Abstract

Mammalian sperm acquire fertilizing capacity in the female tract in a process called capacitation. At the molecular level, capacitation requires protein kinase A activation, changes in membrane potential and an increase in intracellular calcium. Inhibition of these pathways results in loss of fertilizing ability in vivo and in vitro. We demonstrated that transient incubation of mouse sperm with Ca2+ ionophore accelerated capacitation and rescued fertilizing capacity in sperm with inactivated PKA function. We now show that a pulse of Ca2+ ionophore induces fertilizing capacity in sperm from infertile CatSper1 (Ca2+ channel), Adcy10 (soluble adenylyl cyclase) and Slo3 (K+ channel) KO mice. In contrast, sperm from infertile mice lacking the Ca2+ efflux pump PMACA4 were not rescued. These results indicate that a transient increase in intracellular Ca2+ can overcome genetic infertility in mice and suggest this approach may prove adaptable to rescue sperm function in certain cases of human male infertility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 1978, Steptoe and Edwards reported the birth of Louise Joy Brown, the first successful “Test-Tube” baby1. A major step toward this achievement occurred in the early 1950’s, when Chang2 and Austin3 demonstrated independently that sperm have to be in the female reproductive tract for a period of time before acquiring fertilizing capacity, a phenomenon now known as sperm capacitation. Capacitation includes all post-ejaculation biochemical and physiological changes that render mammalian sperm able to fertilize4. As part of capacitation, sperm acquire the ability to undergo acrosomal exocytosis4,5 and undergo changes in their motility pattern (i.e., hyperactivation). Molecularly, capacitation is associated with; (1) activation of a cAMP/protein kinase A pathway6; (2) loss of cholesterol7 and other lipid modifications8; (3) increase in intracellular pH (pHi)9; (4) hyperpolarization of the sperm plasma membrane potential10,11,12; (5) increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration [Ca2+]i13; and (6) increase in protein tyrosine phosphorylation14,15. These pathways were first identified as playing a role in capacitation using compounds that either stimulate or block the respective signaling processes. More recently, the essential roles of cAMP, Ca2+ and plasma membrane hyperpolarization were confirmed using knock-out (KO) genetic approaches.

The role of cAMP in capacitation and fertilization was originally asserted using reagents such as cAMP agonists (dibutyryl cAMP, 8-BrcAMP) and antagonists of PKA-dependent pathways (e.g. H89, PKI, rpScAMP), as well as other conditions in which soluble adenylyl cyclase Adcy10 (aka sAC)16,17, the major source of cAMP in sperm, cannot be activated (e.g. HCO3−-free incubation media; addition of KH7, a specific sAC inhibitor)18. These roles of cAMP were confirmed using KO genetic mouse models lacking either the PKA sperm-specific catalytic splicing variant Cα219, or sAC18; these mice are sterile and their sperm cannot fertilize in vitro. Our group has recently demonstrated that hyperpolarizing changes in membrane potential are necessary and sufficient to prepare the sperm for a physiological acrosome reaction20. Accordingly, sperm missing the sperm-specific K+ channel SLO3 cannot hyperpolarize and are infertile21. Finally, Ca2+ was shown to be essential for hyperactivation and the acrosome reaction both by removing it using Ca2+-free incubation media, either with or without chelating agents (i.e., EGTA)22, or by elevating it using Ca2+ ionophores such as A2318723. Consistent with these findings, male mice with the sperm-specific Ca2+ channel complex CatSper gene knocked out are infertile and their sperm are unable to undergo hyperactivation24.

Recently, we found that addition of Ca2+ ionophore A23187 produced a fast increase in intracellular Ca2+ that was accompanied by complete loss of sperm motility23. However, if A23187 is removed after 10 min, intracellular Ca2+ levels dropped and sperm gained hyperactive motility23. In addition to inducing hyperactive motility, this short treatment with Ca2+ ionophore A23187 enhanced the sperm fertilizing capacity. Interestingly, the Ca2+ ionophore pulse supported capacitation in sperm incubated under non-capacitating conditions and it induced hyperactivation and the capacity to fertilize in vitro even under conditions where cAMP-dependent pathways were blocked23. These results suggested that A23187 could overcome defects in the signaling pathways upstream of the increase in intracellular Ca2+ required for capacitation. Here, we tested this hypothesis using infertile genetic KO mouse models. Consistent with our hypothesis, a short A23187 pulse overcomes the infertile phenotypes of CatSper24, sAC18 and SLO3 KO sperm21. Furthermore, our previous results suggested that after A23187 washout, sperm are required to reduce the intracellular Ca2+ concentrations to gain hyperactivation and fertilizing capacity23. Consistent with this hypothesis, sperm lacking the Ca2+ efflux pump PMCA4, which mediates Ca2+ extrusion25, were not rescued by treatment with ionophore, suggesting that this ATPase is required downstream to remove excess intracellular Ca2+.

