Abstract

Background

Self-medication with chloroquine is common in Ibadan, Sub-Sahara Africa. Retinopathy from chloroquine is not uncommon. The aim was to determine the pattern of presentation.

Methodology

Cases of Chloroquine retinopathy seen at the Retina and Vitreous Unit of the University College Hospital, Ibadan between 2008 and 2014 were reviewed. Information on age, sex, duration of chloroquine use, and visual loss were retrieved. Visual acuity at presentation, anterior, and posterior segment findings were documented. The results were analyzed using proportions and percentages.

Results

Fourteen cases were seen during the study period. Mean age was 50.7 years. Male to female ratio was 3.5 : 1. Average duration of visual loss before presentation was 2.7 years. Average duration of self-medication with chloroquine was 5.3 years. Presenting visual acuity showed 2(14%) cases of bilateral blindness(VA<3/60 in both eyes); 5(35.7%) cases of uniocular blindness; three cases of bilateral low vision(VA worse than 6/18 but better than 3/60). Anterior segment examination showed abnormal sluggish pupillary reaction in those with severe affectation. Dilated fundoscopy showed features ranging from mild macular pigmentary changes and bulls eye maculopathy to overt extensive retinal degeneration involving the posterior pole, attenuation of retinal vessels, optic atrophy, and beaten bronze appearance of atrophic maculopathy.

Conclusion

Chloroquine retinopathy is not uncommon in Ibadan, Sub-Sahara Africa. Bulls eye maculopathy, extensive retinal, and macular degeneration with optic atrophy are the main presentations. Public health education is imperative.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cambaiaggi and Hobbs et al1, 2 first described the effect of chloroquine on the eye. A total dose between 100 and 300 g is needed to cause toxicity, which is equivalent to about 200 mg per day for 3 years.3 Cloroquine is cheap and readily available as over the counter medication in Nigeria. Nigeria has more reported cases of malaria and deaths due to malaria than any other country in the world.4 Most patients would have used chloroquine for fever before hospital presentation. Most non-skilled workers use chloroquine as prophylaxis for malaria in Nigeria. A study showed that its self-medication is so common that it is a common cause of heart block in Nigerians.5 Chloroquine deposits in the retinal pigment epithelium leading to its degeneration and that of the neurosensory retina leading to irreversible visual loss. In Nigeria, hospital presentation is usually a last resort for most people hence the late presentation of chloroquine retinopathy. The aim of this study was to describe the pattern of presentation of Nigerian patients with chloroquine retinopathy seen at the Retina and Vitreous Unit of the Department of Ophthalmology, University College Hospital, Ibadan between 2008 and 2014.

Materials and methods

The retinal register that contain retina unit cases seen in the department of ophthalmology, University College Hospital, Ibadan was reviewed and all cases of chloroquine retinopathy retrieved and studied to determine the pattern of presentation. Fourteen cases were seen during the period under study. Information on age, sex, duration of chloroquine use, and visual loss were retrieved. Visual acuity at presentation, anterior, and posterior segment findings were also documented. The results were analyzed using proportions and percentages.

Results

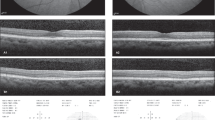

Fourteen cases were seen during the study period. Mean age was 50.7 years. Male to female ratio was 3.5 : 1. Average duration of visual loss before presentation was 2.7 years. Average duration of self-medication with chloroquine was 5.3 years. Presenting visual acuity showed 2(14%) cases of bilateral blindness (VA<3/60 in both eyes); 5(35.7%) cases of uniocular blindness; 3 cases of bilateral low vision (VA worse than 6/18 but better than 3/60). Anterior segment examination showed abnormal sluggish pupillary reaction in those with severe affectation. Dilated fundoscopy showed features ranging from mild macular pigmentary changes and bulls eye maculopathy to overt extensive retinal degeneration involving the posterior pole, attenuation of retinal vessels, optic atrophy, and beaten bronze appearance of atrophic maculopathy (Table 1 and Figures 1, 2, 3, 4). A striking picture noted included a sharp demarcation between the degenerated posterior pole and the healthy retinal and the retinal pigment epithelium in the periphery (Figure 3).

