Abstract

Use of a single template-grown carbon nanotube as a separation column to separate attoliter volumes of binary mixtures of fluorescent dyes has been demonstrated. The cylindrical nanotube walls are used as stationary phase and the surface area is increased by growing smaller multi-walled carbon nanotubes within the larger nanotube column. Liquid-liquid extraction is performed to separate selectively soluble solutes in a solvent and chromatographic separation is demonstrated using thin, long nanotubes coated inside with iron oxide nanoparticles. The setup is also used to determine the diffusion coefficient of a solute at the sub-micrometer scale. This study opens avenues for analytical chemistry in attoliter volumes of fluids for various applications and cellular analysis at the single cell level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Separation of minute quantities of liquid mixtures has attracted much attention due to its applications in analysis of hazardous, rare and bio chemicals. The scientific community has long realized the importance of sub-cellular and single cell analysis of DNA, RNA, proteins, amino acids and other biomolecules to better understand cell biochemistry and functioning1,2,3,4,5. Moreover a cell population of the same type exhibits heterogeneity6, due to which any study of cell colony provides only averaged data. Although some novel research tools were developed that had sufficient mechanical strength to overcome cellular resistance to penetration and their applications to intra-cellular experiments were recently demonstrated7,8,9,10, methods to selectively detect and quantify analytes in individual living cells have been lacking. This need has led to efforts in miniaturizing instrumentation for existing analytical techniques like gas, liquid, electro-chromatography, etc11. Much smaller columns and finer packing particles (stationary phase) have been employed in the recent past12,13,14,15,16. However these have either been fabricated by etching channels on microchips or are too large in overall diameter to be useful for cell piercing. Analyte separation in nanochannels by electrophoresis has also been pursued13,17,18, however those devices and techniques are either incompatible with, or lack the mechanical strength and flexibility to probe a single living cell.

Various carbon allotropes which exhibit a large surface area available for adsorption and can be chemically and physically functionalized are widely used in micro-separation techniques19,20,21,22,23. Herein, we demonstrate feasibility of using single carbon nanotubes (CNT) with the length of about 40 µm, 70 to 200 nm in outer diameter (O.D.) and 60 to 190 nm in inner diameter (I.D.) (Fig. S1) for separation of distinct chemical species. As an example, we present a setup for separation of fluorescent dyes, employing fluorescence confocal microscopy as the detection tool. Previously, the filling of similar CNTs (also called nanopipes) with various particulates and liquids and their use as conduits for fluid flow generated by Laplace pressure was demonstrated24,25. Consequently, cellular endoscopes were developed that utilized the exceptional physical properties of 50–200 nm diameter single CNT tips (Fig. S2), enabling them to easily and non-invasively pierce cell membranes and perform attoliter fluid injection and extraction from individual mammalian cells10. The ability to transport aqueous liquids and a strong interaction between the fluid and carbon tube walls have been previously shown26. However no separation or selective extraction of liquids using single CNTs has ever been reported. This work provides a conceptual basis for development of chromatographic columns based on single nanotubes and capable of extracting and analyzing attoliter volumes of liquids.

Results

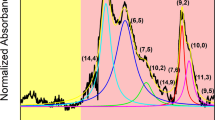

Diffusion rate based separation

A CNT was prefilled with pure diphenyl ether (DPE) by contacting one end of it with a small drop of DPE. A mixture of fluorescent green (BODIPY® 493/503, 0.69 mM) and fluorescent red (BODIPY® 650/665, 0.95 mM) dyes was prepared in DPE, a small drop of which was contacted with the other end of the CNT. This caused the two dyes to diffuse into the pure DPE drop through the CNT. After transporting through the CNT, we initially obtained a higher concentration of green dye in the pure DPE droplet as indicated schematically in Fig. 1(a). The ratio of the concentrations of the two dyes was calculated from the experimentally recorded fluorescence intensities (Fig. 1(b) and Methods Section) and plotted against time (Fig. 1(c)). We observed that the [green]/[red] dye concentration ratio starts at a very high value and drops to 1.6±0.9 (close to the calculated value of 1.31, Supplementary Information 1.4).

