Abstract

Nm23-H1 is one of the most interesting candidate genes for a relevant role in Neuroblastoma pathogenesis. H-Prune is the most characterized Nm23-H1 binding partner and its overexpression has been shown in different human cancers. Our study focuses on the role of the Nm23-H1/h-Prune protein complex in Neuroblastoma. Using NMR spectroscopy, we performed a conformational analysis of the h-Prune C-terminal to identify the amino acids involved in the interaction with Nm23-H1. We developed a competitive permeable peptide (CPP) to impair the formation of the Nm23-H1/h-Prune complex and demonstrated that CPP causes impairment of cell motility, substantial impairment of tumor growth and metastases formation. Meta-analysis performed on three Neuroblastoma cohorts showed Nm23-H1 as the gene highly associated to Neuroblastoma aggressiveness. We also identified two other proteins (PTPRA and TRIM22) with expression levels significantly affected by CPP. These data suggest a new avenue for potential clinical application of CPP in Neuroblastoma treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neuroblastoma (NBL) is one of the most common pediatric solid tumors and it accounts for 15% of all pediatric cancer deaths. NBL originates from the sympathoadrenal lineage derived from the neural crest. The clinical course of NBL is markedly heterogeneous, as it can range from spontaneous regression or maturation, to more benign forms (e.g, ganglioneuroblastoma, ganglioneuroma), or to rapid tumor progression and patient death. The prognosis for NBL patients depends upon both clinical factors, including stage1, age at diagnosis2 and tumor histopathology3 and upon genetic factors, such as MYCN amplification (MNA) status4 and DNA index5.

Recent efforts to construct a novel tumor–risk stratification system for NBL have been based on the latest genome-wide genetic and gene expression profiling assays6,7,8,9,10. MNA status has been considered the most important prognostic factor for progressive disease and poor patient outcome11. In fact, advanced stage NBL and especially those with genomic amplification of the MYCN oncogene, is frequently resistant to any therapy. Thus, NBL is still one of the most challenging tumors to treat.

Nm23 was one of the first candidate genes to be identified on chromosome 17q. Its mRNA and protein expression is high in advanced NBL, combined with high protein levels in serum12. Indeed, amplification and overexpression of Nm23-H1 and also the S120G mutation of Nm23-H1 have been detected in 14% to 30% of patients with advanced NBL stages13,14. However, there is sufficient data showing that increased levels of Nm23-H1 correlate with decreased metastasis in most cancers15,16,17,18,19. While the mechanisms through which Nm23-H1 suppresses metastasis have been thoroughly deciphered20, the Nm23-H1 mechanism in the mediation of NBL aggressiveness remains to be understood.

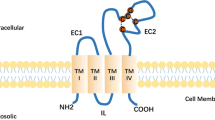

Several proteins that interact with Nm23-H1 have been identified and among these, h-Prune has been the best characterized. The h-Prune protein is a member of the phosphoesterases (DHH) protein superfamily and its overexpression in breast, colorectal and gastric cancers correlates with the degree of lymph-node and distant metastases21,22,23,24. The N-terminus of the h-Prune sequence contains the DHH (amino acids 10–180) and DHHA2 (amino acids 215-360) domains that are involved in its enzymatic functions. The inhibition of its phosphodiesterase (cAMP–PDE) activity with dipyridamole suppresses cell motility in breast cancer cell lines25,26,27. Of note, there is also an exopolyphosphatase (PPASE) activity within this N-terminus that includes the DHH domains28. The C-terminal region of h-Prune is responsible for its interaction with GSK-3β29 and with Nm23-H130. The Nm23-H1/h-Prune interaction is mediated through casein kinase phosphorylation of Ser120, Ser122 and Ser125 of Nm23-H131,32,33.

Our study focused on the role of Nm23-H1/h-Prune protein complex formation in NBL tumor progression and metastasis. On this basis, we characterized the three-dimensional model of the h-Prune C-terminal obtained using NMR and then we mapped the h-Prune surface regions involved in its interaction with Nm23-H1. We thus developed a competitive permeable peptide (CPP), which mimics the minimal region of interaction on Nm23-H132 and can bind to the C-terminal of h-Prune. Moreover we report a meta-analysis showing that NME1/NME2 are the genes highly connected to NBL aggressiveness in MNA-positive tumors. Furthermore, these findings highlight the roles of two additional proteins linked to the NME1/NME2 network whose expression level was found impaired by CPP: TRIM2234 and PTPRA35. In the present study, we show that the Nm23-H1/h-Prune C-terminal interaction regulates NBL tumorigenesis and that the impairment of this complex using CPP is a useful strategy for NBL treatment.

Results

h-Prune and Nm23-H1 mRNA levels in Neuroblastoma

To determine the expression levels of Nm23-H1 and h-Prune in human NBL, we searched through a public database (http://r2.amc.nl). This search revealed that Nm23-H1 (Fig. 1a) and h-Prune (Fig. 1b) are significantly overexpressed in NBL tissues compared to normal adrenal gland (p = 2.7 e−12 and 1.3 e−11, respectively). Moreover, we analyzed a cohort of 101 NBL samples (Essen database) showing that high expression of Nm23 (both H1 and H2) correlates significantly to poor survival (p = 9.9 e−10) (Fig. 1c). These results are in agreement with studies performed previously13,36. Although at the RNA level, h-Prune expression has not yet been significantly correlated to NBL survival from the previously analyzed cohorts, a positive association trend (p = 0.072) was seen (Fig. 1d). Taken together, these findings allow us to assume that the formation of the Nm23-H1/h-Prune complex is likely to have a role in cancer progression in NBL.

