Abstract

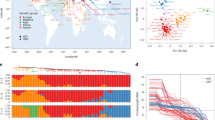

Plant genomes, and eukaryotic genomes in general, are typically repetitive, polyploid and heterozygous, which complicates genome assembly1. The short read lengths of early Sanger and current next-generation sequencing platforms hinder assembly through complex repeat regions, and many draft and reference genomes are fragmented, lacking skewed GC and repetitive intergenic sequences, which are gaining importance due to projects like the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE)2. Here we report the whole-genome sequencing and assembly of the desiccation-tolerant grass Oropetium thomaeum. Using only single-molecule real-time sequencing, which generates long (>16 kilobases) reads with random errors, we assembled 99% (244 megabases) of the Oropetium genome into 625 contigs with an N50 length of 2.4 megabases. Oropetium is an example of a ‘near-complete’ draft genome which includes gapless coverage over gene space as well as intergenic sequences such as centromeres, telomeres, transposable elements and rRNA clusters that are typically unassembled in draft genomes. Oropetium has 28,466 protein-coding genes and 43% repeat sequences, yet with 30% more compact euchromatic regions it is the smallest known grass genome. The Oropetium genome demonstrates the utility of single-molecule real-time sequencing for assembling high-quality plant and other eukaryotic genomes, and serves as a valuable resource for the plant comparative genomics community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The genomes of Arabidopsis3, rice4, poplar, grape and Sorghum5 were first sequenced using high-quality and reiterative Sanger-based approaches producing a series of ‘gold standard’ reference genomes. The advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies reduced costs of sequencing substantially, which has enabled sequencing of over 100 plant genomes1. The quality of plant genome assemblies depends on genome size, ploidy, heterozygosity and sequence coverage, but most NGS-based genomes have on the order of tens of thousands of short contigs distributed in thousands of scaffolds. The short read lengths of NGS, inherent biases and non-random sequencing errors have resulted in highly fragmented draft genome assemblies that are not complete, which means they are missing biologically meaningful sequences including entire genes, regulatory regions, transposable elements, centromeres, telomeres and haplotype-specific structural variations. It is becoming clear from ENCODE projects that complete genomes are needed to better understand the importance of the non-coding regions of genomes2.

More than 40% of calories consumed by humans are derived from grasses, and the grass family (Poaceae) is arguably the most important plant family with regard to global food security6. The size and complexity of most grass genomes has challenged progress in gene discovery and comparative genomics, although draft genomes are now available for most agriculturally important grasses1. The largest genome assemblies, such as maize (2,300 megabases (Mb))7, barley (5,100 Mb)8 and wheat (hexaploid, 17,000 Mb)9 are highly fragmented as a result of the inability of current sequencing technologies to span complex repeat regions. Near-finished reference genomes are available for rice4, Sorghum5 and Brachypodium10, but more high-quality grass genomes are needed for comparative genomics and gene discovery. Here we present the ‘near-complete’ draft genome of the grass Oropetium thomaeum, the first high-quality reference genome from the Chloridoideae subfamily. The draft genome is near complete because we were able to sequence through complex repeat regions that are unassembled in most draft genomes. Oropetium has the smallest known grass genome at 245 Mb and is also a resurrection plant that can survive the extreme water stress such as loss of >95% of cellular water (Fig. 1)11.

a, Well watered. b, Desiccated (relative water content <5%) after 9 days of drought stress. c, Condition 24 h post-hydration (relative water content >70%).

Single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing (Pacific Biosciences) produces long and unbiased sequences, which enables assembly of complex repeat structures and GC- and AT-rich regions that are often unassembled or highly fragmented in NGS-based draft genomes. We generated ~72× sequencing coverage of the Oropetium genome using 32 SMRT cells on the PacBio RS II platform (which is equivalent to <1 week of sequencing time and <US$10,000 in reagents). The resulting sequence had a read N50 length of over 16 kilobases (kb), and there was 10× coverage of reads over 20 kb in length (Extended Data Fig. 1a). The raw reads were error-corrected using the hierarchical genome assembly process (HGAP), and the longest reads (>16 kb) were assembled using Celera assembler followed by two rounds of genome polishing using Quiver12. The assembly contains 650 contigs spanning 99% (244 Mb) of the estimated 245 Mb genome size (Extended Data Fig. 1b) with a contig N50 length of 2.4 Mb (Extended Data Fig. 1c). The final assembly consists of 625 contigs after removal of the complete chloroplast genome, mitochondria-derived contigs and contaminants. The 35 largest contigs span half the genome, and the largest 107 contigs contain 90% of the sequence. The 135,324 base-pair (bp) chloroplast genome assembled into a single contig that includes both ~25 kb of inverted repeat regions which typically collapse into a single copy during assembly. The mitochondria genome was assembled into 20 partially overlapping circular chromosomes, which are the product of intramolecular recombination events that collectively span 1,100 kb.

The Oropetium genome has high contiguity for an uncurated draft plant genome. The average contig N50 length for all published plant genomes is 50 kb compared to 2.4 Mb for Oropetium (Extended Data Fig. 1d, e). After manual curation and data augmentation, only the Arabidopsis (TAIR10)13, rice (V7) and Brachypodium (V 2.1)10 genomes have longer contig N50 lengths. The accuracy rate is very high at 99.99995%, which is similar to Sanger-based approaches and higher than most NGS-based assemblies (Extended Data Fig. 1h). We plotted repeat density and GC content along the length of the contigs to identify factors causing contig breaks (Extended Data Fig. 1f, g). There is no correlation between repeat density and GC content at contig break points. This suggests that contig break points occur at the start of repeats or that most assembly breaks are caused by other factors, such as within-genome heterozygosity or haplotype-specific structural variation. To test this, we also tried ‘diploid-aware’ assemblers Falcon (https://github.com/PacificBiosciences/falcon) and MinHash Alignment Process (MHAP)14. These assemblies had similar metrics but were less contiguous overall (Extended Data Fig. 1i).

