Abstract

Worldwide pollinator declines are attributed to a number of factors, including pesticide exposures. Neonicotinoid insecticides specifically have been detected in surface waters, non-target vegetation, and bee products, but the risks posed by environmental exposures are still not well understood. Pollinator strips were tested for clothianidin contamination in plant tissues, and the risks to honey bees assessed. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) quantified clothianidin in leaf, nectar, honey, and bee bread at organic and seed-treated farms. Total glycogen, lipids, and protein from honey bee workers were quantified. The proportion of plants testing positive for clothianidin were the same between treatments. Leaf tissue and honey had similar concentrations of clothianidin between organic and seed-treated farms. Honey (mean±SE: 6.61 ± 0.88 ppb clothianidin per hive) had seven times greater concentrations than nectar collected by bees (0.94 ± 0.09 ppb). Bee bread collected from organic sites (25.8 ± 3.0 ppb) had significantly less clothianidin than those at seed treated locations (41.6 ± 2.9 ppb). Increasing concentrations of clothianidin in bee bread were correlated with decreased glycogen, lipid, and protein in workers. This study shows that small, isolated areas set aside for conservation do not provide spatial or temporal relief from neonicotinoid exposures in agricultural regions where their use is largely prophylactic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Worldwide pollinator declines have sparked controversy and debates regarding the specific causes of these declines, especially in managed honey bees (Apidae: Apis mellifera)1,2,3. The phenomenon termed colony collapse disorder (CCD) is hypothesized to result from a number of factors including diseases and parasites, in-hive and environmental pesticide exposure, reduced access to quality forage, and changing cultural practices of beekeeping4,5,6. Insecticide exposure, especially to the neonicotinoids, has garnered much attention in recent years, prompting a two-year moratorium by the European Union on their use in flowering crops1, reductions on their use in corn and soy in Ontario, Canada2, and the United States Environmental Protection Agency to enact guidelines limiting pollinator exposures in treated cropland.

However, widespread and prophylactic use of neonicotinoids and other pesticides in the United States7,8 as a result of policy-driven changes in agronomic practices9, particularly in the Upper Midwest, has resulted in decreased access to forage10 (with the removal of vegetation surrounding fields to maximize crop production) and increased risk of neonicotinoid exposure for the majority of the nation’s honey bees during the months of honey production.

Understanding the environmental fate of neonicotinoids improves our perceptions of environmental risks posed by this class of insecticides. Only 2–20% of the active ingredient on treated crop seeds is taken into the developing plant11, and recent data suggests that the remaining majority of the compound is not staying within cropland12,13,14,15,16,17,18. Soil half-lives vary greatly between chemical forms and they may remain for years after initial application (e.g. thiamethoxam: 25–100 days19, clothianidin: 148–1,155 days20). Clothianidin, thiamethoxam, and imidacloprid have been detected in major waterways and wetlands that drain agricultural areas14,16, implicating runoff events in creating long-term exposure scenarios for aquatic organisms. Residues have also been documented in non-target plants adjacent to treated areas12,13,15,18, which serve as critical forage for honey bees and other pollinators. Pesticides are often detected in nectar, honey, pollen, and beeswax17, indicating that contaminated forage provides a potential route of exposure to bees.

With some exceptions, researchers have had difficulty showing field-relevant exposures to neonicotinoids having an appreciable effect on honey bee colony performance4,21, and the levels that have been detected in plants and bee products are arguably not high enough to induce acute mortality in honey bees (thiamethoxam: oral LD50 = 5 ng/bee, clothianidin: oral LD50 = 4 ng/bee22, but see Henry, et al.21]). However, sublethal effects have been observed in bees at field realistic exposures resulting in impaired foraging behavior23,24, decreased reproductive capacity23,25,26,27, and synergistic interactions with other stressors such as pathogens28,29. A typical approach to addressing the effects of pesticides on honey bees has mostly focused on endpoints of colony performance, as honey bees are managed as colonies for honey production and pollination services. High annual losses in the United States30 have been difficult to attribute to neonicotinoids specifically, but sublethal impairment to exposed foragers as measured by nutrient status may be useful in identifying mechanisms by which losses are indirectly sustained, particularly in winter31. Here, we applied measures of glycogen, lipid, and protein levels as proxies for individual bee health, which have been used previously to effectively quantify nutrient status in other insect species (see Pumariño, et al.32 and references therein).

Initially, the aim of this study was to determine whether increasing forage by planting pollinator strips in a corn and soy dominated region would serve to buffer against harmful effects of plant-incorporated pesticides, specifically the neonicotinoids, with organic corn fields serving as controls. However, when it became apparent that an unintended consequence of planting pollinator strips adjacent to treated cropland meant that they became a source for neonicotinoid exposure, the goal shifted to determine whether pollinator strips were themselves harmful to the bees. The objectives of the present study were to 1) evaluate the presence of clothianidin in pollinator strips near treated cropland, 2) quantify the amounts of clothianidin in floral tissues, and 3) determine whether accumulated levels pose a significant risk to honey bees.

