Key Points

-

Evaluates how service reconfiguration can create opportunities for research.

-

Stresses the need to engage clinicians, the public and patients in identifying research questions.

-

Underlines the importance of early identification of a funder.

-

Highlights how the NIHR has become a key provider of support for clinical research through direct funding and provision.

Abstract

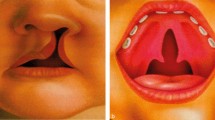

In the UK around a thousand children are born annually with a cleft lip and/or palate that requires treatment. In the last decade services have been centralised in the UK reducing the 57 centres operating on these children in 1998, down to 11 centres or managed clinical networks in 2011. While the rationale for centralisation was to improve the standard of care (and in so doing the outcome) for children born with cleft lip and/or palate, research was central to this process. We illustrate how research informed and shaped this service rationalisation and how it facilitated the emergence of a research culture within the newly configured teams. We also describe how these changes in service provision were linked to the development of a national research strategy and to the identification of the resources necessary to support this strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cleft lip and palate is a common congenital anomaly in humans. About a thousand children are born in the UK each year with some form of cleft lip and/or palate. This anomaly impacts on the individual, their families, the healthcare system and society. Different forms of clefting can affect appearance, speech, hearing, general health and social integration and treatment requires the input of a range of healthcare professionals. There are also data suggesting that people with cleft lip and/or palate have lower educational attainment and reduced life expectancy.1,2

The evidence to inform clinical care for children with cleft lip and/or palate is limited. Much clinical practise is supported by case reports or case series. Large scale observational studies and randomised trials need access to clinical populations and an adequate infrastructure for clinical research.

In the UK we are well placed to make an important contribution to research in children with cleft lip and/or palate, as the population is contained within a relatively small island and almost all children are treated within the NHS and monitored through a single information system. Until recently, the service was spread across many centres and few clinicians were engaged in audit or research projects. We describe how audit informed the process of centralisation and how a research strategy and infrastructure have been developed and embedded in the emerging clinical networks.

The importance of evidence informing service rationalisation

In the late 1980s and early 1990s comparisons between outcomes in selected UK centres and those in European centres indicated that care for children born with a cleft lip and palate in the UK was suboptimal.3,4 The Department of Health responded by inviting the Clinical Standards Advisory Group (CSAG) to carry out an enquiry. The CSAG was set up by the UK health ministers in 1991 as an independent source of expert advice on access to availability of selected NHS specialised services.

The CSAG committee commissioned a research team to carry out an audit in order to describe the care and outcome in every non-syndromic case of unilateral cleft lip and palate (UCLP) aged 5 and 12 years, treated in the UK over a two year period. Information was collected on the process of care and key outcomes were measured including speech, hearing, dentoalveolar relations, bone grafting, facial appearance and child/parent satisfaction with treatment outcomes. The results of this audit showed that outcomes were less than satisfactory. For example, poor dental arch relationships were present in 36% of 5-year-olds and 39% of 12-year-olds, indicating that in the region of 40% of children would be likely to need a maxillary osteotomy to correct an underlying skeletal discrepancy between the maxilla and the mandible. This proportion compared unfavourably with the 4% of children treated in leading European centres requiring ostoeotomies.5

Poor outcomes were also seen with alveolar bone grafting, a procedure undertaken around the age of 11 to unite the divided maxilla and allow eruption of adjacent permanent teeth. Most, if not all, children with a UCLP should be offered this operation. However, 16% of 12-year-olds had not received a graft and of those who had, only 58% were successful. In Oslo the success rate of this operation, measured by the same criteria, was over 90%.6

The predominance of low volume operators (nearly 60% of surgeons dealt with only one UCLP case per year) and overall poor quality of results limited detailed exploration of associations between volume and outcome, but the results were strongly suggestive that cleft services should be multidisciplinary and centralised.7,8

The process of centralisation and the development of routine audit

The CSAG committee prepared a report based on this evidence.9 Recommendations were accepted by ministers and the Department of Health announced the establishment of the cleft implementation group (CIG). This was the first time a CSAG report had resulted in a formal process of implementation. The reasons for this included the strength and scientific robustness of the evidence collected, the unanimous clinical support for service rationalisation and that the proposed changes had the support of an active and well informed user/clinician group (Cleft Lip and Palate Association, CLAPA). The 57 centres which were operating on children born with some form of cleft lip and/or palate in the UK have been reduced to 11 centres or managed clinical networks. This process has been both lengthy and challenging. Understandably, many patients and families had developed a strong affinity with their original service providers and did not relish the prospect of change, particularly in many cases where this meant travelling to more geographically distant teams. There is preliminary evidence that outcomes have improved. In several of the centralised networks fewer than 20% of children now have poor dento-alveolar relations compared to 40% in the CSAG study.10 Success rates for alveolar bone grafting are now reported at 85% compared to 58% in the CSAG study.11,12