Nm23-H1 and h-Prune gene expression and NBL overall survival.

(a) NME1 expression in human NBL tissues (88 samples) compared to normal adrenal gland (13 samples) searched through a public database (Versteeg database). (b) H-prune expression in human NBL tissues compared to normal adrenal gland (Versteeg database). (c) In the Essen Affymetrix database, Nm23-H1 was detected with a probe which does not discriminate between Nm23-H1 and Nm23-H2. High expression of Nm23-H1/H2 in tumors promotes worse overall survival. (d) High expression of h-Prune in NBL tissues shows a trend towards worse overall survival that does not reach significance.

NMR and molecular dynamics structural studies of h-Prune C-terminus

The recombinant C-terminal domain of h-Prune (amino acids 354–453) is stable and soluble and it contains a disulfide bridge that links cysteines 419 and 437, as shown by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis (Fig. 2a). This domain has a low overall hydrophobicity and a high net negative charge and analyses according to several algorithms have suggested that it is mostly unfolded in the native protein. Far-UV circular dichroism spectrometry has confirmed this lack of secondary structure (see Supplementary Experimental Procedures). Western blotting revealed that the h-Prune C-terminal was sufficient for binding to the endogenous Nm23-H1 protein (Fig. 2b).

Three-dimensional model of h-Prune protein based on protein similarities at the N-H2 terminal domain region combined with NMR h-Prune C-terminal structural studies.

(a) The h-Prune C-terminal sequence. The amino acids given in bold represent those that are more exposed according to limited proteolysis experiments. (b) Affinity chromatography. His-tagged amino acids 354-453 of h-Prune was immobilized on the resin. SH-SY5Y and SH-SY5Y-Nm23-H1 total extracts were loaded as control. Elution E3 (from 200 mM imidazole) and E4 (from elution of the complex) were loaded. An anti-His antibody was used as control of immobilized protein. The anti-Nm23-H1 antibody shows that h-Prune C-terminal interacts with Nm23-H1. (c) The secondary chemical shift index, corrected for sequence-dependent contributions, based on1Hα,13Cβ,13Cα and13CO chemical shifts of the h-Prune C-terminal. Protein regions with a propensity to a helical structure (α1, α2 and α3) are highlighted. The1H-15N steady-state heteronuclear NOE values are also reported, according to the h-Prune C-terminal amino acids.

The chemical shift assignments (deposited into the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank with the accession number 19037) allowed an analysis of the secondary structure of the protein by comparison with random coil values corrected for local sequence effects. As shown in Figure 2c, multinuclear (Hα, Cβ, Cα, C′) chemical shift indexing (CSI) plots suggest that the majority of the resonances of the h-Prune C-terminal are within the random coil range. Nevertheless, the CSI values of the amino-acid sequences from Leu355 to Ser365 (α1 helical region), from Glu381 to Asp388 (α2 helical region) and from Leu428 to Gln439 (α3 helical region) are consistent with an α-helical secondary structure propensity. The CSI data are also supported by the 3JHNHA coupling-constant measurements, which are characteristic of unfolded molecules, with the exception of the three helical regions, which have means of 5.3 Hz, as typical of helical structures. To confirm these findings, other NMR parameters were measured, including the 15N relaxation rates (i.e., R1, R2 and 1H-15N nuclear Overhauser effects37) (see Supplementary Information).

A three-dimensional model of the full-length h-Prune protein was then built using an N-terminal (amino acids 1–352) h-Prune structure derived via homology modeling and attached to a representative NMR h-Prune C-terminal structure. The full-length h-Prune model was then refined through molecular dynamics simulation in vacuo. The analysis of the whole structure indicates that the N terminus (amino acids 353–370) of the h-Prune C-terminal (Fig. 3a–c) is indeed part of the h-Prune DHH2 domain and in particular constitutes the second part of the last helix and a turned region that interacts with the preceding helix; accordingly, this region in the h-Prune C-terminal has a clear helical propensity (Fig. 2c). Therefore, the IDP h-Prune C-terminal domain that does not have specific interactions with the globular portions of the whole protein begins at residue 371 and retains the secondary structure propensities (α2 and α3) indicated by the NMR analysis, with a more compact C-terminal region (amino acids 410–440; see Movie 1).

Three-dimensional model of full-length h-Prune.

(a) The amino acids showing large variations upon complex formation with Nm23-H1 and the CPP peptide are mapped in cyan. The regions colored in magenta correspond to the amino acids recognized exclusively by Nm23-H1, as shown in detail in panels b and c.

Then the interaction of Nm23-H1 and CPP with h-Prune C-terminal was also followed via chemical shift mapping (see Supplementary Information). These results map the site of interaction between Nm23-H1 and the h-Prune C-terminal region in detailed molecular dimensions; further studies will address these protein-protein regions of interaction for therapeutic purposes, starting from an in-vitro analysis in NBL.