Results

Clothianidin concentrations in plant tissues

Plant species accumulated different levels of clothianidin in their leaf tissues (F = 26.8, d.f. = 6,61, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Sunflowers (Helianthus annuus), which started blooming in July, accumulated the highest concentrations in their leaves, ranging from 0–81 ppb clothianidin. Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) and phacelia (Phacelia tanacetifolia), which start blooming within a month of germination in the spring, had significantly lower concentrations recovered in leaf tissue, ranging from 0–52 ppb and 0–33 ppb, respectively (Fig. 1).

Nectar was only collected in sufficient quantities for analysis from mustard (Sinapis alba), buckwheat, phacelia, sunflower, and crimson clover (Trifolium incarnatum). However, due to low replication, sunflower and crimson clover were excluded from analysis. Clothianidin was detected in nectar collected by honey bees (Fig. 2), with significant differences between plant species (F = 27.4, d.f. = 2,26, P < 0.001).

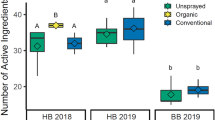

Seed-treated versus organic cornfields

Pollinator strips planted adjacent to seed-treated cornfields and untreated organic cornfields had similar clothianidin concentrations in leaf tissues (F = 0.01, d.f. = 1,61, P = 0.92), and nectar (F = 0.01, d.f. = 1,26, P = 0.91). The proportion of contaminated plants on seed treated and organic farms were not statistically different for any of the plant species tested (Table 1). Clothianidin levels in honey were also similar between seed-treated and organic farms (F = 0.26, d.f. = 1,12, P = 0.62), with no differences in residue concentrations between sampling dates (onset of bloom versus post-flowering at the end of the summer; F = 0.40, d.f. = 1,12, P = 0.54). Honey levels averaged (±SEM) 6.61 ± 0.88 ppb per hive, approximately seven times greater than concentrations recovered in nectar (0.94 ± 0.09 ppb, averaged across all species). In contrast, bee bread (pollen returned to the hive and stored for food) recovered from the hives located on organic farms had significantly lower levels of clothianidin than bee bread from hives near seed-treated fields (F = 5.40, d.f. = 1,12, P = 0.04), with bee bread from seed-treated farms containing nearly twice as much clothianidin (organic: 25.8 ± 3.0 ppb; seed-treated: 41.6 ± 2.9 ppb). Pesticide residues in bee bread were also unaffected by sampling date (F = 0.48, d.f. = 1,12, P = 0.50) and there was no significant interaction between sampling date and treatment (F = 1.18, d.f. = 1,12, P = 0.30).

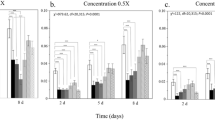

Honey bee health

Increasing concentrations of clothianidin in the bee bread collected by honey bees were associated with significant declines in glycogen (F = 6.85, d.f. = 1,6, P = 0.04) and lipids (F = 8.73, d.f. = 1,6, P = 0.03) in the worker bees at those respective sites, with a negative association in total proteins (F = 4.84, d.f. = 1,6, P = 0.07) (Fig. 3). Bees from the hives at organic and treated farms had a similar nutritional status (glycogen: F = 0.82, d.f. = 1,5, P = 0.41; lipids: F = 1.32, d.f. = 1,5, P = 0.30; protein: F = 0.21, d.f. = 1,5, P = 0.67). Clothianidin concentrations of in-hive honey had no effect on honey bee nutritional status (glycogen: F = 0.43, d.f. = 1,6, P = 0.54; lipids: F = 2.68, d.f. = 1,6, P = 0.15), although a negative trend was observed between honey contamination levels and bee protein quantities (F = 5.08, d.f. = 1,6, P = 0.07).

Discussion

This study indicates that neonicotinoid contamination unintentionally negates, in part, the organic status of small, isolated farms, and questions the benefits of deploying habitat for conservation purposes in the absence of integrated pest management (IPM) practices on cropland. A large proportion of cropland in the region receives neonicotinoid seed treatments7,33, despite empirical data questioning the benefits of these treatments for producers of a number of commodities34,35,36. An estimated 42 million ha of maize, soybean, and cotton cropland are seed-treated with neonicotinoids in the United States7. Regulations dictate that buffer strips between organic and conventional farms be sufficient to prevent unintended application of prohibited substances37 and are typically 7.5–9 m wide, though most contaminated planter dust falls within 5 m of the treated field38,39,40. But given the hydrophilic nature of the neonicotinoids (e.g. log KOW clothianidin = 0.7), we hypothesize that spatially isolated organic farms are contaminated by neonicotinoids from sources other than planter dust, and that water14,16 and soil pathways merit additional study to explain contamination at sites spatially and temporally isolated from treated areas. In short, an unintended consequence of prophylactic use of neonicotinoid seed treatments may be to reduce the benefits of pollinator conservation plans.