The completeness of the Oropetium genome allowed us to accurately survey its highly repetitive features that are often unassembled in most plant genomes. The Oropetium assembly captures all 18 telomeric arrays (Extended Data Table 1) with repeat number ranging from 40 to 900, suggesting that at least some are full length. Three of the nine centromeric satellites are completely assembled into large inverted repeats spanning 400 kb with a base monomer length of 155 bp, and higher order structures of dimers (310 bp), trimers (465 bp) and tetramers (620 bp; Fig. 2, Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1). The remaining 40 centromeric sequences are incomplete centromere repeat fragments broken during assembly or solo repeats not associated with a larger centromere satellite. Nucleolus organizer regions contain tandem arrays of the 18S, 5.8S and 25S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes and typically span several megabase pairs with hundreds of nearly identical 10-kb arrays. Twenty-two full-length rRNA tandem arrays in six contigs are found in the Oropetium assembly (Extended Data Table 2). The largest tandem array contains five identical and one partial 9-kb repeats collectively spanning 51 kb; this is approaching the theoretical limit given the read-length distributions of our data. The remaining rRNA tandem repeats probably collapsed during read correction or genome assembly given their high sequence conservation.

The distributions of centromere-specific satellite DNA (CenOt), long terminal repeat retrotransposons (LTRs), DNA transposable elements (DNA-TE) and coding DNA sequences (CDS) are plotted. a, The gap-free assembly of a full-length centromeric array and the flanking highly repetitive pericentromeric region. b, The largest contig (7.8 Mb), which has a more typical distribution of elements.

Most repeats are incomplete, unassembled or highly collapsed in Illumina/454 NGS-based genomes, which has led to an underestimation and misclassification of repeat content in most plant genomes. Repetitive elements account for a surprisingly high proportion of the Oropetium genome (43%) compared to 21% in Brachypodium10, 35% in rice4, 54% in Sorghum5 and over 90% in wheat9 (Extended Data Table 3). Similar to these other genomes, the long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons are the most abundant class and account for 35.6% of the Oropetium genome. We identified 3,247 intact LTRs in 358 families, which is similar to rice (3,663) and Brachypodium (2,162), but far less than Sorghum (17,022)15. Only ~2% of the repeats are unclassified, which reflects the completeness of individual repeat elements due to the long reads.

Genome size in the grasses varies by several orders of magnitude as a consequence of polyploidy and genome bloating due to repetitive DNA accumulation16. Oropetium has the smallest known genome among the grasses17 at 90%, 60%, 50%, 30% and 10% the size of Brachypodium10, rice4, Setaria18, Sorghum5 and maize7, respectively. We found that Oropetium has a solo:intact LTR ratio >1, which is similar to small grass genomes like rice and Brachypodium, where proliferating LTRs are removed by illegitimate recombination, whereas large grass genomes like Sorghum and maize have solo:intact LTR ratios <1 (ref. 15). Despite its compact size, the Oropetium genome has a typical number of predicted protein coding genes at 28,446. A pan-cereal whole-genome duplication (WGD) event, called rho, occurred before the diversification of grasses5,19. There appear to have been no further WGDs in the selected grass genomes, including Oropetium, since the shared rho event4,5.

Genome alignments between Oropetium and selected grass genomes are mostly one-to-one after exclusion of the alignments derived from the shared genome duplication events (Extended Data Fig. 3a–e). Overall, 75% of the Oropetium genome, or 89% of its gene space, is contained in conserved syntenic blocks when compared to other grasses. Genomic colinearity across grass genomes is extensive, with a high density of orthologous genes spanning much of the euchromatin (Fig. 3). Insertions of retrotransposons and non-collinear genes that originated elsewhere in the genome contribute greatly to the differences in the intergenic sequences in grasses20.

Oropetium, part of the PACMAD clade, provides the first high-quality reference genome from the Chloridoideae subfamily—a large and diverse group of ~1,600 species that contains the orphan crops tef (Eragrostis tef) and finger millet (Eleusine coracana). Typical micro-colinearity patterns among genomic regions from Oropetium, Setaria, Sorghum, Oryza and Brachypodium are shown. Rectangles show predicted gene models, and colours indicate relative orientations. Matching gene pairs are displayed as grey connections. chr, chromosome.

The relative sizes of syntenic blocks in the grass genomes track closely with the overall genome size difference (Extended Data Fig. 3f). In contrast, the genomic span of coding sequences is similar across genes that are retained in orthologous locations, although coding features are slightly smaller in Oropetium (Extended Data Table 4). The relatively constant sizes of coding sequences among grass genomes confirm that genome size differences are indeed due to variations in the intergenic contents. It was thought that plants have a ‘one-way ticket to genome obesity’ due to the retention of proliferating transposable elements21. However, analysis of carnivorous plants Utricularia gibba (bladderwort, 82 Mb)22 and Genlisea aurea (corkscrew, 63.6 Mb)23 provided evidence that almost all intergenic space can be purged. Small genomes also arise from a reduction in gene number as seen in the aquatic monocotyledon Spirodela polyrhiza, which has the fewest predicted protein coding genes at 19,623 (ref. 24). Oropetium seems to have reduced both its intergenic and intragenic sequence.