Functional studies of the Nm23-H1 binding site of h-Prune

These NMR methodologies have identified the most significant amino acids of the h-Prune C-terminal region involved in binding to Nm23-H1. We then undertook a functional analysis of three of the most conserved amino acids (D388, D422 and C419) (Fig. 4a). The amino acids were mutated to alanine, alanine and serine, respectively. Then, we evaluated their functions on HEK293 cells in two-dimensional cell-migration assays (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 1e). Overexpression of the h-Prune-D388A and h-Prune-D422A mutated proteins did not induce cell migration, as shown by empty-vector-transfected cells, compared to the full-length h-Prune wild-type transfected cells. The affinity chromatography in Fig. 4c shows that the D388A and D422A mutant h-Prune proteins interact weakly with Nm23-H1. Moreover, the h-Prune-C419S mutant did not affect cell motility to the same extent (Supplementary Fig. 1f,g), thus indicating direct correlation of protein complex formation and enhancement of cell motility.

Migration assays to assert migration properties of differential protein domains of the h-Prune protein.

(a) Alignment of the h-Prune C-terminal. Amino acids involved in Nm23-H1 binding are highlighted in yellow. (b) Two-dimensional invasion assay. HEK293 cells transfected with h-Prune mutant proteins (D388A and D422A) showed decreased migration ability. Data are represented as relative (fold) increases in the number of cells migrating compared to full-length h-Prune wild-type transfected cells. (c) Affinity chromatography. The His-tagged 354-453 h-Prune D422A mutant (upper) and D388A mutant (lower) were immobilized on the resin. HEK293 total extract was loaded as control. An anti-His antibody was used as control for the protein immobilized. An anti-Nm23-H1 antibody shows that the mutated 354–453 h-Prune interacts weakly with Nm23-H1. (d) Affinity chromatography. SH-SY5Y pre-infected cells (Ad-CPP) were loaded onto the chromatography column and the eluates were loaded onto acrylamide gels. Nm23-H1 was detected using an anti-Nm23-H1 antibody. Protein 373–353 h-Prune was revealed using an antibody against the His tag. (e) Following Ad-CPP and Ad-Mock infections in SH-SY5Y and SK-N-BE cells, the protein levels of phospho-Nm23-H1, Nm23-H1 and anti-h-Prune were analyzed by Western blotting. β-Actin was used as the loading control. (f) Two-dimensional migration assay of NBL cells showing that CPP overexpression reduces the migratory properties of both SH-SY5Y and SK-N-BE cells.

CPP impairs the Nm23-H1/h-Prune C-terminal interaction

Next, we addressed the use of the CPP (Supplementary Fig. 4a) to determine its therapeutic properties in vitro and in vivo in NBL. We thus infected SH-SY5Y cells with adenovirus particles carrying CPP (Ad-CPP) and initially validated its expression (Supplementary Fig. 4b,c). The expression of the CPP impaired the binding between Nm23-H1 and h-Prune, as assessed by affinity chromatography (Fig. 4d) and decreased the amount of phosphorylated Nm23-H1 (Fig. 4e). However, the same was not seen in SK-N-BE. In both of these cell lines, the levels of the Nm23-H1 and h-Prune proteins were not changed upon Ad-CPP expression. Also, in other cell lines tested, only a weak decrease in the levels of phosphorylated Nm23-H1 was seen (Supplementary Fig. 4e). These data can be explained considering differential levels of endogenous phosphorylation of Nm23-H1 at S122 and S125 in these cancer cells. Then, we assayed the CPP effect on cellular motility in NBL cells and we observed a significant impairment of cellular motility compared to adenovirus mock-infected cells (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 4g). These data are of particular pharmacological impact, especially as they were obtained on two independent NBL cell lines.

In vivo functional studies of CPP in xenograft models of NBL tumorigenesis

CPP function was then investigated in NBL xenograft animal model. Ad-treated SH-SY5Y cells were injected into the flanks of athymic nude mice. After 4 weeks, the tumors were explanted and the inhibition of tumor growth by CPP reached significance (p = 0.00098), as compared to mock-treated SH-SY5Y mice (Fig. 5a). Moreover, tumors obtained from the Ad-CPP-treated SH-SY5Y mice showed a reduction in the expression of the phosphorylated Nm23-H1 protein, while the levels of the Nm23-H1 and h-Prune proteins did not changed, confirming the in vitro data (Fig. 5b). We also assayed two groups of heterotopic xenograft mice that were injected with SH-SY5Y-Luc cells (expressing the luciferase gene) previously infected with Ad-CPP or the control Ad-Mock; tumorigenesis was followed using in vivo biolumuniscence imaging (BLI) technology, over four weeks. The mice receiving Ad-CPP-treated SH-SY5Y-Luc cells (7 mice) showed significant reduction of tumor burden (Fig. 5c) compared to the control treated group (Ad-Mock, 7 mice). This result was confirmed in the quantified data that were obtained by counting the total photon emission (BLI) through whole-body analyses (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Table 1). The tumors generated from Ad-CPP-treated cells showed reduced size and reduced positive staining for both Nm23-H1 and h-Prune compared to Ad-Mock mice. In the Ad-CPP-treated tissues, we also observed positive staining for the neuronal marker, Tuj1, as a sign of benign neuronal differentiation processes and minimal Caspase3 activation (Fig. 5e). These data illustrate the therapeutic benefit of the use of CPP in vivo.

In vivo functional effect of CPP expression.