In addition to spatially limited forage refugia, we found no temporal relief from non-target contaminated forbs as evidenced by high residue levels recovered in late summer blooming sunflowers (Fig. 1), further suggesting that contamination was not solely from a temporally distinct early season source like planter dust. Thus, it does not appear that plants blooming closer to corn planting necessarily accumulate higher concentrations of clothianidin. Peredovik sunflowers are an ornamental variety, but wild sunflowers are native throughout the upper Great Plains region. This species accumulating the highest concentrations in leaf tissues is contrary to what would be expected given the size of this species relative to the others tested41, assuming soil residues were uniform across a particular site. Concentrations were 135 times higher than those reported for a crop sunflower variety treated with thiamethoxam in the R5 stage36. However, Bonmatin et al.12 reported a sharp increase in imidacloprid levels in leaves during flowering for five different cultivated varieties. These differences within a single species may be due to physiological differences between cultivars or the result of abiotic and soil conditions affecting uptake8. Regardless, the risk of exposure associated with honey bees foraging on wildflowers is consistently present in space, time, and across flowering forage species within this highly developed agricultural region.

Honey bees are known to have high forage fidelity, and when foraging will only collect resources from a particular plant species42, in contrast to other native bee species. It is therefore highly probable that nectar recovered in the crops of honey bees came from the plant species they were collected from. This proved to be an effective and time-saving means for collecting nectar for clothianidin analysis. Residues in buckwheat and phacelia nectar were 72 and 86% less than those recovered in their leaf tissues, respectively, with mustard nectar containing 1.8 times greater concentrations than the leaf tissue. As was the case with leaf tissues, differences were significant among species, indicating physiological mediation by plants with regard to how much clothianidin is taken up from soils. Across plant species, the average concentration detected in nectar was lower here than concentrations recovered from the nectar of neonicotinoid-treated flowering crops (e.g. clover: 2882–2992 ng/g (from a spray application as opposed to a seed treatment)43; curcubits: 17.6 ng/g44, 10–11 ppb45; oilseed rape: 4.2 ng/g46, ≤2.24 ppb47; ornamental flowers: 21–45 ppm48), but similar to those levels reported for wildflowers growing near treated fields (0.10 ng/g13, 0–6.5 ng/ml15,27). The amount of clothianidin in honey from our study was approximately seven times more concentrated than nectar, which would be expected given the average water content of nectar versus honey. However, this also indicates that clothianidin is not breaking down during the process of nectar conversion to honey, a point made by Dively et al.49 for imidacloprid.

The concentrations we recovered in bee bread were greater at both organic and seed treated farms than those reported elsewhere for contaminated pollen12,13,17,27,45,47. This may be the result of compounding levels of clothianidin from continuous plantings of treated crops year after year in a region dominated by treated corn and soybeans, and minimal levels of breakdown in soils. Further analyses would be needed to quantify clothianidin residues in eastern South Dakota to test this hypothesis.

Using the concentrations we recovered in honey and bee bread, a honey bee worker would need to consume approximately 610 mg of honey or 95 mg of bee bread at one time in order to experience lethality at the LD50 level. This exceeds the amount of honey and pollen consumed daily by adult workers (honey: 13–18 mg/day, pollen: 6.5 mg/day) and larvae (honey: 15–29 mg/day, pollen: 1.1 mg/day)22, if we assume the same LD50 for both. These LD50s are largely lacking for bee larvae, and are also strongly affected by the physiological status of the bees tested, so may not be an accurate perception of field-collected bees in our study. Assuming that these LD50s are an accurate estimate, acute mortality at the levels observed in our study is unlikely. Nevertheless, clothianidin concentrations in bee bread were associated with declines in nutritional status of the bees under field conditions. While neonicotinoids have been shown to reduce the viability of honey bee queens25,26, it has been more difficult to detect significant effects on workers and overall colony performance, possibly owing to “superorganism resilience”50 or differential detoxification51, versus declines found for other eusocial bees and solitary native bees27. However, using lethality as an endpoint fails to take into account stress that may be experienced by an individual as a result of exposure, which could weaken an individual enough that additional sublethal stressors, such as disease or other pesticides, lead to mortality or deleterious behavioral modification.