Results

A23187 improves hyperactivation and fertilizing capacity of sperm from C57BL/6J mice

Sperm physiology and their ability to fertilize in vitro is highly dependent upon genetic background26. Over the years, C57BL/6J has been a common genetic background for studying KO genetic mouse models. Unfortunately, relative to sperm from mice of other genetic backgrounds, specifically CD1(ICR) mice, sperm from C57BL/6J exhibit significantly lower hyperactivation rates when capacitated27 (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Table I) and are less efficient for in vitro fertilization26 (Fig. 1B). When we compared the effect of a short pulse of Ca2+ ionophore on sperm from CD1 (ICR) with sperm from C57BL/6J mice, A23187 treatment elevated the percentage of hyperactive C57BL/6J sperm to similar levels as those obtained using CD1 (ICR) sperm (Fig. 1A). Moreover, this increase was followed by a significant increase in C57BL/6J sperm fertilization rate (Fig. 1B). Importantly, treating C57BL/6J sperm with a pulse of A23187 increased the percentage of 2-cell embryos competent to develop into blastocysts (Fig. 1C,D). Capacitation requires PKA activation19 and, as expected, in the presence of the PKA inhibitor H89, C57BL/6J sperm were unable to fertilize in vitro (Fig. 1E) and did not show the prototypical increase in phosphorylation of PKA substrates (Fig. 1F). Remarkably, as seen previously with CD1 (ICR) sperm23, incubating H89-treated C57BL/6J sperm for 10 min with A23187 was sufficient to induce fertilizing capacity (Fig. 1E), despite the fact that PKA remained inactive (Fig. 1F). Altogether, these data indicate that transient exposure to A23187 can improve IVF success for mouse strains with reduced fertility, in a PKA independent manner.

A23187 improves hyperactivation and fertilizing capacity of sperm from C57BL/6J genetic background.

Sperm from CD1 (ICR) or C57BL/6J mice were treated with or without 20 μM A23187 for 10 min as described in Methods. After capacitation, sperm parameters were measured. In each of the panels, bars represent average ± SEM (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001) from independent experiments as indicated below. (A) Hyperactivation. The percentage of hyperactive motile sperm was obtained using CASAnova software (n = 4). (B) IVF. Fertilization rate was calculated considering the percentage of inseminated eggs achieving two-cell stage (n = 7). (C) Percentage of blastocyst formation. After 24 hours incubation, 2-cell embryos were transferred to KSOM media and incubated for additional 2.5 days to reach blastocyst stage. Notice that the percentage of blastocysts formation presented in the figure was obtained considering only the total 2-cell embryos and not the original number of oocytes. (D) Example of blastocysts formed using C57BL/6J sperm without (left panel) or with A23187 pre-treatment (right panel). (E) IVF conducted in the presence of H89 inhibitor. Sperm treated or not with A23187 for 10 min were incubated in the absence or in the presence of 50 μM H89. Fertilization rate was calculated as in B. (F) A23187 treatment overcomes the need for PKA activation in spermatozoa. Sperm treated or not with A23187 as described above were incubated in the absence or in the presence of 50 μM H89. Western blots were conducted as described in Methods (n = 3).

A23187 treatment rescues hyperactivation and fertilizing capacity of CatSper1 KO sperm

In the absence of the CatSper channel complex, sperm fail to undergo hyperactivated motility and are unable to fertilize24. To test whether Ca2+ ionophore treatment can overcome the CatSper infertile phenotype, sperm from CatSper1 KO mice were incubated in conditions that support capacitation in the absence or in the presence of 20 μM A23187. After 10 min, the sperm were washed twice by centrifugation in A23187-free media and the percentage of hyperactive sperm was measured using CASA. As expected, in the absence of A23187, CatSper KO sperm did not undergo hyperactivation (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Table II and Supplementary Movie 1). However, once exposed to Ca2+ ionophore, a significant number of CatSper KO sperm exhibited hyperactivated motility (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Table II and Supplementary Movie 2). In addition, A23187-treated CatSper KO sperm were competent to fertilize metaphase II-arrested eggs in vitro (Fig. 2B). In two independent experiments, fertilized eggs were allowed to develop to late morula or blastocyst stage (Fig. 2C, left panel) and ten embryos in each case were non-surgically transferred to pseudopregnant WT female mice28,29,30. From these experiments, five CatSper (+/−) mouse pups were born from two different females (Fig. 2C, right panel). These heterozygous F1 mice were fertile; mating a male and female from this heterozygous population yielded a normal litter with 1 wild type, 4 heterozygous and 3 CatSper KO F2 progeny (Fig. 2D).

A23187 treatment induces hyperactivation and fertilizing capacity of CatSper1 KO sperm.

Mouse sperm from CatSper WT and KO were incubated in TYH medium in the presence or absence of A23187 as described above. In each of the panels, bars represent average ± SEM (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001) from 7 independent experiments. (A) Hyperactivation was measured in sperm from WT and CatSper1−/− treated or not with a short (10 min) exposure to 20 μM A23187. After 1 hour and 20 minutes, sperm motility parameters were analyzed by CASA. (B) Approximately 1 × 106 sperm cells from WT and KO CatSper were co-incubated with about 20–30 oocytes. Fertilization rate was scored 24 hour post-insemination as described above. (C) Two cell embryos from IVF were transferred to KSOM media and cultured for 2.5 more days until they reach late morula and early blastocyst (left panel). Then, blastocysts were non-surgically transferred to pseudo-pregnant females. 21 days later pups where born and reared to sexual maturity (right panel). (D) One heterozygous female and one heterozygous male were mated and 8 F2 pups were born. The respective genotype from WT, F1, CatSper−/− and F2 generations were analyzed by PCR.