(a) Representative explanted tumors. Tumor weight data are presented as means ± standard deviation. (b) Proteins extracted from tumor tissues were loaded onto acrylamide gels to evaluate the protein expression levels of phospho-Nm23-H1, Nm23-H1 and h-Prune. β-Actin was used as the loading control. (c, d) Two NOD/SCID mice groups were given intra-adrenal gland injections of SH-SY5Y-luc cells previously infected with Ad-Mock (7 mice) or Ad-CPP (7 mice). Tumorigenesis was followed by in-vivo bioluminescence photon emissions signals (IVIS Imaging System). Cells pre-infected with Ad-CPP showed impaired tumor growth, with respect to controls. (e) Photograph of resected tumors and representative images of the immunostaining for Ha-Tag, Nm23-H1, h-Prune, Tuj1 and Caspase 3.

Nm23-H1 correlates with aggressive human neuroblastoma

In order to discover the genes related to Myc activity and to investigate how these genes might interact, we performed meta-analysis of data from two different datasets and produced a network (see Supplementary Information). In this network, NME1 and NME2 resulted the most connected genes to NBL aggressiveness (Fig. 6a). In addition to these genes, PTPRA, NTRK1, PHGDH and LAPTM4B are also highly connected.

A common molecular network for NBL aggressiveness, derived by meta-analysis, combining gene expression NBL databases from two different studies.

(a) Two microarray datasets were analysed: Cologne 2-Color (251 samples) and Essen Affymetrix (76 samples). In the network, the NME1 gene is the most connected. Nodes represent genes; node size represents the degree of the node (i.e., the number of connections it has). Nodes are connected with lines, which represent interactions between genes. Line thickness represents the strength of interactions, as measured by mutual information. Statistical confidence of the interactions is represented by the opacity of the color of the lines (strong gray, most reliable interactions; light gray, least reliable interactions). (b) Proteins extracted from tumor tissues and SH-SY5Y cells were loaded on acrylamide gels to determine the protein expression levels of TRIM22 and PTPRA. β-Actin was used as the loading control. Action view of gene networks of genes that are highly correlated with Trim22 (c, green) and PTPRA (d, green). Modes of action are shown in different colors. Genes highlighted in yellow were further investigated. (e) Western blotting showing CPP effects on the Akt pathway in SH-SY5Y cells. β-Actin was used as the loading control. (f) Western blotting for activated β-Catenin, c-Myc, P-Ikbα and Ikbα protein levels in SH-SY5Y cells after CPP overexpression. β-Actin was used as the loading control. (g) Following Ad-CPP infections in SH-SY5Y cells, protein levels of EGFR, Paxillin, Fak, Fak (Y397), Grb2 and Src (Y527) were analyzed by Western blotting. β-Actin was used as the loading control.

Then, we investigated whether overexpression of CPP in SH-SY5Y cells impairs mRNA expression levels of these identified connected genes. Among the genes analyzed, TKT, RPL4, TRIM2238 and PTPRA39 mRNA expression levels were significantly affected by CPP overexpression (Supplementary Fig. 5a). TRIM22 and PTPRA were further analyzed. Also, upon CPP overexpression in SH-SY5Y cells, the mRNA and protein levels of TRIM22 decreased, both in vitro and in vivo. Interestingly, although CPP markedly increased the mRNA levels of PTPRA, the protein levels of PTPRA were actually reduced (Fig. 6b). Thus it appears that an increase in PTPRA mRNA expression does not translate into an appropriate increase in its protein levels.

We then asked whether CPP has any effects on genes related to TRIM22 and PTPRA in NBL. For this reason, in a public database we searched the set of genes positively correlated to TRIM22 and PTPRA (see Supplementary Information). The selected genes were used to obtain a molecular network using STRING analyses (Fig. 6c,d). TRIM22 was correlated to genes involved in apoptosis, inflammation and cell proliferation. To investigate the effects of perturbation of the TRIM22 network by CPP overexpression, we performed Western blotting. This showed the impairment of the Akt signaling pathway, as there was decreased phosphorylation of Akt (Ser473) and increased levels of Pten (Fig. 6e). Among the TRIM22-connected genes, we found beta-transducin-repeat-containing protein (BTRC) involved in the proteasomal degradation of β-Catenin and Iκb-α40. We observed that upon CPP treatment, the levels of active β-Catenin (dephosphorylated on Ser37 and Thr41) and its target gene C-Myc decreased; this is in agreement with the diminished levels of phospho-Iκb-α (Ser32/36) (Fig. 6f).

The network of genes related to PTPRA appears to be mainly involved in cellular motility. Indeed, PTPRA can dephosphorylate Tyr527 of c-Src in vitro and this can lead to increased c-Src kinase activity and transformation once overexpressed. Here, we showed that the overexpression of CPP in SH-SY5Y cells leads to reduction in EGFR, Fak (Y397) and the adaptor protein Grb2 (Fig. 6g). Moreover, decreased PTPRA leads to increased phosphorylation of c-Src (Tyr527), thus reducing further c-Src activity and thus resulting in a reduction in cell motility.

Overall, our data show that the network proteins within the Nm23-H1/h-Prune protein complex pointing to PTPRA and TRIM22 are negatively regulated using CPP.

Discussion

Despite the aggressive treatment strategies, for patients with NBL the five-year survival rate for metastatic disease is still less than 60% and consequently, novel therapeutic approaches are needed.