Glycogen and lipids are synthesized and stored in the fat body of insects, and are important as immediate energy sources and to be used during flight and diapause, respectively52. Lipids are particularly important in the success of overwintering species31. Since CCD was first recognized in 2006, beekeepers have reported 30% annual losses of colonies30, many of which occur during the winter months. Significant decreases in individual honey bee lipid storage late in the summer as a result of clothianidin exposure could therefore have significant implications for overwintering success of winter bees and entire colonies. Fat content has also been strongly correlated with reproductive capacity in females of other species32,53. Should declines in worker lipid content reflect similar declines in queens, this could have negative consequences for egg-laying. Our study documented declines in lipids and glycogen, which also have importance in immunity52, and could explain why sublethal neonicotinoid exposures coincide with increases in disease infection rates28,29.

Conclusions

The paradox of the present study is that pollinator strips intended to enhance honey bee health in a heavily developed agricultural landscape resulted in declining bee health due to unintended accumulation of clothianidin from adjacent treated corn fields at both organic and conventional farms. Although pollinator strips on organic farms were generally more than 140 m from the nearest treated crop (Supplementary Table S1), this was not far enough to fully isolate these strips from negative seed treatment effects. It has been suggested that any harmful exposures resulting from non-target plant uptake of neonicotinoids would be diluted by the fact that honey bees visit numerous flowers on a single foraging expedition54. Dilution would be difficult in highly developed agricultural areas like eastern South Dakota where neonicotinoid seed treatments are ubiquitous. We found that clothianidin uptake was the same at treated and untreated locations, and was present in plant tissues throughout the growing season. The concentrations of clothianidin recovered in bee bread were high enough to impair glycogen and lipid accumulation, with significant implications for overwintering success and reproductive potential of queens. While pollinator strips and uncropped areas have the potential to serve as buffers to pesticide exposures for bees55, our results indicate that their placement within the landscape needs to be carefully considered. In all likelihood, reducing bee exposures to these pesticides will require reductions in their use across the landscape and a movement away from prophylactic applications towards more integrated pest management strategies, as has been suggested elsewhere2.

Materials and Methods

Site selection and preparation

Pollinator strips were planted adjacent to 16 corn fields during the 2014 and 2015 growing seasons (n = 8 sites in each year) (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S1). Half of these were located on certified organic farms (fields in organic cropping practices for at least 5 years) planted with organic field corn (non-Bt and no insecticidal seed treatments), and the other half on conventional farms planted with Bt-transgenic field corn seed-treated with thiamethoxam (as Cruiser) or clothianidin (as Poncho or Acceleron), with 0.25 mg active ingredient/seed (Supplementary Table S1). Within a particular year, sites were located greater than 5 km apart, such that honey bees could not forage between pollinator strips. All corn fields were maintained according to standard agronomic practices (herbicide, fungicide, tillage, and fertilizer regimens) as decided by the producers. Organic fields in the region are typically characterized by higher rates of tillage than conventional fields for weed control and an absence of genetically modified crops or synthetic pesticides or fertilizers. The study region is dominated by corn and soybean row crops and degraded pasture lands, together accounting for 75% of regional land use10.

Native and naturalized annual and perennial forb species were included in the pollinator strip mix (Millborn Seeds, Brookings, SD), which was then optimized in 2015 based on 2014 observational data of pollinator visitation and floral preference (Table 2). In addition to including a diversity of colors and floral structure types, this mix contained early and late season flowering forbs to provide honey bee forage for the entire growing season. Pollinator strips were seeded at a rate of 22 kg/ha using a planter to plant 6 m by 305 m strips (approximately 0.2 ha) directly adjacent to the corn fields. These were planted by late May as soon as field conditions were suitable following corn planting. At each pollinator strip, four honey bee hives were maintained for the duration of the experiment according to local beekeeping practices. Pollinated crops such as flax, canola, and sunflower are uncommon in the study region, and to our knowledge there were no fields located within 3 km of our study locations. Throughout the growing season, honey bees were observed to actively forage in the pollinator strips adjacent to their hives. Thus, the majority of resources brought back to the hives were likely from the pollinator strips as opposed to other mass-flowering crops.

Sample collection

The most abundant flowering plant species that bloomed across most or all of the study region were selected for clothianidin analysis. In 2014, this included buckwheat, mustard, partridge pea, phacelia, safflower, and sunflower. In 2015, these species were buckwheat, crimson clover, mustard, partridge pea, phacelia, plains coreopsis, safflower, and sunflower. Although mustard was excluded from the seed mix in 2015, wild mustard grew as a weed at organic sites, and was included for analysis in both years.

Leaf tissue (4.5 mm leaf discs) was collected from five different plants at each site when the plant was flowering. Honey and bee bread samples (n = 5 cells each) were collected twice in 2015 from each site when the pollinator strips started to bloom, and again when the pollinator strips were finished flowering in the first week of September (n = 10 samples total per site). Nectar was obtained from foraging honey bees after they were observed landing on a particular flower species. All honey bees on a particular species were tapped into a cup containing 70% ethanol, and the crop removed for clothianidin analysis. Due to the high forage fidelity of honey bee workers42, we can assume that all nectar recovered in the crop came from the same species on which the bee landed. All samples were frozen at −20 °C until analysis.

