prior to 2013, the CWD prevalence in elk surrounding RMNP was estimated at <2%19,40,41. In 2013, Monello et al. reported CWD prevalence of 12.9% in RMNP based on PrPCWD IHC of RAMALT19,35, over 4 times higher than previous reports. Here we report an estimated overall prevalence of 18.90%, consistent with the finding by Monello et al., who found 28% of adult female elk were infected during the course of their three-year study. We conclude that sPMCA can detect early cases of PrPCWD infection and our model conservatively estimated overall prevalence since all known PrPCWD positive animals from 2008, which tested positive on RAMALT biopsy, were removed from the sample population.

The higher overall prevalence estimate in this herd suggests previous measurements have been missing a large portion of PrPCWD -positive animals and that a long history of exposure to prions and decades of relatively high densities on the winter range may have led to increased prevalence19,42,43. Further study is required to identify possible ecological differences in this herd compared to neighboring ones.

As an amplifying assay, sPMCA has previously been shown to be extremely specific and sensitive in prion detection studies19,22,40,44,45 but had not been directly compared to IHC in elk or in samples from free-ranging animals. This study has shown that sPMCA on the obex alone is more sensitive than IHC on obex or RPLN. sPMCA also detected several positive obex samples, which were IHC-negative from 2011. We argue that this increased detection represents early stage infections or sub-clinical animals, which may or may not shed PrPCWD or develop clinical disease at a later time point.

Similar to Monello et al.19, our sensitivity analysis of IHC by tissue indicates that in this study population, that IHC in the RPLN was actually more effective in detecting positives animals than the obex. These results indicate that IHC on the obex might not be the best method to detect nascent PrPCWD in elk and perhaps the premise that the infection course is different between deer and elk is not absolute. Determining whether sPMCA in the RPLN would show a similar improvement on sensitivity compared to obex requires further study.

Our data demonstrate that previous IHC-based studies are possibly missing early stage or sub-clinical cases in sampled populations. It is widely accepted that IHC is sensitive enough to detect pre-clinical cases, but we propose that sPMCA can detect additional cases even earlier, possibly soon after infection. In previous work we found sPMCA had a detection limit of 10−9 35,46 which is much more sensitive than the sensitivity of a mouse bioassay at 10−4. This suggests that animals found positive by sPMCA have much lower levels of PrPCWD than animals with clinical disease, but are indeed infected. The detection of very early sub-clinical cases raises the question of biological relevance at the population level. We propose that this sub-clinical subset of the population may be ecologically important to the disease transmission cycle because of potential preclinical vertical transmission from mother to offspring47, horizontal transmission through direct contact, or indirect transmission through environmental deposits of prions.

It remains unclear when animals begin shedding prions into the environment. Through the use of a mouse bioassay Tamguney et al.22,24,44,45 showed asymptomatic deer were capable of shedding infectious levels of CWD as early as 10 months prior to clinical disease. Bioassays, both in mice and deer, have limited sensitivity so shedding could be occurring much earlier than 10 months post-infection but at levels insufficient to cause clinical disease in the infected host. It is also unclear if genotype plays a role in prion shedding, as well as disease course. Our data suggest that having at least one L allele at codon 132 does not alter the disease prevalence within the ML genotype, supporting data reported by Perucchini et al.27. The slow disease course and the potential existence of a carrier state facilitate a high prevalence and frequent opportunity for transmission between animals with the MM and ML genotypes.

It is commonly stated in the literature that CWD is an invariably fatal disease, but it may be more accurate to state that once animals begin to show clinical signs they are certain to succumb to CWD or other associated causes of death such as predation4,24,48. Perhaps other carrier states exist within the population, which may or may not contribute to the transmission and deposition of prions in the population and the environment. Further research is required to address the role of a carrier state in the ecology of CWD transmission.

The application of sPMCA will be important both to research and for diagnostic investigation and may improve state and federal surveillance programs for CWD in both naïve and endemic host populations. Increased sensitivity and the need for only obex tissue, may lead to detection of new focal points prior to clinical disease emerging in otherwise CWD-free populations. Additionally, in the economically and politically difficult scenario of culling captive herds that tested positive for CWD, extremely sensitive assays such as sPMCA of prions from tissue and excreta are essential to verify that more animals besides the index case were infected and if any sub-clinical carriers may have been shedding into the environment.