Protein–protein interactions are essential in every aspect of cellular activity and the discovery of many small molecules that can modulate such interactions is an attractive aim for the design of new agents that will represent new drugs. Together, Nm23-H1 and h-Prune form a protein complex that is part of a network not yet fully known. H-Prune has been shown to be a marker of aggressiveness in breast cancer, as well in other cancers22,24,31 and to date its tumor function has been correlated mainly to its cAMP-PDE activity. Nm23-H1 is a well-known metastasis suppressor in breast cancer and it binds to the C-terminal region of the h-Prune protein upon CKI phosphorylation.

In NBL, elevated expression of Nm23-H1 is correlated to poor survival and to the overexpression of N-Myc, which is a negative diagnostic biomarker20. In the present study, to underline the negative functions of Nm23-H1 in NBL, meta-analyses of functional genomic analyses combined with gene expression data showed further stratification of the subtypes of aggressive NBL tumors. We have seen here that Nm23-H1 functions as a central node of these MYC-N-positive tumors, together with other genes where up-regulation promotes tumorigenesis. A validation of these results was further obtained by analyzing an additional gene expression database where, as expected, the expression of these genes correlated with bad clinical outcome in NBL. We further identified two new genes in the network that are unbalanced followed CPP treatment, TRIM22 and PTPRA, the expression of which is associated with poor prognosis. Looking at the public database, we selected a list of genes that positively correlated with TRIM22 and PTPRA in NBL, thus obtaining new gene networks, in turn unbalanced by CPP.

Here, we represent these findings by the model outlined in Figure 7. Although the exact Nm23-H1 mechanism of action for the mediation of NBL aggressiveness is not completely understood, the data presented here supports the concept that Nm23-H1, through the binding with h-Prune, could act as pro-metastatic gene. In silico data demonstrates that Nm23-H1 was also overexpressed in Th-ALKF1174 41 and Lin28b37 transgenic mice (Supplementary Fig. 9b). Those results are of importance because CPP was already found impairing the same pathways (Fig. 6), hence arguing its efficacy in future experiments using genetic animal model of NBL.

Status of N-MYC/Nm23-H1 high and h-Prune NBL tumors and a model of action of CPP.

(a) Level of phosphorylation of Nm23-H1 and complex formation through the h-Prune C-terminal has prognostic relevance for determining an aggressive NBL phenotype and thus worse outcome. (b) Use of the mimetic peptide CPP which can impair the binding of Nm23-H1 and h-Prune in vitro and in vivo, resulting in substantial impairment of cell motility and metastatic niche formation in vivo, with therapeutic benefit. This is accompanied by inhibition of the WNT, NF-κb, AKT and FAK intracellular signaling pathways.

A structural analysis by means of combined NMR, homology modelling and molecular dynamics has shown that h-Prune has two globular domains, DHH and DHH2 and an IDP domain, which contains two stretches (α2 and α3) which have clear propensity to fold as helices and a small globular region (amino acids 413–439) that is constrained by the disulfide bridge and which includes α3. The h-Prune interaction with Nm23-H1 is mediated by the IDP domain, particularly through the small globular region and by amino acids 387–396, including the α2 C-terminus (Fig. 3). This suggests that in the Nm23-H1/C-terminal h-Prune complex, the entropic cost of approaching the amino acid 387–396 region to the globular region will probably be balanced by the enthalpic contribution of the interaction between Nm23-H1 and the h-Prune C-terminal globular region. Interestingly, the h-Prune C-terminal interaction surface, seen as the smaller CPP, preserves most of the amino acids of the 387–396 region but a much smaller part of the C-terminal globular region. Therefore, covalent linking of a molecular binder of the h-Prune C-terminal globular region to CPP represents a promising route for the development of a lead compound that can impair the Nm23-H1/h-Prune interactions with a pharmaceutical aim. However, the results seen here in vitro show that a single mutation is sufficient to impair such interactions. The occurrence of an IDP of significant size (>50 amino acids) is surprisingly common in functional proteins42. Their functions include regulation of transcription and translation, cell-signal transduction, protein phosphorylation, the storage of small molecules and regulation of the self-assembly of large multi-protein complexes43. How this IDP structure will assemble with other proteins in the network is issue of future studies. The overexpression of Nm23-H1 and h-Prune enhances the aggressiveness of NBL cells in vitro and in vivo. In mouse orthotopic xenograft models of NBL, Nm23-H1 and h-Prune enhance the formation of metastatic foci, which suggests that when the complex is forced from both sides, the cells became more aggressive compared to the control NBL cell lines.

As CPP is a mimetic peptide of a phosphorylated domain of Nm23-H1, it might impair the interactions of Nm23-H1 with several other proteins, while impairing other biological function in the cells. Moreover, in other cellular systems where high expression of Nm23-H1 is associated with good prognosis, the impairment of phosphorylation-mediated functions by the use of CPP might not provide a relevant therapeutic strategy. For this reason, we investigated the contributions of putative amino acid interaction regions on h-Prune as sufficient to stabilize the pro-motility ability of the complex. This observation is issue of future laboratory investigations. Meanwhile, by applying the power of meta-analysis, we propose here a network that is further regulated by CPP in vivo and in vitro. Thus impairing this protein complex (Nm23-H1/h-Prune) with CPP results not only in impaired cell motility in vitro, but also, impaired tumorigenesis and metastasis formation in vivo, all of which are processes that are in turn further linked to the expression of the genes related within this network, as strongly predicted by meta-analysis statistical efforts.

