Abstract

Some vertebral fractures come to clinical attention but most do not. This cross-sectional survey aimed to clarify the associations of self-reported height loss and kyphosis with vertebral fractures. We enrolled 407 women aged 60–92 years who visited our orthopaedic clinic between June and August 2014 in our study. Inclusion criteria were lateral radiography followed by completion of a structured questionnaire in this study. The primary outcome was vertebral fracture diagnosed on lateral radiography and graded using a semiquantitative grading method, from SQ0 (normal) to SQ3 (severe). Self-reported kyphosis was defined as none, mild to moderate, severe. Self-reported height loss was defined as <4 cm or ≥4 cm. Number of SQ1 fracture was associated only with kyphosis. Self-reported severe kyphosis was significantly associated with increased numbers of ≥SQ2 vertebral fractures (p = 0.007). Height loss ≥4 cm was significantly associated with increased ≥SQ2 grade fractures (p < 0.001). Odds ratios (ORs) for fractures associated with mild-to-moderate and severe kyphosis were 2.1 [95% confidence interval 1.4 to 3.3) and 4.2 (1.8 to 9.5), respectively. OR for fractures associated with height loss ≥4 cm was 2.3 (1.4 to 3.7). Self-reported kyphosis may be useful for identifying Japanese women aged ≥60 years who have undetected vertebral fractures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoporosis (OP) is one of the most common metabolic bone disorders worldwide. It has been defined as a skeletal disorder characterized by compromised bone strength, predisposing a person to increased risk of fracture. Bone strength primarily reflects the integration of bone density and bone quality1. Bone fragility fracture is considered a complication of OP2. Prevention of bone fragility fractures is the primary therapeutic goal when individuals have OP. Although bone mineral density (BMD) measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is usually used for diagnosing OP, the Japanese 2015 OP guideline states that when a fragility fracture (e.g., a proximal femoral fracture or vertebral fracture) is present, the patient is diagnosed as having OP regardless of their BMD values3.

Vertebral fracture is the most frequent of these fragility fractures in Japan. The vertebral fracture rate is higher in Asians than in Caucasians4. In addition, among Asians, the prevalence of vertebral fracture was highest in the Japanese5. Because the presence and number of vertebral fractures are associated with mortality6, Japanese elderly populations who have vertebral fractures should be referred to medical professionals and diagnosed as quickly as possible.

Ross reviews that some patients with vertebral fractures experience intolerable pain, whereas about half of all patients with radiographically identified vertebral fractures had no symptoms7. Additionally, Vogt et al. describe that approximately two thirds of women with radiographic evidence of vertebral fracture are unaware of the fracture8. These suggest that despite the high prevalence of vertebral fracture, many vertebral fractures remain undiagnosed. Vogt et al. finally developed 5 self-reported simple items to identify women 55 years and older who were likely to have undiagnosed vertebral fractures. Kendler et al. recently reviewed that the recognition of vertebral fractures in imaging reports obtained for purposes other than the investigation for vertebral fracture in a hospital setting is generally poor9. They also summarize that risk of future vertebral fracture increases with increasing number and severity of prevalent symptomatic and asymptomatic (morphometric) vertebral fractures. Although both asymptomatic (morphometric) and symptomatic vertebral fracture can be diagnosed using the Genant semiquantitative method10, we should carefully assess vertebral fractures on lateral radiographs in patients who have symptoms like back pain if simple items imply the possibility of having a fracture. Further, if simple items imply the possibility of having a vertebral fracture, we should take lateral radiographs even in asymptomatic patients, especially when considering a large number of patients.

Kyphosis and height loss, which is determined by comparing height at the time of measurement with that at a younger age, are considered useful surrogate markers or screening tools for vertebral fractures in older people11,12. Several thresholds for height loss have been suggested to identify individuals who have asymptomatic vertebral fractures13,14,15,16. Because the spine is frequently involved, elderly women with kyphosis due to multiple compression fractures are common17. After adjustment for age, a 15° increase in kyphosis was associated with the presence of a vertebral fracture [odds ratio (OR) 1.57]18. However, there is no available methodology to diagnose kyphosis simply. Since it is likely that patients with undiagnosed vertebral fractures may feel kyphosis themselves, it is very important for us to demonstrate whether simple self-reported kyphosis is associated with the presence of vertebral fractures determined by lateral radiographs.