Diffusion based separation of a mixture of BODIPY® 493/503 and BODIPY® 650/665 in DPE through a 200 nm (O.D.), 190 nm (I.D.) CNT.

(a) Schematic showing molecular structures of the dyes and experimental layout. (b) Spectrally filtered fluorescence micrographs of (i) green, (ii) red dyes showing diffusion from solution to pure solvent (DPE) and regions of interest (ROIs) from which the average fluorescence intensity was recorded. Scale bar = 15 µm. (c) Ratio of green to red fluorescence intensities vs time for filled and plain CNTs shown in Fig. S1(a–b). Error bars represent standard deviation from average values (symbols).

To increase the CNT-dye interactions and enhance the separation, we employed CNTs with smaller multiwalled CNTs grown inside, an analog of column packing in traditional chromatography (Fig. S1(b) and Methods section)27,28. When a composite CNT (containing MWCNTs) was used, the intensity ratio increased from a very low initial value (close to zero) converging finally to an almost constant value (6±3), near that observed for the plain CNTs (Fig. 1(c)). This indicates a reversal of selectivity of the CNT column to the two dyes and is therefore, potentially a method to tune material transport through the tube and the composition of the extracted liquid by controlling the density of grown MWCNTs.

Liquid-liquid extraction

A solution of BODIPY® 493/503 (0.69 mM) and Nile Red (1.1 mM) was prepared in DPE in which both dyes are soluble. 1-octadecene (1-OD) was used to prefill the CNT and this caused only the green dye to diffuse into the 1-OD phase due to a low solubility of Nile Red in 1-OD (Fig. 2(a–b)). As can be seen from Fig. 2(b)(ii) and 2(c)(ii), negligible fluorescence intensity was recorded from the 1-OD phase in the yellow-orange (Nile Red) wavelength region compared to that recorded when DPE was used. Meanwhile, the intensity of green (BODIPY® 493/503) fluorescence recorded was similar no matter DPE or 1-OD was used (Fig. 2(b)(i) and 2(c)(i)).

Demonstration of liquid-liquid extraction.

(a) Schematic showing BODIPY® 493/503 being extracted from DPE, into 1-OD through a 190 nm (I.D.) and 200 nm (O.D.) nanotube. (b) (i) green and (ii) orange fluorescence micrographs, showing dye diffusion from solution (in DPE) to pure solvent (1-OD). Scale bar = 15 µm. (c) Comparison of concentrations vs time of (i) green and (ii) orange dye in the pure solvent droplet when the solvent is DPE or 1-OD.

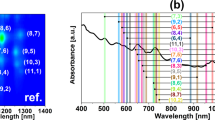

Estimation of diffusion coefficients

Since diffusion plays a major role in nano-separation processes analyzed in this study, we performed 3D finite element analysis of the problem using the Comsol Multiphysics (Comsol Inc.) software. The slope of the linear regions (initial 8–30 s) of the concentration-time curve calculated from the solvent droplet was computed for a range of diffusion coefficients (D = 0.3−1 ×10−5 cm2/s) and lengths (20–60 µm) of CNTs and is plotted in Fig. 3. For the slope of concentration-time curve in our experimental data (Fig. 2(c)(i)), the diffusion coefficient of BODIPY® 493/503 from Fig. 3 can be estimated to be approximately 0.88 ×10−5 cm2/s (Fig. S9 and Table S2 for diffusion data for other dyes). Alternatively, the diffusion coefficient can be estimated using the equation written for a diaphragm-cell29:

Calculated diffusion coefficient of a solute diffusing into a drop of pure DPE vs rate of change of concentration, where diffusion occurs through a 190 nm (I.D.) CNT of different lengths attainable using AAO template technology.