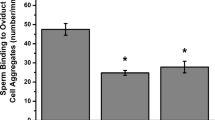

A23187 treatment rescues hyperactivation and fertilizing capacity in sperm of Adcy10 (aka sAC) KO and Slo3 KO but not in sperm from Pmca4 KO mice

Capacitation requires up-regulation of cAMP concentrations18,19 and hyperpolarization of the sperm plasma membrane21. Under normal capacitation conditions, neither sAC KO nor SLO3 KO sperm undergo hyperactivation (Fig. 3B) and while SLO3 KO sperm are able to move (Supplementary Table III and Supplementary Movie 3), sAC KO sperm are almost immotile (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Table III and Supplementary Movie 5). Considering that transient exposure to A23187 can improve IVF success in a PKA independent manner (Fig. 1E and ref. 23), we tested whether these KO mouse models could be rescued by a Ca2+ ionophore pulse. When treated with A23187 for 10 min, a significant fraction of sAC KO sperm became motile and both sAC KO and SLO3 KO sperm underwent hyperactivation (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Movies 4 and 6). Moreover, A23187 treatment induced in vitro fertilizing capacity in sperm from both KO models (Fig. 3C).

A23187 treatment induces fertilizing capacity in sperm from Adcy10 and Slo3 infertile KO genetic models but not in sperm from Pmca4 KO.

Sperm from 3 different KO genetic mice models with their respective WT were incubated in TYH standard in the presence or absence of A23187 as describe above. In each of the panels, bars represent average ± SEM (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001) from 7 WT (C57BL/6J), 3 Slo3 KO and 4 Adcy10 KO (aka sAC) independent experiments. (A) The percentage of motile sperm was measured by CASA system from WT (C57BL/6J), Slo3 KO and Adcy10 KO (aka Sac) at time 1 hour and 20 min after A23187 treatment (10 min A23187 exposure). (B) Hyperactivation rate was measured at the same time by analysis of sperm motility parameters using CASAnova software. (C) Fertilization rate was scored 24 hour post-insemination as described above. (D,E) Analysis of sperm functional parameters in Pmca4−/−. Hyperactivation (D) and fertilization rate (E) were measured as above with sperm were pre-treated or not with A23187 for 10 min.

We previously showed that the increase in intracellular Ca2+ caused by A23187 has to be followed by a reduction in intracellular concentrations of this ion after removal of the ionophore23. In sperm, two molecules are thought to mediate Ca2+ extrusion, namely the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and the more efficient, sperm-specific Ca2+ ATPase PMCA431. Male Pmca4 KO mice are infertile32; their sperm display poor motility and do not undergo hyperactivation (Fig. 3D,E). These data suggest this molecule is involved in regulation of normal Ca2+ homeostasis in sperm. We hypothesized that sperm lacking PMCA4 would have diminished capacity to efflux Ca2+ following ionophore treatment and be less susceptible to A23187 rescue. Treatment with A23187 rendered all Pmca4−/− sperm motionless and their motility was not recovered after ionophore removal (Fig. 3D). Consequently, neither their hyperactivated motility nor their fertilizing capacity was rescued (Fig. 3E).

Discussion

Capacitation encompasses a series of sequential and concomitant biochemical changes required for sperm to gain full fertilization competency. Despite the relevance of capacitation, the molecular mechanisms intrinsic to this process are not well understood. A very early event in sperm capacitation is the activation of motility by a cAMP-dependent pathway33. The activation of cAMP synthesis occurs immediately after sperm are released from the epididymis and come into contact with high HCO3− and Ca2+ present in the seminal fluid34,35. Plasma membrane transport of these ions regulates sperm cAMP metabolism through stimulation of Adcy10 (aka sAC)18, which elevates intracellular cAMP and activates PKA. Then, PKA phosphorylates target proteins and initiates several signaling pathways. These pathways include sperm plasma membrane hyperpolarization, increase in pHi and increase in intracellular Ca2+ ions. Consistent with the influence of these events, KO mice models in which any of these pathways is interrupted are infertile.

Physiologically, sperm capacitation is associated with preparation for a physiological acrosome reaction and changes in their motility pattern collectively known as hyperactivation. Originally observed in hamster sperm moving in the oviduct, hyperactivated motility36 was later described in other mammalian species including humans37. Hyperactivation is associated with a strong, high-amplitude asymmetrical flagellar beating that appears to be essential for the sperm to loosen their attachment to the oviductal epithelium and to penetrate the zona pellucida38. Consistent with an essential role of hyperactivation for fertilization competency, low motility and/or defects in hyperactivation is one of the most common phenotypes observed in sperm from many different infertile knock-out models, including those used in the present work (i.e., Catsper−/−, Adcy10−/−, Slo3−/− and Pmca4−/−)18,21,24,32.