We hypothesized that simple self-reported kyphosis may be associated with the presence of vertebral fractures in Japanese women aged ≥60 years. The aim of this study, therefore, was to clarify the associations among self-reported kyphosis, self-reported height loss calculated according to the difference in current height and self-reported height at a younger age, and the presence and number of vertebral fractures that were detected on lateral radiographs in older Japanese women.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and determination of vertebral fractures

Among patients aged ≥60 years who visited our orthopaedic clinic during June through August 2014, the women were invited to complete a structured questionnaire. Women who refused to provide written informed consent or who did not undergo lateral spine radiography ahead of completing a structured questionnaire examination were excluded from the study. Women who had many missing data in their questionnaire were also excluded from the study. Lateral radiographs of the spine were evaluated for the presence of OP and/or spondylosis. Unfortunately, the precise duration between the radiographs and the questionnaire were unknown. However, women underwent lateral radiographs within a few years before the questionnaire. The subjects completed a structured questionnaire aimed at collecting information regarding self-reported kyphosis, self-reported height at a younger age, history of current and previous smoking, and history of diabetes mellitus, steroid use, rheumatoid arthritis, and use of OP medications. Self-reported kyphosis was simply defined using three categories: none, mild to moderate, and severe. Height loss was calculated according to current height and self-reported height at a younger age and was divided into two categories according to a previous study16: <4 cm or ≥4 cm.

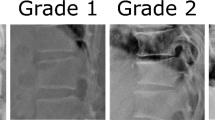

Two experienced orthopaedic surgeons, blinded to the responses in the questionnaires, independently determined the presence of vertebral fractures on lateral spinal radiographs using a semi-quantitative (SQ) method developed by Genant et al.10. With this SQ method, thoracic and lumbar vertebrae are graded by visual inspection of lateral spinal images, generally without direct vertebral measurements. The grades were as follows: SQ0, normal; SQ1, mildly deformed (approximately 20–25% reduction in anterior, middle, and/or posterior height and 10–20% reduction of the projected vertebral area); SQ2, moderately deformed (approximately 25–40% reduction in anterior, middle, and/or posterior height and 20–40% reduction of the projected vertebral area); SQ3, severely deformed (approximately ≥40% reduction in anterior, middle, and/or posterior height and in the projected vertebral area). Uemura et al. reported that assessment of vertebral fractures using the SQ method tended to be overestimated by inexperienced physicians compared with those done by experts. For example, the assessments evaluated in that study showed poor non-expert interobserver reliability but well-matched expert interobserver reliability19. Because experienced orthopaedic surgeons are experts in assessing vertebral fractures, it is likely that the surgeons in the present study diagnosed the vertebral fractures accurately.

We then counted the number of SQ1 and ≥SQ2 fractures. If the results were different between two observers, consensus was reached by discussion. The Ethics Committee of Matsumoto Dental University reviewed and approved the study protocol. The methods were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines, including any relevant details. Written informed consent was obtained from participants.

Data analysis

The data for continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). Multiple regression analysis in a stepwise manner—adjusted for age, height, weight, height loss category, and history of smoking (yes or no), diabetes mellitus (yes or no), steroid use (yes or no), rheumatoid arthritis (yes or no), and use of OP medications (yes or no)—was used to clarify the association between self-reported kyphosis and the number of SQ1 and ≥SQ2 vertebral fractures. Dummy variables were used for categorical data in this multiple regression analysis.

Logistic regression analysis with the stepwise forward selection method—adjusted for age, height, weight, height loss, history of smoking (binary), diabetes mellitus (binary), steroid use (binary), rheumatoid arthritis (binary), and use of OP medications (binary)—was used to calculate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the presence of fractures (SQ1, ≥SQ2, all fractures) according to the self-reported kyphosis category. Stepwise forward selection used in this study is the method with entry testing based on the significance of the score statistic (p ≤ 0.05), and removal testing based on the probability of the Wald statistic (p ≥ 0.10). The data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 19.0; IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, USA). Values of p < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Among the 691 patients aged ≥60 years who visited our orthopaedic clinic during June through August 2014, 127 men were excluded from this study. A total of 564 female patients were invited to complete a structured questionnaire examination. Among them, only one woman refused to answer questions on the questionnaire. Although 563 women answered a structured questionnaire examination and provided written informed consent, the answers from 40 of the women were insufficient for the analysis. Many missing or unclear data of the questionnaire were observed in these 40 women. Among the remaining 523 women, 407 aged 60–92 years who underwent lateral spine radiography before completing the structured questionnaire comprised the final participants in this study (Fig. 1). The time interval between the most recent lateral radiograph and the structured questionnaire examination varied among the subjects.