Overall, our data contribute to the increasing evidence that a portion of a herd may be infected, but die from other causes while infected with PrPCWD because of age, genetic susceptibility or other unknown factors. However, the contribution of prions shed into the environment from this sub-clinical population may be important and requires further investigation. The existence of an infectious PrPCWD carrier state aligns with disease ecology theory, which proposes balance between transmissibility and pathogenesis of a pathogen. As such, through selection pressures from the host and external environment the pathogen will tend towards the greatest transmissibility strategy. CWD transmission may be more complicated than disease ecology might predict, since prolonged persistence and indirect transmission of prions in the environment may potentiate spread without affecting pathogenesis.

Despite the fact that prions are only protein, studies continue to point at evolutionary behavior and selection pressures of prions which indicate that like other pathogens, prions are capable of evolving and adapting to their environment4,27,48,49. With increasing prevalence at the population level, as is reported in this study, sPMCA will continue to be an important tool to investigate CWD in wildlife.

Methods

Mice

All mice were bred and maintained at Lab Animal Resources, accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Lab Animal Care International, in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Colorado State University.

Elk brain tissue samples

Brain tissues were collected at necropsy from 85 free-ranging elk that were radio collared and later euthanized for research and management purposes19. Briefly, 136 elk were initially captured, sampled and collared in 2008. Rectoanal mucosal-associated lymphatic tissue (RAMALT) samples were collected from each elk during initial capture and tested for PrPCWD by IHC7,8,9,38,50. In 2008, samples were collected from 11 PrPCWD -positive animals that were recaptured, euthanized and necropsied within two months of original capture. In subsequent years 17, 24 and 33 randomly selected animals were recaptured, euthanized, necropsied and included in this study. These opportunistic collections were IHC-negative via RAMALT biopsy in 2008 and no elk exhibited clinical evidence of CWD when euthanized. Elk were euthanized in the field then transported to the TSE necropsy facility at the Colorado State University Veterinary Teaching Hospital within 8 hours of euthanasia19. We removed a primary incisor from all elk carcasses to determine age by cementum analysis (Matson Lab, Milltown, MT). Field euthanasia and subsequent necropsies were approved by NPS (permit ROMO-2007-SCI-0077), Colorado Division of Wildlife (permit TR1081) and CSU IACUC (permit 07-231A).

Multiple tissues were collected from each animal during necropsy. Here we compare IHC results from obex and retropharyngeal lymph nodes14,15,50,51 to sPMCA results from the obex alone. All lymph node samples and half the obex sample were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for IHC analaysis; the other half of the obex sample was stored in a whirl pack at −80°C for testing by sPMCA.

IHC

Sections of retropharyngeal lymph node (RPLN) and obex were examined by IHC as previously described16,50. Briefly for IHC, tissues were fixed, paraffin-embedded and 10 μm sections cut, mounted on glass microscope slides and immunolabeled with anti-prion protein monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) F99/97.6.1 (mAb 99) and mAb P4. PrPCWD was visualized by incubation with alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated donkey antibodies against mouse IgG and fast red chromogen that revealed red aggregate deposits in neural and lymphoid tissues. A scoring system (0–10) was used to evaluate intensity of PrPCWD deposition as described in Spraker et al.52.

Brain Homogenization

Frozen elk obex samples were partially thawed and approximately 200 mg of tissue was collected from the interior of the obex sample, placed into a 2 ml tube containing silica beads and 180 μl of sPMCA buffer #1 (150 mM NaCl, 4 mM EDTA, in PBS) was added. Tissues were homogenized using a FastPrep machine (Thermo Scientific) as outlined in Meyerett et al.46. The clarified 10% homogenate supernatant was removed and stored at −80°C.

sPMCA substrate consisted of 10% mouse normal brain homogenate (NBH) prepared in a prion-free room from Tg5037 mice expressing cervid PrPC as previously described46.

sPMCA and western blotting

Twenty-five μl of RMNP elk obex homogenate was added to 25 μl NBH in 0.2 ml tubes. Samples were sonicated in a Misonix 4000 sonicator (Misonix Inc., Farmingdale, NY) for 40 s every 30 minutes for 24 hours at 37°C constituting one round46. For each subsequent round, 25 μl of each sample from the previous round was combined with 25 μl of fresh NBH. Duplicate samples were run for 6 sPMCA rounds to balance desired sensitivity and specificity (>90%) as previously observed35. Each sPMCA experiment contained at least six NBH-negative controls and two positive plate controls (CWD-positive elk brain homogenate E2, 1:1000). The negative brain samples were collected from Montana (n = 1) and North Dakota (n = 10) and homogenized as previously described23 Montana eNBH was confirmed negative by bioassay in CWD susceptible mice (data not shown) and ND samples were confirmed negative by ELISA (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Elk samples collected in 2008 and 2009 were not blind to laboratory researchers, but all 2010 and 2011 samples were blinded. The PrPCWD status of all negative controls was known at the time of sPMCA.