Although very little is known about the molecular pathways regulating hyperactivation, Ca2+ ions have been shown to play roles in the initiation and maintenance of this type of movement22. Most of the information regarding the role of Ca2+ in hyperactivation has been obtained using loss-of-function approaches analyzing sperm motility in media devoid of Ca2+ ions. Gain-of-function experiments using Ca2+ ionophores (e.g. A23187, ionomycin) to increase [Ca2+]i have yielded unexpected results because, instead of enhancing hyperactivation, these compounds stopped sperm movement7,23,39. Despite being motionless, ionophore-treated sperm are alive as they recover motility after the compound is quenched with lipophilic agents39 or removed by centrifugation23. The reversibility of the A23187 effect suggests that the sperm is able to return to physiological [Ca2+]i after a drop in free ionophore concentration. In our previous work, we showed that a short incubation period with A23187, in addition to initiating hyperactivation, accelerated the acquisition of fertilizing capacity. Most importantly, our data indicated that 10 min incubation with A23187 induced fertilization competence even when activation of cAMP-dependent signaling pathways was blocked23.

Considering these results, we hypothesized that a temporary elevation of intracellular Ca2+ primes the sperm for hyperactivation and bypasses the need for other signaling pathways required to up-regulate Ca2+ influx in sperm. To test this hypothesis, in the present work, we selected four KO models affecting independent signaling pathways involved in sperm motility. Three of these signaling molecules are believed to act upstream of the increase in Ca2+ required for hyperactivation: CatSper, sAC and SLO3. Sperm from each of these mouse models were unable to undergo hyperactivation and are incapable of fertilizing metaphase II arrested eggs in vitro. In addition, Pmca4 KO sperm were used, which would not allow intracellular Ca2+ lowering after saturating sperm cells with this ion. Pmca4 KO mice are sterile because their sperm are deficient in both progressive and hyperactivated motility25,40. PMCA4 has been shown to be an essential source of Ca2+ clearance in sperm and it is required to achieve a low resting [Ca2+]i31. Consistent with our hypotheses, a short incubation of sperm with A23187 induced hyperactivation of CatSper, Adcy10 and Slo3 KO but not of Pmca4 KO sperm.

Male factors contribute to approximately half of all cases of infertility41. However, in over 75% of these cases it is unusual to have a clear diagnosis of the abnormalities found in semen parameters42,43. Currently, assisted reproductive technologies (ART) remain the main therapy available. Recent studies using KO mouse models, including those used in the present work, revealed that loss of function of a variety of genes results in infertility. Interestingly, several of these models display normal sperm counts and their main deficiency is found in capacitation-associated processes such as impediments to undergo hyperactivation24, to undergo the acrosome reaction21, or to go through the utero-tubal junction in vivo44,45. We hypothesize that strategies designed to elevate [Ca2+]i such as the use of A23187 pulse should overcome the need of upstream signaling pathways including but not limited to PKA activation. In addition, although IVF has been successfully employed in multiple species5, requirements of sperm for capacitation vary greatly among species and have been developed for each sperm type essentially by trial and error. In some species, such as the horse, effective methods for IVF have yet to be established despite decades of work46. Failure of equine IVF does not appear to be associated with oocyte characteristics47 but with the inability of horse sperm to hyperactivate and to penetrate the egg zona pellucida (ZP), two landmarks of capacitation. A better understanding of capacitation signaling processes have the potential to generate a “universal” IVF technology that can be used in endangered/exotic species for which ART is not currently available.

Improving IVF conditions would be of great value; however, at the clinical level, ICSI has replaced IVF when confronted with cases of infertility due to unknown male factor(s). ICSI is reliable and, from the patient’s point of view, more economical because of higher probability of success. Despite these advantages, ICSI bypasses certain aspects of normal fertilization and may bear effects that are not easily observed. Taking this into consideration, a method to improve IVF can be a desirable option in some male factor cases. It is worth noting that A23187 has already been used in the clinic for patients with repeated ICSI failure48 due to problems in egg activation. In these cases, fertilized eggs are transiently incubated with ionophore after ICSI, which exposes the zygote to high Ca2+. On the contrary, with the method described here, where sperm are transiently treated with A23187, the ionophore is washed out and does not come in contact with the embryo. More interestingly, using this methodology to overcome infertility problems related to motility and hyperactivation could be used to improve the success rate of intrauterine insemination, which is a significantly less invasive and less costly procedure than either IVF or ICSI.

