Abstract

Estimating the immunocompetence of herbivore insects under elevated CO2 is an important step in understanding the effects of elevated CO2 on crop-herbivore-natural enemy interactions. Current study determined the effect of elevated CO2 on the immune response of Helicoverpa armigera against its parasitoid Microplitis mediator. H. armigera were reared in growth chambers with ambient or elevated CO2 and fed wheat grown in the concentration of CO2 corresponding to their treatment levels. Our results showed that elevated CO2 decreases the nutritional quality of wheat and reduces the total hemocyte counts and impairs the capacity of hemocyte spreading of hemolymph of cotton bollworm larvae, fed wheat grown in the elevated CO2, against its parasitoid; however, this effect was insufficient to change the development and parasitism traits of M. mediator. Our results suggested that lower plant nutritional quality under elevated CO2 could decrease the immune response of herbivorous insects against their parasitoid natural enemies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global atmospheric concentration of CO2 has increased from a pre-industrial value of 280 ppm to 396 ppm in 2013 (Mauna Loa Observatory: NOAA-ESRL) and are anticipated to double by the end of the 21st century1. Elevated atmospheric CO2 increases the photosynthetic rate, stimulating increases in biomass, yield, water content and carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (C: N) in most C3 plants2,3. Decreased foliar Nitrogen (N) and protein concentrations under elevated CO2 reduce plant nutritional quality, diminishing the value of the foliage as a resource for insect herbivores4,5. Most previous studies indicated that decreases in plant nutritional quality under elevated CO2 result in increased development times, mortality and always associated with reduced food conversion efficiency, adult weight and population fitness of herbivore insects6,7,8.

Decreased plant nutritional quality may affect the relationship between insects and their natural enemies or entomopathogens. Most previous reports have stated that plants decrease the protein concentration of their foliage in response to atmospheric CO2 enrichment3,7,9. Nevertheless, protein composition and content of plants tend to affect the immunocompetence of herbivorous insects in response to biotic stress10,11,12,13,14,15. An increase in the proportion of protein in the diet of herbivorous insect larvae leads to an increase in their protein levels and improved immune defense in their hemolymph, such as melanization, phenoloxidase (PO) activity and antibacterial activity12,13,16. However, the role of host plant nutrition in insect immunocompetence, which may alter the emergence of herbivorous insects, in the presence of their natural enemies under elevated CO2 remains almost unexplored and requires further investigation.

Hemocytes play crucial roles in the immune response of insects against their parasites17,18. Parasitoid eggs or larvae must avoid the immune responses of hemocyte to develop in the host larvae and many species perform this by decreasing the total hemocyte count (THC), inhibiting hemocyte spreading and melanization of the host haemolymph19,20. Additionally, Klemola et al. (2007)10 determined the strength of the immune response of autumnal moths, Epirrita autumnata (Borkhausen), by measuring their encapsulation rate to exposure to a foreign antigen and the PO activity of the pupal haemolymph. However, previous studies provided contradictory results, mainly due to the differences in methodology such as measuring a single-immune parameter rather than considering more immune parameters of the insect.

In this study, we investigated the immune response of H. armigera larvae to parasitization by M. mediator (Haliday) (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) under ambient and elevated CO2. We searched for potential variations in cellular and humoral immunocompetence in the hemolymph of cotton bollworm larvae during their development across different diets with altered nutritional quality. The solitary endoparasite, M. mediator, plays a key role in the natural control of cotton bollworm, which is a major agricultural pest worldwide21,22. The bottom-up effect of plant quality on host-parasitoid immune responses was then evaluated using measures of cellular and humoral effectors. The main aims of the study were as follows: 1) to determine the immunocompetence of cotton bollworm larvae reared on wheat grown under elevated CO2 and 2) to better understand how altered plant nutritional quality and parasitization affect the immunocompetence of cotton bollworm larvae under elevated CO2.

Results

Wheat ear quality

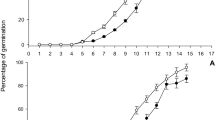

Elevated CO2 reduces the nutritional quality of wheat grains, as a result of significant decreases in nitrogen (N) Content (F1, 8 = 6.283, P = 0.037), protein (F1, 8 = 9.207, P = 0.016) and total amino acids (F1, 8 = 8.368, P = 0.020) were found in wheat grains grown under elevated CO2. However, total non-structural carbohydrate (TNC) (F1, 6 = 13.95, P = 0.010) and TNC: N (F1, 6 = 20.88, P = 0.004) were increased (Fig. 1).

The chemical composition of wheat grains grown under ambient CO2 (375 μl/L, open bars) and elevated CO2 (750 μl/L, closed bars).

(a) Nitrogen content (mg g−1), (b) Protein content (mg ml−1), (c) Total non-structural carbohydrates (TNC) (mg g−1), (d) The ratio of TNC: Nitrogen (%), (e) Total amino acid content (μmol ml−1) and (f) The proportion of water in the wheat grain (%). Each value represents the mean (±SE). * indicates statistically significant differences (LSD test, P < 0.05), ** indicates statistically significant differences (LSD test, P < 0.001) and n.s. indicates no statistically significant difference.