As the intergenic sequence in Oropetium is specifically reduced compared with other grasses (Extended Data Fig. 3f), we determined which sequence accounted for its smaller genome size by comparing highly syntenic regions of the larger 730 Mb Sorghum genome. To identify highly orthologous regions we looked for Sorghum genes (promoter, 5′UTR, exons, introns and 3′UTR) with an increased number of conserved noncoding sequences25. We then analysed the top 48 Sorghum genes against their orthologous sequences in Oropetium and found that they were 38% (±0.27, 1 s.d.) larger in Sorghum (Extended Data Fig. 4a). The primary driver of gene-space expansion was highly unique ~1-kb intragenic sequences evenly spaced within the Sorghum genes. One explanation is that these evenly spaced highly unique sequences are degenerate remnants of transposons that have been partly purged from the Sorghum genome. Oropetium has a >1 solo:intact LTR ratio, consistent with active purging of transposons and complete loss of these regions. These results lend support to an emerging theory about the C-value paradox called the Genome Balance Hypothesis26, which suggests that selection on gene networks and pericentromeric growth (centromere movement) is balanced by transposon proliferation and retention. Therefore, these evenly spaced highly unique sequences balance the 6:1 expansion of pericentromeric sequence in Sorghum as compared to Oropetium (Extended Data Fig. 4b).

Desiccation tolerance was a key adaptation that permitted the most recent common ancestor of terrestrial plants to survive on land. Desiccation tolerance is widespread in bryophytes and lichens but rare in flowering plants, although similar mechanisms have evolved in vascular plants for seed and pollen desiccation. Desiccation tolerance to survive prolonged drought evolved independently in diverse monocotyledon and eudicotyledon lineages, and is found in at least 300 species. Gene duplications have provided the raw material for evolutionary innovation across plants. Tandem duplicated genes are often involved in stress responses and are probably important for adaptive evolution in dynamically changing environments. Oropetium has 6,668 tandem duplicated genes in 2,326 clusters, which is a slightly higher number than in other grasses, but a similar proportion (24% of genes). Tandem duplicated genes are enriched for gene ontology terms involved in response to abiotic stresses, gene regulation and cellular metabolism (Supplementary Table 2). In addition, Oropetium has 4,209 homeologous gene pairs retained from the rho WGD event, which are enriched for gene ontology terms related to gene regulation and stress responses such as transcription factor activity, nitrogen metabolism, response to abiotic stimulus, to salt stress and to oxygen-containing compounds (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). Understanding the genomic mechanisms of extreme desiccation tolerance in resurrection plants such as Oropetium may provide targets for engineering drought and stress tolerance in crop plants.

Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) SMRT sequencing has been used to close gaps in the human genome27, assemble complete bacterial genomes12 and identify novel gene isoforms28. Here we present a several hundred megabase plant genome, sequenced and assembled entirely by SMRT sequencing. The long SMRT reads produced a near-complete draft genome that captured three of nine complete centromeres, all of the telomeres and biologically relevant features of the Oropetium genome. The total time from extracted DNA to a complete assembly was less than one month, and costs for PacBio were comparable to an Illumina-based genome assembly. Our study demonstrates that SMRT sequencing enables a new level of genome assembly required for full ENCODE-type analysis of intergenic sequence, which is not currently possible with other NGS-based methods. The compactness of the Oropetium genome results from purging of both inter- and intragenic sequences, probably through small deletions during illegitimate recombination, as has been shown in other grasses. One hypothesis is that genome size is a function of cell size29, and consistent with this, all small plant genomes sequenced to date including Arabidopsis (125 Mb), Brachypodium (272 Mb), Selaginella (100 Mb) Spirodela (158 Mb) and Utricularia (82 Mb) are plants of very small stature (Fig. 1). However, we provide evidence for the Genome Balance Hypothesis, which suggests that there is selective pressure on Oropetium to purge proliferating transposons in order to maintain expression balance of networked genes and spacing in centromeres. The complete assembly of complex and highly similar repeat sequences demonstrated here suggests that SMRT sequencing can be used to assemble large and polyploid plant and other eukaryotic genomes, assuming ample sequence coverage and computational resources. SMRT-sequencing-based assemblies provide an opportunity to determine how these regions play a role in genome architecture and dynamics.

Methods

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size.

Plant material

Oropetium thomaeum is a compact resurrection plant that has the smallest known genome among the grasses, at 245 Mb and 9 chromosomes (2n = 2x = 18; 1C = 0.25 pg)17. We estimated the genome size to be 250 Mb by flow cytometry and 245 Mb by k-mer analysis (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Oropetium thomaeum plants were originally collected in Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India and propagated as previously described11. Oropetium is a member of the Chloridoideae subfamily, a large and diverse group of roughly 1,600 species that contains the orphan crops tef (Eragrostis tef) and finger millet (Eleusine coracana) as well as some turf grasses (such as Bermuda grass, Cynodon dactylon and Zoysia japonica).

SMRT PacBio sequencing

Fifty micrograms of high-molecular-weight Oropetium gDNA was extracted using a modified nuclei preparation method30 followed by an additional high-salt phenol–chloroform purification to minimize contamination. A 20-kb insert SMRTbell library was generated using a 15 kb lower-end size selection protocol on the BluePippin (Sage Science). Initial titration runs were performed to optimize loading on the SMRT Cell for maximum performance. The Oropetium genome was sequenced using 32 SMRT Cells with 4-h collections and P6-C4 chemistry on the PacBio RS II platform (Pacific Biosciences).