The diffusion coefficient of BODIPY® 493/503 was estimated for the experimentally obtained slope of concentration-time curve as shown in the plot by the dotted lines for 40 µm long CNTs.

where  assuming same volume (V) for the two hemispherical drops (diameter = 35 µm), A and L being the average values of cross sectional area (I.D. = 190 nm) and length (40 µm) of a nanotube, c1 and c2 are solute concentrations in the solution drop (0.69 mM) and in pure solvent drop (at time t), respectively. Using this equation, we obtain a value ∼0.9 ×10−5 cm2/s for the diffusion coefficient of BODIPY® 493/503 in DPE. A small difference in the values of diffusion coefficients obtained using these two methods arises from variable CNT length, slight difference in cross-sectional area, drop sizes and the inability of either method to take into account the effect of the carbon walls on separation. However, the values produced by both methods agree closely with each other.

assuming same volume (V) for the two hemispherical drops (diameter = 35 µm), A and L being the average values of cross sectional area (I.D. = 190 nm) and length (40 µm) of a nanotube, c1 and c2 are solute concentrations in the solution drop (0.69 mM) and in pure solvent drop (at time t), respectively. Using this equation, we obtain a value ∼0.9 ×10−5 cm2/s for the diffusion coefficient of BODIPY® 493/503 in DPE. A small difference in the values of diffusion coefficients obtained using these two methods arises from variable CNT length, slight difference in cross-sectional area, drop sizes and the inability of either method to take into account the effect of the carbon walls on separation. However, the values produced by both methods agree closely with each other.

Frontal Chromatography

To demonstrate frontal chromatography, a mixture of BODIPY® 493/503 (green) and BODIPY® 650/665 (red) (0.5 mM each) was prepared in mineral oil. A drop of this mixture was drawn and contacted with one end of a ∼70 nm O.D. and ∼60 nm I.D. CNT (as depicted in Fig. 4(a)) placed on a silanized glass coverslip. The CNT was filled by capillary action within 5 seconds and it was observed that only the green front progressed to fill the entire CNT length (Fig. 4(b)(i)). A small red front starts to proceed but halts when the CNT gets fully filled and capillary flow ceases (Fig. 4(b)(ii)). The red front is then seen to propagate slowly (Fig. S6(a–b)) due to diffusion as shown in the plot in Fig. 4(c). When DPE was used instead of oil (Fig. S7(a–b)), distinct green and red fronts still appeared, but the higher diffusion rate of red dye caused the red front to catch up with the green front at the CNT end in about a minute. We also attempted separation of BODIPY® 493/503 and Nile Red using this technique but were unable to capture visual evidence of separation as both green and red fronts seemed to nearly coincide, probably owing to lesser difference in molecular structures and interactions of the two dyes with the CNT walls (Fig. S7(c–d)). When the inner surface of CNTs was coated with iron oxide nanoparticles30 (Fig. S1 (d)) thereby closely resembling conventional packed chromatography columns and were used to separate the dye mixture flowing by capillary action (as aforementioned), we observed slower movement of the red front compared to that observed using plain CNTs (Fig. 4(c)). Fig. 4(d) shows a setup for collecting one pure component from the leading front in a CNT column, with high resolution. In this case, a ∼70 nm O.D. and ∼60 nm I.D. CNT is used as the separation column and a larger drop of pure solvent is contacted with the other end of the CNT, once it has entirely been filled by capillary flow from the smaller solution drop. That will ensure continuity of flow due to Laplace pressure difference even after capillary flow ceases25. The inset in Fig. 4(d) shows an enhanced (using ImageJ software) image of BODIPY® 493/503 transferred into a drop of mineral oil placed on silanized glass after 10 minutes of commencement of flow.

Separation driven by capillary flow in a ∼70 nm O.D. and ∼60 nm I.D. CNT.