Protein content of cotton bollworm larvae hemolymph

Elevated CO2 significantly increased the protein content of parasitized larvae hemolymph after 72 h (F1, 8 = 16.38, P = 0.004), but decreased protein content of unparasitized larvae after 96 h (F1, 8 = 8.251, P = 0.021). Parasitism significantly decreased the protein content of hemopymph in H. armigera larvae after 72 h (F1, 8 = 13.57, P = 0.006) and 96 h (F1, 8 = 12.60, P = 0.008) under ambient CO2 (Fig. 2). Sampling time significantly affected the protein content of hemopymph in H. armigera larvae (F3, 64 = 7.539, P < 0.001) (Table 1). Significant decreases were observed in the protein content of parasitized larvae hemolymph after 72 h and 96 h under ambient (F3, 16 = 8.742, P = 0.001) and elevated CO2 (F3, 16 = 3.476, P = 0.041), compared with 24 h and 48 h (Fig. 2).

Protein content of cotton bollworm larvae (both parasitized and unparasitized) fed with wheat grain grown under ambient and elevated CO2 with M. mediator (sampled at 24, 48, 72 and 96 h post parasitization).

A: ambient CO2 without parasitism; E: elevated CO2 without parasitism; A + P: ambient CO2 with parasitism; E + P: elevated CO2 with parasitism. Each value represents the mean (±SE) of 5 replicates; Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the combinations of parasitism treatment and CO2 concentrations within the same sample time. Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences among the different sample time within the same parasitism and CO2 treatment as determined by LSD test at P < 0.05).

Total hemocyte counts of cotton bollworm larvae hemolymph

Elevated CO2 significantly decreased the THC of parasitized insects after 72 and 96 h (F1, 22 = 5.116, P = 0.034 and F1, 22 = 9.934, P = 0.005, respectively). Meanwhile, parasitism decreased the THC under elevated CO2 after 24, 72 and 96 h (F1, 22 = 11.51, P = 0.003; F1, 22 = 17.89, P < 0.001 and F1, 22 = 20.76, P < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 2A). Regardless of parasitism, more THC was calculated after 24 h under elevated CO2 (F1, 22 = 8.37, P = 0.009) (Fig. 3A). Sampling time significantly affected the THC of hemopymph in H. armigera larvae (F3, 176 = 21.17, P < 0.001) (Table 1).Significant decreases were observed in the THC of parasitized and unparasitized larvae hemolymph after 96 h under ambient and elevated CO2, compared with 24 h, 48 h and 72 h (Fig. 3A).

Cellular immunity of cotton bollworm larvae fed with wheat grain grown under ambient and elevated CO2 with M. mediator.

(a)Total hemocyte counts (×106 ml−1), (b) hemocyte spreading ratio (%) and (c) encapsulation ratio (%) of H. armigera larvae (sampled at 24, 48, 72 and 96 h post parasitization). A: ambient CO2 without parasitism; E: elevated CO2 without parasitism; A + P: ambient CO2 with parasitism; E + P: elevated CO2 with parasitism. Each value of total hemocyte counts and hemocyte spreading ratio represents the mean (±SE) of 12 replicates; each value of encapsulation ratio represents the mean (±SE) of 6 replicates; Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the combinations of parasitism treatment and CO2 concentrations within the same sample time. Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences among the different sample time within the same parasitism and CO2 treatment as determined by LSD test at P < 0.05).

Hemocyte spreading ratio of cotton bollworm larvae hemolymph

Elevated CO2 significantly decreased the hemocyte spreading ratios of parasitized insects after 72 and 96 h (F1, 22 = 8.855, P = 0.007 and F1, 22 = 11.19, P = 0.003, respectively) (Fig. 3B). Meanwhile, parasitism significantly decreased the hemocyte spreading ratios during all measured time intervals under elevated CO2 (24 h: F1, 22 = 23.20, P < 0.001; 48 h: F1, 22 = 28.51, P < 0.001; 72 h: F1, 22 = 7.593, P = 0.012 and 96 h: F1, 22 = 18.18, P < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 3B). Regardless of parasitism, elevated CO2 enhanced the hemocyte spreading ratio after 48 h (F1, 22 = 5.205, P = 0.033). Sampling time significantly affected the hemocyte spreading ratios of hemopymph in H. armigera larvae (F3, 176 = 16.93, P < 0.001) (Table 1). Significantly higher spreading ratios were observed in the parasitized larvae hemolymph after 96 h than after 24 h and 48 h under ambient (F3, 44 = 17.07, P < 0.001) and elevated CO2 (F3, 44 = 12.96, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3B).