The characteristics of the study subjects are shown in Table 1. In all, 151 subjects reported no kyphosis, 207 had mild to moderate kyphosis, and 49 had severe kyphosis. One-hundred and forty-four (35.4%) subjects had SQ1 fractures. Of these, 78 subjects had 1 fracture, 48 had 2, 12 had 3, 5 had 4, and one had 5 fractures. One-hundred and twenty-seven (31.2%) subjects had ≥SQ2 fractures. Of these, 73 had 1 fracture, 27 had 2, 13 had 3, 8 had 4, 4 had 5, one had 6, and one had 7 fractures. Overall, 217 subjects (53.3%) had fractures ≥SQ1 grade. Almost all of the subjects (89.9%) were taking some OP medication(s) at the time of answering the questionnaire. The mean self-reported height loss was 3.4 cm for the study subjects, and 139 (34.2%) subjects had height loss of ≥4 cm. Table 2 shows the association between self-reported kyphosis, self-reported height loss, and fracture status.

Multiple regression analysis revealed that the self-reported no kyphosis was significantly associated with a decreased number of both SQ1 (p < 0.001) and ≥SQ2 (p = 0.007) fractures (Table 3). Self-reported severe kyphosis was significantly associated with an increased number of ≥SQ2 fractures (p = 0.025). Aging was significantly associated with an increased number of SQ1 fractures (p = 0.010). Increase of self-reported height loss was significantly associated with an increased number of ≥SQ2 fractures (p < 0.001). Use of OP medication (p = 0.001), greater height (p = 0.009), and steroid use (p = 0.025) were significantly associated with fewer ≥SQ2 fractures. R2 was much smaller for SQ1 fractures than for ≥SQ2 fractures.

Logistic regression analysis with stepwise forward selection after adjusting for the covariates indicated that the ORs for having vertebral SQ1 fractures associated with self-reported mild-to-moderate and severe kyphosis were 2.8 (95% CI, 1.7 to 4.4) and 3.6 (95% CI, 1.8 to 7.1), respectively (Table 4). The ORs for having vertebral ≥SQ2 fractures associated with mild-to-moderate and severe self-reported kyphosis were 1.8 (95% CI, 1.0 to 3.1) and 3.5 (95% CI, 1.6 to 7.7), respectively. The ORs for having any vertebral fractures associated with mild-to-moderate and severe self-reported kyphosis were 2.1 (95% CI, 1.4 to 3.3) and 4.2 (95% CI, 1.8 to 9.5), respectively. Additionally, the ORs for having vertebral ≥SQ1 fractures or any-grade fractures associated with self-reported height loss (≥4 cm) were 3.2 (95% CI, 1.9 to 5.3) and 2.3 (95% CI, 1.4 to 3.7), respectively. Use of OP medications contributed to a significantly decreased risk of having vertebral ≥SQ2 fractures.

Discussion

This study showed that simple self-reported kyphosis and height loss were significantly associated with the presence and number of vertebral fractures in elderly Japanese women. This finding suggests that these self-reported indices, especially simple self-reporting of kyphosis, are useful for identifying Japanese women aged ≥60 years who have undetected vertebral fractures.

There have been numerous reports on physical findings and risk factors for OP, including low weight, low height, spinal fracture, and skeletal BMD, especially in postmenopausal women20,21,22. Several thresholds for height loss have been suggested to identify individuals who have asymptomatic (morphometric) vertebral fractures. Some reports indicated that a 2- to 4-cm height loss is a clinical sign of spinal fracture13,15. We observed a significant association between self-reported height loss ≥4 cm and increased risk of vertebral fractures determined by lateral radiography. There was also a significant relation between the progression of even mild self-reported kyphosis and radiographically detected fractures in our study. It is likely that many elderly people do not accurately remember their height at younger ages. One study of 8610 patients (mean age 70.9 years) noted that the patients’ estimated current height tended to be incorrect, with a mean difference of −2.5 cm from the current measured height15. Thus, memory difficulties might have caused the differences of the previous and present research. Also, as a methodology for evaluating OP based on posture, Green et al. reported that a wall–occiput distance of >0 cm and a rib–pelvis distance of less than two fingerbreadths suggest the presence of occult spinal fracture23. These authors also reported that height loss may be a useful surrogate marker for screening patients with undetected vertebral fractures. These methodologies are easily tested, although each method requires actual measurements of height or distance. In this study, our method required only simple self-reporting of the degree of kyphosis.

It is well known that vertebral fractures likely cause kyphosis. However, generally, it is not rare that vertebrae at the thoracolumbar junction are wedge-shaped, indicating that a patient with wedged-shape vertebrae might feel mild kyphosis. Thus, recognition of kyphosis does not necessarily imply the existence of a fracture. It is therefore challenging to evaluate subjectively whether a patient who feels mild kyphosis is experiencing vertebral fracture—even when using radiographs.