Clothianidin analysis

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were used to detect clothianidin in plant samples (product no. 500800, Abraxis, Warminster, PA). Thiamethoxam metabolizes to clothianidin in plants56, thus a test for total clothianidin would therefore capture uptake of both seed treatment chemistries. This technique provides an affordable and highly sensitive means of rapidly quantifying concentrations in environmental samples. The test also detects imidacloprid, a chemistry absent from the study sites, with negligible cross-reactivity with other neonicotinoid compounds. ELISAs were conducted according to manufacturer instructions.

Individual leaf discs were homogenized in 258 μl of ddiH20 with a sterile plastic pestle, placed on a shaker for 1 h, and centrifuged at 16,100 g for 3 min. The supernatant was diluted to 20% prior to analysis. In order to control for any plant matrix effects, the species being analyzed were also grown in the greenhouse free from neonicotinoid exposure. Leaf extract from these control plants was spiked with clothianidin (product no. 33589, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to create a 20% leaf extract with known concentrations for the standard curves18,36.

Pollen from the bee bread samples (0.05 g) was germinated in 2 ml of a 10% sucrose/0.1% boric acid solution for 2 h at 23 °C57. This solution was centrifuged, and the supernatant used in analysis without further dilution. Quality control checks using clothianidin-spiked corn pollen from untreated plants grown in the greenhouse revealed no interference of the pollen matrix with the ELISA. As a result, water was used as the standard curve matrix.

Honey samples (0.2 g) were individually diluted in 1 ml of water. Matrix interference from waxes, pigments, and carbohydrates has been previously documented to occur in ELISAs analyzing honey58, so in our assays the honey solutions were diluted 20-fold prior to analysis. Water was used as the matrix in the standard curves.

Nectar was extracted from the crops of honey bees collected foraging in the conservation strips. The crops of multiple bees were combined until the 50 μl of nectar necessary for analysis was obtained. These samples were homogenized using a sterile plastic pestle and centrifuged (16,100 g for 3 min) to remove membranes and any particulates present in the crop. Nectar was used in ELISA analysis without further dilution with water in the standards.

In order to determine whether a sample was positive, that sample’s absorbance was compared to the average absorbance of the controls on the same plate, multiplied by twice the standard deviation of those controls18. If the absorbance was less than this value, the sample was considered positive, and compared to the absorbance of standard concentrations of 0, 0.03125, 0.0625, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2 μg clothianidin/L (ppb). All standard curves were run in triplicate on each plate. For all samples, absorbance was recorded at 450 nm using a μ Quant (Biotek Instruments, Winooski, VT) microplate reader.

Nutrient analyses

Honey bee adults were collected from the base of the hives at each location every two weeks for 10 weeks and stored in 70% EtOH at −20 °C until analysis. The legs and gut were removed, and the remaining carcass (n = 10 per site per sampling date) homogenized in 100 μl of 1% PBS with a sterile plastic pestle. A 15 μl aliquot for each specimen was then added to 300 μl of methanol-chloroform (2:1 solution) and centrifuged at 16,100 g for 4 min (following Pumariño, et al.32). The supernatant was transferred to a glass tube for the phosphovanillin lipid assay (modified from Vanhandel59), and the pellet retained for the anthrone glycogen assay (modified from Vanhandel60). A separate 10 μl aliquot was diluted to 10% with ddiH2O for analysis with the Bradford protein assay61 (Bio-Rad protein assay kit II, product no. 500-0002) following the manufacturer’s instructions for microplate assays.

Lipid, glycogen, and protein content per honey bee were calculated from the absorbance values (measured at 525 nm [lipids], 630 nm [glycogen], and 595 nm [protein]) using a standard curve. Standard materials were extra virgin olive oil (54 μl olive oil in 50 ml chloroform), glycogen from oyster (25 mg oyster type II [Sigma-Aldrich] in 25 ml water), and protein assay standard II (bovine serum albumin) for lipids, glycogen, and protein, respectively. Standard concentrations were 0, 1, 5, 10, 25, 50, 75, and 100 μg for lipids and glycogen and 0, 25, 50, 100, 250, and 500 μg for protein. All samples and standards were analyzed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using JMP Pro v.12.1.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Because data upheld assumptions of normality and homogeneous variances, no transformations were necessary. Leaf data were analyzed using a linear mixed model approach to control for sample independence, with the model testing for differences in clothianidin accumulation between plant species, treatment (organic versus seed-treated locations), and an interaction between these factors, with the unit of replication being plant species per site-year. The random effect was the site-year. Similarly, clothianidin accumulation in bee bread and honey were analyzed using a linear mixed model, with site being the unit of replication and factors being sample date, treatment, and an interaction. Linear mixed model analysis was also used to analyze the nectar data. Because samples from individual bees were pooled in order to obtain an adequate volume for analysis, there was unequal replication between sites, thus the unit of replication became the individual sample and an analysis of organic vs. seed treated treatments was not possible. In order to determine whether there was a difference between the likelihood of encountering contaminated forage at conventional and organic sites, a z-test of clothianidin-positive leaf samples was used. Total glycogen, lipids, and protein were averaged for each site-year and regressed against the clothianidin concentrations in bee bread and honey to quantify any effects of forage exposures to overall health.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Mogren, C. L. and Lundgren, J. G. Neonicotinoid-contaminated pollinator strips adjacent to cropland reduce honey bee nutritional status. Sci. Rep. 6, 29608; doi: 10.1038/srep29608 (2016).