Encapsulation ratio of cotton bollworm larvae hemolymph

Elevated CO2 did not affect the encapsulation ratio of insects larvae (F1, 80 = 1.293, P = 0.259) (Table 1, Fig.3C). Parasitism significantly decreased the encapsulation ratio after 24 and 72 h under ambient CO2 (F1, 10 = 5.295, P = 0.044 and F1, 10 = 18.22, P = 0.002, respectively) and after 72 and 96 h under elevated CO2 (F1, 10 = 5.603, P = 0.039 and F1, 10 = 7.780, P = 0.019, respectively) (Fig. 3C). Sampling time significantly affected the encapsulation ratio of hemopymph in H. armigera larvae (F3, 80 = 21.91, P < 0.001) (Table 1).Significantly higher encapsulation ratio were observed in the parasitized and unparasitized larvae hemolymph after 96 h than after 24 h, 48 h and 72 h under ambient and elevated CO2 (Fig. 3C).

Phenoloxidase activity of cotton bollworm larvae hemolymph

Elevated CO2 did not affect the PO activity of insects larvae (F1, 64 = 2.164, P = 0.146) (Table 1, Fig. 4A). Parasitism significantly decreased PO activity during all measured time intervals under ambient CO2 (24 h: F1, 8 = 21.24, P = 0.002; 48 h: F1, 8 = 6.427, P = 0.035; 72 h: F1, 8 = 9.010, P = 0.017 and 96 h:F1, 8 = 5.910, P = 0.041, respectively) and after 48 and 72 h under elevated CO2 (F1, 8 = 12.34, P = 0.008 and F1, 8 = 5.447, P = 0.048, respectively) (Fig. 4A). Sampling time significantly affected the PO activity of hemopymph in H. armigera larvae (F3, 64 = 16.93, P < 0.001) (Table 1). Significantly higher PO activity were observed in the parasitized and unparasitized larvae hemolymph after 48 h, 72 h and 96 h than after 24 h under ambient and elevated CO2 (Fig. 4A).

Humoral immunity of cotton bollworm larvae fed with wheat grain grown under ambient and elevated CO2 levels with M. mediator.

(a) Phenoloxidase activity (A490 nm min−1 mg protein−1) and (b) Melanization ratio (%) of H. armigera larvae (sampled at 24, 48, 72 and 96 h post parasitization). A: ambient CO2 without parasitism; E: elevated CO2 without parasitism; A + P: ambient CO2 with parasitism; E + P: elevated CO2 with parasitism. Each value of PO activity represents the mean (±SE) of 5 replicates; each value of melanization ratio represents the mean (±SE) of 6 replicates; Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the combinations of parasitism treatment and CO2 concentrations within the same sample time. Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences among the different sample time within the same parasitism and CO2 treatment as determined by LSD test at P < 0.05).

Melanization ratio of cotton bollworm larvae hemolymph

Elevated CO2 did not affect the melanization ratio of insects larvae (F1, 80 = 2.501, P = 0.118) (Table 1, Fig. 4B). Parasitism significantly decreased the melanization ratio of cotton bollworm larvae hymolymph during all measured time intervals under both ambient and elevated CO2 concentration (F1, 80 = 221.7, P < 0.001) (Table 1, Fig. 4B). Sampling time did not affect the melanization ratio of hemopymph in H. armigera larvae (F3, 80 = 1.938, P = 0.130) (Table 1).

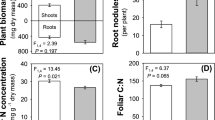

Development and parasitism traits of M. mediator

19 ± 3% and 26 ± 4% of H. armigera were parasitized by M. mediator in the ambient- and elevated-CO2 treatments, respectively. The emergency rate of parasitism, values of 72 ± 9% and 67 ± 5% were found for the ambient- and elevated-CO2 treatments, respectively. However, no significant differences related to the experimental conditions (CO2 levels) were found in the parasitism rate, emergence rate, cocoon weight, wasp weight, cocoon lifespan and wasp lifespan of M. mediator (P > 0.05, Fig. 5).

Life history parameters (means ± SE) of M. mediator parasitizing H. armigera fed with wheat grain grown under ambient and elevated CO2.

(a) Parasitism rate (%), (b) Emergence rate (%), (c) Cocoon weight (mg), (d) Female cocoon weight compared with male cocoon weight (mg), (e) Wasp weight (mg), (f) Female wasp weight compared with male wasp weight (mg). (g) Cocoon lifespan (days), (h) Wasp lifespan (days). Each value represents the mean (±SE). * indicates statistically significant differences and n.s. indicates no statistically significant difference (LSD test, P < 0.05).

Discussion

Elevated CO2 alters the chemical composition of plant tissue23. In response to atmospheric CO2 enrichment, most plants decrease the N and protein concentration of their larger foliage in order to sequester carbon, which, in turn, changes the syntheses of nutrients and secondary metabolites in the plant. N is the most important limiting resource for herbivorous insects24 and a decrease in the foliar N of host plants could limit insect growth and development, decrease the survival rates of phytophagous insects and further depress the defense capability of herbivore insects against their natural enemies25,26. European grape berry moths, Eupoecilia ambiguella, were reared on five semi-artificial diets and changes in the concentration of hemocytes and prophenoloxidase (PPO) activity were measured after a bacterial immune challenge. The result showed that the nutritional quality of diets significantly affected the immune defenses of the larvae26.