Methods

Materials

Chemicals and other lab reagents were purchased as follows: Calcium Ionophore A23187 (C7522), Bovine serum albumin (BSA, fatty acid-free) (A0281), Tween-20 (P7949), fish skin gelatin (G7765), Pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (G4877) and human chorionic gonadotropin (CG5), were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Non-Surgical Embryo Transfer (NSET) Device was acquired from Paratechs (Billerica, MA). N-[2-[[3-(4-bromophenyl)-2-propen-1-yl]amino]ethyl]5-isoquinolinesulfonamide and dihydrochloride H-89 (130964-39-5) were purchased from Cayman chemical (Ann Arbor, Michigan). Embryo transfer light mineral oil (ES-005-C) and EmbryoMax® KSOM Medium (1X) w/1/2 Amino Acids (MR-106-D) were obtained from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Rabbit monoclonal anti-phosphoPKA substrates (anti-pPKAS) (clone100G7E), was purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgGs was purchased from Jackson Immuno-Research Laboratories GE Life Sciences. 30% Acrylamide and β-Mercaptoethanol were obtained from Biorad.

Animals

All procedures (including euthanasia, embryo transfer and genotyping) involving experimental animals were performed in accordance with Protocol #2013-0020 approved by the University of Massachusetts-Amherst Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). CD1 (ICR) mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Infertile KO mice genetic models (CatSper KO24, Slo3 KO21, Adcy10 KO18) and their corresponding wild type were on an C57BL/6J background; Pmca4−/− 32 mice and corresponding wild type were on an FVB/N background. These genetically modified mice models as well as their wild type siblings were either provided by authors of this manuscript (Dr. Levin and Dr. Buck for Adcy10−/−; Dr. Celia Santi for SLO3 KO; Dr. Patricia Martin-De Leon for PMCA4 KO) or donated (CatSper KO mice were donated by Dr. David Clapham). Three of these lines can also be obtained as cryopreserved embryos. The respective strain, stock number and respective website information are: Adcy10 KO: B6;129S5-Adcy10tm1Lex/Mmnc; Stock number: 011659-UNC (https://www.mmrrc.org/catalog/sds.php?mmrrc_id=11659). CatSper1 KO: B6.129S4-Catsper1tm1Clph/J; stock number: 018311 (https://www.jax.org/strain/018311). PMCA4 KO: Atp2b4 nulls, MMRRC; Stock No: 36807-JAX (https://www.mmrrc.org/catalog/sds.php?mmrrc_id=36807). For CatSper embryo recipients, surrogate mothers were CD1 (ICR) females, 8–12 weeks of age. In experiments in which phosphorylation by PKA was investigated, C57BL/6J male mice were used. Vasectomized males were obtained from Charles River and used to induce pseudopregnancy as previously described49.Non-surgical embryo transfer (NSET) was performed with an NSET device (ParaTechs, Lexington, KY)29,30.

Media

Medium used for sperm capacitation and fertilization assays was Toyoda–Yokoyama–Hosi (standard TYH) medium50, containing 119.37 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.71 mM CaCl2.2H2O, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4.7H2O, 25.1 mM NaHCO3−, 0.51 mM Na-pyruvate, 5.56 mM glucose and 4 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA), 10 μg/mL Gentamicin and phenol red 0.0006% at pH 7.4 equilibrated with 5% CO2. For capacitating conditions Ca2+ ionophore A23187 was used at a final concentration of 20 μM in TYH as previously described23.

Mouse Sperm Preparation

Cauda spermatozoa were collected from each of the mouse strains described above. Each cauda epididymis was placed in 500 μL of TYH media. After 10 min. incubation at 37 °C (swim-out), epididymis tissue debris were removed and the suspension adjusted to a final concentration of 1–2 107 cells/ml and divided into two aliquots. Aliquots were supplemented with either 20 μM A23187 or equivalent quantities of DMSO (for controls) and further incubated at 37 °C. After 10 min. incubation, sperm were washed with 2 rounds of centrifugations (first one at 500 × g and the second one at 300 × g for 5 min each) in A23187-free TYH medium. Sperm were then re-suspended in A23187-free TYH and capacitated in CO2 incubator for an additional hour and 20 min. To evaluate sperm in conditions in which PKA is inactivated, H89 was used at a concentration of 50 μM for all incubation periods including those used for washing the ionophore A23187. After capacitation in each condition, sperm were used for the analysis of phosphorylated PKA substrates, hyperactivation and fertilizing capacity (see below).

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblotting

After 1 hour and 20 min incubation in each condition, sperm proteins were extracted for Western blot analysis as previously described22. Protein extracts equivalent to 1 × 106 sperm were loaded per line and subjected to SDS-PAGE an electro-transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad) at 250 mA for 90 min on ice. To analyze phosphorylated PKA substrates, anti-phosphoPKA substrate (anti-pPKAS) (1/10000) Western blots were used as described22.

Hyperactive and Motility Parameters

Sperm suspensions (25 μl) were loaded into one pre-warmed chamber slide (depth, 100 μm) (Leja slide, Spectrum Technologies) and placed on a microscope stage at 37 °C. Sperm movements were examined using the CEROS computer-assisted semen analysis (CASA) system (Hamilton Thorne Research, Beverly, MA). The default settings include the following: frames acquired: 90; frame rate: 60 Hz; minimum cell size: 4 pixels; static head size: 0.13–2.43; static head intensity: 0.10–1.52; static head elongation: 5–100. Sperm with hyper activated motility, defined as motility with high amplitude thrashing patterns and short distance of travel, were sorted and analyzed using the CASAnova software27. At least 20 microscopy fields corresponding to a minimum of 200 sperm were analyzed in each experiment.