References

European Commission. No 485/2013 of 24 May 2013 amending Implementing Regulation (EU) No 540/2011, as regards the conditions of approval of the active substances of clothianidin, thiamethoxam and imidacloprid, and prohibiting the use and sale of seeds treated with plant protection products containing those active substances. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) (2013).

Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change. Neonicotinoid regulations. Available at http://www.ontario.ca/environment-and-energy/neonicotinoid-regulations Date of access:12/04/2016 (2015).

U.S. E.P.A. Pollinator protection labeling for nitroguanidine neonicotinoid products. Available at http://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2013-11/documents/bee-label-info-ltr.pdf Date of access:12/04/2016 (2013).

Lundin, O., Rundlof, M., Smith, H. G., Fries, I. & Bommarco, R. Neonicotinoid insecticides and their impacts on bees: A systematic review of research approaches and identification of knowledge gaps. PLoS One 10, 0136928 (2015).

Potts, S. G. et al. Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol Evol 25, 345–353 (2010).

Vanbergen, A. J. et al. Threats to an ecosystem service: pressures on pollinators. Front Ecol Environ 11, 251–259 (2013).

Douglas, M. R. & Tooker, J. F. Large-scale deployment of seed treatments has driven rapid increase in use of neonicotinoid insecticides and preemptive pest management in US field crops. Environ Sci Technol 49, 5088–5097 (2015).

Goulson, D. An overview of the environmental risks posed by neonicotinoid insecticides. J Appl Ecol 50, 977–987 (2013).

Fausti, S. W. The causes and unintended consequences of a paradigm shift in corn production practices. Environ Sci Policy 52, 41–50 (2015).

Mogren, C. L., Rand, T. A., Fausti, S. W. & Lundgren, J. G. The effects of crop intensification on the diversity of native pollinator communities. Environ Entomol doi: 10.1093/ee/nvw1066 (2016).

Sur, R. & Stork, A. Uptake, translocation and metabolism of imidacloprid in plants. B Insectol 56, 35–40 (2003).

Bonmatin, J. et al. In Environmental Chemistry Ch. 44, 483–494 (Springer, 2005).

Botias, C. et al. Neonicotinoid residues in wildflowers, a potential route of chronic exposure for bees. Environ Sci Technol 49, 12731–12740 (2015).

Hladik, M. L., Kolpin, D. W. & Kuivila, K. M. Widespread occurrence of neonicotinoid insecticides in streams in a high corn and soybean producing region, USA. Environ Pollut 193, 189–196 (2014).

Krupke, C. H., Hunt, G. J., Eitzer, B. D., Andino, G. & Given, K. Multiple routes of pesticide exposure for honey bees living near agricultural fields. PLoS One 7, e29268 (2012).

Main, A. R. et al. Snowmelt transport of neonicotinoid insecticides to Canadian Prairie wetlands. Agric Ecosyst Environ 215, 76–84 (2016).

Mullin, C. A. et al. High levels of miticides and agrochemicals in North American apiaries: Implications for honey bee health. PLoS One 5, e9754 (2010).

Pecenka, J. R. & Lundgren, J. G. Non-target effects of clothianidin on monarch butterflies. Naturwissenschaften 102 (2015).

Syngenta Group. Envirofacts. Syngenta crop protection fact sheet: Thiamethoxam. Available from http://www.syngentacropprotection.com/env_stewardship/futuretopics/thiomethoxamenvirofacts_7-19-05.pdf Date of access:12/04/2016 (2005).

U. S. E. P. A. Pesticide fact sheet: Clothianidin. Available at https://www3.epa.gov/pesticides/chem_search/reg_actions/registration/fs_PC-044309_30-May-03.pdf Date of access:12/04/2016 (2003).

Henry, M. et al. Reconciling laboratory and field assessments of neonicotinoid toxicity to honeybees. P R Soc B 282, 20152110 (2015).