Dietary protein is an important determinant in the performance of herbivore insects. Ingested protein is digested into amino acids in the gut and finally absorbed into the hemolymph of herbivorous insects27. Constitutive immune functions rely on the insect hemocyte and rapidly activated enzyme cascades such as PO activity28,29. The baseline of these immune effectors could be impaired when limited to protein-deficient food sources13. Hence, herbivore insects reared on host plants differing in nutritional value are expected to differ in their baseline levels of constitutive defense26. Here, in the absence of parasitism, decreased hemolymph protein concentration was detected in cotton bollworm after 96 h under elevated CO2, presumably due to the long-term feeding on a reduced protein diet. Contrarily, increased hemolymph protein concentration was detected in parasitized cotton bollworms under elevated CO2, most likely due to increased intake of protein by the caterpillars to compensate for the protein cost of resistance against their parasites12. Hemolymph protein concentration has been assessed as an indication of insect condition30. Altered hemolymph protein contents of herbivorous insects that were fed on plants grown under elevated CO2 concentrations indicate that decreased protein concentrations in plants via “bottom-up” could have negative effects on herbivorous insects that have not been parasitized and could have positive effects at a higher level after parasitism by their natural enemies. Consistent with some previous studies, long-term feeding on plants with lower protein concentration generates hypotrophic insect herbivores; however, the diet eaten after challenge by natural enemies can alter the likelihood of host development and the possible capacity of an insect to influence this likelihood by altering its diet to take in more protein12,16. All of changes mentioned above may result from intrinsic trade-offs in insects.

Reduced wheat nutritional quality due to elevated CO2 concentration alters the cellular immune responses of cotton bollworm. Cellular responses in insects are mediated by the activity of circulating hemocytes, which participate in the encapsulation of parasite eggs and other invaders31. Alaux et al. (2010)14 indicated that hemocyte concentrations were increased in bees fed a diet without protein and further suggested that an investment in producing different types of hemocytes is costly, which would ultimately lead to an overall decrease in hemocyte numbers. In our study, we observed greater increases in THC and the spreading ability of hemocytes of cotton bollworm without parasites and fed on reduced quality wheat at the early sampled stage under elevated CO2. Consistent with our results, autumnal moth larvae fed on poor quality food apparently suffered from moderate nutritional stress compared to larvae fed on higher quality food and then increased their immune defense to a higher level10. Accordingly, we suggest that unparasitized cotton bollworm larvae fed on wheat of decreased nutritional quality grown under elevated CO2 apparently suffer from nutritional deficiency compared to larvae fed on grain grown under ambient CO2 and may therefore exhibit a stronger immune defense. In addition, the THC and spreading ability of hemocytes were all greater at the early sampling stage under elevated CO2, which suggests that the enhanced cellular immunocompetence is ephemeral. Longer sampling times may generate different results and further research should be conducted on this in the future.

Most published work has shown that plant nutritional quality affects the capacity of herbivorous insect larvae to encapsulate abiotic (e.g., experimental glass needles, chromatography beads and nylon threads) or biotic (e.g., insect eggs, larvae and nematodes) antigens10,32. After parasitization by M. mediator, the encapsulation ability was decreased under elevated CO2 during all measured time intervals, whereas the encapsulation ability was not significantly affected by decreases in the quality of wheat grown under the elevated CO2 in this study. Different from our results, Laurentz et al. (2012)33 showed that diet quality (increased catalpol concentrations) influences the encapsulation capability of Melitaea cinxia to defend against parasitoids and pathogens. Clearly, plant nutritional traits including primary- and secondary-chemistry affect the immune responses of herbivore insects. Further research should be conducted on how secondary-chemistry of wheat grown under elevated CO2 affects the immunocompetence of cotton bollworm.

Regardless of parasitization by M. mediator, decreases in the nutritional quality of wheat grain grown under elevated CO2 did not have a statistically significant effect on humoral immunity. We might have predicted that the greater number of hemocytes in cotton bollworm larvae that fed on higher quality food should have coincided with higher levels of PO activity because hemocytes produce some of the effector molecules used for humoral immunity including components of the PO cascade. However, we found that the baseline level of PO activity remained unchanged. Different from our results, several researches showed that individuals fed on poor-quality food exhibited higher PO activity than insects fed on higher quality food10,30. PO activity eventually leads to the production of melanin, a nitrogen-rich compound that may require substantial protein or nitrogen investment for its production34,35. Cuticular melanization are strongly dependent on the quantity of dietary protein ingested according to Lee et al. (2008)13. Their results implied that protein quality has a significant influence on the nitrogen pool that is potentially available for investment in melanization reaction. Based on their implications, depressed PO activity and impaired melanization reaction should be measured in our study. However, the lower N and protein contents of spring wheat grain grown under elevated CO2 are insufficient to influence PO activity and the rate of melanization of the host hemolymph.