To date, there has been no method for evaluating kyphosis simply; as such, it is difficult to evaluate its severity. The present study showed that there is a significant risk of vertebral fracture even in patients with mild kyphosis. Thus, recognition of kyphosis and recognition of kyphosis severity are different entities. It has been speculated that severity of self-reported kyphosis is associated with the presence of vertebral fractures. Self-evaluation of kyphosis severity may thus be a helpful methodology with which to evaluate the possibility of vertebral fractures being present. Such inquiries would be important with respect to the medical examination and screening of patients at high risk of OP. The results of our current study indicated that self-reported kyphosis could be a useful surrogate marker of vertebral fracture in women aged ≥60 years.

The study showed that there were significant associations between age, current height, and number of fractures. These findings are reasonable because (1) the older the patients are, the more frequent are the fractures they have sustained; and (2) the fewer fractures the patients have, the taller they remain. Other factors contributed less to our findings. Steroid usage, for example, had a negative effect on developing a severe fracture. In fact, not all of the patients on a steroid or who had taken bisphosphonates had a severe fracture. Additionally, the patients given OP medication had less-severe fractures, probably because bisphosphonate treatment is less likely to be associated with severe fractures.

The most serious limitation of this study is that the plain radiographs were not obtained at the exact time of administering the questionnaire. However, before the questionnaires were applied, plain radiographs had been obtained in which we expected an increased frequency of fractures. Thus, we propose that examination of the radiographs and questionnaires be performed at the exact same time, which could increase the validity of the results in this study. Additionally, because we evaluated height loss at the time the questionnaire was administered, the comparisons of height loss and kyphosis would not be changed. Since the subjects knew whether they had a vertebral fracture or not, this could influence on the results of self-reported kyphosis and height loss. Nonetheless, the number of SQ1 fractures was only associated with self-reported kyphosis but not with self-reported height loss.

Second limitation is recall bias, which contributes to inaccuracies in body height at a younger age. When screening patients with undetected OP or vertebral fractures, however, it is impossible to know exactly the body height at younger age. A third limitation is the generalizability of our findings. Our study population consisted of patients who visited an orthopaedic clinic; therefore, our results cannot be applied to the population of Japanese women aged ≥60 years in general. In addition, about 90% of the subjects were already taking OP medications when the study began. However, new vertebral fractures were not observed after that treatment had started. This resource-limited environment might have influenced the findings of our study.

The final limitation is exclusion criteria. The prevalence of patients 40 years and older with OP was 3.4% in men and 19.2% in women in Japan24. On the other hand, the prevalence of patients with lumbar spondylosis was larger in men than in women. Although not including men is a weakness of our study, men were excluded because of potential influences by lumbar spondylosis and spinal degeneration.

The strength of our current study is a significant association between the number and presence of SQ1 fractures and self-reported kyphosis. The SQ1 fracture is considered a slight fracture. It is not diagnosed as a fracture when we apply a semi-quantitative diagnostic method in our institution. In this study, we do not inform an OP patient that there is a vertebral SQ1 fracture, so the patients do not know that it is present. Nonetheless, in this study, we found a significant association between the presence and number of SQ-detected fractures and self-reported kyphosis. This result implies that self-reported kyphosis may be a useful screening tool for identifying women aged ≥60 years who have undetected, asymptomatic vertebral fractures.

Conclusion

To date, there has been no definitive study regarding the association between self-reported kyphosis, self-reported height loss, and the presence and number of undetected vertebral fractures in women aged ≥60 years. The results of this study showed that both self-reported kyphosis and height loss were significantly associated with the presence and number of vertebral fractures in Japanese women aged ≥60 years. These findings imply that these self-reported indices, especially simple self-reporting of kyphosis, may be useful tools for identifying elderly Japanese women who have undetected vertebral fractures.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Kamimura, M. et al. Associations of self-reported height loss and kyphosis with vertebral fractures in Japanese women 60 years and older: a cross-sectional survey. Sci. Rep. 6, 29199; doi: 10.1038/srep29199 (2016).

References

N. I. H. Consensus Development Panel. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA 285, 785–795 (2001).

Reginster, J. Y. & Burlet, N. Osteoporosis: a still increasing prevalence. Bone 38, S4–S9 (2006).

Hosoi, T. [On 2015 Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis: Diagnostic criteria of primary osteoporosis and the criteria for pharmacological treatment.] Clin Calcium 25, 1279–1283 (2015) (in Japanese).

Bow, C. H. et al. Ethnic difference of clinical vertebral fracture risk. Osteoporos Int 23, 879–885 (2012).