Our data presented here suggest that the therapeutic application of CPP should be relevant for the treatment of the tumors characterized by the chromosome 17q gain, MYC-N amplification, ALK mutations which highly expresses Nm23-H1, together with the altered linked network genes (PTPRA and TRIM22). These selected tumors and hence patients, could have a definitive benefit from CPP treatment. Further novel treatment modalities like this peptidomimetic approach and innovative drug delivery systems such as the use of liposomes should improve the treatment of the high-risk group of NBL, as well as decrease the number of late side effects.

Methods

Adenovirus constructs and infection

The Nm23-H1 region (aa.115–128) was 5′-XhoI, 3′-HindIII synthesized downstream in-frame to the HA epitope sequence and upstream of the TAT protein sequence. The sequence coding the peptide, called CPP, was directly cloned into the VQ Ad5CMV K-NpA shuttle vector, supplied by ViraQuest (North Liberty, IA, USA), which provided its recombination and the CPP adenovirus construct (Ad-CPP) with a solution of 1012 virus particles/ml. They also supplied the control backbone E3 luciferase virus, generated from a VQ Ad5CMVeGFP plasmid. Infection with recombinant viruses was accomplished by exposing the cells (100 MOI/cell) to adenovirus in 500 μl complete cell culture medium for 1 h, followed by addition of other medium.

In vivo xenograft model

Human NBL SH-SY5Y cells were stably transfected with a pLentiV5-luciferase-expressing vector (Invitrogen) as described elsewhere44. SH-SY5Y-LUC clones were grown under standard conditions in DMEM containing 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine and 5 μg/ml blasticidine for selection. The cells were infected with 100 MOI of the specified virus (adenovirus type 5) following standard protocols. 48 hours later, the cells were harvested and 2 × 106 infected SH-SY5Y-LUC cells in 10 μL PBS solution were inoculated into the left adrenal glands of five-week-old female athymic nude mice (Harlan Laboratories). Tumor cell growth was monitored weekly, as described by45, measuring luminescence emission, using the IVIS 3D Illumina Imaging System (Perkin Elmer, USA). Quantitative data analysis of the tumor size was performed and evaluated by ANOVA statistical tests, using the Statview program, version 5.0.1. Mice experiments were conducted according to Institutional Animal Care and Ethical Committee of CEINGE-University of Naples ‘Federico II’ (Protocol 29, September 30, 2009) and of the Italian Ministry of Health (Dipartimento Sanità Pubblica Veterinaria D.L. 116/92).

Wound healing assay and two-dimensional migration assay

HEK293 and NBL cells (SH-SY5Y and SK-N-BE) were transfected with the previously described plasmids. After 24 h from transfection, the cells were scratched and after 12 h the ability of the cells to cover the wound was assessed. Images were taken using bright-light microscopy. To performed the motility assay, the cells were trypsinized, counted and seeded into transwell inserts in the presence of 2% fetal bovine serum, with treated polycarbonate membrane (Corning Incorporated Costar). The migration toward the bottom of the insert driven by the presence of 6% fetal bovine serum was stopped after 2 h. The cells on the membrane were washed in PBS, fixed in acetic acid (5%) and ethanol (95%) and stained with Hematoxilin & Eosin. The membrane images were acquired using a photocamera and the stained cells were counted using the ImageJ software.

Orthotopic xenografts of NBL SH-SY5Y cells

SH-SY5Y cells were infected with 100 MOI of the specified virus (adenovirus type 5) following standard protocols. 24 hours later, the cells were harvested and 2 × 106 infected SH-SY5Y-LUC cells, in 100 μl PBS solution, were implanted in the flanks of athymic nude mice (Harlan Laboratories). Tumors were explanted four weeks after injection and their weight was misured. The tissues were then homogenized for 2 × 3 min with TissueLyser (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer instructions and lysed in protein lysis buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Na-deoxycholate and 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche). Tissues lysates (50 μg) were electrophoresed on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore).

Western blotting

Cells were washed in cold phosphate-buffered saline and lysed in protein lysis buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Na-deoxycholate and 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche). Cell lysates (50 μg) were electrophoresed on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore). After 1 h blocking with 5% dry milk fat in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.02% Tween-20, the membranes were incubated with the primary antibody overnight at 4°C and with the secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The bands were visualized with a chemiluminescence detection system (Pierce), according to the manufacturer instructions. The antibodies used were as follows: anti-Nm23-H1 (Santacruz sc-343), anti-c-Myc (Santacruz sc-47694), anti-β-catenin (Millipore 05-665), anti-p-IkB-α (ser32/36) (Santacruz sc-101713), anti-Flag (Sigma A2220), anti-β-actin (Sigma A 5441), anti-FAK (Abcam ab40794), anti-Fak (phospho Y397) (Abcam ab4803), anti-p-Akt (ser473) (Cell Signaling 4060), anti-TRIM22 (Sigma HPA003575) and anti-PTPRA (Sigma HPA029412).

Statistical analyses

All biochemical experiments were done in triplicate unless otherwise stated. Two-tailed Student's t test was used to test significance. Statistical significance was established at *P ≤ 5 × 10−2, **P ≤ 5 × 10−4, ***P ≤ 5 × 10−6. Survival curves were constructed by the Kaplan and Meier method, with differences between curves tested for statistical significance using the log-rank test.

