Abstract

The inability to appropriately ventilate neonates shortly after their birth could be related in rare cases to chest-wall rigidity caused by the placental transfer of fentanyl. Although this adverse effect is recognized when fentanyl is administered to neonates after their birth, the prenatal phenomenon is less known. Treatment with either naloxone or muscle relaxants reverses the fentanyl effect and may prevent unnecessary excessive ventilatory settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fentanyl is used as a sedative and an analgesic in the care of critically ill infants. Its most known side effect is respiratory depression. A recognized uncommon side effect of fentanyl is muscle and chest wall rigidity. Reports on this phenomenon caused by prenatal fentanyl exposure are rare, when used in critically ill mothers. We report a case of a preterm infant born with chest-wall rigidity caused by intrauterine exposure to a high dose of fentanyl that resolved after naloxone treatment.

Case report

This infant was delivered by an emergent cesarean section at 28 weeks’ gestation by an 18-year-old woman who was admitted 12 h earlier to the respiratory intensive care unit with pyelonephritis and adult respiratory distress syndrome. Despite treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics, intravenous fluids and inotropes, her hemodynamic and respiratory condition continued to deteriorate. To control her respiratory function better, she was ventilated and treated with a high dose of fentanyl (20 mcg−1 kg−1 h−1); however, no respiratory improvement was achieved, and it was decided to perform a cesarean section.

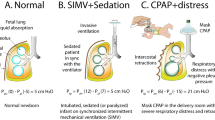

The female infant (birth weight 1220 g) was born apneic and hypotonic, and needed immediate intubation and ventilation. Surfactant (Curosurf-100 mg kg−1) was administered via the endotracheal tube, which was placed at 7.2 cm attached to the upper lip. Clinical evaluation upon arrival to the neonatal intensive care unit at 15 min after birth showed normal heart rate, peripheral pulses and blood pressure, normal fontanelle, and equal air entry to both lungs upon ventilation. No spontaneous respirations were detected and the chest moved only with response to high pressure (positive inspiratory pressure 25 cm H2O, positive end expiratory pressure 6 cm H2O) via Neopuff. Chest X-ray performed at 30 min of age showed respiratory distress syndrome without air leaks and correct position of the endotracheal tube. On connecting to the ventilator, she developed recurrent de-saturation episodes and periodic cessations in the chest-wall elevation requiring frequent bag-assisted ventilation. Mean airway pressure was gradually increased to 16 cm H2O via different ventilation modes (conventional mechanical ventilation and high-frequency ventilation) without achieving adequate chest expansion. Arterial blood gases showed worsening respiratory acidosis. The infant remained hypotonic. No seizure activity was observed. At age 2 h, in view of chest-wall rigidity combined with generalized hypotonia, we postulated adverse effects of placental transfer of fentanyl. Accordingly, 0.1 mg kg−1 naloxone was administered. Within minutes the infant started to breathe and move her limbs. From this point onwards, ventilation and oxygenation were easily accomplished and it was possible to rapidly decrease the ventilation parameters to a minimum with no episodes of de-saturation or difficulties in chest expansion. The infant was extubated 2 days after birth and was discharged from the neonatal intensive care unit 56 days after birth. Cranial ultrasound evaluations on day 3, at 1 week of age and before discharge were normal. Subsequent developmental course and neurological examination at 6 months after birth were normal.

Discussion

Fentanyl, one of the potent systemic opioids used for maternal analgesia during labor, readily crosses the placenta,1, 2 and may induce adverse effects in the fetus and the neonate.3 When administered to the neonate, potential adverse effects are respiratory depression, de-saturation episodes, lower heart rate and sleep-state disturbances.3 Less frequently seen are the neuromuscular adverse effects of fentanyl, including abnormal muscle movements, such as sucking or tonic–clonic movements, but also laryngeal spasm and chest-wall rigidity in up to 4% of the treated term and preterm infants even when low doses of fentanyl are given.4 The exact mechanism of muscle rigidity induced by fentanyl is still unknown.5

Information on the neonatal pharmacokinetics of placentally-transferred fentanyl shortly after birth is limited.1, 6 Moreover, it has been recently shown that there is a positive correlation between a higher rate of fentanyl clearance after birth, and advanced gestational age and birth weight, whereas in preterm infants the clearance spectrum is very wide mainly because of hepatic immaturity.7 Therefore, extremely preterm infants are at an increased risk of chest-wall rigidity induced by the placental fentanyl transfer.

To our knowledge this is the third reported case of chest-wall rigidity described in a preterm infant after maternal administration of fentanyl before (as in our case) or during cesarean section. In the case described by Lindemann,8 extremely high ventilation pressures (positive inspiratory pressures of 60 to 70 cm H2O) were required to inflate the lungs of a 31 weeks’ gestation neonate, while increase in chest wall compliance was achieved only after the infusion of naloxone and pancoronium. By a similar placental fentanyl transfer mechanism, Bolisetty et al.9 reported the occurrence of chest-wall rigidity in a term infant after maternal intrathecal administration of fentanyl before elective cesarean section.

The cases reporting the possibility of neonatal chest-wall rigidity after prenatal fentanyl administration emphasize the importance of recognition and diagnosis of this phenomenon that may prevent unnecessary barotrauma. Thus, in all cases of chest-wall rigidity shortly after birth, the possibility of placental transfer of fentanyl may be raised and treatment may be considered.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

Giroux M, Teixera MG, Dumas JC, Desprats R, Grandjean H, Houin G . Influence of maternal blood flow on the placental transfer of three opioids–fentanyl, alfentanil, sufentanil. Biol Neonate 1997; 72: 133–141.

Moises EC, de Barros Duarte L, de Carvalho Cavalli R, Lanchote VL, Duarte G, da Cunha SP . Pharmacokinetics and transplacental distribution of fentanyl in epidural anesthesia for normal pregnant women. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 61: 517–522.

Nikkola EM, Jahnukainen TJ, Ekblad UU, Kero PO, Salonen MA . Neonatal monitoring after maternal fentanyl analgesia in labor. J Clin Monit Comput 2000; 16: 597–608.

Fahnenstich H, Steffan J, Kau N, Bartmann P . Fentanyl-induced chest wall rigidity and laryngospasm in preterm and term infants. Crit Care Med 2000; 28: 836–839.

Turski L, Havemann U, Schwarz M, Kuschinsky K . Disinhibition of nigral GABA output neurons mediates muscular rigidity elicited by striatal opioid receptor stimulation. Life Sci 1982; 31: 2327–2330.

Gauntlett IS, Fisher DM, Hertzka RE, Kuhls E, Spellman MJ, Rudolph C . Pharmacokinetics of fentanyl in neonatal humans and lambs: effects of age. Anesthesiology 1988; 69: 683–687.

Saarenmaa E, Neuvonen PJ, Fellman V . Gestational age and birth weight effects on plasma clearance of fentanyl in newborn infants. J Pediatr 2000; 136: 767–770.

Lindemann R . Respiratory muscle rigidity in a preterm infant after use of fentanyl during Caesarean section. Eur J Pediatr 1998; 157: 1012–1013.

Bolisetty S, Kitchanan S, Whitehall J . Generalized muscle rigidity in a neonate following intrathecal fentanyl during caesarean delivery. Intensive Care Med 1999; 25: 1337.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Eventov-Friedman, S., Rozin, I. & Shinwell, E. Case of chest-wall rigidity in a preterm infant caused by prenatal fentanyl administration. J Perinatol 30, 149–150 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2009.66

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2009.66