PMCA samples were assayed by western blot as previously described23,46. Briefly, 18 μl of sample was digested with 2 μl of 50 μg/ml proteinase K (PK, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) for 30 minutes at 45°C. Samples were electrophoresed, electro-transferred to PVDF membranes and visualized with HRP-conjugated anti-PrP Bar-224 monoclonal antibody (SPI-Bio, Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France). Because prion load inversely correlates with the round in which it is first detected, samples were given a score inversely proportional to the first positive sPMCA round23. For example, if a sample scored positive in the first of six rounds, it received a sample score of 6. A positive sample detected in round six would receive a score of 1 and a negative sample would be scored 0.

Cross-contamination management

During the first three years of necropsies (2008–2010), decontamination was not standard practice during tissue collection. Necropsies from 2009–2011 were performed in a new TSE necropsy room, reducing the risk of contamination. In 2011, a decontamination protocol was implemented to further prevent cross-contamination during sample collection, including sodium dodecyl sulfate/acetic acid46,53 treatment of working surfaces and all necropsy instruments and glove and apron changes between animals. Disposable sterile scalpels were used for all CNS tissue harvest. Samples were processed according to protocols implemented to prevent cross-contamination at the lab bench, including using sterile scalpels, forceps and clean gloves during sub-sampling, homogenization and sPMCA.

Model to estimate specificity, sensitivity and prevalence

The model is represented as a network diagram in Figure 2. Each animal was considered to have a true infection status, denoted zi, where zi = 0 when animal i is uninfected and zi = 1 when infected. Infection status was modeled as a logistic regression with age and age covariates2, as well as a categorical covariate for the samples from the year 2008, such that:

For example, the IHC results for the obex tissue were described by a mixture model as follows:

We denote sPMCA results for individual i and replicate j across amplification rounds t = 1:6 as wi,j,t which is contingent upon the latent disease state of individual i, Sensitivity and Specificity probabilities across amplification rounds, Se and Sp and the result from the previous round where applicable, wi,j,t-1.

Se and Sp represent the probability of a sPMCA test result transitioning from a negative test result to a positive within amplification round t. These parameters are modeled as flat Dirichlet distributions of length T + 1. Incorporating the probability of a negative test result allows the probabilities to sum to one. This transition model is a modification of the Cormack-Jolly-Seber survival model with perfect detection54. The parallel occurs because after a sample is positive in one sPMCA cycle, it remains positive in the following rounds, just as, for example, a mortality event at any time guarantees all following times maintain that state. The model was fit to the data in JAGS 3.1.055,56 with the rjags package55 in the R 2.15.1 computing environment57.

Errors in specificity, or false positives, can occur as a result of cross-contamination of samples during necropsy or possibly by spontaneous misfolding during sPMCA. We previously reported our method of sPMCA has a specificity of 99.6% in the laboratory setting35. Negative samples used for this sPMCA experiment were used to show specificity in our laboratory setting, but do not account for possible necropsy contamination of the elk tissues. To remove bias from possible necropsy-related false positives in years 2009 and 2010 we separated “Trusted” from “Unknown” samples. Trusted samples were those found positive by IHC (2008–2010) and all samples from 2011, when we employed decontamination techniques at necropsy. Unknown samples are IHC-negative samples from 2009 and 2010. sPMCA results for these samples could be true, sub-clinical positives outside of the detection limit of IHC, or they could be false positives resulting from contamination during sample collection at necropsy. To maintain a conservative estimate of the specificity of sPMCA, Trusted and Unknown samples were assumed to have independent specificity probabilities.