References

Brodeur, G. M. et al. Revisions of the international criteria for neuroblastoma diagnosis, staging and response to treatment. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 11, 1466–1477 (1993).

Breslow, N. & McCann, B. Statistical estimation of prognosis for children with neuroblastoma. Cancer research 31, 2098–2103 (1971).

Shimada, H. et al. International neuroblastoma pathology classification for prognostic evaluation of patients with peripheral neuroblastic tumors: a report from the Children's Cancer Group. Cancer 92, 2451–2461 (2001).

Seeger, R. C. et al. Association of multiple copies of the N-myc oncogene with rapid progression of neuroblastomas. The New England journal of medicine 313, 1111–1116 (1985).

Look, A. T. et al. Clinical relevance of tumor cell ploidy and N-myc gene amplification in childhood neuroblastoma: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 9, 581–591 (1991).

Abel, F. et al. A 6-gene signature identifies four molecular subgroups of neuroblastoma. Cancer cell international 11, 9 (2011).

De Preter, K. et al. Meta-mining of neuroblastoma and neuroblast gene expression profiles reveals candidate therapeutic compounds. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 15, 3690–3696 (2009).

Diskin, S. J. et al. Common variation at 6q16 within HACE1 and LIN28B influences susceptibility to neuroblastoma. Nature genetics (2012).

Fieuw, A. et al. Identification of a novel recurrent 1q42.2-1qter deletion in high risk MYCN single copy 11q deleted neuroblastomas. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer 130, 2599–2606 (2012).

Schramm, A. et al. Next-generation RNA sequencing reveals differential expression of MYCN target genes and suggests the mTOR pathway as a promising therapy target in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer (2012).

Theissen, J. et al. Heterogeneity of the MYCN oncogene in neuroblastoma. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 15, 2085–2090 (2009).

Okabe-Kado, J. et al. Clinical significance of serum NM23-H1 protein in neuroblastoma. Cancer science 96, 653–660 (2005).

Almgren, M. A., Henriksson, K. C., Fujimoto, J. & Chang, C. L. Nucleoside diphosphate kinase A/nm23-H1 promotes metastasis of NB69-derived human neuroblastoma. Molecular cancer research: MCR 2, 387–394 (2004).

Garcia, I. et al. A three-gene expression signature model for risk stratification of patients with neuroblastoma. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 18, 2012–2023 (2012).

Liu, F., Zhang, Y., Zhang, X. Y. & Chen, H. L. Transfection of the nm23-H1 gene into human hepatocarcinoma cell line inhibits the expression of sialyl Lewis X, alpha1,3 fucosyltransferase VII and metastatic potential. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology 128, 189–196 (2002).

Steeg, P. S., Bevilacqua, G., Pozzatti, R., Liotta, L. A. & Sobel, M. E. Altered expression of NM23, a gene associated with low tumor metastatic potential, during adenovirus 2 Ela inhibition of experimental metastasis. Cancer research 48, 6550–6554 (1988).

Leone, A., Flatow, U., VanHoutte, K. & Steeg, P. S. Transfection of human nm23-H1 into the human MDA-MB-435 breast carcinoma cell line: effects on tumor metastatic potential, colonization and enzymatic activity. Oncogene 8, 2325–2333 (1993).

Miyazaki, H. et al. Overexpression of nm23-H2/NDP kinase B in a human oral squamous cell carcinoma cell line results in reduced metastasis, differentiated phenotype in the metastatic site and growth factor-independent proliferative activity in culture. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 5, 4301–4307 (1999).

Leone, A. et al. Reduced tumor incidence, metastatic potential and cytokine responsiveness of nm23-transfected melanoma cells. Cell 65, 25–35 (1991).

Steeg, P. S., Zollo, M. & Wieland, T. A critical evaluation of biochemical activities reported for the nucleoside diphosphate kinase/Nm23/Awd family proteins: opportunities and missteps in understanding their biological functions. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's archives of pharmacology 384, 331–339 (2011).

Massidda, B. et al. Molecular alterations in key-regulator genes among patients with T4 breast carcinoma. BMC cancer 10, 458 (2010).

Noguchi, T. et al. h-Prune is an independent prognostic marker for survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Annals of surgical oncology 16, 1390–1396 (2009).

Oue, N. et al. Increased expression of h-prune is associated with tumor progression and poor survival in gastric cancer. Cancer science 98, 1198–1205 (2007).

Zollo, M. et al. Overexpression of h-prune in breast cancer is correlated with advanced disease status. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 11, 199–205 (2005).

D'Angelo, A. et al. Prune cAMP phosphodiesterase binds nm23-H1 and promotes cancer metastasis. Cancer cell 5, 137–149 (2004).

D'Angelo, A. & Zollo, M. Unraveling genes and pathways influenced by H-prune PDE overexpression: a model to study cellular motility. Cell cycle 3, 758–761 (2004).

Spano, D. et al. Dipyridamole prevents triple-negative breast-cancer progression. Clinical & experimental metastasis (2012).

Tammenkoski, M. et al. Human metastasis regulator protein H-prune is a short-chain exopolyphosphatase. Biochemistry 47, 9707–9713 (2008).

Kobayashi, T. et al. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 and h-prune regulate cell migration by modulating focal adhesions. Molecular and cellular biology 26, 898–911 (2006).

