Abstract

Nonsyndromic Cleft Lip and/or Palate (NSCLP) is regarded as a multifactorial condition in which clefting is an isolated phenotype, distinguished from the largely monogenic, syndromic forms which include clefts among a spectrum of phenotypes. Nonsyndromic clefting has been shown to arise through complex interactions between genetic and environmental factors. However, there is increasing evidence that the broad NSCLP classification may include a proportion of cases showing familial patterns of inheritance and contain highly penetrant deleterious variation in specific genes. Through exome sequencing of multi-case families ascertained in Bogota, Colombia, we identify 28 non-synonymous single nucleotide variants that are considered damaging by at least one predictive score. We discuss the functional impact of candidate variants identified. In one family we find a coding variant in the MSX1 gene which is predicted damaging by multiple scores. This variant is in exon 2, a highly conserved region of the gene. Previous sequencing has suggested that mutations in MSX1 may account for ~2% of NSCLP. Our analysis further supports evidence that a proportion of NSCLP cases arise through monogenic coding mutations, though further work is required to unravel the complex interplay of genetics and environment involved in facial clefting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cleft lip and/or palate (CLP) phenotypes are among the most frequent birth defects occurring at rates of 1/500–1/2500 births1. A proportion of cases present with syndromic disease (CLP in addition to a spectrum of additional phenotypes) mostly caused by rare mutations in single genes that often show Mendelian patterns of inheritance. However up to 70% of cases show phenotypes lacking any additional cognitive or craniofacial abnormalities, referred to as nonsyndromic cleft lip and/or palate (NSCLP). Such phenotypes are regarded as genetically complex arising through the interplay of numerous genetic and environmental factors. Increased understanding of the underlying aetiology of NSCLP phenotypes (both genetic and environmental) is needed to ultimately develop strategies for prevention and improve treatment and prognosis. NSCLP has a significant genetic basis, for example, the first degree relatives of affected individuals have a 30–40 fold elevated risk and phenotype concordance for monozygotic (MZ) twins is 40–60%, compared to 5% for di-zygotic twins1. Genetic studies including linkage analysis, genome-wide association (GWAS) and GWAS-based meta-analysis, have yielded reproducible evidence for the involvement of several genes and gene regions. Collins et al.2, listed 16 genes and gene regions which have been firmly implicated in NSCLP through linkage and association analysis. Several of these are broad regions where the underlying causal variant(s) have yet to be pinpointed, however, polymorphisms in genes such as IRF6 are strongly associated with NSCLP3 and more minor roles have been established for MSX14,5, PVRL1, FGFR2, PAX7, NOG and SPRY2 among others6.

Exome sequencing presents opportunities to identify rare coding variation that may contribute to risk of NSCLP phenotypes. If NSCLP is entirely multifactorial, the contribution of rarer variants may be largely polygenic and mediated by numerous variants of very small individual effect. In this case, causal genes may only be detectible through the analysis of large numbers of patients using, for example, burden tests7. However, there is growing evidence for involvement of rare variants of larger effect in NSCLP including, for example, truncating mutations in the ARHGAP29 gene8 and mutations in the IRF6 gene, which is also known to contain mutations involved in malformation syndromes that include CLP such as Van der Woude9. We consider here a number of NSCLP families with multiple affected individuals and undertake exome sequencing to investigate the contribution of rare variants in genes previously associated with any form of clefting phenotype.

Materials and Methods

Exome sequences of twelve individuals from seven multi-case families (CL1-CL7) with NSCLP phenotypes were obtained. All experimental protocols were approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the Universidad de La Sabana, Bogota; informed consent was obtained for all participants and research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Families included between two and six individuals with isolated NSCLP (Fig. 1). Most individuals have unilateral CLP but several individuals have the more severe bilateral phenotype.

DNA samples were extracted from blood collected at Operation Smile, Bogota, Colombia and exomes were captured using the Agilent SureSelect v5 (51 Mb) kit and sequenced on a HiSeq 2000. Read depth coverage statistics for all 12 exome sequences are given in Supplementary Table 1 and indicate ~85–97% coverage of exon targets at >20 fold depth across all samples. Orthogonal genotyping was performed for a panel of 24 SNPs to validate sample identity after processing10.