Kwok, A. W. et al. Prevalence of vertebral fracture in Asian men and women: comparison between Hong Kong, Thailand, Indonesia and Japan. Public Health 126, 523–531 (2012).

Ikeda, Y., Sudo, A., Yamada, T. & Uchida, A. Mortality after vertebral fractures in a Japanese population. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 18, 148–152 (2010).

Ross, P. D. Clinical consequences of vertebral fractures. Am J Med 10, 30S–42S (1997).

Vogt, T. M. et al. Vertebral fracture prevalence among women screened for the Fracture Intervention Trial and a simple clinical tool to screen for undiagnosed vertebral fractures: Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Mayo Clin Proc 75, 888–896 (2000).

Kendler, D. L. et al. Vertebral Fractures: Clinical Importance and Management. Am J Med 129, 221.e1-221.e10 (2016).

Genant, H. K., Wu, C. Y., van Kuijk, C. & Nevitt, M. C. Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J Bone Miner Res 8, 1137–1148 (1993).

Xu, W. et al. Height loss, vertebral fractures, and the misclassification of osteoporosis. Bone 48, 307–311 (2011).

Kado, D. M. et al. Factors associated with kyphosis progression in older women: 15 years’ experience in the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Bone Miner Res 28, 179–187 (2013).

Siminoski, K. et al. Accuracy of height loss during prospective monitoring for detection of incident vertebral fractures. Osteoporos Int 16, 403–410 (2005).

Yoshimura, N. et al. Association between height loss and bone loss, cumulative incidence of vertebral fractures and future quality of life: the Miyama study. Osteoporos Int 19, 21–28 (2008).

Briot, K., Legrand, E., Pouchain, D., Monnier, S. & Roux, C. Accuracy of patient-reported height loss and risk factors for height loss among postmenopausal women. CMAJ 182, 558–562 (2010).

Yoh, K., Kuwabara, A. & Tanaka, K. Detective value of historical height loss and current height/knee height ratio for prevalent vertebral fracture in Japanese postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Metab 32, 533–538 (2014).

Levin, R. M. Prevention of osteoporosis. Hosp Pract (Off Ed) 26, 77–80, 83–86, 91–94 (1991).

Ensrud, K. E., Black, D. M., Harris, F., Ettinger, B. & Cummings, S. R. Correlates of kyphosis in older women: The Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. J Am Geriatr Soc 45, 682–687 (1997).

Uemura, Y. et al. Comparison of expert and nonexpert physicians in the assessment of vertebral fractures using the semiquantitative method in Japan. J Bone Miner Metab 33, 642–650 (2015).

Schnatz, P. F., Marakovits, K. A. & O’Sullivan, D. M. Assessment of postmenopausal women and significant risk factors for osteoporosis. Obstet Gynecol Surv 65, 591–596 (2010).

Compston, J. E. et al. Relationship of weight, height, and body mass index with fracture risk at different sites in postmenopausal women: the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). J Bone Miner Res 29, 487–493 (2014).

Crandall, C. J. et al. Postmenopausal weight change and incidence of fracture: post hoc findings from Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study and Clinical Trials. BMJ 27, 350:h25 (2015).

Green, A. D., Colón-Emeric, C. S., Bastian, L., Drake, M. T. & Lyles, K. W. Does this woman have osteoporosis? JAMA 292, 2890–2900 (2004).

Yoshimura, N. et al. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis, lumbar spondylosis, and osteoporosis in Japanese men and women: the research on osteoarthritis/osteoporosis against disability study. J Bone Miner Metab 27, 620–8 (2009)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Nos 24592849, 26463148, and 90119222).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Kamimura and A.T. contributed to the drafting of the manuscript, and analysis and interpretation of data. N.S., M.Komatsu, S.I. and S.U. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and revised it critically for important intellectual content. Y.N. and H.K contributed to the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and revised it critically for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kamimura, M., Nakamura, Y., Sugino, N. et al. Associations of self-reported height loss and kyphosis with vertebral fractures in Japanese women 60 years and older: a cross-sectional survey. Sci Rep 6, 29199 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29199

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29199

This article is cited by

-

Loss of height predicts fall risk in elderly Japanese: a prospective cohort study

Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism (2023)

-

Height loss in postmenopausal women—do we need more for fracture risk assessment? Results from the GO Study

Osteoporosis International (2021)

-

Adult spinal deformity and its relationship with height loss: a 34-year longitudinal cohort study

BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders (2020)

-

Height loss but not body composition is related to low back pain in community-dwelling elderlies: Shimane CoHRE study

BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders (2019)

-

Long waiting time before tooth extraction may increase delayed wound healing in elderly Japanese

Osteoporosis International (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.