Errors in sensitivity, or false negatives, for either assay occurred for two reasons: either the concentration of PrPCWD was below the detection limit of the assay or, despite the overall presence of PrPCWD in the tissue, the exacted portion that was assayed did not contain detectable levels of PrPCWD due to non-homogenous distribution19,30,41,58. All estimates are reported with a 95% Bayesian credible interval (CI).

Genetic data for 30 MM and 30 ML randomly selected animals were used to assess for prevalence differences between genotypes. IHC and sPMCA results were pooled allowing for positive or negative status to be tested against MM and ML genotype status using a Fisher's Exact Test (p < 0.05).

References

Williams, E. S. & Young, S. Chronic wasting disease of captive mule deer: a spongiform encephalopathy. J. Wild. Dis. 16, 89–98 (1980).

Williams, E. S. & Young, S. Spongiform encephalopathy of Rocky Mountain elk. J. Will. Dis. 18, 465–471 (1982).

Walter, W. D., Walsh, D. P., Farnsworth, M. L., Winkelman, D. L. & Miller, M. W. Soil clay content underlies prion infection odds. Nat. Comm. 2, 200–6 (2011).

Miller, M. W. et al. Lions and prions and deer demise. PLoS ONE 3, e4019 (2008).

Edmunds, D. R. Chronic wasting disease ecology and epidemiology of white-tailed deer in Wyoming. A Dissertation. 1–224 (2013). at <http://search.proquest.com/docview/304452515> (Date of access: 06/02/2015).

Colorado Parks and Wildlife. CWD in Colorado: 2010–2011 Surveillance Update. 1–1 (2011). at <https://cpw.state.co.us/Documents/Research/Mammals/Publications/2010-2011WILDLIFERESEARCHREPORT.pdf> (Date of access: 06/02/2015).

Dickinson, A. G., Stamp, J. T. & Renwick, C. C. Maternal and lateral transmission of scrapie in sheep. J. Comp. Path. 84, 19–25 (1974).

Miller, M. W. & Williams, E. S. Prion disease: horizontal prion transmission in mule deer. Nature 425, 35–36 (2003).

LJ, H. A review of the epidemiology of scrapie in sheep. Rev. Sci. Tech. 15, 827–852 (1996).

Miller, M. W., Williams, E. S., Hobbs, N. T. & Wolfe, L. L. Environmental sources of prion transmission in mule deer. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10, 1003–1006 (2004).

Mathiason, C. K. et al. Infectious Prions in Pre-Clinical Deer and Transmission of Chronic Wasting Disease Solely by Environmental Exposure. PLoS ONE 4, e5916 (2009).

Georgsson, G., Sigurdarson, S. & Brown, P. Infectious agent of sheep scrapie may persist in the environment for at least 16 years. J. Gen. Virol 87, 3737–3740 (2006).

Dexter, G. et al. The evaluation of exposure risks for natural transmission of scrapie within an infected flock. BMC Vet. Res. 5, 38 (2009).

Nichols, T. A. et al. Intranasal Inoculation of White-Tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) with Lyophilized Chronic Wasting Disease Prion Particulate Complexed to Montmorillonite Clay. PLoS ONE 8, e62455 (2013).

Fox, K. A., Jewell, J. E., Williams, E. S. & Miller, M. W. Patterns of PrPCWD accumulation during the course of chronic wasting disease infection in orally inoculated mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus). J. Gen. Virol. 87, 3451–3461 (2006).

Spraker, T. R., Balachandran, A., Zhuang, D. & O'Rourke, K. I. Variable patterns of distribution of PrP(CWD) in the obex and cranial lymphoid tissues of Rocky Mountain elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni) with subclinical chronic wasting disease. Vet. Rec. 155, 295–302 (2004).

Race, B. L. et al. Levels of abnormal prion protein in deer and elk with chronic wasting disease. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13, 824–830 (2007).

Peters, J., Miller, J. M., Jenny, A. L., Peterson, T. L. & Carmichael, K. P. Immunohistochemical diagnosis of chronic wasting disease in preclinically affected elk from a captive herd. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 12, 579–82 (2000).

Monello, R. J. et al. Efficacy of antemortem rectal biopsies to diagnose and estimate prevalence of chronic wasting disease in free-ranging cow elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni). J. Wild. Dis. 49, 270–278 (2013).

Haley, N. J., Mathiason, C. K., Zabel, M. D., Telling, G. C. & Hoover, E. A. Detection of sub-clinical CWD infection in conventional test-negative deer long after oral exposure to urine and feces from CWD + deer. PLoS ONE 4, e7990 (2009).