To understand the spectrum of potentially damaging variation, we considered the list of 865 genes previously implicated in any form of CLP phenotype presented by Pengelly et al.11 (Supplementary Table 2). Examining rare variation in genes in this comprehensive list enables evaluation of whether known CLP genes contain variation which may underlie more familial forms of NSCLP. Furthermore, because each exome contains a very large number of putatively damaging variants including those completely unrelated to the clefting phenotypes (including potential incidental findings), this strategy focussing only on genes previously implicated in any form of clefting is a practical route to identifying causal variation in these families. The list is derived in part (363 genes out of the 865) from the professional Human Gene Mutation Database12, using search terms related to clefts and clefting syndromes. The remaining genes in the list were included after corresponding interrogation of OMIM13 and a small number of additional CLP-related genes from the review by Collins et al.2.

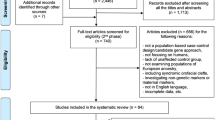

We filtered the lists of variants (Fig. 2) found in the exome sequences to identify all non-synonymous (NS), stopgain, stoploss, splicing and indel variants in genes from this list. Following Pengelly et al.11, for NS variants we used the scaled predictive scores from dbNSFP v214 and considered only variants classed as deleterious or damaging by at least one of the following predictive metrics: PhyloP, SIFT, Polyphen2, LRT, MutationTaster and GERP++. Grantham scores were also assigned to all NS substitutions. All variants were annotated with the minor allele frequency (MAF) from the ExAC database15, combined CADD and Logit scores for deleteriousness, along with a combined overall rank developed from PhylopP, GERP++, CADD and Logit scores based on the summed ranks across all four scores such that a variant with overall rank 1 is predicted as most deleterious. For intronic variants within 10 bp of the exon we utilised MaxEntScan, based upon quantifying deviation from the expected splicing consensus sequence motif, to evaluate the likelihood of this variant affecting splicing, using a cutoff of a differential score of 316.

We excluded variants found in homopolymer/repeat regions that can arise through misalignment between the sequenced reads and reference sequence. Any variants with read depth of <10 or in genes considered to be ‘highly mutable’17 were removed from further consideration. We included all variants not previously listed in the following databases: dbSNP 13518, 1000 genomes19, the exome variant server20 and our in-house database of ~300 exomes, but did not exclude variants present solely at low frequency in the ExAC database15. In Tables 1 & 2 we included only variants found in all exome-sequenced, affected, family members but not shared by more than one family; this was to exclude variants potentially common to the region not captured in the population resequencing projects. Because samples were not available for all family members, it was not possible to confirm segregation of putatively causal variants for all affected individuals. All variants presented in text were manually visualised to evaluate genotype quality in the raw alignment files using IGV21 and no features consistent with errors were present yielding high-confidence genotype calls. The full list of rare (<1% in 1000 Genomes) NS variants classed as damaging by at least one predictive score and potentially damaging splicing variants are given in Supplementary Table 3. Whole-exome genotype calls are provided in Supplementary File 4.

Results

Table 1 shows likely protein truncating and indel variants in these seven families, with Table 2 listing 28 missense variants. For a given family only variants found for all the exome-sequenced family members (Fig. 1) and classed as deleterious by at least one predictive score is given. Table 2 entries are ordered using combined ranks from most to least deleterious by predictive score11. Four of the genes listed in Table 2 (WNT7A, MSX1, CLPTM1 and EVC2, ranked 9, 10, 11 and 23 respectively) have been previously identified as containing variants implicated in NSCLP phenotypes. Family CL1 has the 9th ranked variant in the WNT7A gene. Members of the WNT gene family have previously been associated with NSCLP phenotypes22,23,24. Specifically, a number of WNT signalling pathway genes including WNT3A, WNT5A, WNT9B and WNT11 have been established as candidates22 and mouse expression studies have shown roles for WNT genes in mid-facial formation and lip and palate development25.