HGAP genome assembly

The Oropetium genome was assembled using the RS_HGAP_Assembly.3 protocol for assembly and Quiver for genome polishing in SMRT Analysis v2.3.012. This consisted of a three-step process involving (1) generation of preassembled reads with improved consensus accuracy; (2) assembly of the genome through overlap consensus accuracy using Celera; and (3) one round of genome polishing with Quiver. For HGAP, the following parameters were used: PreAssembler Filter v1 (minimum sub-read length = 3,000 bp, minimum polymerase read quality = 0.80, minimum polymerase read length = 3,000 bp); PreAssembler v2 (minimum seed length = 16,000 bp, number of seed read chunks = 6, alignment candidates per chunk = 10, total alignment candidates = 24, min coverage for correction = 6); AssembleUnitig v1 (target genome coverage = 30, overlap error rate = 0.06, minimum overlap = 40 bp and overlap k-mer = 14); and BLASR v1 mapping of reads for genome polishing with Quiver (max divergence percentage = 30, minimum anchor size = 12). A second round of genome polishing was performed using Quiver (SMRT Analysis v2.3.0) to further improve the site-specific consensus accuracy of the assembly. The following Quiver parameters were used for genome polishing: filtering (minimum sub-read length = 3,000 bp, minimum polymerase read quality = 0.80, minimum polymerase read length = 3,000 bp); mapping (maximum divergence percentage = 30, minimum anchor size = 12). Default parameters were otherwise employed for both HGAP assembly and Quiver protocols.

Falcon and MHAP assemblies

We also tested other assemblers to compare the PacBio HGAP assembly results (Extended Data Fig. 1i). Raw PacBio reads were error-corrected and assembled using Falcon and MHAP under default parameters. The Falcon and MHAP assemblies have lower contiguity than the HGAP assembly and have fewer assembled centromere and telomere sequences with a lower average length.

Construction of a genome map using the Irys system for contig anchoring and scaffolding

Genome mapping from BioNano Genomics31 was used to improve the assembly quality of the Oropetium genome with the eventual goal of producing a chromosome-scale assembly. High molecular weight genomic DNA was isolated from fresh Oropetium tissue using the following protocol outline. Three grams of leaves were collected from live Oropetium thomaeum plants and fixed with formaldehyde. After blending with a tissue homogenizer in isolation buffer, a filtration step and Triton-X washing treatment were performed. The nuclei were purified on percoll cushions. The nuclei were washed extensively and embedded in low melting agarose at different dilutions. Finally, the DNA plugs were treated with a lysis buffer containing detergent, proteinase K and β-mercaptoethanol (BME). In total, 53 Gb of data (>100 kb) were collected representing ~200× genome coverage with a molecule N50 length of 169 kb (Extended Data Fig. 5a). The size distribution was lower than expected and is probably a result of impurities during high-molecular-weight gDNA isolation that would cause shearing and inhibition of enzymes. Molecules were de novo assembled as previously described32. Two genome maps were assembled at different stringencies, map set 1 has 402 maps with an N50 length of 725 kb and spans 216 Mb (Extended Data Fig. 5b); the second genome map has 214 maps and an N50 of 1.674 Mb. Combining the genome maps with the PacBio assembly to produce a hybrid scaffold was performed sequentially with the two genome maps. The scaffolding merged 90 contigs producing an assembly of 46 primary scaffolds covering 94% of the sequence assembly with an N50 of 7.8 Mb; in total there are 535 scaffolds with an N50 of 7.1 Mb and total assembled size of 244 Mb.

Variant calling using Illumina data

WGS Illumina sequences from Oropetium gDNA were used to assess the error rate of the PacBio assembly and residual within-genome heterozygosity (Supplementary Table 5). Raw Illumina HiSeq data from three different libraries of 570-bp insert, 1-kb insert and 3-kb insert sizes were trimmed for quality using Trimmomatic (v.0.32; ref. 33). Illumina sequence adaptors were removed, leading low quality (below quality 3) and N base pairs were trimmed, and reads were scanned using a 4-bp sliding window and trimmed when the average quality per base dropped below 30. Read pairs where both reads were ultimately of at least 36 bp in length following this quality control process were retained and used for subsequent analyses.

Quality trimmed data were aligned to our assembly using BWA mem (v. 0.7.12-r1039)34. Duplicate alignments were marked using Picard tools v.1.104 MarkDuplicates (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). Genome Analysis Toolkit (v.3.3.0)35 IndelRealigner was used to perform local realignment around indels, followed by application of GATK HaplotypeCaller to call variants. Identified single nucleotide polymorphisms were filtered by depth, strand bias, mapping quality and read position. Identified indels were filtered by depth, strand bias and read position.

The native error rate of raw PacBio reads is in the range of 15–20%, raising the possibility that residual sequencing errors may be introduced into the final assembly of the Oropetium genome. Homozygous mismatches are classified as sequencing errors, and heterozygous mismatches indicate sites of heterozygosity. The accuracy rate is very high at 99.99995%, and a relatively high proportion of the errors (two-thirds) are small insertions or deletions (indels). The accuracy rate is similar to those obtained with WGS Sanger approaches5,36 and is higher than those reported for most NGS-based assemblies. The estimated residual within-genome heterozygosity for the Oropetium genome is very low at 0.087%, which probably contributed to the high contiguity of the assembly. This suggests that provided sufficient coverage, a PacBio SMRT-only approach can produce a high-quality complete plant genome.