Henderson, D. M. et al. Rapid Antemortem Detection of CWD Prions in Deer Saliva. PLoS ONE 8, e74377 (2013).

Angers, R. C. et al. Chronic Wasting Disease Prions in Elk Antler Velvet. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15, 696–703 (2009).

Pulford, B. et al. Detection of PrPCWD in feces from naturally-exposed Rocky Mountain elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni) using protein misfolding cyclic amplification. J. Wild. Dis. 48, 424–435 (2012).

Tamgüney, G. et al. Asymptomatic deer excrete infectious prions in faeces. Nature 461, 529–32; 10.1038/nature08289 (2009).

Haley, N. J., Seelig, D. M., Zabel, M. D., Telling, G. C. & Hoover, E. A. Detection of CWD prions in urine and saliva of deer by transgenic mouse bioassay. PLoS ONE 4, e4848 (2009).

Hamir, A. N. et al. Preliminary observations of genetic susceptibility of elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni) to chronic wasting disease by experimental oral inoculation. J Vet Diagn Invest. 18, 110–114 (2006).

Perucchini, M., Griffin, K., Miller, M. W. & Goldmann, W. PrP genotypes of free-ranging wapiti (Cervus elaphus nelsoni) with chronic wasting disease. J. Gen. Virol. 89, 1324–1328 (2008).

O'Rourke, K. I. et al. PrP genotypes of captive and free-ranging Rocky Mountain elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni) with chronic wasting disease. J. Gen. Virol. 80, 2765–2769 (1999).

O'Rourke, K. I. et al. Elk with a long incubation prion disease phenotype have a unique PrPd profile. Neuroreport 18, 1935–1938 (2007).

Miller, M. W. et al. Epizootiology of chronic wasting disease in free-ranging cervids in Colorado and Wyoming. J. Wildl. Dis. 36, 676–90 (2000).

USDA Animal Health Inspection Service. Animal Health: Chronic Wasting Disease Information. at <http://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/animal_diseases/cwd/diagnostics.shtml> (Date of access: 05/09/2014).

Hibler, C. P. et al. Field validation and assessment of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detecting chronic wasting disease in mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and Rocky Mountain elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni). J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 15, 311–319 (2003).

Saborio, G., Permanne, B. & Soto, C. Sensitive detection of pathological prion protein by cyclic amplification of protein misfolding. Nature 411, 810–3 (2001).

Saunders, S. E., Shikiya, R. A., Langenfeld, K., Bartelt-Hunt, S. L. & Bartz, J. C. Replication efficiency of soil-bound prions varies with soil type. J. Virol. 85, 5476–5482 (2011).

Nichols, T. A. et al. Detection of protease-resistant cervid prion protein in water from a CWD-endemic area. Prion 3, 171–183 (2009).

Soto, C. et al. Pre-symptomatic detection of prions by cyclic amplification of protein misfolding. FEBS Letters 579, 638–642 (2005).

Saa, P., Castilla, J. & Soto, C. Ultra-efficient Replication of Infectious Prions by Automated Protein Misfolding Cyclic Amplification. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 35245–35252 (2006).

Haley, N. J. et al. Sensitivity of protein misfolding cyclic amplification versus immunohistochemistry in ante-mortem detection of chronic wasting disease. J. of Gen. Virol. 93, 1141–1150 (2012).

Michel, B. et al. Genetic Depletion of Complement Receptors CD21/35 Prevents Terminal Prion Disease in a Mouse Model of Chronic Wasting Disease. J. Immunol. 189, 4520–7 (2012).

Colorado Parks and Wildlife. Report: Chronic wasting disease in Colorado, 2006–2008. 1–5 (2009). at <http://cospl.coalliance.org/fedora/repository/co:9702/nr62w292009internet.pdf> (Date of access: 05/09/2014).

Thomsen, B. V. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of rectal mucosa biopsy testing for chronic wasting disease within white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) herds in North America: effects of age, sex, polymorphism at PRNP codon 96 and disease progression. J Vet. Diag. Invest. 24, 878–887 (2012).

Lubow, B. C., Singer, F. J., Johnson, T. L. & Bowden, D. C. Dynamics of Interacting Elk Populations within and Adjacent to Rocky Mountain National Park. J. Wild. Manag. 66, 757 (2002).