The 10th ranked variant, found in family CL4, is in the MSX1 gene and considered damaging by SIFT, PolyPhen-2 and MutationTaster and has high GERP++ and CADD scores. Variants in this gene have been strongly implicated in NSCLP in several studies. Jezewski et al.26 found mutations in 2% of CLP cases and indicated that this has genetic counselling implications where autosomal dominant inheritance patterns are found. Exon 2 of MSX1, in which the p.P260T is located, has been found to be highly conserved with significantly fewer sequence variants compared with exon 1 of this small (two exon) gene26. Functional validation of MSX1 as a candidate is established through a cleft palate and foreshortened maxilla phenotype in knockout mice27. A number of association studies have also indicated involvement of MSX1 in NSCLP4,28,29,30,31. In a study of 94 patients and 93 controls from Operation Smile, Colombia, four MSX1 microsatellite alleles were analysed and an increased risk of CLP was observed with CA polymorphisms in the gene32. An autosomal dominant MSX1 mutation in a family with clefting and tooth agenesis showed a familial pattern of segregating MSX1 mutations5. Diverse evidence establishes that MSX1 promotes growth and inhibits differentiation. Mutations in MSX1 can cause primary or secondary facial clefting in mouse models26.

The 11th ranked variant (from family CL1) is in the CLPTM1 gene (Cleft lip-and palate-associated transmembrane protein-1) which is situated at 19q13.3. A balanced translocation is this region was found in a multi-case CLP family33 and this region is implicated in NSCLP by linkage and transmission disequilibrium test association studies34. However a de novo deletion of 0.8 Mb in this region associated with CLP, but not encompassing CLPTM1, has been reported35. As Kohli and Kohli36 indicate, the role of CLPTM1 or other genes in this locus is uncertain.

The 23rd ranked variant is in the EVC2 gene (family CL2) and belongs to the same two megabase chromosomal region as MSX1 (4p16). Ingersoll et al.37 found linkage and association signals in genes in this region. They found suggestive evidence for linkage and association amongst cleft palate trios to EVC2. Mutations in EVC2 can lead to Weyers acrofacial dysostosis38, not usually associated with oral clefts but cases with subtle CLP phenotypes and tooth anomalies have been reported37.

Discussion

Linkage, candidate gene association and genome-wide association (GWAS) have been applied to investigate numerous multifactorial diseases, including NSCLP. As a result of these studies more than 11 genes and gene regions are now known or likely to have an etiologic role in NSCLP39. However, there is increasing evidence that NSCLP is a heterogeneous condition comprising a substantial multifactorial component along with a much smaller proportion of cases showing more Mendelian patterns of inheritance. The Gajdos et al.40 segregation analysis indicated that the complex familial patterns observed in NSCLP is best explained as a mixture of monogenic cases, probably dominantly inherited, combined with others which have a multifactorial aetiology. The conclusions favour analyses of multiple-case pedigrees to reduce heterogeneity and help identify Mendelian sub-forms. Stanier and Moore41 identified significant overlaps between genes underlying syndromic and nonsyndromic forms of CLP, recognising that several genes implicated in syndromic disease, including TBX22, PVRL1, IRF6, P63 and MSX1, can also contribute to ~10% of NSCLP. Scapoli et al.42 point out that the autosomal dominant Van der Woude syndrome (VWS) is only phenotypically distinguished from NSCLP by lower-lip pits and hypodontia which are only variably present in VWS affected individuals. Mutations in the IRF6 gene, which cause VWS, have been firmly implicated in some NSCLP cases3 supporting heterogeneity with the NSCLP clinical designation. Furthermore, Kerameddin et al.43 found a tag SNP (rs642961) in IRF6 was associated with the most severe complete bilateral NSCLP phenotype. This suggests multi-case families with bilateral clefts are the most likely to be segregating single gene mutations. This strategy is supported by Vieira et al.44 who indicate that point mutations in several genes contribute to ~6% of NSCLP and these are enriched in cases with bilateral clefting.