(a) Schematic representing formation of green and red fronts on capillary filling. (b) Spectrally resolved micrographs of (i) green and (ii) red fluorescent dyes providing an experimental evidence of separation of green dye from red dye in the leading front (frontal chromatography). Scale bar = 20 µm. (c) Plot of subsequent propagation of red front due to diffusion, vs time. Propagation rates for plain (empty) CNTs compared with those for CNTs coated with iron oxide nanoparticles (Fig. S1(d)). Smooth quadratic curves were fitted to depict diffusive movement of the red dye for plain CNTs (dashed curve) and for CNTs coated with iron oxide nanoparticles (solid curve). (d) Setup for collecting pure component from the leading front in a pure solvent drop, while using 70 nm O.D. and 60 nm I.D. CNTs. Scale bar = 40 µm. Inset shows fluorescent image of transported green dye.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate separation of analytes in attoliter volumes using a single CNT. We utilized fluorescent dyes as analytes and fluorescence microscopy for detection owing to high sensitivity of the technique and small volumes, transport rates and length scales involved in the experiments. We employed DPE, which is a non-polar solvent that has a high solubility for the dyes and easily wets the CNTs. We covered the drops of non-polar solvents and the nanotube between them with a larger water drop to suppress heat induced evaporation. High polarity of water prevents wetting of the outer nanotube surface by DPE and causes the DPE drop to assume a non-wetting (contact angle >90°) shape minimizing energetically unfavorable surface interactions. Thus, when two drops are connected to two ends of a CNT, fluid transport from one drop to the other occurs exclusively through the CNT channel. However, using this set of liquids does not prevent outer surface wetting when graphitic CNTs are used (Fig. S4), probably because of enhanced favorable interactions between graphitic walls of CNTs and non-polar organic solvents. Meanwhile polar and hydrophilic solvents can also be used for separation by modifying the setup as explained in Supplementary Information section 1.6, however we persisted with non-polar solvents in this study as they provide a convenient means for demonstrating the concept. Our setup (explained in the methods section) overcomes two key issues critical for success of experiments involving femto-liter (or smaller) samples: rapid evaporation of liquids with moderate to high vapor pressures at ambient conditions and the outer surface wetting of the CNT. When two drops (that of pure DPE and dye mixture) are contacted with the two ends of a CNT, a Laplace pressure difference may generate fluid flow25 between the drops owing to small uncontrollable variations in the sizes and shapes of the drops. However this pressure gradient is insignificant in our experiments and its direction varies in individual trials, dampening out the variance with an increased number of experiments. Furthermore, we did not observe any change in the droplet size over the course of any experiment, suggesting that fluid flow was negligible.

Both fluorescent dyes (green and red) are soluble in DPE but are transported through the CNT channel at different rates corresponding to their diffusion coefficients and interactions with CNT walls. This initially results in a high ([green]/[red]) concentration ratio (Fig. 1 (c)) recorded from the pure DPE drop owing to the high diffusion coefficient (as shown later) and lower retention of the green dye by the CNT walls. The concentration ratio then decays to the equilibrium value of 1.6±0.9 and the relative transport is solely determined by relative diffusion rates due to the occupation of all active sites on the inner CNT surface by dye molecules.

To increase the CNT-dye interactions and enhance the separation, the CNT's internal surface area should be increased, which can be achieved by packing the tube with nanoparticles. However we have not yet been able to achieve a liquid flow rate desirable for fluorescence detection through a tube packed with iron oxide or diamond nanoparticles30. Therefore we used CNTs with smaller multiwalled CNTs grown inside (Fig. S1(b) and Supplementary Information 1.2)27,28. The altered initial part of the [green]/[red] vs time curve observed in Fig. 1(c) can be attributed to the interaction of the inner MWCNTs with the dye molecules. In this case, as suggested by our experimental data, the interaction with the green dye molecules is stronger than with the red dye molecules, resulting in an initial retention of the green dye. In all cases, we expect the eventual [Green]/[Red] value in the pure solvent drop to converge to ∼0.7, equaling that in the original solution if the experiment is allowed to run for sufficiently long times.

Liquid-liquid extraction was demonstrated by employing a pure solvent that selectively dissolves one solute as schematically represented in Fig. 2 (a). Thus when pure 1-OD is used as a solvent to prefill the CNT and a mixture of the green dye and Nile Red in DPE is contacted at the other end, the green dye (which is soluble in both solvents) can be selectively extracted into 1-OD phase, leaving behind Nile Red (which is weakly soluble in 1-OD) in the DPE phase (Fig. 2(b)). Indeed, similar transfer rates of the green dye were recorded from both pure DPE or 1-OD droplet (Fig. 2 (c)(i)) while negligible Nile Red transport was detected in 1-OD compared to that in DPE (Fig. 2(c)(ii)).