Repeat annotation

To structurally annotate repeat sequences in the Oropetium genome, we began by discovering repetitive elements through application of the REPET v.2.2 packages TEdenovo and TEannot37. The TEdenovo pipeline compares the genome with itself to identify and classify repeated genomic elements. All-by-all alignments were conducted with NCBI-BLAST+ using default TEdenovo parameters. LTRharvest38 was used for structural detection. During clustering, Grouper, Recon and Plier steps were invoked both with and without structural detection. Consensus building was performed using default parameters. During consensus detect features, repeat scout39 was invoked, and Pfam26.0 HMM profiles40 and Repbase (v18.08) nucleotide and amino acid databanks were used. Finally, consensus classification, filtering and clustering were performed using default parameters.

Output from the TEdenovo pipeline was used as input to the TEannot pipeline. This pipeline mines the genome sequence using repeated sequences identified in the previous TEdenovo pipeline to produce classified non-redundant consensus repeat sequences along with short simple repeats, which are exported to GFF3 format. First, a set of perfectly matching sequences from the TEdenovo-output transposable elements (TE) library was selected by running a subset of the TEannot pipeline, producing a working reference TE library. This TE library was used in a full run of the TEannot pipeline. For alignment of the reference TE library, NCBI-BLAST+ was used, and blaster, repeat masker and censor steps were run both on the reference TE library and on randomized chunks. Filtering was applied using default parameters. Short simple repeats were identified using the crossmatch engine. Merging was performed using default parameters. For comparisons, Repbase (v18.08) nucleotide and amino acids databanks were used. Finally, filtering was applied using default parameters, and annotations were exported to GFF3 format.

To classify identified repeats, non-redundant consensus repeat sequences as output by TEanno were annotated via PASTEClassifier v1.0 https://urgi.versailles.inra.fr/Tools/PASTEClassifier/README). To classify these sequences, Repbase (v18.08)41 nucleotide and amino acid sequences were used, as were Pfam v26.0 (http://pfam.xfam.org/) HMM repeat profiles. Finally, identified LTRs were classified as Gypsy if homology or motif evidence existed for Gypsy and not for Copia, classified as Copia if the opposite were true, and otherwise classified as unknown.

Centromere and telomere identification

Centromeric repeats were identified using an approach outlined in ref. 42. Tandem repeat finder (TRF, Version 4.07b)43 was used to find tandem repeats using the parameters ‘1 1 2 80 5 200 2000-d –h’ in order to find high order repeats. The resulting ‘.dat file’ was transformed into a GFF3 file, which was used to identify telomeric and centromeric repeats. To identify the centromeric repeats, the largest repeat arrays (period length X copy number) were identified and clustered. Clustered centromeric repeat regions were transformed into FASTA files and aligned using clustalX to identify array sequence composition and orientation. The base centromere repeat was 155 bp dimers (310 bp), trimers (465 bp) and tetramers (620 bp) (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1). The three largest centromeric arrays (contigs 003, 028 and 064) were >400 kb and resolved into large inverted repeats, consistent with them being full length. The telomeric repeats were identified by searching the ends of contigs for short (~7 bp) high copy number repeats; 18 telomeric repeat sequences with the monomer ‘AAACCCT’ were identified (Extended Data Table 1).

Transcriptome assembly

Total RNA was extracted from fresh, desiccated and 24-h post rehydration Oropetium leaf tissues with 2 biological replicates collected for each tissue. RNA-seq libraries were prepared from the total RNA and bar-coded using TruSeq RNA Sample Prep Kits (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Raw Illumina RNA-seq data from the six libraries were trimmed for quality using Trimmomatic (v.0.32; ref. 33). Illumina sequence adaptors were removed, then leading low-quality (below quality 3) and N base pairs were trimmed and, finally, resulting trimmed reads were scanned using a 4-bp sliding window and cut when the average quality per base dropped below 30. Read pairs where both reads were ultimately of at least 36 base pairs in length following this quality control process were retained and used for subsequent analyses. Trinity (v.r20140717)44 was used to assemble quality filtered data. Assembled transcripts were aligned to our genome sequence using NCBI blastn v.2.2.30+ with an e-value cut-off of 1 × 10−5. Successfully aligned transcripts were clustered at 90% identity using CD-HIT (v. 4.5.4)45, with representative sequences from each cluster retained and used to help parameterize gene calling. Eighty-seven per cent of the trimmed RNA-seq reads aligned to the Oropetium genome, suggesting that the genome is largely complete (Supplementary Table 5). Reads that failed to align may have been contaminants from other organisms.

Gene annotation

Maker v2.31.846 (http://www.yandell-lab.org/software/maker.html) was used to identify putative genes. Aligned and representative sequences from our transcriptome assembly were input to Maker as expressed sequence tag evidence. Rice and Brachypodium proteome sequences clustered at 90% identity using CD-HIT (v. 4.5.4)45 with representative sequences from each cluster retained and input to Maker as multi-organismal protein homology evidence. The Oropetium repeat database was input to Maker as a custom repeat library. SNAPhmm, Augustus, and GeneMarkHMM were invoked by Maker and were initially trained using rice and maize. Only genes for which the encoded protein was predicted to contain a complete open reading frame were retained.

On the basis of the gene annotations provided by Maker, cufflinks (v2.2.1)47 was used to identify predicted genes without empirical expression evidence. Quality-trimmed data from all six RNA-seq libraries were input simultaneously to cufflinks, with results used to identify genes with and without expression.