We have recently secured funding, through a National Institute for Health Services Research (NIHR) programme, to repeat the survey of outcomes in 5-year-old children with UCLP 15 years on from the original CSAG commissioned audit. All centres have agreed to take part in this project and have offered the research team their full cooperation. With fewer centres and a culture of regularly inviting patients and families to review clinics at age five, the re-run of the CSAG study has been easier to execute. However, there have been some additional barriers in the form of increased bureaucracy associated with ethics and permissions through research and development.13

Steps to embedding a culture of routine data collection and developing a strategy for research

In addition to the CSAG report and the influence of the CIG, the Craniofacial Society of Great Britain and Ireland (CFSGB&I) has played an important role in developing an audit culture and a research strategy. The main functions are to organise an annual scientific meeting, sponsor research and comment on medico-political issues relating to cleft lip and palate service provision. These annual meetings facilitate networking between clinicians and researchers and have provided a forum to present and discuss audits and research projects.

In 2003, the CFSGB&I recognised the need to support and develop audit and research and so appointed a research lead and a parallel position in audit. The latter developed protocols for minimum data collection and established a national database currently hosted in the Clinical Effectiveness Unit at the Royal College of Surgeons of England. Given that research activity within the centralising service was limited and there were no agreed research priorities for cleft lip and/or palate the research lead facilitated a two day research workshop in 2005 to demonstrate contemporary research methodology and identify future research priorities. This workshop brought together clinical scientists and clinical leads from the various specialties providing cleft care along with representatives from a potential research funder, the Healing Foundation. This charity was formed in 1999, with founding members from six societies including CFSGB&I and has an overarching aim of raising funds to support people living with disfigurement and visible loss of function. The workshop identified a number of research questions and areas that required further research listed in Table 1. There was also recognition of the need to evaluate the impact of centralisation and to involve parents and children in the development of research questions and methods. The workshop also suggested that consideration be given to the establishment of a gene bank.

The CFSGB&I funded a further workshop in 2007 in order to address the question of the causes of cleft and specifically to discuss the creation of a gene bank for people with cleft lip and/or palate in the UK. Subsequently, the society funded pilot studies to explore the feasibility of establishing such a gene bank. These studies have informed the proposal for the gene backed clinical cohort described below.14

Addressing research priorities

Most of the remaining research priorities identified are now the subject of systematic reviews and/or ongoing research. Researchers in Bristol carried out a systematic review of the early placement of grommets in children born with a cleft palate and showed that there is little evidence to inform practice.15 Researchers in Manchester and Bristol have now been funded by the health technology assessment programme to carry out a feasibility study examining the use of grommets in children born with a cleft palate.

The NIHR programme (described above) has funded further research workshops and a programme of systematic reviews. A review of the evidence to support speech and language interventions is nearly complete and a review of psychosocial interventions in cleft lip and palate is underway. Within this programme there is also the opportunity to study the process of centralisation, the experience of multi-disciplinary working and to evaluate outcomes with a repeat of the CSAG survey. Following the 2005 workshop, researchers from Manchester secured funds from the US National Institute for Health for a trial of the timing of closure of the palate in children with cleft palate (http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00993551).

The NIHR programme funded workshops have also triggered partnerships with the James Lind Alliance (JLA) (http://www.lindalliance.org) and Healthtalkonline (HTO) (http://www.healthtalkonline.org/) that will take forward the issues of user involvement and information provision for people with cleft lip and/or palate and their families. We have secured an NIHR research for patient benefit grant (RfPB) to collect qualitative data about experiences of being in a family where a child was born with a cleft lip/palate and to develop an HTO website.

Securing funding for research infrastructure

The next step in developing research capacity for people born with cleft lip and/or palate has been to secure funding to create the necessary research infrastructure. The Healing Foundation is committed to funding the establishment of a clinical trials unit for cleft, as well as a gene backed clinical cohort study. The clinical trials unit, based in Manchester will provide services to cleft researchers throughout the UK. Its work will be guided by an independently appointed clinical studies group for cleft and craniofacial research and will fit within the current NIHR medicines for children research network.

Researchers in Bristol have been awarded funds to establish a UK birth cohort study with an associated biobank of stored DNA for children (and families) born with a cleft from 2012, informed by previous research workshops, preliminary studies and with the experience of running other birth cohort studies including the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children.16

Lessons Learnt

Service rationalisation offers an opportunity to develop an ethos and structure conducive to clinical research. In order to do this successfully there is a need to invest time in the development of routine audit and shared priorities for research and to provide opportunities for clinicians and researchers from different disciplines to interact and work together on a regular basis.