Sanchez-Bayo, F. & Goka, K. Pesticide residues and bees–a risk assessment. PLoS One 9, e94482 (2014).

Gill, R. J., Ramos-Rodriguez, O. & Raine, N. E. Combined pesticide exposure severely affects indivdual- and colony-level traits in bees. Nature 491, 105–108 (2012).

Fischer, J. et al. Neonicotinoids interfere with specific components of navigation in honeybees. PLoS One 9, e91364 (2014).

Pettis, J. S., Rice, N. & Joselow, K., vanEngelsdorp, D. & Chaimanee, V. Colony failure linked to low sperm viability in honey bee (Apis mellifera) queens and an exploration of potential causative factors. PLoS One 11, e0147220 (2016).

Williams, G. R. et al. Neonicotinoid pesticides severely affect honey bee queens. Sci Rep 5, 14621 (2015).

Rundlof, M. et al. Seed coating with a neonicotinoid insecticide negatively affects wild bees. Nature 521, 77–U162 (2015).

Alburaki, M. et al. Neonicotinoid-coated Zea mays seeds indirectly affect honeybee performance and pathogen susceptibility in field trials. PLoS One 10, e0125790 (2015).

Pettis, J. S. et al. Crop pollination exposes honey bees to pesticides which alters their susceptibility to the gut pathogen Nosema ceranae . PLoS One 8, e70182 (2013).

VanEngelsdorp, D. et al. A national survey of managed honey bee 2010-11 winter colony losses in the USA: results from the Bee Informed Partnership. J Apic Res 51, 115–124 (2012).

Hahn, D. A. & Denlinger, D. L. Meeting the energetic demands of insect diapause: Nutrient storage and utilization. J Insect Physiol 53, 760–773 (2007).

Pumariño, L., Alomar, O. & Lundgren, J. G. Effects of floral and extrafloral resource diversity on the fitness of an omnivorous bug, Orius insidiosus. Entomol Exp Appl 145, 181–190 (2012).

Hunt, G. & Krupke, C. Managed pollinator CAP (Coordinated Agricultural Project): A national research and extension initiative to reverse pollinator decline: Neonicotinoid seed treatments and honey bee health. Am Bee J 152, 889–891 (2012).

Myers, C. & Hill, E. Benefits of neonicotinoid seed treatments to soybean production. United States Environmental Protection Agency (2014).

Stevens, S. & Jenkins, P. Heavy costs: Weighing the value of neonicotinoid insecticides in agriculture. Center for Food Safety. Available from http://www.centerforfoodsafety.org/files/neonic-efficacy_digital_29226.pdf Date of access:12/04/2016 (2014).

Bredeson, M. M. & Lundgren, J. G. Thiamethoxam seed treatments have no impact on pest numbers or yield in cultivated sunflowers. J Econ Entomol 108, 2665–2671 (2015).

National Organic Program. 7 C.F.R. § 205. Available from http://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=f74e37f28adf53fd072422e7492cf956&mc=true&node=pt7.3.205&rgn=div5 Date of access:12/04/2016 (2015).

Devarrewaere, W. et al. Quantitative 3D shape description of dust particles from treated seeds by means of X-ray micro-CT. Environ Sci Technol 49, 7310–7318 (2015).

Tapparo, A. et al. Assessment of the environmental exposure of honeybees to particulate matter containing neonicotinoid insecticides coming from corn coated seeds. Environ Sci Technol 46, 2592–2599 (2012).

Xue, Y. et al. Quantifying neonicotinoid insecticide residues escaping during maize planting with vacuum planters. Environ Sci Technol 49, 13003–13011 (2015).

Balfour, N. J., Carreck, N. L., Blanchard, H. E. & Ratnieks, F. L. W. Size matters: Significant negative relationship between mature plant mass and residual neonicotinoid levels in seed-treated oilseed rape and maize crops. Agric Ecosyst Environ 215, 85–88 (2016).

Free, J. The flower constancy of honeybees. J Anim Ecol 32, 119–131 (1963).

Larson, J. L., Redmond, C. T. & Potter, D. A. Mowing mitigates bioactivity of neonicotinoid insecticides in nectar of flowering lawn weeds and turfgrass guttation. Environ Toxicol Chem 34, 127–132 (2015).

Dively, G. P. & Kamel, A. Insecticide residues in pollen and nectar of a cucurbit crop and their potential exposure to pollinators. J Agr Food Chem 60, 4449–4456 (2012).

Stoner, K. A. & Eitzer, B. D. Movement of soil-applied imidacloprid and thiamethoxam into nectar and pollen of squash (Cucurbita pepo). PLoS One 7, e39114 (2012).

Pohorecka, K. et al. Residues of neonicotinoid insecticides in bee collected plant materials from oilseed rape crops and their effect on bee colonies. J Apic Res 56, 115–134 (2012).