In Table 2, we identify a coding variant in the MSX1 gene shared by affected family members in CL4 in which the proband has a bilateral CLP phenotype. Direct sequencing of coding regions has shown rare mutations in MSX1 may account for ~2% of NSCLP. The identified MSX1 variant is present at low frequency in the ExAC database (Table 2). ExAC contains >60,000 exomes from various disease specfic and population genetic studies (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/). Functional studies and analyses of larger cohorts of multi-case NSCLP families are required to establish a possible role for this and other rare variants identified in NSCLP phenotypes. Variants identified here also include candidates in the WNT7A (family CL1) ,CLPTM1 (family CL1) and EVC2 genes (family CL2) which should be considered as targets for analysis in additional families.

For investigations aiming to resolve the genetic factors underlying NSCLP in multiple case families, exome sequencing presents a relatively cost-effective approach in which sequencing a small number of affected family members can identify candidate underlying genetic variation. NSCLP provides a particular challenge for genetic studies, with incomplete penetrance and environmental factors hindering the identification of aetiological variance2,39. We have aimed to minimise this effect by careful selection of pedigrees exhibiting clefting in multiple individuals, where we would expect a stronger genetic component. Filtering power would be increased by the inclusion of further members of the pedigrees, however this has not been viable due to the isolated geographic locations for many individuals.

Exome sequencing yields thousands of variants per individual and identification of candidate variants can only be achieved following extensive filtering. We have undertaken filtering to identify variants predicted as damaging by restricting analysis to a list of 865 genes which have been previously associated with any condition involving CLP. Such an approach risks missing causal variants in novel genes not previously linked to NSCLP, but facilitates practicable data interpretation by virtue of the greater prior probability that they are associated with NSCLP. The composite score based rank using PhyloP, GERP++. CADD and logit (Table 2) has been used successfully prioritise variants involved in syndromic CLP11, These four scores are closely correlated, although the composite measures are not independent in every case. Further improvements in predictive tools and recognition of more disease variants and understanding of disease pathways will enable future improvements in interpretation of these complex data sets.

Whilst predictive tools are essential for the prioritisation of variants discovered in next generation sequencing (NGS) studies, ultimately functional validation of the effects of variants on protein function is required to confirm their impact. Given the volume of potentially pathogenic variants being identified in NGS studies, routine functional validation is infeasible. In silico protein modelling approaches may also be used to improve throughput, however these require the prior determination of protein structure, which has not been reported in the majority of genes discussed herein. Overall, it is clear that functional validation is a significant bottleneck in NGS studies and one not readily assuaged.

The limitations of exome sequencing include lack of coverage outside gene coding regions thereby excluding regulatory variants, which may influence risk. Technical limitations include poor coverage of some coding regions thereby missing potential causal variants. Whole genome sequencing offers a solution to these coverage issues, but at higher cost and considerably increased analytical complexity. Given the extent of the missing heritability in CLP, it is likely non-coding regions of the genome play a significant role; whole genome sequencing may therefore provide a valuable tool as sequencing costs continue to drop.

In this study we have limited our analyses to 865 genes with a known/suspected involvement in CLP phenotypes. Whilst this will prevent us from identifying novel aetiological genes, 7 families would be underpowered to identify novel causal genes reliably. Large cohort studies are required in order to identify novel CLP genes; to this end we have made our WES data available in Supplementary File 4 for the use of other researchers.

In conclusion, we have undertaken exome analysis in seven Colombian families with NSCLP phenotypes. We find a deleterious variant in the MSX1 gene in family CL4 which is a strong candidate for causality. Deleterious variants in at least three additional genes may be implicated in NSCLP phenotypes in some of the other families. Although NSCLP is primarily a complex multifactorial phenotype, our study adds to the growing body of evidence that Mendelian sub-forms exist and these are best studied in multi-case families particularly where there are more severe phenotypic features such as bilateral clefting.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Pengelly, R. J. et al. Deleterious coding variants in multi-case families with non-syndromic cleft lip and/or palate phenotypes. Sci. Rep. 6, 30457; doi: 10.1038/srep30457 (2016).

References

Murray, J. Gene/environment causes of cleft lip and/or palate. Clin. Genet. 61, 248–256 (2002).