Altered plant nutrition under elevated CO2 conditions affect the immune response of insect herbivores and further may influence natural enemy traits through “bottom up” effects. Several studies illustrate that plant quality can influence higher trophic levels in the same direction-,36,37,38, such that highly nutritional (or less defensive) plants increase the performance of both the insect herbivores and their natural enemies39. Other studies have shown opposite effects of plant quality on herbivorous insects and their natural enemies40,41; for example, nutrient deficiency and stress can reduce the general immunocompetence in insects against natural enemies42,43,44. Consistent with the above opposite effects, our results show that elevated CO2 levels decrease the immunity of cotton bollworm larvae that have been parasitized with M. mediator due to the reduced nutritional quality of the wheat. However, the lower immunocompetence of cotton bollworms did not change the development and parasitic traits of M. mediator. Although decreased plant quality can in theory compromise the immune responses of herbivores and increase the fitness of parasites, poor food plant quality is a major constraint on the development of immature parasites45.

In summary, our study demonstrates that decreased plant quality weakens the immunocompetence of the cotton bollworm H. armiger against its natural enemies (endoparasites) but is not sufficient to affect parasite emergence. The results of this study could have implications for the evolution of plant–herbivore–parasitoid interactions and emphasize the important role of the immune system and its variation based on host plant variation in bottom-up processes involving plants26. All in all, the role of elevated atmosphere CO2 in the herbivore insect immune function is poorly known, definitely requiring further investigation.

Methods

CO2 concentration

Open-top Chamber

This experiment was carried out using six octagonal open-top chambers (OTC), each 4.2 m in diameter, located at the Observation Station of the Global Change Biology Group, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Science (CAS) in Xiaotangshan County, Beijing, China (40°11′N, 116°24′E). The atmospheric CO2 concentrations used were 1) current ambient CO2 levels (375 μl/L) (“ambient CO2”) and 2) double the current ambient CO2 levels (750 μl/L) (“elevated CO2”). Six OTCs were used for each CO2 concentration treatment. During the period from seedling emergence to harvest, CO2 concentrations were monitored continuously using an infrared CO2 analyzer (Ventostat 8102, Telaire Company, USA) and adjusted every twenty minutes to maintain the assigned CO2 concentrations. The automatic control system used to adjust the levels of CO2 and the specifications for the open-top chambers are detailed in Chen et al. (2005)46.

Closed-dynamics CO2 Chamber

Insects were reared in a growth chamber (HPG280H; Orient Electronic, Harbin, China). Growth chamber conditions were maintained at 25 ± 1°C, 60–70% relative humidity, a photoperiod ratio of 14:10 (hours of light: hours of dark) and an active radiation of 9,000 lux (supplied by 1,260 W fluorescent lamps in each chamber). Two atmospheric CO2 concentrations (current ambient CO2 levels (375 μl/L) and double the current ambient CO2 levels (750 μl/L)) were maintained to match the OTCs used for wheat growth. Three chambers were used for each CO2 treatment. As previously mentioned, CO2 concentrations were automatically monitored using an infrared CO2 analyzer (Ventostat 8102; Telaire, Goleta, CA, USA) and adjusted. A detailed explanation of the methodology employed in the automatic control system for maintaining and adjusting the CO2 concentrations is described in Chen & Ge (2004)47.

Wheat variety and growth conditions

Spring wheat (Longfu174379 variety) was sown in plastic pots (height: 35 cm, diameter: 45 cm), in the six open-top chambers previously mentioned. Thirty-five pots were placed in each OTC. Pot placement was re-randomized in each OTC weekly. Pure CO2 was mixed with ambient air and supplied to each chamber throughout wheat development. During the milky-grain stage of spring wheat, ears and grains were harvested from all six OTCs and then refrigerated at −20°C until supplied to H. armigera as food.

Insect stocks

H. armigera egg masses were obtained from a laboratory colony maintained by the Insect Physiology Laboratory, Institute of Zoology at CAS and reared using wheat milky grains in a growth chamber. The temperature in each chamber was maintained at 25 ± 1°C, the relative humidity was 70 ± 10% and the photoperiod/scotoperiod ratio was 14:10 (hours of light: hours of dark).

M. mediator specimens were obtained from the Plant Protection Institute (PPI) of Hebei Academy of Agricultural and Forestry Sciences and were reared in a growth chamber using 15% hydromel (a fermentation of honey) as a food source. Growth chamber conditions were maintained exactly as described above.

Insect feeding

Elevated CO2 had little direct effect on cotton bollworms when fed on artificial diet9. Accordingly, H. armigera larvae were reared in growth chambers with ambient or elevated CO2 concentration, corresponding to their treatment levels. Within each CO2 concentration treatment group, larvae that reached the third larval instar were randomly divided in two lots. In the first lot, larvae were used to test changes of the immune response of their hemolymph at 24 h, 48 h, 72 h and 96 h after being parasitized by M. mediator. In the second lot, larvae that have not been parasitized were set as control for assay at each timestamp.

Inoculation with M. mediator

Newly formed third instar H. armigera larvae were parasitized and larvae with the same status were set as the control. To ensure that the larvae used in the experiments were successfully parasitized, one wasp and one larva were put in a vitreous tube and each larva was confirmed to be parasitized only once. Five replicates of twenty-four individuals each yielded a total of 120 insects studied for each treatment.