Protein sequences from genes predicted by Maker were functionally annotated using NCBI blastp v.2.2.30+ versus the NCBI non-redundant refseq protein database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/), versus the UniProt database48, and using InterProScan (v. 5.6-48.0)49.

Finally, Maker-predicted genes were pruned based on a Maker-defined annotation edit distanced (AED) score that measures distance between the predicted gene and the evidence input to Maker, non-redundant (NR) annotation, Uniprot annotation, InterProScan annotation and expression level as output by cufflinks. Genes were removed that had no alignment evidence (AED = 1), no sequence match to either the NR or Uniprot databases, no InterProScan predicted domains and no expression evidence in our RNA-seq data.

Synteny and comparative genomics

Genome data sets from Setaria, Sorghum, rice and Brachypodium were downloaded from Phytozome (version 9.1) and subject to pairwise genome alignments against the Oropetium genome. For each pairwise alignment, the coding sequences of predicted gene models are compared to each other using adaptive seeds50. Our synteny search pipeline defines syntenic blocks by chaining the large-scale alignment tool (LAST) hits with a distance cut-off of 20 genes apart, also requiring at least four gene pairs per syntenic block. The syntenic blocks were further screened using QUOTA-ALIGN51 to retain one-to-one blocks and to exclude weak blocks derived from shared ancient duplications. The resulting dot plots were visually inspected to confirm the structural similarity of the Oropetium genome in relation to other genomes (Extended Data Fig. 3a–e).

Pairwise genomic alignments, described above, combined with OrthoMCL52 analyses filtered to one-to-one hits were used to identify orthologous gene clusters between Oropetium and Sorghum, rice, Vitis and Arabidopsis. The complete Oropetium–Arabidopsis orthologue list was then filtered to focus on genes with functional data in the STRING v9.1 global Arabidopsis protein interaction network53. Gene expression patterns and duplicated genes (tandem and whole-genome duplicates) were mapped onto this network using Cytoscape v3.1.154 to identify clusters of co-expressed and interacting duplicate genes, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 6). Various network statistics were calculated using NetworkAnalyzer55, including average number of neighbours (that is, protein interactions) and total number of isolated nodes (that is, without known interactors).

Constructing a gene interaction network

We constructed a gene interaction network for Oropetium on the basis of orthologous relationships with Arabidopsis genes with validated interactions and expression data yielding a network with 4,421 nodes (gene products) with 36,918 edges (interactions). This network encompasses most metabolic pathways including photosynthesis, core anabolic and catabolic processes and stress response pathways (Extended Data Fig. 6).

Accession codes

Primary accessions

BioProject

NCBI Reference Sequence

Data deposits

The genome assembly and annotation have been deposited in CoGe under the accession code 25799 (https://genomevolution.org/CoGe/GenomeInfo.pl?gid=25799), in the NCBI BioProject under PRJNA286116, and in GenBank under accession number LFJQ00000000. Raw PacBio and Illumina reads are available at the Short Read Archive at NCBI under the aforementioned NCBI BioProject. Genome assembly and annotation are also available at http://www.oropetium.org/.

Change history

25 November 2015

An additional affiliation (Center for Genomics and Biotechnology) was added for author H.T.

References

Michael, T. P. & VanBuren, R. Progress, challenges and the future of crop genomes. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 24, 71–81 (2015)

Kellis, M. et al. Defining functional DNA elements in the human genome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 6131–6138 (2014)

The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana . Nature 408, 796–815 (2000)

International Rice Genome Sequencing Project. The map-based sequence of the rice genome. Nature 436, 793–800 (2005)

Paterson, A. H. et al. The Sorghum bicolor genome and the diversification of grasses. Nature 457, 551–556 (2009)

Elert, E. Rice by the numbers: A good grain. Nature 514, S50–S51 (2014)

Schnable, P. S. et al. The B73 maize genome: complexity, diversity, and dynamics. Science 326, 1112–1115 (2009)

International Barley Genome Sequencing Consortium. A physical, genetic and functional sequence assembly of the barley genome. Nature 491, 711–716 (2012)

International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium (IWGSC). A chromosome-based draft sequence of the hexaploid bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) genome. Science 345, 1251788 (2014)

The International Brachypodium Initiative. Genome sequencing and analysis of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon . Nature 463, 763–768 (2010)

Bartels, D. & Mattar, M. Oropetium thomaeum: A resurrection grass with a diploid genome. Maydica 47, 185–192 (2002)

Chin, C.-S. et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nature Methods 10, 563–569 (2013)

Lamesch, P. et al. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): improved gene annotation and new tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D1202–D1210 (2012)

Berlin, K. et al. Assembling large genomes with single-molecule sequencing and locality-sensitive hashing. Nature Biotechnol. 33, 623–630 (2015)

El Baidouri, M. & Panaud, O. Comparative genomic paleontology across plant kingdom reveals the dynamics of TE-driven genome evolution. Genome Biol. Evol. 5, 954–965 (2013)

Michael, T. P. Plant genome size variation: bloating and purging DNA. Brief. Funct. Genomic. 13, 308–317 (2014)

Jones, N. & Pašakinskienė, I. Genome conflict in the gramineae. New Phytol. 165, 391–410 (2005)

Bennetzen, J. L. et al. Reference genome sequence of the model plant Setaria. Nature Biotechnol. 30, 555–561 (2012)