Cutler, G. C. & Scott-Dupree, C. D. Exposure to clothianidin seed-treated canola has no long-term impact on honey bees. 100, 765–772 (2007).

Krischik, V., Rogers, M., Gupta, G. & Varshney, A. Soil-applied imidacloprid translocates to ornamental flowers and reduces survival of adult Coleomegilla maculata, Harmonia axyridis, and Hippodamia convergens lady beetles, and larval Danaus plexippus and Vanessa cardui butterflies. PLoS One 10, e0119133 (2015).

Dively, G. P., Embrey, M. S., Kamel, A., Hawthorne, D. J. & Pettis, J. S. Assessment of chronic sublethal effects of imidacloprid on honey bee colony health. PLoS One 10, e0118748 (2015).

Straub, L., Williams, G. R., Pettis, J. S., Fries, I. & Neumann, P. Superorganism resilience: eusociality and susceptibility of ecosystem service providing insects to stressors. Insect Sci 12, 1–4 (2016).

Cresswell, J. E., Robert, F. X., Florance, H. & Smirnoff, N. Clearance of ingested neonicotinoid pesticide (imidacloprid) in honey bees (Apis mellifera) and bumblebees (Bombus terrestris). Pest Manag Sci 70, 332–337 (2014).

Arrese, E. L. & Soulages, J. L. Insect fat body: Energy, metabolism, and regulation. Annu Rev Entomol 55, 207–225 (2010).

Toth, A. L., Bilof, K. B. J., Henshaw, M. T., Hunt, J. H. & Robinson, G. E. Lipid stores, ovary development, and brain gene expression in Polistes metricus females. Insect Soc 56, 77–84 (2009).

Godfray, H. C. J. et al. A restatement of the natural science evidence base concerning neonicotinoid insecticides and insect pollinators. P Roy Soc Lond B Bio 281, 20140558 (2014).

Park, M. G., Blitzer, E. J., Gibbs, J., Losey, J. E. & Danforth, B. N. Negative effects of pesticides on wild bee communities can be buffered by landscape context. P R Soc B 282, 20150299 (2015).

Nauen, R., Ebbinghaus-Kintscher, U., Salgado, V. L. & Kaussmann, M. Thiamethoxam is a neonicotinoid precursor converted to clothianidin in insects and plants. Pestic Biochem Phys 76, 55–69 (2003).

Pilorget, L., Buckner, J. & Lundgren, J. G. Sterol limitation in a pollen-fed omnivorous lady beetle (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). J Insect Physiol 56, 81–87 (2010).

Ma, H. et al. Application of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for quantification of the insecticides imidacloprid and thiamethoxam in honey samples. Food Addit Contam 26, 713–718 (2009).

Vanhandel, E. Rapid determination of total lipids in mosquitos. J Am Mosq Control Assoc 1, 302–304 (1985).

Vanhandel, E. Rapid determination of glycogen and sugars in mosquitos. J Am Mosq Control Assoc 1, 299–301 (1985).

Bradford, M. M. Rapid and sensitive method for quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing priciple of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72, 248–254 (1976).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Claire Bestul, Michael Bredeson, Janet Fergen, Dakotah Grosz, Kae Januschka, Nathan Koens, Marti LaValle, Abigail Martens, Jacob Pecenka, Greta Schen, Casey Snyder, and Cally Strobel for their assistance with data collection. We would also like to thank Adee Honey Farms (Bruce, SD) and the farmers for providing access to bee hives and land for the duration of this study. This research was funded by two years of support from the National Honey Board and USDA-ELI grant 2016-67012-24826. Mention of any proprietary products does not constitute endorsement by the USDA-ARS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.L.M. designed the experiments, performed field work and collected samples, and performed all chemical analyses in the lab. C.L.M. and J.G.L. performed data analysis, discussed the results, and contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Mogren, C., Lundgren, J. Neonicotinoid-contaminated pollinator strips adjacent to cropland reduce honey bee nutritional status. Sci Rep 6, 29608 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29608

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29608

This article is cited by

-

Neonicotinoid contamination in wildflowers collected from citrus orchards in a northwestern Mediterranean Region (Spain) after tree foliar treatments

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2022)

-

Measuring foraging preferences in bumble bees: a comparison of popular laboratory methods and a test for sucrose preferences following neonicotinoid exposure

Oecologia (2021)

-

An update of the Worldwide Integrated Assessment (WIA) on systemic insecticides. Part 1: new molecules, metabolism, fate, and transport

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2021)

-

An update of the Worldwide Integrated Assessment (WIA) on systemic insecticides. Part 2: impacts on organisms and ecosystems

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2021)

-

Chronic within-hive video recordings detect altered nursing behaviour and retarded larval development of neonicotinoid treated honey bees

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.