Observations of parasitized larvae of H. armigera in each CO2 treatment were recorded daily. M. mediator were retrieved from parasitized larvae, counted and weighed; the gender of the adults was determined upon emergence and the insects were then weighed. The ratios of adult emergence to non-emergence and of females to males were recorded. Newly emerged wasps were placed in cages and 15% hydromel was provided as a food source. Mated individuals were then housed in pairs (one female and one male) to determine adult longevity.

Chemical composition assay of wheat grains

Thirty grains of spring wheat were selected for each of the two CO2 treatments on three separate occasions, for a total of 90 grains. Water content was calculated as a proportion of fresh weight after the wheat grains were dried at 80°C for 72 hours. TNC, protein and total amino acid contents were measured according to the reagent protocol (Nanjing Jiancheng Ltd. Co., Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China). N content was assayed using the Kjeltec N analysis (Foss automated Kjeltec™ instruments, Model 2100).

Total hemocyte counts of hemolymph

H. armigera larvae were immersed in 70% alcohol for 5–10 s, washed with sterilized distilled water, dried and held in an ice bath for 10 s. Hemolymph was obtained from the host larvae by cutting their anterior part with opthalmic scissors. Hemolymph of parasitized and unparasitized larvae rared under ambient and elevated CO2 was collected at 24, 48, 72 and 96 h post parasitization.

Due to the small size of H. armigera larvae, the hemolymph from 15 individuals was pooled. THC was immediately measured in a hemocytometer and recorded as the number of hemocytes per 1 ml of hemolymph.

Hemocyte spreading and encapsulation in vitro

Spreading of hemocyte (sampled at 24, 48, 72 and 96 h post parasitization) was assayed by incubating 1 × 105 cells per well in 96-well culture plates (Flow Laboratories, Inc. USA) containing 70 μl of culture medium (SFX-Insect MP™, HyClone, Logan, UT). After incubation for 45 minutes, hemocyte spreading was observed using an inverted phase contrast microscope (Leica DM IRB, Leica). Finally, hemocytes were counted in three randomly chosen fields of view at 200 × magnifications and the number of spread cells was recorded. The spreading percentage of hemocyte cells was calculated as follows: % spreading = (number of spreading hemocyte cells observed)/(total number of hemocyte cells observed) × 100.

Host larvae at 24, 48, 72 and 96 h post parasitization were bled and the hemolymph collected was cultured as described for the spreading assay. Sephadex G-25 chromatography beads were used as encapsulation targets. In vitro encapsulation assays were carried out according to the procedure of Huang et al. (2009)18 by incubating 1 × 105 cells in 50 μl of medium per well in Linbro 96-well cell culture plates containing 10 Sephadex G-25 beads per well. The cultures were maintained at 27°C. After 24 h, the beads were observed under a Leica MZ 16A stereomicroscope and the number of encapsulated Sephadex G-25 beads was recorded. The encapsulation ratio of the hemocytes was calculated as follows: % encapsulation = (number of encapsulated Sephadex G-25 beads observed)/(total number of Sephadex G-25 beads) × 100.

Phenoloxidase activity

PO activity was assayed spectrophotometrically by using L-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA) as a substrate. 50 μl of larval hemolymph (sampled at 24, 48, 72 and 96 h post parasitization) were pre-incubated with an equal volume of the activator (1 mg/ml trypsin, 0.5 mg/ml laminarin) or for the controls, with cac-buffer (0.01 M sodium cacodylate buffer pH 7 containing 5 mM calcium chloride and 0.25 M sucrose) for 1 h at 20°C before adding 50 μl L-DOPA (3 g/L). The reaction was allowed to proceed for 10 min at 20°C. Enzyme activity was expressed as the change in absorbance at 490 nm per min and per mg protein (Huang et al. 2009)18.

The protein concentration of H. armigera larvae hemolymph was measured using the Bradford method48, with a standard curve created from a bovine serum albumin standard.

In vitro melanization reaction

To determine the capacity of the melanization reaction in the hemolymph of the host, host larvae were selected at designated times post parasitization or cortrol under both CO2 levels. Hemolymph samples from larvae were collected on a glass slide by puncturing the larval proleg with a sterile insect pin. The resulting drop of undiluted hemolymph was left for 20 min at ambient room temperature. A change in color of the hemolymph from opaque or green to brown-black, was recorded as normal melanization, whereas the maintenance of the previous color or a change to an intermediate color was considered to reflect inhibition of melanization49. The melanization ratio of hemocyte was calculated as follows: % melanization = (number of melanization reactions of larval hemolymph observed)/(total number of larval hemolymph sampled) × 100.

Data analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests (SPSS 17.0 for Windows; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) were used to analyze the effects of elevated CO2 on the chemical composition of spring wheat grains. Differences between means were compared using the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test. The data for parasitism rate and cocoon rate of M. mediator, as well as the emergence rate, weight and adult-longevity of M. mediator were also analyzed following the method described above. The THC, hemocyte spreading ratios, encapsulation ratios, PO activity, melanization ratios and the protein concentration of H. armigera larvae hemolymph were factors analyzed by ANOVA with CO2 levels as the main factor and designated times as sub-factor deployed in a split-plot design. The differences between means were determined using LSD test.