Garzia, L. et al. H-prune-nm23-H1 protein complex and correlation to pathways in cancer metastasis. Journal of bioenergetics and biomembranes 38, 205–213 (2006).

Forus, A. et al. Amplification and overexpression of PRUNE in human sarcomas and breast carcinomas-a possible mechanism for altering the nm23-H1 activity. Oncogene 20, 6881–6890 (2001).

Garzia, L. et al. Phosphorylation of nm23-H1 by CKI induces its complex formation with h-prune and promotes cell motility. Oncogene 27, 1853–1864 (2008).

Reymond, A. et al. Evidence for interaction between human PRUNE and nm23-H1 NDPKinase. Oncogene 18, 7244–7252 (1999).

Hatakeyama, S. TRIM proteins and cancer. Nature reviews. Cancer 11, 792–804 (2011).

Jiang, G. et al. Dimerization inhibits the activity of receptor-like protein-tyrosine phosphatase-alpha. Nature 401, 606–610 (1999).

Godfried, M. B. et al. The N-myc and c-myc downstream pathways include the chromosome 17q genes nm23-H1 and nm23-H2. Oncogene 21, 2097–2101 (2002).

Molenaar, J. J. et al. LIN28B induces neuroblastoma and enhances MYCN levels via let-7 suppression. Nature genetics (2012).

Obad, S. et al. Staf50 is a novel p53 target gene conferring reduced clonogenic growth of leukemic U-937 cells. Oncogene 23, 4050–4059 (2004).

Zhang, X. Q. et al. Receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase alpha signaling is involved in androgen depletion-induced neuroendocrine differentiation of androgen-sensitive LNCaP human prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 22, 6704–6716 (2003).

Fuchs, S. Y., Spiegelman, V. S. & Kumar, K. G. The many faces of beta-TrCP E3 ubiquitin ligases: reflections in the magic mirror of cancer. Oncogene 23, 2028–2036 (2004).

Berry, T. et al. The ALK(F1174L) mutation potentiates the oncogenic activity of MYCN in neuroblastoma. Cancer cell 22, 117–130 (2012).

Tompa, P. On the supertertiary structure of proteins. Nature chemical biology 8, 597–600 (2012).

Tantos, A., Han, K. H. & Tompa, P. Intrinsic disorder in cell signaling and gene transcription. Molecular and cellular endocrinology 348, 457–465 (2012).

Garzia, L. et al. MicroRNA-199b-5p impairs cancer stem cells through negative regulation of HES1 in medulloblastoma. PLoS One 4, e4998 (2009).

de Antonellis, P. et al. MiR-34a targeting of Notch ligand delta-like 1 impairs CD15+/CD133+ tumor-propagating cells and supports neural differentiation in medulloblastoma. PLoS One 6, e24584 (2011).

Acknowledgements

For critical discussions, help in devoloping previous data and for helpful suggestions, the authors would like to thank (in alphabetical order): Alessandra Andrè, AnnaMaria Bello, Richard Cambdam, Anna D'Angelo, Luigi Del Vecchio & FACS Service Facility CEINGE, Alessia Galasso, Cristin Roma, Frank Speleman, Angelo Taglialatela, Luigi Terracciano, GianPaolo Tonini and Jo Vandesopele. Financial support: PRIN (E5AZ5F) 2008 (MZ), AIRC (MZ), FP6-EET pipeline LSH-CT-2006-037260 (MZ), FP7- Tumic HEALTH-F2-2008-201662 (MZ), Fondazione italiana per la lotta al Neuroblastoma (MZ); MC is supported by Dottorato in Biologia Computazionale e Bioinformatica, Federico II of Naples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived the experiments: A.E., G.A., G.B., R.F., S.D., M.Z. Designed the experiments: M.C., P.d.A., D.D., E.P., M.Z. Performed the experiments: M.C., E.P., D.D., M.N.S., F.C., P.d.A., N.M., L.N., V.D.D., S.C., L.P., S.M.M., B.A. Analyzed the data: M.C., P.d.A., E.P., D.D., S.D., I.S., B.Z., R.F., M.P., J.H.S., A.S., A.E., F.P., F.W., G.A., B.A., G.B., M.S., E.B., M.Z. Contributed reagents/materials: M.Z. Supervised the design and experiments and wrote the paper: M.Z. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

movie 1

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Carotenuto, M., Pedone, E., Diana, D. et al. Neuroblastoma tumorigenesis is regulated through the Nm23-H1/h-Prune C-terminal interaction. Sci Rep 3, 1351 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01351

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01351

This article is cited by

-

Signature literature review reveals AHCY, DPYSL3, and NME1 as the most recurrent prognostic genes for neuroblastoma

BioData Mining (2023)

-

Knockdown of TRIM22 Relieves Oxygen–Glucose Deprivation/Reoxygenation-Induced Apoptosis and Inflammation Through Inhibition of NF-κB/NLRP3 Axis

Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology (2021)

-

A competitive cell-permeable peptide impairs Nme-1 (NDPK-A) and Prune-1 interaction: therapeutic applications in cancer

Laboratory Investigation (2018)

-

Oncogenic Epstein–Barr virus recruits Nm23-H1 to regulate chromatin modifiers

Laboratory Investigation (2018)

-

Correlation between NM23 protein overexpression and prognostic value and clinicopathologic features of ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.