Sperm Motility Video Recordings

Sperm suspensions (25 μl) were loaded into one pre-warmed chamber slide (depth, 100 μm) (Leja slide, Spectrum Technologies). Videos were recorded for 15 seconds using an Andor Zyla microscope camera (Belfast, Northern Ireland) mounted on Nikon TE300 inverted microscope (Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan) fitted with 20 times objective lenses. Sample temperatures were maintained at 37 °C using a Warm Stage (Frank E. Fryer scientific instruments, Carpentersville, Illinois).

Mouse eggs collection and IVF assays

Metaphase II-arrested mouse eggs were collected from 6–8 week-old super ovulated CD1 (ICR) female mice (Charles River Laboratories) as previously described22. Females were each injected with 5–10 IU equine chorionic gonadotropin and 5–10 IU human chorionic gonadotropin 48 h apart. The cumulus-oocyte complexes (COC’s) were placed into a well with 500 μl of media (TYH standard medium) previously equilibrated in an incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Fertilization wells containing 20–30 eggs were inseminated with sperm incubated as described above in medium supporting capacitation with or without A23187 treatment (final concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml). After 4 h of insemination, eggs were washed and put in fresh media. The eggs were evaluated 24 h post-insemination. To assess fertilization the three following criteria were considered: 1) the formation of the male and female pronuclei; 2) the emission of the second polar body; and 3) two-cells stages.

Embryo Culture, Embryo transfer and Mice Genotyping

Twenty-four hours post-insemination, fertilized 2 cell embryos were transferred to drops containing KSOM media and further incubated between 3.5 and 4.1 days. At this stage, the percentage of blastocyst formation was evaluated. In some cases, 10 to 20 blastocysts were transferred to 2.5 days post coitum (dpc) pseudo-pregnant CD-1 recipient females using the non-surgical uterine embryo transfer device28. Pseudo-pregnant CD-1 recipient females were obtained by mating with vasectomized males (obtained from Charles River) one day after in vitro fertilization. Only females with a clear plug were chosen as embryo recipients; late morula and early stage blastocysts were chosen to be transferred. Routine genotyping was performed with total DNA from tail biopsy samples from weaning age pups as templates for PCR using genotyping primers for CatSper gene forward [5′-TAAGGACAGTGACCCCAAGG-3′] and reverse [5′-TAAGGACAGTGACCCCAAGG-3′] and for the reporter gene Lacz forward [5′TGATTAGCGCCGTGGCCTGATTCATTC-3′] and reverse [5′-AGCATCATCCTCTGCATGGTCAGGTC-3′] as described by the original authors24.

Statistical analysis

Data from all studies are analyzed using SIGMA plot software (www.sigmaplot.com). Data are expressed as the means ± S.E.M. The difference between mean values of multiple groups was analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s test. Statistical significances are indicated in the Figure legends.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Navarrete, F. A. et al. Transient exposure to calcium ionophore enables in vitro fertilization in sterile mouse models. Sci. Rep. 6, 33589; doi: 10.1038/srep33589 (2016).

References

Steptoe, P. C. & Edwards, R. G. Birth after the reimplantation of a human embryo. Lancet 2, 366 (1978).

Chang, M. C. Fertilizing capacity of spermatozoa deposited into the fallopian tubes. Nature 168, 697–698 (1951).

Austin, C. R. Observations on the penetration of the sperm in the mammalian egg. Australian journal of scientific research Ser B: Biological sciences 4, 581–596 (1951).

Visconti, P. E., Krapf, D., de la Vega-Beltran, J. L., Acevedo, J. J. & Darszon, A. Ion channels, phosphorylation and mammalian sperm capacitation. Asian J Androl 13, 395–405 (2011).

Yanagimachi, R. Mammalian fertilization. In: The Physiology of Reproduction (ed^(eds Knobil, E. & Neill, J. D. ). Raven Press, Ltd. (1994).

Visconti, P. E. et al. Capacitation of mouse spermatozoa. II. Protein tyrosine phosphorylation and capacitation are regulated by a cAMP-dependent pathway. Development 121, 1139–1150 (1995).

Visconti, P. E. et al. Roles of bicarbonate, cAMP and protein tyrosine phosphorylation on capacitation and the spontaneous acrosome reaction of hamster sperm. Biol Reprod 61, 76–84 (1999).

Gadella, B. M. & Harrison, R. A. The capacitating agent bicarbonate induces protein kinase A-dependent changes in phospholipid transbilayer behavior in the sperm plasma membrane. Development 127, 2407–2420 (2000).

Zeng, Y., Oberdorf, J. A. & Florman, H. M. pH regulation in mouse sperm: identification of Na(+)-, Cl(−)- and HCO3(−)-dependent and arylaminobenzoate-dependent regulatory mechanisms and characterization of their roles in sperm capacitation. Dev Biol 173, 510–520 (1996).