Collins, A. et al. The potential for next-generation sequencing to characterise the genetic variation underlying non-syndromic cleft lip and palate phenotypes. OA Genet. 1, 10 (2013) http://www.oapublishinglondon.com/abstract/987.

Zucchero, T. M. et al. Interferon regulatory factor 6 (IRF6) gene variants and the risk of isolated cleft lip or palate. N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 769–780 (2004).

Lidral, A. C. et al. Association of MSX1 and TGFB3 with nonsyndromic clefting in humans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 63, 557–568 (1998).

van den Boogaard, M. J., Dorland, M., Beemer, F. A. & van Amstel, H. K. MSX1 mutation is associated with orofacial clefting and tooth agenesis in humans. Nat. Genet. 24, 342–343 (2000).

Leslie, E. J. & Marazita, M. L. Genetics of cleft lip and cleft palate. Am. J. Med. Genet. C. Semin. Med. Genet. 163C, 246–258 (2013).

Lee, S., Wu, M. C. & Lin, X. Optimal tests for rare variant effects in sequencing association studies. Biostatistics 13, 762–775 (2012).

Chandrasekharan, D. & Ramanathan, A. Identification of a novel heterozygous truncation mutation in exon 1 of ARHGAP29 in an Indian subject with nonsyndromic cleft lip with cleft palate. Eur. J. Dent. 8, 528–532 (2014).

Blanton, S. H. et al. Variation in IRF6 contributes to nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 137A, 259–262 (2005).

Pengelly, R. J. et al. A SNP profiling panel for sample tracking in whole-exome sequencing studies. Genome Med. 5, 89 (2013).

Pengelly R. J. et al. Resolving clinical diagnoses for syndromic cleft lip and/or palate phenotypes using whole-exome sequencing. Clin Genet 88, 441–449 (2015).

Stenson, P. D. et al. The Human Gene Mutation Database: building a comprehensive mutation repository for clinical and molecular genetics, diagnostic testing and personalized genomic medicine. Hum. Genet. 133, 1–9 (2014).

Hamosh, A., Scott, A. F., Amberger, J. S., Bocchini, C. A. & McKusick, V. A. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), a knowledgebase of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, D514–D517 (2005).

Liu, X., Jian, X. & Boerwinkle, E. dbNSFP: a lightweight database of human nonsynonymous SNPs and their functional predictions. Hum. Mutat. 32, 894–899 (2011).

Exome Aggregation Consortium et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. bioRxiv 030338 doi: 10.1101/030338 (2015)

Yeo, G. & Burge, C. B. Maximum entropy modeling of short sequence motifs with applications to RNA splicing signals. J. Comput. Biol. 11, 377–394 (2004).

Fuentes Fajardo, K. V. et al. Detecting false-positive signals in exome sequencing. Hum. Mutat. 33, 609–613 (2012).

Sherry, S. T. et al. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 308–311 (2001).

Abecasis, G. R. et al. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature 491, 56–65 (2012).

Fu, W. et al. Analysis of 6,515 exomes reveals the recent origin of most human protein-coding variants. Nature 493, 216–220 (2013).

Thorvaldsdóttir, H., Robinson, J. T. & Mesirov, J. P. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief. Bioinform. 14, 178–192 (2013).

Chiquet, B. T. et al. Variation in WNT genes is associated with non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 2212–2218 (2008).

Menezes, R. et al. Studies with Wnt genes and nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate. Birth Defects Res. A. Clin. Mol. Teratol. 88, 995–1000 (2010).

Mostowska, A. et al. Genotype and haplotype analysis of WNT genes in non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 120, 1–8 (2012).

Lan, Y. et al. Expression of Wnt9b and activation of canonical Wnt signaling during midfacial morphogenesis in mice. Dev. Dyn. 235, 1448–1454 (2006).

Jezewski, P. A. et al. Complete sequencing shows a role for MSX1 in non-syndromic cleft lip and palate. J. Med. Genet. 40, 399–407 (2003).