Owing to uncertainty in the operating temperature and viscosity due to intermittent laser exposure, we modeled the diffusion process using a finite element method software. The initial slope of the concentration-time curves has been calculated as a function of diffusion coefficient of the solute and CNT length using finite element analysis and plotted in Fig. 3 using which diffusion coefficients of solutes in solvents can be determined under experimental conditions used in our study. Further, Fig. 3 can assist in selecting the CNT length for separation of molecules with different diffusion coefficients. Depending on the minimal detectable concentration change of the analyzed compound, different tube lengths may be needed. A longer and thinner nanotube is favorable for better separation due to higher aspect ratio31,32, however it will also reduce the flow rate due to a higher viscous force making it hard to detect at low concentrations. CNTs used in this study so far were 190 nm in I.D. to enable easier and more accurate detection. However, tubes with diameters down to 10 nm can be produced by the template-assisted growth in anodized aluminum oxide (AAO) membranes.

The diaphragm-cell model, which was developed for diffusive transport across a uniformly thick diaphragm, is also useful in determining diffusion coefficients of solutes used in our setup. While the model ignores tortuosity of the diaphragm pores and convective transport due to buoyancy, the CNTs in our studies are synthesized as straight and uniform channels and tortuosity is no longer an issue. Further, buoyancy effects are negligible at the length scale of our experimental setup. Moreover, as shown in FEA simulations in Fig. S5, the concentration profile across the length of a nanotube becomes linear in less than 10 seconds even for a low diffusion coefficient solute. Therefore the diaphragm-cell model (which also assumes a linear concentration profile) is expected to provide results with high accuracy for our experiments. As can be seen in Table S2, the results obtained from both FEA simulations and the diaphragm-cell model closely match each other.

The observation of clearly separated green and red fronts inside the CNT (Fig. 4 (b)) during capillary filling further establishes the important point that the CNT walls interact differently with distinct chemical species, indicating that CNTs can be used as a chromatographic column. In these experiments we used mineral oil as the mobile phase since the diffusion of the red dye in the oil is slow (taking more than 90 minutes) and easier to record due to a higher oil viscosity. Further, it is not required to submerge the system in water owing to negligible evaporative loss of mineral oil (low vapor pressure as shown in Table S1). Several methods to functionalize CNTs have been developed in the past, which makes individual CNTs highly versatile for performing chromatographic separation. In the present work, we coated the CNTs with paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles30 and examined capillary filling of the dye mixture. Herein we observed the propagation speed of the red front to be much slower than through empty CNTs (Fig. 4c). This reduced propagation speed must be due to interactions between the diffusing red dye molecules and the iron oxide nano-particles, since the CNT column gets filled by capillary action within seconds, leaving diffusion to be the only mechanism for further movement of red dye through the CNT column. Therefore we fitted the two sets of data points (plain CNTs and Iron Oxide coated CNTs) with quadratic curves which are typical of diffusive transport and a close fit was observed.

In the separation techniques presented, the ability to detect a small number of transported molecules will be the limiting factor rather than CNT diameter, while attempting to push the limits of the techniques to smaller length scales or in employing more dilute solutions. Surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) or electrochemical detection may prove beneficial in these applications as SERS allows single molecule sensitivity33 and electrochemical detection is routinely used to study transport of single protein molecules through nanoholes34. We used individual CNTs on a substrate for demonstration purposes. For developing functional CNT-based chromatographic columns, these tubes can be assembled into nanofluidic devices35 or used as nanopipette tips10 allowing separation and analysis of attoliters of fluids in forensics, nanoanalytical chemistry and single-cell analysis.