Zeng, Y., Clark, E. N. & Florman, H. M. Sperm membrane potential: hyperpolarization during capacitation regulates zona pellucida-dependent acrosomal secretion. Dev Biol 171, 554–563 (1995).

Escoffier, J., Krapf, D., Navarrete, F., Darszon, A. & Visconti, P. E. Flow cytometry analysis reveals a decrease in intracellular sodium during sperm capacitation. J Cell Sci 125, 473–485 (2012).

de La Vega-Beltran, J. L. et al. Mouse sperm membrane potential hyperpolarization is necessary and sufficient to prepare sperm for the acrosome reaction. J Biol Chem In Press (2012).

Ruknudin, A. & Silver, I. A. Ca2+ uptake during capacitation of mouse spermatozoa and the effect of an anion transport inhibitor on Ca2+ uptake. Mol Reprod Dev 26, 63–68 (1990).

Visconti, P. E., Bailey, J. L., Moore, G. D., Pan, D., Olds-Clarke, P. & Kopf, G. S. Capacitation of mouse spermatozoa. I. Correlation between the capacitation state and protein tyrosine phosphorylation. Development 121, 1129–1137 (1995).

Krapf, D. et al. Inhibition of Ser/Thr phosphatases induces capacitation-associated signaling in the presence of Src kinase inhibitors. J Biol Chem 285, 7977–7985 (2010).

Esposito, G. et al. Mice deficient for soluble adenylyl cyclase are infertile because of a severe sperm-motility defect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101, 2993–2998 (2004).

Steegborn, C., Litvin, T. N., Levin, L. R., Buck, J. & Wu, H. Bicarbonate activation of adenylyl cyclase via promotion of catalytic active site closure and metal recruitment. Nature structural & molecular biology 12, 32–37 (2005).

Hess, K. C. et al. The “soluble” adenylyl cyclase in sperm mediates multiple signaling events required for fertilization. Dev Cell 9, 249–259 (2005).

Nolan, M. A., Babcock, D. F., Wennemuth, G., Brown, W., Burton, K. A. & McKnight, G. S. Sperm-specific protein kinase A catalytic subunit Calpha2 orchestrates cAMP signaling for male fertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101, 13483–13488 (2004).

De La Vega-Beltran, J. L. et al. Mouse sperm membrane potential hyperpolarization is necessary and sufficient to prepare sperm for the acrosome reaction. J Biol Chem 287, 44384–44393 (2012).

Santi, C. M. et al. The SLO3 sperm-specific potassium channel plays a vital role in male fertility. FEBS Lett 584, 1041–1046 (2010).

Navarrete, F. A. et al. Biphasic Role of Calcium in Mouse Sperm Capacitation Signaling Pathways. J Cell Physiol (2015).

Tateno, H. et al. Ca2+ ionophore A23187 can make mouse spermatozoa capable of fertilizing in vitro without activation of cAMP-dependent phosphorylation pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110, 18543–18548 (2013).

Ren, D. et al. A sperm ion channel required for sperm motility and male fertility. Nature 413, 603–609 (2001).

Okunade, G. W. et al. Targeted ablation of plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) 1 and 4 indicates a major housekeeping function for PMCA1 and a critical role in hyperactivated sperm motility and male fertility for PMCA4. J Biol Chem 279, 33742–33750 (2004).

Liu, L., Nutter, L. M., Law, N. & McKerlie, C. Sperm freezing and in vitro fertilization in three substrains of C57BL/6 mice. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 48, 39–43 (2009).

Goodson, S. G., Zhang, Z., Tsuruta, J. K., Wang, W. & O’Brien, D. A. Classification of mouse sperm motility patterns using an automated multiclass support vector machines model. Biol Reprod 84, 1207–1215 (2011).

Bin Ali, R. et al. Improved pregnancy and birth rates with routine application of nonsurgical embryo transfer. Transgenic Res 23, 691–695 (2014).

Steele, K. H., Hester, J. M., Stone, B. J., Carrico, K. M., Spear, B. T. & Fath-Goodin, A. Nonsurgical embryo transfer device compared with surgery for embryo transfer in mice. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 52, 17–21 (2013).

Stone, B. J., Steele, K. H. & Fath-Goodin, A. A rapid and effective nonsurgical artificial insemination protocol using the NSET device for sperm transfer in mice without anesthesia. Transgenic Res 24, 775–781 (2015).

Wennemuth, G., Babcock, D. F. & Hille, B. Calcium clearance mechanisms of mouse sperm. J Gen Physiol 122, 115–128 (2003).

Prasad, V., Okunade, G. W., Miller, M. L. & Shull, G. E. Phenotypes of SERCA and PMCA knockout mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 322, 1192–1203 (2004).

Buffone, M. G., Wertheimer, E. V., Visconti, P. E. & Krapf, D. Central role of soluble adenylyl cyclase and cAMP in sperm physiology. Biochim Biophys Acta 1842, 2610–2620 (2014).

Wennemuth, G., Carlson, A. E., Harper, A. J. & Babcock, D. F. Bicarbonate actions on flagellar and Ca2+-channel responses: initial events in sperm activation. Development 130, 1317–1326 (2003).