References

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate change 2007: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (eds Solomon, S. et al.), (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, USA, 2007).

Agrell, J., McDonald, E. P. & Lindorth, R. L. Effects of CO2 and light on tree photochemistry and insect performance. Oikos 88, 259–272 (2000).

Yin, J., Sun, Y., Wu, G., Parajulee, M. N. & Ge, F. No effects of elevated CO2 on the population relationship between cotton bollworm, Helicoverpa armigera Hübner (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and its parasitoid, Microplitis mediator Haliday (Hymenoptera: Braconidae). Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 132, 267–275 (2009).

Mattson, W. J. Herbivory in relation to plant nitrogen content. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 11, 119–161 (1980).

Johns, C. V. & Hugher, L. Interactive effects of elevated CO2 and temperature on the leaf-miner Dialectica scalariella Zeller (Lepidoptera: Gracillariidae) in Paterson's Curse, Echium plantagineum (Boraginaceae). Global Change Biol. 8, 142–152 (2002).

Stiling, P. et al. Decreased leaf-miner abundance in elevated CO2 lowers herbivore abundance, but increases leaf abscission rates. Global Change Biol. 8, 658–667 (1999).

Wu, G., Chen, F. & Ge, F. Response of multiple generations of cotton bollworm Helicoverpa armigera Hübner, feeding on spring wheat, to elevated CO2 . J. Appl. Entomol. 131, 2–9 (2006).

Chen, F. Wu, G., Parajulee, M. N. & Ge, F. Impacts of elevated CO2 and transgenic Bt cotton on performance and feeding of three generations of cotton bollworm in a long-term experiment. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 124, 27–35 (2007).

Yin, J., Sun, Y., Wu, G. & Ge, F. Effects of elevated CO2 associated with maize on multiple generations of the cotton bollworm, Helicoverpa armigera. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 136, 12–20 (2010).

Klemola, N., Klemola, T., Rantala, M. J. & Ruuhola, T. Natural host-plant quality affects immune defence of an insect herbivore. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 123, 167–176 (2007).

Klemola, N., Kapari, L. & Klemola, T. Host plant quality and defence against parasitoids: no relationship between levels of parasitism and a geometrid defoliator immunoassay. Oikos 117, 926–934 (2008).

Lee, K. P., Cory, J. S., Wilson, K., Raubenheimer, D. & Simpson, S. J. Flexible diet choice offsets protein costs of pathogen resistance in a caterpillar. Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. B 273, 823–829 (2006).

Lee, K. P., Simpson, S. J. & Wilson, K. Dietary protein-quality influences melanization and immune function in an insect. Funct. Ecol. 22, 1052–1061 (2008).

Alaux, C., Ducloz, F., Crauser, D. & Conte, Y. L. Diet effects on honeybee immunocompetence. Biol. Letters 6, 562–565 (2010).

Diamond, S. & Kingsolver, J. Host plant quality, selection history and trade-offs shape the immune response of Manduca sexta. Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. B 278, 289–297 (2011).

Povey, S., Cotter, S. C., Simpson, S. J., Lee, K. P. & Wilson, K. Can the protein costs of bacterial resistance be offset by altered feeding behaviour? J. Anim. Ecol. 78, 437–446 (2009).

Stanley, D. Prostaglandins and other eicosanoids in insects: biological significance. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 51, 25–44 (2006).

Huang, F., Shi, M., Yang, Y., Li, J. & Chen, X. Changes in hemocytes of Plutella xylostella after parasitism by Diadegma semiclausum. Arch. Insect. Biochem. Physiol. 70, 177–187 (2009).

Stettler, P., Trenczek, T., Wyler, T., Pfister-Wilhem, R. & Lanzrein, B. Overview of parasitism associated effects on host hemocytes in larval parasitoids and comparison with effects on their egg-larval parasitoid Chelonus inanitus on its host Spodoptera littoralis. J. Insect Physiol. 44, 817–831 (1998).

Carton, Y., Poirié, M. & Nappi, A. J. Insect immune resistance to parasitoids. Insect Sci. 15, 67–87 (2008).

Fitt, G. P. The Ecology of Heliothis Species in Relation to Agroecosystems. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 34, 17–53 (1989).

Wu, K. M. & Guo, Y. Y. The evolution of cotton pest management practices in China. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 50, 31–52 (2005).

Fajer, E. D., Bowers, M. D. & Bazzaz, F. A. The effects of enriched carbon dioxide atmospheres on plant-insect herbivore interactions. Science 243, 1198–1200 (1989).

Mattson, W. J. Herbivory in relation to plant nitrogen content. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 11, 119–161 (1980).

Brooks, G. L. & Whittaker, J. B. Responses of multiple generations of Gastrophysa viridula, feeding on Rumex obtusifolius, to elevated CO2 . Global Change Biol. 4, 63–75 (1998).

Vogelweith, F., Thiéry, D., Quaglietti, B., Moret, Y. & Moreau, J. Host plant variation plastically impacts different traits of the immune system of a phytophagous insect. Funct. Ecol. 25, 1241–1247 (2011).