Overall, miniaturization of separation processes is highly desirable, but comes with many challenges. In this study we developed a method to overcome sample evaporation and eliminate wetting issues to perform attoliter volume separation in liquid phase. We showed that the experimental setup utilizing single (190 nm I.D., 200 nm O.D.) nanotube (nanopipe) could be used to measure diffusion coefficients of solutes on small length scales. The walls of an individual carbon nanotube could be chemically functionalized and used as stationary phase in liquid phase separation. Separation of two fluorescent dyes with non-overlapping excitation and emission wavelengths was demonstrated. The selectivity of separation could be controlled by packing the nanotubes with nanopartcles and we demonstrated this by growing multi-walled CNTs inside a larger CNT and by coating CNTs with iron oxide nanoparticles. CNTs can also be packed with nanoparticles to create nanoscale packed chromatographic columns24,30. Further, by using a solvent that selectively dissolves one dye, we demonstrated the process of liquid-liquid extraction. Thus we were successful in demonstrating various separation techniques with the smallest individual separation column ever reported, which holds great promise for minimally-invasive single cell analysis.

Methods

CNT column fabrication

Carbon was deposited by chemical vapor deposition (CVD) from an ethylene-argon mixture at 670°C inside channels of anodic alumina membranes (60–150 µm thick, 70–200 nm I.D.) as described elsewhere36. In a modified fabrication method27,28, the alumina membranes were impregnated with a 0.5 M solution of Ni(NO3)2·6H2O for a day, followed by calcination for an hour at 300°C and reduction in hydrogen at 400°C. This results in formation of metallic nickel nano-particles on pore walls of the membrane. When CVD was performed on these membranes, it resulted in amorphous 200 nm outer diameter CNTs having smaller ∼20 nm multi-walled CNTs within them. To coat the CNTs with iron oxide nano-particles (∼10 nm in diameter), the carbon coated alumina membranes were impregnated with oil based ferro fluid (EMG 911, Ferro Tec Corp.) and dried in an oven at 80°C for 24 hours30. The alumina matrix was subsequently dissolved in aqueous 1M NaOH solution for 5 hours at 90°C to release the CNTs. The suspension was neutralized by rinsing with deionized water and then filtered. Finally a suspension in ethanol was prepared for further use (Fig. S1).

Experimental procedure

The setup for performing separation consists of a cleaned glass micro coverslip on which a drop of the aforementioned CNT suspension was released. The ethanol from the suspension was allowed to evaporate in an oven at 50°C leaving the CNTs adhered to the glass surface due to van der Waals forces. The coverslip was positioned above the confocal microscope objective. A large drop of deionized water was then placed on the coverslip to immerse all CNTs, which helped dissipate the heat generated by exposure to laser. Borosilicate glass capillary was pulled into a micropipette using a commercial glass pipette puller (P1000, Sutter Instruments) and filled with the dye solution. It was connected to a pressure injection device (FemtoJet®, Eppendorf) and held by a nanomanipulator (Eppendorf) bound to a fluorescence confocal microscope (Olympus FluoViewTM FV1000). Drops of DPE (pure and containing dye mixture) were extracted at the site of the CNT ends by applying a suitable pressure with FemtoJet® (Fig. S3).

Fluorescence detection

The red and green fluorescent dyes used in our experiments have non-overlapping excitation/emission frequency bands. This enables us to filter the green fluorescent signal from red using suitable wavelength filter cubes and detect the dyes "individually". The confocal microscope was operated in sequential frame mode, which allows the column to be exposed to the laser (488 nm for BODIPY® 493/503, 543 nm for Nile Red and, 635 nm for BODIPY® 650/665) of one wavelength at a time. Suitable filter cubes (505–525 nm for green, 560–620 nm for yellow-orange and 655–755 nm for red) for resolving the fluorescence signal into green, yellow-orange and red components were employed and the output intensities were recorded with time. To minimize photobleaching effects, the shutter of the confocal microscope was opened for laser exposure only for short time intervals (20 seconds in the beginning, followed by periodic 30 second closure and 15 second opening).

A droplet of pure solvent was placed next to the CNT as a reference for recording the background fluorescence intensity (Fig. S3). This was subtracted from the intensity recorded from the pure solvent drop placed at one CNT end to negate the effect of auto fluorescence of solvents used. Meanwhile we always tried to draw droplets of same size to minimize the Laplace pressure drop along the length of the CNT. Therefore we assumed any dye transfer between the drops to be entirely due to diffusion.