Tang, H., Bowers, J. E., Wang, X. & Paterson, A. H. Angiosperm genome comparisons reveal early polyploidy in the monocot lineage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 472–477 (2010)

Wicker, T., Buchmann, J. P. & Keller, B. Patching gaps in plant genomes results in gene movement and erosion of colinearity. Genome Res. 20, 1229–1237 (2010)

Bennetzen, J. L. & Kellogg, E. A. Do plants have a one-way ticket to genomic obesity? Plant Cell 9, 1509 (1997)

Ibarra-Laclette, E. et al. Architecture and evolution of a minute plant genome. Nature 498, 94–98 (2013)

Leushkin, E. V. et al. The miniature genome of a carnivorous plant Genlisea aurea contains a low number of genes and short non-coding sequences. BMC Genomics 14, 476 (2013)

Wang, W. et al. The Spirodela polyrhiza genome reveals insights into its neotenous reduction fast growth and aquatic lifestyle. Nature Commun. 5, 3311 (2014)

Lyons, E. & Freeling, M. How to usefully compare homologous plant genes and chromosomes as DNA sequences. Plant J. 53, 661–673 (2008)

Freeling, M., Xu, J., Woodhouse, M. & Lisch, D. A solution to the C-value paradox and the function of junk DNA: the Genome Balance Hypothesis. Mol. Plant 8, 899–910 (2015)

Chaisson, M. J. P. et al. Resolving the complexity of the human genome using single-molecule sequencing. Nature 517, 608–611 (2015)

Au, K. F. et al. Characterization of the human ESC transcriptome by hybrid sequencing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, E4821–E4830 (2013)

Beaulieu, J. M., Leitch, I. J., Patel, S., Pendharkar, A. & Knight, C. A. Genome size is a strong predictor of cell size and stomatal density in angiosperms. New Phytol. 179, 975–986 (2008)

Zhang, H.-B., Zhao, X., Ding, X., Paterson, A. H. & Wing, R. A. Preparation of megabase-size DNA from plant nuclei. Plant J. 7, 175–184 (1995)

Lam, E. T. et al. Genome mapping on nanochannel arrays for structural variation analysis and sequence assembly. Nature Biotechnol. 30, 771–776 (2012)

Cao, H. et al. Rapid detection of structural variation in a human genome using nanochannel-based genome mapping technology. GigaScience 3, 34 (2014)

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014)

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009)

McKenna, A. et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303 (2010)

Ming, R. et al. The draft genome of the transgenic tropical fruit tree papaya (Carica papaya Linnaeus). Nature 452, 991–996 (2008)

Flutre, T., Duprat, E., Feuillet, C. & Quesneville, H. Considering transposable element diversification in de novo annotation approaches. PLoS ONE 6, e16526 (2011)

Ellinghaus, D., Kurtz, S. & Willhoeft, U. LTRharvest, an efficient and flexible software for de novo detection of LTR retrotransposons. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 18 (2008)

Price, A. L., Jones, N. C. & Pevzner, P. A. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics 21, i351–i358 (2005)

Finn, R. D. et al. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D222–D230 (2014)

Jurka, J. et al. Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 110, 462–467 (2005)

Melters, D. P. et al. Comparative analysis of tandem repeats from hundreds of species reveals unique insights into centromere evolution. Genome Biol. 14, R10 (2013)

Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 573 (1999)

Grabherr, M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nature Biotechnol. 29, 644–652 (2011)

Huang, Y., Niu, B., Gao, Y., Fu, L. & Li, W. CD-HIT Suite: a web server for clustering and comparing biological sequences. Bioinformatics 26, 680–682 (2010)

Cantarel, B. L. et al. MAKER: an easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed for emerging model organism genomes. Genome Res. 18, 188–196 (2008)

Trapnell, C. et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nature Protocols 7, 562–578 (2012)

Wu, C. H. et al. The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt): an expanding universe of protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, D187–D191 (2006)

Quevillon, E. et al. InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W116–W120 (2005)

Kiełbasa, S. M., Wan, R., Sato, K., Horton, P. & Frith, M. C. Adaptive seeds tame genomic sequence comparison. Genome Res. 21, 487–493 (2011)

Tang, H. et al. Screening synteny blocks in pairwise genome comparisons through integer programming. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 102 (2011)

Li, L., Stoeckert, C. J. & Roos, D. S. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 13, 2178–2189 (2003)

Franceschini, A. et al. STRING v9. 1: protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D808–D815 (2013)

Saito, R. et al. A travel guide to Cytoscape plugins. Nature Methods 9, 1069–1076 (2012)

Doncheva, N. T., Assenov, Y., Domingues, F. S. & Albrecht, M. Topological analysis and interactive visualization of biological networks and protein structures. Nature Protocols 7, 670–685 (2012)

Acknowledgements

This work is supported in part by funding from the National Science foundation (DBI-1401572 to R.V.; DBI-120793 to P.P.E.), USDA NIFA (CO471A-B to M.F.), the Department of Energy (DE-SC0012639 to T.C.M. and T.P.M.; DE-SC-0008769 to T.C.M.), the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center to T.C.M. and the Enterprise Rent-A-Car Institute for Renewable Fuels to T.C.M. Sequencing was provided by Pacific Biosciences under the ‘Most Interesting Genome in the World’ 2014 SMRT grant program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.V., D.Br., T.P.M. and T.C.M. designed and conceived research; D.Ba. and D.C. identified biological material, performed desiccation experiments and extracted DNA and RNA; R.V. prepared DNA for PacBio sequencing; T.P.M., R.V. and T.C.M. performed Illumina sequencing; K.S., R.H. and J.G. performed PacBio sequencing and assembly; B.T.H. and A.H. conducted the BioNano analysis. D.Br., R.V., T.P.M. and T.C.M. annotated genome features; E.L., M.F., D.Bu., R.V., D.Br., H.T., T.P.M., T.C.M. and P.P.E. analysed data; R.V., T.P.M. and T.C.M. wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Figure 1 Summary of the Oropetium genome assembly statistics.