Carlson, A. E., Quill, T. A., Westenbroek, R. E., Schuh, S. M., Hille, B. & Babcock, D. F. Identical phenotypes of CatSper1 and CatSper2 null sperm. J Biol Chem 280, 32238–32244 (2005).

Yanagimachi, R. The movement of golden hamster spermatozoa before and after capacitation. J Reprod Fertil 23, 193–196 (1970).

Burkman, L. J. Characterization of Hyperactivated Motility by Human-Spermatozoa during Capacitation-Comparison of Fertile and Oligozoospermic Sperm Populations. Arch Andrology 13, 153–165 (1984).

Suarez, S. S. & Osman, R. A. Initiation of hyperactivated flagellar bending in mouse sperm within the female reproductive tract. Biol Reprod 36, 1191–1198 (1987).

Suarez, S. S., Vincenti, L. & Ceglia, M. W. Hyperactivated motility induced in mouse sperm by calcium ionophore A23187 is reversible. J Exp Zool 244, 331–336 (1987).

Schuh, K. et al. Plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase 4 is required for sperm motility and male fertility. J Biol Chem 279, 28220–28226 (2004).

Martinez, G., Daniels, K. & Chandra, A. Fertility of men and women aged 15–44 years in the United States: National Survey of Family Growth, 2006–2010. Natl Health Stat Report 1–28 (2012).

Brown, S. G. et al. Depolarization of sperm membrane potential is a common feature of men with subfertility and is associated with low fertilization rate at IVF. Hum Reprod (2016).

Williams, H. L. et al. Specific loss of CatSper function is sufficient to compromise fertilizing capacity of human spermatozoa. Hum Reprod 30, 2737–2746 (2015).

Coy, P., Garcia-Vazquez, F. A., Visconti, P. E. & Aviles, M. Roles of the oviduct in mammalian fertilization. Reproduction 144, 649–660 (2012).

Tokuhiro, K., Ikawa, M., Benham, A. M. & Okabe, M. Protein disulfide isomerase homolog PDILT is required for quality control of sperm membrane protein ADAM3 and male fertility [corrected]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 3850–3855 (2012).

Hinrichs, K. Assisted reproduction techniques in the horse. Reproduction, Fertility and Development 25, 80–93 (2013).

Hinrichs, K., Love, C. C., Brinsko, S. P., Choi, Y. H. & Varner, D. D. In vitro fertilization of in vitro-matured equine oocytes: effect of maturation medium, duration of maturation and sperm calcium ionophore treatment and comparison with rates of fertilization in vivo after oviductal transfer. Biol Reprod 67, 256–262 (2002).

Nikiforaki, D. et al. Effect of two assisted oocyte activation protocols used to overcome fertilization failure on the activation potential and calcium releasing pattern. Fertil Steril 105, 798–806 e792 (2016).

Watanabe, H., Kusakabe, H., Mori, H., Yanagimachi, R. & Tateno, H. Production of offspring after sperm chromosome screening: an experiment using the mouse model. Hum Reprod 28, 531–537 (2013).

Toyoda, Y. Y. M. & Hosi, T. Studies on the fertilization of mouse eggs in vitro. The Japanese Journal of Animal Reproduction 16, 147–157 (1971).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants HD38082 and HD44044 (to P.E.V.); GM107442 and HD059913 (to L.R.L. and J.B.); 1R21HD078942-01A1 (to J.M.); HD051872 (to R.A.F.); R01HD069631 (to C.M.S.); RO3HD073523 (to P.M.-D.L.); and DGAPA/UNAM (IN205516 to A.D.). The authors would like to thank Dr. Jean-Ju Chung and Dr. David Clapham who kindly donated the catsper1−/− mice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.A.N., A.D. and P.E.V. were responsible for the organization and design of the whole work, data analysis and preparation of manuscript; F.A.N. and H.C.L. performed the IVF experiments; F.A.N. and A.A. performed the Computer Assisted Sperm analysis; F.A.N. performed the embryo culture, embryo transfers and genotyping; A.M.S., D.K., L.R.L., J.B., C.M.S., P.M.-D.L., J.M. and R.A.F. contributed with experimental design, animal protocols, discussion of findings and correction of manuscript. All authors contributed specific parts of the manuscript, with P.E.V., A.D. and F.A.N. assuming responsibility for the manuscript in its entirety.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Drs Levin and Buck report owning equity interest in CEP Biotech which has licensed commercialization of a panel of monoclonal antibodies directed against sAC. All other author(s) declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Navarrete, F., Alvau, A., Lee, H. et al. Transient exposure to calcium ionophore enables in vitro fertilization in sterile mouse models. Sci Rep 6, 33589 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep33589

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep33589

This article is cited by

-

Advances in the study of genetic factors and clinical interventions for fertilization failure

Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics (2023)

-

Sperm ion channels and transporters in male fertility and infertility

Nature Reviews Urology (2021)

-

Chromatin Protamination and Catsper Expression in Spermatozoa Predict Clinical Outcomes after Assisted Reproduction Programs

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.