Satokata, I. & Maas, R. Msx1 deficient mice exhibit cleft palate and abnormalities of craniofacial and tooth development. Nat. Genet. 6, 348–356 (1994).

Romitti, P. A. et al. Candidate genes for nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate and maternal cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption: Evaluation of genotype-environment interactions from a population-based case-control study of orofacial clefts. Teratology 59, 39–50 (1999).

Blanco, R. et al. Evidence of a sex-dependent association between the MSX1 locus and nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in the Chilean population. Hum. Biol. 73, 81–89 (2001).

Beaty, T. H. et al. A Case-Control Study of Nonsyndromic Oral Clefts in Maryland. Ann. Epidemiol. 11, 434–442 (2001).

Jugessur, A. et al. Variants of developmental genes (TGFA, TGFB3 and MSX1) and their associations with orofacial clefts: a case-parent triad analysis. Genet. Epidemiol. 24, 230–239 (2003).

Otero, L., Gutiérrez, S., Cháves, M., Vargas, C. & Bérmudez, L. Association of MSX1 with nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate in a Colombian population. Cleft Palate. Craniofac. J. 44, 653–656 (2007).

Yoshiura, K. et al. Characterization of a novel gene disrupted by a balanced chromosomal translocation t(2;19)(q11.2;q13.3) in a family with cleft lip and palate. Genomics 54, 231–240 (1998).

Wyszynski, D. F. et al. Evidence for an association between markers on chromosome 19q and non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in two groups of multiplex families. Hum. Genet. 99, 22–26 (1997).

Leal, T. et al. Array-CGH detection of a de novo 0.8 Mb deletion in 19q13.32 associated with mental retardation, cardiac malformation, cleft lip and palate, hearing loss and multiple dysmorphic features. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 52, 62–66 (2009).

Kohli, S. S. & Kohli, V. S. A comprehensive review of the genetic basis of cleft lip and palate. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 16, 64–72 (2012).

Ingersoll, R. G. et al. Association between genes on chromosome 4p16 and non-syndromic oral clefts in four populations. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 18, 726–732 (2010).

D’Asdia, M. C. et al. Novel and recurrent EVC and EVC2 mutations in Ellis-van Creveld syndrome and Weyers acrofacial dyostosis. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 56, 80–87 (2013).

Dixon, M. J., Marazita, M. L., Beaty, T. H. & Murray, J. C. Cleft lip and palate: understanding genetic and environmental influences. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 167–178 (2011).

Gajdos, V. et al. Genetics of nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate: is there a Mendelian sub-entity? Ann. génétique 47, 29–39 (2004).

Stanier, P. & Moore, G. E. Genetics of cleft lip and palate: syndromic genes contribute to the incidence of non-syndromic clefts. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13, R73–R81 (2004).

Scapoli, L. et al. Strong evidence of linkage disequilibrium between polymorphisms at the IRF6 locus and nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate, in an Italian population. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 76, 180–183 (2005).

Kerameddin, S., Namipashaki, A., Ebrahimi, S. & Ansari-Pour, N. IRF6 Is a Marker of Severity in Nonsyndromic Cleft Lip/Palate. J. Dent. Res. 94, 226S–232S (2015).

Vieira, A. R. et al. Medical sequencing of candidate genes for nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate. PLoS Genet. 1, e64 (2005).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support for this research from the Newlife Foundation for Disabled Children; the funder had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication. They would also like to gratefully acknowledge Operation Smile, Colombia and the patients who participated in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.J.P. and A.C. performed data analysis and interpretation and wrote the manuscript; L.A., J.M. and I.B. recruited patients and provided clinical detail, R.U.G., E.G.S., J.G. and S.E. contributed to data analysis and interpretation. All authors have seen and contributed to the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Pengelly, R., Arias, L., Martínez, J. et al. Deleterious coding variants in multi-case families with non-syndromic cleft lip and/or palate phenotypes. Sci Rep 6, 30457 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30457

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30457

This article is cited by

-

Identification of novel susceptibility genes for non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate using NGS-based multigene panel testing

Molecular Genetics and Genomics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.