a, Histogram of length distribution of raw P6C4 chemistry PacBio reads. The mean read length of the raw reads is 12,872 bp, and the N50 is 16,485 bp. b, Genome size estimation using k-mer distribution. K-mer distribution of unassembled Oropetium Illumina WGS reads. K-mer frequency displays a unimodal curve indicating a low rate of heterozygosity in the Oropetium genome. Frequency distribution suggests a genome size of ~245 Mb, consistent with flow-cytometry-based estimations. c, SMRT sequencing raw read, preassembly and assembly statistics. d, e, The distribution of the contig N50 length (d) and scaffold N50 length (e) of all published plant genomes is plotted. The average contig N50 length for published plant genomes is ~50 kb compared to 2.4 Mb for Oropetium. f, g, Repeat density (as a function of percentage repeats) (f) and GC content (g) are plotted at a scaled position along each contig. Each contig was divided into 5,000 sliding windows with each window representing 0.02% of the contig length and the averages of each scaled sliding window are plotted. Repeat content and GC content do not vary at the ends of contigs. h, Estimated accuracy of SMRT PacBio assembly and within-genome heterozygosity. i, Comparison of HGAP Falcon and MHAP PacBio assemblers.

Extended Data Figure 2 PacBio sequencing and assembly completely resolves the Oropetium centromeres.

a, The Oropetium centromere repeat base is 155 bp (red arrow), whereas they are also found in dimer (310 bp, grey arrow), trimer (465 bp, black arrow) and tetramer (620 bp, white arrow) form. b, As the copy number of a repeat increases, the match identity between monomers in the repeat decreases. c, The inverted repeat structure of the entire centromere on contig028 with a 60 kb spacer (blue box); arrows are as in a. d, Consensus 155 bp centromere monomer. e, Integrated genome browser view of centromere repeat, LTRs and predicted genes on contig028.

Extended Data Figure 3 Macrosynteny patterns and comparative genomics between the grasses.

a–e, Macrosynteny of Oropetium versus Oropetium (a); Oropetium versus Brachypodium (b); Oropetium versus rice (c); Oropetium versus Setaria (d); and Oropetium versus Sorghum (e). f, Genome compaction in Oropetium compared to related grass genomes. Syntenic block span is based on regions that show conserved synteny across all five genomes. Syntenic gene and coding DNA sequences span is based on 13,683 genes that are retained as genes in orthologous locations across all five genomes. The ratio compared to Oropetium is given in brackets.

Extended Data Figure 4 Expansion of intragenic and pericentric regions in Sorghum compared to Oropetium.

a, A GEvo sequence similarity graphic of an Oropetium gene (upper) and its orthologous Sorghum gene (lower). Blast hits (high-scoring segment pairs) are denoted by red rectangles, and syntenic hits are connected by a red line. The green rectangles on the model line of Sorghum are conserved noncoding sequences (CNS) computed between Sorghum and rice; the expanse of CNS coverage defines ‘gene space’. Within the oval are three CNS that may be spatially constrained. The expanded interspersed sequences are annotated at the bottom in black. b, Pericentric region expansion in Sorghum compared to Oropetium. A syntenic dot plot of the Sorghum and Oropetium genomes is plotted. Oropetium contigs are ordered based on synteny with Sorghum. Hits are coloured based on Ks divergence, with purple blocks corresponding to 1:1 orthologous regions and other colours corresponding to retained genes from the rho and sigma WGDs. Pericentric regions in Sorghum have few syntenic matches to Oropetium, suggesting that much of the expansion occurred in pericentric regions.

Extended Data Figure 5 Assembly improvement using a BioNano-based genome map from the Irys system.

a, Distribution of molecule size for raw single-molecule genome mapping data. Size of single molecules in nanochannel arrays is plotted. b, Integration of the genome map with the genome assembly. Overlap between the PacBio-based contigs and the genome map. Each line shows a single PacBio contig in green; genome maps are shown in light blue.

Extended Data Figure 6 Network statistics for tandem duplicated genes.

a, Tandem duplicated genes in the metabolic network are shown in pink. b, Distribution of shared neighbours. c, The average number of neighbours.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Text and References and Supplementary Tables 1-6. (PDF 354 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported licence. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

VanBuren, R., Bryant, D., Edger, P. et al. Single-molecule sequencing of the desiccation-tolerant grass Oropetium thomaeum. Nature 527, 508–511 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15714

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15714

This article is cited by

-

Specific metabolic and cellular mechanisms of the vegetative desiccation tolerance in resurrection plants for adaptation to extreme dryness

Planta (2024)

-

A high-quality chromosome-level Eutrema salsugineum genome, an extremophile plant model

BMC Genomics (2023)

-

A genome assembly for Orinus kokonorica provides insights into the origin, adaptive evolution and further diversification of two closely related grass genera

Communications Biology (2023)

-

Pangenomic analysis identifies structural variation associated with heat tolerance in pearl millet

Nature Genetics (2023)

-

Next-generation sequencing technology: a boon to agriculture

Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.