The reorganisation of centralised cleft services in the UK was informed by high quality audit.9 Centralisation was an opportunity to move from audit to research via workshops that built shared professional space and allowed the discussion and development of ideas and a commitment to research. The identification of a key funder in The Healing Foundation was also crucial as significant funding for large infrastructure projects is difficult to obtain in this relatively small clinical area. The focus on linking a clinical specialty to broader research endeavours has also been critical. Centralisation has created some of the clinical research infrastructure required to run large studies and made readily accessible clinical populations.

Summary

Over the past 15 years there has been significant reorganisation and centralisation of UK cleft services. Not only are improvements in standards of care becoming evident, but important parallel developments initially in multidisciplinary audit, and latterly in research, have been initiated through this reconfiguration. Centralisation has not only raised the profile of this relatively small care group, but also enabled a UK wide coordinated approach to research into cleft lip and palate. This process illustrates how NHS services can provide a platform for national research that has the potential to improve health worldwide.

Disclaimer

This publication presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research scheme (RP-PG-0707-10034). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

References

Mossey P A, Little J, Munger R G, Dixon M J, Shaw W C. Cleft lip and palate. Lancet 2009; 374: 1773–1785.

Persson M, Becker M, Svensson H. Academic achievement in individuals with cleft: a population-based register study. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2012; 49: 153–159.

Mars M, Plint D A, Houston W J, Bergland O, Semb G. The Goslon Yardstick: a new system of assessing dental arch relationships in children with unilateral clefts of the lip and palate. Cleft Palate J 1987; 24: 314–322.

Shaw W C, Dahl E, Asher-McDade C et al. A six-center international study of treatment outcome in patients with clefts of the lip and palate: part 5. General discussion and conclusions. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 1992; 29: 413–418.

Mars M, Asher-McDade C, Brattström V et al. A six-center international study of treatment outcome in patients with clefts of the lip and palate: part 3. Dental arch relationships. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 1992; 29: 405–408.

Bergland O, Semb G, Abyholm F E. Elimination of the residual alveolar cleft by secondary bone grafting and subsequent orthodontic treatment. Cleft Palate J 1986; 23: 175–205.

Williams A C, Sandy J R, Thomas S, Sell D, Sterne J A. Influence of surgeon's experience on speech outcome in cleft lip and palate. Lancet 1999; 354: 1697–1698.

Bearn D, Mildinhall S, Murphy T et al. Cleft lip and palate care in the United Kingdom – the Clinical Standards Advisory Group (CSAG) Study. Part 4: outcome comparisons, training, and conclusions. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2001; 38: 38–43.

Clinical Standards Advisory Group. Cleft lip and/or palate. London: HMSO, 1998.

Hathorn I S, Atack N E, Butcher G et al. Centralization of services: standard setting and outcomes. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2006; 43: 401–405.

Felstead A M, Deacon S, Revington P J. The outcome for secondary alveolar bone grafting in the South West UK region post-CSAG. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2010; 47: 359–362.

Revington P J, McNamara C, Mukarram S, Perera E, Shah H V, Deacon S A. Alveolar bone grafting: results of a national outcome study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010; 92: 643–646.

Sandy J, Kilpatrick N, Persson M et al. Why are multi-centre clinical observational studies still so difficult to run? Br Dent J 2011; 211: 59–61.

Williams L R, Dures E, Waylen A, Ireland T, Rumsey N J, Sandy J R. Approaching parents to take part in a cleft gene bank: a qualitative pilot study. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2011; doi: 10.1597/10-086 [Epub ahead of print].

Ponduri S, Bradley R, Ellis P E, Brookes S T, Sandy J R, Ness A R. The management of otitis media with early routine insertion of grommets in children with cleft palate – a systematic review. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2009; 46: 30–38.

Golding J ; ALSPAC Study Team. The Avon longitudinal study of parents and children (ALSPAC) - study design and collaborative opportunities. Eur J Endocrinol 2004; 151 (Suppl 3): U119–123.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sandy, J., Rumsey, N., Persson, M. et al. Using service rationalisation to build a research network: lessons from the centralisation of UK services for children with cleft lip and palate. Br Dent J 212, 553–555 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.470

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.470

This article is cited by

-

Assessing a training programme for primary care dental practitioners in endodontics of moderate complexity: Pilot data on skills enhancement and treatment outcomes

British Dental Journal (2018)

-

Standards of cleft lip and palate care improved

British Dental Journal (2012)