Monello, R. J., Powers, J. G. & Hobbs, N. T. Survival and population growth of a free-ranging elk population with a long history of exposure to chronic wasting disease. J. Wild. Manag. 78, 214–223 (2014).

Wyckoff, A. C. et al. Estimating Prion Adsorption Capacity of Soil by BioAssay of Subtracted Infectivity from Complex Solutions (BASICS). PLoS ONE 8, e58630 (2013)

Nichols, T. A. et al. Detection of prion protein in the cerebrospinal fluid of elk (Cervus canadensis nelsoni) with chronic wasting disease using protein misfolding cyclic amplification. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 24, 746–749; 10.1177/1040638712448060 (2012).

Meyerett, C. et al. In vitro strain adaptation of CWD prions by serial protein misfolding cyclic amplification. Virology 382, 267–76; 10.1016/j.virol.2008.09.023.

Nalls, A. V. et al. Mother to offspring transmission of chronic wasting disease in reeves' muntjac deer. PLoS ONE 8, e71844 (2013).

Krumm, C. E., Conner, M. M., Hobbs, N. T., Hunter, D. O. & Miller, M. W. Mountain lions prey selectively on prion-infected mule deer. Biol Lett 6, 209–211 (2009).

Li, J., Browning, S., Mahal, S. P., Oelschlegel, A. M. & Weissmann, C. Darwinian Evolution of Prions in Cell Culture. Science 327, 869–872 (2010).

Spraker, T. R. et al. Antemortem detection of PrPCWD in preclinical, ranch-raised Rocky Mountain elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni) by biopsy of the rectal mucosa. J. Vet. Diagn Invest. 21, 15–24 (2009).

Williams, E. S. & Young, S. Neuropathology of chronic wasting disease of mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) and elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni). Vet. Pathol. 30, 36–45 (1993).

Spraker, T. R. et al. Detection of the abnormal isoform of the prion protein associated with chronic wasting disease in the optic pathways of the brain and retina of Rocky Mountain elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni). Vet. Pathol. 47, 536–546 (2010).

Peretz, D. et al. Inactivation of prions by acidic sodium dodecyl sulfate. J. Virol. 80, 322–331 (2006).

Lebreton, J.-D., Burnham, K. P., Clobert, J. & Anderson, D. R. Modeling Survival and Testing Biological Hypotheses Using Marked Animals: A Unified Approach with Case Studies. Ecol.l Monog. 62, 67–118 (1992).

Plummer, M. JAGS: A program for analysis of Bayesian graphical models using Gibbs sampling. URL http://citeseer.ist.psu.edu/plummer03jags.html (2003). at <http://www.ci.tuwien.ac.at/Conferences/DSC-2003/Drafts/Plummer.pdf> (Date of access: 05/09/2014).

Plummer, M. JAGS version 3.0.0 user manual. sourceforge.net (2011). Accessed at at <http://sourceforge.net/projects/mcmc-jags/files/> (Date of access: 05/09/2014).

R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: the R Foundation for Statistical Computing. ISBN: 3-900051-07-0. Accessed at http://www.R-project.org/. (Date of access: 11/24/2014)

Spraker, T. R. et al. Spongiform encephalopathy in free-ranging mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and Rocky Mountain elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni) in northcentral Colorado. J. Wild. Dis. 33, 1–6 (1997).

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Park Service for access to samples and IHC result, Dr. M. Hooten for his assistance with model design, the National Wildlife Research Center-United States Department of Agriculture and the National Science Foundation (grant EF-0914489) for funding and support of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.C.W. and M.Z. conceived the research. A.C.W., C.M., J.P., T.S., R.M., M.W. and B.P. assisted in procurement, collection and tissue preparation. A.C.W. conducted all PMCA experiments. T.S. conducted all histopathology. N.G. led and A.C.W. and M.Z. assisted in, development and execution of Bayesian model and analysis. All authors discussed the study design, results and interpretation of study. M.W., M.A., K.V. and M.Z. supervised project. A.C.W., N.G. and M.Z. wrote the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wyckoff, A., Galloway, N., Meyerett-Reid, C. et al. Prion Amplification and Hierarchical Bayesian Modeling Refine Detection of Prion Infection. Sci Rep 5, 8358 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08358

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08358

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.