Bull’s eye maculopathy: patient 3 (a) and patient 4 (b) note a ring of hypopigmentation surrounding the fovea signifying RPE window defect degeneration. The upper pictures showed generalized degenerative mottling of the posterior pole. The retina in (b) also showed vascular attenuation with some disc pallor.

Discussion

The study showed that self-medication with chloroquine was the major cause of retinopathy in the patients presented. Self-medication of chloroquine is a problem in Nigeria.6 Males are more affected in this study. In Calabar, south eastern Nigeria, males are the major abusers of chloroquine.6 The drug is sold over the counter to treat cases of fever through self-medication. In Ghana, a neighboring country, chloroquine is the most commonly kept antimalarial medication in the homes.7

In this study, about one-third of the eyes were blind at presentation with the rest at risk of severe visual loss. Anterior segment finding of sluggishly reacting pupils and afferent nerve defect is a reflection of the posterior segment involvement.

Bull’s eye manifestation comprising of an annular parafoveal chorioretinal atrophy have been described and is pathognomonic of chloroquine retinopathy.8 The chloroquine accumulates in melanin of the retinal pigment epithelium. However in Nigerians as seen in this study, in addition to the bull’s eye maculopathy, most patients with chloroquine retinopathy present with diffuse chorioretinal atrophy involving a large area of the posterior pole with a sharp demarcation between the posterior pole and the retinal periphery. This suggests the affinity of chloroquine for the retina in the posterior pole of the eye. Extensive retinal degeneration is explained by the late presentation seen in the patients.

Blindness from Chloroquine is irreversible and unfortunately visual loss will progress despite cessation of therapy. Three patients with retinopathy are told to stop using chloroquine and use alternative antimalarials. Most of these patients with low vision will benefit from low vision aids.

Conclusion and recommendation

Chloroquine retinopathy is not uncommon in Ibadan, Sub-Sahara Africa. Bulls eye maculopathy and extensive retinal and macular degeneration are the main presentation. It is recommended that enabling law should be made by government to withdraw chloroquine from the market as is done in Malawi.9 Public health education is imperative in Nigeria and Sub-Sahara Africa against self-medication with chloroquine. Currently there are alternative medications to chloroquine for malaria treatment and should be considered.

References

Cambiaggi A . Unusual ocular lesions in a case of systemic lupus erythromatosis. AMA Arch Ophthalmol 1957; 57: 451–453.

Hobbs H, Sorsby A, Freedman A . Retinopathy following chloroquine therapy. Lancet 1959; 2: 478–480.

Michaelides M, Stover NB, Francis PJ, Weleber RG . Retinal toxicity associated with hydroxyl chloroquine and chloroquine: risk factors, screening, and progression despite cessation of therapy. Arch Ophthalmol 2011; 129 (1): 30–39.

Center for disease control and preventionhttp://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/countries/nigeria/what/malaria.htm. (Accessed 12 April 2015).

Ihenacho HN, Magulike E . Chloroquine abuse and heart block in Africans. Aust N Z J Med 1989; 19 (1): 17–21.

Ezedinachi EN, Ejezie GC, Emeribe AO . Problems of chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum in Nigeria: one antimalaria drugs' utilisation in metropolitan Calabar. Cent Afr J Med 1991; 37 (1): 16–20.

Abuaku BK, Koram AK, Binka FN . Antimalarial drug use among caregivers in Ghana. Afr Health Sci 2004; 4 (3): 171–177.

American Academy of Ophthalmology 2012 Retina and Vitreous(2011–2012ed). ISBN 9781615251193.

Frosch AE, Laufer MK, Mathanga DP, Takala-Harrison S, Skarbinski J, Claassen CW et al. Return of widespread chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium falciparum to Malawi. J Infect Dis 2014; 210 (7): 1110–1114.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the records staff of the Eye Clinic, Department of Ophthalmology, University College Hospital, Ibadan for supplying the records of patients.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oluleye, T., Babalola, Y. & Ijaduola, M. Chloroquine retinopathy: pattern of presentation in Ibadan, Sub-Sahara Africa. Eye 30, 64–67 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2015.185

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2015.185

This article is cited by

-

Chloroquine

Reactions Weekly (2016)