Concentration calibration

A known amount of each dye was dissolved in a known amount of DPE. A drop of this solution was placed under the confocal microscope and the fluorescence intensity was recorded. This procedure was repeated while successively diluting the dye solution two folds. The data obtained was used to find the intensity-concentration correlation for each dye and the best fit linear function was determined. All confocal microscope parameters (such as detector voltage, laser power etc.) were fixed in these and all other experiments in this study. The calibration curves for each dye were obtained by this method and have been used throughout the manuscript for calculating concentrations from fluorescence intensities:

[BODIPY® 493/503] = (88.38×Intensity – 100) nM

[BODIPY® 650/665] = (250×Intensity – 75) nM

[Nile Red] = (42×Intensity + 200) nM

References

Leslie, M. The Power of One. Science 331, 24–26 (2011).

Holland, L. A. & McKeon, J. Miniaturized liquid separation techniques in bioanalysis. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 378, 40–42 (2004).

Kennedy, R., Oates, M., Cooper, B., Nickerson, B. & Jorgenson, J. Microcolumn separations and the analysis of single cells. Science 246, 57–63 (1989).

Ewing, A. G. Microcolumn Separations of Single Nerve-Cell Components. J. Neurosci. Methods 48, 215–224 (1993).

Li, L., Golding, R. E. & Whittal, R. M. Analysis of Single Mammalian Cell Lysates by Mass Spectrometry. Journal of the American Chemical Society 118, 11662–11663 (1996).

Kennedy, R. T. & Jorgenson, J. W. Quantitative analysis of individual neurons by open tubular liquid chromatography with voltammetric detection. Analytical Chemistry 61, 436–441 (1989).

Han, S., Nakamura, C., Obataya, I., Nakamura, N. & Miyake, J. Gene expression using an ultrathin needle enabling accurate displacement and low invasiveness. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 332, 633–639 (2005).

Obataya, I., Nakamura, C., Han, Nakamura, N. & Miyake, J. Nanoscale Operation of a Living Cell Using an Atomic Force Microscope with a Nanoneedle. Nano Letters 5, 27–30 (2004).

Schrlau, M. G., Dun, N. J. & Bau, H. H. Cell Electrophysiology with Carbon Nanopipettes. ACS Nano 3, 563–568 (2009).

Singhal, R. et al. Multifunctional carbon-nanotube cellular endoscopes. Nature Nanotechnology 6, 57–64 (2011).

Dovichi, N. J. & Zhang, J. Z. How capillary electrophoresis sequenced the human genome. Angew. Chem.-Int. Edit. 39, 4463–4468 (2000).

Kato, M. et al. Femto Liquid Chromatography with Attoliter Sample Separation in the Extended Nanospace Channel. Analytical Chemistry 82, 543–547 (2009).

Wang, X., Kang, J., Wang, S., Lu, J. J. & Liu, S. Chromatographic separations in a nanocapillary under pressure-driven conditions. Journal of Chromatography A 1200, 108–113 (2008).

Detobel, F. et al. Estimation of surface desorption times in hydrophobically coated nanochannels and their effect on shear-driven and pressure-driven chromatography. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 394, 399–411 (2009).

Malkin, D. S., Wei, B., Fogiel, A. J., Staats, S. L. & Wirth, M. J. Submicrometer Plate Heights for Capillaries Packed with Silica Colloidal Crystals. Analytical Chemistry 82, 2175–2177 (2010).

Taylor, L. C., Lavrik, N. V. & Sepaniak, M. J. High-Aspect-Ratio, Silicon Oxide-Enclosed Pillar Structures in Microfluidic Liquid Chromatography. Analytical Chemistry 82, 9549–9556 (2010).

Garcia, A. L. et al. Electrokinetic molecular separation in nanoscale fluidic channels. Lab on a Chip 5, 1271–1276 (2005).

Yu, S. F., Lee, S. B. & Martin, C. R. Electrophoretic protein transport in gold nanotube membranes. Analytical Chemistry 75, 1239–1244 (2003).