Eleftherianos, I., ffrench-Constant, R. H., Clarke, D. J., Dowling, A. J. & Reynolds, S. E. Dissecting the immune response to the entomopathogen Photorhabdus. Trends Microbiol. 12, 552–560 (2010).

Cerenius, L. & Söderhäll, K. The prophenoloxidase-activating system in invertebrates. Immunol. Rev. 199, 116–126 (2004).

Siva-Jothy, M. T., Moret, Y. & Rolff, J. Insect immunity: an evolutionary ecology perspective. Adv. In. Insect. Phys. 32, 1–48 (2005).

Shikano, I., Ericsson, J. D., Cory, J. S. & Myers, J. H. Indirect plant-mediated effects on insect immunity and disease resistance in a tritrophic system. Basic Appl. Ecol. 11(1), 15–22 (2010).

Jiravanichpaisal, P., Lee, B. L. & Söderhäll, K. Cell-mediated immunity in arthropods: Hematopoiesis, coagulation, melanization and opsonization. Immunobiol. 211, 213–236 (2006).

Bukovinszky, T. et al. Consequences of constitutive and induced variation in plant nutritional quality for immune defence of a herbivore against parasitism. Oecologia 160, 299–308 (2009).

Laurentz, M. et al. Diet quality can play a critical role in defense efficacy against parasitoids and pathogens in the Glanville Fritillary (Melitaea cinxia). J. Chem. Ecol. 38, 116–125 (2012).

Blois, M. S. The melanins: their synthesis and structure. Photochemical and Photobiological Reviews (ed. Smith, K. C.) Vol. 3, pp. 115–134. (Plenum Press, New York, 1978).

Brakefield, P. M. Industrial melanism: do we have the answers? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2, 117–122 (1987).

Barbosa, P., Gross, P. & Kemper, J. Influence of plant allelochemicals on the tobacco hornworm and its parasitoid, Cotesia congregata. Ecology 72, 1567–1575 (1991).

Zvereva, E. L. & Rank, N. E. Host plant effects on parasitoid attack on the leaf beetle Chrysomela lapponica. Oecologia 135, 258–267 (2003).

Kagata, H., Nakamura, M. & Ohgushi, T. Bottom-up cascade in a tri-trophic system: different impacts of host-plant regeneration on performance of a willow leaf beetle and its natural enemy. Ecol. Entomol. 30, 58–62 (2005).

Kagata, H. & Ohgushi, T. Bottom-up trophic cascades and material transfer in terrestrial food webs. Ecol. Res. 21, 26–34 (2006).

Karowe, D. N. & Schoonhoven, L. M. Interactions among three trophic levels: the influence of host plant on performance of Pieris brassicae and its parasitoid, Cotesia glomerata. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 62, 241–251 (1992).

Holton, M. K., Lindroth, R. L. & Nordheim, E. V. Foliar quality influences tree-herbivore-parasitoid interactions: effects of elevated CO2, O3 and plant genotype. Oecologia 137, 233–244 (2003).

Brey, P. T. The impact of stress on insect immunity. Bulletin de l'Institut Pasteur 92, 101–118 (1994).

Suwanchaichinda, C. & Paskewitz, S. M. Effects of larval nutrition, adult body size and adult temperature on the ability of Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) to melanize Sephadex beads. J. Med. Entomol. 35, 157–161 (1998).

Rantala, M. J., Kortet, R., Kotiaho, J. S., Vainikka, A. & Suhonen, J. Condition dependence of pheromones and immune function in the grain beetle Tenebrio molitor. Funct. Ecol. 17, 534–540 (2003).

Harvey, J. A. & Tanaka, T. Intrinsic Inter-and Intraspecific Competition in Parasitoid Wasps. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 58, 333–351 (2013).

Chen, F., Ge, F. & Su, J. An improved open-top chamber for research on the effects of elevated CO2 on agricultural pests in field. Chinese J. Ecol. 23, 51–56 (2005).

Chen, F. & Ge, F. An experimental instrument to study the effects of changes in CO2 concentrations on the interactions between plants and insects-CDCC-1 chamber. Chinese Bull. Entomol. 41, 37–40 (2004).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976).

Doucet, D. & Cusson, M. Role of calyx fluid in alterations of immunity in Choristoneura fumiferana larvae parasitized by Tranosema rostrale. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 114A, 311–317 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by The Innovation Program of Chinese Academy of Science (KSCX2-EW-N-05), National Nature Science Fund of China (No. 31221091) and National Key Technology R&D Program (2012BAD19B05).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.G. and J.Y. designed the experiment. J.Y. and Y.S. performed the experiment. J.Y., Y.S. and F.G. wrote the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported license. The images in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the image credit; if the image is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the image. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yin, J., Sun, Y. & Ge, F. Reduced plant nutrition under elevated CO2 depresses the immunocompetence of cotton bollworm against its endoparasite. Sci Rep 4, 4538 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04538

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04538

This article is cited by

-

When warmer means weaker: high temperatures reduce behavioural and immune defences of the larvae of a major grapevine pest

Journal of Pest Science (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.