Halasz, I. & Horvath, C. Thin-Layer Graphited Carbon Black as Stationary Phase for Capillary Columns in Gas Chromatography. Nature 197, 71–& (1963).

Knox, J. H., Unger, K. K. & Mueller, H. Prospects for Carbon ss Packing Material in High-Performance Liquid-Chromatography. J. Liq. Chromatogr. 6, 1–36 (1983).

Fonverne, A. et al. In situ synthesized carbon nanotubes as a new nanostructured stationary phase for microfabricated liquid chromatographic column. Sensors and Actuators B-Chemical 129, 510–517 (2008).

Nesterenko, P. N. & Haddad, P. R. Diamond-related materials as potential new media in separation science. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 396, 205–211 (2010).

Sae-Khow, O. & Mitra, S. Carbon nanotubes as the sorbent for integrating [mu]-solid phase extraction within the needle of a syringe. Journal of Chromatography A 1216, 2270–2274 (2009).

Kim, B. M., Qian, S. & Bau, H. H. Filling Carbon Nanotubes with Particles. Nano Letters 5, 873–878 (2005).

Sinha, S., Rossi, M. P., Mattia, D., Gogotsi, Y. & Bau, H. H. Induction and measurement of minute flow rates through nanopipes. Physics of Fluids 19, 013603 (2007).

Megaridis, C. M., Yazicioglu, A. G., Libera, J. A. & Gogotsi, Y. Attoliter fluid experiments in individual closed-end carbon nanotubes: Liquid film and fluid interface dynamics. Physics of Fluids 14, L5–L8 (2002).

Che, G. L., Lakshmi, B. B., Fisher, E. R. & Martin, C. R. Carbon nanotubule membranes for electrochemical energy storage and production. Nature 393, 346–349 (1998).

Mattia, D., Korneva, G., Sabur, A., Friedman, G. & Gogotsi, Y. Multifunctional carbon nanotubes with nanoparticles embedded in their walls. Nanotechnology 18, 155305 (2007).

Cussler, E. L. Diffusion: Mass Transfer in Fluid Systems. 2nd edn, (Cambridge University Press, 1984).

Korneva, G. et al. Carbon nanotubes loaded with magnetic particles. Nano Letters 5, 879–884 (2005).

Wang, X. et al. Nanocapillaries for Open Tubular Chromatographic Separations of Proteins in Femtoliter to Picoliter Samples. Analytical Chemistry 81, 7428–7435 (2009).

Han, S. et al. Chromatography in a Single Metal−Organic Framework (MOF) Crystal. Journal of the American Chemical Society 132, 16358–16361 (2010).

Kneipp, K. et al. Single molecule detection using surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS). Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1667–1670 (1997).

Han, A. et al. Label-free detection of single protein molecules and protein-protein interactions using synthetic nanopores. Analytical Chemistry 80, 4651–4658 (2008).

Riegelman, M., Liu, H. & Bau, H. H. Controlled Nanoassembly and Construction of Nanofluidic Devices. Journal of Fluids Engineering 128, 6–13 (2006).

Mattia, D. et al. Effect of graphitization on the wettability and electrical conductivity of CVD-carbon nanotubes and films. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 110, 9850–9855 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from W.M. Keck Foundation to establish Keck Institute for Attofluidic Nanotube-based Probes at Drexel University and NSF NIRT grant CTS-0609062. We would like to thank Dr. Junjie Niu and Ms. Olha Mashtalir for help with TEM imaging performed at the Centralized Research Facility of the College of Engineering, Drexel University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.G. supervised the project. Y.G., G.F., V.M. conceptualized the technique. R.S. designed and performed all experiments. M.L. synthesized all alumina membranes. R.S., M.L. and V.M. analyzed the data. All authors were involved in writing the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Separation and Liquid Chromatography Using a Single Carbon Nanotube

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareALike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Singhal, R., Mochalin, V., Lukatskaya, M. et al. Separation and liquid chromatography using a single carbon nanotube. Sci Rep 2, 510 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00510

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00510

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.